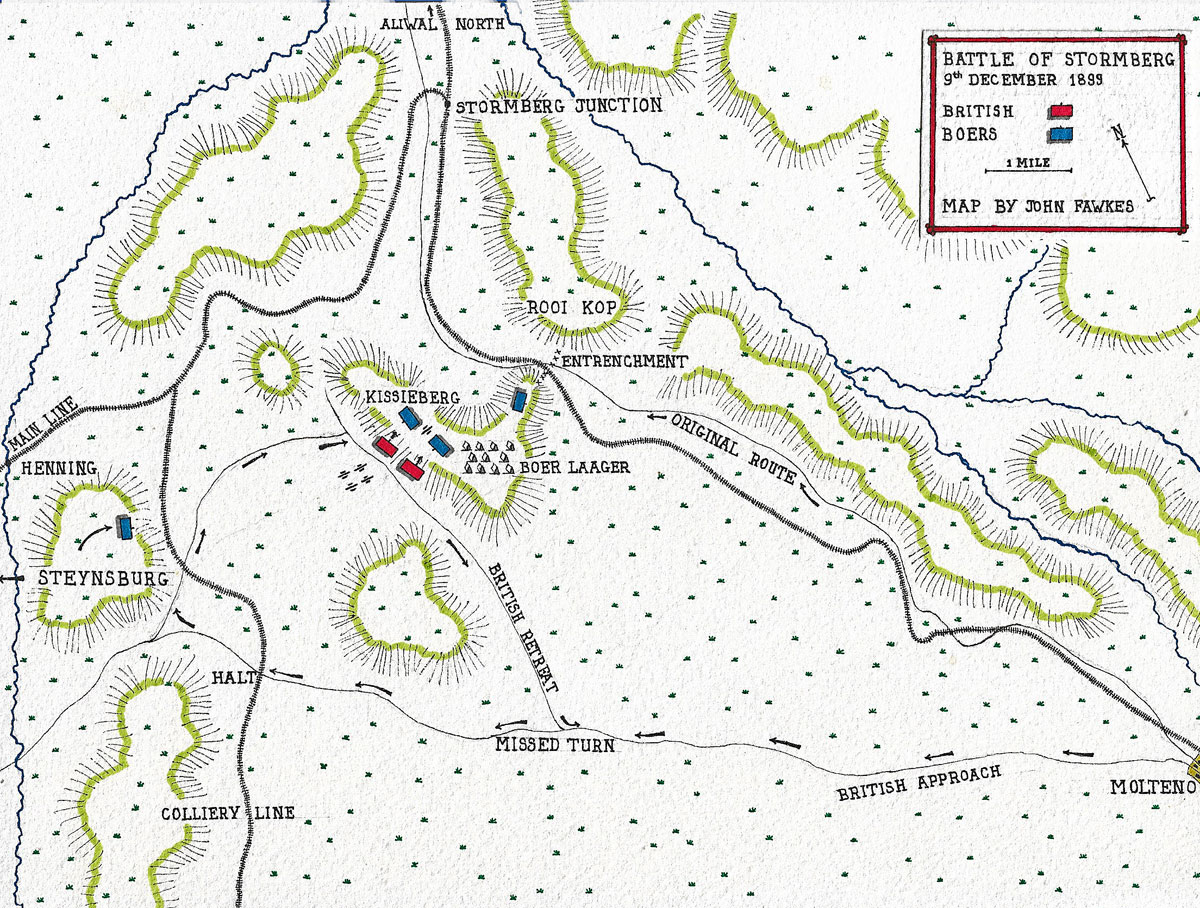

General Gatacre’s disastrous defeat in Northern Cape Colony, fought on 9th/10th December 1899; the first battle of ‘Black Week’

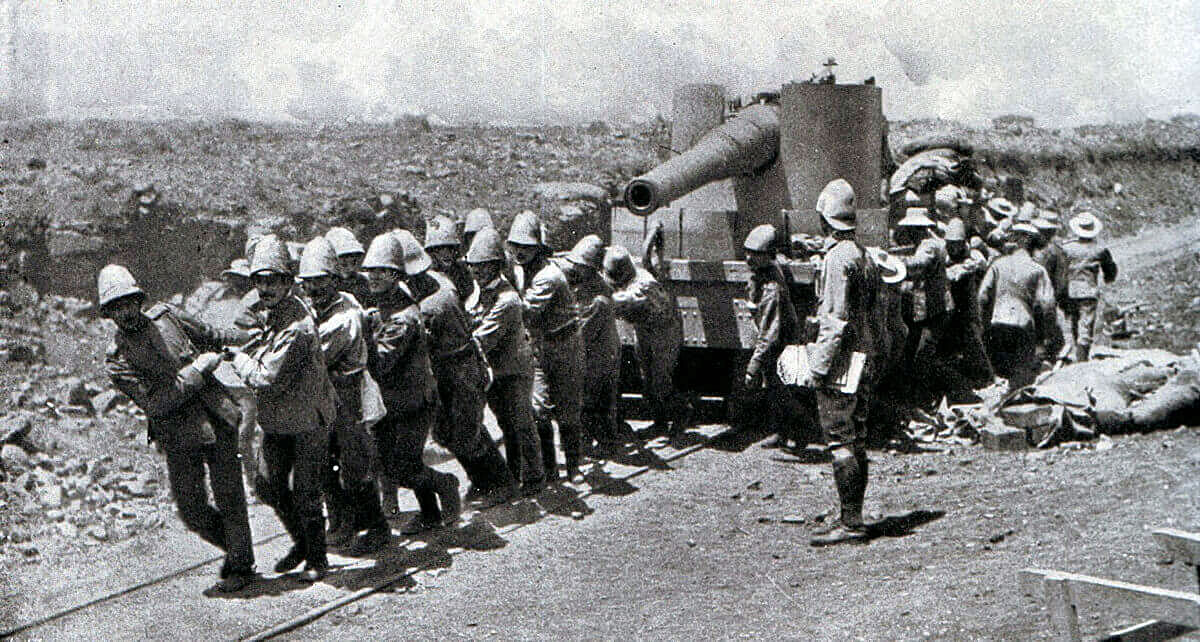

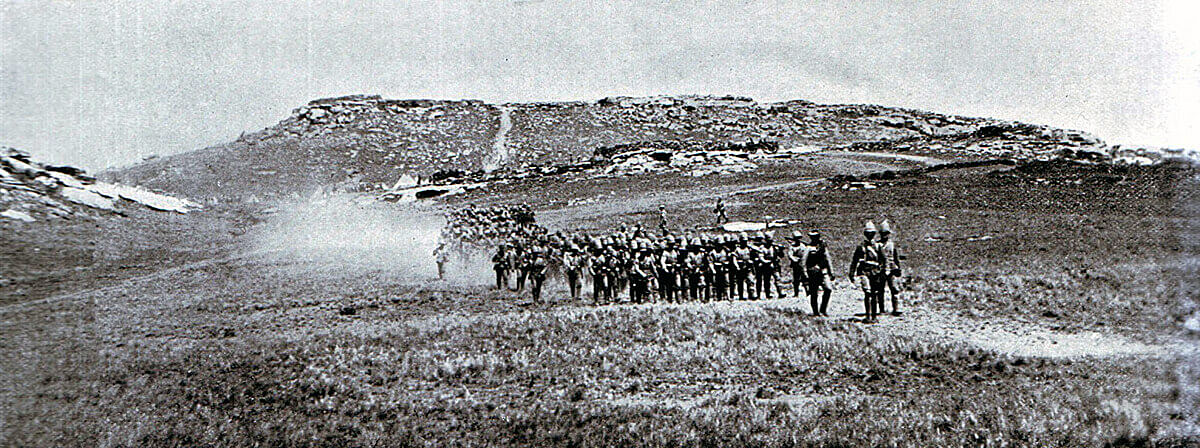

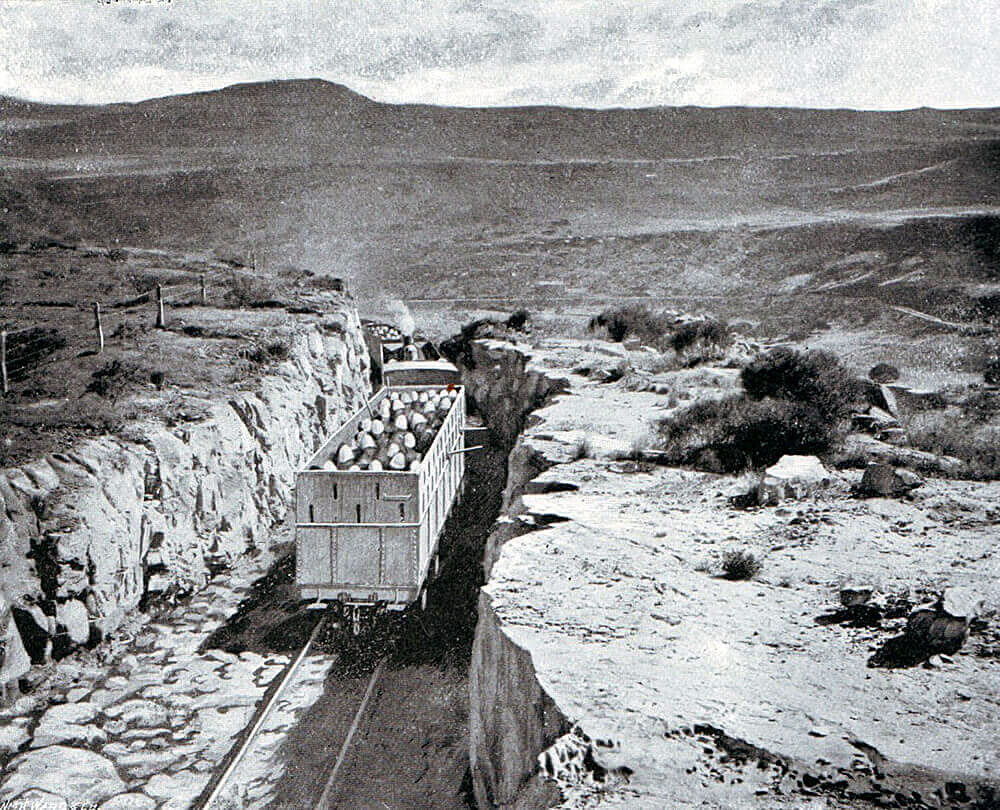

British troops hauling a gun up the railway line: Battle of Stormberg 9th/10th December 1899 in the Boer War

63. Podcast on the Battle of Stormberg: General Gatacre’s disastrous defeat in Northern Cape Colony, fought on 9th/10th December 1899 in the Boer War; the first battle of ‘Black Week’: John Mackenzie’s britishbattles.com podcasts

63. Podcast on the Battle of Stormberg: General Gatacre’s disastrous defeat in Northern Cape Colony, fought on 9th/10th December 1899 in the Boer War; the first battle of ‘Black Week’: John Mackenzie’s britishbattles.com podcasts

The previous battle in the Boer War is the Battle of Modder River

The next battle in the Boer War is the Battle of Magersfontein

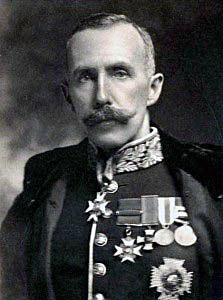

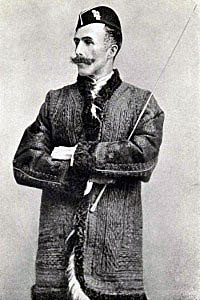

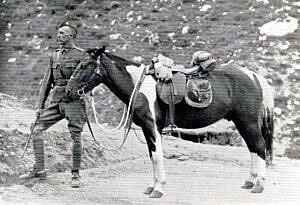

Lieutenant General Sir William Gatacre the British commander at the Battle of Stormberg on 9th/10th December 1899 in the Boer War

War: The Boer War

Date: 9th and 10th December 1899

Place: Stormberg Valley in the Eastern Cape Colony, South Africa.

Combatants : British against the Boers

Generals: Lieutenant General Sir William Gatacre against General Olivier.

Size of the armies: 2,600 British against 1,700 Boers.

Arms and equipment: The Boer War was a serious jolt for the British Army. At the outbreak of the war British tactics were appropriate for the use of single shot firearms, fired in volleys controlled by company and battalion officers; the troops fighting in close order. The need for tight formations had been emphasised time and again in colonial fighting. In the Zulu and Sudan Wars overwhelming enemy numbers armed principally with stabbing weapons were kept at a distance by such tactics, but, as at Isandlwana, would overrun a loosely formed force. These tactics had to be entirely rethought in battle against the Boers armed with modern weapons.

In the months before hostilities the Boer commandant general, General Joubert, bought 30,000 Mauser magazine rifles, firing smokeless ammunition, and a number of modern field guns and automatic weapons from the German armaments manufacturer Krupp, the French firm Creusot and the British company Maxim. Unfortunately for the Boers they chose to buy high explosive ammunition for their new field guns. The war was to show that high explosive was largely ineffective in the field, unless rounds landed on rocky terrain and splintered the rock. The British artillery relied upon air-bursting shrapnel which was highly effective against infantry in open country.

There were many reports of Boer ammunition failing to explode. It seems likely that this will have been due to a lack of training for the Boer gunners in the use of shells which needed to be fused before firing.

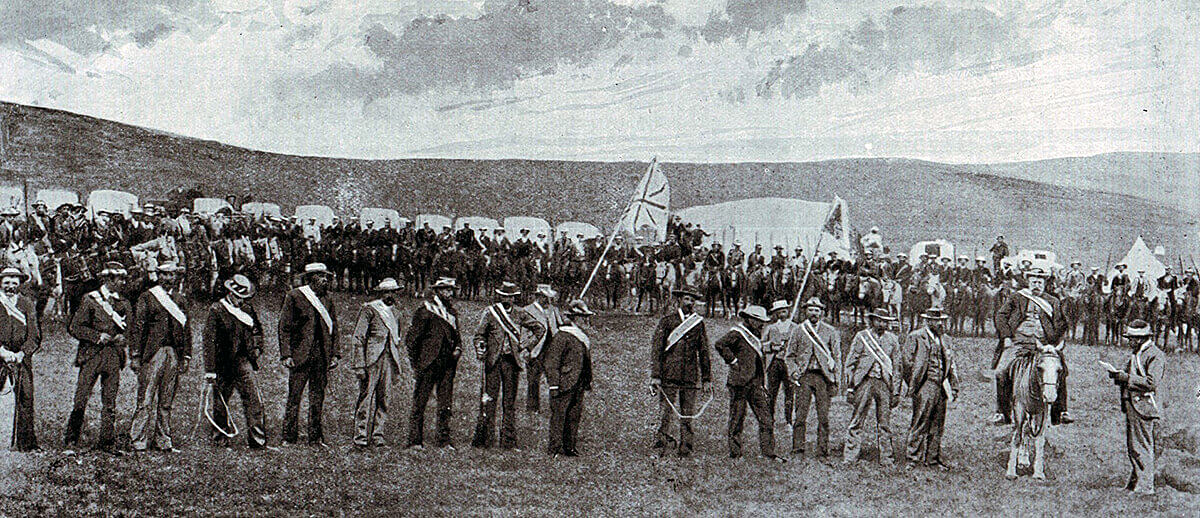

Boer Wapenschouwing or shooting competition before the South African War: Battle of Stormberg 9th/10th December 1899 in the Boer War

Once the war was under way the arms markets of Europe were closed to the Boers, due to the British naval blockade, and the error in ammunition selection could not be remedied.

The Boer commandoes, without formal discipline, welded into a fighting force through a strong sense of community and dislike for the British. Field Cornets led burghers by personal influence not through any military code. The Boers did not adopt military formation in battle, instinctively fighting from whatever cover there might be. Most Boers were countrymen, running their farms from the back of a pony with a rifle in one hand. These rural Boers brought a life time of marksmanship to the war, an important advantage further exploited by Joubert’s consignment of smokeless magazine rifles. Viljoen is said to have coined the aphorism “Through God and the Mauser”. With strong field craft skills and high mobility the Boers were natural mounted infantry. The urban burghers and foreign volunteers readily adopted the fighting methods of the rest of the army.

Other than in the regular uniformed Staats Artillery and police units, the Boers wore their every day civilian clothes on campaign.

After the first month the Boers lost their numerical superiority, spending the rest of the formal war on the strategic defensive against British forces that outnumbered them, although operating with aggression when led by the younger generation of leaders like De Wet.

British tactics, developed on the North-West Frontier of India, Zululand, the Sudan and in other colonial wars against badly armed tribesmen, when used at Modder River, Magersfontein, Colenso and Spion Kop were inappropriate against entrenched troops armed with modern magazine rifles. Every British commander made the same mistake; Buller, Methuen, Roberts and Kitchener (Elandslaagte was a notable exception where Hamilton specifically directed his infantry to keep an open formation). When General Kelly-Kenny attempted to winkle Cronje’s commandoes out of their riverside entrenchments at Paardeburg using his artillery, Kitchener intervened and insisted on a battle of infantry assaults, with the same expensive consequences as earlier in the war.

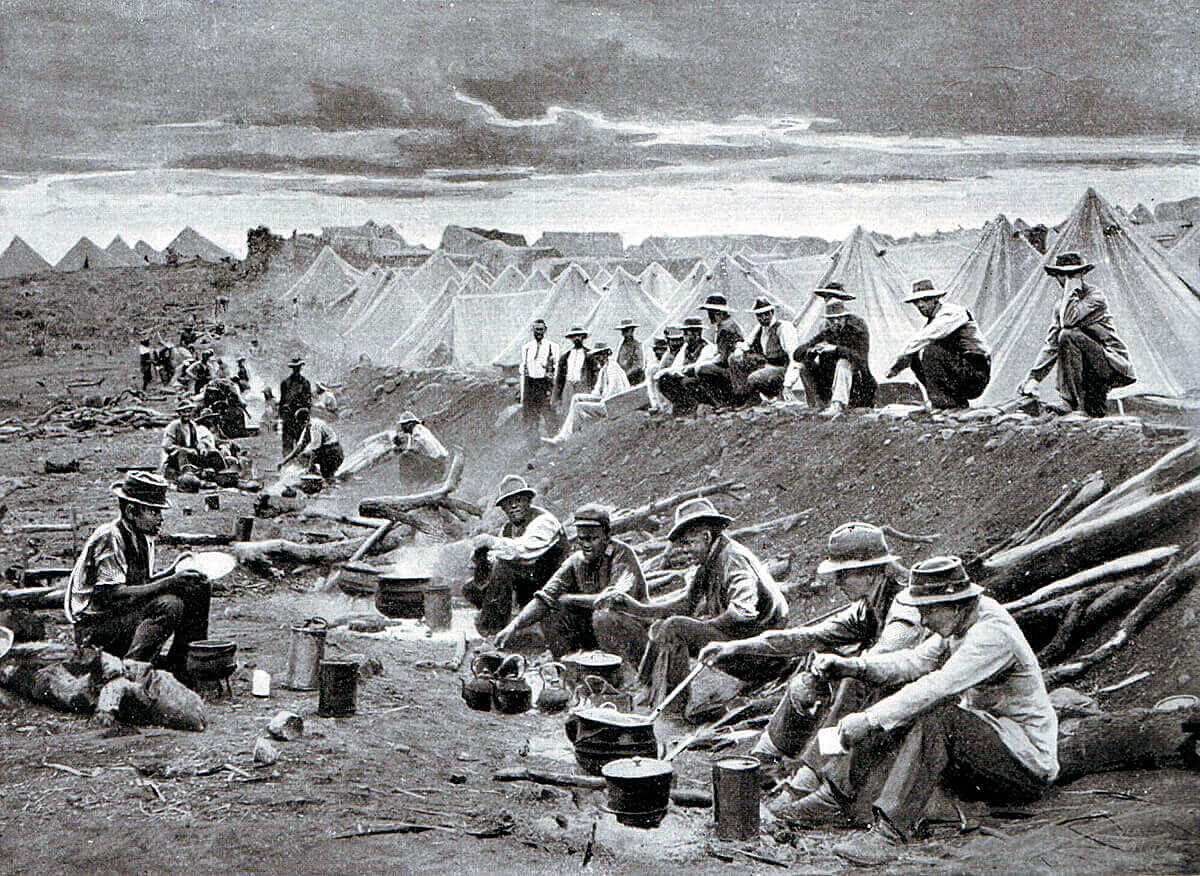

Boer laager or encampment during the South African or Boer War: Battle of Stormberg 9th/10th December 1899 in the Boer War

The British Army was not the only European Army to fail to appreciate the effect of long range magazine fed rifle fire. The Germans and the French in the opening months of the First World War made massed infantry attacks in the face of such fire, suffering enormous casualties, as did the Russians and Austro-Hungarians.

Some of the most successful British and Empire troops in the South African War were the non-regular regiments; the Imperial Light Horse, City Imperial Volunteers, the South Africans, Canadians, Australians and New Zealanders, who more easily broke from the habit of earlier British colonial warfare, using their horses for rapid movement rather than the charge, advancing by fire and manoeuvre in loose formations and making use of cover, rather than the formal advance into a storm of Mauser bullets.

War Aims of the Boers in the South African War:

Having started the hostilities the Boers found themselves without an achievable war aim. The only strategy that might have had a chance of success would have been to invade and occupy the whole of Cape Colony, Natal and the other neighbouring British colonies. The two Boer republics did not have the resources to carry out such an extensive operation. In any case they could not have prevented a British sea landing to retake these areas.

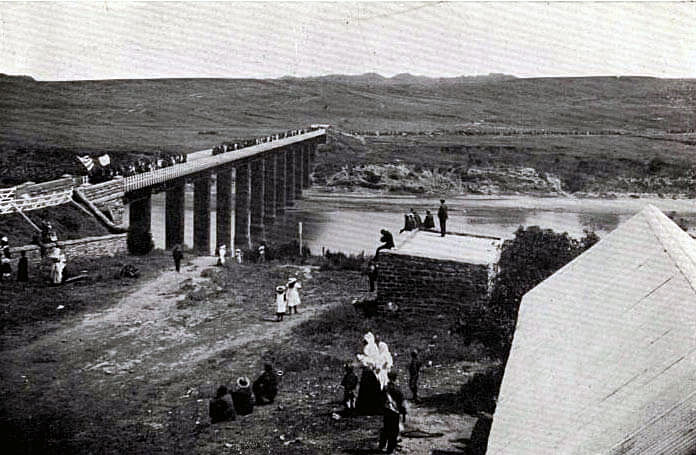

Boers crossing the bridge over the Orange River at Aliwal North before advancing south to Stormberg before the Battle of Stormberg on 9th/10th December 1899 in the Boer War

Once war was declared the Boers invaded and occupied Natal as far as the Tugela River, but with Ladysmith holding out in their rear. The Orange Free State government was not prepared to allow its forces to advance further south in Natal. In Cape Colony some of the citizens of Boer origins joined their brothers from the two Republics but most did not.

The only other offensive operations the Boers carried out were to besiege Mafeking in the north and Kimberley further south on the Cape Colony border. Both sieges were unsuccessful. A limited incursion was carried out into the central area of Cape Colony up to the area around Stormberg, leading to Gatacre’s disastrous counter-attack.

Conan Doyle, who served as a doctor in South Africa during the war, reports that the Boers missed an opportunity at the beginning of the war to invade Cape Colony and capture the substantial quantity of stores built up at places like De Aar.

A major difficulty for the Boer armies was that although competent in defence, digging field fortifications and using their magazine rifles to great effect to defend them, the Boers lacked an effective tactical offensive capability. The absence of formal military discipline made it difficult for the Boer commanders to devise strategies they could rely on their troops to carry through. As the British built up their armies and began to advance defeat for the Boers became inevitable.

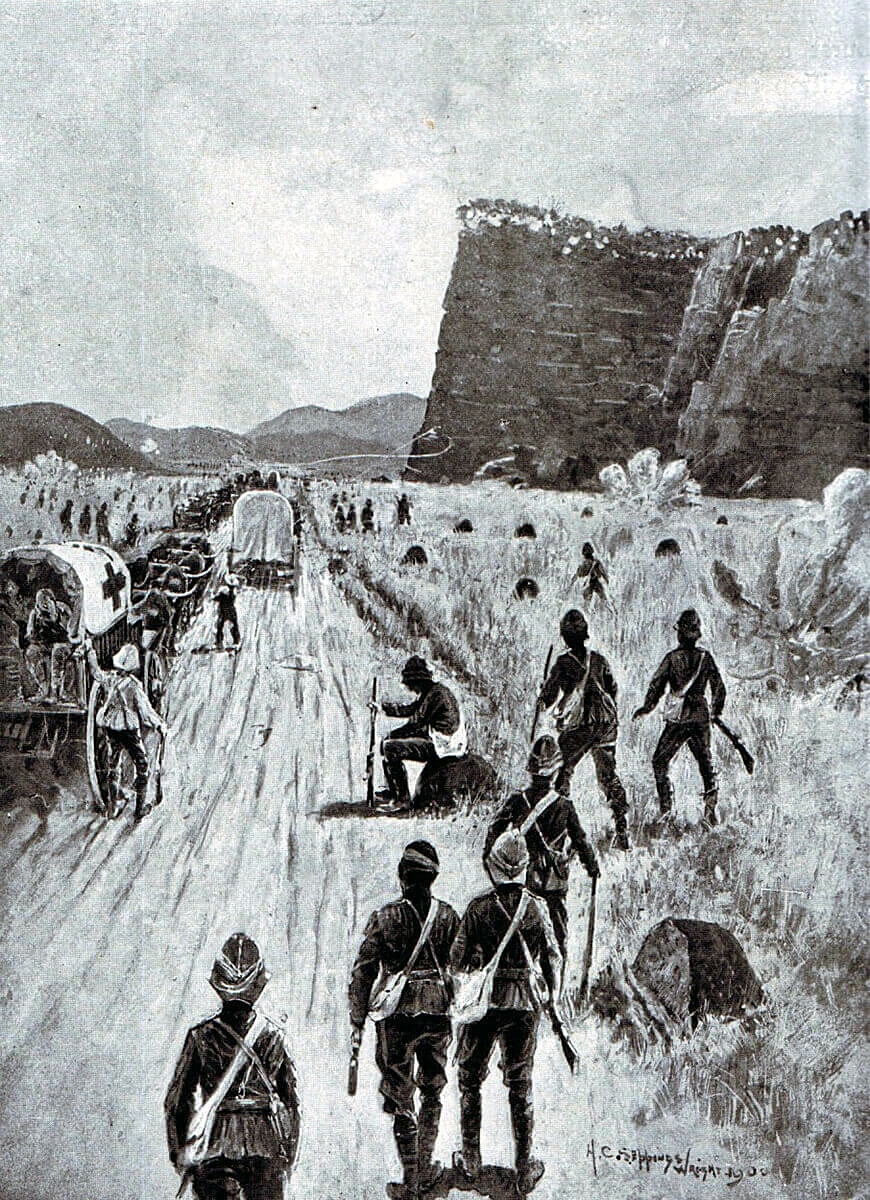

Stormberg Pass near to the scene of the Battle of Stormberg on 9th/10th December 1899 in the Boer War: picture by H.C. Seppings Wright

The Boer armies suffered from a wide variation in competence and commitment. The general belief was that the Transvaalers were more resilient and determined fighters than the Free Staters. The younger Boer commanders tended to be more resourceful and aggressive and felt handicapped by the older more senior commanders.

The British regiments made an uncertain change into khaki uniforms in the years preceding the Boer War, with the topee helmet as tropical headgear. Highland regiments in Natal devised aprons to conceal coloured kilts and sporrans. By the end of the war the uniform of choice was a slouch hat, drab tunic and trousers. The danger of shiny buttons and too ostentatious emblems of rank was emphasised in several engagements with disproportionately high officer casualties. Officers quickly took to carrying rifles like their men and abandoned swords and other obvious emblems of rank.

The British infantry was armed with the Lee Metford magazine rifle firing 10 rounds, but no training regime had been established to take advantage of the accuracy and speed of fire of the weapon. Personal skills such as scouting and field craft were little taught. The idea of fire and movement on the battlefield was largely unknown, many regiments still going into action in close order. Notoriously General Hart insisted that his Irish Brigade fight shoulder to shoulder as if on parade in Aldershot. Short of regular troops, Britain engaged volunteer forces from Britain, Canada, Australia and New Zealand who brought new ideas and more imaginative formations to the battlefield.

The war was littered with incidents in which British contingents became lost or were ambushed often unnecessarily and forced to surrender. The war was followed by a complete re-organisation of the British Army, with emphasis placed on personal weapon skills and fire and movement using cover.

Northumberland Fusiliers in 1901. The Sergeant is wearing the Queen’s South Africa Medal and the King’s South Africa Medal: Battle of Stormberg 9th/10th December 1899 in the Boer War

The British artillery was a powerful force in the field, underused by commanders with little training in the use of modern guns in battle. Pakenham cites Pieters as being the battle at which a British commander, surprisingly Buller, developed a modern form of battlefield tactics: heavy artillery bombardments co-ordinated to permit the infantry to advance under their protection. It was the only occasion that Buller showed any real generalship and the short inspiration quickly died.

The Royal Field Artillery fought with 15 pounder rifled breach loading guns, the Royal Horse Artillery with 12 pounders and the Royal Garrison Artillery batteries with 5 inch howitzers. The Royal Navy provided heavy field artillery with a number of 4.7 inch naval guns mounted on field carriages devised by Captain Percy Scott of HMS Terrible and the iconic long 12 pounders, seen in the Royal Navy gun competitions at the Royal Tournament.

Maxim automatic weapons were used by the British, often mounted on special carriages, accompanying the mounted infantry, cavalry and infantry battalions, one on issue to each unit.

Winner of the Battle of Stormberg: The Boers

British Regiments at the Battle of Stormberg:

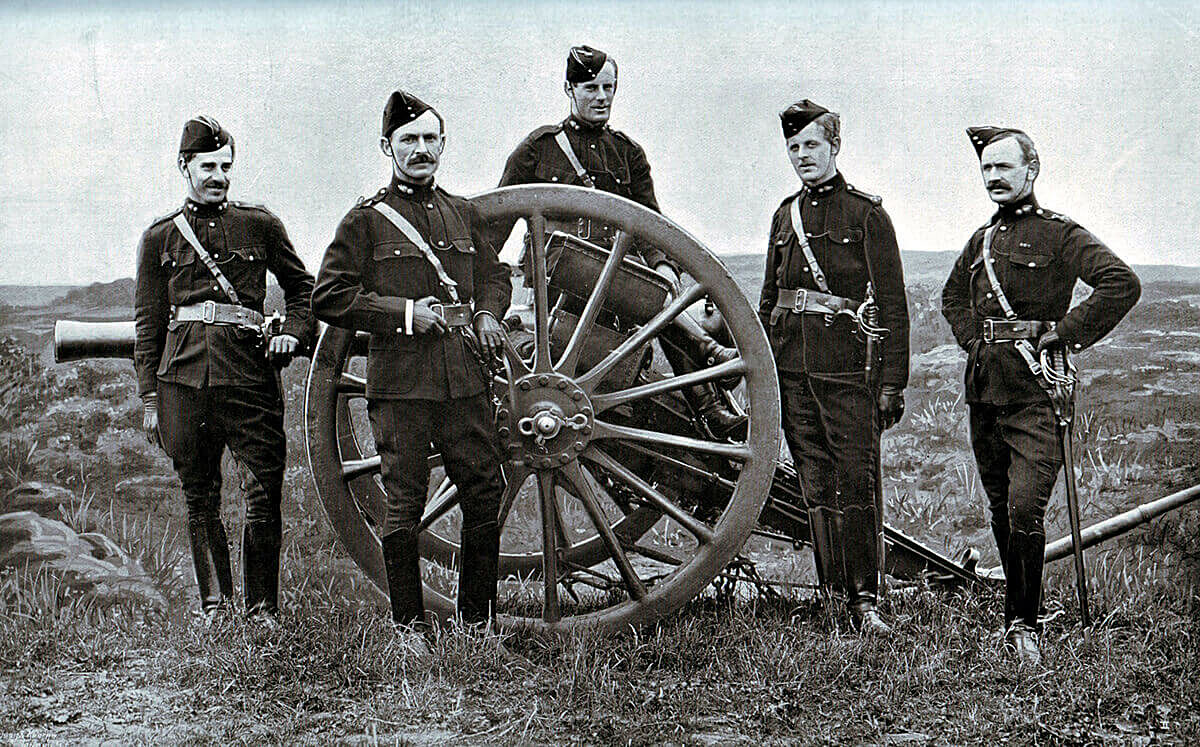

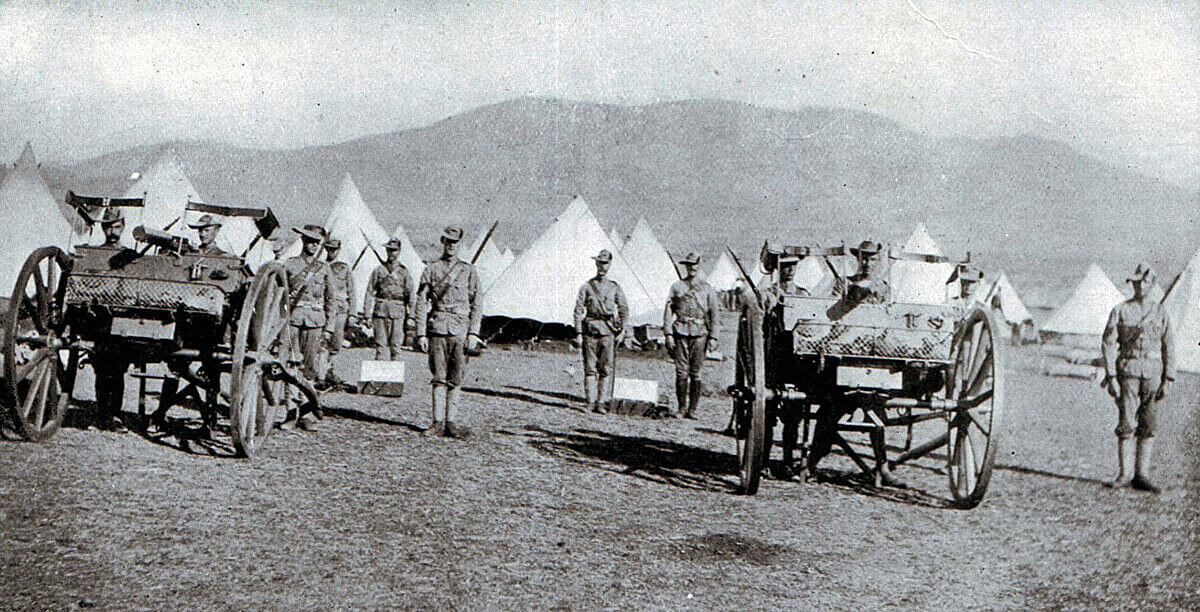

Royal Field Artillery: 74th and 77th Batteries

33rd Company (part) Royal Engineers:

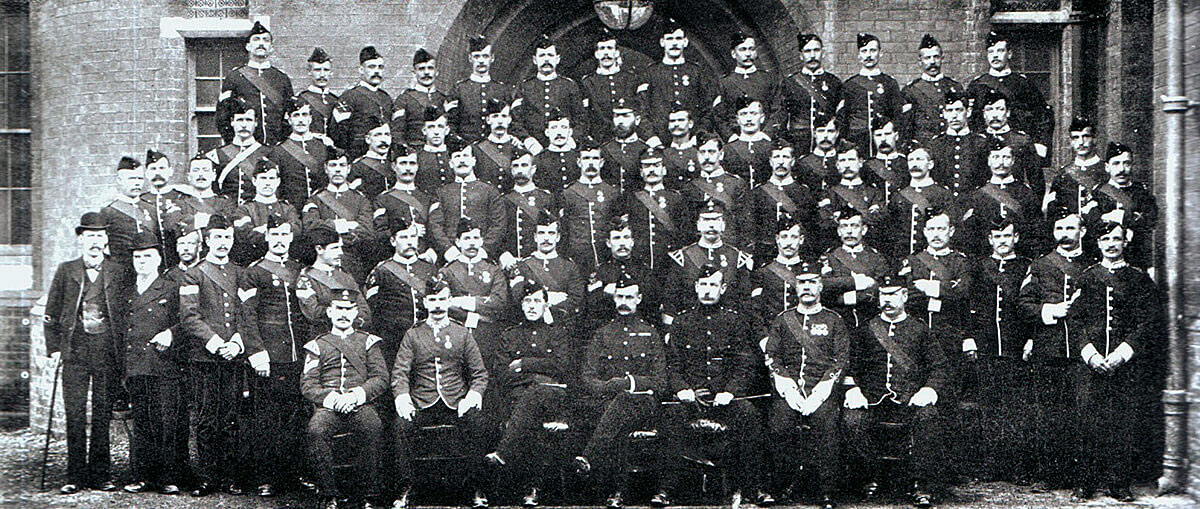

2nd Northumberland Fusiliers, now the Royal Regiment of Fusiliers

1st Royal Berkshire Regiment, later the Duke of Edinburgh’s Royal Regiment, then the Royal Gloucestershire, Berkshire and Wiltshire Regiment and now part of the Rifles

2nd Royal Irish Rifles, later the Royal Ulster Rifles and now the Royal Irish Regiment

Mounted Infantry

Officers of 77th Field Battery Royal Field Artillery, one of Gatacre’s batteries at the Battle of Stormberg on 9th/10th December 1899 in the Boer War, standing by one of the battery’s 15 pounder field guns

Background:

The two Boer Republics, the Transvaal and the Orange Free State, began the war against Great Britain on 14th October 1899. Their principal operation was to invade Natal. They also began sieges of Mafeking and Kimberley, both important towns along the western borders of the two Boer republics, and the Boers in the Orange Free State invaded across the Orange River into Cape Colony.

The Government in Great Britain sent an Army Corps to South Africa under the command of Lieutenant General Sir Redvers Buller.

The three battles in Natal, Talana Hill on 20th October, Elandslaagte on 21st October and Ladysmith on 30th October 1899 saw the British force in Northern Natal under Lieutenant General Sir George White penned up in Ladysmith and put under siege by the Boers.

Buller arrived in South Africa and prepared his strategy for the war. Lieutenant General Lord Methuen would command the force, comprising the 1st Division, with the task of marching up the railway running north along the western border of the Boer Republics to relieve Kimberley. Lieutenant General Gatacre would conduct a holding operation in the Eastern Cape Colony, while General French carried out the same role in Western Cape Colony.

Sir George White, the British commander-in-chief in Natal, was under siege in Ladysmith so a general fell to be appointed to command the relief force in Natal. Buller took this role on himself, leaving the overall strategy of the war with no direct guiding hand.

Boers in position on a mountain as at the Battle of Stormberg on 9th/10th December 1899 in the Boer War: picture by F.J. Waugh

Buller expected it would take him two weeks to relieve the Ladysmith garrison, after which he would return to Cape Colony. Buller was to spend the rest of the active war crossing the Tugela River and breaking the siege of Ladysmith.

In early 1900 the British government sent a strong command team of Lord Roberts and General Kitchener to take over the offensive in the Orange Free State from Cape Colony. In the meantime Lord Methuen was left to command the only advance on the Boer Republics, while General Gatacre was left to deal with the Boer incursion in the Eastern Cape.

Lieutenant General Sir William Gatacre:

In 1899 Major General (local Lieutenant General) Sir William Gatacre was one of the British Army’s rising stars. The Battle of Stormberg ruthlessly eclipsed this star.

Gatacre was commissioned into the 77th Regiment (later 2nd Middlesex Regiment) in 1862 and went to India with his regiment. He was promoted major in 1881 and lieutenant colonel commanding an infantry battalion in1884.

Gatacre took part in the operations in Upper Burma in1887/8, was mentioned in dispatches and awarded the DSO. He then occupied a number of appointments in India.

In 1886/7 Gatacre had charge of the plague relief in Bombay, for which he was decorated. Gatacre showed his intellectual abilities by producing a substantial report, used in subsequent plague operations.

In 1888 Gatacre held a staff appointment in the Hazara Expedition on the North-West Frontier of India.

In 1895 Gatacre commanded the 3rd Brigade in the Chitral Relief Force on the North-West Frontier. Increasingly concerned as to the fate of the besieged Anglo-Indian garrison in Chitral Fort, Sir Robert Low, commanding the relief column, sent Gatacre on with a small force, confident that Gatacre would push forward with an energy not to be expected from other senior officers. Gatacre did not disappoint, forging across the mountains and re-building collapsed roads where necessary. Gatacre thereby confirmed his reputation as a senior officer of resource, determination and unrivalled energy.

In 1896 Gatacre returned to Britain to command a brigade at Aldershot.

When Kitchener led the British operation to recover the Sudan for the Egyptian Khedive in 1897, Gatacre was given command of the British Brigade, leading it at the Battle of Atbara, spectacularly cutting through the Dervish thorn wall at the head of his troops, and then the British Division in 1899, leading it at the Battle of Omdurman.

Omdurman was one of the landmark battles of British military history. Presence at Omdurman opened doors in the British military hierarchy and few did better than Gatacre, who was knighted, KCB, and promoted major general.

General Gatacre on the road to Chitral during the operations to relieve the Anglo-Indian garrison on the North-West Frontier of India in 1895: Battle of Stormberg 9th/10th December 1899 in the Boer War

Winston Churchill encountered Gatacre in the Sudan and knew of his reputation in India and South Africa. Churchill wrote of Gatacre in ‘River War’, his account of Kitchener’s reconquest of the Sudan in 1897/9 published in the same year before the South African War began: ‘The officer selected for the command of the British brigade [in the Sudan in 1897] was a man of high character and ability. General Gatacre had already led a brigade in the Chitral expedition, and, serving under Sir Robert Low and Sir Bindon Blood had gained so good a reputation that after the storming of the Malakand Pass and the subsequent action in the plain of Khar it was thought desirable to transpose his brigade with that of General Kinloch, and send Gatacre forward to Chitral. From the mountains of the North-West Frontier the general was ordered to Bombay, and in a stubborn struggle with the bubonic plague, which was then at its height, he turned his attention from camps of war to camps of segregation. He left India, leaving behind him golden opinions, just before the outbreak of the great Frontier rising, and was appointed to a brigade at Aldershot. Thence we now find him hurried to the Soudan—a spare, middle-sized man, of great physical strength and energy, of marked capacity and unquestioned courage, but disturbed by a restless irritation, to which even the most inordinate activity afforded little relief, and which often left him the exhausted victim of his own vitality.’

Gurkhas crossing the Lowrai Pass during General Gatacre’s dash to relieve the garrison of Chitral Fort on the North-West Frontier of India in 1895: Battle of Stormberg on 9th/10th December 1899 in the Boer War

Writing after Gatacre’s dismissal from command in his book on the South African War ‘London to Ladysmith via Pretoria’ published in 1900 Winston Churchill described Gatacre as ‘brave and capable’.

Sir George Robertson of the Indian Medical Service, the commander of the besieged Chitral Fort garrison, wrote of Gatacre in his book ‘Chitral The Story of a Minor Siege’: “He [Gatacre] is a man whose exploits, based on an almost superhuman energy and power of endurance, may someday become fabulous. After making a record, he sets himself to break it as a point of honour…” Robertson wrote with considerable gratitude for Gatacre’s efforts to relieve the garrison, thrusting over the mountains in the most distant reaches of British India with a small force and limited supplies amongst hostile tribes.

General Gatacre giving the signal to cease firing at the end of the Battle of Omdurman in 1898: Battle of Stormberg on 9th/10th December 1899 in the Boer War

Gatacre described with some pride attending the Governor-General’s Ball in India in the 1880s, leaving at one am and riding two hundred miles on relays of horses arranged in advance to ensure he was at his desk at the usual time that morning.

In reference to the South African War Churchill makes the comment that Gatacre had to learn the lesson of fighting against Europeans armed with magazine fed rifles in common with British officers of all ranks.

William Forbes Gatacre as a colonel in India in 1888: Battle of Stormberg 9th/10th December 1899 in the Boer War

Gatacre’s driving passions were to ensure that he and his soldiers were fit for battle and to get at the enemy.

Account of the Battle of Stormberg:

General Buller arrived in South Africa at Cape Town in early November 1899 with the 1st Army Corps, the British army hurriedly assembled to fight the Boers, in which General Sir William Gatacre commanded the 3rd Division, comprising eight infantry battalions with supporting arms.

Buller’s immediate priorities were to stem the invasion of Natal and to relieve Kimberley to prevent the diamond resource falling into Boer hands.

In the Eastern Cape a Boer force commanded by General Olivier was advancing south down the East London railway towards Stormberg and further east towards Dordrecht.

Buller took the lion’s share of the Army Corps to Natal, leaving Methuen with a force to march up the western railway to relieve Kimberley, while Gatacre was given the unenviable task of stemming the central Boer invasion of Cape Colony with the smallest possible force.

General Gatacre’s camp at Queenstown prior to the operation leading to the Battle of Stormberg on 9th/10th December 1899 in the Boer War

General Gatacre arrived at Queenstown on the south to north railway line from East London on the southern coast to Aliwal North on the Orange Free State border on 18th November 1899. Instead of the eight infantry battalions of the 3rd Division with supporting artillery and other arms, Gatacre was accompanied by one battalion, the 2nd Royal Irish Rifles. He found he had in addition those units of the local garrison, part of 1st Berkshire Regiment, a detachment of Royal Garrison Artillery, a half company of Royal Engineers, 230 men of the Frontier Mounted Rifles and 285 men of the Queenstown Rifle Volunteers, the local defence unit. The Frontier Mounted Rifles possessed five mountain guns and maxim machine guns.

From his arrival at Queenstown Gatacre worked to raise local units and bring his troops to a good level of fitness and training. At the same time he conducted extensive reconnaissance of the ground leading to the Boer positions.

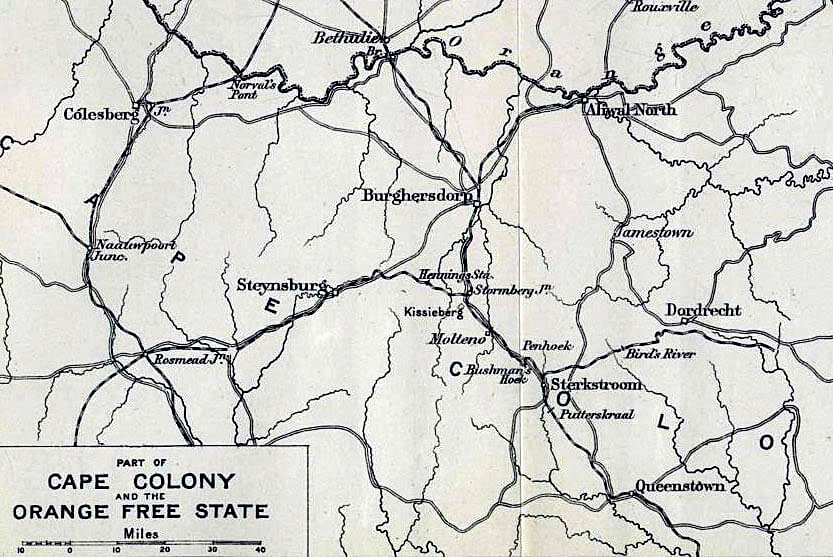

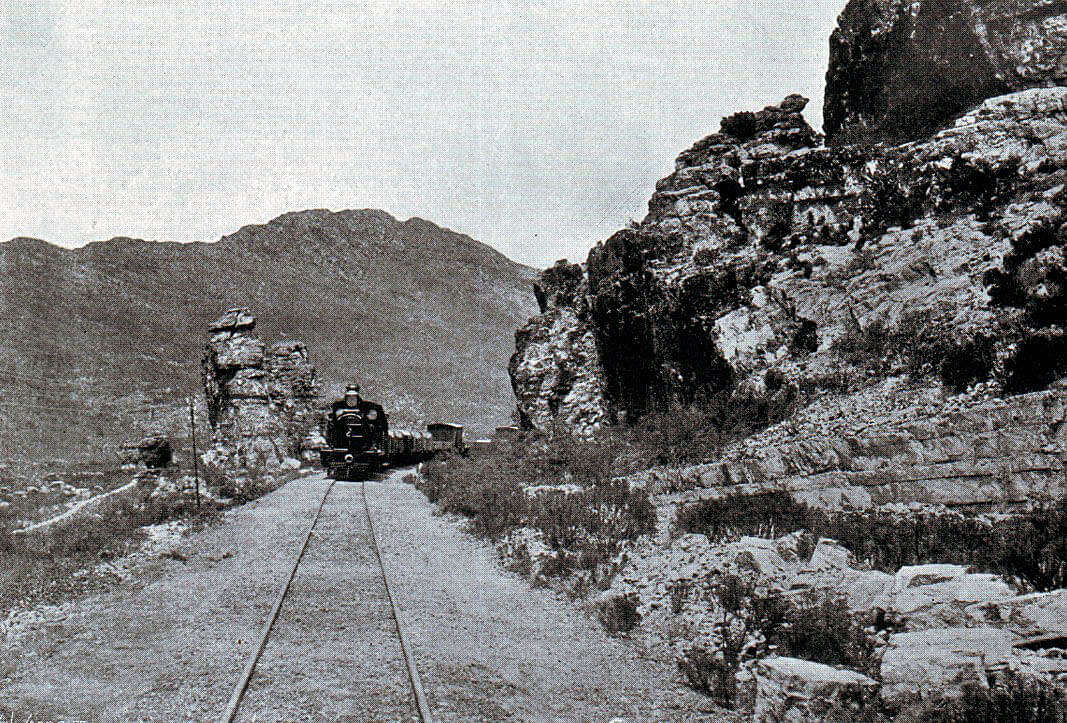

By the time Gatacre reached Queenstown the Boer invasion of Central Cape Colony had reached the railway junction of Stormberg and the town of Dordrecht to the east. Churchill described the area: ‘Stormberg Junction stands at the southern end of a wide expanse of rolling grass country, and though the numerous rocky hills, or kopjes as they are called, which rise inconveniently on all sides, make its defence by a small force difficult, a large force occupying an extended position would be secure.’

Churchill arrived at Stormberg on his way from De Aar to East London in November 1899. He found the half battalion of 1st Royal Berks and sailors from the Royal Navy about to leave the town after erecting extensive fortifications.

The abandonment of Stormberg by the British was probably unnecessary. The Boers’ inability to take any of the three towns they besieged during the war, Ladysmith, Kimberley and Mafeking, suggests that even if they had attacked Stormberg it is unlikely they would have taken it. Stormberg was a key position being the eastern junction of the main west-east railway line joining the two south-north lines in Cape Colony.

Map of the Eastern Cape and the area of operations leading to the Battle of Stormberg on 9th/10th December 1899 in the Boer War

Gatacre’s instructions from Buller were vague. He was made responsible for the East London to Aliwal North Railway line and the adjoining country up to the Orange River. Already the Boers held one hundred miles of the line south from the Orange River. Gatacre was to hold Queenstown, if possible, and East London at any rate. Gatacre described his one regiment, 1st Royal Irish Rifles, as having seen no active service since its formation in 1881.

Gatacre’s instructions required him to raise Volunteer corps from those parts of the population that were actively loyal to the British Crown.

During November 1899 Gatacre received telegraphic instructions from Buller in Natal or from General Forestier-Walker, the commander in Cape Town. These various instructions were hard to reconcile. Buller on the one hand instructed Gatacre to take no risks and wait for the substantial re-enforcements that were on their way from Britain, Canada, Australia and New Zealand and on the other hand suggested that with even the small force available to him Gatacre should be able to defeat the Boer force holding Stormberg.

On the ground Gatacre found that the loyal British population was fearful of the Boer incursion and vociferously looked to the British force to take positive steps to defend them, while the strong pro-Boer elements in the community appeared to be on the verge of joining the invaders unless deterred by vigorous action to expel the Boers. Everything in Gatacre’s character urged him to take aggressive steps against the Boers at Stormberg.

Boer burghers in the field during the South African War: Battle of Stormberg on 9th/10th December 1899 in the Boer War

On 21st November 1899 Gatacre received a telegram from Buller saying: ” I calculate it will be at least five days and probably a week before I have a second battalion to send you, or a battery of field artillery, but I am anxious to get into a position to protect the Indwe mines better than we do [Indwe with its important coal mines lay beyond Dordrecht some fifty miles along the railway spur running east from Sterkstroom]. Do you think it would be safe for you to advance your force or part of it to Stormberg, and hold that instead of Queenstown? I am told it is a good position for a force the size of yours. Of course you will have no support.”

For Gatacre this will have been little short of an order to re-take Stormberg once he received any reinforcement. For the moment he had no transport or medical services or even horses for his mounted infantry. For any movement Gatacre’s troops would have to march, carrying their stores and ammunition, or use the railway line. In the meantime Gatacre continued to reconnoitre the countryside in preparation for his attack.

On 29th November 1899 2nd Northumberland Fusiliers arrived under Gatacre’s command [2nd Northumberland Fusiliers appeared to be a unit of little if any military experience. Only the colonel in the 1888 photograph of the battalion officers wears any campaign ribbons. The regiment’s 1st Battalion had served in India until the late 1880s]. Parties of Boers were raiding the countryside and there was intense pressure from the loyal sections of the population on Gatacre to act.

As soon as the Northumberland Fusiliers arrived, Gatacre moved his force twenty-five miles up the railway line from Queenstown to Putters Kraal, with outposts further up the line at Sterkstroom and in the countryside at Bushman’s Hoek and Stenhoek.

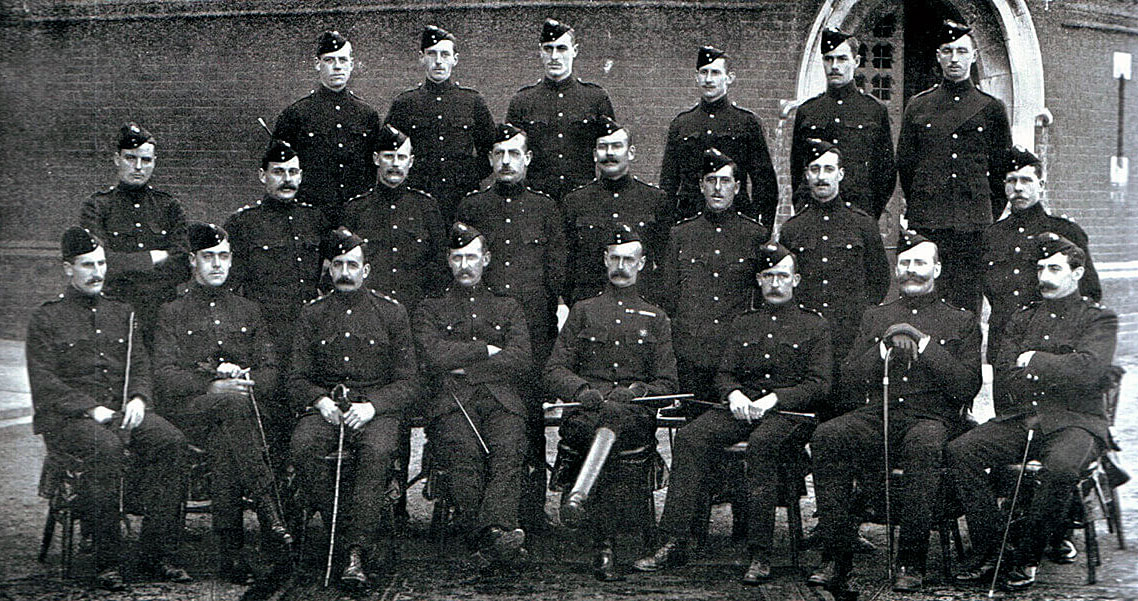

Officers of 2nd Royal Irish Rifles, one of General Gatacre’s two infantry battalions at the Battle of Stormberg on 9th/10th December 1899 in the Boer War

The distances were: Queenstown to Putter’s Kraal-25 miles, Putter’s Kraal to Sterkstroom-3 miles, Sterkstroom to Molteno-16 miles and Molteno to Stormberg-10 miles. At Sterkstroom a branch railway line headed east to Dordrecht and on to Indwe.

Gatacre received information that the Boers were destroying the railway line from Stormberg west towards the main Port Elizabeth to Colesberg line, the other south-north line running up through Cape Colony, held by General French with such units of his Cavalry Division as were not in Natal.

On 29th November 1899 Gatacre took several trains up to Molteno and brought out 7,000 bags of grain left in store by the retreating British earlier in the month.

On 2nd December Gatacre reported to Buller that the Boers were advancing south and had occupied Dordrecht in addition to Stormberg. Gatacre described his forces as occupying the Bushman’s Hoek range to prevent a Boer advance into Queenstown, which Gatacre feared would precipitate a general rebellion of the non-British population.

Buller telegraphed back: “….You have a force which altogether is considerably stronger than the enemy can now bring against you. Cannot you close with him, or else occupy a defensible position which will obstruct his advance? You have an absolutely free hand to do what you think best.”

The next day Gatacre received a telegram from General Forestier-Walker the overall commander in Cape Colony saying: ” General Buller inquires whether you can safely leave your present position and advance to Henning’s Station, or somewhere near where you can get a safe position, and also institute a policy of worry. He thinks if you could occupy Henning’s Station Boers would fall back on Burghersdorp, or if you could get near enough to Burghersdorp to make night attack, it would be the thing to stop anxiety. He adds Hildyard with a battalion and half sent a column of seven thousand Boers under Joubert himself flying. The above was probably wired before Buller read notification of the enemy’s occupation of Dordrecht. He wired last night as follows: tell Gatacre he will have to take care of himself till 5th Division arrives. A telegram just received says he has given you a free hand.”

These instructions/suggestions were unrealistic. Burghersdorp was a hundred miles up the railway north of Stormberg, the present high-water mark of the Boer advance, and Henning ten miles along the westward line out of Stormberg, a place Gatacre could only reach by train passing through Stormberg or by a flank march across mountainous country.

Non-commissioned officers of 2nd Northumberland Fusiliers, one of General Gatacre’s two infantry battalions at the Battle of Stormberg on 9th/10th December 1899 in the Boer War

The reference to Hildyard’s action against Joubert was a clear indication that Gatacre’s seniors considered he had more than enough force to defeat the Boers he faced. On the other hand Gatacre was constantly reminded that he had a free hand. It was to be his decision when and where to attack but woe betide him if he did not do so.

Gatacre’s troops were inexperienced and newly arrived in an arid mountainous country after a long sea voyage. His lack of transport and the inhospitable terrain forced Gatacre to operate on or near the railway line and he could take no action or make any preparations for action without it being quickly brought to the attention of the invading Boers by their numerous sympathisers among the Cape Colony inhabitants, the ‘Cape Dutch’.

In the first weeks of December 1899 Gatacre received reinforcements;1st Royal Scots, 74th and 77th Field Batteries Royal Field Artillery, a company of Army Service Corps and a Field Hospital. All these units were newly arrived from Britain, out of condition and unacclimatised.

But with the additional units Gatacre decided that he must attack the Boers at Stormberg before his position became untenable in the light of the constant Boer raids and the increasing defiance of the disloyal sections of the community.

1st Royal Scots would remain in camp providing guards for the railway line. The field batteries would accompany the attacking force, although they had arrived from Britain without horses and were using tram horses commandeered in South Africa with little time to train them to artillery work.

A further handicap was that there were no maps of a sufficient scale to assist Gatacre in his operations [the only map was 12 ½ miles to the inch and considered to be inaccurate]. He therefore spent the first week of December in patrols of the area around Stormberg, preparing his own sketches of the countryside. In this activity Gatacre was forced to dodge the parties of raiding Boers, having no adequate mounted force to escort him. Gatacre also questioned local inhabitants widely to obtain information on the geography of the area. Much of this information was inexact and contradictory, particularly on distance and heights.

Railway line leading into Stormberg, scene of the Battle of Stormberg on 9th/10th December 1899 in the Boer War

Gatacre conducted an extensive enquiry to find members of his force with sufficient local knowledge to act as guides for the approach march to Stormberg. He decided on five members of the Cape Mounted Police led by Sergeant Morgan.

Gatacre’s plan was to move the attacking force up to Molteno by train. From Molteno to make a night approach march up the main road that followed the railway line and attack the Boer laager or encampment on the Stormberg Nek before dawn.

Gatacre’s force concentrated at Molteno in the afternoon of 9th December 1899. The troops came up from Putters Kraal in a series of trains along the single track. Two companies of Royal Irish Rifles joined the trains from the outlying posts at Bushman’s Hoek, a post half way to Molteno a mile to the west of the railway line. 235 of the Cape Mounted Rifles, with five mountain guns and two maxims, from the post at Penhoek some ten miles east on the line to Dordrecht, were intended to join the force at Sterkstroom, but the telegraph operator omitted to send the order summoning them and they failed to appear (query whether this was inefficiency or deliberate sabotage). It is hard to see such an omission being overlooked if Gatacre had been served by a sufficient trained staff.

Two companies of 2nd Royal Irish Rifles marching from Bushman’s Hoek to join the train before the Battle of Stormberg on 9th December 1899 in the Boer War

There could be no possibility of concealing the movement of the British force from the Boers at Stormberg, involving as it did the concentration of two and a half thousand soldiers at the various stations and the movement of several trains, with the troops in open trucks accompanied by the twelve guns of the two field batteries, over a distance of some twenty miles through country peopled by Boer sympathisers and probably with Boer patrols on the neighbouring mountains.

Gatacre is criticised because his two infantry battalions came straight from arduous training and working programs to the operation without the opportunity to rest and were held in the open sun for some hours by delays on the railway. Gatacre acknowledged that there was substance in this criticism. This criticism can be dismissed as a minor objection against the background of lack of resources and time available.

British troops on a train near Stormberg scene of the Battle of Stormberg on 9th/10th December 1899 in the Boer War

Gatacre assembled at Molteno 74th and 77th Field Batteries Royal Field Artillery, half of 33rd Company Royal Engineers, 2nd Northumberland Fusiliers, 2nd Royal Irish Rifles and a detachment of dismounted Mounted Infantry, 2,600 men in all, with 12 guns.

Officers of 2nd Northumberland Fusiliers, one of General Gatacre’s two infantry battalions at the Battle of Stormberg on 9th/10th December 1899 in the Boer War

Once at Molteno Gatacre received a report that the Boers had entrenched the pass between the Kissieberg and Rooi Kop which carried the railway and the road into Stormberg. Gatacre was assured by his informant that the Boer laager was on the Kissieberg and that this could be climbed on the western side. The guides assured Gatacre that this approach would involve an additional two miles of march and that they knew the way, which would be along the road to Steynsberg with a turning to the right that would take the column under the southern end of the Kissieberg.

In the light of this information Gatacre decided to change the operation so that instead of an attack up the Stormberg road the attack would be made on the south-western corner of the Kissieberg with an approach march up the Steynsberg road and a right hand turn onto a minor track leading into the valley to the west of the Kissieberg.

Gatacre assembled a conference of his senior officers in the station master’s office at Molteno and gave them the up to date situation. Gatacre enquired into the men’s condition and was assured by his officers that their men were ready for the operation.

Cape Mounted Rifles with maxim machine guns at Penhoek. The railway telegraph clerk failed to send the order for the unit to join Gatacre’s force for the Battle of Stormberg on 9th December 1899 in the Boer War

It had been intended that the march would begin at 7pm but there was considerable difficulty in organizing the number of trains on the single line and a two hour delay developed. Gatacre considered an overnight stop at Molteno with the attack postponed to the next evening and decided to begin the operation as planned that evening. Gatacre estimated that the approach march would take 6 hours.

The change of route was not communicated to the field ambulance and column of reserve ammunition which came up to Molteno by road. They took the original main road towards Stormberg, returning when they realised that the column was not in front of them, and being sent back up the road for a second time by the intelligence officer left in Molteno who also had not been informed of the change of plan.

The march began at 9pm with the soldiers reported as setting off at an eager and brisk pace. The night started off with a strong moon, which disappeared leaving the column in complete darkness.

At 12.30am the column reached a colliery railway line. Gatacre realised that the column had missed the turning to the right and was now marching towards Steynsberg. The column halted while Gatacre discussed the new situation with the chief guide. Sergeant Morgan reported that the column could take a turning to the right further on and would arrive under the Kissieberg with only an additional two miles added to the route. The troops rested for forty five minutes and resumed the march. The column again crossed the colliery railway which formed a wide left hand semi-circle and came into the valley beneath the Kissieberg.

The guides appear to have thought that the second crossing of the line was the main Colesberg to Stormberg line from the west. They had become thoroughly disorientated.

At 4.20am the column was under a face of the Kissieberg, but further north than Gatacre had planned. Ironically it seems that the column marched past the spot picked by Gatacre for the attack but in the dark failed to identify it and marched on.

It was now nearly sunrise (5.15am) and a Boer rifleman fired a shot from the top of the mountain alerting his comrades who took up positions along the summit.

It is generally accepted that the Boers were otherwise unprepared for the British attack.

2nd Northumberland Fusiliers begin the attack on the Kissieberg at the Battle of Stormberg on 9th/10th December 1899 in the Boer War: picture by Edward Read

Three companies of the leading 2nd Royal Irish Rifles moved on and occupied positions on a hill at the northern end of the valley. The remainder of the Royal Irish Rifles and the following 2nd Northumberland Fusiliers began to scale the Kissieberg Mountain on their left. The Boers assembled on the crest and fired down on the British troops. A Boer gun was brought up and also opened fire from the crest.

The point Gatacre had intended for the assault was believed to be accessible. Where the column in fact made the attack the Kissieberg was steep and in parts comprised sheer rock faces that could not easily be climbed by the troops.

The 77th Field Battery came into action near the hill face while the 74th Field Battery moved to the left and came into action in the valley. The mounted infantry remained with the guns as escort.

The British guns burst shrapnel on the crest of the hill to some effect silencing the Boer gun for a time.

The infantry advance up the side of the Kissieberg continued for half an hour making progress albeit slowly due to the difficult terrain. The Boer fire appeared to be slackening.

A number of events took place during the operation which are difficult to put into the chronology with precision. A Boer raiding party said to number around five hundred, attracted by the firing, appeared on the hill top on the western side of the valley, opposite the Kissieberg, and opened fire on the British. The 74th Field Battery turned and opened fire on these Boers, firing ‘trail to trail’ with 77th Field Battery, which was firing in the other direction onto the Kissieberg.

It seems clear that the infantry climbing the Kissieberg in several places found they could make no further progress up the mountain due to the sheer stone ridges. The commanding officer of 2nd Northumberland Fusiliers gave orders that his battalion withdraw off the hillside. Five companies of the Fusiliers received this order and began to climb down, but three of the battalion’s companies, of which Captain Wilmott was the senior officer, remained with the Royal Irish Rifles further up the mountain.

The gun batteries seeing the Fusiliers coming down into the valley assumed that there was a general retreat and that it was necessary to bring their fire down from the mountain crest. The directing gunner officers were considerably hampered by the dawn sun breaking over the top of the mountain, shining into their eyes and throwing the mountain side into darkness. The British artillery rounds began to fall among the Royal Irish Rifles and Fusiliers still near the top of the mountain.

Lieutenant Colonel Eager, the commanding officer of 2nd Royal Irish Rifles, discussed the situation with Captain Wilmott who urged that the troops were nearly at the crest and that the attack should continue. Eager assembled his senior officers near the top of the mountainside to confer over what action to take when a British shrapnel shell burst over this conference wounding all the officers, Lieutenant-Colonel Eager, Major H. J. Seton, the second-in-command, Major Welman and Captain Bell. Colonel Eager subsequently died of his injuries.

Gatacre’s troops return to Molteno after the Battle of Stormberg on 9th/10th December 1899 in the Boer War: picture by H.C. Seppings Wright

It would seem that at some points on the mountain there was very little preventing the British infantry from reaching the top of the Kissieberg and taking the Boer positions. A Boer official reported later that Boers were already leaving their positions due to the threat of being overrun. A Royal Irish Rifles officer was convinced that Colonel Eager, his two majors and the senior captain were about to make the decision to continue the attack when they all became casualties from the British shell burst.

It may be that Colonel Eager took the view that with the loss of the five companies of Northumberland Fusiliers and the fire of the British guns on their own men the attack could not succeed and that the troops must withdraw.

Whatever the source of the order, if one was in fact given, many of the British troops on the Kissieberg climbed back down.

Others of the British troops, unaware of the withdrawal, stayed put on the mountainside moving neither up nor down, exchanging fire with the increasingly re-enforced Boer line.

As the main body of troops came down into the valley, both Northumberland Fusiliers and Royal Irish Rifles, it was clear to Gatacre that they were in no fit state to renew the attack and that a return to Molteno was necessary.

The withdrawal was further hampered by the Boers firing from the western heights adding to the confusion of the retreat.

Gatacre’s ADC describes Gatacre as working hard to ensure that the men came off the mountain and spent the return march bringing in exhausted soldiers who had fallen by the wayside and supervising the recovery of abandoned transport. The Boers made no serious effort to impede Gatacre’s retreat.

Wounded Lieutenant Stephens of 2nd Royal Irish Rifles carried by four privates back to Molteno after the Battle of Stormberg on 10th December 1899 in the Boer War: picture by F.J. Waugh

The British troops began to march in to Molteno at 11am and the whole force was back by 12.30pm. The inhabitants of Molteno turned out to assist the returning exhausted soldiers, providing them with water and food.

Rolls were called and it was then realised that many troops could not have received the order to withdraw and been left on the mountainside in the confusion of the descent or collapsed in exhaustion on the route back. Of the force of 2,600 men, 13 officers and 548 men were missing, all Boer prisoners.

Casualties at the Battle of Stormberg:

British casualties were given officially as 8 officers wounded of whom 1 died (Lieutenant Colonel Eager) and 13 missing, all captured, and 25 soldiers killed, 102 wounded and 548 missing, some killed but the majority captured.

1 gun was lost, stuck in boggy ground.

Boer casualties were trivial and are unknown.

Follow-up to the Battle of Stormberg:

The consequences of Gatacre’s failure were in no way adverse on the ground. Gatacre moved his base further north on the railway to Sterkstrom and the Boers made no move, other than to withdraw from Dordrecht, which Gatacre re-occupied. The numbers of Cape Dutch joining the Boer ranks did not increase particularly.

British troops recovering collapsed comrades on the road to Molteno after the Battle of Stormberg on 9th/10th December 1899 in the Boer War: picture by Edward Read

In terms of public relations the consequences were volcanic. Stormberg, Magersfontein and Colenso were the British defeats that made up “Black Week”, a term coined by Fleet Street. Gatacre’s reputation was irretrievably damaged. Lord Lansdowne, the Secretary of State for War, directed Buller to dismiss Gatacre along with Methuen, held responsible for the defeat at Magersfontein. Buller did not do so and Gatacre remained in command of the 3rd Division, a line of communication formation, for the time being.

Gatacre was relieved of his command on 10th April 1900, following the capture of two companies of 2nd Royal Irish Rifles at DeWetsdorp, and ordered to return to England. This was the effective end of his military career. Gatacre left the Army in 1904 and died of fever in the Sudan in 1906.

Although there were more failures for the British, Lord Roberts in the West and General Buller in Natal pushed the Boers back, relieving Kimberley, Mafeking and Ladysmith, capturing the capitals of the Free State, Bloemfontein, and the Transvaal, Pretoria, and finally after a protracted guerilla campaign bringing the war to a successful conclusion for the British on 31st May 1902.

The Operation at the Battle of Stormberg:

Almost every account of the Boer War seems to search for criticisms to level against Gatacre in what has been a campaign of ridicule and denigration sustained over the century since the battle.

Gatacre described the operation as “a most lamentable failure, and yet within an ace of being the success I anticipated……The fault was mine, as I was responsible of course. I went rather against my better judgment in not resting the night at Molteno, but I was tempted by the shortness of the distance and the certainty of success. It was so near being a brilliant success.”

Populace of Molteno provide water and food to the returning British troops after the Battle of Stormberg on 9th/10th December 1899 in the Boer War: picture by Albert Morrow

The Official History of the South African War stated: “Sir William Gatacre’s decision to advance on Stormberg was fully justified by the strategical situation. General Buller’s telegram, although it left him a free hand as to time and opportunity, had suggested that operation. The plan, though bold, was sound in its design, and would have succeeded had not exceptional misfortune attended its execution.”

The main criticisms levelled against Gatacre seem to be that he was wrong to conduct a night march at all, that he failed to conduct the operation with sufficient secrecy (a widely made allegation that ignores the reality that every British action was reported to the Boers by the ‘Cape Dutch’ and that in spite of the lack of secrecy the Boers were surprised by the attack), that he failed to conduct sufficient reconnaissance, that there were officers and soldiers familiar with the terrain that he failed to take on the expedition, that he failed to turn back once it was clear that the wrong route had been taken and that finally he failed to take sufficient steps to get all his men off the mountain and bring them back.

The reality is that once a military operation has gone wrong any criticism seems valid. It only required a group of Gatacre’s men to find a way to the top, which could easily have happened, and it was very likely that the attack would have been a resounding success with the Boers driven off in flight and Stormberg captured. No criticism of any sort would then have been levelled.

At least one of the junior officers on the mountain considered that if Colonel Eager had ordered the attack to continue the troops were so near the top in places that they would have succeeded, particularly as the Boers were already melting away.

Essentially Gatacre’s difficulty was that he was required to undertake an operation with a small number of inexperienced, inadequately trained troops, insufficient equipment, a lack of trained staff officers, no maps, on ground neither he nor anyone else available to him seemed to be sufficiently familiar with. In such circumstances the odds were heavily stacked against Gatacre.

General Gatacre in India in the 1880s: Battle of Stormberg on 9th/10th December 1899 in the Boer War

Lord Roberts in a memorandum to the Secretary of State for War dated 16th April 1900 wrote of the Stormberg battle: “In my opinion, Lieut.-General Gatacre on this occasion showed a want of care, judgment, and even of ordinary military precautions…..”

Probably the most telling criticism of Gatacre is that he prepared the operation on the basis of an approach march along the main Molteno-Stormberg road that followed the railway line and at short notice changed the operation to one based on a new and less certain route along the Steynsberg road. Even if Sergeant Morgan knew the area well it is hard to criticize him for missing the turning off the new route on a moonless night. Here can be seen the impetuous streak that dominated Gatacre’s character, usually to his advantage, but at Stormberg to his destruction.

The change of route was so precipitate and ill-organised that an important part of the force, the following field ambulance and ammunition column were not informed and used the Stormberg road.

Gatacre acknowledged after the battle that he should have waited to the next day before launching the attack.

Battle Honours:

Stormberg is not a battle honour. All the regiments that fought in South Africa received the battle honour ‘South Africa’ with the dates of presence in the country.

Regimental anecdotes and traditions relating to the Battle of Stormberg:

- General Gatacre was known to the troops as “back acher” because of the burdens he imposed on them and on himself. Once disgraced, this nickname, born of wry admiration and affection on the part of Gatacre’s men, became a term of public derision.

- One of the many stories arising from Stormberg is that Gatacre is reputed to have shot the guide who led the column. This is untrue. The guide, Sergeant Morgan, gave evidence to the subsequent Board of Enquiry, saying that he became confused over the route.

- Gatacre’s widow Lady Beatrix Gatacre wrote a biography of her husband published in 1910 designed to rehabilitate his memory entitled General Gatacre: The story of the life and services of Sir William Forbes Gatacre, K.C.B., D.S.O. 1843-1906.

- The provision of tram horses to the two field batteries on their arrival in South Africa gave rise to a story involving a gunner unable to make his new horse move. His comrade called out “don’t bother with yer spurs, Fred. Ring yer bleedin’ bell.”

Queen’s South Africa Medal with clasps for ‘Natal’ ‘Belmont’ and ‘Modder River’: Battle of Stormberg on 9th/10th December 1899 in the Boer War

References for the Battle of Stormberg:

The Boer War is widely covered. A cross section of interesting volumes would be:

The Times History of the War in South Africa

The Great Boer War by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle

Goodbye Dolly Gray by Rayne Kruger

With the Flag to Pretoria by HW Wilson

General Gatacre: The story of the life and services of Sir William Forbes Gatacre, K.C.B., D.S.O. 1843-1906 by Lady Beatrix Gatacre (widow)

The Boer War by Thomas Pakenham (Stormberg is only mentioned in passing)

South Africa and the Transvaal War by Louis Creswicke (6 highly partisan volumes)

63. Podcast on the Battle of Stormberg: General Gatacre’s disastrous defeat in Northern Cape Colony, fought on 9th/10th December 1899 in the Boer War; the first battle of ‘Black Week’: John Mackenzie’s britishbattles.com podcasts

63. Podcast on the Battle of Stormberg: General Gatacre’s disastrous defeat in Northern Cape Colony, fought on 9th/10th December 1899 in the Boer War; the first battle of ‘Black Week’: John Mackenzie’s britishbattles.com podcasts

The previous battle in the Boer War is the Battle of Modder River

The next battle in the Boer War is the Battle of Magersfontein

© britishbattles.com.