Admiral Lord Nelson’s ‘hardest fought battle’, against the Danish Fleet and the Danish Capital City of Copenhagen on 2nd April 1801

The previous battle of the Napoleonic Wars is the Battle of Alexandria

The next battle of the Napoleonic Wars is the Battle of Trafalgar

Admiral Lord Nelson: Battle of Copenhagen on 2nd April 1801 in the Napoleonic Wars: picture by Lemuel Francis Abbott

War: Napoleonic Wars.

Date of the Battle of Copenhagen: 2nd April 1801.

Place of the Battle of Copenhagen: the coast of Copenhagen, the capital city of Denmark.

Combatants at the Battle of Copenhagen: A British Fleet against the Danish Fleet.

Commanders at the Battle of Copenhagen: Admiral Sir Hyde Parker and Vice Admiral Lord Nelson against the Danish Crown Prince.

Winner of the Battle of Copenhagen: The British Fleet.

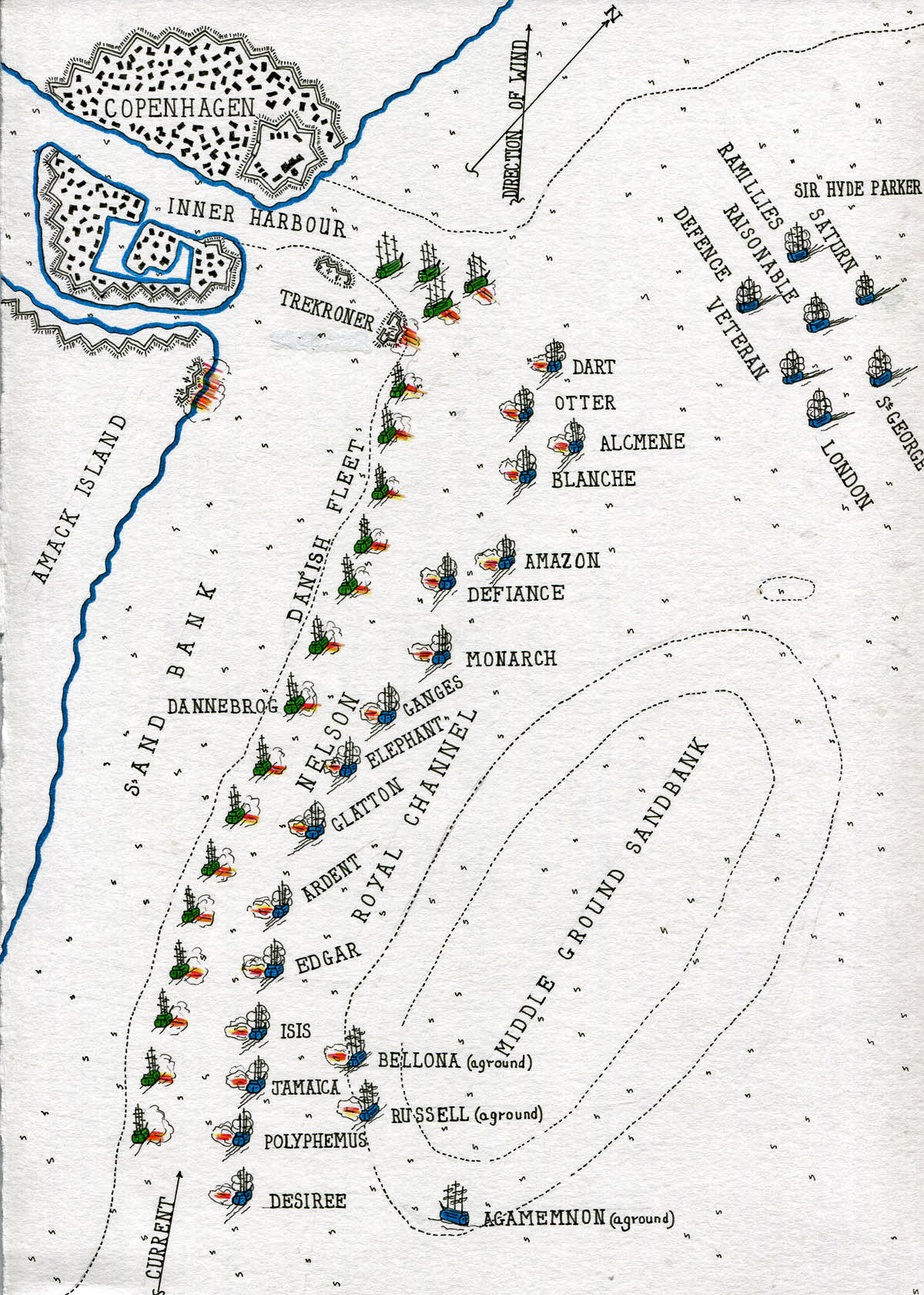

The Fleets at the Battle of Copenhagen:

The British Fleet: Nelson’s Division, His Majesty’s Ships Elephant (Nelson’s Flagship: Captain Foley, 74 guns), Russell (Captain Cumming, 74 guns), Bellona (Captain Thompson, 74 guns), Edgar (Captain Murray, 74 guns), Ganges (Captain Freemantle, 74 guns), Monarch (Captain Moss, 74 guns), Defiance (Rear Admiral Graves’ Flagship: Captain Retalick, 74 guns), Polyphemus (Captain Lawford, 64 guns), Ardent (Captain Bertie, 64 guns), Agamemnon (Captain Fancourt, 64 guns), Glatton (Captain William Bligh, 54 guns), Isis (Captain Walker, 50 guns), Frigates, La Desiree (Captain Inman, 40 guns), Amazon (Captain Riou , 38 guns), Blanche (Captain Hammond, 36 guns), Alcimene (Captain Sutton, 32 guns), Sloops: Arrow (Commander Bolton, 30 guns), Dart (Commander Devonshire, 30 guns), Zephyr (Lieutenant Upton, 14 guns), Otter (Lieutenant McKinlay, 14 guns).

Parker’s Division: His Majesty’s Ships London (Flagship, Captain Domett, 98 guns), St George (Captain Hardy, 98 guns), Warrior (Captain Tyler, 74 guns), Defence (Captain Paulet, 74 guns), Saturn (Captain Lambert, 74 guns), Ramillies (Captain Dixon, 74 guns), Raisonable (Captain Dilkes, 64 guns), Veteran (Captain Dickson, 64 guns).

In addition; the Trekroner Fortress and numerous batteries along the coast.

Ships and Armaments at the Battle of Copenhagen:

Life on a sailing warship of the 18th and 19th Century, particularly the large ships of the line, was crowded and hard. Discipline was enforced with extreme violence, small infractions punished with public lashings. The food, far from good, deteriorated as ships spent time at sea. Drinking water was in short supply and usually brackish. Shortage of citrus fruit and fresh vegetables meant that scurvy quickly set in. The great weight of guns and equipment and the necessity to climb rigging in adverse weather conditions frequently caused serious injury.

Warships carried their main armament in broadside batteries along the sides. Ships were classified according to the number of guns carried, or the number of decks carrying batteries. The size of gun on the line of battle ships was up to 24 pounder, firing heavy iron balls or chain and link shot designed to wreck rigging. The first discharge, loaded before action began, was always the most effective.

HMS Elephant Admiral Lord Nelson’s flagship at the Battle of Copenhagen on 2nd April 1801 in the Napoleonic Wars

Ships manoeuvred to deliver broadsides in the most destructive manner; the greatest effect being achieved by firing into an enemy’s stern or bow, so that the shot travelled the length of the ship, wreaking havoc and destruction.

The Danish ships at the Battle of Copenhagen were moored to the jetties. The British ships anchored alongside the moored Danish Fleet and the firing was broadside to broadside at a range of a few yards.

Ships carried a variety of smaller weapons on the top deck and in the rigging, from swivel guns firing grape shot or canister (bags of musket balls) to hand held muskets and pistols, each crew seeking to annihilate the enemy officers and sailors on deck.

Wounds in Eighteenth Century naval fighting were terrible. Cannon balls ripped off limbs or, striking wooden decks and bulwarks or guns and metalwork, drove splinter fragments across the ship causing horrific wounds. Falling masts and rigging inflicted severe crush injuries. Sailors stationed aloft fell into the sea from collapsing masts and rigging to be drowned. Heavy losses were caused when a ship finally sank.

Ships’ crews of all nations were tough and disciplined. The British, with continual blockade service against France and Spain, were particularly well drilled.

British captains were responsible for recruiting their ship’s crew. Men were taken wherever they could be found, largely by the press gang. All nationalities served on British ships, although several ships permitted Danish crewmen to transfer rather than serve against their own countrymen. Loyalty for a crew lay primarily with their ship. Once the heat of battle subsided there was little animosity against the enemy. Great efforts were made by British crews to rescue the sailors of foundering Danish ships at the end of the Battle of Copenhagen.

Captain Riou who led the attack on the Trekroner Fortress and was killed at the Battle of Copenhagen on 2nd April 1801 in the Napoleonic Wars

Account of the Battle of Copenhagen:

In early 1801, Britain faced a coalition of northern European states, masterminded by France, combined in hostile neutrality against Britain, the Northern Confederation. Those states were Russia, Denmark, Sweden and Prussia. The British Admiralty ordered Admiral Sir Hyde Parker with a British fleet to the Baltic, with Admiral Lord Nelson as his second in command, to break up the confederation.

On 18th March 1801, the British Fleet anchored in the Kattegat, the entrance to the Baltic from the North Sea, and British diplomats set off for Copenhagen.

It was Nelson’s plan that the British Fleet should attack the Russian squadron wintering in the port of Revel, the Russian navy being the strongest and the dominant naval force in the Baltic.

There was a lack of trust between Parker and Nelson; Parker keeping Nelson at arm’s length, while the British diplomats negotiated with the Danes to obtain their withdrawal from the coalition.

The negotiations with the Danes exasperated Nelson, a man of action, who wanted to attack the Danes and destroy their fleet, before moving on to Revel and the Russian ships. Nelson’s flagship HMS St George had been cleared for action for a week.

On 23rd March 1801, Parker called a council of war at which the British diplomats revealed that the Danish Crown Prince and his government, actively hostile to Britain, were not prepared to withdraw Denmark from the coalition and that the defences of Copenhagen were being strengthened.

Nelson urged that the Danish Fleet be attacked without delay, saying: “Let it be by the Sound, by the Belt, or anyhow, only lose not an hour.”

On 26th March 1801, the British Fleet moved towards the Sound, the gateway to the Baltic, and the great Danish fortress of Kronenburg. Preparing for the battle, Nelson moved his flag to the smaller ship Elephant, 74 guns, whose captain, Foley, had led the attack at the Battle of the Nile.

On 30th March 1801, the wind was fair for the British advance on Copenhagen and the British Fleet passed the Sound, keeping to the Swedish side.

Admiral Nelson forcing the Passage of the Sound before the Battle of Copenhagen on 2nd April 1801 in the Napoleonic Wars: picture by Robert Dodd

In the event, the Swedes held their fire, while the Danes at Cronenburg fired without effect, the range being too great. The British Fleet anchored five miles below Copenhagen, allowing the senior officers to reconnoitre the city’s defences in the lugger Skylark. During this reconnaissance, key buoys, removed by the Danes, were replaced by pilots and sailing masters in the British service.

Under the British plan the commander-in-chief, Admiral Sir Hyde Parker, would advance from the north with the largest British ships, thereby forestalling any relieving attack by the Swedish Fleet or a Russian squadron. Nelson would take his division into the channel outside Copenhagen Harbour, and, sailing northwards up the channel, attack the Danish warships moored along the bank, until he reached the largest ships moored by the powerful Danish fortress of Trekroner, at the entrance to Copenhagen Harbour.

Admiral Sir Hyde Parker generously left the planning to Nelson, even offering him two more ships of the line for his squadron than Nelson had requested.

On 1st April 1801, Nelson carried out his final reconnaissance on the frigate Amazon. The captain of Amazon, Captain Riou, impressed him most favourably and Nelson resolved to give him a leading role in the attack.

On the night of 1st April 1801, Nelson drafted his final plans and briefed his officers, while Captain Hardy ventured right up to the Danish ships in a long boat and took soundings; the pilots placing the last of the buoys.

Nelson’s plan was simple: his ships in line ahead would sail into the inner channel, Royal Passage, each ship anchoring in its appointed place and attacking its assigned Danish rival. Captain Riou in HMS Amazon was to lead a squadron of smaller ships and attack the Trekroner Fortress, which was to be stormed by marines and soldiers at a suitable moment, after it had been reduced by bombardment.

At 8am on 2nd April 1801, the assault began, with His Majesty’s Ship Edgar (Captain Murray, 74 guns) leading the division from its anchorage and tacking from the Outer Deep into the Royal Passage. Immediately, disaster struck Nelson’s division as HMS Agamemnon (Captain Fancourt, 64 guns), Nelson’s old ship, unable to weather the turn into the channel, ran aground on the shoal known as the Middle Ground. Polyphemus (Captain Lawford, 64 guns), taking over Agamemnon’s lead role, made the U turn into the Royal Passage and came under heavy fire from the Danish ship Provesteen (Captain Lassen, 56 guns).

The following ships, Isis (Captain Walker, 50 guns), Glatton (Captain William Bligh, 54 guns) and Ardent (Captain Bertie, 64 guns), made the turn and, anchoring, engaged the Danish vessels they had been allocated.

Attempting to pass these ships, Bellona (Captain Thompson, 74 guns) grounded on the Middle Ground shoal, as did the following Russell (Captain Cumming, 74 guns). Stuck fast, these ships fired on the Danes as best they could, but several of the guns on Bellona burst, killing their crews, due to the age or the miscasting of the barrels, or overcharging in an effort to achieve greater range.

Nelson’s British Fleet sails up the Royal Channel to attack the Danish Fleet and the Trekroner Citadel (The three British ships aground to the right are Bellona, Russell and Agamemnon): Battle of Copenhagen on 2nd April 1801 in the Napoleonic Wars: picture by John Thomas Serres

The grounding of Agamemnon, Bellona and Russell caused the Trekroner Fortress to be left unmarked, requiring Riou to carry out the bombardment with his squadron of smaller vessels, the billowing smoke concealing his ships and protecting them initially from excessive damage.

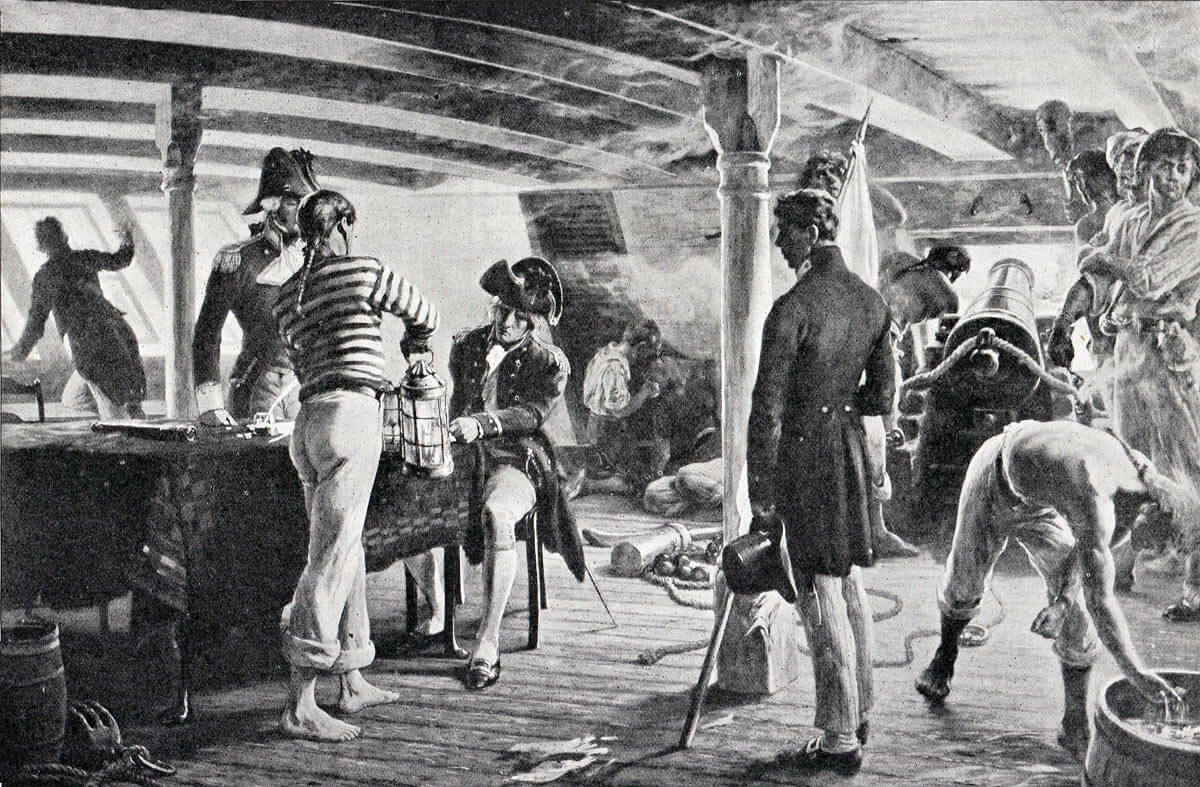

Nelson, in Elephant (Captain Foley, 74 guns), took the anchorage allocated to Bellona, with Ganges (Captain Freemantle, 74 guns) and Monarch (Captain Moss, 74 guns) anchoring immediately in front of Elephant. With the line in place, the battle fell to a slogging gunnery match between the British ships and the Danish ships and batteries, floating and land, which lasted some two hours.

Lieutenant Willemoes of the Royal Danish Navy fights his ship Gerner Radeau during the Battle of Copenhagen on 2nd April 1801 in the Napoleonic Wars: picture by Christian Mølsted

To the north, Admiral Sir Hyde Parker, the British commander-in-chief, witnessed with increasing anxiety the heavy bombardment, as the large ships of the line in his squadron beat slowly down the channel, the wind fair for Nelson but contrary for them. Seeing the intensity of the battle, Parker concluded that he should give Nelson the opportunity to break off the action, and hoisted the signal to disengage, giving the battle its most famed episode.

Admiral Lord Nelson puts the telescope to his blind eye at the Battle of Copenhagen on 2nd April 1801 in the Napoleonic Wars

Nelson’s signal officer, seeing the flagship’s message, queried whether the commander-in-chief’s signal should be repeated to the other ships, to which Nelson directed that only an acknowledgement was to be flown, while signal 16, the order for close action, be maintained.

No ship in Nelson’s division acted on Parker’s signal, except Captain Riou’s squadron, attacking the Trekroner Fortress. Riou, expecting that Nelson would call off the assault, turned his ship to begin the withdrawal. The Danes redoubled their fire, causing significant damage and casualties on Riou’s ships, with one shot cutting down a party of marines and the next killing Riou himself.

Nelson turned to Colonel Stewart, commanding the contingent of soldiers carried in the fleet, and said ‘Do you know what’s shown on board of the commander in chief? Number 39, to leave off action! Leave off action! Now damn me if I do.’ Turning next to his flag captain, Nelson said ‘You know, Foley, I have only one eye. I have a right to be blind sometimes.’ Nelson then raised his telescope to his blind eye and said ‘I really do not see the signal.’

By 2pm on 2nd April 1801, much of the Danish line ceased firing, with ships adrift and on fire, several having surrendered, their captains now on board Elephant.

Captain Thesiger Royal Navy goes ashore with Nelson’s letter to the Danish Crown Prince Frederick at the Battle of Copenhagen on 2nd April 1801 in the Napoleonic Wars: picture by C.A. Lorentzen

Captain Thesiger, a British officer with extensive experience of the Baltic Sea from service in the Russian navy, went ashore with correspondence from Nelson to the Danish Crown Prince, inviting an armistice. During the negotiations, only the batteries on Amag Island, at the southern end of the Danish line, the Trekoner Fortress and a few ships continued to fire.

A senior Danish officer, Adjutant General Lindholm, went on board Elephant to negotiate, directing the Trekoner Fortress to stop firing on his way. The British ships also ceased fire and the battle effectively ended.

Danish floating battery and ship of the line under fire at the Battle of Copenhagen on 2nd April 1801 in the Napoleonic Wars

Defiance (Rear Admiral Graves’ Flagship: Captain Retalick, 74 guns) and Elephant went aground and the Danish Flagship, Dannebroge (Captains Fischer and Braun, 80 guns), grounded and blew up, with substantial casualties.

The next morning, 3rd April 1801, Nelson went aboard the Danish ship Syaelland, anchored under the guns of the Trekoner Fortress, and took the surrender of her captain Stein Bille, who refused to strike to any officer other than Nelson himself.

British destroying Danish ships under repair after the Battle of Copenhagen on 2nd April 1801 in the Napoleonic Wars

British gunboats took the Danish vessel in tow to add to the clutch of Danish ships that had been taken in the battle. 19 Danish vessels were sunk, burnt or captured.

Just before the Battle of Copenhagen, on 24th March 1801, the Tsar of Russia, Paul I, was murdered by members of the St Petersburg court, and replaced by his anti-French son, Alexander I. The effect of the Battle of Copenhagen and the Tsar’s murder was to bring about the collapse of the Northern Confederation.

Casualties at the Battle of Copenhagen:

British casualties were 253 men killed and 688 men wounded. No British ship was lost. The Danes lost 790 men killed, 900 men wounded and 2,000 made prisoner.

Destruction of the Danish Fleet at the Battle of Copenhagen on 2nd April 1801 in the Napoleonic Wars: picture by Thomas Whitcombe

Admiral Nelson writing the letter to the Danish Crown Prince at the Battle of Copenhagen on 2nd April 1801 in the Napoleonic Wars: picture by Thomas Davidson

Anecdotes and traditions from the Battle of Copenhagen:

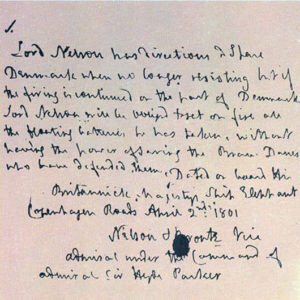

The letter Admiral Lord Nelson sent to the Crown Prince of Denmark at the Battle of Copenhagen on 2nd April 1801 in the Napoleonic Wars

- The letter Nelson sent to the Crown Prince by Captain Thesiger stated: Lord Nelson has directions to spare Denmark when no longer resisting but if the firing is continued on the part of Denmark Lord Nelson will be obliged to set on fire all the floating batteries he has taken, without having the power of sparing the Brave Danes who have defended them. Dated on board his Britannick Majesty’s ship Elephant Copenhagen Roads April 2nd 1801 Nelson & Bronté Vice Admiral under the command of Admiral Sir Hyde Parker. (Nelson’s signature referred to the title of Duke of Bronté (Duca di Bronté), conferred on him by the King of Sicily after the Battle of the Nile).

- Nelson considered the Battle of Copenhagen to be his hardest fought fleet action. Although hampered by many of their ships being unprepared for service, the Danes fought fiercely and, at times, with desperation in defence of their capital city, relays of army and civilian reinforcements replacing the losses in the batteries.

- The battle sealed Nelson’s reputation as Britain’s foremost naval leader. Soon afterwards, Sir Hyde Parker was recalled and Nelson left in command of the operations in the Baltic.

- The incident with the signal became an important part of the Nelson legend.

- The attack on Copenhagen, considered essential by the British to prevent the Danish Fleet from acting in the French interests, caused great resentment against Britain in Denmark. On Nelson’s return to England and appearance at court, King George III did not mention the battle.

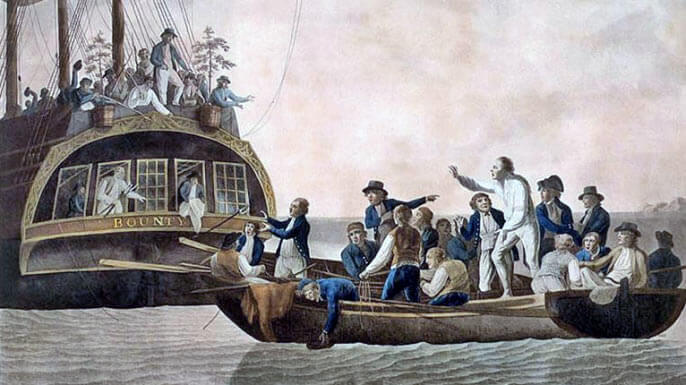

- His Majesty’s Ship Glatton was commanded in the battle by Captain William Bligh who had, in 1789, commanded HMS Bounty on its trip to the Pacific and been cast adrift in a ship’s boat by mutineers.

-

Naval General Service medal 1793-1840 with Copenhagen clasp and badge of the 95th Rifles: Battle of Copenhagen on 2nd April 1801 in the Napoleonic Wars

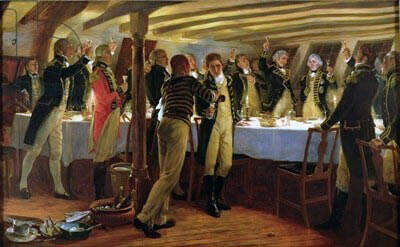

On the night before the Battle of Copenhagen, Nelson entertained the ship’s officers of HMS Elephant to dinner, giving the toast ‘to a fair wind and victory’.

- A detachment of soldiers, the 49th Regiment, a company of what would become the 95th Rifles and Royal Artillery, served with the Fleet at the Battle of Copenhagen. Some of these solders claimed the Naval General Service Medal 1793-1840 with the clasp ‘Copenhagen’ when it was issued in 1847, among them Private Steff of the 95th, who served on HMS Isis during the Battle of Copenhagen.

References for the Battle of Copenhagen:

Life of Nelson by Robert Southey

Nelson by Carola Oman

British Battles on Land and Sea edited by Sir Evelyn Wood

British Battles by Grant

The previous battle of the Napoleonic Wars is the Battle of Alexandria

The next battle of the Napoleonic Wars is the Battle of Trafalgar