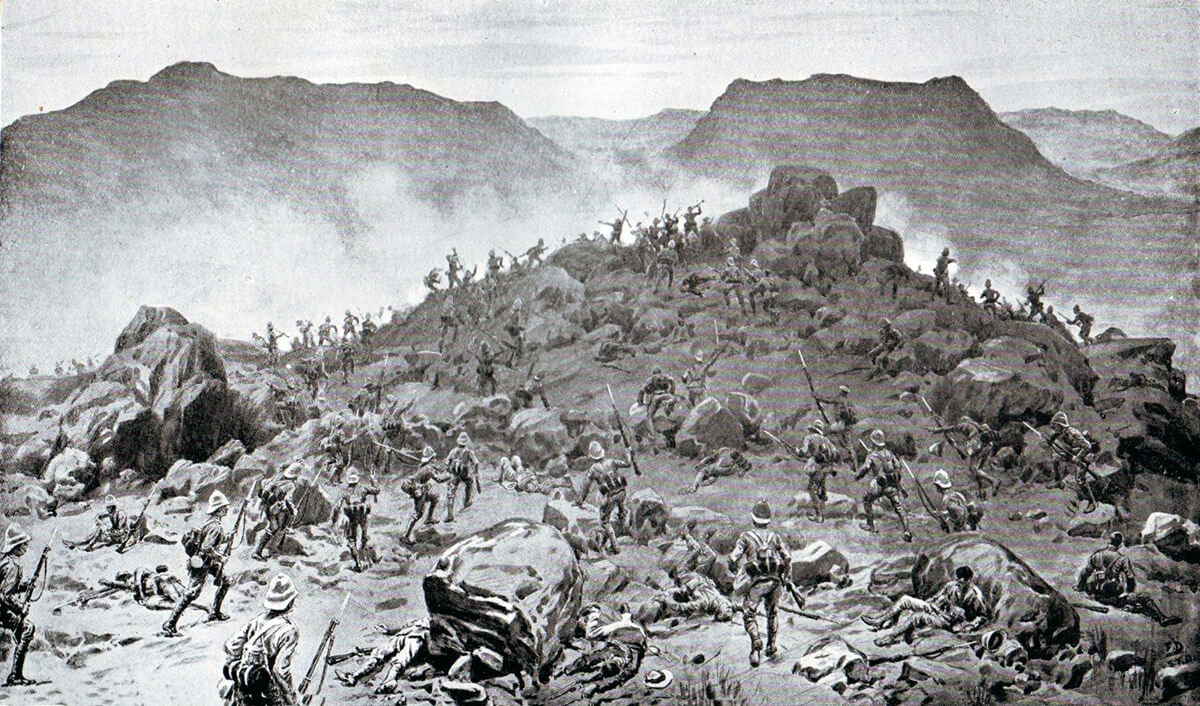

The battle, fought on 23rd November 1899 in the Great Boer War, beginning the British advance to relieve Kimberley, besieged by the Boers

Grenadier and Scots Guards storming the Boer positions at the Battle of Belmont on 23rd November 1899 in the Great Boer War

60. Podcast on the Battle of Belmont fought on 23rdNovember 1899 in the Boer War, beginning the British advance to relieve Kimberley, besieged by the Boers: John Mackenzie’s britishbattles.com podcasts

60. Podcast on the Battle of Belmont fought on 23rdNovember 1899 in the Boer War, beginning the British advance to relieve Kimberley, besieged by the Boers: John Mackenzie’s britishbattles.com podcasts

The previous battle in the Boer War is the Battle of Ladysmith

The next battle in the Boer War is the Battle of Graspan

Battle: Belmont

War: The Great Boer War

Date of the Battle of Belmont: 23rd November 1899.

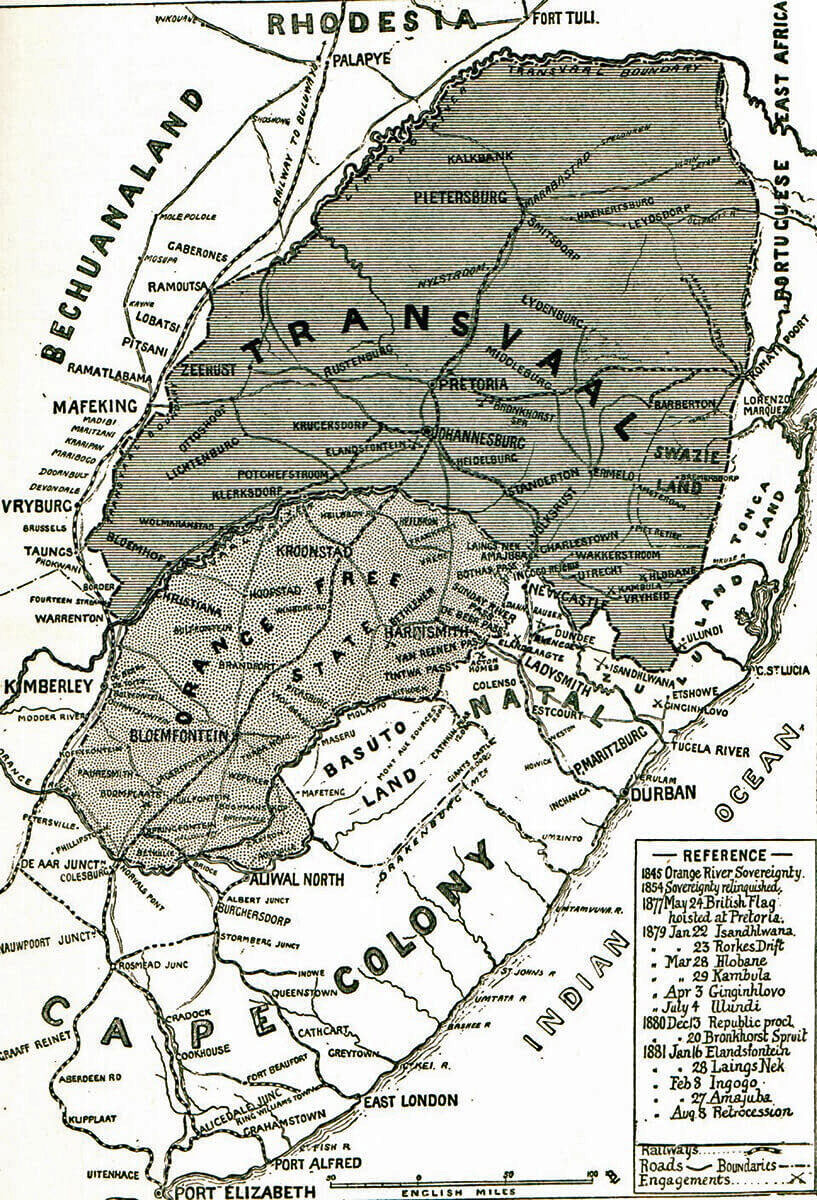

Place of the Battle of Belmont: On the western border of the Orange Free State, north west of Cape Colony in South Africa.

Combatants at the Battle of Belmont: British against the Boers.

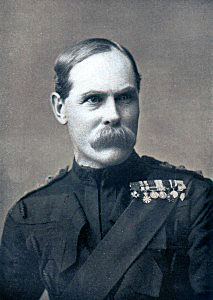

Lieutenant General Lord Methuen, commander of the British force at the Battles of Belmont and Graspan in November 1899 in the Great Boer War

Generals at the Battle of Belmont: Lieutenant General Lord Methuen against Commandant J. Prinsloo.

Size of the armies at the Battle of Belmont: 9,000 British against 2,000 Boers from the Transvaal and the Free State.

Uniforms, arms and equipment at the Battle of Belmont: The Boer War was a serious jolt for the British Army. At the outbreak of the war British tactics were appropriate for the use of single shot firearms, fired in volleys controlled by company and battalion officers; the troops fighting in close order. The need for tight formations had been emphasised time and again in colonial fighting. In the Zulu and Sudan Wars overwhelming enemy numbers armed principally with stabbing weapons were kept at a distance by such tactics, but, as at Isandlwana, would overrun a loosely formed force. These tactics had to be entirely rethought in battle against the Boers armed with modern weapons.

In the months before hostilities the Boer commandant general, General Joubert, bought 30,000 Mauser magazine rifles, firing smokeless ammunition, and a number of modern field guns and automatic weapons from the German armaments manufacturer Krupp, the French firm Creusot and the British company Maxim. Unfortunately for the Boers they elected to buy high explosive ammunition for their new field guns. The war was to show that high explosive was largely ineffective in the field, unless rounds landed on rocky terrain and splintered the rock. The British artillery relied upon air-bursting shrapnel which was highly effective against infantry in open country.

Once the war was under way the arms markets of Europe were no longer open to the Boers due to the British naval blockade and the error in ammunition selection could not be remedied.

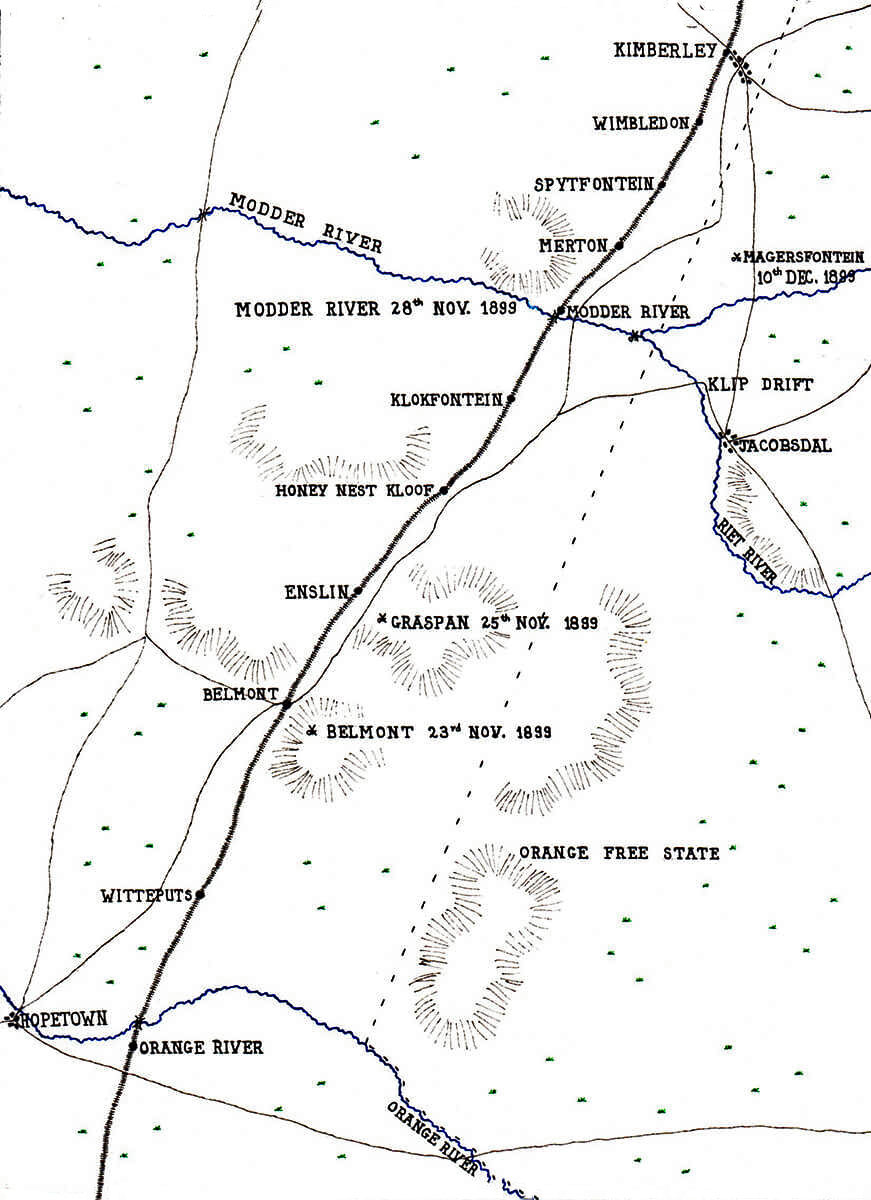

Map of South Africa: Methuen’s march took place up the left side of the map: Battles of Belmont and Graspan in November 1899 in the Boer War

The Boer Commandoes, without formal discipline, welded into a fighting force through a strong sense of community and dislike for the British. Field Cornets led burghers by personal influence not through any military code. The Boers did not adopt military formation in battle, instinctively fighting from whatever cover there might be. Most Boers were countrymen, running their farms from the back of a pony with a rifle in one hand. These rural Boers brought a life time of marksmanship to the war, an important advantage further exploited by Joubert’s consignment of smokeless magazine rifles. Viljoen is said to have coined the aphorism “Through God and the Mauser”. With strong field craft skills and high mobility, the Boers were natural mounted infantry. The urban burghers and foreign volunteers readily adopted the fighting methods of the rest of the army.

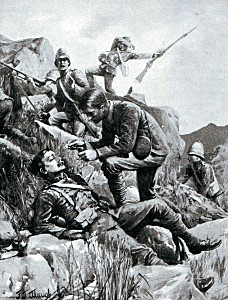

Battle of Belmont on 23rd November 1899 in the Great Boer War: an ‘imaginative’ contemporary illustration

Other than in the regular uniformed Staats Artillery and police units, the Boers wore their every day civilian clothes on campaign.

After the first month the Boers lost their numerical superiority, spending the rest of the formal war on the defensive against British forces that regularly outnumbered them.

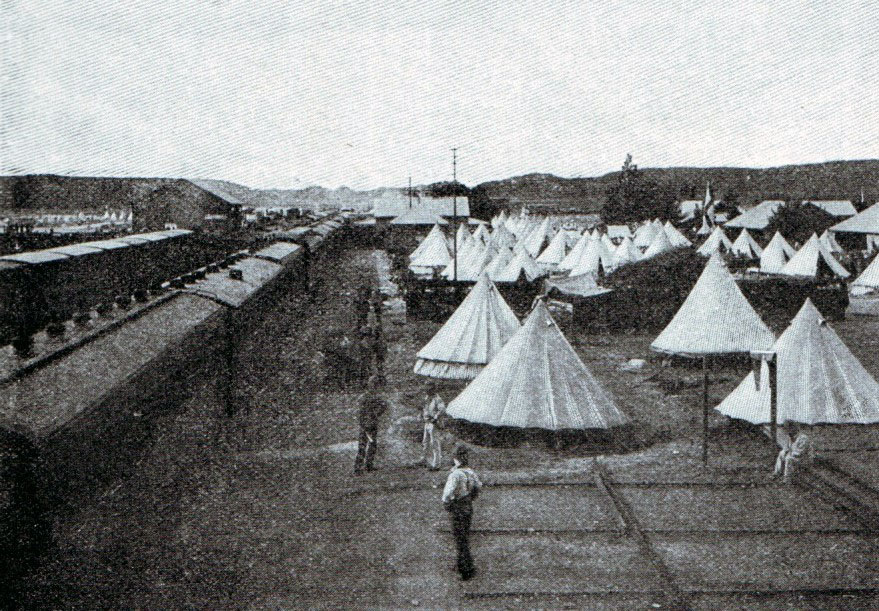

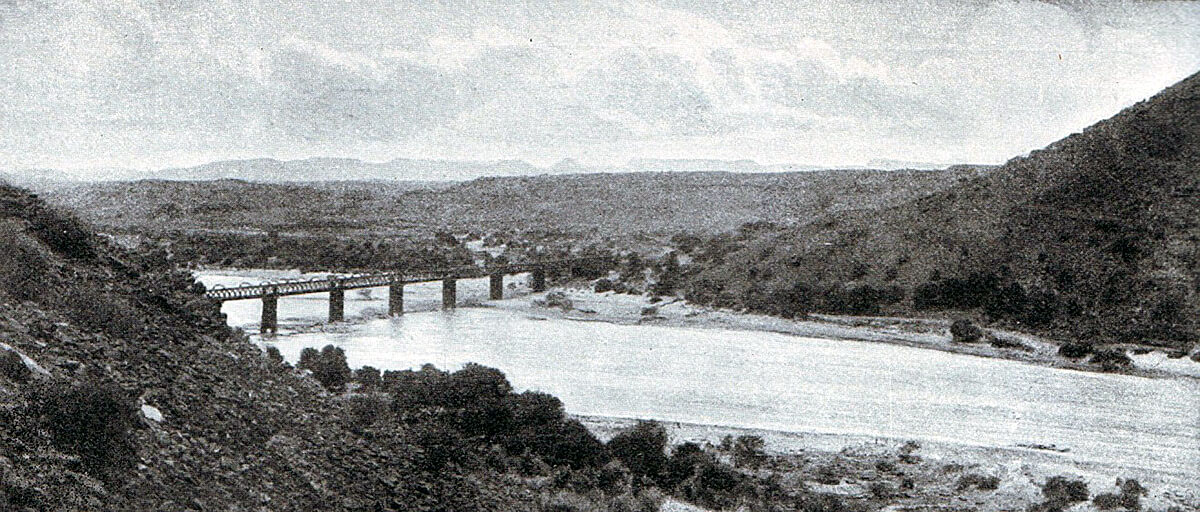

British depot camp at Orange River Bridge in 1899: Battle of Belmont on 23rd November 1899 in the Great Boer War

British tactics, developed on the North-West Frontier of India, Zululand, the Sudan and in other colonial wars against badly armed tribesmen, when used at Modder River, Magersfontein, Colenso and Spion Kop were incapable of winning battles against entrenched troops armed with modern magazine rifles. Every British commander made the same mistake; Buller; Methuen, Roberts and Kitchener (Elandslaagte was a notable exception where Hamilton specifically directed his infantry to keep an open formation). When General Kelly-Kenny attempted to winkle Cronje’s commandoes out of their riverside entrenchments at Paardeberg using his artillery, Kitchener intervened and insisted on a battle of infantry assaults, with the same high casualties as earlier in the war.

Orange River Railway Bridge where Lord Methuen’s force crossed the river forming the border between Cape Colony and the Boer Orange Free State: Battle of Belmont on 23rd November 1899 in the Great Boer War

Some of the most successful British troops were the non-regular regiments; the Imperial Light Horse, City Imperial Volunteers, the South Africans, Canadians, Australians and New Zealanders, who more easily broke from the habit of earlier British colonial warfare, using their horses for transport rather than the charge, advancing by fire and manoeuvre in loose formations and making use of cover, rather than the formal advance into a storm of Mauser bullets.

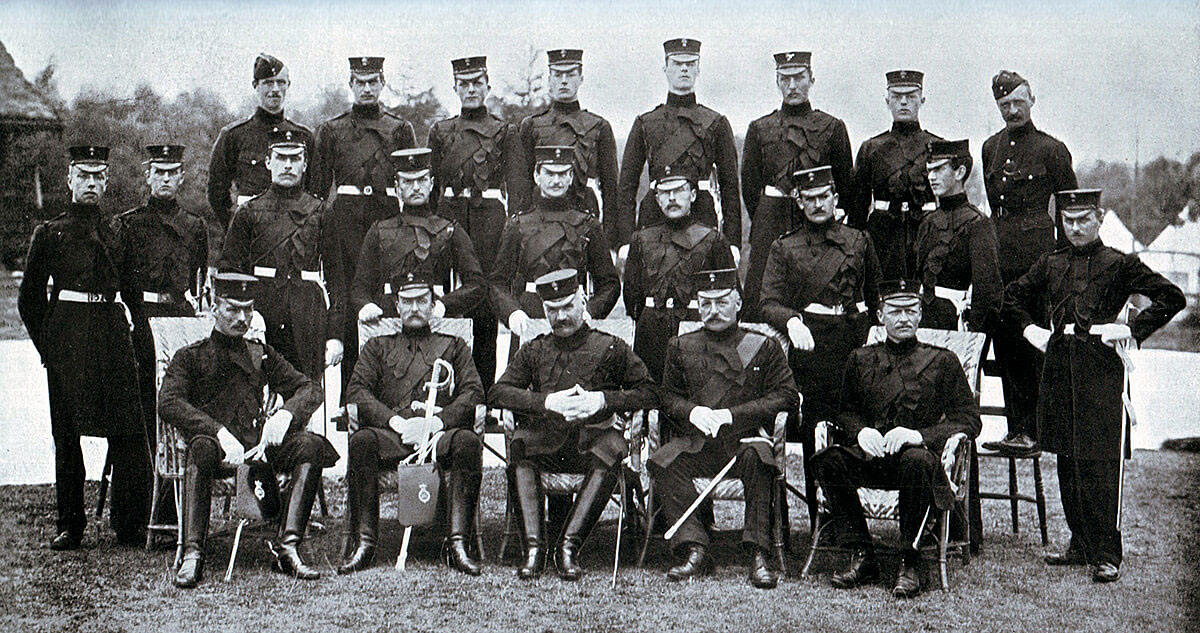

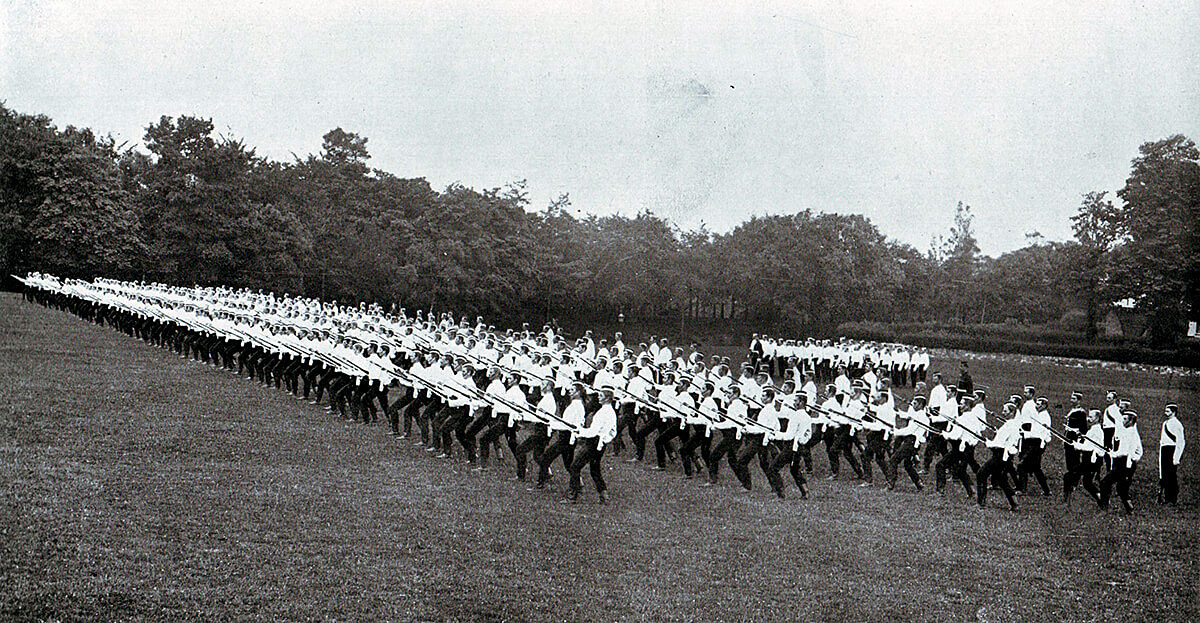

2nd Coldstream Guards at bayonet practice in Britain before leaving for South Africa in 1899: Battle of Graspan on 23rd November 1899 in the Great Boer War

War Aims:

Having started the hostilities, the Boers found themselves without an achievable war aim. The only strategy that might have had a chance of success would have been to invade and occupy the whole of Cape Colony, Natal and the other neighbouring British colonies.

The two Boer republics did not have the resources to carry out such an extensive operation. In any case they could not have prevented a British sea landing to retake the colonies.

Once war was declared, the Boers invaded and occupied Natal as far as the Tugela River, but with Ladysmith holding out in their rear. The Orange Free State government was not prepared to allow its forces to advance further south in Natal. In Cape Colony, some of the citizens of Boer origins joined their brothers from the two Republics, but most did not.

Map showing the area of Lord Methuen’s operations from the Orange River to the Battle of Magersfontein on 10th December 1899 in the Boer War: map by John Fawkes

The only other offensive operations the Boers carried out were to besiege Mafeking in the north and Kimberley near the Cape Colony border. Both sieges were unsuccessful and took up substantial Boer resources. Limited incursion was carried out into the central area of Cape Colony, up to the area around Stormberg.

The major difficulty for the Boer armies was that, although competent in defence, digging field fortifications and using their magazine rifles to great effect to defend them, the Boers lacked an effective offensive capability. The absence of formal military discipline made it difficult for the Boer commanders to devise strategies they could rely on their troops to carry out. As the British built up their armies and began to advance, defeat for the Boers became inevitable.

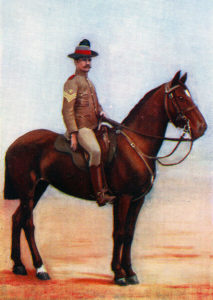

Sergeant Major of New South Wales Lancers in 1899. The regiment had its baptism of fire at the Battle of Belmont on 23rd November 1899 in the Great Boer War

Uniforms at the Battle of Belmont: British regiments made an uncertain change into khaki uniforms in the years preceding the Boer War, with the topee helmet as tropical headgear. Highland regiments in Natal devised aprons to conceal coloured kilts and sporrans. By the end of the war, the uniform of choice was slouch hat, drab tunic and trousers; the danger of shiny buttons and too ostentatious emblems of rank, emphasised in several engagements with disproportionately high officer casualties.

The British infantry were armed with the Lee Metford magazine rifle, firing 10 rounds. But no adequate training regime had been established to take advantage of the accuracy and speed of fire of the weapon. Personal skills such as scouting and field craft were little taught. The idea of fire and movement was largely unknown, many regiments still going into action in close order. Notoriously, General Hart insisted that his Irish Brigade fight shoulder to shoulder as if on parade in Aldershot. Short of regular troops, Britain engaged volunteer forces from Britain, Canada, Australia and New Zealand, who brought new ideas and more imaginative formations to the battlefield.

The British regular troops lacked imagination and resource. Routine procedures such as effective scouting and camp protection were often neglected. The war was littered with incidents in which British contingents became lost or were ambushed, often unnecessarily and forced to surrender. The war was followed by a complete re-organisation of the British Army, with emphasis placed on personal weapon skills and fire and movement, using cover.

Officer of the 9th Lancers, the sole British cavalry regiment at the Battle of Belmont 23rd November 1899 in the Great Boer War

The British artillery was a powerful force in the field, underused by commanders with little training in the use of modern guns in battle. Pakenham cites the Battle of Pieters as being the battle at which a British commander, surprisingly Buller, developed a modern form of battlefield tactics: heavy artillery bombardment, co-ordinated to permit the infantry to advance under its protection. It was the only occasion that Buller showed any real generalship and the short inspiration quickly died.

The Royal Field Artillery fought with 15 pounder guns; the Royal Horse Artillery with 12 pounders and the Royal Garrison Artillery batteries with 5-inch howitzers. The Royal Navy provided heavy field artillery with a number of 4.7-inch naval guns mounted on field carriages devised by Captain Percy Scott of HMS Terrible. The Royal Navy also fielded the 12 pounder guns seen in the Field Gun competition at the Royal Tournament.

Automatic weapons were used by the British, usually mounted on special carriages accompanying the mounted infantry or cavalry.

Winner of the Battle of Belmont: The British.

British Regiments at the Battle of Belmont:

9th Lancers, now 9th/12th Royal Lancers.

Royal Field Artillery: 18th and 75th Batteries.

Royal Engineers: 7th Field Company

Royal Army Medical Corps: 19th Field Hospital.

Army Service Corps

The Naval Brigade comprising Royal Navy, Royal Marine Light Infantry and four long 12 pounder guns (although called a brigade this unit comprised around 365 naval and marine personnel, a weak half-battalion)

Guards Brigade (Major General Colville)

3rd Battalion, Grenadier Guards.

1st and 2nd Battalions, Coldstream Guards.

1st Battalion, Scots Guards.

9th Brigade (Major General Featherstonehaugh and then Major General Pole-Carew)

1st Northumberland Fusiliers: now the Royal Regiment of Fusiliers.

2nd Manchester Regiment: later the King’s Regiment and now part of the Duke of Lancaster’s Regiment.

2nd King’s Own Yorkshire Light Infantry: later the Light Infantry and now part of the Rifles.

2nd North Lancashire Regiment: later the Queen’s Lancashire Regiment and now part of the Duke of Lancaster’s Regiment.

2nd Northamptonshire Regiment: now the Royal Anglian Regiment.

Rimington’s Guides.

New South Wales Lancers

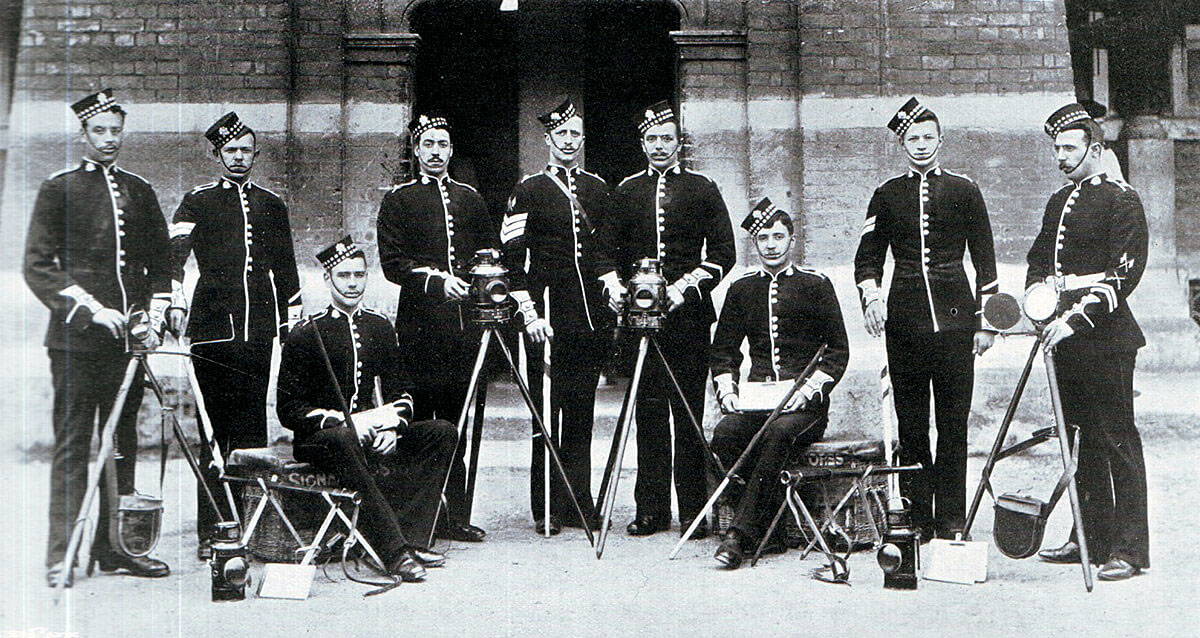

Sergeant Cunningham of Rimington’s Scouts: Battle of Belmont on 23rd November 1899 in the Great Boer War

Background to the Battle of Belmont:

The two Boer Republics, the Transvaal and the Orange Free State, began the war against Great Britain on 14th October 1899. Their principal operation was to invade Natal. They also began sieges of Mafeking and Kimberley, both important towns along the western borders of the two Boer republics.

The authorities in Great Britain prepared to send an Army Corps to South Africa under the command of Lieutenant General Sir Redvers Buller.

The three battles in Natal, Talana Hill on 20th October, Elandslaagte on 21st October and Ladysmith on 30th October 1899 saw the British force in Northern Natal under Lieutenant General Sir George White penned up in Ladysmith and put under siege by the Boers.

Buller arrived in Cape Town with the Army Corps and prepared his strategy for the war. Lord Methuen would command the force with the task of marching up the railway running north along the western border of the Boer Republics, to relieve Kimberley and eventually Mafeking. Lieutenant General Gatacre would command in the central front.

Sir George White, the British commander-in-chief in Natal, was under siege in Ladysmith, so a general fell to be appointed to command the relief force in Natal. Buller took this role on himself, leaving the overall strategy of the war with no guiding hand.

Buller expected it would take him two weeks to relieve the Ladysmith garrison, after which he would return to Cape Colony. Buller was to spend the rest of the active war crossing the Tugela River and relieving Ladysmith.

Eventually the British government sent a strong command team of Lord Roberts and General Kitchener to take over the offensive in the Orange Free State from Cape Colony. Until Roberts and Kitchener reached South Africa, Lord Methuen was left to command the only advance on the Boer Republics.

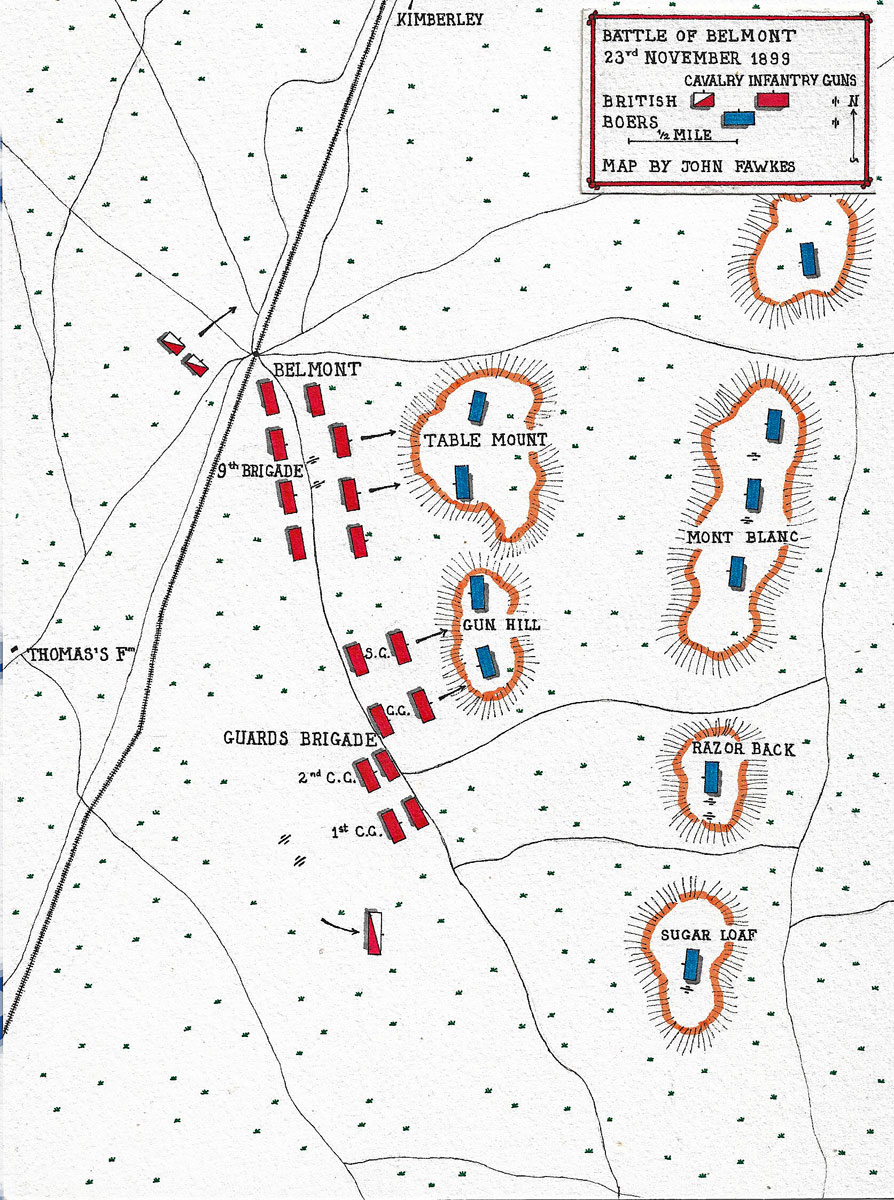

Map of the Battle of Belmont, fought on 23rd November 1899 in the Great Boer War: battle map by John Fawkes

Account of the Battle of Belmont:

Lieutenant General Lord Methuen landed at Cape Town on 10th November 1899. His task with his division was to force his way north up the route of the Cape Town to Bulawayo Railway and raise the Boer siege of Cecil Rhodes’s diamond town, Kimberley.

The British authorities feared that a Boer capture of Kimberley would considerably increase the financial resources available to the Boer republics through access to Kimberley’s diamond mines.

The forward base for Methuen’s force was already established at De Aar in the north of Cape Colony, approximately 60 miles from the Orange River, forming the border with the Orange Free State. Substantial quantities of supplies were stock piled at De Aar for his use.

At Orange River Bridge were the 9th Lancers, Rimington’s Guides, 1st Northumberland Fusiliers, 1st Royal Munster Fusiliers, a battery of the RFA and an armoured train.

On 10th November 1899, Colonel Gough led a mounted force north, to a point 9 miles east of Belmont. An action took place, supported by British infantry brought forward by train from Orange River station. It ended with a hurried British withdrawal, in the face of a larger than expected Boer force.

A lesson from this action was that the British officers were too conspicuous and must dress and arm more like their soldiers to avoid unnecessary officer casualties.

Lord Methuen arrived in De Aar and was ready to move out on 20th November 1899.

Lord Methuen commanded a force comprising two infantry brigades, the Guards Brigade (3rd Grenadiers, 1st and 2nd Coldstream and 1st Scots Guards, also the Naval Brigade; Royal Navy personnel, sailors and Royal Marines from HMS Doris and Powerful) and the 9th Brigade (parts of 1st Northumberland Fusiliers, 1st Manchester Regiment, 2nd King’s Own Yorkshire Light Infantry, 2nd Northamptonshire Regiment and half of 1st Loyal North Lancashire Regiment), and two batteries of Royal Field Artillery, 18th and 75th Batteries with twelve guns and four Royal Navy long 12 pounders manned by sailors from HMS Doris.

British troops camping on the Veldt during Methuen’s march to relieve Kimberley: Battle of Belmont on 23rd November 1899 in the Great Boer War

Sergeant of 1st Scots Guards saying ‘Good Bye’ to his mother before leaving for South Africa in 1899: Battles of Belmont and Graspan in November 1899 in the Boer War

Methuen’s cavalry comprised two squadrons of 9th Lancers, 100 Rimington’s Guides and some mounted infantry.

Methuen’s force comprised around 7,500 infantry, 16 guns with their gunners and around 500 mounted men, in all around 9,000 men.

Intelligence reports suggested that the Boer forces facing Methuen in his advance to Kimberley were ‘weak in numbers, ill-organised and of low fighting capacity’. Methuen was advised that his advance to Kimberley would be scarcely contested. This assessment proved to be completely wrong.

Methuen resolved to march as light as possible. Baggage and stores were cut down and officers were not permitted to take tents. The battalions were to march without bugle or drum to keep noise to a minimum.

The column stood to arms at midnight on the night of 20th/21st November, the intention being to march at night to avoid the heat of the day. For some reason the order to march was not given until after 2.30am. The cavalry, Guards Brigade and artillery led the column followed by the 9th Brigade.

The first day’s march was ten miles to Fincham’s Farm. The sun rose and was fiercely hot. There was no water available, other than that carried in the containers. The route was across open sandy veldt with no natural cover. Nothing was seen of the Boers, although Boer scouts were keeping track of the British.

The British column halted for the night at Fincham’s Farm. A party of 9th Lancers and Rimington’s Guides rode on to Thomas’s farm at Belmont, coming under fire on the way, where they again came under fire and returned to the main body.

Grenadier Guards storming the Boer positions at the Battle of Belmont on 23rd November 1899 in the Great Boer War: picture by Frank Dadd

On 22nd November 1899, Methuen’s division marched out for the next halt at Belmont. The route was again north, following the railway line.

Drums and Colours of 2nd Coldstream Guards: Battles of Belmont and Graspan in November 1899 in the Boer War

As the troops marched into the camp site at Belmont, it was known that the Boers were in position to the east and there would be a fight the next day.

Some four miles to the east of Belmont and running approximately parallel with the railway line lay a line of kopjes or hills, running roughly north-west to south-east. The Boers were occupying these kopjes, Table Hill to the north and Gun Hill in the centre. Behind these two kopjes lay a higher line of kopjes. In the centre of this line was a deep nek with a kopje called Mont Blanc to its north and to its south Razor Back and Sugar Loaf Hill. The Boers were positioned on all these high points.

The British transport was still on the road from Orange River, so there was little for the troops to eat that night.

New South Wales Lancers covering the withdrawal of the 9th Lancers at the Battle of Belmont on 23rd November 1899 in the Great Boer War

Methuen planned an attack in the pre-dawn darkness on the Boer positions. The 9th Brigade was to attack Table Hill, the northern feature, while the Guards attacked Gun Hill. Each brigade was to be supported by an artillery battery. Both these attacks were intended to be flanking movements. Two squadrons of 9th Lancers with a company of Mounted Infantry were to march north from Belmont station and move in a wide arc round to the rear of the Boer positions. A further detachment of mounted troops was to advance on the right flank of the infantry line. The guns were to cover the advance with a shrapnel barrage on the Boer positions.

The troops marched out at around 3am on 23rd November, well after the intended start time of 1.30am. The 9th Brigade advanced on Table Hill, 1st Northumberland Fusiliers on the left, 1st Northamptonshires on the right and 2nd King’s Own Yorkshire Light Infantry and two companies of Royal Munster Fusiliers (just arrived) in reserve.

The Guards Brigade on the right moved towards Gun Hill, 3rd Grenadiers on the right, 1st Scots Guards on the left, with the two Coldstream battalions in reserve, to the right of the forward line. In the darkness of the early morning, the Guards line moved to the right, losing the essence of a flank attack and committing the troops to a frontal assault on the Boer positions.

The wire fence along the railway line, which was in the way of the advance, was cut using axes, as no wire cutters were on issue to the troops. Alarmed wild animals were put up, as the British troops marched forward. It was feared that the noise must warn the Boers of the impending attack on them. In fact, the Boer commanders, without carrying out proper surveillance of the advancing British force, assumed it was still at Freeman’s Farm awaiting its transport.

The dawn came at around 4am. The British line had advanced around four miles, but was still some distance from the Boer positions. Both brigades were marching across open veldt, when the rising sun showed the Boers the threat to their positions. They opened a heavy fire on the advancing British infantry.

The two leading Guards battalions, 3rd Grenadiers and 1st Scots Guards went to ground and fired volleys at the Boer positions for around half an hour, while the 9th Brigade continued to scale Table Hill on their left.

At 4.30am the two batteries came up and went into action, shelling the Boer positions with shrapnel. The Guards continued with their advance and in the face of a heavy but largely ineffective fire stormed the hill.

The Boers on Table Hill and Gun Hill did not wait for the final bayonet attack, but hurried away down the far hillside to where their ponies were tethered and rode back to join their comrades on the next line of kopjes; Mont Blanc, Razor Back and Sugar Loaf. By the time the British infantry reached the top of the hills, the Boers were gone.

British troops removing the dead from the battlefield after the Battle of Belmont on 23rd November 1899 in the Great Boer War

The British artillery opened a barrage on the Boer second line, which was answered by the Boer guns and continued for an hour and a half.

At about 5.45am the British resumed the advance. The Grenadiers and Scots Guards headed straight up Mont Blanc, with much of the 9th Brigade coming down off Table Hill in behind the two Guards battalions.

The two Coldstream battalions moved further to the right and stormed the Boer positions on Razor Back and Sugar Loaf Hills. Some companies of Coldstreamers put in an attack on the extreme left of the line.

Again, once the attacking British infantry reached the summits of the hills, the Boers jumped on their ponies and raced away, bringing the battle to an end. One or two further positions were occupied by small parties of Boers and cleared by the British, but broadly the battle was ended.

The inadequate numbers of British cavalry precluded any effective pursuit, the 9th Lancers having been forced to withdraw to the area of Belmont after attempting an incursion around the Boer right flank.

Casualties at the Battle of Belmont:

British casualties were 75 officers and soldiers killed and 223 wounded.

Boer casualties were said to have been 83 killed, 20 wounded and 30 captured, including a German artillery commandant and 6 field cornets.

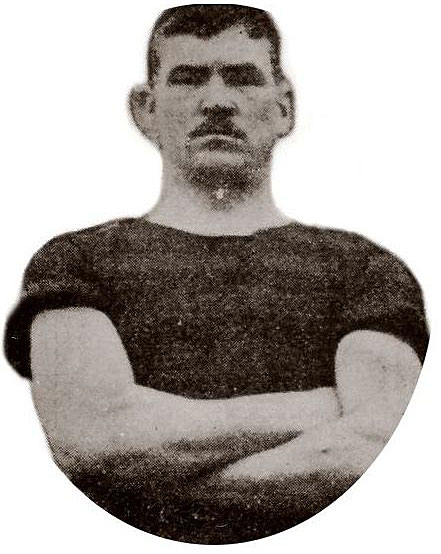

Private Dai St John 3rd Battalion Grenadier Guards bayoneting Boers at the Battle of Belmont on 23rd November 1899 in the Great Boer War. St John was shot dead soon afterwards. St John was a champion Welsh Boxer. Picture by Albert Morrow

Follow-up to the Battle of Belmont:

Methuen’s force continued its advance with the Battle of Graspan taking place on 25th November 1899.

Anecdotes and traditions from the Battle of Belmont:

- Following the loss of officers in the initial action north of the Orange River, officers were required to reduce their profile by dulling their buttons and accoutrements and where possible to carry rifles, in line with their soldiers.

- The Welsh champion boxer Dai St John was a soldier in 3rd Grenadier Guards. St John was a 6 foot 3 inches 28-year-old ex-Welsh Miner who joined the Army when his boxing career faltered. At Belmont he is said to have led his company up Gun Hill and killed several Boers with the bayonet. Struggling to remove the bayonet from his final victim St John was shot in the head and killed. St John was a veteran of the Battle of Omdurman.

- The commander of the 9th Brigade, General Featherstonehaugh, during the Battle of Belmont rode up and down in the front of his brigade’s line with his staff. This had the effect of drawing fire on his party and masking his own men’s fire. Eventually a soldier of the 9th Brigade shouted out ‘**** thee, get thee to **** and let us fire’. Featherstonehaugh was shot and severely wounded.

- Reverend Eustace St Clare Hill attached to the 9th Brigade insisted on entering the firing line at Belmont and administering the last rites to wounded soldiers. An officer remonstrated with him and he replied ‘This is my place and I am doing my special business.’ Hill, educated at Lancing and Christchurch, Oxford, was a civilian clergyman in Grahamstown until he joined Lord Methuen’s army, serving through the Boer War. Hill settled in South Africa and accompanied the South African forces to France in the First World War. Hill lost an arm at Delville Wood and was awarded the Military Cross, before returning to South Africa.

- Several incidents of Boers raising a white flag and continuing to fight were recorded at Belmont and at Graspan. Colonel Crabbe and Lieutenant Willoughby of the 3rd Grenadiers are said to have been wounded after white flags had been raised. Lieutenant Blundell, also of the Grenadiers, stopped to give water to a wounded Boer who then shot him.

- Methuen was criticised for conducting a frontal attack at Belmont. Armchair tacticians in Britain said he should have enveloped the Boer positions by marching around each end.

Contemporary propaganda picture of the Battle of Belmont. There were no Scottish regiments present except the Scots Guards who did not wear the kilt: Battle of Belmont on 23rd November 1899 in the Great Boer War

References for the Battle of Belmont:

The Boer War is widely covered. A cross section of interesting volumes would be:

The Times History of the War in South Africa

The Great Boer War by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle

Goodbye Dolly Gray by Rayne Kruger

With the Flag to Pretoria by HW Wilson

The Boer War by Thomas Pakenham

South Africa and the Transvaal War by Louis Creswicke (6 highly partisan volumes)

![]() 60. Podcast on the Battle of Belmont fought on 23rdNovember 1899 in the Boer War, beginning the British advance to relieve Kimberley, besieged by the Boers: John Mackenzie’s britishbattles.com podcasts

60. Podcast on the Battle of Belmont fought on 23rdNovember 1899 in the Boer War, beginning the British advance to relieve Kimberley, besieged by the Boers: John Mackenzie’s britishbattles.com podcasts

The previous battle in the Boer War is the Battle of Ladysmith

The next battle in the Boer War is the Battle of Graspan