The final battle fought by Buller’s Natal Field Force between 14th and 28th February 1900, leading to the relief of Ladysmith and the Boer retreat from Natal

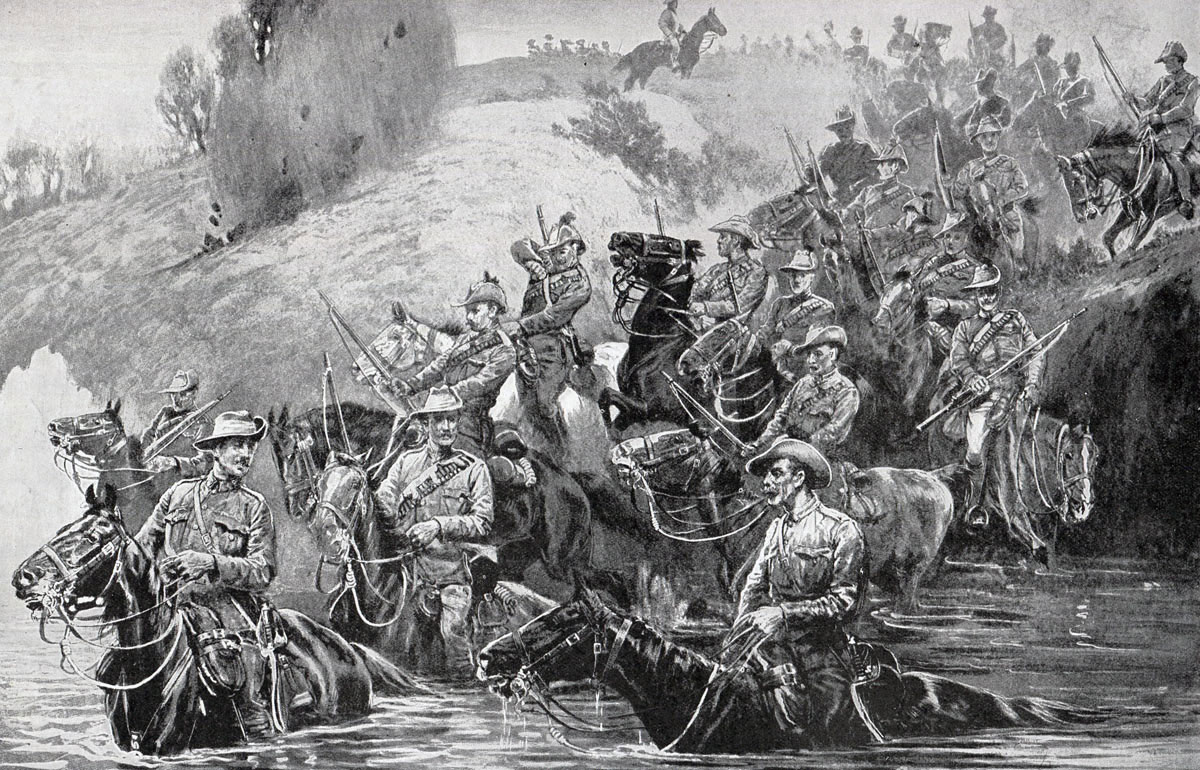

Lord Dundonald’s cavalry pursuing the Boers at the end of the Battle of Pieters fought from 14th to 28th February 1900 in the Great Boer War: picture by Richard Caton Woodville

67. Podcast on the Battles of Val Krantz and Pieters fought between 5th and 28th February 1900 in the Boer War: The third unsuccessful attempt by Buller to push across the Tugela River followed by the fourth, final and successful crossing of the Tugela, leading to the relief of Ladysmith: John Mackenzie’s britishbattles.com podcasts

67. Podcast on the Battles of Val Krantz and Pieters fought between 5th and 28th February 1900 in the Boer War: The third unsuccessful attempt by Buller to push across the Tugela River followed by the fourth, final and successful crossing of the Tugela, leading to the relief of Ladysmith: John Mackenzie’s britishbattles.com podcasts

The previous battle of the Great Boer War is the Battle of Val Krantz

The next battle of the Great Boer War is the Battle of Paardeberg

Colonials crossing a spruit under fire: Battle of Pieters, fought from 14th to 28th February 1900 in the Great Boer War: picture by John Charlton

War: The Great Boer War

Date of the Battle of Pieters: 14thFebruary to 28th February 1900.

Place of the Battle of Pieters: The Tugela River, Northern Natal in South Africa.

Combatants at the Battle of Pieters: British against the Boers.

Commanders at the Battle of Pieters: Lieutenant General Sir Redvers Buller against General Botha.

Size of the armies at the Battle of Pieters: 20,000 British and colonial troops against between 4,000 to 8,000 Boers, as they returned to their commandos.

Uniforms, arms and equipment at the Battle of Pieters: The Boer War was a serious jolt for the British Army. At the outbreak of the war, British tactics were appropriate for the use of single shot firearms, fired in volleys controlled by company and battalion officers, the troops fighting in close order. The need for tight formations had been emphasised time and again in colonial fighting. In the Zulu and Sudan Wars, overwhelming enemy numbers, armed principally with stabbing weapons, were easily kept at a distance by such tactics; but, as at Isandlwana, would overrun a loosely formed force. These tactics had to be entirely rethought in battle against the Boers armed with modern weapons.

Lord Dundonald’s cavalry pursuing the Boers at the end of the Battle of Pieters from 14th to 28th February 1900 in the Great Boer War: picture by Lucy Kemp-Welch

In the months before hostilities, the Boer commandant general, General Joubert, bought 30,000 Mauser magazine rifles and a number of modern field guns and automatic weapons from the German armaments manufacturer Krupp and the French firm Creusot. The Boer commandoes, without formal discipline, welded into a fighting force through a strong sense of community and dislike for the British. Field cornets led Boer burghers by personal influence, not through any military code. The Boers did not adopt military formation in battle, instinctively fighting from whatever cover there might be. Many Boers were countrymen, running their farms from the back of a pony with a rifle in one hand. These rural Boers brought a life time of marksmanship to the war, an important edge, further exploited by Joubert’s consignment of German magazine rifles. Viljoen is said to have coined the aphorism ‘Through God and the Mauser’ to describe the national inspiration. With strong fieldcraft skills and high mobility, the Boers were natural mounted infantry. The urban burghers and foreign volunteers readily adopted the fighting methods of their rural comrades.

Other than in the regular uniformed Staats Artillery and police units, the Boers wore their everyday civilian clothing on campaign.

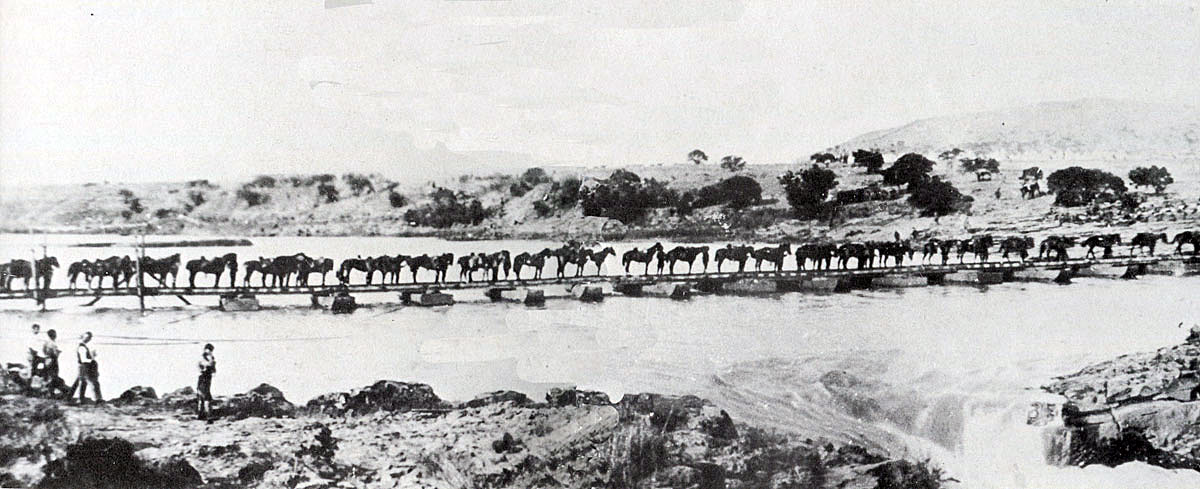

British cavalry crossing the Tugela River on 27th February 1900 during the Battle of Pieters in the Great Boer War

After the first month of the war, the Boers lost their numerical superiority, spending the rest of the formal war on the defensive against British forces, that regularly outnumbered them.

British tactics, used at Modder River, Magersfontein, Colenso and Spion Kop, were incapable of winning battles against entrenched troops armed with modern magazine rifles. Every British commander made the same mistake; Buller; Methuen, Roberts and Kitchener. When General Kelly-Kenny attempted to winkle Cronje’s commandoes out of their riverside entrenchments at Paardeberg using his artillery, Kitchener intervened and insisted on a battle of infantry assaults; with the same disastrous consequences as in earlier battles.

South African Light Horse: Battle of Pieters, fought from 14th to 28th February 1900 in the Great Boer War

Some of the most successful British troops were the non-regular regiments; the City Imperial Volunteers, the South Africans, Canadians, Australians and New Zealanders, who more easily broke from the habit of traditional European warfare, using their horses for transport rather than the charge, advancing by fire and manoeuvre in loose formations and making use of cover, rather than the formal attack in line into a storm of Mauser bullets.

Uniforms, equipment and training: The British regiments made an uncertain change into khaki uniforms in the years preceding the Great Boer War, with the topee helmet as tropical headgear. Highland regiments in Natal devised aprons to conceal coloured kilts and sporrans. By the end of the war, the uniform of choice was slouch hat, drab tunic and trousers. The danger of shiny buttons and too ostentatious emblems of rank was emphasised in several engagements with disproportionately high officer casualties. From early in the war many British officers stopped wearing their swords and carried rifles, to make themselves less conspicuous to Boer marksmen.

The British infantry were armed with the Lee-Metford magazine rifle, firing 10 rounds. But no training regime had been established to take advantage of the accuracy and speed of fire of the weapon. Personal skills such as scouting and field craft were little taught. The idea of fire and movement was unknown, many regiments still going into action in close order.

Notoriously, General Hart insisted that his Irish Brigade fight shoulder to shoulder, as if on parade in Aldershot. Short of regular troops, Britain engaged volunteer forces from Britain, Canada, Australia and New Zealand, who brought new ideas and more practical formations to the battlefield.

Picket of the 15th Hussars near Hussar Hill during the Battle of Pieters, fought from 14th to 28th February 1900 in the Great Boer War: picture by John Charlton

The British regular troops lacked imagination and resource. Routine procedures such as effective scouting and camp protection were often neglected. The war was littered with incidents in which British contingents became lost or were ambushed, often unnecessarily, and forced to surrender. The war was followed by a complete re-organisation of the British Army.

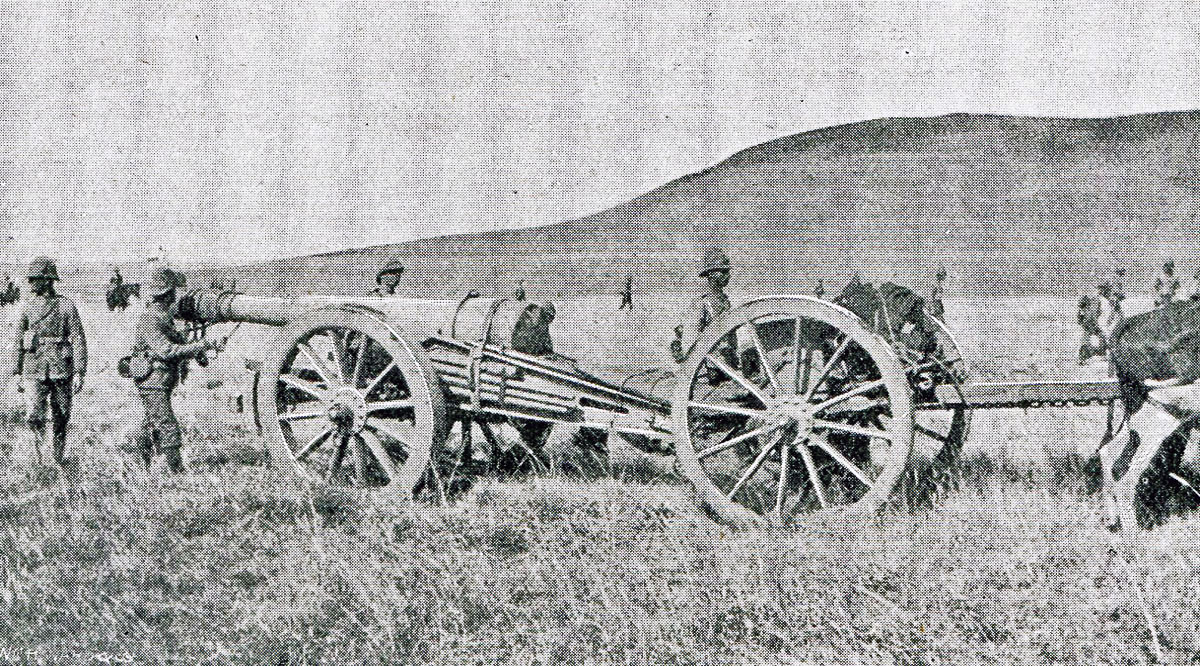

The British artillery was a powerful force in the field, underused by commanders with little training in the use of modern guns in battle. Pakenham cites Pieters as being the battle at which a British commander, surprisingly Buller, developed a modern form of battlefield tactics: heavy artillery bombardments, co-ordinated to permit the infantry to advance under their protection. It was the only occasion that Buller showed any real general ship and the short inspiration quickly died.

British Army 5 inch howitzer: Battle of Pieters, fought from 14th to 28th February 1900 in the Great Boer War

The Royal Field Artillery fought with 15 pounder guns; the Royal Horse Artillery with 12 pounders and the Royal Garrison Artillery batteries with 5-inch howitzers. The Royal Navy provided heavy field artillery with a number of 4.7-inch naval guns, mounted on field carriages devised by Captain Percy Scott of HMS Terrible.

Automatic weapons were used by the British, usually mounted on special carriages accompanying the cavalry.

Winner of the Battle of Pieters: Finally, the British.

British Order of Battles at the Battle of Val Krantz and Pieters:

South African Imperial Light Horse: Battle of Pieters 14th to 28th February 1900 in the Great Boer War

Cavalry (Earl of Dundonald)

1st Royal Dragoons

13th Hussars

Bethune’s Mounted Infantry

Thorneycroft’s Mounted Infantry

Natal Carabineers

South African Light Horse

Imperial Light Horse

Imperial Light Infantry

Natal Police

Second Division under Lieutenant General Sir C. F. Clery

Second Brigade (commanded by Major General Hildyard)

2nd East Surreys

2nd West Yorks

2nd Devons

2nd Queen’s West Surreys

Fourth Brigade (commanded by Major General Lyttelton)

1st Rifle Brigade

1st Durham Light Infantry

3rd King’s Royal Rifle Corps

2nd Scottish Rifles (the old 90th Light Infantry)

Squadron of the 14th Hussars

7th, 14th and 66th Batteries, Royal Field Artillery (less the ten guns lost at the Battle of Colenso)

Third Division:

Fifth Irish Brigade (commanded by Major General Hart)

1st Inniskilling Fusiliers

1st Connaught Rangers

1st Royal Dublin Fusiliers

1st Border Regiment

Sixth Fusilier Brigade (commanded by Major General Barton)

2nd Royal Fusiliers

2nd Royal Scots Fusiliers

1st Royal Welch Fusiliers

2nd Royal Irish Fusiliers

Squadron 14th Hussars

63rd, 64th and 73rd Batteries Royal Field Artillery.

Fifth Division (Lieutenant General Sir Charles Warren)

Tenth Brigade (commanded by Major General Coke)

2nd Dorset Regiment

2nd Middlesex Regiment

Eleventh Brigade (commanded by Colonel Walter Kitchener)

2nd King’s Royal Lancaster Regiment

2nd Lancashire Fusiliers

1st South Lancashire Regiment

1st York and Lancaster Regiment

19th, 20th and 28th Batteries Royal Field Artillery.

Corps troops:

2nd Royal Dublin Fusiliers

2nd Somerset Light Infantry

61st Battery (Howitzers)

Natal Battery with 9 pounders

Battery of six Royal Navy 12 pounders

4th Mountain Battery

4.7 Inch Royal Navy guns

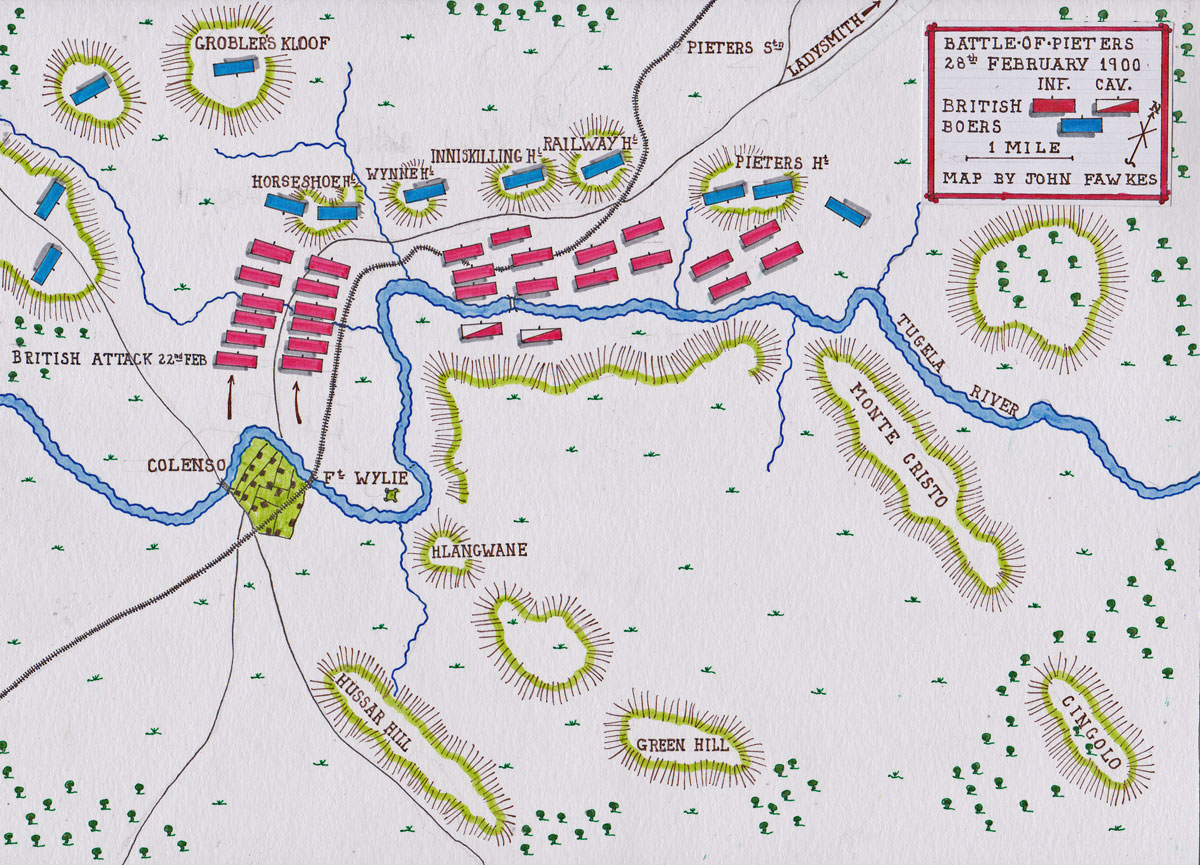

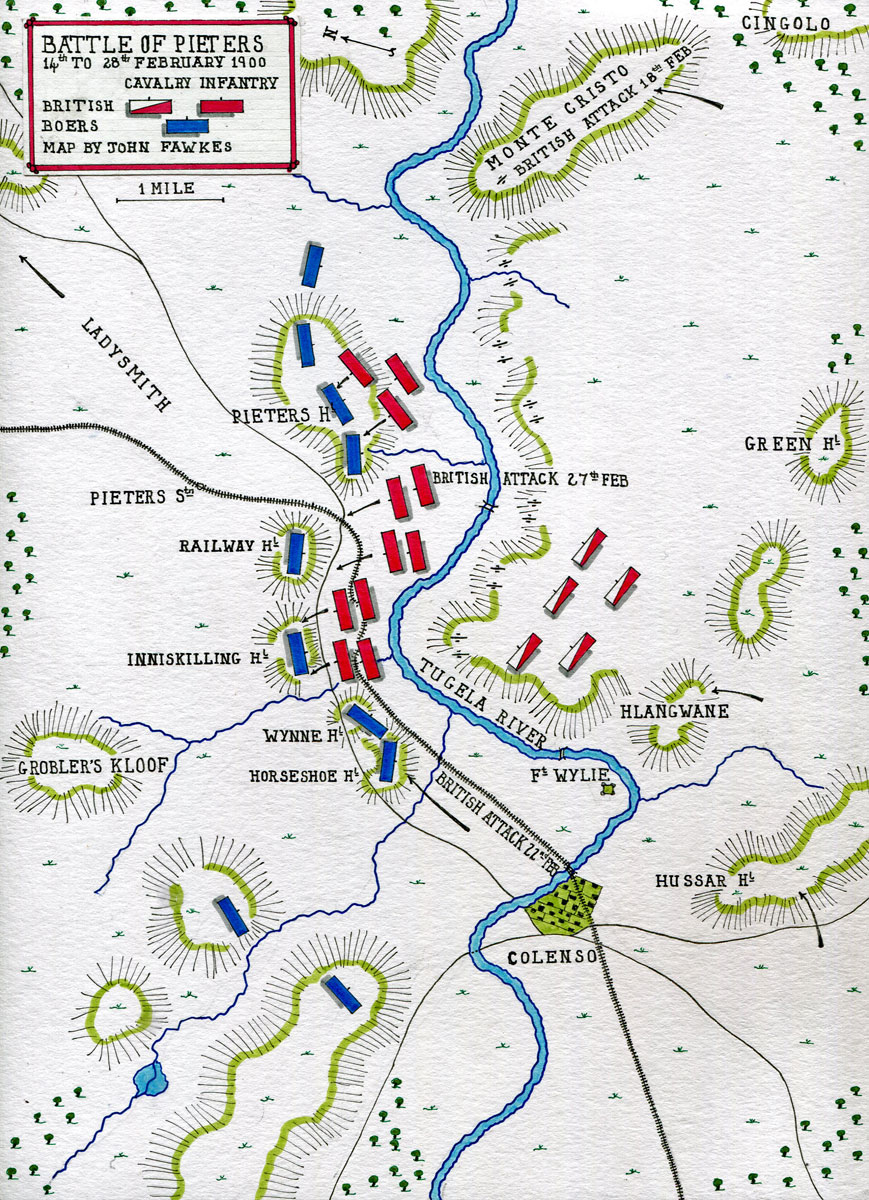

Map of the Battle of Pieters fought from 14th to 28th February 1900 in the Great Boer War: map by John Fawkes

Account of the Battle of Pieters:

Buller’s fourth and final attack across the Tugela began on 12th February 1900, further east at Colenso. A force of Byng’s South African Light Horse assaulted Hussar Hill, which they took. Buller arrived and ordered the hill to be abandoned, the whole force retiring to the British base at Chievely.

West Yorkshire Regiment on Monte Cristo: Battle of Pieters, fought from 14th to 28th February 1900 in the Great Boer War

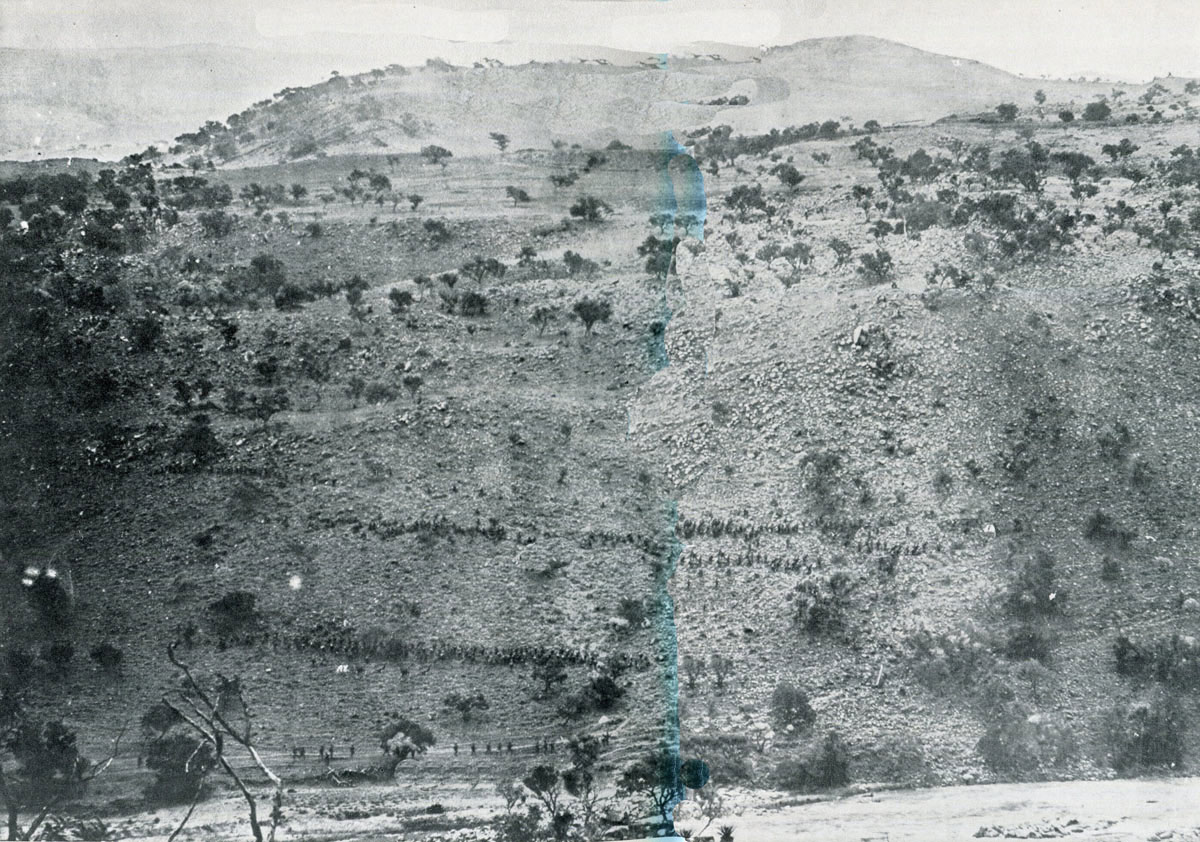

On 14th February 1900, Buller resumed the attack, taking Hussar Hill again. From there the offensive assumed an unstoppable momentum. British troops moved from hill to hill, pushing back the despondent Boers, whose morale was sinking at the news of defeat in the west.

Queen’s West Surrey Regiment on Monte Cristo: Battle of Pieters, fought from 14th to 28th February 1900 in the Great Boer War: picture by Oscar Eckhardt

The British took the hills of Cingolo, Monte Cristo and finally Hlangwane, forcing the Boers back across the Tugela River. Buller, ever-cautious, failed to launch his troops in pursuit of the retreating Boers.

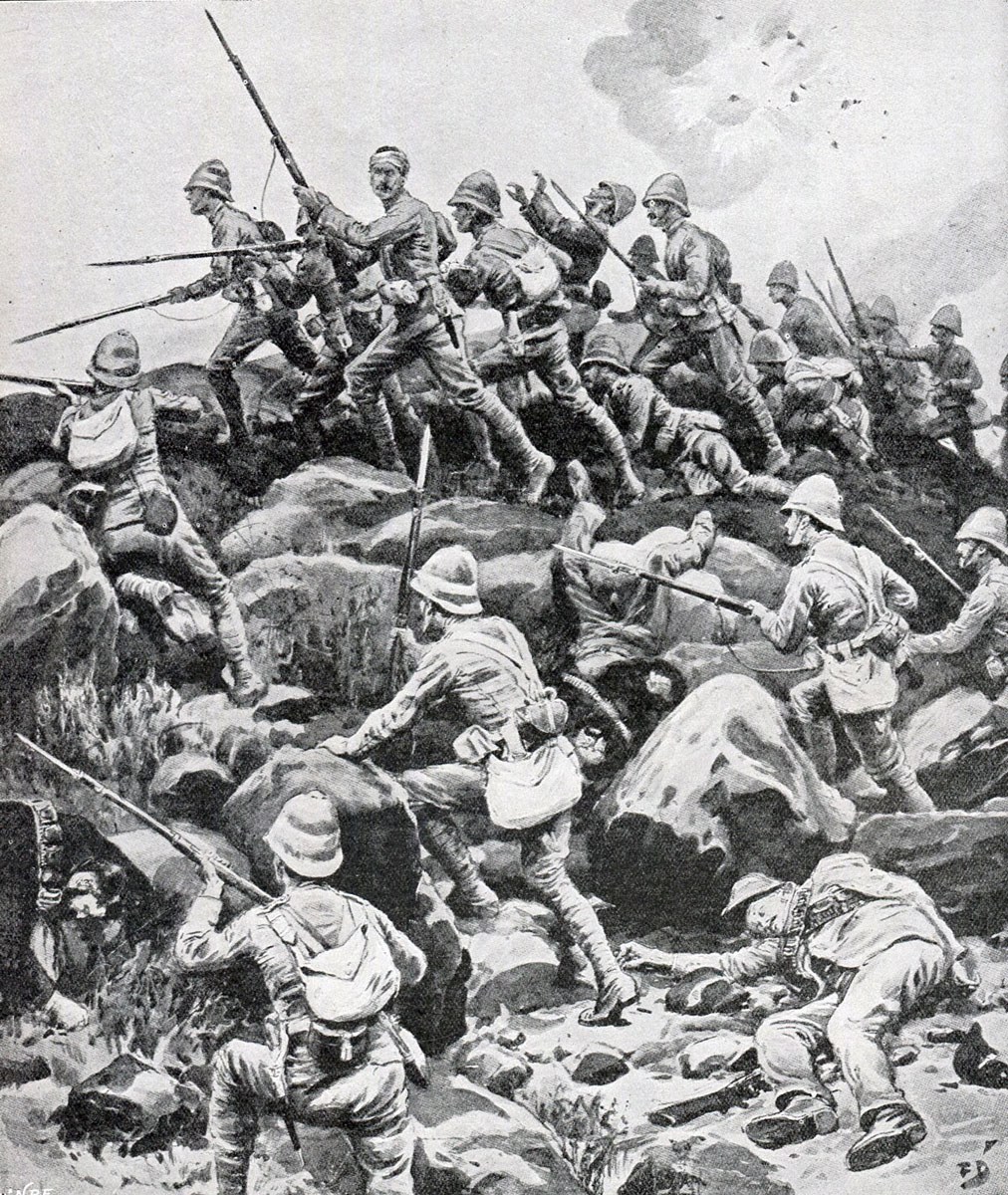

Last rush at Hlangwane Hill: Battle of Pieters, fought from 14th to 28th February 1900 in the Great Boer War

The next stage involved the inevitable attack across the Tugela River. Buller decided to launch the assault west of Colenso, although this was on ground covered by the disastrous Colenso battle.

In the lull, as Buller decided on the next move and the pontoon bridge was laid across the Tugela, the eccentric General Warren had his bath assembled and stripped naked to take a wash. He did it, he claimed, to amuse the troops. Buller arrived during the proceedings.

Charge of the Inniskillings at the Battle of Pieters, fought from 14th to 28th February 1900 in the Great Boer War: picture by Lance Thackeray

The British artillery moving up to the river, a heavy bombardment was opened on the Boer positions in the hills to the north of the Tugela. Buller’s infantry crossed the river and began an assault on the string of hills along the bank of the river from west to east, called Horseshoe, Wynne’s and Inniskilling Hills. Casualties were high and there was little success.

King’s Royal Lancaster Regiment storming Pieters Hill: Battle of Pieters, fought from 14th to 28th February 1900 in the Great Boer War: picture by Frank Dadd

On 27th February 1900, the pontoon bridge was moved to a position further east along the river and the British launched an attack across the Tugela on the hills leading to Ladysmith. In the final fighting of the battle, Barton’s Brigade captured Pieter’s Hill: Norcott’s Fourth Brigade (Norcott had taken over from Lyttelton, who now commanded the Division) moved to relieve Hart on Inniskilling Hill and Kitchener’s Eleventh Brigade took Railway Hill. The Boer positions crumbled and they retreated in some confusion towards the Natal border, joined by the Boers from the siege lines around Ladysmith. Ladysmith was relieved the next day and the Boer invasion of Natal brought to a close.

British Sixth Brigade climbing Pieters Hill: Battle of Pieters, fought from 14th to 28th February 1900 in the Great Boer War

Casualties at the Battle of Pieters: The extended period of fighting in February 1900 cost Buller’s Natal Field Force around 3,000 casualties, 500 of them suffered by Hart’s brigade during the attack on Inniskilling Hill. The Boers probably suffered around 1,500 casualties.

West Yorks watching the Boers retreat from the top of Pieters Hill: Battle of Pieters, fought from 14th to 28th February 1900 in the Great Boer War: picture by H.C. Seppings Wright

Follow-up to the Battle of Pieters:

The attack across the Tugela by Barton’s, Norcott’s and Kitchener’s brigades is described as the one occasion when Buller behaved as a general; committing his forces in strength in a co-ordinated attack. This period of inspiration was soon over, leaving the old Buller, timid and a pray to self-doubt. As the Boer army broke up in retreat, Dundonald and other generals urged Buller to unleash his cavalry in pursuit. That it was a golden opportunity is confirmed by Denys Reitz in his book ‘Commando’. Buller, unwilling to assume any risk, refused. White attempted to launch his cavalry and horse artillery after the retreating Boers, but the troops and horses broke down within a few miles from malnourishment.

General Buller’s Natal Field Force entering Ladysmith on 28th February 1900 after the Battle of Pieters, fought from 14th to 28th February 1900 in the Great Boer War

On 28th February 1900, General Buller led his Natal Field Force into Ladysmith and the siege of the British troops in the town was over.

Battle Honours:

The Relief of Ladysmith and the Defence of Ladysmith were battle honours awarded to regiments that took part. Soldiers received the equivalent clasp for their Queen’s South Africa Medal.

Anecdotes from the Battle of Pieters:

- It an irony that in the First World War, between 1917 and 1919, Deneys Reitz, who fought as a Boer soldier in the Boer War, commanded a battalion of the Royal Scots Fusiliers, one of the regiments he fought against in Natal.

British Generals White and Buller meet in Ladysmith, after the relief of the town following the Battle of Pieters, fought from 14th to 28th February 1900 in the Great Boer War

References for the Battle of Pieters:

The Boer War is widely covered. A cross section of interesting volumes would be:

Queen’s South Africa Medal with clasp for ‘Relief of Ladysmith’ and King’s South Africa Medal: Battle of Pieters, fought from 14th to 28th February 1900 in the Great Boer War

The Great Boer War by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle

Goodbye Dolly Gray by Rayne Kruger

The Boer War by Thomas Pakenham

South Africa and the Transvaal War by Louis Creswicke (6 highly partisan volumes)

Books solely on the fighting in Natal:

Buller’s Campaign by Julian Symons

Ladysmith by Ruari Chisholm

For a view of the fighting in Natal from the Boer perspective:

Commando by Deneys Reitz.

67. Podcast on the Battles of Val Krantz and Pieters fought between 5th and 28th February 1900 in the Boer War: The third unsuccessful attempt by Buller to push across the Tugela River followed by the fourth, final and successful crossing of the Tugela, leading to the relief of Ladysmith: John Mackenzie’s britishbattles.com podcasts

67. Podcast on the Battles of Val Krantz and Pieters fought between 5th and 28th February 1900 in the Boer War: The third unsuccessful attempt by Buller to push across the Tugela River followed by the fourth, final and successful crossing of the Tugela, leading to the relief of Ladysmith: John Mackenzie’s britishbattles.com podcasts

The previous battle of the Great Boer War is the Battle of Val Krantz

The next battle of the Great Boer War is the Battle of Paardeberg