Admiral Nelson’s victory over the French Fleet on 1st August 1798 that made him a household name throughout Europe

French Flagship L’Orient explodes at 10pm during the Battle of the Nile on 1st August 1798 in the Napoleonic Wars: picture by George Arnald

The previous battle in the Napoleonic Wars is the Battle of Cape St Vincent

The next battle of the Napoleonic Wars is the Battle of Alexandria

Rear Admiral of the Blue Sir Horatio Nelson British commander at the Battle of the Nile on 1st August 1798 in the Napoleonic Wars: Nelson is wearing the aigrette awarded to him by the Sultan of Turkey following the battle

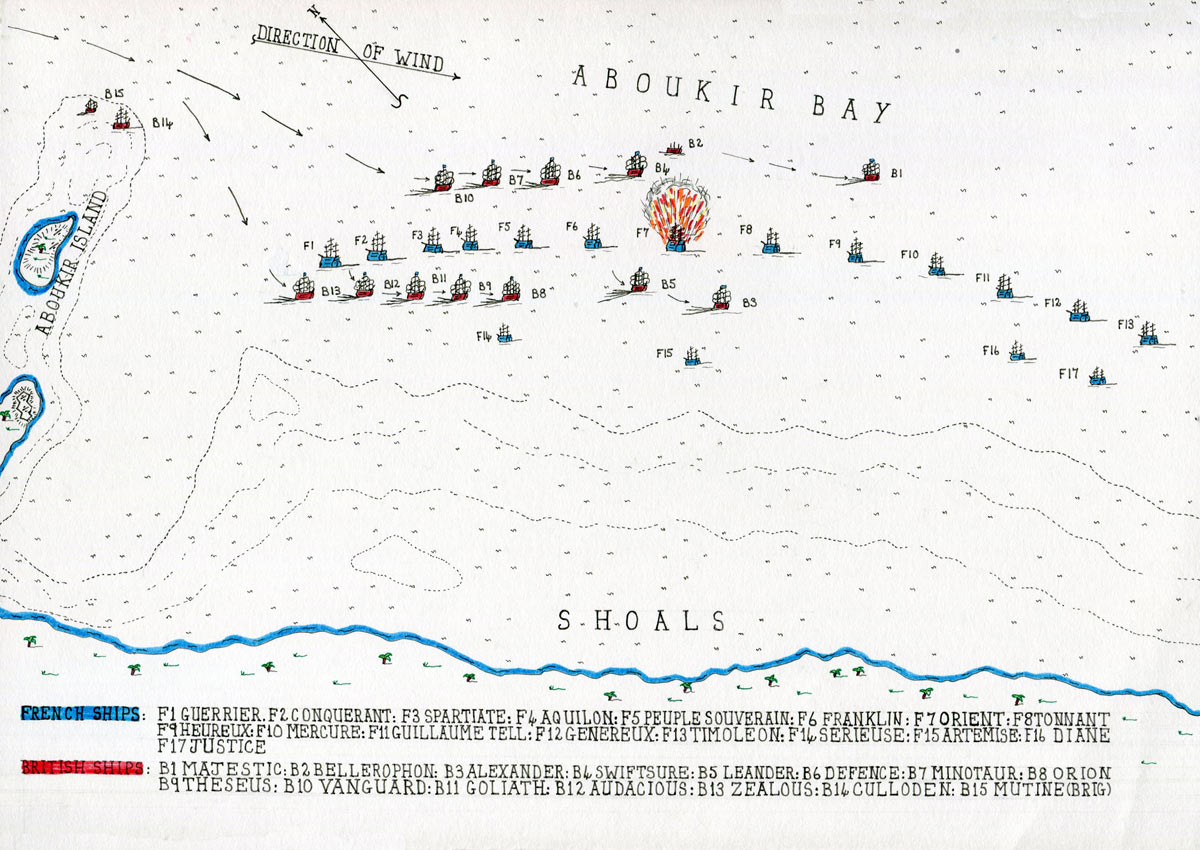

Battle: The Nile or Aboukir Bay.

War: Napoleonic Wars.

Date of the Battle of the Nile: 1st August 1798.

Place of the Battle of the Nile: East of Alexandria off the coast of Egypt in the Mediterranean.

Combatants at the Battle of the Nile: A British Fleet against a French Fleet.

Commanders at the Battle of the Nile: Rear Admiral of the Blue Sir Horatio Nelson against Admiral Brueys d’Aigalliers.

Winner of the Battle of the Nile: Nelson and the British Fleet won a resounding victory, arguably one of the decisive battles of naval warfare.

The Fleets at the Battle of the Nile:

Admiral Brueys d’Aigalliers French commander killed at the Battle of the Nile on 1st August 1798 in the Napoleonic Wars

The British Fleet, His Majesty’s Ships Vanguard (Nelson’s Flagship: Captain Berry, 74 guns), Majestic (Captain Westcott, 74 guns), Bellerophon (Captain Darby, 74 guns), Defence (Captain Peyton, 74 guns), Orion (Captain Saumarez, 74 guns), Minotaur (Captain Louis, 74 guns), Theseus (Captain Miller, 74 guns), Goliath (Captain Foley, 74 guns), Audacious (Captain Gould, 74 guns), Zealous (Captain Hood, 74 guns), Leander (Captain Thompson, 50 guns), Swiftsure (Captain Hallowell, 74 guns), Alexander (Captain Ball, 74 guns), Culloden (Captain Troubridge, 74 guns) and Mutine (Captain Hardy, 74 guns).

The French Fleet, L’Orient (Flagship: Commodore Casabianca, 120 guns), Guerrier (Captain Trullet, 74 guns), Conquerant (Captain D’Albarde, 74 guns), Spartiate (Captain Eimeriau, 74 guns), Aquilon (Captain Thevenard, 74 guns), Peuple Souverain (Captain Raccord, 74 guns), Franklin (Flagship of Admiral Hayla: Captain Gillet, 80 guns), Tonnant (Captain Thouars, 80 guns), Heureux (Captain Etienne, 74 guns), Mercure (Captain Cambon, 74 guns), Guillaume Tell (Admiral Villeneuve’s Flagship: 80 guns), Genereux (Captain Lenoille, 74 guns), Timoleon (Captain Trullet [jeune], 74 guns), Frigates, Serieuse (Captain Martin, 36 guns), L’Artemise (Captain Estandlet, 36 guns), Diane (Admiral de Crepe: Captain Soleil, 36 guns) and Justice (Captain Villeneuve, 40 guns).

The French Fleet of 13 ships of the line and 4 frigates carried 1,196 guns. The British Fleet of 13 ships of the line and one 50 gun ship carried 1,012 guns.

Ships and Armaments at the Battle of the Nile:

Life on a sailing warship of the 18th and 19th Century, particularly the large ships of the line, was crowded and hard. Discipline was enforced with extreme violence, small infractions punished with public lashings. The food, far from good, deteriorated as ships spent time at sea. Drinking water was in short supply and usually brackish. Shortage of citrus fruit and fresh vegetables meant that scurvy quickly set in. The great weight of guns and equipment and the necessity to climb rigging in adverse weather conditions frequently caused serious injury.

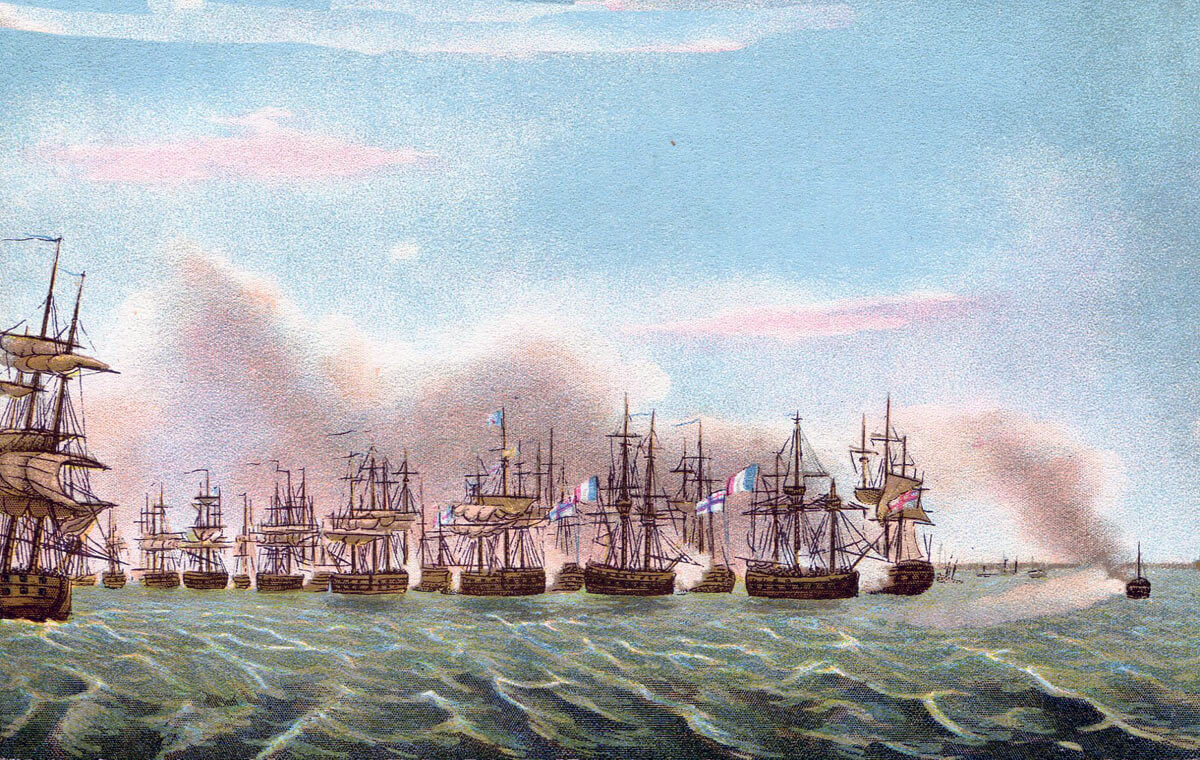

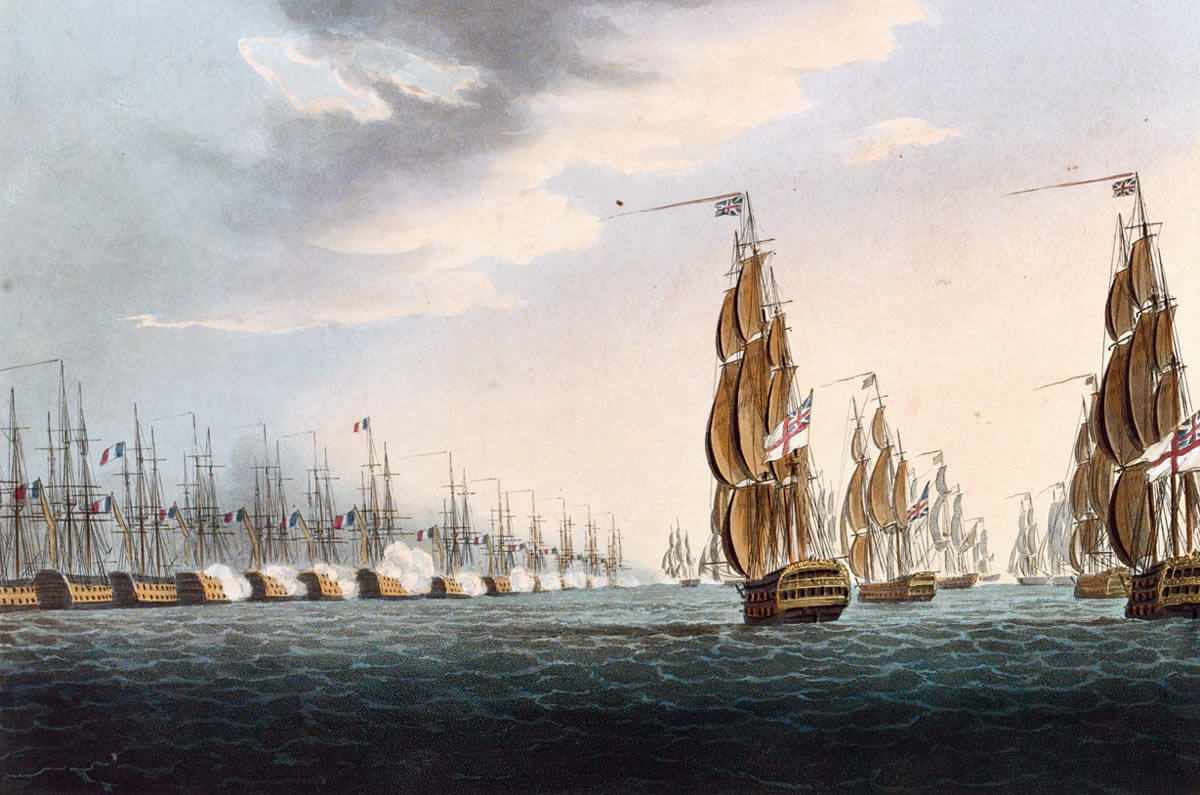

Opening of the Battle of the Nile on 1st August 1798 in the Napoleonic Wars: picture by Nicholas Pocock

Warships carried their main armament in broadside batteries along the sides. Ships were classified according to the number of guns carried, or the number of decks carrying batteries. The size of gun on the line of battle ships was up to 24 pounder, firing heavy iron balls or chain and link shot designed to wreck rigging. Nile was a close fleet action. Ships sailed up to the enemy and in many instances anchored, delivering broadsides at a range of a few yards.

Ships manoeuvred to deliver broadsides in the most destructive manner; the greatest effect being achieved by firing into an enemy’s stern or bow, so that the shot travelled the length of the ship wreaking havoc and destruction. During the Battle of the Nile, HMS Leander and Alexander positioned themselves to ‘rake’ the French Flagship L’Orient from its bow and stern quarters. The first broadside, loaded before action began, was always the most effective. To achieve maximum effect, the British ships held their fire until alongside the French ships, advancing in an ominous silence under the fire of the French Fleet and the shore batteries on Aboukir Island.

Opening of the Battle of the Nile on 1st August 1798 in the Napoleonic Wars: picture by Thomas Whitcombe

Ships carried a variety of smaller weapons on the top deck and in the rigging, from swivel guns firing grape shot or canister (bags of musket balls) to hand held muskets and pistols, each crew seeking to annihilate the enemy officers and sailors on deck.

Wounds in Eighteenth Century naval fighting were terrible. Cannon balls ripped off limbs or, striking wooden decks and bulwarks or guns and metalwork, drove splinter fragments across the ship causing horrific wounds. Falling masts and rigging inflicted severe crush injuries. Sailors stationed aloft fell into the sea from collapsing masts and rigging to be drowned. Heavy losses were caused when a ship finally sank. Only 70 men survived the destruction of the French Flagship L’Orient, from a crew of 500 or more.

Ships’ crews of all nations were tough. The British, with continual blockade service against France and Spain, were particularly well drilled. British gun crews fired three broadsides or more, to every two fired by the French. The French Navy still suffered from the loss of expert naval officers, executed or exiled following the French Revolution of 1789.

French Flagship L’Orient explodes at the Battle of the Nile on 1st August 1798 in the Napoleonic Wars: picture by Robert Dodd

British captains were responsible for recruiting their ship’s crew. Men were taken wherever they could be found, largely by the press gang. All nationalities served on British ships, including French and Spanish. Loyalty for a crew lay primarily with their ship. Once the heat of battle subsided there was little animosity against an enemy. Great efforts were made by British crews to rescue the sailors of foundering French ships. After the Battle of the Nile, some 200 sailors from the French crews were mustered into HM ships.

Account of the Battle of the Nile:

In January 1798, French land forces and a substantial fleet gathered in the French Mediterranean port of Toulon. It was apparent to the British government of William Pitt that General Napoleon Bonaparte intended to invade some part of the Mediterranean, but it was not clear where.

Admiral Lord St Vincent commanded the British Fleet at Gibraltar, from where he directed the blockade of the Spanish Fleet in Cadiz and the deployment of British naval units in the Mediterranean.

HMS Majestic at the Battle of the Nile on 1st August 1798 in the Napoleonic Wars: picture by Charles Edward Dixon

In February 1798, Rear Admiral Sir Horatio Nelson arrived at Gibraltar to act as St Vincent’s deputy and to command operations against Napoleon’s expeditionary force in the Mediterranean. The appointment of such a junior rear admiral caused outrage among more senior naval officers of the same rank.

On 9th May 1798, Nelson sailed from Gibraltar, in his flagship HMS Vanguard, with a small squadron of His Majesty’s Ships Alexander and Orion, four frigates and a sloop, under orders to discover where Napoleon’s fleet and army were bound.

On 20th May 1798, a powerful storm struck Nelson’s squadron, completely dismasting Vanguard, the flagship only being saved by the resource and courage of Captain Bell’s HMS Alexander in taking Vanguard in tow. The squadron was dispersed, the frigates returning to Gibraltar. Vanguard refitted at a Sicilian port in an astonishingly short period of four days.

French Flagship L’Orient explodes at the Battle of the Nile on 1st August 1798 in the Napoleonic Wars: picture by John Thomas Serres

While Nelson was storm bound, the French expedition unexpectedly sailed from Toulon heading south east, provoking a frenzied search by the British.

By Nelson’s assessment, which proved correct, Napoleon intended to take Malta and then invade the Turkish Khediveate of Egypt, providing support to Tipoo Sultan in his fight with the British in India and restoring French influence in that sub-continent. The government in London and the East India Company panicked at the prospect.

French Flagship L’Orient explodes at the Battle of the Nile on 1st August 1798 in the Napoleonic Wars

Refitting in the Sicilian port of St Pietro, Nelson received substantial reinforcements from Lord St Vincent. St Vincent dispatched the reinforcing ships from Gibraltar immediately on the arrival of a powerful squadron from England, the one squadron sailing as the other was signalled. This reinforcement brought Nelson’s fleet to thirteen 74 gun ships of the line. Nelson’s main deficiency was in frigates; the small fast ships of his squadron failing to track him down in time to sail for Egypt.

Burial of a naval officer at sea: Battle of the Nile on 1st August 1798 in the Napoleonic Wars: picture by Eugène Isabey

Many ships plied the Mediterranean, and Nelson had to make do with the information he could glean at random from these passing vessels. He learnt that Napoleon had taken Malta but immediately sailed on 16th June 1798 for the East.

Nelson’s fleet set sail for Egypt where the British searched in vain for signs of the French ships. Nelson returned to Sicily, increasingly concerned at his inability to find Napoleon and the effect on his reputation in England.

On 28th July 1798 Captain Troubridge obtained further confirmation that the French Fleet had gone east from a passing merchantman.

Nelson again sailed for the Egyptian coast, reaching Alexandria on 1st August 1798, to find, whereas on his earlier visit the port had been empty, Alexandria was now filled with French transport vessels. The British Fleet continued along the coast until dusk, at around 6pm, when the signal was flown ‘Enemy in sight.’ The search for the French Fleet was over and Nelson’s ships cleared for action.

French Flagship L’Orient on fire at the Battle of the Nile on 1st August 1798 in the Napoleonic Wars: picture by John Thomas Serres

The French Fleet of Admiral Brueys was unprepared for battle. The journey from France, carrying Napoleon’s army, had left the French ships short of water and supplies.

The two hundred French transport vessels had crowded into the port of Alexandria, leaving no room for the ships of war and forcing Brueys to take his fleet to the east of Alexandria, into the Bay of Aboukir, a long north to south crescent shore, shoaling gently. The French ships anchored in a line as near to the shoal edge as possible to prevent the British, if they should appear, from attacking on the landward station.

Brueys had arrayed his fleet in a line, with the 120 gun L’Orient in the centre, and the other more powerful ships at the southern end of the line.

A careful disposition would have placed the French ships close together, but this was not done and the attacking British were enabled to sail through the French line, firing into the vulnerable bows and sterns of the French ships.

French Flagship L’Orient explodes at the Battle of the Nile on 1st August 1798 in the Napoleonic Wars

The French army occupied nearby Aboukir Island, building batteries to provide their navy with additional protection. A substantial part of the French crews was ashore, digging wells to provide water for their fleet.

It is said that shortage of provisions prevented Brueys’ frigates from cruising off shore to provide warning of the British approach. This hardly seems an adequate excuse.

In every way, the French Fleet was caught napping and Nelson was exactly the commander to take full advantage of the French lack of care.

French Flagship L’Orient explodes at the Battle of the Nile on 1st August 1798 in the Napoleonic Wars: picture by Thomas Luny

The French ships saw the British Fleet as it sailed around the point into Aboukir Bay. One senior French officer urged that the fleet should sail immediately and attempt to meet the attack in the open sea, but Brueys declined to move, his immediate expectation being that Nelson would not attack so late in the day; a vain hope.

It had been Nelson’s practice during the months spent searching the Mediterranean for Napoleon’s Fleet, to assemble his captains and discuss with them plans for any eventuality that might arise, the emphasis being on aggression and immediate attack. There was consequently no need for instructions to his captains; all knew what they should do.

Under a heavy but ineffectual barrage from the French batteries on Aboukir Island, and more effective broadsides from the French ships, the British line, with the wind behind it, rushed down on the French Fleet.

The French brig, Alerte, attempted to lure the British men of war into the shoals, but was ignored by the leading British ships, Goliath and Zealous, racing each other to be the first ship into battle. The action began at about 6.30pm, as the sun set.

HMS Alexander as a prison hulk in the years after the Napoleonic Wars: Battle of the Nile on 1st August 1798 in the Napoleonic Wars

Brueys’ dispositions were immediately set at naught, the two British ships heading straight for the landward side of the French line, Foley’s Goliath anchoring alongside the second French ship, Conquerant, and opening fire, Zealous attacking the lead French ship, Guerrier.

A devastating feature of the French lack of preparation immediately became apparent. The French ships took considerable time to bring their landward batteries into action. The French captains had taken the opportunity of being at anchor to conduct a refit and the landward guns were without tackle and piled with stores and equipment from elsewhere in the ships.

Within twelve minutes of the start of the battle, Guerrier was totally disabled.

The next British ship into action, Orion, again sailing on the landward side, fired into Guerrier, continued down the French line, sinking the frigate Serieuse, before attacking the Franklin and Peuple Souverain simultaneously.

Audacious fired into Guerrier and Conquerant and then engaged Peuple Souverain. Theseus also fired into the wretched Guerrier, before anchoring by Spartiate, to exchange broadside after broadside.

French Flagship L’Orient explodes at the Battle of the Nile on 1st August 1798 in the Napoleonic Wars: picture by Philip James de Loutherbourg

Nelson’s Flagship Vanguard was the first British ship to take the seaward side of the French line, attacking Spartiate and taking a heavy fire from Spartiate and the fourth French ship, Aquilon. Within minutes all the gun crews in the forward batteries on Vanguard were dead or wounded.

Louis’ Minotaur anchored ahead of Aquilon and diverted her fire from Vanguard, giving the flagship the respite she urgently needed.

The relentless aggression of the British captains was vividly illustrated by the conduct of HMS Bellerophon. Darby took his ship past Vanguard and Minotaur to attack the French Flagship, L’Orient, the largest ship in the battle. Within the hour, Bellerophon had taken substantial casualties and drifted away, dismasted and helpless, all its officers dead or wounded.

HMS Defence and Majestic entered the line on the seaward side, Defence attacking the Franklin, sixth in the French line, and Majestic receiving a heavy fire from L’Orient before attacking Heureux and Tonnant.

HMS Culloden grounds on the shoal during the British attack at the Battle of the Nile on 1st August 1798 in the Napoleonic Wars: picture by William Anderson

Four British ships, Culloden, Alexander, Swiftsure and Leander, lying to the rear of the main fleet, raced to join the battle. Culloden, leading, grounded in the shoals. Alexander and Swiftsure left Leander and the brig Mutine to assist Culloden and hurried on, both ships attacking L’Orient; Swiftsure firing into her bow quarter, Alexander raking her stern quarter.

Leander, finally leaving the immovable Culloden, took position between Franklin and L’Orient, firing into both.

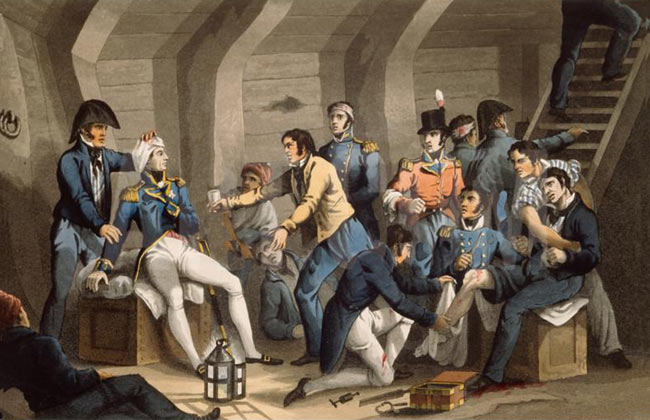

On Vanguard, Nelson was struck on the head by a piece of langridge shot, used to cut rigging, and taken below. When finally seen by the surgeon, the wound was pronounced superficial.

Nelson in Vanguard’s cockpit having his wounds dressed during the Battle of the Nile on 1st August 1798 in the Napoleonic Wars: picture by William Heath

At around 9pm, L’Orient caught fire. Brueys had been wounded three times, the final injury proving fatal. Anchored and with little capacity to move, the French Flagship, already heavily damaged by the intrepid Bellerophon, was under fire from Alexander, Swiftsure and Leander, all firing from quarters that made reply difficult. The final devastating aspect of the French lack of foresight was about to play its part.

Before the battle the crew of L’Orient had been repainting their ship, fresh paint covering the hull. Tubs of unused paint and highly flammable turpentine were positioned around the deck and caught fire in the battle. Once the fire started, the British ships concentrated their shot on the burning area, preventing effective firefighting. Quickly the prodigious conflagration on L’Orient lit up the whole bay. It became clear that the French Flagship was doomed, its crew leaping into the sea, the British ships pulling away and dousing their woodwork and rigging with seawater. Nelson, recovering from his wound below, was called onto Vanguard’s deck.

At 10pm L’Orient exploded. The sound was heard by French troops miles inland and crews of other men of war thought their own ships had blown up.

Nelson called on deck after having his wounds dressed to watch L’Orient burn: Battle of the Nile on 1st August 1798 in the Napoleonic Wars: picture by Daniel Orme

Firing ceased, the deathly pause in the battle plunging the bay into darkness. After a period of stunned silence, the sea and surrounding ships were pelted by falling body parts, timber and debris from the destroyed French Flagship. It was some minutes before the gun crews recovered from the shock of the explosion and the battle resumed.

Desperate efforts were made by the French and British ships to recover the survivors, Lieutenant Galway taking off Vanguard’s long boat. But only around seventy of L’Orient’s crew survived the explosion, many killed in the sea by the blast.

French Flagship L’Orient explodes at the Battle of the Nile on 1st August 1798 in the Napoleonic Wars: picture by Mather Brown

French resistance continued through the night. At dawn Guillaume Tell and Genereux cut their cables and headed for the open sea under Admiral Villeneuve, accompanied by the frigates Diane and Justice. HMS Zealous attempted a pursuit but was soon recalled.

Morning after the Battle of the Nile on 1st August 1798 in the Napoleonic Wars: picture by Robert Dodd

The firing in the bay finally ended at 3pm on 2nd August 1798. The French Fleet had been completely overwhelmed. Of its 13 ships of the line and 4 frigates, 1 ship had sunk, 2 ships were burnt and 9 ships captured by the British.

After the Battle of the Nile, HMS Swiftsure put a landing party into the Aboukir fort and destroyed or removed all the guns.

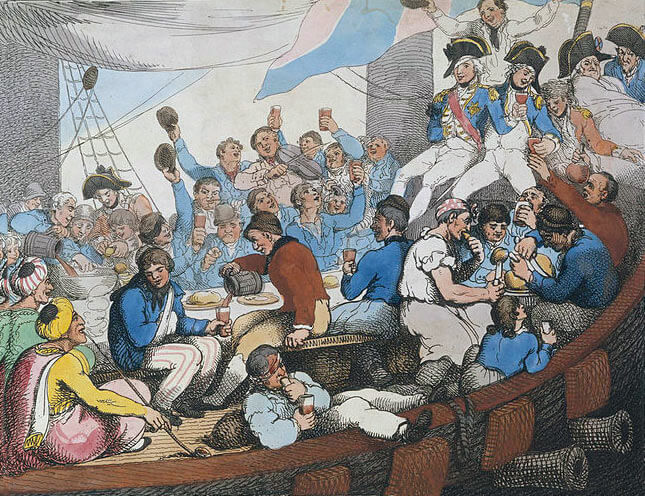

Cartoon of celebrations on HMS Vanguard after the Battle of the Nile on 1st August 1798 in the Napoleonic Wars

Casualties at the Battle of the Nile:

British casualties were 895 including the death of Captain Westcott and Nelson wounded (although he refused to include himself in the official return of wounded).

French casualties were 5,225 dead and 3,105 captured, including wounded.

The French admiral, Brueys, died on the quarterdeck of L’Orient before it exploded. Commodore Casabianca, the captain of L’Orient, died in the explosion with his 10-year-old son.

The wounded Nelson wearing his gold Davison Medal after the Battle of the Nile on 1st August 1798 in the Napoleonic Wars

Follow-up to the Battle of the Nile:

The immediate result of the battle was the collapse of Napoleon’s invasion of Egypt and the lifting of any threat to Britain’s hold on India. Napoleon abandoned his army to its fate and returned to France.

Nelson’s missing frigates arrived a few days after the battle. Nelson is quoted as saying ‘If I were to die today you will find engraved on my heart ‘lack of frigates.’

The battle secured Nelson’s European reputation as a sea commander.

Medals for the Battle of the Nile:

The Naval General Service Medal 1848 was issued to all those serving in the Royal Navy in specified actions during the period 1793 to 1840 and applied for the medal. The medal was only issued to those entitled to one of the 231 clasps.

The Battle of the Nile was such a clasp for the medal.

Naval General Service Medal 1848 with clasp for the Battle of the Nile on 1st August 1798 in the Napoleonic Wars

Medals were also struck privately to commemorate the Battle of the Nile.

Alexander Davison was appointed agent for the considerable number of prizes taken, both men of war and transport vessels. Davison awarded medals for the battle, gold for captains, silver for officers, gilt metal for warrant officers and metal for sailors; at a cost to him of £2,000.

Anecdotes and traditions from the Battle of the Nile:

- As the British Fleet sailed into action, Nelson ordered 6 British colours to be flown from different parts of Vanguard’s rigging to ensure that there was never a time when British colours were not shown. However much of the rigging was brought down by hostile fire.

- L’Orient was carrying a considerable quantity of valuables, including the treasure of the Knights of St John, looted by Napoleon from his capture of Malta. Everything was lost.

- Following the battle, Nelson ordered the British ships to hold services of thanksgiving. The captured atheistic French revolutionary officers are said to have been struck by the devotion shown by the British crews at these services and by their silent discipline.

- All the first lieutenants of the British ships engaged in the Battle of the Nile were promoted to captain by order of the Admiralty.

- It took a month for reliable news of the Battle of the Nile to reach Britain. Initial reports suggested that the French had won.

- Nelson was showered with presents: The Turkish Sultan gave him a ‘Pelisse of Sables’ and a diamond aigrette from his own turban. He also gave 2,000 sequins to be distributed among the British wounded. Nelson was made a baron and awarded a pension of £2,000 per annum. Gifts of money, swords and other items came from the Czar of Russia, the King of Sicily, the City of London and the East Indian Company.

- The poem Casabianca, beginning ‘The boy stood on the burning deck whence all but he had fled’, was written by Felicia Hemans in commemoration of the death of the son of the captain of the L’Orient, killed when the French flagship exploded.

- Two of the French ships captured at the Battle of the Nile, Spartiate and Tonnant, fought in the British line of battle at the Battle of Trafalgar.

- Nelson was obsessed with the idea of dying at the moment of victory. When wounded on the quarterdeck of Vanguard, he thought he had suffered a fatal injury. Taken below, Nelson refused treatment before the sailors already in the cockpit, insisting on waiting his turn. Finally, the surgeon pronounced the wound superficial to ringing cheers of relief from Vanguard’s crew. Nelson returned to the quarterdeck to see L’Orient destroyed, an apocalyptic moment.

- After the Battle of the Nile, Swiftsure recovered a section of L’Orient’s mainmast. The ship’s carpenter made it into a coffin which Captain Hallowell presented to Nelson. Nelson kept the coffin standing in his cabin.

- Nelson’s captains at the Nile formed ‘the Egyptian Club’ to meet and commemorate the battle. Among their first actions were to present a sword to Nelson and commission his portrait.

- At the instigation, it is said, of Lady Hamilton and Captain Hardy, the Marquess of Queensbury laid out a plantation of trees on his estate near Stonehenge in Wiltshire in the formation of the fleets at the Battle of the Nile, known as the ‘Nile Clumps’.

- The explosion of the French Flagship L’Orient at 10pm on 1st August 1798 at the height of the Battle of the Nile is one of the most painted subjects in naval history. Several of the best examples appear on this site.

- HMS Bellerophon, the British ship that caused so much damage to L’Orient in the opening part of the Battle of the Nile, was dismasted by L’Orient’s fire. Bellerophon was known to her crew as ‘Billy Ruffian’ and was the ship that, in 1815, took the Emperor Napoleon on board on his surrender after the Battle of Waterloo. Bellerophon ended her career as a convict hulk in Portsmouth Harbour.

References for the Battle of the Nile:

The Royal Navy, a History by Sir W. Laird Clowes

Life of Nelson by Robert Southey

Nelson by Carola Oman

British Battles on Land and Sea edited by Sir Evelyn Wood

British Battles by Grant

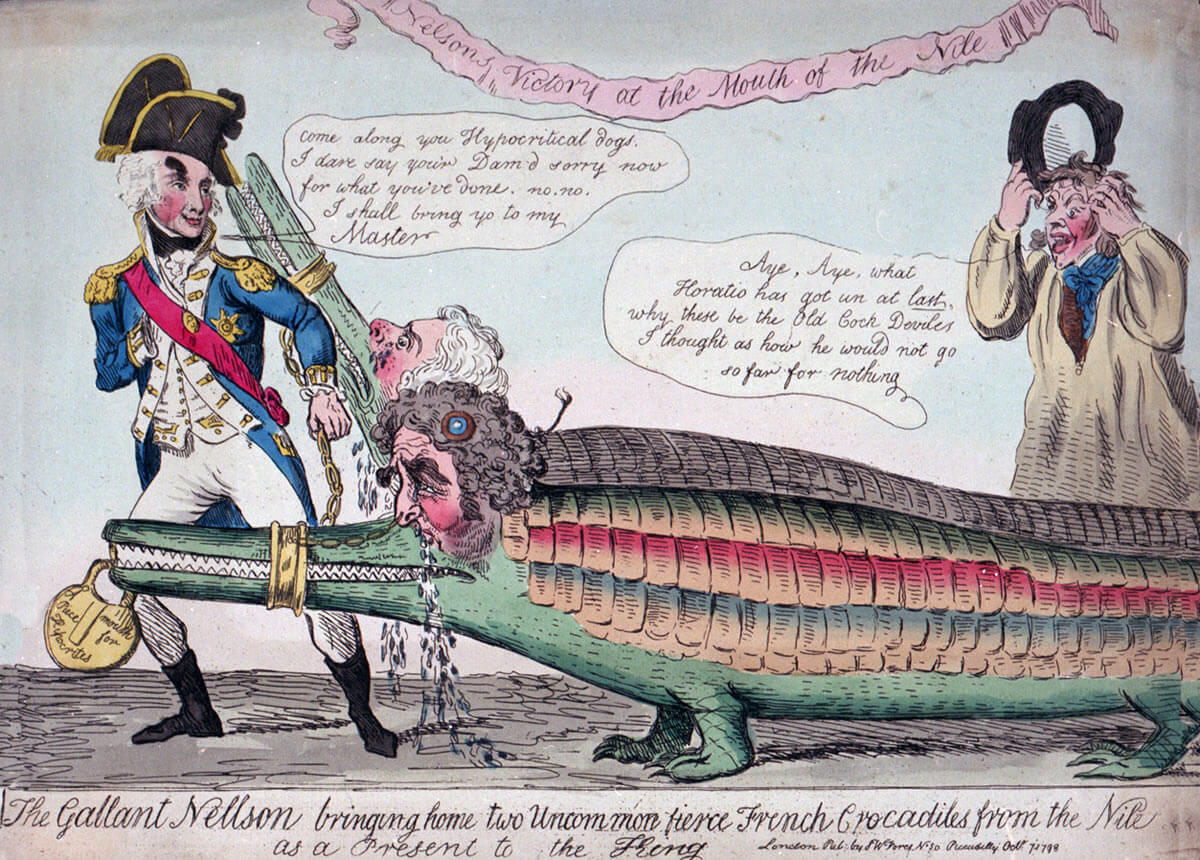

Gilray cartoon showing Nelson dragging the French crocodiles: Battle of the Nile on 1st August 1798 in the Napoleonic Wars

The previous battle in the Napoleonic Wars is the Battle of Cape St Vincent

The next battle of the Napoleonic Wars is the Battle of Alexandria