The Mohmand Field Force, between 7th August and 1st October 1897; the British operation against the Hadda Mulla and the Mohmand tribe, in the face of the spreading uprising along the North-West Frontier of India in 1897

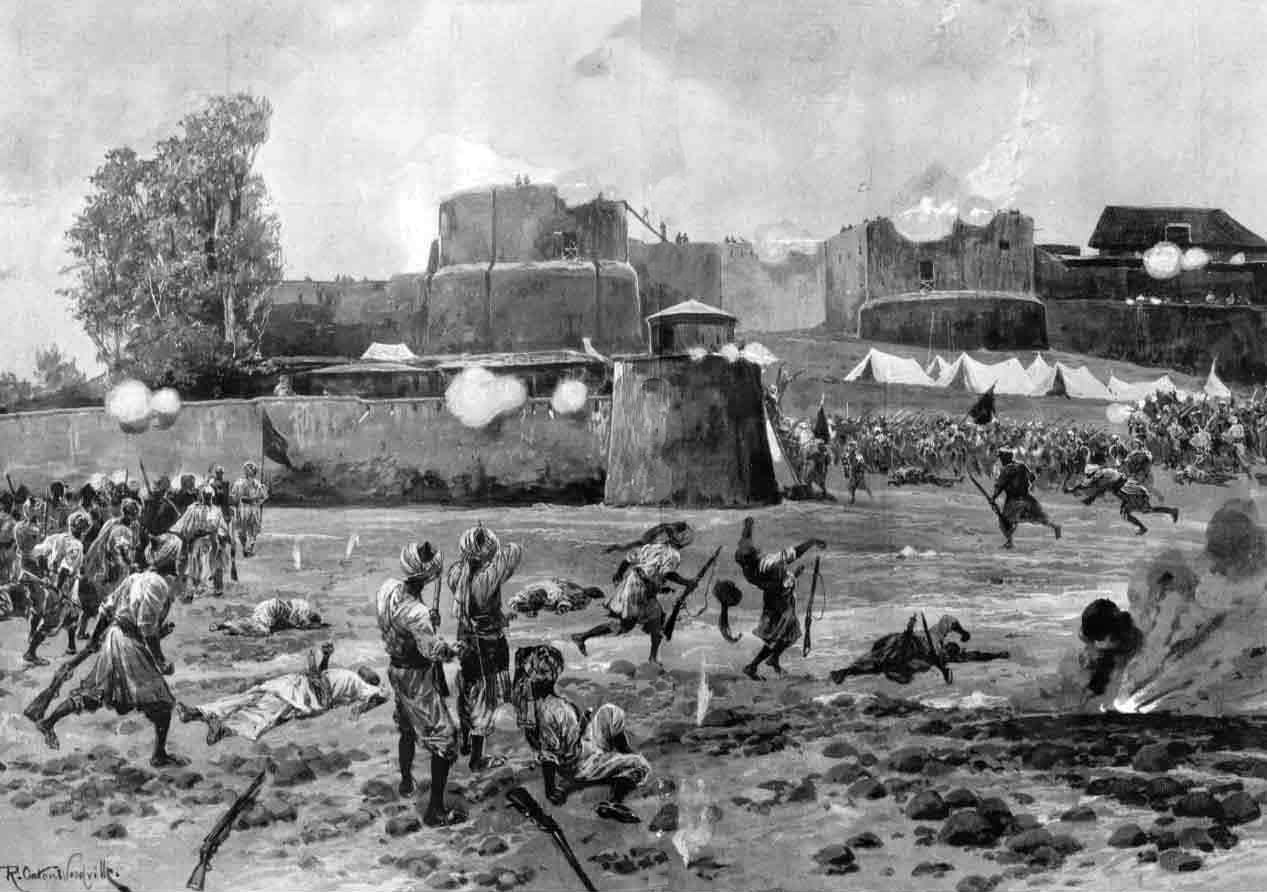

Attack on Shabkadar Fort on 7th August 1897: Mohmand Field Force, 7th August to 1st October 1897, North-West Frontier of India: picture by Richard Caton Woodville

The previous battle in the North-West Frontier of India sequence is the Malakand Field Force 1897

The next battle in the North-West Frontier of India sequence is Tirah 1897

To the North-West Frontier of India index

War: North-West Frontier of India:

Date of the Mohmand Field Force 1897: 7th August to 1st October 1897

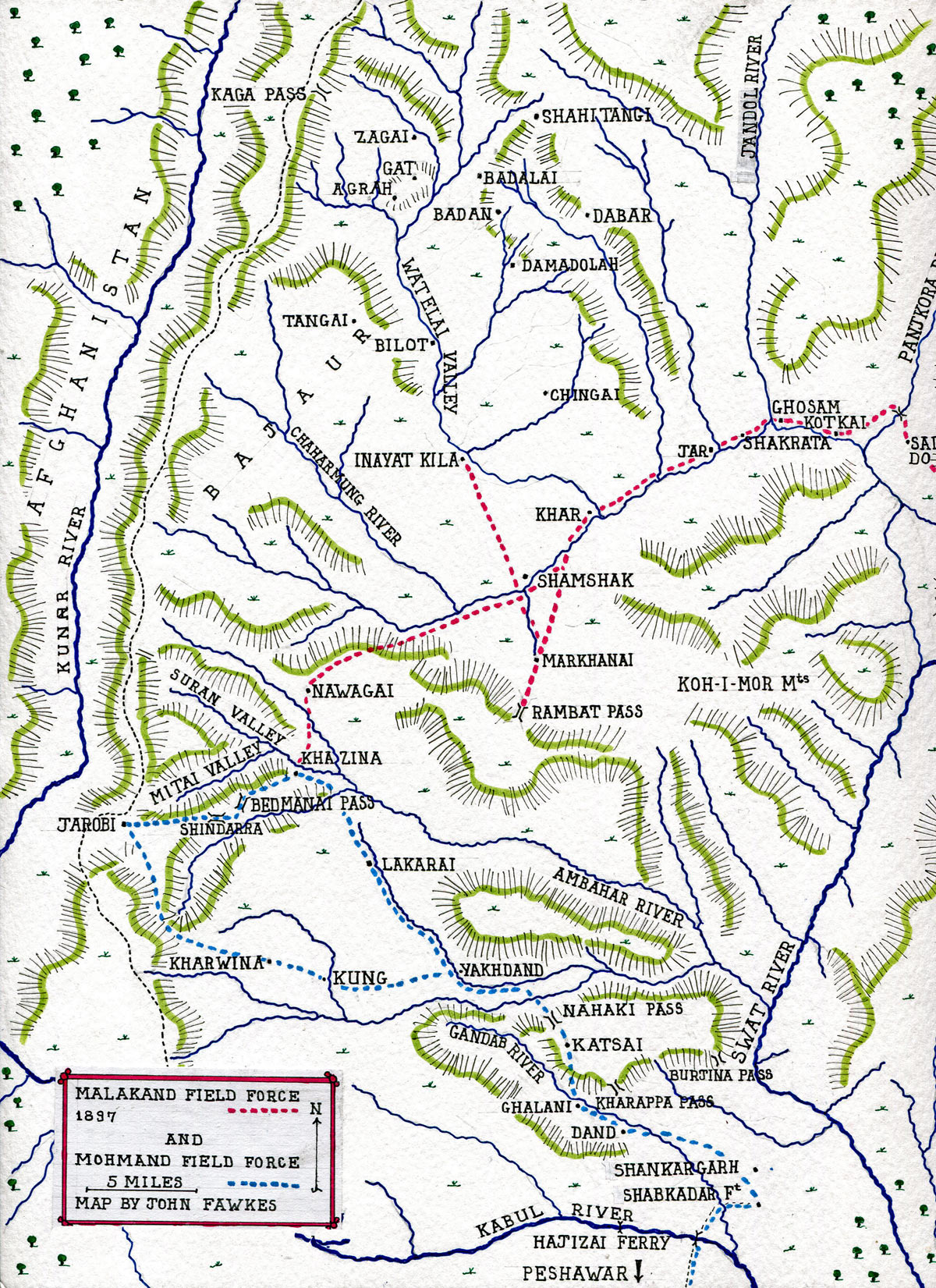

Place of the Mohmand Field Force 1897: the Mohmand tribal region to the north of the Kabul River and to the west of the Panjkora River.

Combatants in the Mohmand Field Force 1897: troops of the British and Indian armies against the clans of the Mohmand tribe.

Major General Edmond Elles, commander of the Mohmand Field Force: Mohmand Field Force, 7th August to 1st October 1897, North-West Frontier of India

Note: the Mohmands and Mamunds are different tribes. The Mohmands occupy the area along the north bank of the Kabul River. The Mamunds are their immediate neighbours to the north. See the Malakand Field Force 1897 for the simultaneous operation against the Mamunds by General Sir Bindon Blood.

Commanders in the Mohmand Field Force 1897: Major-General Elles commanded the Mohmand Field Force. The tribes were inspired and on occasions led by the Hadda Mulla, a Muslim cleric based in the western Mohmand village of Jarobi.

Size of the forces in the Mohmand Field Force 1897: the Mohmand Field Force varied around a size of 1,500 men. The numbers of tribesmen varied widely according to the stage of the operation and are given in the text.

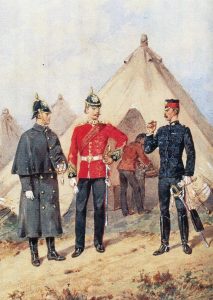

Uniforms, arms and equipment in the Mohmand Field Force 1897:

The British military forces in India fell into these categories:

- Regiments of the British Army in garrison in India. Following the Indian Mutiny of 1857, India became a Crown Colony. The ratio of British to Indian troops was increased from 1:10 to 1:3 by stationing more British regiments in India. Brigade formations were a mixture of British and Indian regiments. The artillery was under the control of the Royal Artillery, other than some Indian Army mountain gun batteries.

- The Indian Army comprised the three armies of the Presidencies of Bombay, Madras and Bengal. The Bengal Army, the largest, supplied many of the units for service on the North-West Frontier. The senior regimental officers were British. Soldiers were recruited from across the Indian sub-continent, with regiments recruiting particular nationalities, such as Sikhs, Punjabi Muslims, Pathans and Gurkhas. The Indian Mutiny caused the British authorities to view the populations of the east and south of India as unreliable for military service.

- The Punjab Frontier Force: Known as ‘Piffers’. These were the regiments formed specifically for service on the North-West Frontier and were controlled by the Punjab State Government.

- Imperial Service Troops of the various Indian states, nominally independent but under the protection and de facto control of the Government of India. The most important of these states for operations on the North-West Frontier was Kashmir.

A British infantry battalion comprised ten companies, with around 700 men and some 30 officers. A battalion possessed a maxim machine gun detachment of two guns and some 20 men.

Indian infantry battalions had much the same establishment, but without the maxim gun detachment. Senior officers were British, holding Queen’s Commissions. Junior officers were Indian.

By the late 1890s, British regiments were issued with the magazine Lee-Metford rifle. The Indian Army regiments carried the single shot Martini-Henry. Both rifles took a bayonet.

As initially the Lee-Metford was seen as having inadequate stopping power in its use against fanatical tribesmen, the ammunition was modified to cause it to spread on impact, causing horrific wounds. These rounds were manufactured at the Government of India Arsenal at Dum-Dum. The rounds were called ‘dum-dums’ and outlawed by the Geneva Convention. The Lee-Metford was finally replaced by the Lee-Enfield rifle, which fired a larger .303 round and continued in service with the British army through both world wars and beyond.

2.5 inch RML Mountain Gun, ‘Screw Gun’: Mohmand Field Force, 7th August to 1st October 1897, North-West Frontier of India: Firepower Museum

The British and Indian Mountain Batteries used the 2.5-inch RML muzzle loading rifled gun, carried by mules. The barrel was broken into two sections for carrying, giving the gun its characteristic nickname of the ‘screw-gun’.

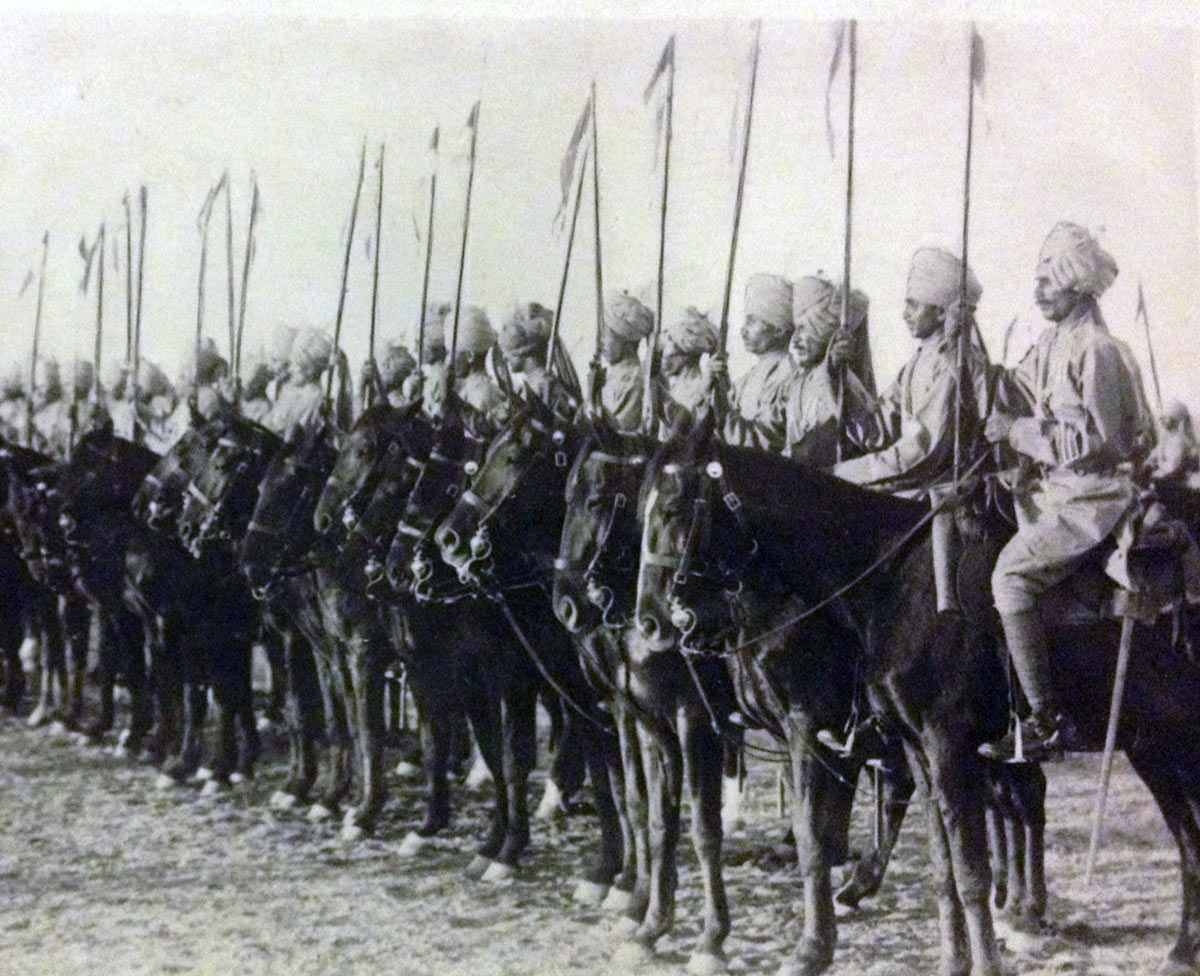

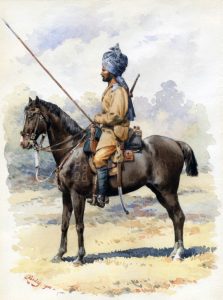

The cavalry regiments were armed with lances, swords and carbines.

13th Bombay Lancers: Mohmand Field Force, 7th August to 1st October 1897, North-West Frontier of India

Regiments in the Mohmand Field Force 1897:

11th Bengal Lancers

13th Bengal Lancers

1st Somerset Light Infantry

1st Queen’s Regiment (West Surreys)

2nd Oxfordshire Light Infantry

2nd/1st Gurkhas

9th Gurkha Rifles

20th Punjab Infantry

22nd Punjab Infantry

28th Bombay Pioneers

39th Garwhal Rifles

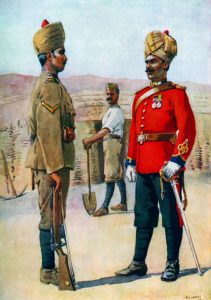

No. 5 Company Bengal Sappers and Miners

No. 3 Company Bombay Sappers and Miners

No. 1 Mountain Battery, Royal Artillery

No. 3 Mountain Battery, Royal Artillery

No. 5 (Bombay) Mountain Battery

Patiala Regiment

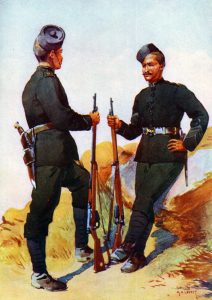

39th Garwhal Rifles: Mohmand Field Force, 7th August to 1st October 1897, North-West Frontier of India: picture by AC Lovett

Winner of the Mohmand Field Force 1897: The British and Indian force.

Background to the Mohmand Field Force 1897: In 1897 the Muslim tribes rose against the British along the North-West Frontier of India. Expressions are used such as ‘the Frontier Ablaze’ to describe a phenomenon that took the British Government of India almost completely by surprise.

The uprising began with the attack on the Malakand camp, to the north of the Kabul River, on 26th July 1897. Risings followed in Mohmand country further west and to the south of the Kabul River in the Tirah.

The British Government of India was compelled to mobilise substantial military forces to combat the tribes and the military operations became the centre of interest in Britain.

Winston Churchill wrote his first book of importance, after his involvement in the ‘the story of the Malakand Field Force’ in 1897.

The reasons for the tribal uprisings in 1897:

There is little doubt that the basic reason for the tribes’ antipathy towards the British was the clear intention of the British to incorporate much of the tribal lands into British India.

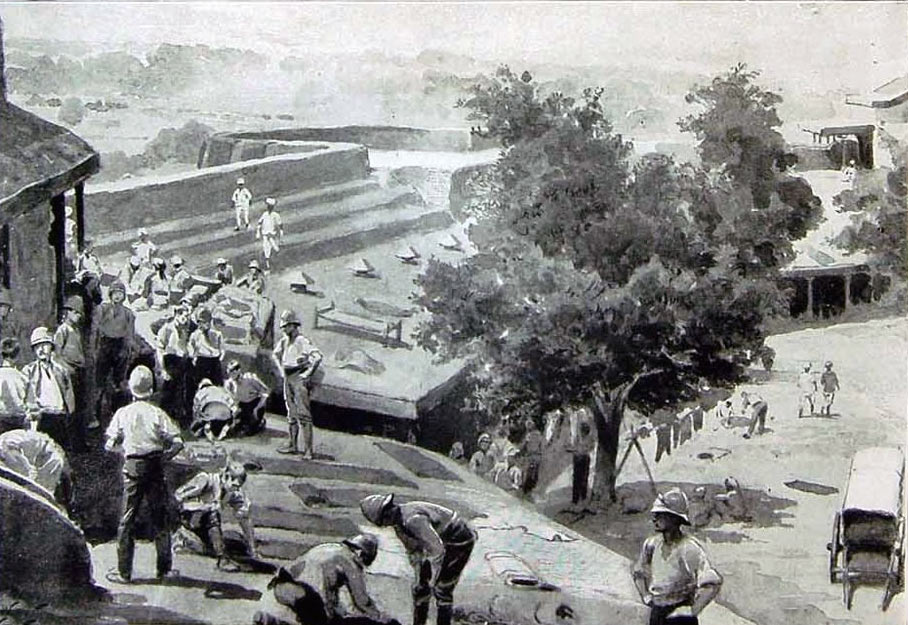

Soldiers of the 28th Bombay Pioneers: Mohmand Field Force, 7th August to 1st October 1897, North-West Frontier of India

The close British connection with the North-West Frontier began with the annexation of the Punjab, following the two Sikh Wars. The border of the Punjab lay along the Indus. Tribal lands lay along the western and north-western banks of the Indus.

British obsession with the threat to India from Russia led to the formulation of the ‘Forward Policy’, which envisaged British influence, if not direct rule, up to the line of the Himalayan passes in the north and the Afghan border, wherever it lay, in the west.

Following the Second Afghan War, the British compelled the Amir of Afghanistan to agree to the establishment of a settled border between Afghanistan and British India. The work on demarking the border was carried out in the 1880s by the Durand Commission, which began to set up a row of white posts through the tribal lands, although the work had to be abandoned in the face of tribal opposition.

Most of the Muslim tribes along the North-West Frontier of India considered themselves to be nominal subjects of the Amir of Afghanistan. The idea of subjection to a non-Muslim state, British India, was anathema to all, other than some minor rulers who benefited financially from British rule.

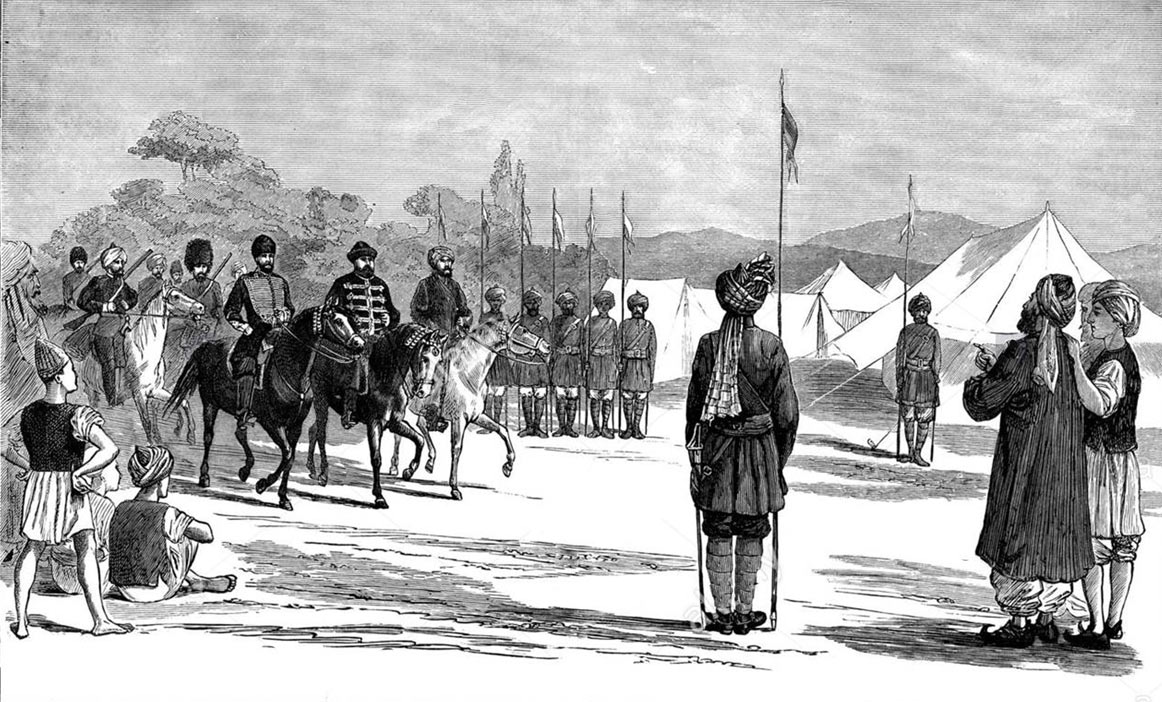

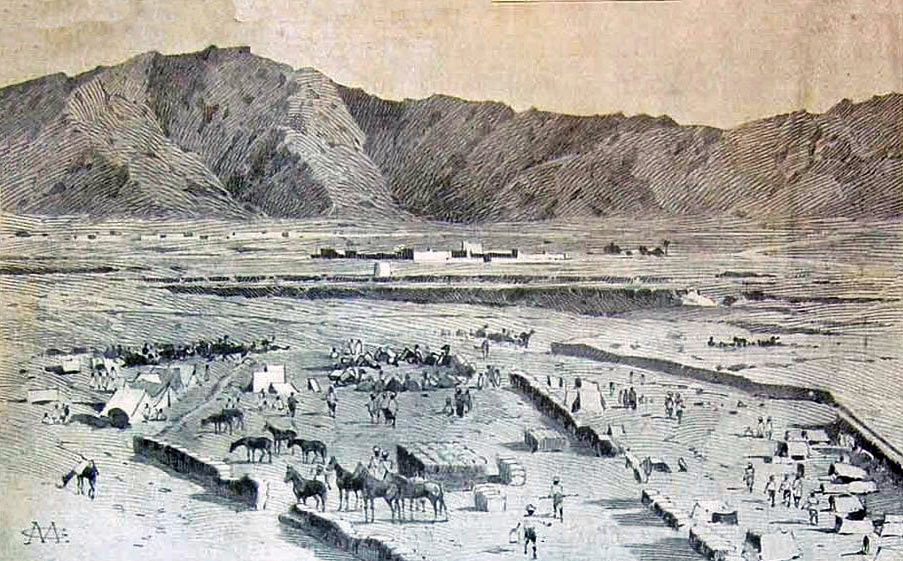

Mohmand Field Force in camp at Nahaki: Mohmand Field Force, 7th August to 1st October 1897, North-West Frontier of India: picture by Melton Prior

The Chitral campaign in 1895 was of particular significance. The dispute over the mehtarship of Chitral and the siege of British and Indian troops in Chitral Fort gave the British Government of India the excuse to move into Chitral and install a mehtar firmly under British control. An Indian garrison was established at Chitral town and a road built from the border cantonment of Malakand to Chitral. All the intervening minor rulers, the Khans of Dir and Jandol and others, received British subsidies to maintain and protect the road. The worst fears of the border tribes as to the ambitions of the British were fulfilled.

No 3 Mountain Battery, Royal Artillery: Mohmand Field Force, 7th August to 1st October 1897, North-West Frontier of India

In 1897, it is believed that the final trigger for the tribal uprising, orchestrated by Muslim clerics as a Jihad, was the defeat of the Christian Greeks by the Muslim Turks in the Balkans.

One of the Muslim clerics leading the attack on the Malakand was the Mahmond Hadda Mulla from Jarobi.

Once the British and Indian ‘Malakand Field Force’ relieved the Malakand garrison and Chakdara Fort and moved up the Swat River, the rising in the Lower Swat subsided and the Hadda Mulla moved back into Mahmond country, to the west of the Panjkora River, to continue the rising.

Map of the operations of the Malakand Field Force and the Mohmand Field Force in 1897: map by John Fawkes

Account of the Mohmand Field Force 1897:

On 7th August 1897, the Hadda Mulla, now leading a force from the Mohmand clans amounting to 4,000 to 5,000 tribesmen, crossed the Afghan border into British India and advanced to attack the largely Hindu village of Shankargarh, to the north of the Kabul River.

Half the mullah’s force sacked Shankargarh, while the other half attacked the nearby Shabkadar Fort, held by a garrison of 60 Border Military Police and Peshawar District Police, led by Subadar-Major Abdur Rauf Khan.

The attack was repelled with some 40 casualties inflicted on the tribesmen. Some of the mullah’s force withdrew into Afghanistan, while the remainder remained in the area of Shabkadar Fort.

News of the tribal advance reached Peshawar on the evening of 7th August 1897 and a British and Indian column marched out that night for Shabkadar Fort, comprising 2 squadrons of 13th Bengal Lancers, 4 field guns, 2 companies of the Somerset Light Infantry and the 20th Punjab Infantry, all commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Woon of the 20th.

Inside Shabkadar Fort: Mohmand Field Force, 7th August to 1st October 1897, North-West Frontier of India

The route from Peshawar to Shabkadar Fort was some fifteen miles, across the Kabul River, in spate at this time of year. The river was crossed at the Hajizai ferry, operated by a number of boats, insufficient to convey the military force with any speed.

Troops by the road side: Mohmand Field Force, 7th August to 1st October 1897, North-West Frontier of India

The first troops taken across the ferry were a squadron of the 11th Bengal Lancers, which hurried on to assist the Shabkadar garrison, although the attack had ended before the squadron reached the fort.

Woon arrived with part of his force on the 8th August 1897 and engaged the tribesmen, but was compelled to withdraw to the fort to await the arrival of the rest of his column.

With his full force, Woon renewed the attack on 9th August 1897, but was still in insufficient strength to make headway against the tribesmen.

13th Bengal Lancers charging the Hadda Mulla’s tribesmen at Shabkadar: Mohmand Field Force, 7th August to 1st October 1897, North-West Frontier of India: picture by Edmund Hobday

During the course of this engagement, the squadron of 11th Bengal Lancers carried out a charge from the right wing down the line of tribesmen dispersing them.

As Woon was withdrawing, General Elles arrived, re-deployed the small force and pushed the tribesmen back into the hills, while more troops marched in from Peshawar.

There was now an assessment of the crisis facing the British authorities. It was clear that there were some 5,000 to 6,000 tribesmen assembled in the hills. What was less easy to assess was from which tribes and clans the tribesmen were drawn.

Working out the makeup of the tribal force was essential for devising the counter-strategy to be adopted. This was initially to defeat the force, but then to destroy the villages and crops of the tribes and clans in insurrection. This second feature of the campaign, essential to ensure future peace, in the view of the British authorities, could only be carried out with reliable information as to which tribes and clans were involved. Destruction of the villages and crops of the wrong clans would be liable to drive them to join the hostile force.

With the assistance of the British political officers, General Elles worked out that the tribal force he faced comprised men from all the Mohmand tribes and clans living in the area to the west of the Panjkora River, to the north of the Kabul River, to the east of the Afghan frontier and to the south of the Koh-i-Mor Mountains. Other men came from the Swat Valley, from across the Afghan border and from the areas further north. The tribes included the Mohmands, the Utman Khels, the Safis, Mians, Shinwaris, Khugianis and Utkel Ghilzais.

The British and Indian force at Shabkadar was increased to 2,500 men, the Hajizai Ferry being replaced by a bridge of boats and a field telegraph line being installed from Peshawar to Shabkadar.

More troops were brought up to Peshawar to form a second column.

Prince Albert’s Somerset Light Infantry on exercise in England: Mohmand Field Force, 7th August to 1st October 1897, North-West Frontier of India: picture by Orlando Norie

In view of the failure of his surprise raid against Shabkadar, the Hadda Mulla left his army, reportedly going to Jarobi on the Afghan border and various tribal groups began to negotiate with the British political officers, the justification for their hostile actions being the influence of the Hadda Mulla over the tribesmen.

By the end of August 1897, the Hadda Mulla was again raising a force and was in communication with the Afridis in the Khaibur and the cleric in Swat labelled by the British as the ‘Mad Fakir’.

Encouraged by the Hadda Mulla, the ‘Mad Fakir’ planned to attack the Khan of Dir, an ally of the British.

This second move by the Hadda Mulla caused the British authorities to bring forward their operation against the Mohmands, despite the heavy commitment in the Tirah against the Afridis.

Two forces would operate against the Mohmands. General Elles would march north from Shabkadar Fort and General Sir Bindon Blood, commanding the Malakand Field Force, would break off his operation up the Swat River, having reached Mingaora, cross the Panjkora River and invade Mohmand country from the east, with two of his three brigades.

This page covers the operations of Brigadier Elles with the Mohmand Field Force.

The Hadda Mulla was still in Jarobi. Mohmand clans assembled to hold the Kharappa and Burjina passes against Elles’s troops.

However, the Tarakzai clan, occupying an important area on both sides of the Kabul River to the west, undertook to keep the Hadda Mulla’s tribesmen out of their area and prevent them from crossing the Kabul River, thereby securing Elles’s left flank, as his troops advanced to the Kharappa and Burjina passes.

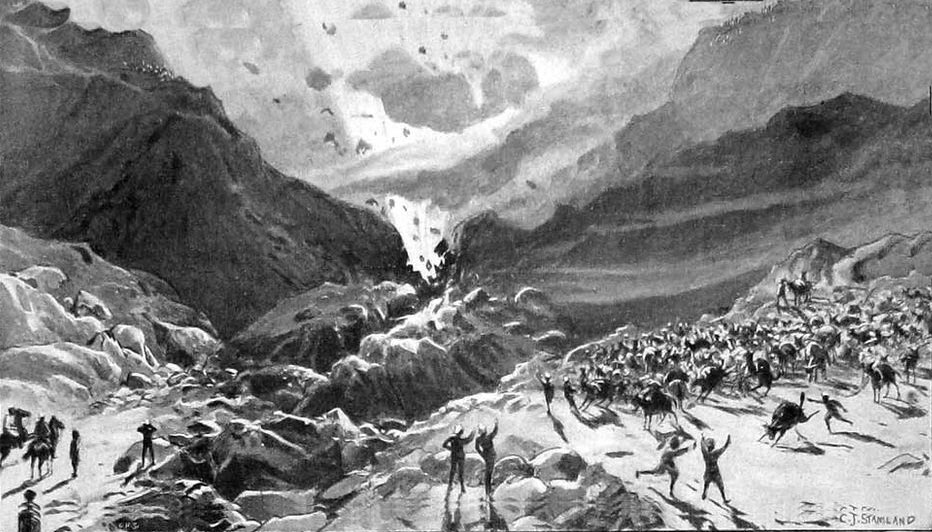

Sappers and Miners clearing a road in the Nahaki Pass: Mohmand Field Force, 7th August to 1st October 1897, North-West Frontier of India: picture by CJ Stamland

On 15th September 1897, the Mohmand Field Force began its advance north. The First Brigade, with General Elles and his headquarters, marched up the Kharappa Pass to Ghalani, eighteen miles in intense heat, while the Second Brigade followed to Dand.

Beyond Dand the route was impassable for camel convoys and a halt was called at Ghalani, to enable the path to be improved, as it was urgent to bring up supplies for Sir Bindon Blood’s brigade of the Malakand Field Force at Nawagai Camp. The route was described as like a staircase of blocks of rock, up which the animals had to be hauled.

Gurkhas in the Nahaki Pass: Mohmand Field Force, 7th August to 1st October 1897, North-West Frontier of India: picture by William Barnes Wollen

On 17th September 1897, troops of Elles’s First Brigade reached Katsai, 2 ½ miles south of the Nahaki Pass. Attempts to establish signal contact with the brigade in Nawagai Camp were unsuccessful, but a letter arrived from Sir Bindon Blood saying that the Hadda Mulla was in the Bedmanai Pass with 1,000 tribesmen, but that he could make no move from Nawagai, until his second brigade was available from its operations in the Mamund Valley.

By the 18th September 1897, the camel path and telegraph line to Ghalanai were complete.

The jirga of the Halimzai from Gandab came in to General Elles’s camp and negotiated an end to hostilities by that clan of the Mohmands.

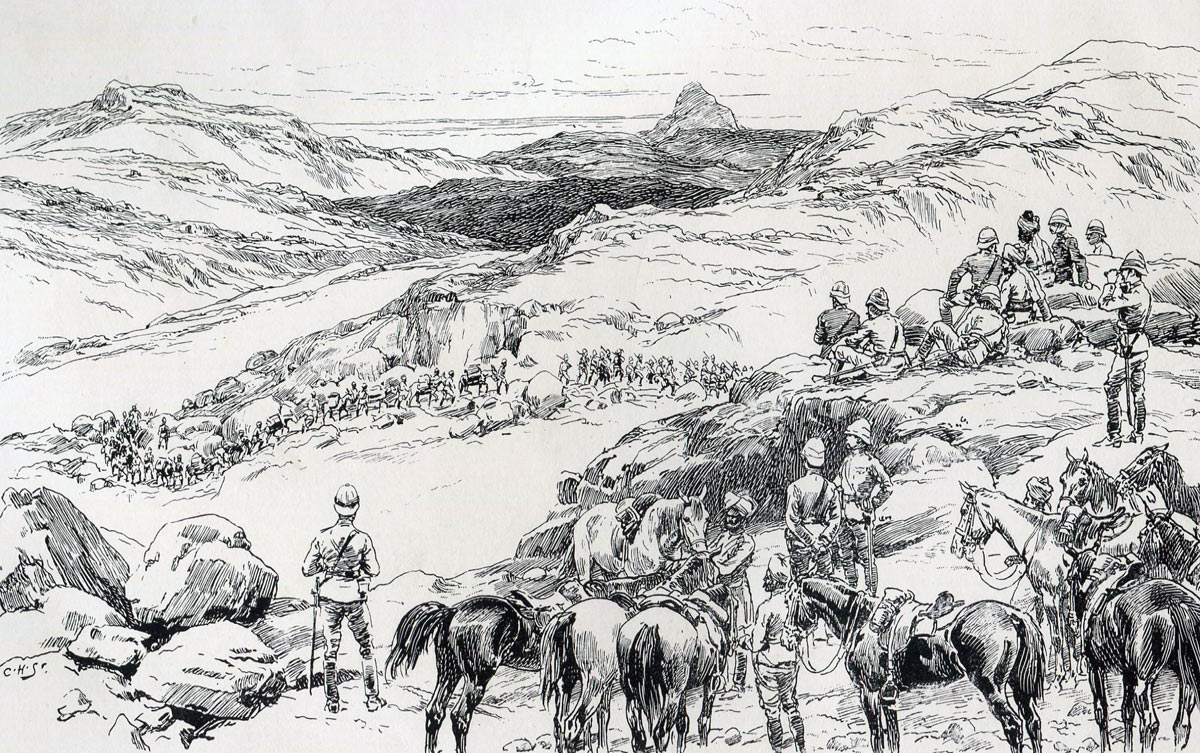

The Mohmand Field Force advances into the Bedmanai Valley on 22nd September 1897: Mohmand Field Force, 7th August to 1st October 1897, North-West Frontier of India

The Mohmand Field Force moved its forward units to Nowaki Village and other units moved up to Ghalanai.

Later, on 18th September 1897, General Elles received a request from Sir Bindon Blood for assistance in driving the Hadda Mulla’s tribesmen from the Bedmanai Pass.

On 21st September 1897, General Elles marched, with his First Brigade and the cavalry and artillery from the Mohmand Field Force, to Lakarai. A squadron of cavalry moved up to Khazina, but met no opposition.

General Blood met General Elles at Lakarai and informed him of the attacks on Nawargai Camp by the tribesmen on 19th and 20th September 1897 and that a hostile force was reported at Bedmanai of over 4,000 tribesmen.

General Blood ordered General Elles to clear the Bedmanai Valley and then the Mitai and Suran Valleys of hostile tribesmen. For this operation, Blood transferred his Third Brigade and mountain battery, then at Nawagai Camp, to Elles’s command and left to join Brigadier General Jeffrey’s Second Brigade in the Mamund Valley.

On 22nd September 1897, Elles’s force concentrated in Khazina, at the entrance to the Bedmanai Pass, where it was joined by the Third Brigade of the Malakand Field Force from Nawagai Camp.

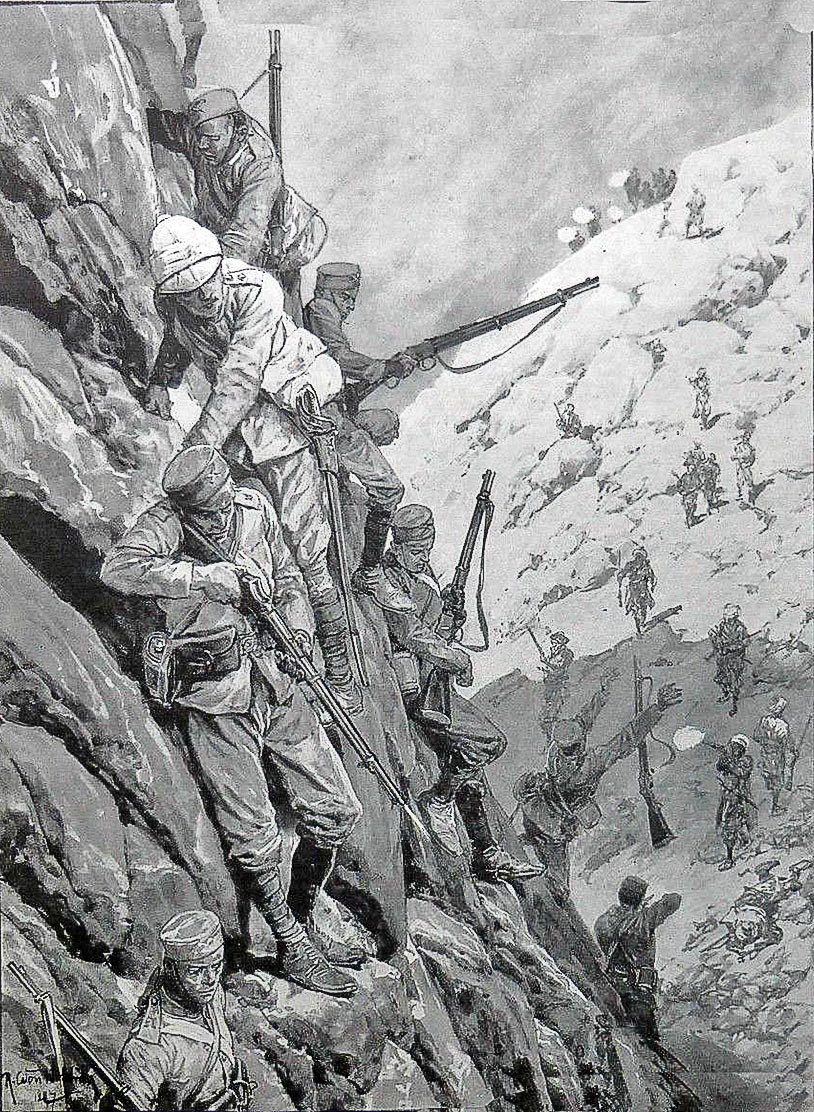

Gurkhas under fire while descending a cliff face: Mohmand Field Force, 7th August to 1st October 1897, North-West Frontier of India: picture by Richard Caton Woodville

The path up the Bedmanai Pass followed a dry nalla. The Third Brigade, Malakand Field Force, with one battery, advanced up this path, while the First Brigade, Mohmand Field Force, took a route along the high ground on the left, to outflank the tribesmen’s positions at the head of the valley.

The baggage, with an escort, remained in the camp near Khazina.

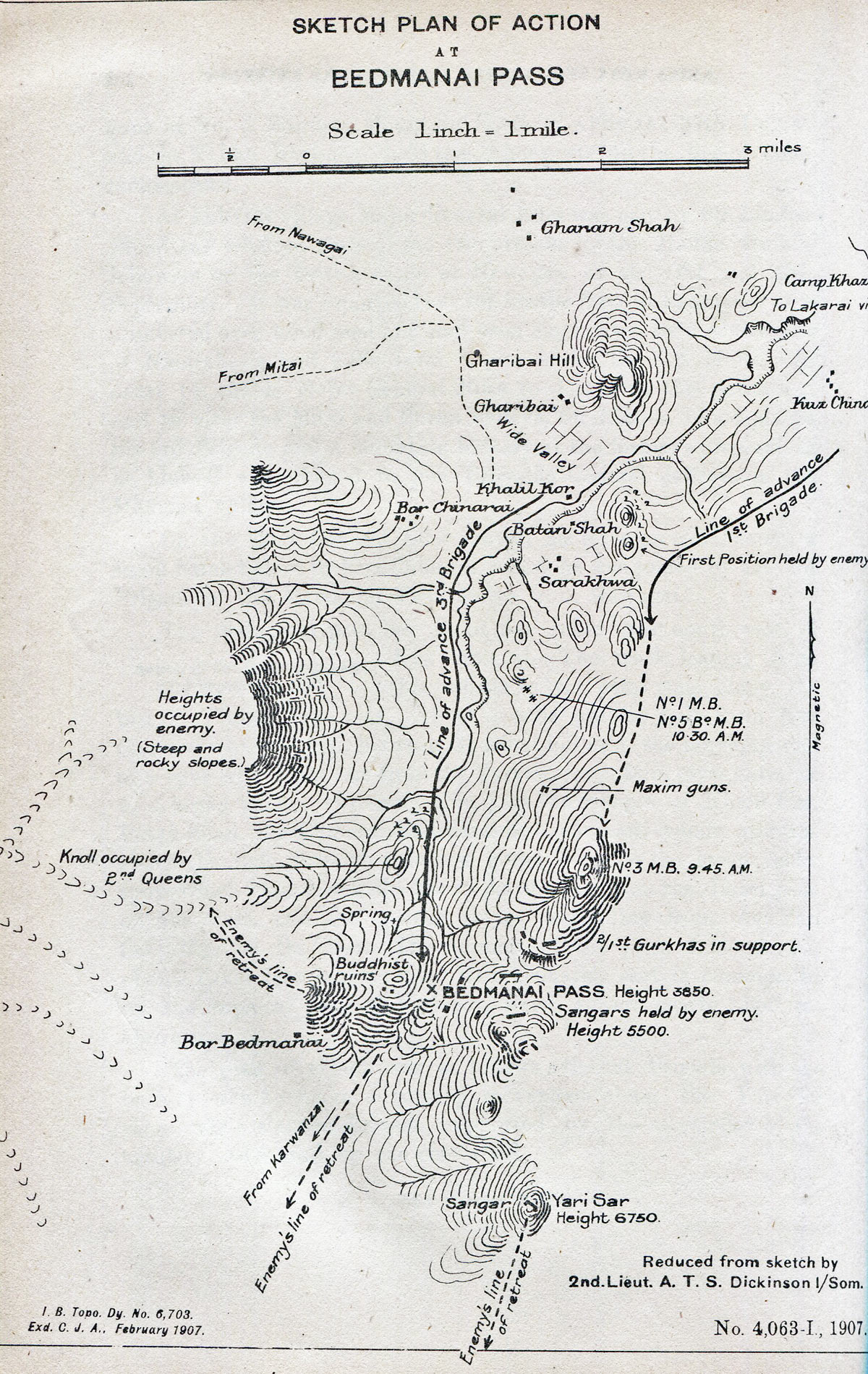

Sketch plan of the action in the Bedmanai Pass on 22nd September 1897: Mohmand Field Force, 7th August to 1st October 1897, North-West Frontier of India

As the force entered the valley, the 39th Garwhal Rifles took Gharibai Hill, overlooking the main path from the left, from a party of some 200 tribesmen.

4 squadrons of the 11th Bengal Lancers went off to the right to observe the tribesmen in the Mitai and Suran Passes. The tribesmen were in the Suran Pass in strength and opened a long-range rifle fire on the cavalry, who occupied the villages at the base of the pass and prevented the tribesmen from joining their fellows holding the Bedmanai Pass.

The Mohmand Field Force entering the Bedmanai Pass: Mohmand Field Force, 7th August to 1st October 1897, North-West Frontier of India: drawing by Edmund Hobday

Soon after 8am, the attack up the Bedmanai Pass began, with the 20th Punjab Infantry and the maxim gun detachment of the Somerset Light Infantry advancing past the Khalil Kor and driving back the tribesmen concealed in the rocks and trees. The 1st Gurkhas and 28th Bombay Pioneers followed in support, with No. 3 Mountain Battery.

The Third Brigade advance up the main path past Gharibai Hill was led by the Queen’s and the 22nd Punjab Infantry, supported by the brigade’s two mountain batteries.

The two brigades drove the tribesmen up the pass, until at around 10am, the 20th Punjab Infantry, supported by the fire of No. 3 Mountain Battery, stormed the sangars on the 5,500 foot crowning peak on the southern side of the pass.

Many of the tribesmen withdrew to the Yari Sar peak of 6,750 feet, where they occupied a large stone sangar.

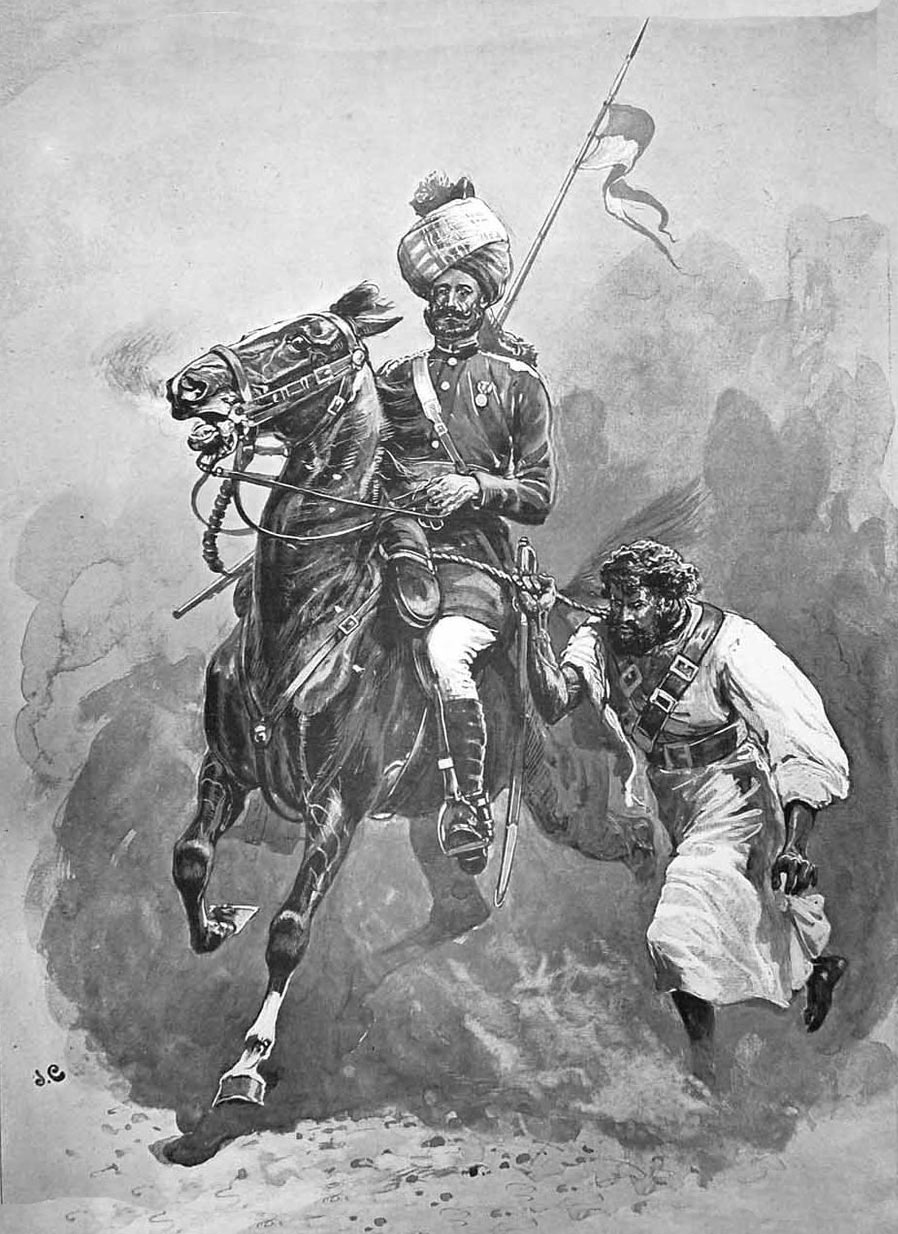

13th Bengal Lancer bringing in a Pathan prisoner: Mohmand Field Force, 7th August to 1st October 1897, North-West Frontier of India: picture by John Charlton

As these attacks went in, the two Third Brigade Mountain Batteries came into action, bombarding the tribesmen holding the Buddhist ruins on the western side of the head of the Bedmanai Pass. These tribesmen withdrew west, up the side of the mountain while the Queen’s occupied a knoll in the middle of the pass.

1st Gurkhas and No. 3 Mountain Battery moved forward onto the 5,500 foot spur, from where they provided covering fire, as the 20th Punjab Infantry advanced to take the Yari Sar sangar. The tribesmen streamed away to the south, under fire from the Somerset Light Infantry maxims, which had managed to keep up with the Punjabis.

No 3 Mountain Battery, Royal Artillery: Mohmand Field Force, 7th August to 1st October 1897, North-West Frontier of India

The Queen’s and the 22nd Punjab Infantry occupied the head of the Bedmanai Pass and, with the ending of tribal resistance, the Sappers and Miners began the arduous task of making the path up the pass usable for the transport animals.

British and Indian casualties amounted to 1 killed and 3 wounded. It turned out that there had only been around 700 or 800 tribesmen holding the pass, a substantial force of tribesmen being held in the Mitai and Suran passes by the small force of 13th Bengal Lancers. The retreating tribesmen took their dead and wounded with them, so that it was not possible to give an accurate assessment of their casualties, but they were considered to have been substantial.

Destruction of the Hadda Mulla’s mosque at Jarobi: Mohmand Field Force, 7th August to 1st October 1897, North-West Frontier of India: drawing by Edmund Hobday

With the capture of the pass, the First Brigade moved down into the Bedmanai valley and occupied villages there, while the Third Brigade returned to Kuz Chinari, where the force had camped the night before and, on 24th September 1897, began destroying Musa Khel villages in the Mitai valley.

On 25th September1897, the Third Brigade destroyed villages in the Suran valley.

With the winding down of operations against the Mohmands, the Third Brigade was ordered to march south to join the Tirah Expeditionary Force and left for Peshawar, on 26th September 1897.

The attack on Jarobi: Mohmand Field Force, 7th August to 1st October 1897, North-West Frontier of India

On 25th September 1897, the First Brigade began the final attack on Jarobi, the Hadda Mulla’s stronghold in wild mountainous country.

A cavalry squadron, comprising troops from the 13th Bengal Lancers and the Patiala and Jodhpur Lancers, reached the Shindarra ravine. Checked by the ground, the cavalry was forced to wait for the Somerset Light Infantry and No. 3 Mountain Battery to come up and take over the advance.

Preparations were now made for the attack on Jarobi. The Somersets, 28th Bombay Pioneers and the mountain battery took up positions at the mouth of the Shindarra Gorge. 4 companies of 1st Gurkhas occupied the heights to the west. 3 companies of 20th Punjab Infantry entered the Shindarra Gorge with the Sappers and Miners and the mountain battery, making their way up the gorge and turning right into the Jarobi glen.

More resistance was encountered, with rifle fire from sangars on the hillsides, as the troops entered Jarobi. A party of Ghazis emerged from the Hadda Mulla’s mosque and charged with swords, being repelled by rifle fire.

First Brigade withdrawing after the attack on Jarobi: Mohmand Field Force, 7th August to 1st October 1897, North-West Frontier of India

Considerable damage was inflicted on the village and the First Brigade then retired, followed up by the tribesmen. The brigade bivouacked at Tor Khel.

On 26th September 1897, the First Brigade marched out of Tor Khel in two columns, the main column commanded by Brigadier General Westamott, with the baggage, marching south-east to Kharwina.

The second, smaller, column, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Sage of 1st Gurkhas, took a different route to Kharwina. Both columns destroyed several villages and fortified houses.

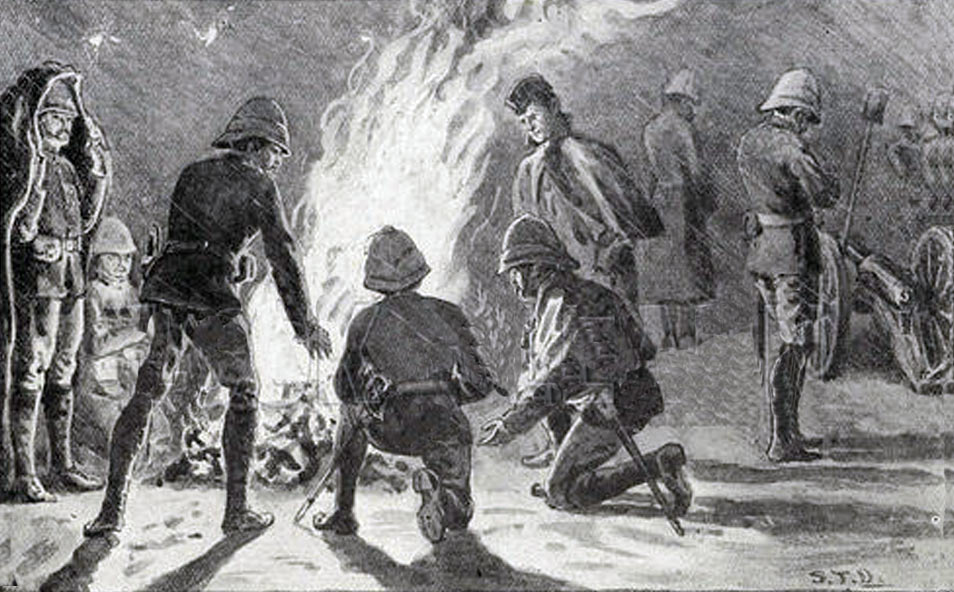

No. 3 Mountain Battery in bivouac: Mohmand Field Force, 7th August to 1st October 1897, North-West Frontier of India: picture by ST Dadd

Over the next few days, jirgas from several the tribes came into the British camp, now at Kung, seeking terms of peace. The brigade pushed on to Nahaki, suffering sniping at night, but it was clear that the hostilities were subsiding.

On 30th September 1897, the brigade marched on to Yakhdand and the peace arrangements continued to be negotiated.

Indian Medal 1895 with the clasp ‘Punjab Frontier 1897-8’: Mohmand Field Force, 7th August to 1st October 1897, North-West Frontier of India

The elements of the Mohmand tribe involved in the attack on Shankargarh had been punished. The Hadda Mulla’s followers had been dispersed. His base at Jarobi had been destroyed and he was considered by the British to have been discredited in the eyes of his followers.

British and Indian troops had crossed tribal country they had not before entered and destroyed numbers of villages and fortified houses of the offending tribes. The fines in money and weapons imposed had almost all been paid.

On 1st October 1897, the British authorities considered the operation to have been concluded with a satisfactory outcome and drew it to a close.

Battle Honours and campaign medal for the Mohmand Field Force 1897:

Participants in the Mohmand Field Force received the Indian Medal 1895 with the clasp ‘Punjab Frontier 1897-98’.

Participants in the Mohmand Field Force received the Indian Medal 1895 with the clasp ‘Punjab Frontier 1897-8’.

These regiments of the Indian army were awarded by the Vice-Roy of India the battle honour ‘Punjab Frontier’ arising from the Mohmand Field Force operations:

Sowar of 11th Bengal Lancers: Mohmand Field Force, 7th August to 1st October 1897, North-West Frontier of India

These regiments of the Indian army were awarded by the Vice-Roy of India the battle honour ‘Punjab Frontier’ arising from the Mohmand Field Force operations: 11th Bengal Lancers, 13th Bengal Lancers, Queen’s Own Guides, 1st PWO Sappers and Miners, 28th Bombay Pioneers, 39th Garwhal Rifles, 20th Punjab Infantry, 22nd Punjab Infantry, 1st Gurkhas and 9th Gurkhas. The British regiments did not receive the battle honour.

Casualties in the Mohmand Field Force 1897: casualties of each side are set out in the text above.

Anecdotes and traditions from the Mohmand Field Force 1897:

- The Hadda Mulla: Winston Churchill gives a short biography of the Hadda Mulla in ‘Malakand Field Force’. Churchill starts his account: ‘In the heart of the wild and dismal mountain region, in which these tribesmen dwell, are the temple and village of Jarobi: the one a consecrated hovel, the other a fortified slum. This obscure and undisturbed retreat was the residence of a priest of great age and of peculiar holiness, know to fame as the Hadda Mullah. His name is Najb-ud-din, but as respect has prevented it being mentioned by the tribesmen for nearly fifty years, it is only preserved in infidel memories and records.’ The title ‘Hadda Mulla’ refers to the cleric’s original home in Afghanistan, the village of Hadda, to the south of Jellalabad. In 1884 the Hadda Mulla raised the Mohmand tribe against the Amir of Afghanistan. He was summoned to appear in Kabul, but went to Jarobi, the Mohmand village outside the Amir’s jurisdiction. From Jarobi, the Hadda Mulla sent the Mohmands to resist the British incursion with the Chitral Relief Expedition in 1895. In 1896, the Hadda Mulla wrote a book, setting out his religious philosophy, in furtherance of a dispute with the pro-British ‘Manki Mullah of Nowshera’. This book, published in Delhi, was widely read by the Muslim community across the Indian sub-continent. The Hadda Mulla’s prestige was significantly enhanced. He became the friend and confidant of the Afghan commander-in-chief, Sipah Salar. In 1897, the Hadda Mulla sent the Mohmands to fight under the ‘Mad Fakir,’ in the attack on the Malakand Camp. The Hadda Mulla declared ‘Jihad’ against the British, before himself directing the attack on Shankargarh. The Hadda Mulla died in 1902, widely acclaimed, or blamed, for the 1897 Frontier Risings by the Tribes.

- As in all the border operations of the British on the North-West Frontier in 1897, an Afghan army, commanded by Sipah Salar, watched from the Afghan side of the border. Many Afghan soldiers joined the tribesmen in their battles with the British and Indian troops.

References for the Mohmand Field Force 1897:

Frontier and Overseas Expeditions from India Volume 1 published by the Government of India in 1905

North West Frontier by Captain H.L. Nevill DSO, RFA

The North-West Frontier by Michael Barthorp

The Frontier Ablaze, the North-West Frontier Rising 1897-1898 by Michael Barthorp

The previous battle in the North-West Frontier of India sequence is the Malakand Field Force 1897

The next battle in the North-West Frontier of India sequence is Tirah 1897

To the North-West Frontier of India index