The British victory in Egypt, 8th to 21st March 1801, over Napoleon Buonaparte’s vaunted veterans of the Army of Italy

73. Podcast on the Battle of Alexandria: the British victory in Egypt, fought between 8th and 21st March 1801 during the French Revolutionary War, over Napoleon Buonaparte’s vaunted veterans of the Army of Italy: John Mackenzie’s britishbattles.com podcasts

The previous battle in the Napoleonic Wars is the Battle of the Nile

The next battle in the Napoleonic Wars is the Battle of Copenhagen

War: French Revolutionary War

Date of the Battle of Alexandria: 8th to 21st March 1801

Place of the Battle of Alexandria: Alexandria on the Egyptian Mediterranean Coast

Combatants at the Battle of Alexandria: British against the French.

Commanders at the Battle of Alexandria: Lieutenant General Sir Ralph Abercromby against the French General Menou.

Size of the armies at the Battle of Alexandria:

The British army that landed at Aboukir in Egypt numbered 15,000.

The French ‘Armée de L’Est’ in Egypt was estimated to number around 30,000 men. Many of these troops were in garrisons across Egypt. The French army that gathered in Alexandria to confront the British army of General Abercromby numbered around 10,000 men.

Winner of the Battle of Alexandria:

The British.

British Order of Battle:

Lieutenant General Sir Ralph Abercromby in command

Guard’s Brigade (Major General Ludlow): 1st Coldstream Guards and 1/3rd Foot Guards

1st Brigade (Major General Coote): 2nd/1st (Royals), 2 Battalions of 54th Regiments and 92nd Highlanders

2nd Brigade (Major General Craddock): 8th (King’s), 13th, 18th and 90th Regiments

3rd Brigade (Major General Lord Cavan): 50th Regiment and 79th Cameron Highlanders

4th Brigade (Major General Doyle): 2nd (Queen’s), 30th, 44th and 89th Regiments

5th Brigade (Major General John Stuart): Minorca Regiment, De Roll’s and Dillon’s Regiments

Reserve (Major General Moore, Brigadier General Oakes): 23rd Royal Welch Fusiliers, 28th Regiment, 42nd Black Watch, 58th and 4 Cos 40th Regiments and Corsican Rangers

Cavalry (Brigadier General Finch): 1 troop 11th Light Dragoons, 12th, 26th and Hompesch’s Light Dragoons

Artillery: 700 all ranks with twenty-four light 6 pounders, four light 12 pounders, twelve medium 12 pounders and six 5 ½ inch howitzers.

Siege pieces: four 12 pounders, twenty 24 pounders, two 10 inch and ten 8 inch howitzers, eighteen 5 ½ inch, ten 8 inch and twelve 10 inch mortars

Background to the Battle of Alexandria:

In April 1798, following his victories in Italy over the Austrians, General Napoleon Buonaparte persuaded the Directory in Paris to permit him to launch an expedition in Egypt to capture the country from the Ottoman Empire and begin a threat to the British position in India.

On 19th May 1798 the French fleet sailed from Toulon carrying, after meeting convoys from Corsica and Italy, 30,000 troops from Buonaparte’s ‘Army of Italy’, hotly pursued by Admiral Nelson with his British fleet.

Buonaparte captured Malta on 12th June 1798 and sailed on to Egypt.

Admiral Nelson arrived off Alexandria on 28th June 1798 and, finding no sign of the French, sailed on to continue his search.

The French fleet arrived at Alexandria on 1st July 1798 and Buonaparte disembarked his army and began his invasion of the Turkish colony of Egypt.

Buonaparte took Cairo and conquered Lower Egypt, heavily defeating the Mamelukes at the Battle of the Pyramids on 21st July 1798.

In the meantime, Nelson returned to Egypt and, surprising the French fleet, virtually annihilated it at the Battle of the Nile on 1st August 1798, leaving Buonaparte and his army stranded in Egypt.

In March 1799, Buonaparte invaded Syria, laying siege to Acre, defended by a garrison of Royal Navy sailors and Turkish troops commanded by Captain Sir Sidney Smith Royal Navy.

After nine weeks, Buonaparte abandoned the siege of Acre and retreated to Egypt, having suffered 5,000 casualties to battle and disease.

It became clear to Buonaparte that it was in his own pressing interest for him to return to France.

On 22nd August 1799, Buonaparte secretly embarked for France, telling only General Kléber, his successor in command in Egypt, of his clandestine departure, leaving his troops in ignorance of his desertion of them.

Buonaparte returned to France to become First Consul of the Republic on 25th December 1799.

In late 1800, Lieutenant General Sir Ralph Abercromby was ordered by the British Government to take 15,000 British troops to Egypt and capture the port city of Alexandria.

The French army in Egypt was believed to number around 15,000 men. In fact, the number was nearer to 30,000.

However, the British government was correct in its belief that the French soldiers were ‘very anxious to return home’.

An offer was to be made to the French commander in Egypt to provide transports to convey his army to France. If he refused, the offer was to be made known to the French rank and file.

Arrangements were put in train to convey an additional force of British and Indian troops from India to advance into Egypt from the east coast.

The British fleet conveying Abercromby’s troops to Egypt was routed via Minorca and Malta.

The fleet left Gibraltar at the end of October 1800 and reached Malta at the end of November 1800.

In Malta a number of the transport ships were emptied and repaired.

On 15th December 1800, Abercromby’s army numbered 16,000 fit men and 1,270 sick men. There were only some 400 cavalry in this number and the cavalrymen were almost entirely without horses.

Abercromby’s expedition sailed from Malta and arrived in Marmorice Bay on the coast of modern Turkey on 29th and 30th December 1800.

The purpose of Abercromby’s stay in Marmorice Bay was to receive food and other stores and horses for his cavalry, to be supplied by the Ottoman authorities on the Island of Rhodes. None were forthcoming.

In addition, neither the Ottoman fleet nor its army in Jaffa was in a position to assist Abercromby in his attack on the French in Egypt.

One of the pressing problems for Abercromby was how to supply his army with water once it had landed on the desert plains of the Egyptian coast. Until Alexandria was taken the army would have to rely on the Fleet for its water.

Abercromby had experience of the disastrous outcome to landing on a hostile shore with inadequate preparation and ill-trained troops, from the landing at Helder in the Netherlands in 1799.

Abercromby issued full instructions to the fleet and army for the landing, which was to be made in three lines of boats provided by the fleet. The formation for the boats was laid down in detail. The troops were to sit in the boats with muskets unloaded without movement or noise. Once landed the troops were to form up on the shore.

The landing procedures were practised in Marmorice Bay until all knew their parts thoroughly.

The 12th and 26th Light Dragoons joined the army, but without horses, which Abercromby was unable to supply due to the lack of Ottoman assistance.

Meanwhile Buonaparte, concerned for the safety of his army in Egypt, sent Admiral Ganteaume’s squadron from Brest to convey re-enforcements to Egypt.

Of the various ships sent only three French frigates managed to reach Alexandria, carrying supplies and additional troops.

British ships intercepted many of the French vessels sailing between France and Egypt, preventing further re-enforcement of the French army and supplying Abercromby with information on the state of the French in Egypt.

The French troops were not in a good state of discipline, having to rely upon local sources for food and drink and resenting their continued exile from France.

The command of General Kléber, a popular and competent commander, kept the French troops in hand.

In May 1800 Kléber was assassinated by an Egyptian fanatic. Command of the French army in Egypt devolved on General Jacques-François de Menou.

Menou declared Egypt to be a French colony, bringing him into conflict with the existing local authorities. Menou was also in conflict with his own divisional commanders, particularly with Reynier.

On 22nd February 1801, the British fleet with Abercromby’s army set sail for Egypt. Two British engineer officers were sent ahead to reconnoitre the landing beach.

In March 1801 the French army in Egypt numbered around 30,000 men, of which some 6-7,000 were either on the sick list or in permanent garrisons across the country.

Menou’s total available force for the field was 15,200 infantry and gunners and 1,700 cavalry. Of these the main body of French troops was in Cairo with Menou and amounted to 8,000 men.

The French force in Alexandria amounted to 2,000 troops, with a further 2,000 seamen and invalids, commanded by General Friant.

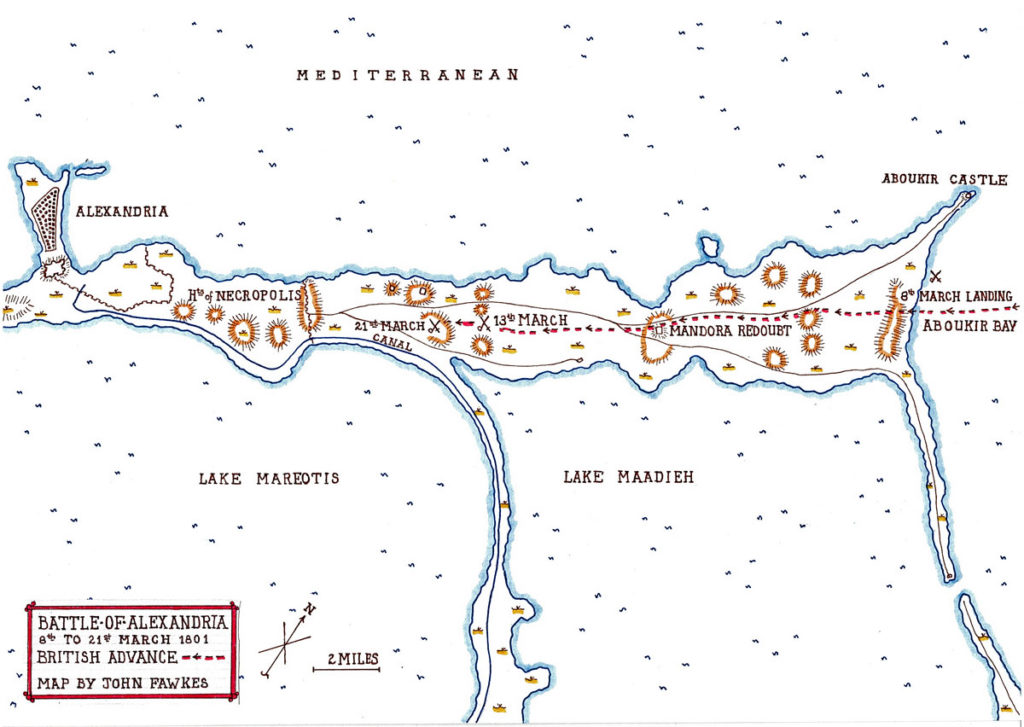

The city-port of Alexandria lay at the end of a 13-mile-long isthmus running to Aboukir Bay. On one side of the one- to two-mile-wide isthmus lay the Mediterranean Sea and on the other the Lakes of Mariotis and Maadieh.

Friant took up positions at Aboukir with 1,600 men (61st and 75th demibrigades, companies from the 51st and 25th demibrigades, 18th Dragoons and a detachment from the 20th Dragoons). He also occupied Aboukir Castle, standing on the northern end of Aboukir Bay, equipped with eight 24 pounders and two 12-inch mortars.

A block house at the south-eastern end of Aboukir Bay contained another heavy gun, possibly more.

In answer to Friant’s request for assistance, Menou made some minor movements of troops, reinforcing Alexandria with a further 600 men.

Battle of Alexandria:

The British fleet commanded by Admiral Keith with Abercromby’s army on board came to anchor off Aboukir Bay on the morning of 2nd March 1801.

Abercromby found that one of the engineer officers had been killed and the other made prisoner. He therefore set off in a fleet cutter with his second in command, Major General John Moore, to carry out his own reconnaissance of the landing beach.

The beach was at the north-eastern end of the 13-mile-long narrow isthmus leading to the city of Alexandria.

The beach was crescent shaped, two miles in length, with the Castle of Aboukir at the north-western end and hills running from the centre of the bay to the south-eastern end, where there the block-house stood.

The guns in Aboukir Castle precluded a landing anywhere on the north-western half of the bay. The landing would need to be made on the hilly section running from the centre of the bay to the south-east.

No sign of field fortifications in the hilly section could be detected by the British generals. An armed French vessel anchored under the castle walls as the inspection was taking place.

Abercromby and Moore selected points for the landing in the south-eastern section of the beach and returned to the fleet.

Abercromby ordered that the landing take place the next day, but a gale blew up and continued for four days, precluding any landing.

The gale blew out on 7th March 1801 and Abercromby ordered the landing for the next morning.

The Landing in Aboukir Bay on 8th March 1801:

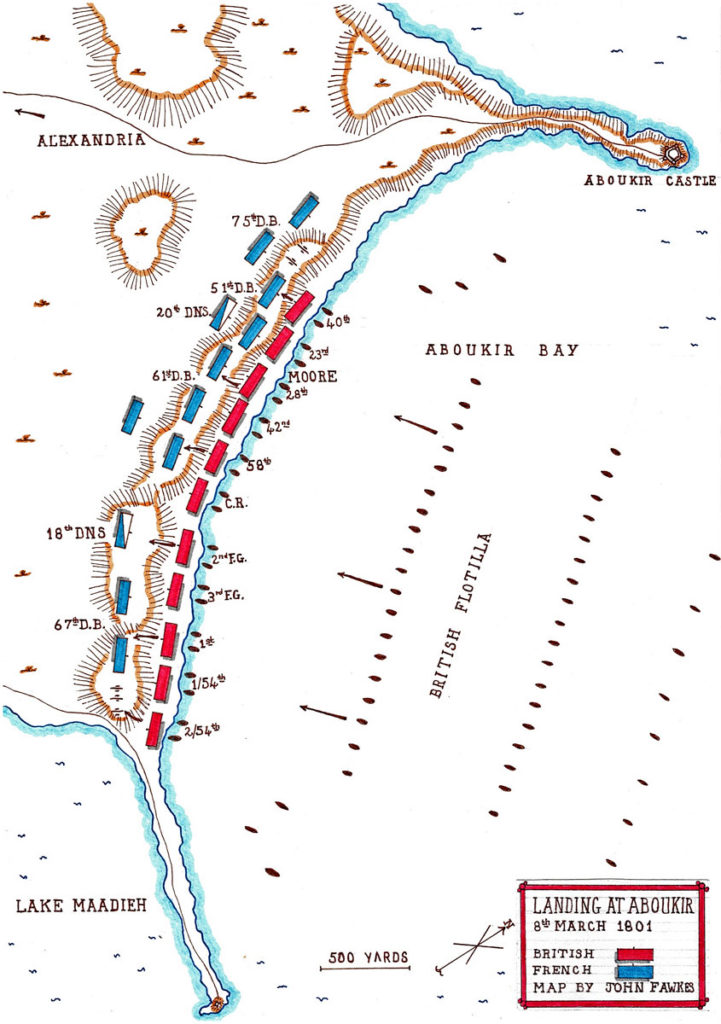

The orders for the British landing were that the Reserve commanded by Moore was to take the right, landing on the central hilly section of the coast, with, to its left, the Guards Brigade, the 1st Royal Scots and the 54th Regiment.

The other regiments were to form the second and third waves.

During the evening of 7th March 1801 two boats were moored to mark the points between which the landing boats were to form up.

The troops of the second line were transferred to vessels with shallow draught to be brought closer to land.

The start of the landing was signalled by a rocket fired from the flagship and the boats were rowed to the transport ships and the troops loaded on board.

By 3.30am on 8th March 180, the flotilla was under way to cover the 5 miles to the rendezvous.

By 9am the flotilla was drawn up and the first line of 58 flat boats set off for the landing beach, followed by the second line comprising 84 cutters and the third line of 37 launches.

Each of the small craft carried around 50 soldiers, sitting with unloaded muskets and carrying three days provisions and sixty rounds of ammunition.

In the rear of these three lines were 14 cutters, each with a gun and a crew of seamen and gunners, commanded by Captain Sir Sidney Smith.

On each wing of the flotilla were two gunboats and a bomb ship.

Three more vessels of light draught moored close to the shore to provide gun support with their broadsides to the landing troops.

As the landing craft approached the shore, the French guns in Aboukir Castle, the Blockhouse and positioned along the sandhills opened fire.

A shell hit a boat carrying Coldstream Guardsmen, killing and wounding many and throwing the remainder into the sea.

This incident caused a section of the line of boats to swerve to the left.

As the boats approached the shore, the French infantry on the sand hills along the shoreline opened musketry fire on the British.

Moore’s reserve brigade headed undeviating towards the great sand-hill in the centre of the bay.

Moore’s brigade grounded and the soldiers of the 40th, 23rd Royal Welch Fusiliers and 28th Regiments leaped ashore.

Moore led the troops straight up the sandhill, without pausing to load.

The French 61st Demi-Brigade held the summit of the sandhill, but, as the British troops appeared at the top of the forward slope, the French were driven from the hill-top and hunted back through the sandhills into the plain, the British capturing 4 guns.

Moore halted his men and waited for the results of the rest of the landings. It had taken him twenty minutes to take the great sand-hill.

On Moore’s left, the 42nd landed with the 58th in support. The Highlanders formed up and loaded, in time to meet an attack by French cavalry, which they repelled with volleys.

On their left the British Guards Brigade landed in some confusion due to the sinking of two of their boats.

An attack by the French cavalry was repelled with the assistance of the 58th Regiment, enabling the Guards to move forward.

On their left the 54th and Royal Regiments drove back a French battalion advancing to take the Guards in their left flank.

Major General Coote now launched an assault against the French, driving their sharpshooters out of the sandhills and after an hour and a half the French were pushed off the sandhills entirely, back into the plain, losing eight guns.

As the Royal Navy boats unloaded the initial landing force, they returned to the fleet to collect the rest of the army from the transports and land them.

The whole of Abercromby’s army was landed before dark and advanced into the plain where they halted for the night.

Casualties in the Landing:

The 42nd Black Watch suffered 21 men killed and 8 officers and 148 soldiers wounded.

The Coldstream Guards suffered 6 officers and 91 men killed, wounded or missing.

Total British casualties in the landing were 31 officers and 621 soldiers killed, wounded or missing.

The Royal Navy suffered 7 officers and 90 men killed or wounded.

British casualties were over 700 in all.

French casualties were 300 to 400 killed wounded or captured.

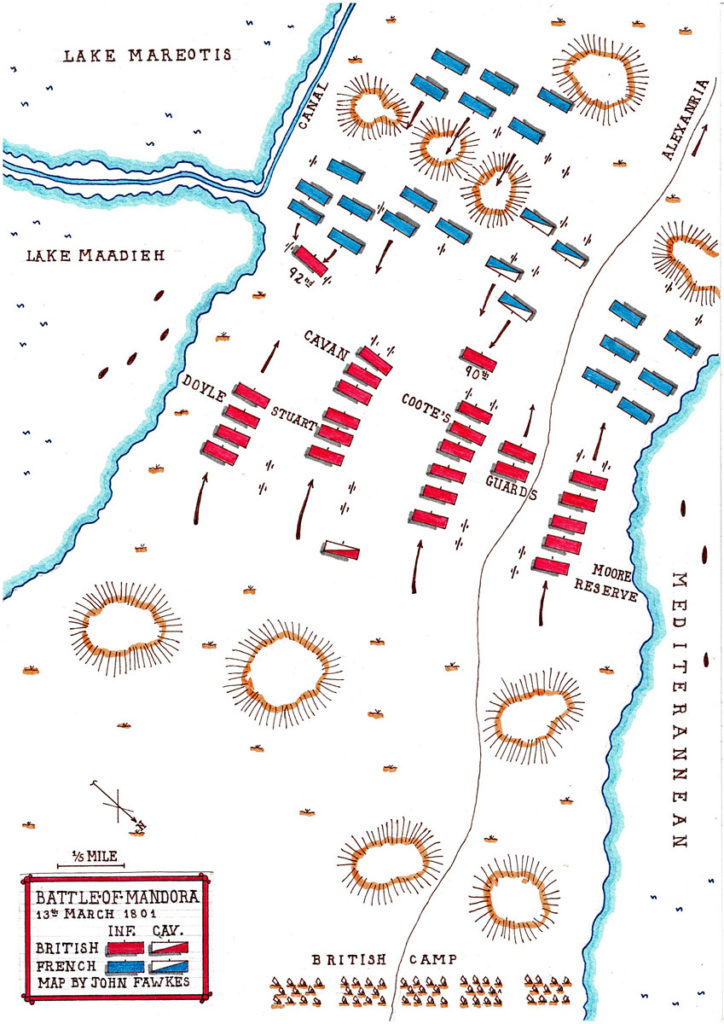

The British Advance on Alexandria, the battle for the Roman Camp on 13th March 1801, known as the Battle of Mandora:

Abercromby’s army now stood at the eastern end of a long thin strip of land, around a mile wide, that stretches along the Egyptian coast from Aboukir Bay for some 13 miles to the City of Alexandria, with Lake Maadieh and the much larger Lake Mareotis on the southern side and the Mediterranean Sea on the northern side.

The surface of the strip of land was largely sand, dotted with palm trees, making marching arduous.

The pressing need for the army as it waited for its supplies to be landed from the fleet was for water.

Captain Sir Sidney Smith instructed the soldiers to dig in the area of the palm trees and by doing so a ready supply of water was found.

On 9th and 10th March 1801, the wind resumed, preventing the landing of stores from the fleet and the army remained stationery.

General Friant, the French commander in Alexandria, drew in all his detachments, other than the garrison in Aboukir Castle and stationed his army, with the reinforcement of General Lanusse’s division, on the Heights of Nicopolis outside Alexandria, his force being around 5,000 men with 21 guns.

While Abercromby’s army waited for its stores to be landed, Moore’s Reserve moved forward and the 2nd Queen’s Regiment with 400 dragoons took over the blockade of Aboukir Castle.

On 11th March 1801, the landing of supplies from the fleet began and the few horses were transferred to the shore.

The problem of moving supplies and reserves of ammunition once ashore was met by Royal Navy gunboats breaking through into Lake Maadieh and moving along the shore in parallel with the troops.

The lack of experience of the French High Command in dealing with maritime matters was shown by their failure to appreciate the importance of blocking the entrances to Lake Maadieh from the sea.

On 12th March 1801 Abercromby’s army began its march along the isthmus towards Alexandria.

The French cavalry retired in front of them until they reached the main body of the French army advancing towards the British.

The French took up positions along the heights across the isthmus at the western point of Lake Maadieh.

Lake Mareotis at this time of year was largely dry.

Between Lake Mareotis and Lake Maadieh ran a narrow strip of land carrying the canal from Alexandria to the hinterland of Egypt, forming the only viable communication for the city with the interior and along which any reinforcements for Friant’s army from General Menou would have to pass, or so Friant assumed on the basis that even where dry, Lake Mareotis was impassable to guns.

Friant considered it important to prevent the British from cutting off this route to Alexandria.

Abercromby halted his army and resolved to attack the French the next day.

The heights, running obliquely across the isthmus were known as the Roman Camp. The French left was around some old buildings.

Abercromby advanced to the attack with the aim of turning Friant’s left flank at 6.30am on 13th March 1801.

Moore’s Reserve, marching in column through the heavy sand, took the right flank, by the sea. Coote’s and the Guards Brigades formed the central column, with Cavan’s, Stuart’s and Doyle’s Brigades and a battalion of Marines forming the left column.

Royal Navy sailors dragged the guns through the sand, in the absence of horse teams.

The whole army was preceded by an advanced guard of the 90th Regiment marching in front of the centre column and the 92nd Highlanders with two guns in front of the left column.

The small force of dragoons marched between the right and centre Columns.

Abercromby’s army numbered some 14,000 men.

As the British advanced, they were subjected to a heavy fire from the French guns on the heights.

The difficulty of dragging the guns through the sand delayed the main British columns and the two advanced regiments outdistanced them.

The undulations in the ground concealed the centre column from the French on the high ground and they supposed the 90th and 92nd Highlanders to be unsupported.

Friant, acting on a suggestion from Lanusse, deployed 1,800 men with guns to contain Moore’s right column, while the rest of the French army fell on the advanced regiments and the left column.

The French 22nd Chasseurs à Cheval caught the 90th Regiment in the course of deploying into line.

The massed 90th held their fire until the French cavalry were almost upon them and shattered the Frenchmen with a volley fired at a few yards distance.

The French infantry came up and fell upon the 90th and 92nd, which fought hard to hold them.

The British centre and left columns came up and joined the fighting with the French.

Moore’s Reserve on the British right and Doyle’s Fourth Brigade on the British left continued their advance in column.

The French began to fall back under the pressure, the 92nd Highlanders capturing three guns in the French position.

The French horse artillery particularly distinguished themselves, retiring a short distance before halting and firing a number of rounds at the slowly advancing British infantry, before limbering up and withdrawing a further short distance and repeating the process.

The British Reserve and Craddock’s Brigade on the British right was in advance of the rest of the line and advanced onto the heights of the Roman Camp, causing the French to abandon that position.

There, Moore and Craddock halted to allow the rest of the British troops to come up.

On the left, Dillon’s Regiment stormed a French fieldwork on the Alexandra canal bank, allowing the rest of the British line to move forward, the threat to its left flank removed.

The French fell back to the next line of hills in front of the Alexandria fortifications.

Abercromby halted on the line of hills taken by Moore and Craddock, the Roman Camp and summoned his senior generals, Moore and Hutchinson for a consultation.

The French were now in front of their main position, a chain of fortified heights known as the ‘Heights of Nicopolis’.

Abercromby failed to see what a formidable position this was and ordered attacks on the French by Hutchinson on the left flank with the Third, Fourth and Fifth Brigades, while Moore attacked simultaneously on the right with the Reserve.

The remainder of the British troops were to lie down where they halted.

Hutchinson marched to a bridge across the Alexandria Canal, intending to approach the French left across a dried-up section of Lake Mareotis.

The bridge was defended by French infantry with a howitzer but was stormed by the British 44th Regiment.

The rest of Hutchinson’s column was subjected to a heavy bombardment by the French guns on the heights and it became clear to Hutchinson what a strong position the French were occupying, causing him to halt and await further orders.

Abercromby sent Colonel John Hope of his staff to report on the strength of the French right.

In the meantime, the British infantry were subjected to a lengthy and damaging bombardment by the French guns.

It was now evening. Abercromby resolved to abandon the attack and his army fell back to the Roman Camp position.

French casualties in the day’s fighting were around 500 officers and soldiers killed, wounded or captured.

British casualties were Army: 6 officers and 150 men killed, 66 officers and 1016 men wounded. The Royal Navy, crewing the gunboats and Marines suffered 3 officers and 27 men killed and 4 officers and 50 men wounded.

The 90th Regiment suffered 240 casualties and the 92nd Highlanders 140 casualties.

The day saw Abercromby’s army well advanced and with 5 captured guns.

Abercromby was now beyond the end of Lake Mareotis and could no longer rely on the Royal Navy’s gunboats to transport his supplies. Lacking sufficient horses or carts the troops were compelled to carry the supplies themselves over the difficult sandy hills.

The British troops were set to digging entrenchments in defence of the Roman Camp ridge.

This feature comprised a central ridge with a further ridge on the right, next to the sea.

Areas of flat ground lay between the two ridges and between the central ridge and the shore of Lake Mareotis on the southern side.

The ridge on the right flank, next to the sea, was called the ‘Roman Camp’ and was surmounted by an old building. Moore and his Reserve were positioned on the Roman Camp ridge.

Field-works were dug on the central ridge and a number of guns installed, two 24 pounders and 34 field guns.

The Central Ridge was held by the Guards’ and Coote’s Brigades with Craddock’s Brigade between the Central Ridge and Lake Mareotis.

In the British second line, behind the Roman Camp ridge, were the brigades of Stuart, Doyle, Finch and Cavan.

Royal Navy gunboats covered the British Right Flank from the sea.

By the 18th March 1801, the British sick list reached 3,500 due to the burden building the field fortifications and moving supplies.

In a cavalry skirmish, the British 26th Light Dragoons rashly suffered casualties of 5 officers, 25 men and 42 horses killed, wounded or captured.

On that day the French garrison surrendered Aboukir Castle to the British.

On 19th March 1801, General Menou crossed by a dried-out section of Lake Mareotis and reached Alexandria with reinforcements of infantry, cavalry and guns, increasing the French force to 10,000 men, including 1,400 cavalry with 46 guns.

Menou was aware that a British force from India under General Baird was due to arrive on the Red Sea coast and that the Turkish army was finally on the move. Menou determined to take the initiative and attack Abercromby’s army on the Roman Camp Ridge.

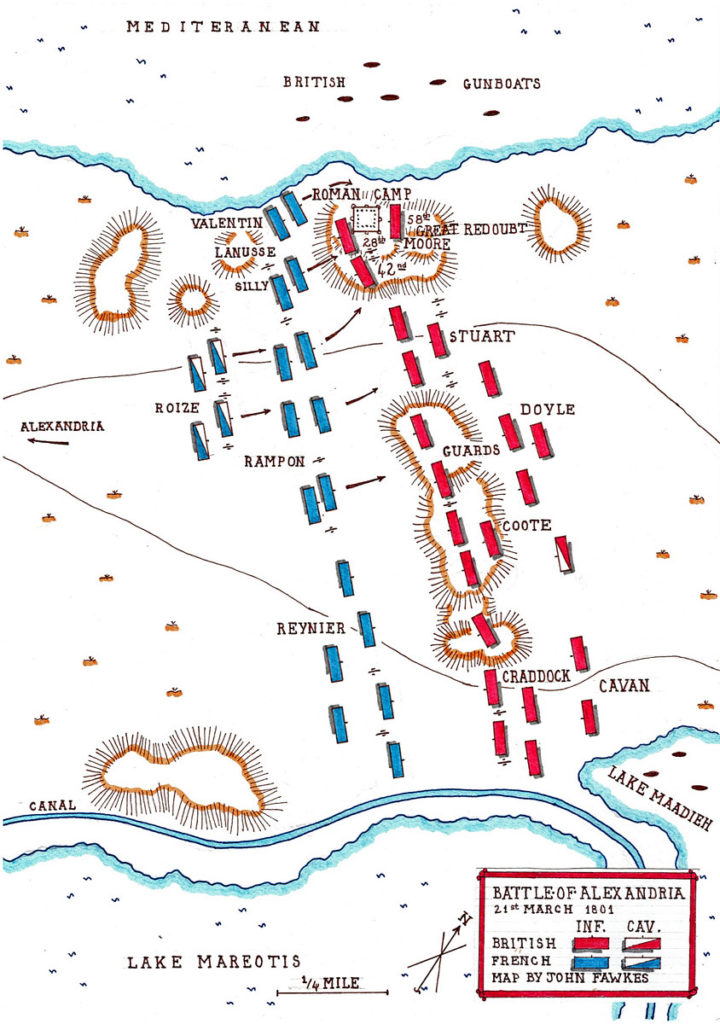

Menou’s plan was for Lanusse’s Division of 2,700 men to attack the British position on Roman Camp ridge by the Mediterranean before dawn, to be followed by an attack by Rampon’s Division of 2,000 men on the central ridge, supported by Reynier’s Division of 3,500 men, which was also to hold the British left in check.

A force of 900 cavalrymen under General Roize was to remain in reserve and complete the overthrow of the British with a charge down the isthmus once the infantry had successfully carried the British positions.

The Battle to take the Roman Camp ridge on 21st March 1801:

The French attack was launched before dawn to take the British by surprise, Menou making the reasonable assumption that Abercromby would be unlikely to be aware of his arrival with a strong force in Alexandria.

Nevertheless, Abercromby issued orders on the 20th March 1801, warning of the likelihood of a night attack by the French and giving orders that the troops were to sleep fully equipped in their forward positions and be under arms half an hour before dawn.

Moore was major general of the day on 21st March 1801.

Soon after 5am Moore heard firing from the British left.

Moore was making his way there when heavy firing broke out on the British right.

‘This is the real attack’ Moore commented and rode hard to the Roman Camp Redoubt.

Lanusse’s Division was attacking the British right, Valentin’s Brigade advancing in column along the seashore while Silly’s Brigade launched a direct attack on the redoubt.

Silly’s Brigade took an advanced fleche, but was repelled by volleys from the 28th Regiment, commanded by Paget, in its attack on the main redoubt, swerving to the left of the redoubt.

Valentin’s Brigade turned to its right and climbed the hillside,

its right battalion climbing towards the north-west face of the redoubt, the left battalion advancing into the space between the redoubt and the ruined building.

The right battalion was met with a storm of grapeshot and reeled back. Lanusse, in attempting to rally them was mortally wounded, the battalion streaming back.

The left battalion, caught in a cross-fire between the British 28th and 58th Regiments also reeled back.

Rampon’s Division advanced on Lanusse’s right. His left brigade, disorientated in the darkness, became entangled with Silly’s brigade.

Rampon’s right brigade advanced along the low ground between the Roman Camp and the Central Ridge and its leading battalion, turning to its left, advanced up to the Roman Camp ridge from the rear.

Moore ordered a wing of the 42nd and soldiers from the 28th to face about, driving Rampon’s stray battalion to take shelter in the building, where they were met by the 23rd and the 58th, every man in the French battalion becoming a casualty or a prisoner.

Moore re-formed the 42nd and led them to the left flank of the Redoubt where they encountered the rear battalion of Silly’s Brigade, driving it back.

Moore received a wound in the leg, while the 42nd and 28th pursued Silly’s retreating battalion.

Menou now launched the first line of his reserve of cavalry to attack these two British regiments, which were harried back into the area around the Redoubt.

The French horsemen here came to grief in a number of holes dug by the British troops for shelter in the absence of tents.

The 42nd, rallying, attacked the French cavalry, driving them back with heavy loss.

With daylight, Silly’s leading battalion renewed the attack on the redoubt at its north face, the point where Valentin’s battalions had been driven back.

These troops came under heavy fire from the 58th Regiment in their front and the Royal Navy gunboats off the coast to their rear. The French attack collapsed.

To the right of Lanusse’s Division, Rampon’s Division attacked the British Guards Brigade. Driven back by heavy volleys, Rampon directed his men around the left flank of the British Guards.

Several companies of the Third Guards were drawn back to meet this attack, but suffered heavily until relieved by the advance of the Royal Scots of Coote’s Brigade, whereupon Rampon withdrew.

In a final effort, Menou ordered General Roize to attack with his second line of cavalry. The 500 troopers of three cavalry regiments charged up the southern ridge of the Roman Camp while part of the line attacked the Central Ridge.

The French cavalry were supported by an advance of part of Reynier’s Division.

The French cavalry broke through the 42nd Highlanders on the southern edge of the Great Redoubt. Moore managed to gallop clear of the French attack, but Abercromby was taken prisoner, although immediately rescued by a highlander of the 42nd.

The 42nd, broken up into small groups, fought on resolutely and the 28th Regiment faced about and shot down those French cavalrymen who managed to penetrate into the rear of the Great Redoubt.

The 40th Regiment destroyed the main party of the left of Roize’s brigade with two volleys.

Roize’s right hand squadrons charged into the gap between the Roman Camp and the Central Ridge where they broke through Stuart’s Minorca Regiment, receiving volleys as they passed and a further devastating fire as they attempted to return.

The French attack had been decisively repelled. The confused remnants of Lanusse’s and Rampon’s Divisions remained scattered among the sandhills at the bottom of the ridge.

By this time the first line British regiments were largely out of ammunition, as were many of the French troops attacking the Roman Camp Ridge.

The French guns came forward and continued to fire at maximum elevation, inflicting loss on the British second line behind the two ridges.

Abercromby rode to a fieldwork at the northern end of the central ridge. He was complaining of a blow to the chest, but he had also been shot in the thigh.

Ammunition was brought up and the British guns resumed their fire on the French.

Menou declined to withdraw, until two French ammunition waggons were detonated by British shells. The French then withdrew to their positions on the Heights of Nicopolis in good order. The battle was over.

Casualties in the Battle of Alexandria:

Fortescue assesses that the numbers of troops on each side actually involved in the fighting in the battle were roughly the same, with the French having a slight advantage.

Moore by keeping his battalions concealed behind field fortifications kept their casualties low.

The 28th, although heavily involved in the fighting, suffered only 4 officers and 70 men killed or wounded.

The 23rd, 58th and 40th, also in the Great Redoubt fortifications, suffered less than 50 casualties between them.

The battalions caught up in the French cavalry charge suffered heavily.

The 42nd Black Watch suffered casualties of 4 officers and 48 men killed and 8 officers and 253 men wounded.

Stuart’s Minorca Regiment suffered casualties in its action against the French cavalry of 13 officers and 200 men killed or wounded.

The Third Guards suffered casualties of nearly 200 officers and men killed or wounded in the attack by Reynier’s Division.

Total British casualties were 10 officers and 233 men killed, 60 officers and 1,193 men wounded and 3 officers and 29 men missing (captured).

Soon after the end of the battle, Abercromby collapsed and the bullet wound in his thigh was discovered.

Abercromby was conveyed on board ship where he was operated upon. It was found that the bullet was too deeply embedded in his thigh to be extracted. Abercromby died from the consequences of gangrene on 28th March 1801. His body was taken to Malta where it was buried.

Of the other British generals, Moore was wounded, as were Oakes, Moore’s brigadier, Lawson, commanding the artillery and John Hope, the adjutant general.

The French left on the field over 1,000 dead, 600 wounded and 200 prisoners.

Fortescue calculates the total French casualties as being around 4,000 in all.

General Lanusse was killed commanding his division and Silly, a brigade commander, severely wounded. In Rampon’s Division both brigade commanders were wounded (Eppler and d’Estin). Baudot, brigade commander in Reynier’s Division was killed. General Roize of the cavalry was killed and his deputy severely wounded.

Aftermath to the Battle of Alexandria:

Following the death of General Abercromby, and the wounding of General Moore, General Hutchinson took over command of the British army in Egypt.

On 2nd September 1801, the French commander, General Menou, signed terms of capitulation whereby he surrendered the City of Alexandria and the French army in Egypt was transported back to France by the British Fleet.

Battle Honours and Medal for the Battle of Alexandria:

The Military General Service Medal 1848 was issued to all those serving in the British Army present at specified battles during the period 1793 to 1840, who were still alive in 1847 and applied for the medal. The medal was only issued to those entitled to one or more of the clasps.

‘Egypt’ was one of those clasps.

Equally, the Naval General Service Medal 1848 was issued to those serving in the Royal Navy during the period 1793 to 1840, who were still alive in 1847 and applied for the medal. The medal was only issued to those entitled to one or more of the clasps.

‘Egypt’ was one of those clasps.

‘Egypt 1801’ is a battle honour for the following British regiments: 11th and 12th Light Dragoons, Coldstream Guards, Third Foot Guards, 1st Royal, 2nd Queen’s Royal, 8th King’s, 10th, 13th, 18th, 20th, 23rd Royal Welch Fusiliers, 24th, 25th, 26th, 27th, 28th, 30th, 40th, 42nd Black Watch, 44th, 54th, 58th, 61st, 79th, 80th, 86th, 88th, 89th, 92nd and 97th Regiments.

Not all of these regiments were present at the Battle of Alexandria, some being in the force from India commanded by General Baird that landed on the south-east coast of Egypt.

In addition, the battle honour ‘Mandora’ was awarded to the 90th Regiment and the 92nd Highlanders for their part in the fighting on 13th March 1801.

Anecdotes and traditions from the Battle of Alexandria:

- When Abercromby’s force arrived in Malta one of the complications he faced was that he had two battalions from the 54th Regiment and four companies from the 40th Regiment comprising 1,500 militiamen engaged for service in Europe only. This problem was resolved when all ranks volunteered to serve in Egypt.

- Fortescue, writing at the end of the 19th Century describes the British Landing at Aboukir Bay as ‘perhaps the most skilful and daring operation of its kind that was ever attempted’: clearly hyperbole, but nevertheless a confirmation that for such an operation to succeed careful planning and frequent practice are essential: lessons relearnt in World Wars 1 and 2 at Gallipoli, Dieppe, North Africa, Sicily and D-Day.

- The French troops in Egypt were Buonaparte’s veterans from the Army of Italy. One of the captured French colours bore among its battle honours ‘the Bridge of Lodi’. After the Battle of Alexandria, French soldiers are reported as saying that ‘their work in Italy had been child’s play compared to the three actions of the 8th, 13th and 21st of March, and that they had never yet known what it was to fight.’

- Required to face about and repel the French attacks on the rear of the Great Redoubt, the 28th Regiment were awarded a ‘back badge’, which all ranks of the 28th wore on their head-dresses. This dress convention was continued by the Gloucesters, the successor regiment to the 28th. The ‘back badge’ was a Sphinx, the badge adopted by several of the regiments in Abercromby’s army.

References for the Battle of Alexandria:

History of the British Army by Sir John Fortescue Volume IV Part II

73. Podcast on the Battle of Alexandria: the British victory in Egypt, fought between 8th and 21st March 1801 during the French Revolutionary War, over Napoleon Buonaparte’s vaunted veterans of the Army of Italy: John Mackenzie’s britishbattles.com podcasts

The previous battle in the Napoleonic Wars is the Battle of the Nile

The next battle in the Napoleonic Wars is the Battle of Copenhagen