The last battle, fought on 16th June 1743, at which a British King was present, King George II: a victory for the Pragmatic Army led, nominally, by King George II

King George II with the Duke of Cumberland at the Battle of Dettingen on 16th June 1743 in the War of the Austrian Succession: picture by John Wootton

The previous battle in the British Battles series is the Battle of Malplaquet

The next battle of the War of the Austrian Succession is the Battle of Fontenoy

To the War of the Austrian Succession index

War: War of the Austrian Succession or King George’s War (the name in North America).

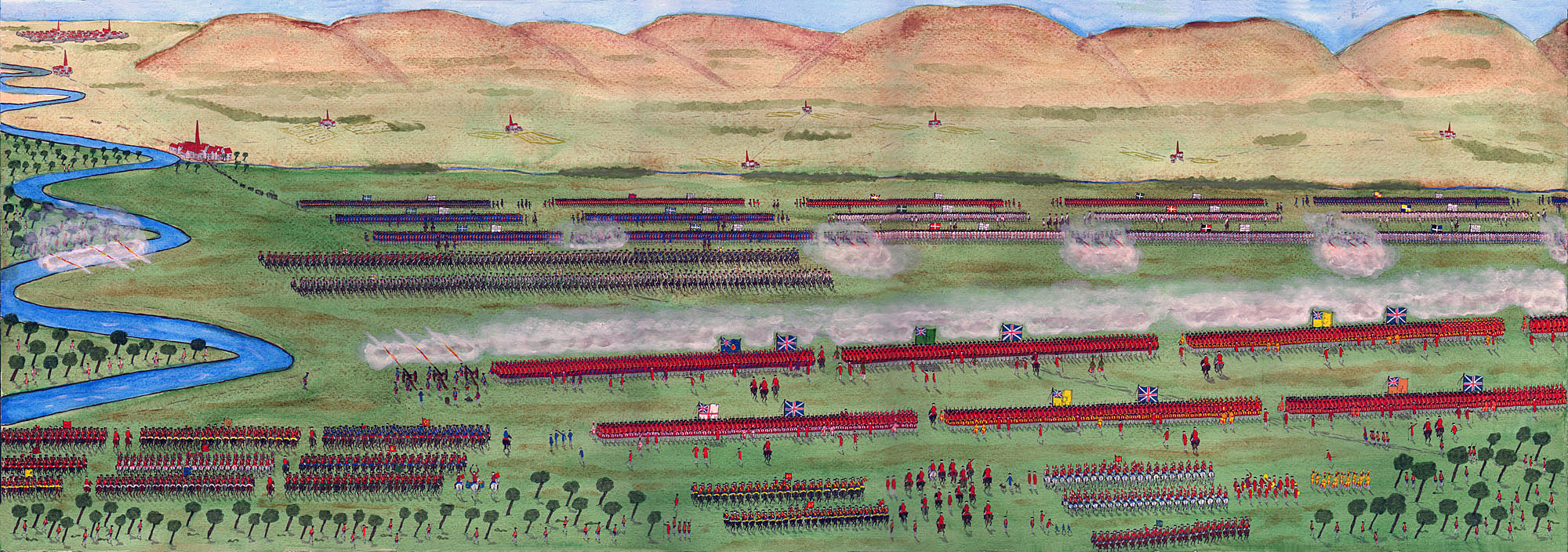

Battle of Dettingen on 16th June 1743 in the War of the Austrian Succession: picture by John Mackenzie

Date of the Battle of Dettingen: 16th June 1743 (old style) (new style: 27th June 1743)

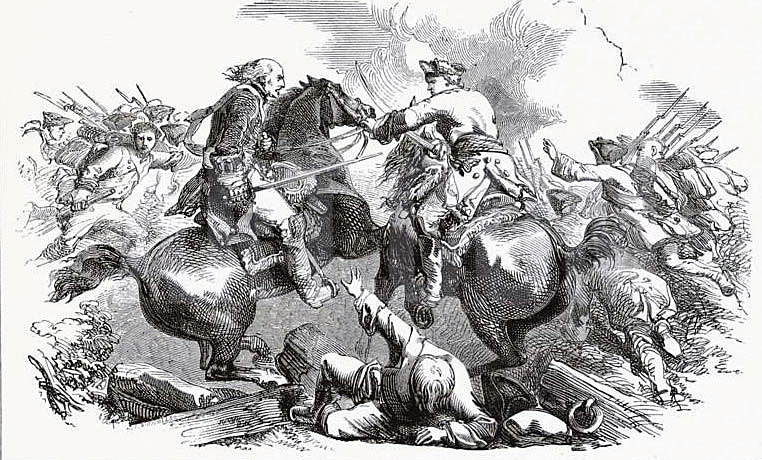

Battle of Dettingen fought on 16th June 1743 in the War of the Austrian Succession: picture by Henri Dupray

Duc de Noailles French Commander at the Battle of Dettingen fought on 16th June 1743 in the War of the Austrian Succession

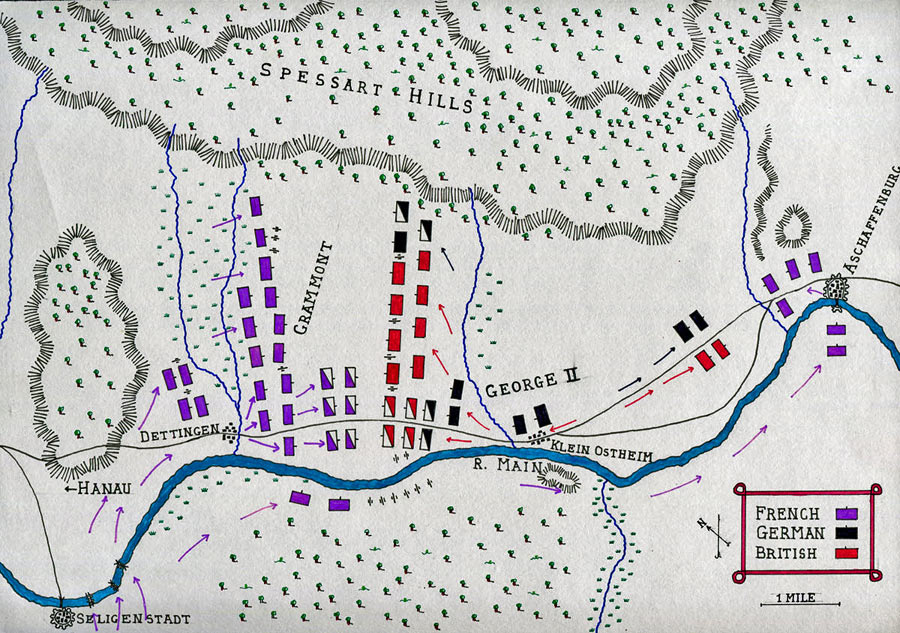

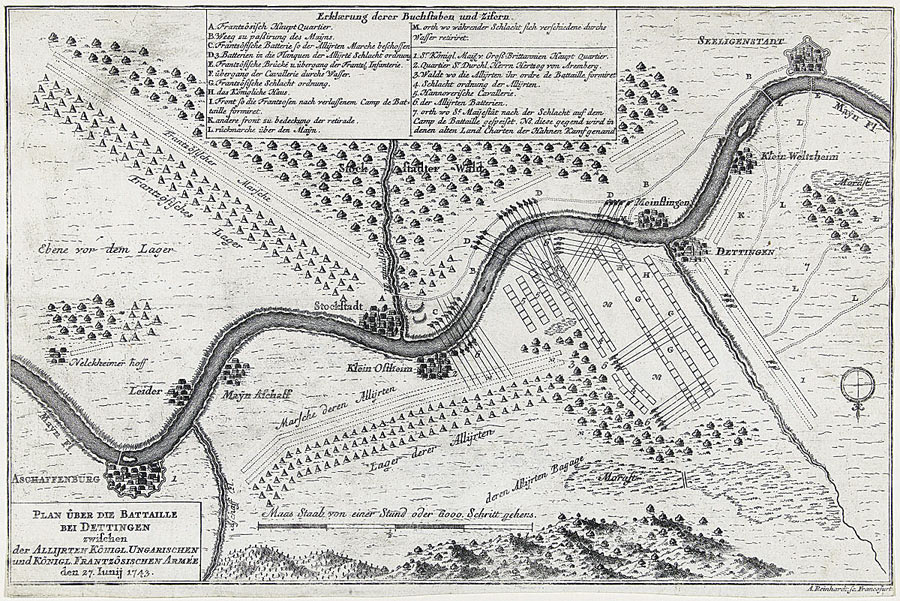

Place of the Battle of Dettingen: Dettingen was fought in South West Germany on the North bank of the Main river some 70 miles East of Frankfurt and 3 miles West of Aschaffenburg.

Combatants at the Battle of Dettingen: The Pragmatic Army comprising British, Hanoverians and Austrians against a French Army.

Generals at the Battle of Dettingen: George II, King of England and Elector of Hanover, Earl of Stair, Marshall Konigseck, Duc D’Ahremburg, General Ilton (Hanover). The French were commanded by the Duc de Noailles and the force that crossed the Main was commanded by the Comte de Grammont.

Size of the Armies at the Battle of Dettingen: 70,000 French and 50,000 British and allied troops.

Winner of the Battle of Dettingen: Pragmatic Army

British Regiments at the Battle of Dettingen: The following modern British Regiments hold Dettingen as a battle honour:

Third Troop of Horse Guards: Battle of Dettingen fought on 16th June 1743 in the War of the Austrian Succession: Mackenzie after Representation of Cloathing 1742

The Life Guards, the Blues and Royals, the Queen’s Dragoon Guards, the Royal Dragoon Guards, the Royal Scots Dragoon Guards, the Queen’s Royal Hussars, the Grenadier Guards, the Coldstream Guards, the Scots Guards,

the Princess of Wales’s Royal Regiment, the King’s Regiment, the Devon and Dorset Regiment, the Royal Anglian Regiment, the Light Infantry, the Royal Regiment of Fusiliers, the Royal Highland Fusiliers, the Royal Welch Fusiliers and the Duke of Wellington’s Regiment.

The following British regiments fought at the battle: 3rd and 4th Troops of Horse Guards, 2nd Troop of Horse Grenadier Guards, Royal Regiment of Horse, King’s Horse, 7th Horse, Royal Dragoons, Royal Scots Greys, King’s Dragoons, 4th, 6th and 7th Dragoons, 1st, 2nd and 3rd Foot Guards, 3rd, 4th, 11th, 12th, 13th, 20th, 21st, 23rd, 31st, 32nd, 33rd and 37th Foot.

Map of the Battle of Dettingen fought on 16th June 1743 in the War of the Austrian Succession: map by John Fawkes

Account of the Battle of Dettingen:

The Battle of Dettingen is a significant victory for the British Army, being the only time in modern history that a British Force has been led into battle by a reigning monarch, King George II.

Although ostensibly fighting to preserve Flanders from the predations of Louis XV’s French armies, the British army’s presence on the Continent from 1742 was as much to preserve the independence of Hanover, King George II being Elector of Hanover. The British force constituted part of what was known as the “Pragmatic Army”, comprising British, Austrian and Hanoverian troops.

Earl of Stair British Commander at the Battle of Dettingen fought on 16th June 1743 in the War of the Austrian Succession

In early 1743 the Pragmatic Allies were at a loss how to use their army against the French. Finally, late in the campaigning season and at King George II’s insistence, the Pragmatic Army march south to Frankfurt am Main and occupied the area to the east of Mainz on the River Main. King George II intended that the army’s presence should influence the election of the new Archbishop of Mainz, an elector in the Holy Roman Empire and therefore of importance in the affairs of Hanover.

The Pragmatic Army marched from Flanders during May 1743 and encamped near Aschaffenburg, around the village of Klein Ostheim. A large French Army under the Duc de Noailles occupied the south bank of the River Main to the west.

The Pragmatic generals were the Earl of Stair, in nominal overall command, the Duke D’Ahrenburg and Marshall Neipperg commanding the Austrians and General Ilton commanding the Hanoverian contingent.

On 8th June 1743, King George II, the King of England, joined the army, amid a flurry of celebrations and salutes. He brought with him a considerable retinue, conveyed by a long column of carriages and some 600 horses that paralysed the local roads for days, and his younger and favourite son, William Augustus, Duke of Cumberland, a major general in the British Army. Over the next few days George attended church services and functions in Mainz in anticipation of the election of the new archbishop.

The situation of the Pragmatic Army deteriorated dramatically when the French cut the route along the Rhine and Main Rivers by which the army received supplies from its Flanders base. There had been no proper supply of bread for a week, when finally on 16th June 1743 King George II ordered the retreat to begin; west along the road to Hanau and Frankfurt and then north to Flanders.

King George II with the Duke of Cumberland at the Battle of Dettingen on 16th June 1743 in the War of the Austrian Succession: picture by David Morier

The Pragmatic Army’s route lay along the north bank of the Main River. Within three miles, King George II’s army would pass through the village of Dettingen, where the road crossed several marshy brooks flowing into the Main.

As the Pragmatic Army marched towards Dettingen, advanced parties reported that the French occupied the village, blocking the road. During the night, the French, commanded by the Duc de Grammont, had crossed the river, using bridges of boats across the Main and held the village and the marshy ground between Dettingen and the hills in strength.

The presence of the French took the Pragmatic Army by surprise. It is a surprise that such a large force could have been in ignorance of the presence of the enemy on its own side of the river within five miles of its camp.

Preparing to give battle, the British, Austrian and Hanoverian troops formed line; the Main River on the left and the wooded Spessart Hills on the right. The Pragmatic Army took from 9am to midday to form up. This length of time must have been due to the lack of co-ordinated training between the regiments and national contingents and the difficulty of moving from a column of march with a considerable quantity of baggage into battle line.

No doubt there was great anxiety at the predicament in which the Pragmatic Army found itself.

The Duc de Noailles’ plan was, while the Duc de Grammont held the line of Dettingen and the streams preventing the Pragmatic allies from continuing their march, to hurry a section of his army along the south bank of the Main and cross at Aschaffenburg in the Pragmatic Army’s rear. The Pragmatic Allies would be caught between the two French forces and perhaps forced to surrender; King George II becoming a French prisoner.

Horse Grenadier of the Maison du Roi: Battle of Dettingen fought on 16th June 1743 in the War of the Austrian Succession

As the British regiments formed to face the French in Dettingen, they watched Noailles’ troops on the far bank marching east towards Aschaffenburg. After a hurried consultation the Pragmatic commanders dispatched the British and Hanoverian Foot Guards in haste back towards Aschaffenburg.

The French batteries on the south bank of the Main River began the battle, opening fire across the river as the marching French troops cleared their front. The bombardment was directed at the British cavalry moving along the North bank. The French fire seems to have inflicted few casualties.

It is said that de Grammont’s clear orders were to stay in Dettingen and force the Pragmatic Army to attack him. If this is so he disobeyed. As the British, Hanoverian and Austrian regiments completed their line the French advanced out of Dettingen to the attack.

There is little reliable information on the form of the battle or on the formation adopted by the Pragmatic troops. It would appear that British regiments were in the front line, but in what order is not clear. At an early stage, French cavalry, the Maison du Roi, charged the British cavalry by the river. The French were driven back, apparently with significant loss.

Dragoon Thomas Brown of Bland’s King’s Own Royal Dragoons: Battle of Dettingen fought on 16th June 1743 in the War of the Austrian Succession

The French assault bore all the hallmarks of extreme confusion, possibly a spontaneous and undisciplined advance that De Grammont did not order. The cavalry charge was followed by a French infantry attack on the Pragmatic line of foot, the French appearing to come out of Dettingen pell-mell and in some disorder.

King George II at the the Battle of Dettingen on 16th June 1743 in the War of the Austrian Succession: picture by Robert Hillingford

The French foot were repelled and, panic stricken, hurried back through Dettingen, re-crossing the Main by the bridges of boats. One of the bridges collapsed and many French troops are reputed to have been drowned.

Bland’s King’s Own Royal Dragoons: Battle of Dettingen fought on 16th June 1743 in the War of the Austrian Succession: picture by Harry Payne

No attempt seems to have been made to follow up the repulse of De Grammont’s force. In due course the Pragmatic Army resumed its march and continued its way to Hanau, passing within a half mile or so of the chaos at the French bridges of boats.

The British Army had not been in a major continental war for twenty-five years. There were few officers or soldiers with significant fighting experience, other than some older officers who had fought with Marlborough, such as the Earl of Stair and, curiously, King George II himself who had fought with distinction leading the Hanoverian contingent at the Battle of Oudenarde in 1708.

Contemporary authorities show the lack of military training systems in the British Army, particularly for the mounted regiments. There are clear references in the authorities to British cavalry regiments (particularly the King’s Horse and the Blues) bolting through the British infantry line during the battle, primarily due to inadequate horsemanship.

Contemporary map of the Battle of Dettingen on 16th June 1743 in the War of the Austrian Succession by Andreas Reinhard (II) of Frankfurt am Main from the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam. The map is orientated with north to the bottom. The extensive French batteries to the south of the River Main are shown

Casualties at the Battle of Dettingen:

British: 15 officers, 250 soldiers and 327 horses killed. 38 officers, 520 soldiers and 155 horses wounded.

It is hard to reconcile the low British casualties with the bombardment by 50 French guns across the river into the British flank, a couple of hundred metres away at most, at the beginning of the battle. It may be that the guns were masked for longer by the passing French troops than the descriptions of the battle indicate.

Hanover: 177 killed and 376 wounded.

Austria: 315 killed and 663 wounded.

French casualties: 8,000 (not a reliable figure but the best available)

Follow-up to the Battle of Dettingen:

Royal Regiment of Horse (Blues): Battle of Dettingen fought on 16th June 1743 in the War of the Austrian Succession: Mackenzie after Representation of Cloathing 1742

Once the battle was over, the Pragmatic Army continued its retreat to Hanau and in due course returned to its bases in Flanders. The British casualties were left on the battlefield for the French to look after.

Regimental anecdotes and traditions from the Battle of Dettingen:

- At the beginning of the battle it seemed that the French threat was to Aschaffenburg. The Hanoverian General Ilton dispatched the Hanoverian and British Foot Guards to the rear of the army. To their indignation these regiments took no part in the battle, for which they blamed Ilton. There was no love lost between the British and the Hanoverians. General Ilton protested that his action in sending them to the rear had ‘preserved’ them. The officers of the Foot Guards labeled Ilton the ‘Confectioner’.

- The absence of the British Foot Guards from the fighting was a cause of much ribaldry among the British Line Regiments. There was an incident during the First World War when a battalion of the East Surrey Regiment (31st Foot the ‘Young Buffs) made slighting remarks at a Grenadier Guards battalion of their failure to take part in the fighting at the Battle of Dettingen.

- One of the principal French regiments of foot in the attack from Dettingen was the Garde Française. This regiment is reputed to have been particularly quick to re-cross the Main, many of its soldiers being thrown into the river by the bridge’s collapse. The regiment thereby acquired the nickname of “Les Canards du Main”. Hence the French word ‘canard’ meaning an insult. (see the comments of Sir Charles Hay to the Garde Française at the Battle of Fontenoy).

- During the attack by the French Maison du Roi, Cornet Richardson of Ligonier’s Horse (7th Dragoon Guards) rescued his regiment’s standard.

- Dragoon Thomas Brown rescued the guidon of Bland’s Dragoons (3rd Hussars) and was knighted by King George II.

- Another cavalryman who distinguished himself at the Battle of Dettingen was George Daraugh of Sir Robert Rich’s Dragoons.

- Lieutenant Colonel Sir Andrew Agnew of Lochaw warned his Royal Scots Fusiliers not to fire until they could ‘see the whites of their e’en’.

- King George II is said to have called the 31st Foot the “Buffs” during the battle. It was pointed out to him that they were not in fact the “Buffs”, although they wore buff facings like the 3rd Foot, but were a more recently raised regiment. The King is reputed to have called out, “Well done the Young Buffs.”

- The Horse Guards are said to have played ‘Britons strike home’ as they charged.

- The Duke of Cumberland was wounded by a bullet in the leg during the battle. He was troubled by this injury for the rest of his life. His close friend the Earl of Albemarle was also wounded (see Braddock III).

- King George II’s horse bolted during the battle. The King is said to have sheltered under an oak and to have presented an oak leaf to the soldiers who looked after him. The Cheshire Regiment (22nd Regiment of Foot) claims this honour. However they were in garrison in Gibraltar at the time.

- King George II was not the only one who had trouble controlling his horse. The Royal Regiment of Horse (the Blues) and the King’s Horse are reputed to have bolted through the Royal Scots Fusiliers.

- Among those who took part in the Battle of Dettingen were:

- George August Elliott, the defender of Gibraltar during the 7 year siege in the Bourbon War of 1777, becoming Lord Heathfield,

- Lieutenant James Wolfe, appointed in 1759 Major General in America and capturer of the City of Quebec,

- Lieutenant Jeffrey Amherst, appointed in 1759 to command in America and conqueror of French Canada.

- The Battle of Dettingen is of considerable importance in British history almost solely because of the presence of the Sovereign, King George II. Handel wrote a Te Deum and an anthem in celebration of the victory.

-

31st Foot: Battle of Dettingen fought on 16th June 1743 in the War of the Austrian Succession: Mackenzie after Representation of Cloathing 1742

King George II is said to have revived the title of ‘Knight Banneret’ to honour British soldiers for distinguished conduct at the Battle of Dettingen. Among those said to have been so honoured were Cornet Richardson of the 7th Horse and Dragoon Thomas Brown of Bland’s King’s Own Dragoons.

- Lieutenant-General John Ligonier was made a Knight of the Bath by King George II on the field after the Battle of Dettingen.

- The contemporary plan of the Battle of Dettingen (see above) from the archives of the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam is a significant document in establishing the circumstances and chain of events in the battle. It shows for example that the French camp was immediately across the Main River from the camp of the Pragmatic Army. It also shows the extensive French batteries on the south side of the River Main.

References for the Battle of Dettingen:

- William Augustus Duke of Cumberland by Evan Charteris

- Field Marshall Lord Ligonier by Rex Whitworth

- Fortescue’s History of the British Army Volume II

- Fontenoy by Francis Henry Skrine

- William Augustus Duke of Cumberland by Rex Whitworth

- Dettingen 1743 by Michael Orr

The previous battle in the British Battles series is the Battle of Malplaquet

The next battle of the War of the Austrian Succession is the Battle of Fontenoy

To the War of the Austrian Succession index

King George II at the Battle of Dettingen on 16th June 1743 in the War of the Austrian Succession as his Horse Guards charge the French Maison du Roi