General Stuart’s victory over the French army of General Reynier in Southern Italy on 4th July 1806 during the Napoleonic Wars

The previous battle in the Napoleonic Wars is the Battle of Trafalgar

The next battle in the Napoleonic Warsis the Battle of Quatre Bras

Battle: Maida (or Santa Euphemia)

War: Napoleonic Wars

Date of the Battle of Maida: 4th July 1806

Place of the Battle of Maida: in Calabria in Southern Italy

Combatants at the Battle of Maida: British against the French.

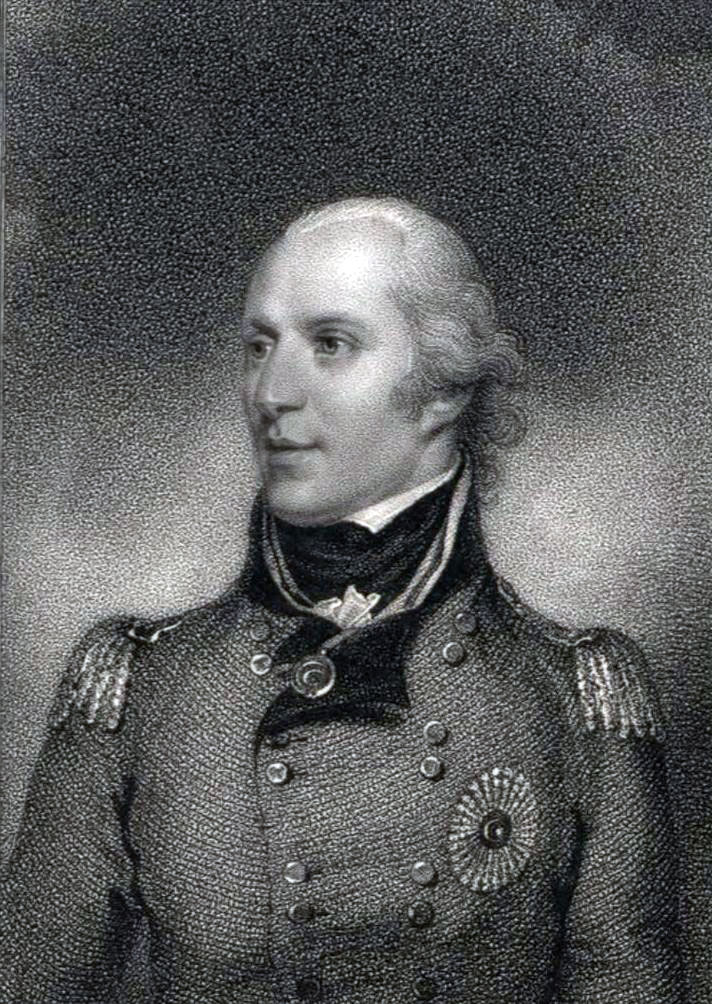

Commanders at the Battle of Maida: Major General Sir John Stuart against Général Jean Louis Ebénézer Reynier

Size of the armies at the Battle of Maida: The British force numbered 5,200 infantry with 11 guns. The French force numbered 6,000 French, including some 1,500 cavalry and 6 guns.

Winner of the Battle of Maida:

The British army of General Stuart.

British Order of Battle:

Commander: Major General Sir John Stuart

Advanced Corps or Light Infantry Brigade (Colonel Sir James Kempt): light companies of 20th, 1st/27th, 1st /35th, 1/58th, 1st/61st, 1st/81st and De Watteville’s Swiss Regiment, ‘Flankers’ of 1st/35th and 2 companies of Corsican Rangers.

1st Brigade (Brigadier General Sir Galbraith Cole): 1st/27th (less flank cos) with grenadier companies of 20th, 1st/27th, 1st/36th, 1st/58th, 1st/81st and De Watteville’s and three 4 pounder guns.

2nd Brigade (Brigadier General Sir Wroth Acland): 2nd/78th Highlanders, 1st/81st (less flank cos) and three 4 pounder guns.

3rd Brigade (Colonel John Oswald): 1st/58th and De Watteville’s (each less flank cos) and three 4 pounder guns.

Detached under Colonel Robert Ross: 20th Regiment (less flank companies).

French Order of Battle:

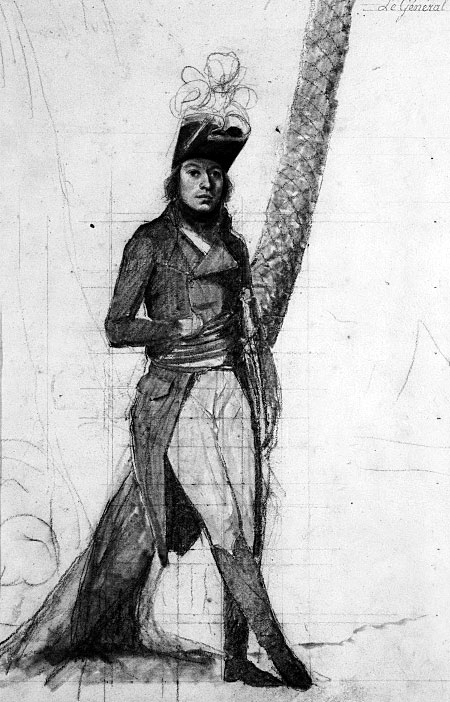

Commander: General Reynier

Brigade of General Compère: 1st/1st Light Regiment, 2nd/1st Light Regiment and 1st/42nd Line Regiment

Brigade of General Digonet: 1st/23rd Light Regiment and 2nd/23rd Light Regiment.

Brigade of Colonel Peyri: 1st/1st Italo-Polish Regiment, 2nd/1st Italo-Polish Regiment and 4th/1st Regiment of Swiss Infantry.

Cavalry: 1st/9th Chasseurs à Cheval, 2nd /9th Chasseurs à Cheval, 3rd/9th Chasseurs à Cheval and 4th/9th Chasseurs à Cheval.

Guns: battery of horse artillery (6 guns).

Background to the Battle of Maida:

In 1805, the British Government despatched an army to Malta with the intention that it should land in Southern Italy with a Russian force brought in British ships from the Black Sea and from Corfu and assist in the defence of the Kingdom of Sicily and Naples, with its capital city of Naples, against the French armies of the Emperor Napoleon.

The plan finally agreed by Major General Craig, the British army commander and Marshal Lascy, the Russian commander, was for a joint landing at Naples. The landing was carried out.

On 20th October 1805 the Austrian army on the Danube was destroyed at the Battle of Ulm, the commander, Mack, surrendering with his troops to the Emperor Napoleon.

The immediate result of the battle was the departure of the Austrian army under Archduke Charles from Northern Italy to cover Vienna.

Soon after landing in Naples, General Craig received news of Nelson’s victory at the Battle of Trafalgar on 21st October 1805.

On 6th December 1805 the French and Austrians signed an armistice, leaving the Russians and British in Naples to face the French alone.

The elderly king of Naples was intimidated by the Emperor Napoleon into signing an undertaking of neutrality.

Although the Russian Tsar Alexander continued to resist Napoleon in eastern Europe, the Russian commander in Naples, the elderly Lascy, was uncertain as to whether Russia was still at war with the French.

In the meantime, French troops in Italy moved south, Napoleon being intent on driving the Bourbon Royal Family from Naples and taking over the kingdom.

By the end of 1805 news reached the British and Russians in Naples that 30,000 to 35,000 French troops were approaching the border of the Kingdom from the north, against which the Russians could muster 14,000 men, of whom 6,000 were sick and the British 7,000, with only a handful of cavalry (two squadrons of the 20th Light Dragoons).

The Russo-British force was unable to assemble sufficient horses to move their artillery or supplies. The army was consequently incapable of movement over land.

An awkward dispute arose from this situation. The Russians wished to withdraw south into Calabria. Craig intended to comply with his instructions from the British Government to secure Sicily, by moving his troops across to that island, while the Royal Family insisted that Naples be defended.

On 7th January 1806, Lascy received orders from the Tsar to return to Corfu and the Russians prepared for their departure.

On 19th January 1806, Craig, ignoring the complaints of the British envoy to the Court of Naples, Hugh Elliot, crossed the Straits of Messina with his troops and, after a stay in the harbour of Messina at the north-eastern tip of Sicily, on 16th February landed and occupied the town of Messina.

The Royal family of the Kingdom of Sicily and Naples did not approve of the abandonment of Naples and required their army to remain on the mainland, where it met the French in battle, was heavily defeated and dispersed, other than a force of cavalry brought over to Sicily by the Royal Navy.

Following the French victory, Napoleon appointed his elder brother Joseph as the King of Naples in place of King Ferdinand.

In early April 1806, Craig, in poor health, left for England, leaving the command of the British force to Major General Sir John Stuart.

Stuart organised the defence of Sicily against the expected incursion by the French from the mainland of Italy.

The Royal Navy squadron with the duty of providing naval cover for Sicily was commanded by Admiral Sir Sidney Smith.

The sole footing maintained by the Bourbon regime on the mainland was the fortress of Gaeta, situated on the coast to the north of Naples, with a garrison commanded by the elderly but resolute Prince of Hesse-Philipstadt.

Marshal Massena attempted to blockade the Fortress of Gaeta, but it was open to the sea and Smith, in late April 1806, re-supplied the fortress and left ships to support a sortie by the garrison, successfully carried out on 15th May 1806.

After taking Capri, Smith returned to Sicily, where he and Stewart planned a re-invasion of Calabria on the Italian mainland.

The plan was founded on a misconception as to the size of Joseph Buonaparte’s French army on the mainland, the British commanders assuming the French army to number 30,000 men, when the number was 50,000, of which 10,000 were in Calabria under Generals Verdier and Reynier.

Stuart’s expectation was that a British landing on the Calabrian coast would lead to a widening of the Calabrian insurrection against the French, with Massena forced to abandon his blockade of the Gaeta Fortress.

Smith was in Palermo at the Royal Court and failed to keep in contact with Stuart, waiting in Messina to begin the operation against the mainland.

Stuart wrote a final letter stating that he did not propose to delay any longer. Smith replied that he was about to sail to resupply the garrison in the Fortress of Gaeta.

Stuart did not wait for a reply to his letter before assembling his troops and, on 26th June 1806, leaving for the mainland, escorted by HMS Apollo and two other warships.

Stuart’s force comprised seven infantry battalions and artillery, numbering 5,500 men, organised in an advanced corps and three brigades.

Two of Stuart’s battalions were made up from the flank companies of his regiments (light and grenadier companies).

Two of Stuart’s battalions, the 2nd/78th Highlanders and 81st Regiments had been recently raised and comprised inexperienced soldiers.

The only cavalry were 16 men from the 20th Light Dragoons, acting as orderlies.

Stuart’s brigadiers were Cole, Kempt, Oswald and Ross. Fortescue describes these officers as ‘all men who made their mark later in the Peninsula’.

The fleet reached its destination, the Bay of Santa Euphemia, on 30th June 1806, Colonel Ross and the 20th Regiment diverting to make feint attacks on Reggio and Scilla.

Stuart’s army disembarked on the beach in Santa Euphemia Bay at dawn on 1st July 1806.

No French troops opposed the landing and the first division of British troops ashore, commanded by Colonel Oswald, advanced the mile inland to the village of Santa Euphemia.

Oswald’s party came under fire and his skirmishers from the Corsican Rangers fell back on the main party.

The second division of British troops was now advancing from the beach and Oswald felt able to counter-attack the French, assaulting each flank and routing them, inflicting losses of 10 officers and 80 men killed or captured.

The French troops turned out to be three companies of Poles stationed in the village of Monteleone.

Oswald advanced and took the village of Santa Euphemia, while the rest of the army disembarked and the engineers prepared a breastwork across the beach, based on an ancient tower, to secure the beach in case it proved necessary to re-embark the army in a hurry.

A letter arrived from Admiral Sir Sidney Smith saying that his fleet was lying off Santa Euphemia Bay, after putting supplies into the Fort of Gaeta.

Stuart replied informing Admiral Smith that he was attempting to bring about a general insurrection against the French by the Calabrian peasantry by assuring them of extensive assistance from the British Government. This action was well beyond Stuart’s instruction and in due course called down heavy censure on him from London.

On the night of 1st July 1806, a heavy swell rose in the Bay of Santa Euphemia, hampering the landing of stores and causing Stuart to delay his advance inland.

In the meantime, on hearing of the departure of Stuart’s fleet from Messina, the French commander, General Reynier, had left Reggio for the eighty-mile march to Maida, collecting additional troops on the way, giving him a superiority in numbers over the British.

Reynier arrived at Maida on the night of 2nd/3rd July 1806, with 6 French battalions (4,123 men), 1 Swiss battalion (630 men), 2 Polish battalions (937 men), 328 cavalrymen and 373 artillery and engineers, making a total force of 6,391 men.

General Compère commanded a brigade of four battalions of the 1st Light and 42nd Line. General Digonet commanded two battalions of the 23rd Light and three battalions of Poles and Swiss infantry.

On the morning of 3rd July 1806, Stuart was informed that the French army was encamped on the banks of the River Lamato below the village of Maida.

In the afternoon of 3rd July 1806, Stuart and his staff carried out a reconnaissance of the French position and decided that the attack had to be carried out to the left of the French camp, covered as it was by the river at the front.

Curiously, Reynier with his staff carried out a reconnaissance of the British army at much the same time, the two parties passing each other in the woods, unaware of the other’s presence.

Estimates received by Stuart as to the number of French troops opposing him varied widely from 3,000 to 6,000.

Stuart chose to operate on the basis of the smaller number and resolved to move against Reynier’s camp the next day.

A strong party with guns was left in the entrenchments now built on the beach.

The Battle of Maida:

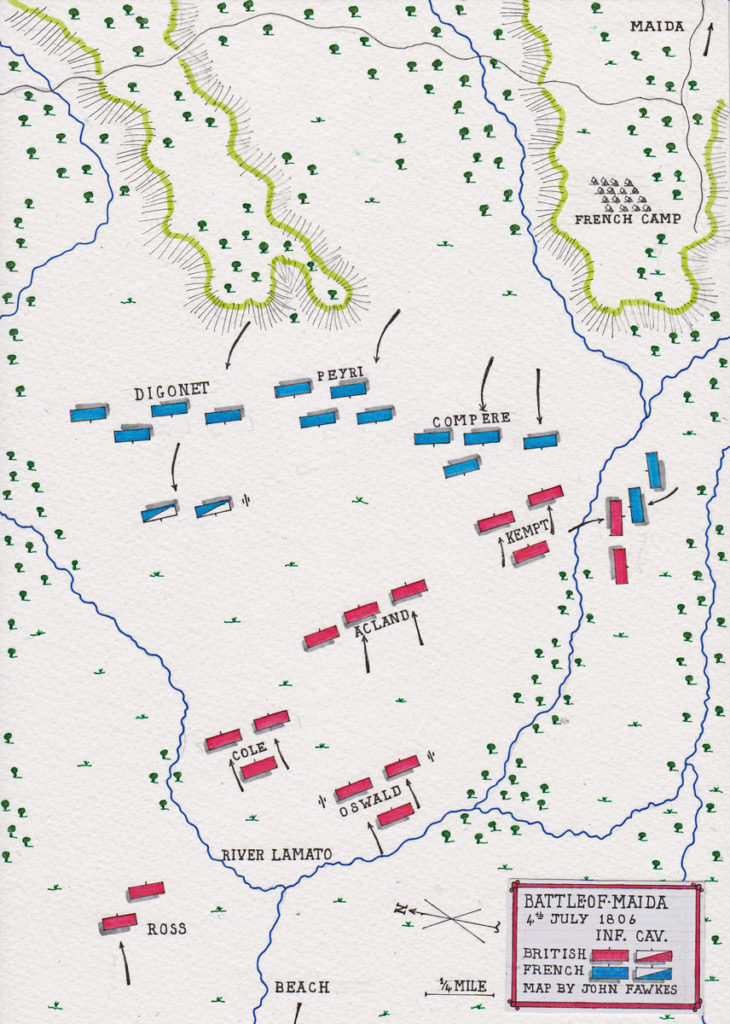

At daylight on 4th July 1806, Stuart’s force of 4,300 men with 3 field guns and 8 mountain guns marched out to attack the French.

The army marched south along the beach to the mouth of the River Lamato, where it turned inland.

The four British brigades marched in two parallel columns, Kempt’s and Cole’s forming the left column and Acland’s and Oswald’s the right column.

Two mule born mountain guns were with each brigade with three field guns accompanying the right column.

HMS Apollo and two small ships sailed alongside the marching troops to guard against any French naval threat.

The advance of the British troops was shadowed by the French cavalry further inland.

On reaching the mouth of the River Lamato, at 8.45am, the British columns wheeled to the left and began their advance inland parallel to the river bank.

The French cavalry fell back and in the French infantry could be seen marching out of their camp and crossing the arm of the River Lamato to confront the British.

Reynier was confident that his 6,000 experienced troops would be sufficient to beat the British.

Fortescue comments that Reynier had clearly forgotten the French experience in Egypt in 1801 at the Battle of Alexandria.

The British brigades, on leaving the beach, entered an area of marsh and woods, from which they emerged in an oblique line, Kempt in front on the right, marching along the line of thicket on the river bank, with Acland’s and Cole’s Brigades to his left, in echelon.

Oswald’s Brigade and the three field guns followed as a reserve in the centre.

The French cavalry and horse artillery moved about in front of the British advance, exchanging gunfire with the British artillery and obscuring the positions of the French infantry.

The sun was hot and the dry conditions generated clouds of dust.

Kempt sent the Corsican Rangers, supported by the Light Company of the 20th Regiment, across the shallow River Lamato, to clear French skirmishers from the scrub on the far bank.

Firing and a charge by the two French companies of skirmishers through the undergrowth drove the Corsican Rangers back across the river.

The light company of the 20th Regiment stood firm and, on being supported by the 35th Regiment, drove the French light infantry back.

The Corsican Rangers returned to the fight, enabling the companies of the 35th Regiment to resume their position on the right of Kempt’s Brigade.

The French cavalry now galloped off to the British left, leaving the ground clear for the attack by the French infantry.

It immediately became clear that the rapidly advancing French battalions were considerably superior in numbers to the British.

Reynier intended to pierce the British line, leaving a significant portion of the British force unable to escape the battlefield and forced to surrender.

Reynier’s army advanced in three columns: on the left Compère’s Brigade of the 1st Light Infantry and the 42nd of the Line: in the centre was the newly formed Peyri’s Brigade of two Polish battalions and one Swiss: on the right Digonet’s Brigade of the 23rd Light, the cavalry and guns.

The French numbers were: 2,800 in Compère’s Brigade, 1,500 in Peyri’s Brigade and 1,250 infantry in Digonet’s Brigade.

The French army crossed the River Lamato to the west of its camp and turned to the south, to advance towards the British. This turn put the French line into a form of echelon similar to the British, so that the first formations to clash were Compère’s and Kempt’s.

The regiments of Compère’s Brigade were in echelon with the 1st Light Infantry in advance and the 42nd of the Line to its right rear.

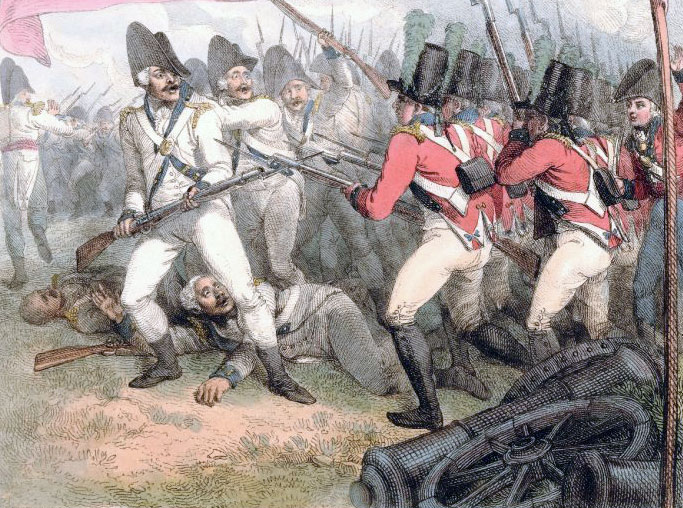

The two battalions of the French 1st Light Infantry advanced in column of companies at a great pace.

The 700 men of Kempt’s Light Companies were formed in two lines and fired their first volley at a range of 115 yards.

The French attempted to return the fire but continued their rapid advance.

The British light infantrymen fired their second volley at 80 yards.

As the French light infantrymen were probably advancing at around 150 paces to the minute it will have taken the British light infantrymen quarter of a minute to reload and fire their second volley.

Compère urged his men to charge with the bayonet.

Kempt called to his men ‘Steady, Light Infantry. Wait for the word. Let them come close.’

At a range of 30 yards, Kempt’s Light Infantry fired their third volley.

This final blow caused Compère’s two battalions to halt and fall back, other than a few men from the left battalion, led by Compère into the British ranks.

Kempt gave the order to charge and the whole of Compère’s Brigade was driven back with considerable loss.

Kempt’s men pursued Compère’s troops through their camp and back along the road to Maida, where Kempt managed to rally his men.

The casualties of the French 1st Light were 900 men, killed, wounded or captured against less than 50 British casualties.

On the right of the French 1st Light Infantry, the French 42nd of the Line advanced on Acland’s Brigade, comprising 2nd/78th Highlanders and the 81st, both recently raised battalions.

Dismayed at the handling of the 1st, the 42nd took two volleys from Acland’s men before turning and fleeing towards Catanzaro, leaving more than a third of their number as casualties.

Acland’s regiments, following them up, came upon the Polish and Swiss battalions.

The two Polish battalions, attacked by the British 81st Regiment, immediately gave way.

The Swiss battalion, on the other hand, probably being mistaken by the 78th as De Watteville’s Swiss Regiment, due to their red coats, was enabled to approach the 78th and deliver a damaging volley.

The 78th began to retreat, but were brought back into the line by Major David Stewart.

After a sharp fight between the 78th and the Swiss, the Swiss retired to the right and reformed on Digonet’s Brigade.

Acland’s Brigade pressed forward but were attacked by the French cavalry.

Forming squares, the 81st and 78th suffered some loss from the fire of the French horse artillery.

Cole’ Brigade on the British left was further behind in the oblique advance, due to the threat from the French cavalry and the need to await the advance of the British guns.

Cole came into action some twenty minutes after Acland’s attack, closely supported by Oswald’s reserve.

Due to the collapse of the French left and centre, Reynier was forced to rely upon Denier’s Brigade as a rear-guard.

Denier’s 23rd Light Infantry stood on the right with the French guns in the centre and the Swiss battalion on the left.

The threat of a charge from the French cavalry kept Cole’s brigade in check.

French skirmishers deployed in the scrub on Cole’s left further harassing his men, who were suffering from the heat and were short of ammunition.

Oswald’s Brigade came up on Cole’s right, extending the line and holding the French in check.

At this point, Colonel Ross, having arrived at the beach and landed his men, brought up the 20th Regiment on Cole’s left, cleared the French skirmishers from the scrub and, continuing his advance, poured volleys into the right flank of Denier’s 23rd Light Infantry.

Reynier withdrew his infantry under the cover provided by the French cavalry and retreated with some haste to Catanzaro.

The British brigade commanders seem to have been left to fight the battle with little direction from Stuart, who now decided that there should be no pursuit of the French, due to the British lack of cavalry.

Kempt’s brigade, well forward and joined by Ross’s 20th Regiment, continued to advance in parallel with the retreating French, until, lacking orders to continue the pursuit, Kempt returned to the main army, leaving the light company of the 20th Regiment under Captain Colborne to continue to follow the French for a time.

Stuart ordered the rest of the British troops to return to the beach, where they were permitted to bathe in the sea.

A staff officer rode onto the beach giving a warning that a French attack was pending. The troops hurried out of the sea and put on their equipment before forming up. There was insufficient time to put on any clothing. It turned out to be a false alarm.

The French had withdrawn and the battle was over.

Casualties at the Battle of Maida:

In the Battle of Maida, the British casualties were 1 officer and 44 soldiers killed, with 11 officers and 271 soldiers wounded.

The French casualties in the battle were, according to Reynier’s report, 1,300 killed, wounded or missing.

The British Quartermaster General reported that more than 500 French bodies were buried on the field and that more than 1,000 wounded and unwounded prisoners were taken.

Fortescue asserts that the true figure for French casualties was probably over 2,000.

Follow-up to the Battle of Maida:

Fortescue states that the action of Maida was an ‘extremely brilliant and creditable little affair’ and could have been exploited by moving the British troops with the naval vessels to relieve the fortress of Gaeta and threaten the French position in Naples which would, Fortescue claims, have forced Reynier to march the French troops in Calabria north to secure the French hold on Naples, leaving the Italian insurrection in the south to take a strong hold on the country.

Battle Honours and Medal for the Battle of Maida:

‘Maida’ was a battle honour for the following British regiments: 20th, 27th, 35th, 58th, 61st, 78th and 81st Regiments.

The Military General Service Medal 1848 was issued to all those serving in the British Army present at specified battles during the period 1793 to 1840, who were still alive in 1847 and applied for the medal. The medal was only issued to those entitled to one or more of the clasps.

The Maida Gold Medal was struck and awarded to the thirteen senior British officers involved in the battle.

‘Maida’ was one of those clasps.

Anecdotes and traditions from the Battle of Maida:

- As the French 1st Light Infantry advanced, Kempt ordered his British light infantrymen to take off their packs and blankets prior to a charge. Onlookers and the French are said to have thought the action of throwing down packs and blankets was a preliminary to running away. All were amazed when the British light infantrymen launched into a precipitate charge, sweeping away their French adversaries.

- The Battle of Maida caused a sensation in Britain. A pub was built in Middlesex, north-west of London and named the ‘Maida’. The pub sign displayed a portrait of General Stuart. In due course as London extended, the area around the pub became ‘Maida Vale’.

- Fortescue describes what he considers to be the frequently repeated sequence of event when French columns unsuccessfully attacked British lines: ‘The fight presents all the familiar features of the later battles in the Peninsula- a reckless dashing of a deep but narrow mass of bayonets against a shallow but broad front of muskets, with the inevitable result that the narrow front could not compete with the broad in development of fire, and that the columns were shattered to pieces in front and flank by bullets before the bayonets could come into play. The consequence which seems invariably to have followed was, psychologically, most curious. The head of the column, though staggering and wavering, still strove gallantly to advance, but the tail turned and ran; and the leading files finding themselves abandoned, broke at once before the charge of the victorious line.’

- While the battle showed the French column to be an inappropriate mechanism for attacking steady disciplined troops in line, Reynier chose to blame the defeat on failings in the French soldiers not the system of attack in column, a criticism taken up by French senior staff.

References for the Battle of Maida:

Fortescue’s History of the British Army Volume V.

British Battles on Land and Sea

The previous battle in the Napoleonic Wars is the Battle of Trafalgar

The next battle in the Napoleonic Warsis the Battle of Quatre Bras