The operations of the Malakand Field Force against the Mamund tribe from 8th September 1897 to 12th October 1897, on the North-West Frontier of India, described by Winston Churchill in his book ‘The Story of the Malakand Field Force’

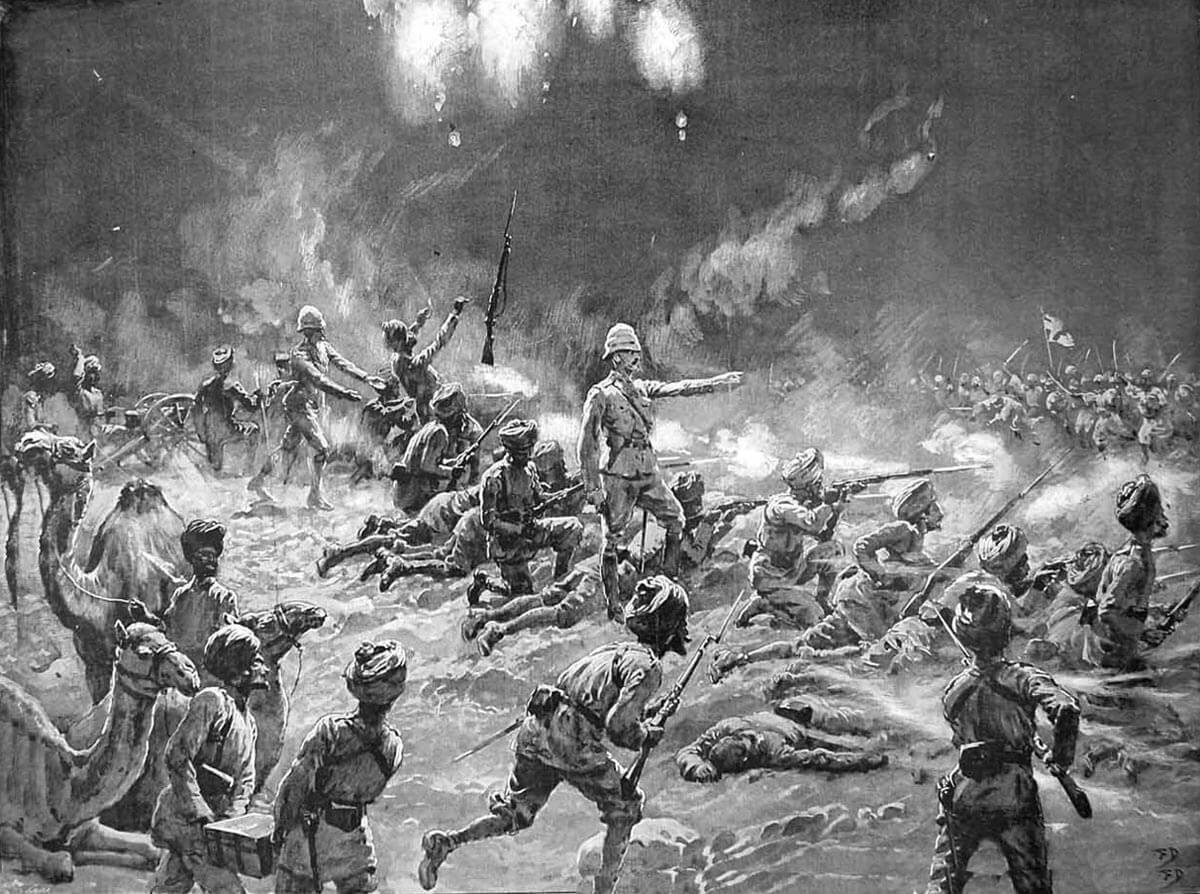

Night attack on the Nawagai Camp on 20th September 1897: Malakand Field Force, 8th September 1897 to 12th October 1897 on the North-West Frontier of India: picture by Frank Dadd

The previous battle of the North-West Frontier of India is the Malakand Rising 1897

The next battle of the North-West Frontier of India is the Mohmand Field Force 1897

To the North-West Frontier of India index

War: North-West Frontier of India.

Dates of the Malakand Field Force 1897: 8th September 1897 to 12th October 1897.

Place of the Malakand Field Force’s action in 1897 against the Mamunds: Bajaur and Mamund country; the area to the north of the Kabul River on the North-West Frontier of India, to the west of the Panjkora River, to the south of Jhar, to the east of the Afghan Border and to the north of Nawagai; essentially the Watelai Valley.

Combatants in the Malakand Field Force 1897: British and Indian troops against the Mamund tribe of Bajaur and their allies.

Note: the Mohmands and Mamunds are different tribes. The Mohmands occupy the area along the north bank of the Kabul River. The Mamunds are their immediate neighbours to the north. See the Mohmand Field Force 1897 for the simultaneous operation against the Mohmands by General Elles.

Commanders in the Malakand Field Force 1897: The Malakand Field Force was commanded by Major-General Sir Bindon Blood KCB.

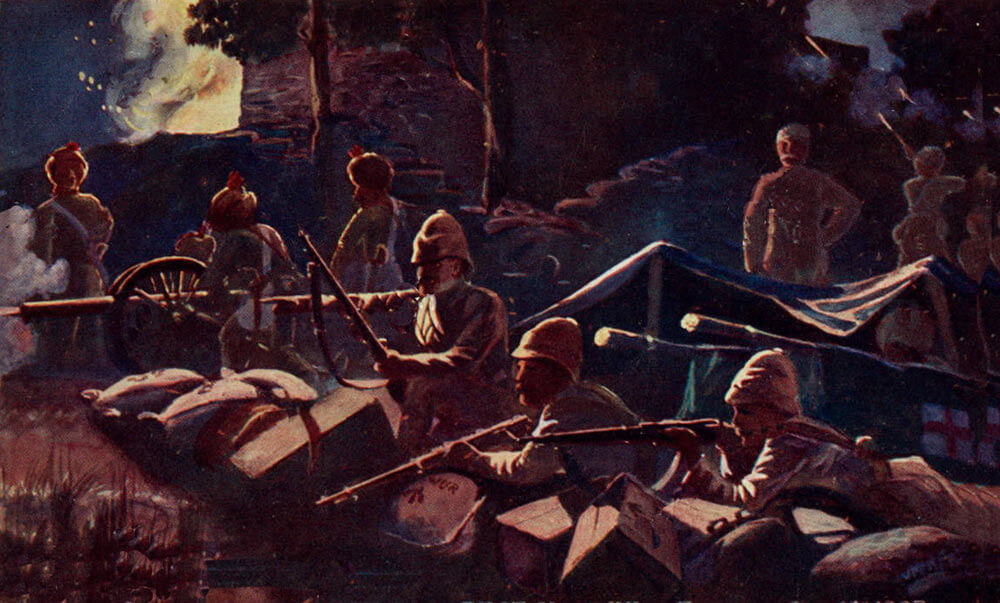

Lieutenant General Sir Bindon Blood (leaning on gun barrel) and his staff: Malakand Field Force, 8th September 1897 to 12th October 1897 on the North-West Frontier of India

An influential cleric in the Mohmand area to the south, was the Hadda Mulla. The Hadda Mulla may have influenced the neighbouring Mamunds; otherwise there does not seem to have been a particular leader of the Mamunds. As was often the case on the North-West Frontier, the Mamunds may have responded spontaneously and without particular direction, to defend their localities against the incursions of the British and Indian troops.

Size of the forces in the Malakand Field Force 1897: Each of the two brigades of the Malakand Field Force was probably able to put into the field around 1,000 effective troops.

The number of tribesmen in the field varied enormously from day to day. What is apparent is that the British command underestimated the numbers of tribesmen and their determination and high degree of competence in this form of mountain warfare.

Winner of the Malakand Field Force 1897: The British and Indian Army.

Uniforms, arms and equipment in the Malakand Field Force 1897:

The British military forces in India fell into these categories:

- Regiments of the British Army in garrison in India. Following the Indian Mutiny of 1857, India became a Crown Colony. The ratio of British to Indian troops was increased from 1:10 to 1:3 by stationing more British regiments in India. Brigade formations were a mixture of British and Indian regiments. The artillery was put under the control of the Royal Artillery, other than some Indian Army mountain gun batteries.

- The Indian Army comprised the three armies of the Presidencies of Bombay, Madras and Bengal. The Bengal Army, the largest, supplied many of the units for service on the North-West Frontier. The senior regimental officers were British. Soldiers were recruited from across the Indian sub-continent, with regiments recruiting nationalities, such as Sikhs, Punjabi Muslims, Pathans and Gurkhas. The Indian Mutiny caused the British authorities to view the populations of the East and South of India as unreliable for military service.

- The Punjab Frontier Force: Known as ‘Piffers’, these were regiments formed specifically for service on the North-West Frontier and were controlled by the Punjab State Government.

- Imperial Service Troops of the various Indian states, nominally independent but under the protection and de facto control of the Government of India. The most important of these states for operations on the North-West Frontier was Kashmir.

A British infantry battalion comprised 10 companies with around 700 men and some 30 officers. A battalion had a maxim machine gun detachment of 2 guns and around 20 men.

Colour Party of 45th Rattray’s Sikh Infantry: Malakand Field Force, 8th September 1897 to 12th October 1897 on the North-West Frontier of India

Indian infantry battalions had much the same establishment, without the Maxim gun detachment, although several of the battalions in the Malakand Field Force numbered only 400 to 500 all ranks. Senior officers were British, holding the Queen’s Commissions. Junior officers were Indian.

In 1897, Indian infantry regiments carried the single shot, drop action Martini-Henry breech loading rifle. British regiments had received the new Lee Metford bolt action magazine rifle from 1894.

By 1897, both Indian and British Royal Artillery Mountain Batteries used the RML (Rifled Muzzle Loading) 2.5 inch gun, the successor to the small, basic and unreliable RML 7 pounder gun, which had gone out of service in the British batteries in the early 1880s and, finally, in the Indian batteries in around 1895. The 2.5 inch had the nickname of ‘the Screw Gun’ as the barrel came in two sections that were screwed together for firing. The gun was dismantled for transport and carried by mules (see Kipling’s poem ‘the Screw Guns’).

British and Indian troops in 1897 wore khaki field dress when campaigning, with a leather harness to carry equipment and ammunition. British troops wore a pith helmet. Indian troops were largely turbaned. Gurkha troops wore a pill box hat. Scottish Highland regiments wore the kilt. Scottish Lowland Regiments, such as the Highland Light Infantry and the King’s Own Scottish Borderers, wore tartan trews.

The Indian cavalry regiments were armed with lance, sabre and carbine.

The standard tactic used by the British and Indian armies on the North-West Frontier of India, as with other so-called ‘semi-civilised enemies’ (tribesmen armed with swords and lances and with limited access to modern firearms), was to deliver a frontal attack, discharging controlled volleys of rifle fire and charging home with the bayonet. When stationary under fire, cover was taken behind sangars or low, stone-built walls.

Supporting fire was provided by artillery, where available. Cavalry conducted scouting duties and, in suitable circumstances, delivered mounted charges, which were particularly effective against loose formations of tribesmen caught in flat open country. The Indian cavalry regiments were adept at mixing mounted action with dismounted, in which carbine fire was used against tribesmen, particularly during a withdrawal.

When a military column moved through hostile country, great care had to be taken to ensure that flanking high ground was occupied in strength, until the column was clear of the area.

Withdrawal was when troops became most vulnerable. Experienced units made sure that withdrawal was made by alternate leaps, so that there was always a force providing covering fire for the troops moving back. Pathan tribes were quick to follow up British withdrawals and any error was immediately exploited. Many of the problems in battle for the British arose from inexperienced regiments failing to comply with the exacting requirements of frontier warfare.

Boy musicians, the Buffs: Malakand Field Force, 8th September 1897 to 12th October 1897 on the North-West Frontier of India

The regiment that could be relied upon fully for its stamina and extensive experience of Frontier warfare was the Queen’s Own Guides, comprising a cavalry regiment and an infantry regiment. Winston Churchill describes with admiration the actions of the Guides. When other regiments were in difficulties, the Guides came to their rescue. The Guides moved about the battlefield at speed. Only the Guides seemed able to conduct a withdrawal with impunity, in the face of tribal attack. When the British column withdrew to camp under attack, it was the Guides who provided the rear-guard and ensured that the exhausted soldiers of other regiments, collapsed on the way, were carried into camp.

The tribesmen fought on foot. It is estimated that, in the Malakand campaign, around a half were in possession of firearms: muskets, jezails, some Sniders (Enfield rifled muskets converted to breach loading) and a few Martini-Henry rifles. The tribesmen possessed no artillery or machine guns. Many fought with swords. Flags representing villages, clans and tribes were carried in battle as rallying points. Drums of many sorts were beaten; pipes and trumpets played.

A feature of warfare on the North-West Frontier of India was the ability of tribesmen to assemble in large numbers with little warning and to move at disconcerting speed across mountainous terrain, even at night.

Background to the Malakand Field Force 1897:

See Malakand Rising 1897 for the background.

Composition of the Malakand Field Force, 1897:

First Brigade (Brigadier General Meiklejohn)

1st Royal West Kent Regiment

24th Punjab Infantry

31st Punjab Infantry

45th Rattray’s Sikhs

Second Brigade (Brigadier General Jeffreys)

1st East Kent Regiment (Buffs)

35th Sikh Infantry

38th Dogras

Guides Infantry

Divisional Troops:

1 squadron 10th Bengal Lancers

11th Bengal Lancers

Guides Cavalry

No.1 Mountain Battery, RA

No.7 Mountain Battery, RA

No.8 Bengal Mountain Battery

22nd Punjab Infantry

2 companies of 21st Punjab Infantry

No.4 Company Bengal Sappers and Miners

No.5 Company Madras Sappers and Miners

Third (Reserve) Brigade (Brigadier General Wodehouse)

1st Queen’s Surreys

2nd Highland Light Infantry

6 companies of 21st Punjab Infantry

39th Garwhal Rifles

No.10 Battery, RA

No.3 Company Bombay Sappers and Miners

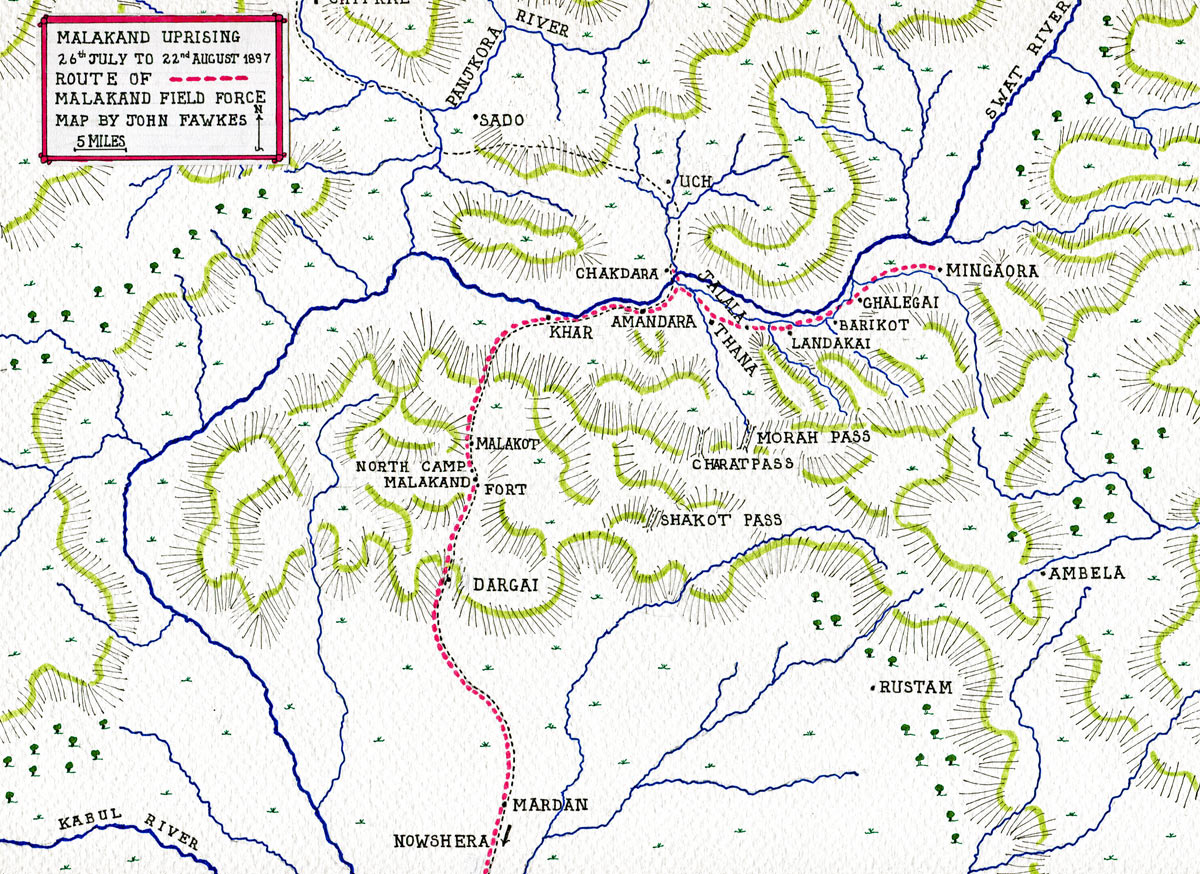

Map of the Malakand Rising, 26th July to 22nd August 1897 on the North-West Frontier of India: map by John Fawkes

Account of the Malakand Field Force 1897:

The attack by the various tribes on the Indian Army encampment in the Malakand Pass began on 26th July 1897.

The Government of India assembled a military force to relieve the Malakand garrison, under the command of Lieutenant General Sir Bindon Blood, giving it the title of ‘the Malakand Field Force’.

By 8th August 1897, the three brigades of the Malakand Field Force were assembled, the First Brigade, commanded by Brigadier General Meiklejohn, at Amandarra, the Second Brigade, commanded by Brigadier General Jeffreys, at Malakand and Khar and the Third Reserve Brigade, commanded by Brigadier General Wodehouse, at Mardan, watching the Bunerwal tribe to the east.

On that day news arrived of the Mohmand attack on Shabkadar Fort, led by the Hadda Mulla.

The attack on Shabkadar Fort was repelled, but the Hadda Mulla assembled a second force and advanced to attack the Nawab of Dir, in revenge for his support of the British.

As the Malakand Field Force moved up the Swat River to the north-east, the decision was made by the Government of India, that dealing with the Mohmands and the Mamunds, to the west, was a priority, requiring the diversion of the Malakand Field Force to act in concert with Major General Elles’s Mohmand Field Force, advancing north from Peshawar.

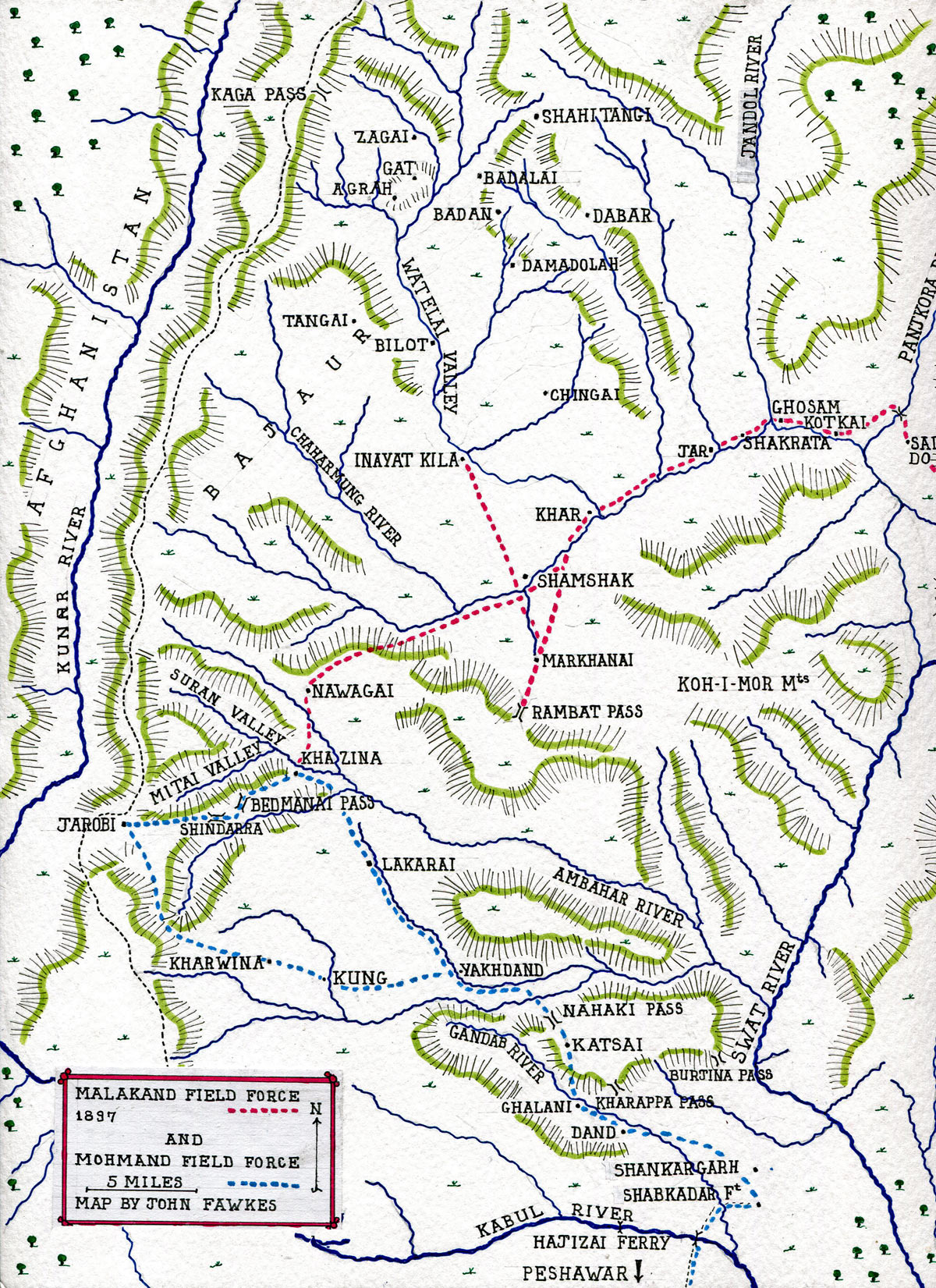

Map of the operations of the Malakand Field Force in Bajaur and the Mohmand Field Force in 1897: map by John Fawkes

On 30th August 1897, the Second Brigade of the Malakand Field Force returned from the upper Swat Valley and the Third Reserve Brigade crossed the Swat River to Uch.

These movements caused the Hadda Mulla’s incursion into Dir to peter out, but it was still felt by the British authorities that dealing with the Hadda Mulla and the Mohmands and Mamunds was a priority, to protect the Peshawar area to the south, in turmoil due to the tribal unrest and to ensure communications with Dir, Jandol and Chitral.

The area seethed with news of a general jihad against the British, the tribal mullahs giving out that the Amir of Afghanistan would lead the jihad in person, while accounts circulated of great successes by the Afridis against the British in the Kaibur area, to the south.

The plan was that while General Elles’s two brigades of the Mohmand Field Force marched north into the Mohmand tribal area, two of General Blood’s Malakand Field Force brigades would cross the Panjkora River and advance into Bajaur and through Nawagai, to support the Khans of Dir and Nawagai and inflict punishment on the hostile Mamund clans.

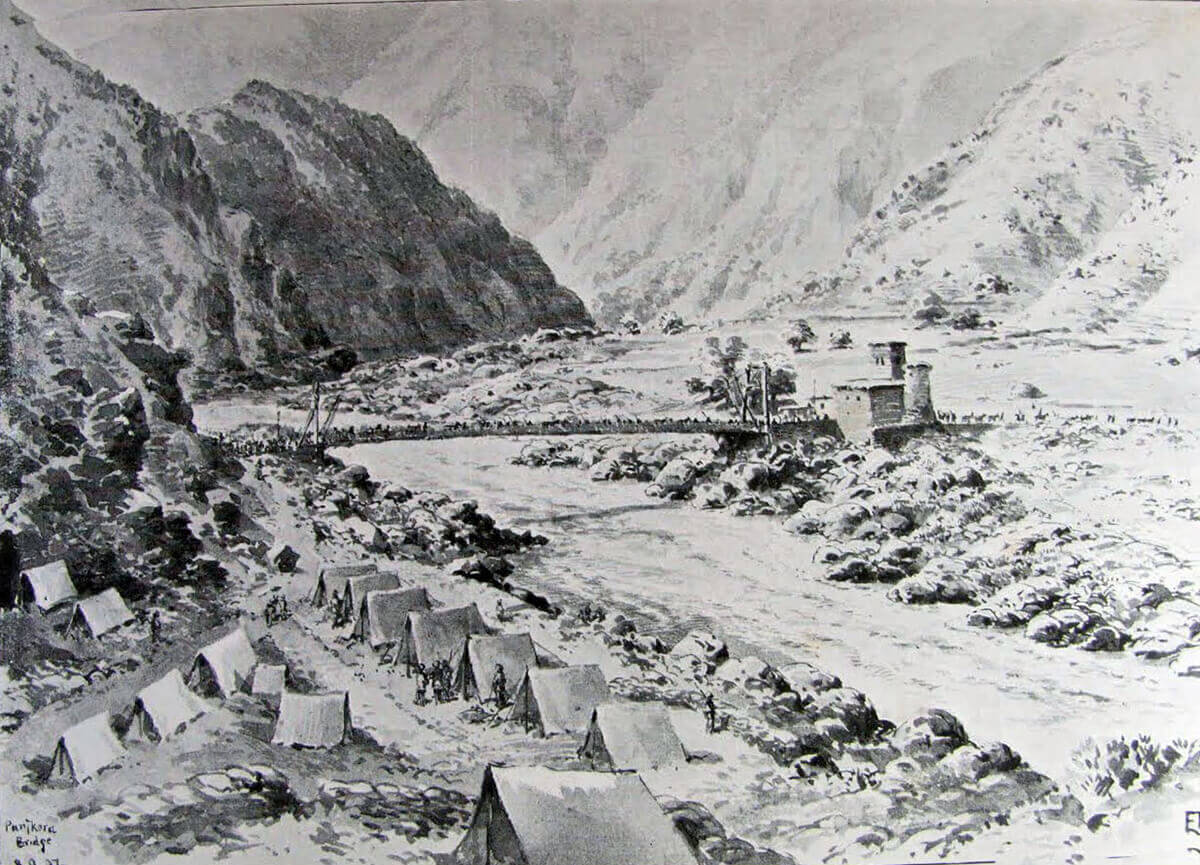

Panjkora River suspension bridge and camp: Malakand Field Force, 8th September 1897 to 12th October 1897 on the North-West Frontier of India: picture by Edmund Hobday

On 2nd September 1897, Brigadier General Wodehouse marched from Uch to seize the bridge over the Panjkora River at Sado. Further troops followed, giving Wodehouse a force comprising 1st Queen’s, 38th Dogras, 4 companies of 22nd Punjab Infantry, 2 squadrons of 11th Bengal Lancers, a half company of Sappers and Miners, 10th Field Battery and No.1 Mountain Battery, Royal Artillery.

It was discovered that the occupation of the Panjkora bridge, crucial for communications between the Swat Valley and Bajaur, was just in time to anticipate its seizure by hostile tribesmen. The securing of the bridge caused a number of Bajaur clans to abandon their intention to oppose the British, some chiefs even offering support.

General Blood received his orders to march into Bajaur on 3rd September 1897.

On 7th September 1897, General Blood took his divisional headquarters and the Second Brigade of the Malakand Field Force from Chakdara to Sarai. The First Brigade of the Malakand Field Force remained in the Swat Valley.

On 8th September 1897, General Blood and the Second Brigade crossed the Panjkora River and moved to Kotkai and, on the next day, to Ghosam. Here, the advance halted while an attempt was made to impose a penalty on the Shamozai Utman Khel, unsuccessfully.

At the same time, Major Deane, the political officer, conducted negotiations with the Jandolis and a number of khans in the valley. Relations of Umra Khan, the Jandoli khan responsible for acting against the British in Chitral in 1895, were taken and sent to Malakand, until they complied with terms imposed on them by the British.

On 10th and 11th September 1897, the Third Brigade concentrated at Shakrata and a section of the First Brigade moved up to Sado, to guard the Panjkora bridge and establish a forward depot.

On 12th September 1897, the Second Brigade advanced and camped at Khar in Bajaur, while Brigadier General Wodehouse’s Third Brigade moved to Shamshak, at the southern end of the Watelai valley. Wodehouse’s cavalry reconnoitered the Watelai and Chaharmung valleys and were shot at from Zagai village.

Some Mamund and Salarzai maliks came into the Third Brigade’s camp to enquire as to the British intentions, but there was no sign of any jirgas representing the tribes as a whole, which excluded any peace negotiations.

The Second Brigade’s transport animals were mules, while the Third Brigade used largely camels. This substantially dictated how the Third Brigade could be used, as the camels found the going in mountainous areas difficult, being significantly less agile than mules, while the rocks injured their soft feet.

General Sir Bindon Blood’s plan was to act in concert with General Elles’s Mohmand Field Force, that was advancing into Mohmand territory from the south, by advancing into Mohmand territory via Nawagai, while Brigadier General Jeffreys took part of the Second Brigade across the Rambat Pass to Butkor and Danish Kol, carrying out operations against the Mamunds.

On 14th September 1897 the Second Brigade occupied the Rambat Pass and then, leaving the Buffs with the company of Sappers and Miners to hold the pass, marched to Markhanai, where the brigade built a fortified camp near the village.

The attack on the Markhanai Camp on the night of 14th/15th September 1897:

The village of Markhanai belonged to the Manda Utman Khel, who had taken part in the fighting in the Swat Valley and were still hostile to the British authorities.

The Second Brigade built the form of rectangular field encampment, usual in hostile territory on the North-West Frontier; a rectangular walled enclosure, with the eastern wall along the edge of a steep sided nala, about sixty foot deep. The rest of the perimeter was in open country, except that about seventy yards from the wall on the western side, terraced fields sloped down to a nala, running northwards to a stream about a mile distant.

The troops bivouacked along the perimeter wall, ready to man the wall at short notice, the lesson learnt from the Wana Camp attack on 3rd November 1894, with the baggage and animals in the centre of the camp.

Sikh gunners of a mountain battery: Malakand Field Force, 8th September 1897 to 12th October 1897 on the North-West Frontier of India

At around 8pm, a signal of three shots rang out from the darkness, followed by a heavy fusillade from the east, west and north, causing heavy loss among the animals in the centre of the camp, but little or no injury to the troops, who hurriedly manned the perimeter wall, putting out cooking fires and other lights.

The tribal fire was directed mainly at the eastern face, held by the Guides Infantry. The area was lit by star shells, fired by the mountain battery and the troops responded to the tribesmen with volleys of rifle fire.

No charge was delivered, but the tribesmen used every item of cover to creep ever closer to the walls and deliver their fire, which was kept up until 10pm, when firing ceased. Signal fires could be seen, lit in a number of the surrounding villages.

The tribesmen resumed firing with renewed vigor at about 11pm and continued for three and a half hours. This time the firing was mainly on the western wall held by the 38th Dogras.

The Dogras were ordered not to fire back, in the hope that the tribesmen might be induced to charge the camp, enabling the troops to inflict heavy casualties on them. The tribesmen did not respond to this inducement and continued their galling fire on the garrison.

Brigadier General Jeffreys then ordered the 38th Dogras to charge the tribesmen.

As the 38th Dogras assembled for the attack, two British officers were shot dead, Captain Tomkins and Lieutenant Bailey and a third officer, Lieutenant Harrington, was seriously wounded. The attack was abandoned.

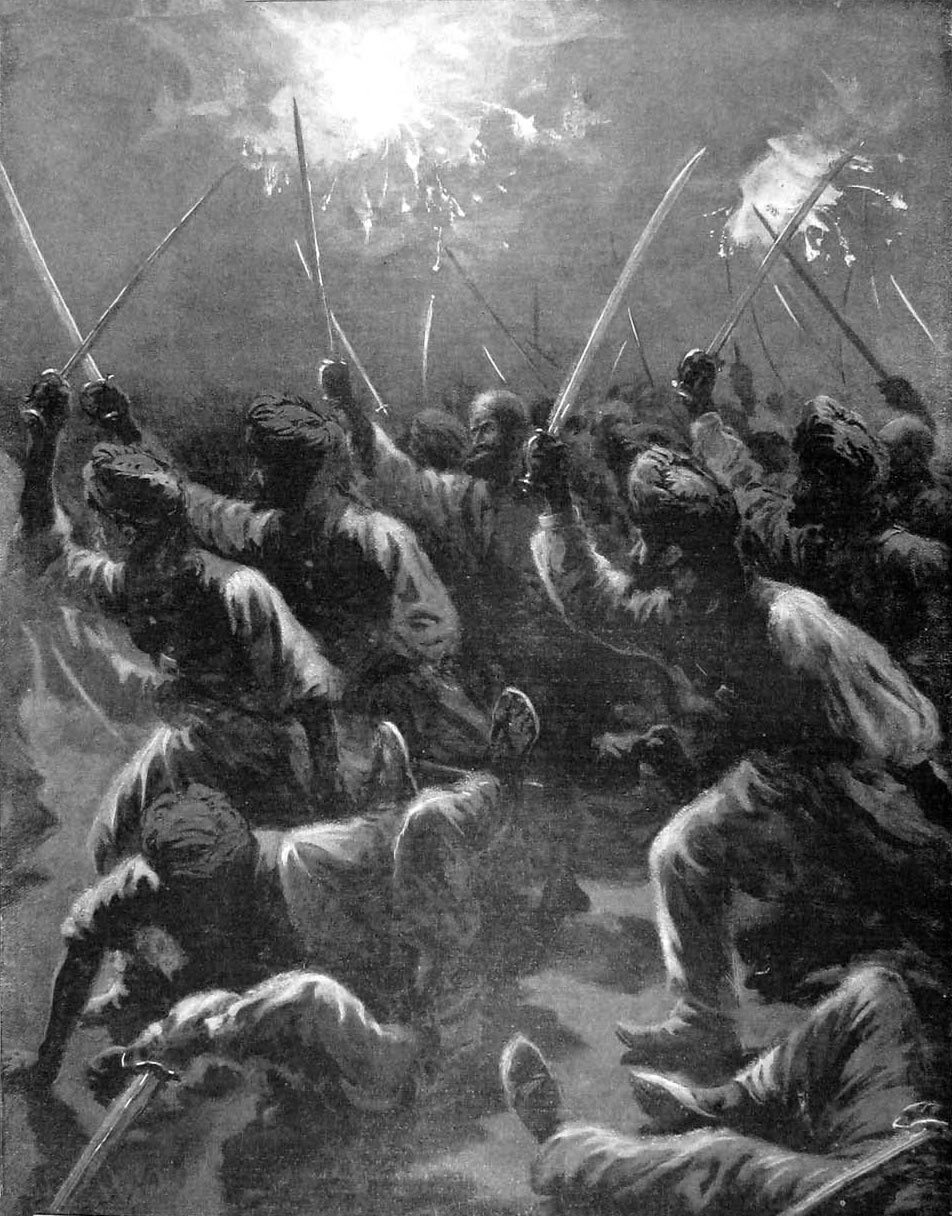

Night attack on the Nawagai Camp 19th and 20th September 1897: Malakand Field Force, 8th September 1897 to 12th October 1897 on the North-West Frontier of India: picture by WH Overend

It is hard not to conclude that Jeffreys made the same mistake he had, minutes before, been trying to induce the tribesmen to make.

Shortly afterwards the tribesmen withdrew. They had killed 2 British officers, 2 sepoys and 2 camp followers and wounded 1 British officer, 1 Indian officer and 9 soldiers. 98 horses and transport animals were killed or wounded.

The British authorities put together an accurate picture of the makeup of the attacking force of tribesmen. There were around 400 Mamund marksmen, with some Salarzai and Utman Khel, led by Muhammed Amin of Inayat Kila. Their casualties were 12 dead and an indeterminate number wounded.

The next morning, Captain Cole of the 11th Bengal Lancers set off in pursuit of the tribesmen responsible for the attack. The 11th caught up with them near the village of Badan Kot and killed 21 tribesmen, before driving the survivors into the hills around the Badan Gorge.

As the ground was becoming increasingly difficult for mounted troops, the Lancers withdrew towards camp, inevitably triggering the usual pursuit by the tribesmen. This pursuit ended and the tribesmen dispersed, when infantry support for the Lancers came up from Markhanai.

News of the attack on the Markhanai Camp was passed to General Blood at Nawagai. As soon as it was clear that the Mamunds were responsible for the attack on the camp, Brigadier General Jeffreys was ordered to abandon his intended move over the Rambat Pass and to march into Mamund country and administer punishment to the Mamunds.

On 15th September 1897, Brigadier General Jeffreys concentrated the Second Brigade at Inayat Kila, where a fortified camp was built as a base for the incursions against Mamund villages in the Watelai Valley.

Night attack on the Nawagai Camp on 20th September 1897: Malakand Field Force, 8th September 1897 to 12th October 1897 on the North-West Frontier of India: picture by WH Overend

Attack on Nawagai Camp:

General Sir Bindon Blood’s Third Brigade of the Malakand Field Force marched to Nawagai where they built an entrenched camp, to await the arrival of General Elles’s Mohmand Field Force and to ensure the continued loyalty of the Khan of Nawagai, under severe pressure to join the rising against the British.

The Nawagai Camp followed the same design as the Markhanai Camp. The camp was on stony terraced fields sloping away to the south. The ground was open to the north. On the east and west sides, there were dry nalas, about 200 yards from the perimeter wall, with the terraces providing cover to points near to the wall. Steep rocky hills were the backdrop to the west and the east.

The cavalry of the Third Brigade carried out reconnaissances to the Kandara, Ata Khel and Ambahar valleys.

On 15th and 16th September 1897, the cavalry found the Bedmanai Pass to be strongly held by tribesmen.

On 17th September 1897, news of the fighting against the Mamunds in the Watelai Valley and the difficulties of Jeffreys’ Second Brigade reached Nawagai, putting more pressure on the khan to join the rising, which he continued to resist.

On 18th September 1897, heliograph communication was established between the Malakand Field Force Third Brigade and General Elles’s Mohmand Field Force, now in the Nahaki Pass.

On 19th September 1897, General Blood received orders from Army Headquarters to leave Nawagai and join his Second Brigade at Inayat Kila. This was not feasible in view of his lack of strength and the need to defend the Khan of Nawagai, until the threat from the tribesmen in the Bedmanai Valley could be dealt with.

On the night of the 19th September 1897, some 2,000 of the Hadda Mulla’s tribesmen came down from the Bedmanai Pass and attacked the Nawagai Camp. They were easily repelled. British casualties were 1 killed and 1 wounded.

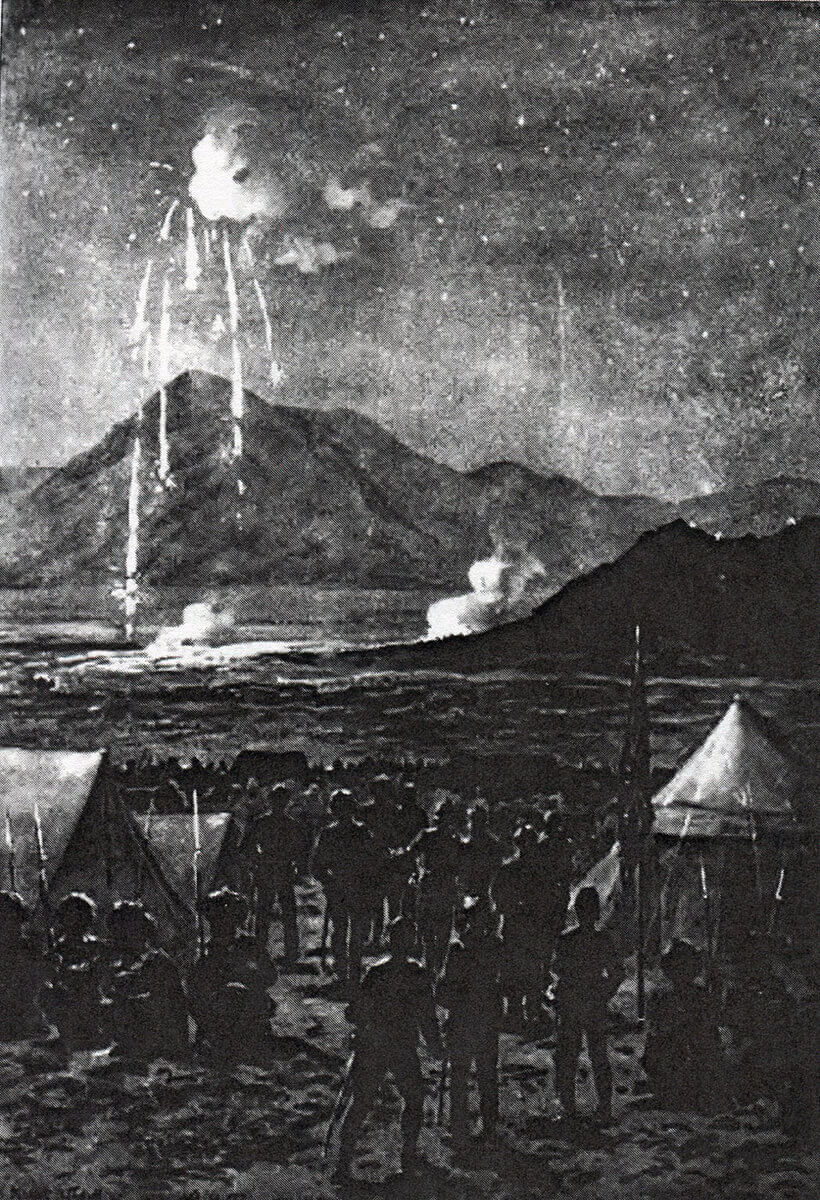

Night attack on the Nawagai Camp on 19th September 1897: Malakand Field Force, 8th September 1897 to 12th October 1897 on the North-West Frontier of India: drawing by Edmund Hobday

On the 20th September 1897, a second night attack was made on Nawagai Camp. Warning of the attack was given by the khan and the troops were ready.

Again, the tribesmen were from the Hadda Mulla’s gathering in the Bedmanai Pass. They were led by the Sufi Mulla of Baticot.

The attacks began from the north of the camp at around 9pm, with a charge by swordsmen, supported by rifle fire. Some 3,000 tribesmen were involved in the attacks, with a further 2,000 in reserve

The rushes were repeatedly made and driven off, on three sides of the camp, until they ceased at around 2am. The swordsmen were determined and many were shot down within a few yards of the wall, but no tribesmen penetrated the defences.

The troops responded with disciplined volley firing, the guns firing star shells into the sky to illuminate the area.

Night attack on the Nawagai Camp on 20th September 1897: Malakand Field Force, 8th September 1897 to 12th October 1897 on the North-West Frontier of India: picture by Edmund Hobday

The casualties among the tribesmen are believed to have been around 350 killed and a large number wounded. Several leaders among the tribesmen are known to have been killed.

British casualties were 1 killed and 31, including Brigadier General Wodehouse, wounded.

The next morning, the cavalry set off in pursuit, but did not make contact with the tribesmen, who must have dispersed into the mountains.

On 21st September 1897, General Blood met General Elles at Lakarai. The Third Brigade of the Malakand Field Force (1st Queen’s, 22nd Punjab Infantry, 39th Garwhal Rifles, 1 squadron 11th Bengal Lancers, No.1 Mountain Battery, RA and No.3 Company Bombay Sappers and Miners), now commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Graves of 39th Garwhalis, marched to Kuz Chinari and joined the Mohmand Field Force to attack the Hadda Mulla’s tribesmen in the Bedmanai Pass and in Jarobi.

Once the operation was completed, the Third Brigade marched to Peshawar and joined the Tirah Expeditionary Force.

Second Brigade, Malakand Field Force:

On 16th September 1897, Brigadier General Jeffreys’ Second Brigade marched out from the camp at Inayat Kila up the Watelai Valley in three columns. Number One Column comprised 1 squadron 11th Bengal Lancers, 4 guns No.8 Mountain Battery, 4 companies the Buffs, 6 companies 35th Sikhs and part of No.4 Company, Bengal Sappers and Miners, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Goldney, 35th Sikhs. Number Two Column comprised 6 companies 38th Dogras and part of No.4 Company, Bengal Sappers and Miners, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Vivian, 38th Dogras. Number Three Column comprised 2 companies the Buffs, 5 companies the Guides Infantry and part of No.4 Company, Bengal Sappers and Miners.

Number One Column was to advance up the Kaga Pass road to Badalai. Number Two Column was to move in parallel along the eastern foothills. Number Three Column was to march towards Agrah. All three columns would destroy villages on their march.

Colonel Vivian’s Number Two Column reached Damadolah, where it encountered strong opposition and, having insufficient strength and no guns, Vivian withdrew to the camp, reaching Inayat Kila at 4pm with insignificant casualties.

Numbers One and Three Columns moved up the valley. At 7.30am, the cavalry patrols reported that the tribesmen were holding Badan. Lieutenant Colonel Ommaney was ordered forward with 4 companies of the Buffs and 2 guns to take the village. The tribesmen fell back before the Buffs to Dabar.

In the meanwhile, Colonel Goldeney, with the rest of Number One Column, reached Badalai, where he received a report from the cavalry that the tribesmen were gathering in strength in the west.

Goldeney stopped short of Badalai and ordered Ommaney to rejoin the column with his men.

General Jeffreys then received information that the tribesmen were moving up the valley towards the Kaga Pass and ordered Goldeney to intercept them and prevent them from entering the pass, without waiting for Ommaney’s companies. A message was sent to Major Campbell, ordering him to bring his column up on the left of Goldeney’s centre column.

The tribesmen were driven out of Badalai and Captain Ryder with 1 ½ companies of 35th Sikhs moved up the hill to the east of Badalai, to protect the column’s flank, followed by the guns with an escort of a further 1 ½ companies.

The rest of the 35th Sikhs pushed on to Shahi Tangi, stopping there at 10.30am to allow the Buffs to come up.

35th Sikh Infantry at Shahi Tangi on 16th September 1897: Malakand Field Force, 8th September 1897 to 12th October 1897 on the North-West Frontier of India: picture by William Barnes Wollen

With the halt of the troops, the tribesmen turned to the attack, pressing hard the Sikhs in Shahi Tangi and compelling Goldeney to order his regiment to retire. 2 of his companies were too far forward and found themselves in difficulties.

As could happen quickly in frontier warfare, a successful advance halted, in a moment turned into a position of peril.

As the 35th Sikhs withdrew towards Chingai, a body of tribesmen advanced into the open country to cut them off. Fortunately for Goldeney’s men, Captain Cole’s squadron of 11th Bengal Lancers was in the right position and charged the tribesmen, dispersing them and enabling the Sikhs to break through with the bayonet.

At about the same time, the companies of the Buffs came up and the mountain guns came into action from the ridge above Chingai.

Major Campbell’s column of Buffs and Guides Infantry occupied a position that enabled them to check the advance of a large body of tribesmen coming from the western side of the valley to join their brothers at Shahi Tangi.

In their withdrawal from Shahi Tangi, the 35th Sikhs suffered casualties of Lieutenant Hughes and a sepoy being killed and Lieutenant Cassels and 16 sepoys being wounded.

At midday, the 35th Sikhs and the Buffs returned to the attack, with support from the guns, destroying Shahi Tangi and Chingai. This was completed by 2.30pm and losses inflicted on the tribesmen, who are described as maintaining a stubborn resistance.

Brigadier General Jeffreys now began the difficult operation of withdrawing his troops, heavily engaged with the tribesmen, back to the camp at Inayat Kila, with the imperative of reaching the camp before darkness.

35th Sikh Infantry withdrawing under attack on 16th September 1897: Malakand Field Force, 8th September 1897 to 12th October 1897 on the North-West Frontier of India: picture by Edmund Hobday

Orders to retire failed to reach Captain Ryder with his 1 ½ companies of Sikhs, on the high ground on the right flank. Not until he saw the main body withdrawing at around 3.30pm, did Captain Ryder begin his own withdrawal. As usual in frontier warfare, this withdrawal drew down on his men a prompt and violent attack by the tribesmen.

Although Ryder’s Sikhs inflicted heavy casualties on the pursuing tribesmen, they suffered significant casualties themselves, amounting to 15 killed, 3 missing and 24 wounded, including both the British officers and 2 Indian officers. As the wounded and if possible the bodies of the slain had to be carried back, more sepoys were taken out of action and the retreat greatly impeded.

Brigadier General Jeffreys halted the general withdrawal to give Ryder’s Sikhs the opportunity to catch up and, once they seemed to be in safety, the retreat continued, approaching the villages of Munar and Bilot at around 7pm. Here 4 additional companies, 2 of Guides and 2 of 45th Sikhs commanded by Major Worledge, arrived from the camp at Inayat Kila and were sent on to support the rearguard of Guides Infantry, whose volleys at the pursuing tribesmen could be heard in the distance.

The Buffs, in extended order, reached Munar, while the mountain battery, the Sappers and Miners with a company of the 35th Sikhs were approaching Bilot.

General Jeffreys with Corporal Smith and his party of 1st Buffs, No.8 Bengal Mountain Battery and No.4 Company, Bengal Sappers and Miners at Bilot on the night of 16th September 1897: Malakand Field Force, 8th September 1897 to 12th October 1897 on the North-West Frontier of India

The action in Bilot:

Darkness was now falling and Jeffreys issued orders to occupy Munar and Bilot for the night, to enable the troops on the right flank to fall back. The difficulty in controlling the brigade was increased by a heavy thunderstorm.

The Buffs failed to receive the order and continued back to the camp at Inayat Kila, leaving the general with No.8 Bengal Mountain Battery, the Sappers and Miners and a party of 12 Buffs that had been detached to escort a dooli carrying a wounded officer, which in the event they could not find. The Sikhs escorting the guns lost touch and continued back to camp.

The action at Bilot on the night of 16th September 1897: Malakand Field Force, 8th September 1897 to 12th October 1897 on the North-West Frontier of India

Anticipating General Jeffrey’s intentions, the tribesmen occupied Bilot, forcing the British troops to take what cover they could under a heavy fire. The guns fired at the tribesmen from close range and the night was spent with the Sappers and Miners and the 12 Buffs attempting to clear the village, led by Lieutenant Watson RE and Lieutenant Colvin RE.

Corporal James Smith VC, 1st Buffs: Malakand Field Force, 8th September 1897 to 12th October 1897 on the North-West Frontier of India

Corporal Smith of the Buffs particularly distinguished himself in the repeated charges on the tribesmen.

At around midnight, Major Worledge arrived with his 4 companies of Guides and Sikhs, having failed to make contact with the Guides Infantry and the tribesmen were then forced out of Bilot. The force passed the rest of the night without further attack and a relieving force, of which Winston Churchill was a member, arrived in the morning.

During the fighting on 16th September 1897, Brigadier Jeffreys’ Second Brigade suffered casualties of 2 officers (Lieutenant Hughes, 35th Sikhs and Lieutenant Crawford RA of the mountain battery) and 36 soldiers killed and 11 officers, 102 soldiers and 2 camp followers wounded.

Over the following days, troops burnt a number of villages in the area of the camp at Inayat Kila.

Lieutenant Watson VC Royal Engineers: Malakand Field Force, 8th September 1897 to 12th October 1897 on the North-West Frontier of India

On 20th September 1897, a battle took place at the village of Zagai, with ex-retainers of Umra Khan of Jandol, the leader of the attack on the British in Chitral Fort in 1895 (see the Siege of Chitral).

While retiring from Zagai over difficult ground, the Buffs were closely pressed by these tribesmen. Once the troops reached more open country, the tribesmen were driven off with heavy loss. 4 Buffs officers and 10 soldiers were wounded.

On 23rd September 1897, the village of Tangai was destroyed by the troops. This involved a large operation, to prevent the tribesmen from intervening, with the Buffs, the 35th Sikhs and the mountain guns providing a covering force for the Dogras and Sappers who went into the village.

Also on that day, the Khan of Jhar came into camp to request a truce, while terms were discussed with the Mamunds. The truce was agreed and extended to 28th September 1897.

Lieutenant Colvin VC, Royal Engineers: Malakand Field Force, 8th September 1897 to 12th October 1897 on the North-West Frontier of India

During the truce, an exchange of regiments for the somewhat battered Second Brigade took place, with No.8 Bengal Mountain Battery, the Buffs and 35th Sikhs returning to the depot camp on the Panjkora, being replaced by 2 squadrons of Guides Cavalry, No.7 Mountain Battery, RA, 2nd Royal West Kents and 31st Punjab Infantry.

On 28th September 1897, reports circulated that the Mamunds were about to attack the Inayat Kila camp. This did not happen, but further reports made it clear that the request for the truce, on the basis that the Mamunds were proposing to seek terms of peace was false. The tribesmen needed the temporary cessation of hostilities to remove their belongings from vulnerable villages to higher ground and to sow their land.

Action at Agrah and Gat:

On 29th September 1897, a powerful force, comprising the Guides Cavalry, No.7 Mountain Battery, RA, 1st Royal West Kent Regiment, 31st Punjab Infantry, 38th Dogras and the Guides Infantry, led by Brigadier General Jeffreys, the brigade commander, marched up the valley to attack Agrah and Gat.

As the troops approached the villages, a large force of tribesmen could be seen on the high ground to the west, in a position of considerable strength, with more tribesmen joining them.

A rocky precipitous ridge divided the space between Agrah and Gat, while on either flank were steep boulder-strewn spurs, commanding the ground over which the troops would advance.

The Guides Cavalry began the attack, advancing along the Kakazai Nala, for some distance up the mountainside and then, dismounting and opening rifle fire on the tribesmen.

The main attack required the Guides Infantry to advance up the western spur, with the Royal West Kents on their right, advancing through the gap between the two villages to a position in the rear of Agrah. The 31st Punjab Infantry were to occupy the rocky ridge between the villages. The Dogras remained in reserve.

The mountain guns opened fire from the bank of a nala, a mile and a half south of Gat, in support of the 31st Punjab Infantry, bombarding the tribesmen holding the rocky ridge.

1st Royal West Kents at Agrah and Gat on 29th September 1897: Malakand Field Force, 8th September 1897 to 12th October 1897 on the North-West Frontier of India: picture by Walter Paget after Lionel James

The tribesmen held their positions on the ridge with great determination and had to be driven out by the 31st Punjab Infantry, at the point of the bayonet. In the course of the attack, the commandant of the battalion, Lieutenant Colonel O’Bryen, a particularly promising officer, received a mortal wound from which he later died.

To assist the 31st Punjab Infantry in their difficult and heavily resisted attack, Brigadier General Jeffreys moved 2 companies from the reserve to a knoll on their right, to provide support and ordered the mountain guns to move half a mile forward and shell the ground east of Gat, to cut off the route for tribal reinforcements into Gat.

The Guides Infantry were heavily involved in checking the tribesmen to the front and left flank. The Royal West Kents advanced onto the ridge above Agrah and, from there, covered the Sappers and Miners as they destroyed the village.

Once the destruction of Agrah was complete, the Royal West Kents moved east to support the 31st Punjab Infantry and encountered numbers of tribesmen positioned in stone sangars, who resisted their advance fiercely.

Royal Artillery gunners at Panjkora: Malakand Field Force, 8th September 1897 to 12th October 1897 on the North-West Frontier of India

As a party of Royal West Kents cleared a sangar, Lieutenant Clayton Browne was killed and several men wounded. A force of swordsmen charged the troops and drove them out of the sangar, whereupon the supporting company of the Royal West Kents advanced with the bayonet and dispersed the tribesmen.

By now, Gat was partially destroyed, but more tribesmen were advancing from Zai and the commanding officer of the Royal West Kents considered it prudent to withdraw his battalion.

Once clear of Gat, the whole force retired to the camp at Inayat Kila, arriving at 4.30pm.

British casualties on the day were 2 officers and 10 men killed with 7 officers and 42 men wounded. Tribal casualties were severe. 4 leading maliks were known to have been killed and there were many dead bodies in and around Gat.

It was now apparent that Brigadier General Jeffreys’ Second Brigade was not strong enough to compel the Mamunds to submit.

On 2nd October 1897, General Sir Bindon Blood left the Panjkora depot for the camp at Inayat Kila with a squadron of Guides Cavalry, No.8 Bengal Mountain Battery and 4 companies of 24th Punjab Infantry.

Brigadier General Meiklejohn followed, with 10th Field Battery, RA, armed with 12 pounder field guns, No.5 Company Madras Sappers and Miners and 2nd Highland Light Infantry, arriving at Inayat Kila on 4th October 1897.

1st Royal West Kents after the fight at Agrah and Gat on 29th September 1897: Malakand Field Force, 8th September 1897 to 12th October 1897 on the North-West Frontier of India

On 2nd October 1897, Brigadier General Jeffreys marched out of Inayat Kila in the direction of Agrah and Gat with much the same force as in his previous operation on 29th September 1897, with the addition of No.8 Mountain Battery, RA.

Expecting the attack to fall again on Agrah and Gat, to complete the destruction of Gat, the tribesmen gathered in strength on the hills above the village.

But Jeffreys’ column turned off to the right and headed for the village of Badalai. Badalai was destroyed and Jeffreys’ column was on the return march to Inayat Kila, when the tribesmen came up from the direction of Chingai and attempted to envelope the British column, but were checked by the cavalry and the fire of the infantry.

Second Brigade casualties in this operation were 2 men killed and 17 men wounded.

On 4th October 1897, with the arrival of the fresh troops in Inayat Kila, the two brigades and the divisional reserve were re-organised.

The Mamunds were aware of the arrival at Inayat Kila of the significant number of fresh troops and realised that the Government of India intended to devote whatever resources were necessary to defeat them. The Khan of Nawagai was requested to act as go-between in negotiating a peace settlement.

In view of the substantial casualties the Mamunds had suffered in the fighting and the number of villages and crops that had been destroyed, the sole requirement made of the tribe was to return all the rifles captured from British and Indian troops during the fighting. This was done and the Mamunds sent all their allies, from outside the area, back to their homes.

To ensure the preservation of the new peace, the Mamunds picketed the British camps to ensure they were not attacked or sniped at.

The Afghan general, Sipah Salar, attempted to persuade the Mamunds not to return the rifles captured, but this was done.

On 11th October 1897, Sir Bindon Blood received the Mamund jirga in durbar. A declaration was read and hostilities were closed.

General Blood meets the Mamund jirgas in durbar with the Khans of Nawagai, Jhar and Khar on 11th October 1897: Malakand Field Force, 8th September 1897 to 12th October 1897 on the North-West Frontier of India: drawing by Edmund Hobday

On 12th October 1897, the Malakand Field Force left the Watelai Valley and marched to Jhar.

Casualties in the Malakand Field Force 1897: From 14th September to 11th October 1897, the Second Brigade of the Malakand Field Force suffered casualties of 6 officers killed and 24 officers wounded, 55 non-commissioned officers and men killed and 194 wounded. 135 horses and mules were killed or lost.

The tribesmen were estimated to have suffered casualties of 300 killed and 250 wounded.

Battle Honour and decorations for the Malakand Field Force 1897:

The Indian General Service Medal 1895, with the clasp ‘Punjab Frontier, 1897-98’ was awarded to all ranks who had taken part in the operations in Bajaur and Mamund country.

The battle honour ‘Malakand’ was awarded by the Government of India to the Indian Army regiments of the garrison of Malakand that was attacked on 26th July 1897 (see Malakand Rising 1897).

Follow-up to the Malakand Field Force 1897:

Following the operation against the Mamunds in the Watelai Valley, the Malakand Field Force moved north to deal with the Salarzai, who sued for peace without resistance and then to Jhar, where the Shamozai Utman Khels came to terms.

The Khans of Nawagai, Khar and Jhar received substantial financial rewards for their support of the British.

The Malakand Field Force was broken up on 19th January 1898.

The Government of India record of the Malakand Field Force campaign in Bajaur in 1897 stated: ‘The stubborn defence of their country in spite of continuous losses, gained for the Mamunds a well deserved reputation for bravery and good fighting qualities.’

Winston Churchill: Malakand Field Force, 8th September 1897 to 12th October 1897 on the North-West Frontier of India

Winston Churchill: Churchill was serving in India as a subaltern officer in the 4th Hussars, stationed at Bangalore. With the outbreak of the risings on the North-West Frontier in 1897 and no prospect of any British cavalry regiment being involved, Churchill obtained an appointment as war correspondent for the Daily Telegraph. Churchill arrived in Swat as the Malakand Field Force was about to begin the attack on Bajaur, recounted on this page. Churchill’s book ‘the Malakand Field Force’, while recording the events surrounding the attack on Malakand, went on to become a record of his personal experiences in battle after the crossing of the Panjkora River.

Churchill was present on 16th September 1897 with Jeffrey’s Second Brigade, initially with Captain Coles’ 11th Bengal Lancers squadron and then with the 35th Sikhs, as they carried out their attack on Shahi Tangi. The next morning, Churchill was with the party that relieved Brigadier General Jeffreys in Bilot. Straight forward history became a graphic eye witness account.

Churchill’s book contains sections on the tactics of fighting on the North-West Frontier and his analysis of the problems thrown up by the area’s complex politics.

The Victorian Distinguished Conduct Medal: 4 soldiers of the Buffs were awarded the DCM for their conduct at Bilot, on the night of 16th September 1897: Malakand Field Force, 8th September 1897 to 12th October 1897 on the North-West Frontier of India

Churchill considered the loss of officers. Marked out by their swords and lack of rifles and in the Indian regiments their distinctive headgear (helmets not turbans), the officers were a prime target for the tribesmen. Churchill wrote: ‘When the Buffs were marching down to Panjkora, they passed the Royal West Kent coming up to relieve them at Inayat Kila. A private in the up-going regiment asked a friend in the Buffs what it was like at the front. ‘Oh’, replied the latter, ‘you’ll be all right so long as you don’t go near no officers, nor no white stones.’ Whether the advice was taken is not recorded, but it was certainly sound, for three days later -on 30th September- in those companies that were engaged in the village of Agrah, eight out of eleven officers were hit or grazed by bullets’.

The British army was to find just how vulnerable its officers were to enemy marksmen with the outbreak of the Boer War, two years later.

Bilot:

Lieutenants Watson and Colvin and Corporal Smith were awarded the Victoria Cross for their conduct in Bilot.

The Distinguished Conduct Medal was awarded to Privates Lever, Poile, Finn and Nelthorpe from the party of the Buffs.

Anecdotes and traditions from the Malakand Field Force 1897:

- One of the medical officers tending the wounded in Nawagai camp during the tribal attacks was Captain Whitchurch, who had won the Victoria Cross in the Chitral garrison in 1895.

- The firing of three shots was the tribesmen’s signal for the attack on Markhanai Camp on 14th September 1897. Three shots fired seems to have been a standard signal among the tribesmen for a night attack. A similar signal began the attack on the Wana Camp on 3rd November 1894.

- It was widely acknowledged in Indian military circles that the Mamunds resistance was unexpectedly strong. There were times during the Second Brigade’s operation in the Watelai Valley, when the British and Indian troops came near to disaster. Captain Ryder’s 35th Sikhs were rescued in the nick of time by the indomitable Guides and, if General Jeffreys had not encountered Corporal Smith’s group of 12 Buffs and Major Worledge had not found the general in the dark, Jeffreys, a battery of mountain guns and a company of Sappers and Miners might well have been overwhelmed by the tribesmen at Bilot on the night of 16th September 1897.

- Although nothing is said in the official history, it seems likely that General Blood was considered to have mishandled the operations against the Mohmands and Mamunds and to have run unnecessary and potentially disastrous risks, by dividing his force.

- The British infantry battalions, armed as they were with the magazine Lee-Metford rifle, were a significant force on the battlefield.

References for the Malakand Field Force 1897:

Frontier and Overseas Expeditions from India Volume 1 published by the Government of India

North West Frontier by Captain H.L. Nevill DSO, RFA

The Story of the Malakand Field Force by Winston Churchill

The North-West Frontier by Michael Barthorp

The Frontier Ablaze, the North-West Frontier Rising 1897-1898 by Michael Barthorp

The History of Probyn’s Horse (11th and 12th Bengal Lancers)

Sketches on service during the Indian Frontier Campaigns of 1897 by Edmund Hobday

The previous battle of the North-West Frontier of India is the Malakand Rising 1897

The next battle of the North-West Frontier of India is the Mohmand Field Force 1897

To the North-West Frontier of India index