The account of General Braddock’s expedition to Fort Duquesne in 1755:

Part 11: The 2nd Earl of Albemarle, the Duke of Cumberland and Edward Braddock’s expedition to capture Fort Duquesne in 1755.

William Augustus, Duke of Cumberland: Death of General Edward Braddock on the Monongahela River on 9th July 1755 in the French and Indian War

The previous section on Braddock’s defeat on the Monongahela in 1755 is Part 10: Braddock’s final battle on 9th June 1755.

The next battle in the British Battles series is the Battle of Ticonderoga

To the French and Indian War index

This section considers the involvement of the 2nd Earl of Albemarle in the devising and planning of Edward Braddock’s expedition to capture Fort Duquesne in 1755.

Arnold Joost van Keppel, 1st Earl of Albemarle: picture by Sir Godrey Kneller: Death of General Edward Braddock on the Monongahela River on 9th July 1755 in the French and Indian War

Willem Anne van Keppel, 2nd Earl of Albemarle:

The 2nd Earl of Albemarle (5 June 1702 – 22 December 1754) was an English nobleman of great influence. His father, Arnold Joost van Keppel, 1st Earl of Albemarle, was a close confidant of the Dutch King William III of Britain, achieving great wealth and high position at court and, after King William’s death, becoming a general in the Dutch army, fighting at the important battles of Ramillies and Oudenarde under the Duke of Marlborough. King William III left the 1stEarl of Albemarle £200,000 in his will, an enormous sum at the time and an estate in Holland.

Willem Anne van Keppel, Viscount Bury, son of the 1st Earl of Albemarle, referred to hereafter as ‘Lord Albemarle’, was born in 1702 and christened with Queen Anne as his godmother, the Queen giving him his second name.

In 1717, at the age of 15, Lord Albemarle received a commission as Captain of the Grenadier Company in the Coldstream Regiment of Foot Guards, a significant mark of Royal favour. His father died in 1718 and Albemarle became the 2nd Earl of Albemarle with an estate in Holland and considerable wealth.

In adulthood, Lord Albemarle was on the closest terms with King George II and his second son, William Augustus, Duke of Cumberland.

Willem Anne van Keppel, 2nd Earl of Albemarle ‘Lord Albemarle’: Death of General Edward Braddock on the Monongahela River on 9th July 1755 in the French and Indian War

In 1722, at the age of 20, Lord Albemarle was appointed Groom of the Bedchamber to King George II, a personal appointment made to the King’s close associates.

In 1723, Lord Albemarle married Lady Anne Lennox, daughter of the Duke of Richmond, illegitimate son of King Charles II and an important nobleman.

In 1725, Lady Albemarle was appointed Lady of the Bedchamber to Queen Caroline, a position she held until the Queen died in 1737. Lady Albemarle was a confidante of the Countess Yarmouth, King George II’s Hanoverian mistress, a woman of considerable influence over the King, particularly after the death of Queen Caroline.

Also in 1725, the Duke of Cumberland was commissioned into the Army, being appointed major-general and colonel of Lord Albemarle’s regiment, the Coldstream Guards.

In 1725, Lord Albemarle was appointed Knight of the Bath.

In 1727, Lord Albemarle was appointed aide-de-camp to King George II.

In 1731, Lord Albemarle bought the colonelcy of the 29th Regiment of Foot, from being captain in the Coldstream. In 1733, he bought the colonelcy of the Third Troop of Horse Guards, a position of importance only open to senior officers in royal favour.

In 1737, on the death of Lord Orkney, Lord Albemarle was appointed Governor of Virginia, a post he held for the rest of his life, without crossing the Atlantic and visiting the colony.

In 1739, Lord Albemarle was promoted brigadier-general, at the age of 37.

In 1742, both Lord Albemarle and the Duke of Cumberland were appointed to command in the British force sent to Flanders, to fight for the Empress Marie-Theresa. Lord Albemarle was promoted to the rank of major-general, being 40 years old.

Anne, 2nd Countess of Albemarle in later life: Death of General Edward Braddock on the Monongahela River on 9th July 1755 in the French and Indian War

From 1743 to 1747, Lord Albemarle and the Duke of Cumberland served together on the Continent and in Scotland. At the Battle of Dettingen in 1743, at which King George II was present, the Duke of Cumberland was seriously wounded, while Lord Albemarle had his horse shot under him.

In 1745, the Duke of Cumberland was appointed Captain-General of the British Army, a position left unfilled since the dismissal of the Duke of Marlborough in 1711.

At the Battle of Fontenoy in 1745, Lord Albemarle was one of the senior commanders of the columns of foot that the Duke of Cumberland led into the attack and was wounded.

With the outbreak of the Jacobite rebellion in 1745, Lord Albemarle was given command of the force of Dutch and British troops brought back from Flanders to join Marshal Wade’s army at Newcastle.

At the Battle of Culloden on 16th April 1746 (OS), where the Duke of Cumberland led the royal army to victory over the Jacobite rebels, Lord Albemarle commanded the first line of foot.

After spending a year as commander-in-chief in Scotland, Lord Albemarle returned to Flanders with the Duke of Cumberland and held a senior command at the Battle of Lauffeldt in 1747.

At every important event in the Duke of Cumberland’s military career between 1742 and 1748, Lord Albemarle was at his side.

Until his disgrace, following defeat at the Battle of Hastenbeck and the publicly reviled Convention of Kloster Zeven in 1757, the Duke of Cumberland was the supreme decision maker in the British Army, subject only to King George II and a leading influence in British political circles. Lord Albemarle was one of his closest friends and associates, if not his closest.

On the signing of the Treaty of Aix la Chapelle in 1748, bringing the war between France and Britain to an end, King George II appointed Lord Albemarle as his ambassador to the French Court at Versailles. This was an important and sensitive post, involving, in addition to the diplomatic functions, the monitoring of Jacobite activity in France.

King George II: Death of General Edward Braddock on the Monongahela River on 9th July 1755 in the French and Indian War

Other honours followed for Lord Albemarle: Knight of the Garter in 1750, Groom of the Stole, a senior post among the King’s personal attendants, in 1751 and, in the same year, appointment as a Privy Councillor, the Privy Council being the most influential permanent body of advisers to the King.

Lord Albemarle was a keen owner of race horses, another bond with the Duke of Cumberland, who was one of the principal founders of the Jockey Club in 1750. Both men kept stocks of horses for breeding and racing.

The close ties between Lord and Lady Albemarle and the Royal Family extended to their children.

In 1750, their second son, Captain Augustus Keppel of the Royal Navy, obtained from the Mediterranean for the Duke of Cumberland the Arab horses that became the Windsor Stud.

Their eldest son, Viscount Bury, commissioned into the Coldstream Guards in 1738, was appointed aide-de-camp to the Duke of Cumberland in 1745 and to King George II in 1746, before becoming colonel of the Twentieth Foot in 1749.

In 1761, on the Duke of Cumberland’s recommendation, the Government appointed Lord Bury, by then the 3rd Earl of Albemarle, following his father’s death in 1754, to command the military expedition to capture Havana. Whilst overseas, the 3rd Earl of Albemarle’s mistress and two children were accommodated at the Duke of Cumberland’s residence of Windsor Lodge. On his return home, the 3rd Earl of Albemarle became the Duke of Cumberland’s confidential secretary and, on the Duke’s death in 1765, the administrator of the Duke’s estate.

Significantly, all papers that might have compromised the Duke’s reputation were destroyed at the direction of King George III, the Duke’s nephew.

During his life and particularly during the period 1742 to his death in 1754, Lord Albemarle was of considerable influence in England, through his close relationship with the Duke of Cumberland and King George II.

Lord Albemarle was known to his contemporaries as ‘the spendthrift earl’. Despite the well-paid offices he enjoyed, Lord Albemarle died, in Paris in 1754, impecunious and with enormous debts.

Perhaps a single episode serves to illustrate Lord Albemarle’s style of life. When Lord Albemarle joined the Pragmatic Army in Flanders in 1747, his personal ‘equipage’ comprised some sixty horses.

Captain Augustus Keppel, Royal Navy: Death of General Edward Braddock on the Monongahela River on 9th July 1755 in the French and Indian War

Horace Walpole devoted a page to Lord Albemarle in his ‘Memoirs of the Reign of King George II’ (vol I page 82) saying: ‘The British Minister at Paris, Lord Albemarle, was not a man to offend the haughtiness of That Court, or the pusillanimity of his own, by mixing more sturdiness with his Memorials than he was commissioned to do. It was convenient to him to be anywhere but in England: his debts were excessive, though he was Embassador, Groom of the Stole, Governor of Virginia, and Colonel of a regiment of Guards. His figure was genteel, his manner noble and agreeable: the rest of his merit, for he had not even an estate, was the interest my Lady Albemarle had with the King through Lady Yarmouth (the King’s Hanoverian mistress), and his son, Lord Bury, being the Duke’s chief favourite. He had all his life imitated the French manners, till he came to Paris, where he never conversed with a Frenchman; not from partiality to his own countrymen, for he conversed as little with them, living entirely with a Flemish Columbine, that he had brought from the Army. If good breeding is not different from good sense, Lord Albemarle, who might have disputed even that maxim, at least knew how to distinguish it from good nature. He would bow to his postilion, while he was ruining his taylor.’

And (vol i page 422): ‘At the conclusion of the year (1754) deceased two men in great offices, whose deaths made remarked what their lives might have done; how little they were worthy of their exaltation. The one, Lord Gower, Lord Privy Seal, had indeed a large fortune, and commanded boroughs. Lord Albemarle, the other, died suddenly at Paris, where his mistress sold him to that Court. Yet the French Ministry had little to vaunt; while they were purchasing the instructions of our Embassador, attentive only to acquire the emptiest of their accomplishments….’

Skrine devotes a page note to Lord Albemarle in his book on the Battle of Fontenoy saying: ‘Stanhope (History of England vol iii, chap xxxii) hints that he sold Government secrets to a French mistress while ambassador in Paris. Casanova tells us that this lady’s nickname was “Lolotte”. That she utterly ruined him admits of no doubt.’

George Keppel, 3rd Earl of Albemarle: Death of General Edward Braddock on the Monongahela River on 9th July 1755 in the French and Indian War

There is the story that Lord Albemarle’s mistress one night expressed admiration for the stars and Lord Albemarle chided her as he was unable to buy them for her, with the implication that he bought everything else.

The more precisely expressed allegation is that Lord Albemarle’s Flemish mistress, while in Paris, sold British government dispatches to the French.

Lord Chesterfield wrote of Lord Albemarle to his son Philip Stanhope, an attaché in the British Embassy in Paris: ‘Between you and me, what do you think made our friend Lord Albemarle Colonel of a regiment of Guards, Governor of Virginia, Groom of the Stole, and Ambassador to Paris; amounting in all to sixteen or seventeen thousand pounds a year? Was it birth? No, a Dutch gentleman only. Was it his estate? No, he had none. Was it his learning, his parts, his political abilities and application? You can answer these questions as easily and as soon as I can ask them. What was it then? Many people wondered, but I do not; for I know, and will tell you. It was his air, his address, his manners, and his graces. He pleased, and by pleasing became a favourite, and becoming a favourite, became all that he has been since. Show me one instance where intrinsic worth and merit, unassisted by exterior accomplishments have raised any man so high.’

Lord Albemarle’s conduct of his affairs, particularly in the period 1748 to 1754, while he was British Ambassador in Paris, gave rise to the wildest of allegations against him. What is apparent is that his concern with breeding horses – an important shared interest with the Duke of Cumberland – gaming, but above all the maintenance of a lifestyle well beyond his means caused Lord Albemarle to be constantly and deeply in debt.

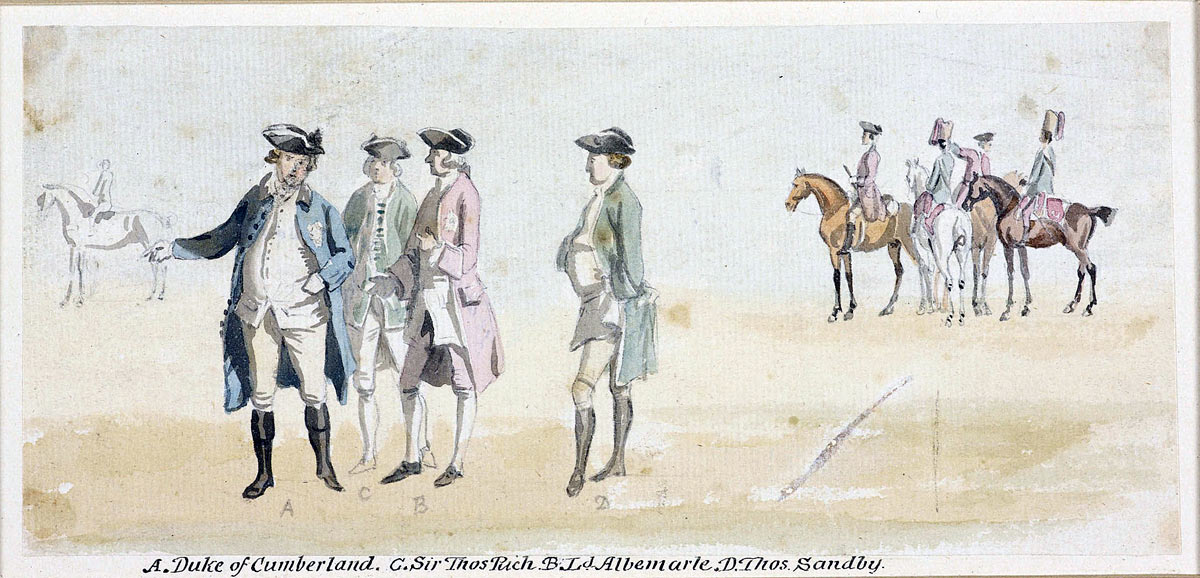

Duke of Cumberland, Sir Robert Rich and Lord Albemarle watching one of the Duke’s horses in training. The artist Thomas Sandby is on the right: picture by Thomas Sandby: Death of General Edward Braddock on the Monongahela River on 9th July 1755 in the French and Indian War

Lord Albemarle and the governorship of Virginia:

In 1737, William Gooch had been lieutenant-governor of Virginia for ten years. Gooch had the expectation that he would be appointed governor on the death of the Earl of Orkney, the previous governor, but the appointment went to Lord Albemarle.

From the appointment of Lord Albemarle as governor, it was a complaint of William Gooch that London took over the appointment of Virginia officials, to the detriment of Gooch’s influence in the colony.

Lord Albemarle saw his appointment as governor of Virginia as an opportunity to increase his income. He required appointees to administrative positions in the colony to pay him a fee and a percentage of their salary. This is unlikely to have applied to William Gooch, who was already in post when Lord Albemarle became governor, but it is well established that Robert Dinwiddie was required to pay three quarters of his salary, an annual sum of £3,000, to Lord Albemarle, to procure the post of lieutenant-governor of Virginia in 1751.

Lord Charles Hay of the First Foot Guards challenges the Gardes Francaises at the Battle of Fontenoy on 30th April 1745: picture by Edouard Detaille

The notorious ‘pistolet fee’ controversy, in which Robert Dinwiddie became embroiled as lieutenant-governor of Virginia arose from his need to increase his own income and probably to increase the income of the governor.

Lord Albemarle states in a letter in his official letter book that he was in regular correspondence with the lieutenant-governor of Virginia on affairs in the colony.

It is likely that Lord Albemarle possessed a good working knowledge of the politics and affairs of North America. He will have increased this knowledge, once he was appointed British Ambassador to Paris in 1748, with information gleaned from the French.

It was Lord Albemarle’s intervention in 1754 that obtained the release of American traders arrested by the French in the Ohio-Allegheny River region.

William Gooch, lieutenant-governor of Virginia from 1727 to 1749: Death of General Edward Braddock on the Monongahela River on 9th July 1755 in the French and Indian War

When Robert Dinwiddie secured the nomination for lieutenant-governor of Virginia, he had been a member of the Ohio Company for some months (see Braddock Part 1 and Braddock Part 2 for an account of the setting up and aims of the Ohio Company).

Lord Albemarle will have known of the affairs of the Ohio Company and the grant of land at the Ohio Forks made to it, following the Privy Council proceedings in 1748. Lord Albemarle was himself a Privy Councillor from 1751.

It would seem likely that Dinwiddie used the lure of the Ohio Company and the profits it was expected to make from the land grant at the Ohio Forks to entice Lord Albemarle into granting him the position of lieutenant-governor of Virginia.

It is entirely consistent with Dinwiddie’s urge to be appointed lieutenant-governor of Virginia and Lord Albemarle’s pressing need for money that Dinwiddie would have offered to ensure that Lord Albemarle became a beneficial member of the Ohio Company, with his involvement concealed through his membership being in the name of Robert Dinwiddie. It may well be that the Ohio Company entered into a confidential arrangement, written or agreed orally, to pay Lord Albemarle a commission on its profits.

Robert Dinwiddie lieutenant-governor of Virginia 1751 to 1758: portrait by an unknown artist: Death of General Edward Braddock on the Monongahela River on 9th July 1755 in the French and Indian War

In addition, Dinwiddie will have been keenly aware of the advantage of having Lord Albemarle as a party closely interested in the future of the Ohio Company.

In 1754, the Ohio Company submitted its additional petition to the Privy Council for an extended and more closely defined grant of land at the Ohio Forks. By this time, Lord Albemarle was himself a Privy Councillor.

Even if Lord Albemarle was not a member of the Ohio Company and there is no direct evidence that he was, as governor of Virginia, he is likely to have been aware that the Ohio Company comprised influential citizens of Virginia and it was likely to be in the financial interests of Virginia for the London government to grant the company’s petitions for grants of land at the Ohio Forks.

The military expedition to America:

When the Duke of Newcastle’s administration made the initial arrangements for the military expedition to America in 1754, the choice of commander-in-chief was Horatio Sharpe, governor of Maryland. The troops to be used were to be raised in the American colonies. The form of the expedition was to be left to the commander-in-chief, the goal being to repel the French threat.

Very quickly, King George II referred the government to the Duke of Cumberland for his ‘advice’. The Duke of Cumberland proposed that Lord Albemarle be made viceroy in America and command the military expedition.

This would appear to have been an attempt by the Duke of Cumberland to arrange an ambitious preferment for his close friend and associate, Lord Albemarle. The proposal was rejected by King George II.

The Duke of Cumberland went on to impose on the British Government a scheme for military action against the French in North America that, while if successful would significantly rein in French ambitions, was devised to further the interests of Virginia and Lord Albemarle.

A British infantryman of the 1750s: Death of General Edward Braddock on the Monongahela River on 9th July 1755 in the French and Indian War

Objections to the Duke of Cumberland’s plan:

If the interests of the British colonies in America required war to be waged against the French, those interests dictated that the war be conducted in New York against the French settlement and fort at Niagara or against Fort Beausejour in Nova Scotia, where the French used the vague wording in the Treaty of Utrecht to hang on to a vestige of their old colony of Acadia.

As the New York Assembly pointed out in 1754 the presence of the French on the Allegheny River (and by extension, at Fort DuQuesne) posed no threat to New York (or any other British North American colony).

It was solely the interests of the Virginia establishment and the Ohio Company that dictated that the primary action in the war should be an advance on Fort Duquesne, to remove the French from the Ohio Forks, where they blocked access to the land granted to the Ohio Company by the British Crown; the advance being made by way of Nemacolin’s Path, with a usable road constructed by the army as a valuable by-product.

It is the thesis of this site that Lord Albemarle used his influence with the Duke of Cumberland to ensure that the campaign in America was structured to realise the twin aims of the Ohio Company; removal of the French from the Ohio Forks and the building of a road along Nemacolin’s Path to the Ohio county.

The Duke of Cumberland’s plan for the 1755 North American campaign against the French:

The Duke of Cumberland directed that the primary military force in North America would comprise two regiments of British infantry sent from Britain to Virginia. This would be the first time for British regular army units to be used in North America.

Further military units would be recruited in the American colonies.

The British troops would march through Virginia to Will’s Creek, in the north-west corner of Virginia. From there they would advance in a westerly direction over the 80 miles to the Ohio River and capture Fort Duquesne. The route taken would follow Nemacolin’s Path and the troops would build a usable road along the route.

Once the French were driven from Fort Duquesne, the British troops would turn north and move up the Allegheny River against Fort Niagara.

A separate force, comprising colonial troops, would attack the French garrison at Fort Beausejour in Nova Scotia.

Objections to the Duke of Cumberland’s plan for the North American expedition:

The principal objection to the Duke of Cumberland’s plan for military action in North America in 1755 must be that the expedition was unnecessary and lead directly to a world war between Britain and France.

The French advance along the route of the Allegheny-Ohio River system and the building of Fort Duquesne posed little threat to the British North American colonies, the nearest border being 80 miles from the French, or ten days trekking through the forest. It mainly posed a threat to the profits of the Ohio Company.

Then, if a British attack was to be made on Fort Duquesne, the most appropriate approach was via Pennsylvania, not Virginia. There was a road through Pennsylvania to the west. There was no road through Virginia. The Pennsylvania farming economy could provide waggons and supplies. Virginia, with a slave-based tobacco economy, could provide neither transport nor supplies.

Recruits were required for the locally raised units and the two British regiments. There were few such recruits in Virginia and most were raised in Pennsylvania and Maryland.

If there had to be war with the French, the more appropriate strategy would have been to make the first attack on Fort Niagara.

With Fort Niagara taken, the French would be forced to withdraw from Fort Duquesne, as their communications via the Allegheny River would be cut.

The reverse did not apply. Once Fort Duquesne was taken, Fort Niagara would still have to be attacked.

However, simple French withdrawal from Fort Duquesne was not enough for the Viriginia interest. This required that the army build the road of some 80 miles along Nemacolin’s Path, to enable the Ohio Company to realise the value of its speculative land grant at the Ohio Forks.

The Earl of Halifax, probably the British minister with the greatest understanding of American affairs, was aware that the capture of Fort Niagara would compel the French to withdraw from Fort Duquesne. He told his fellow ministers as much. The same understanding was widely held in British America.

The documentation originating from the Duke of Cumberland and Robert Napier, his military secretary, in 1754, during the planning of Braddock’s expedition, shows a detailed grasp of military affairs in North America.

It is the thesis of this site that the Duke of Cumberland understood fully that the form of the expedition made little sense and served only special interests.

Cumberland probably had little or no concern with the interests of the Ohio Company itself. He did have concern with the interests of his close friend and confederate Lord Albemarle and his family.

In addition, the pervasive influence of the Ohio Company through the London businessman Hanbury and others will have eased the setting up of Braddock’s expedition in the form that it took.

It is interesting that once it became clear that the Duke of Cumberland’s plan for the conduct of the expedition was to be adopted, the Prime Minister, the Duke of Newcastle, went out of his way to state that the scheme was the Duke’s and not the Government’s.

As an aside it has to be pointed out that the Duke of Cumberland stated that the attack on Fort DuQuesne needed to be the first move because it could be made at a time of the year when the other objectives, Fort Niagara and Fort Beausejour, were still snow bound.

The only ‘picture’ of Edward Braddock. This image shows Braddock in the

uniform of an American general officer of the revolutionary period, some 20 years after his death. There is no reason to believe that it is a likeness

The arrangements for Braddock’s expedition:

As the Duke of Cumberland’s intention was to ensure that the primary attack on the French was on Fort Duquesne, an unnecessary exercise, conducted through the least appropriate colony, Virginia, along Nemacolin’s Path, with a time consuming and militarily pointless road constructed by the troops on the way, he needed a compliant and not very intelligent commander, with insufficient military experience to recognise that he was a dupe.

Edward Braddock exactly fitted these requirements. Until his appointment as colonel of the 14th Foot in 1753, Braddock spent his military career in the Coldstream Guards as a regimental subordinate to Lord Albemarle and the Duke of Cumberland.

Braddock possessed little field experience, his one foray being in 1745 to assess the defences of Ostend, but was courageous and doggedly determined.

Other personnel for the expedition were selected for their likely loyalty to Lord Albemarle: the deputy quartermaster-general, Sir John Saint Clair, was serving as an intelligence officer for Lord Albemarle in Flanders when appointed. Braddock’s aide de camp was another Coldstream officer, Robert Orme. The commodore appointed to command the Royal Naval squadron supporting the expedition was Lord Albemarle’s second son, Captain Augustus Keppel.

The orders drafted for Braddock and Keppel left them no option but to conduct the expedition in compliance with the requirement for a march through Virginia along Nemacolin’s Path and the capture of Fort Duquesne as the first aim.

Keppel’s orders directed him to land Braddock’s army in Virginia, taking it up the Potomac as far as possible in the direction of Will’s Creek.

At the time of the final preparations for the expedition, Edward Braddock was based in Gibraltar, where he was colonel of the 14th Foot. Braddock received a summons to return urgently to London, while cruising the Mediterranean in a Royal Navy ship.

Braddock landed at Marseilles and travelled through France to the Channel. On the way, Braddock stopped in Paris and spent two days with Lord Albemarle, who was serving as the British Ambassador.

Lord Albemarle specifically referred to Braddock’s two day stop-over in Paris in his official correspondence with the Prime Minister, the Duke of Newcastle.

A British infantryman of the 1750s: Death of General Edward Braddock on the Monongahela River on 9th July 1755 in the French and Indian War

Braddock was required in London as soon as possible, to be given his instructions and sail for America. There must have been an urgent need for him to spend these two days with Lord Albemarle, which is perhaps explained by Lord Albemarle’s intimate involvement in the planning and outcome of Braddock’s assignment.

Braddock needed to understand that the paramount aim of the expedition was to capture Fort Duquesne at the Ohio Forks and build the road along Nemacolin’s Path, and that the successful completion of these two tasks was essential to the interests of his recent colonel and influential member of the British court and establishment, his host in Paris, Lord Albemarle.

It is possible that Lord Albemarle offered Braddock a share in any financial gain that might follow from the re-taking of the Ohio Forks and the building of the road. However, this seems unlikely in view of Braddock’s later expressions of outrage on discovering the inadequacy of Virginia as the base for his army’s operations.

Braddock was and remained a dupe.

The planning for the Braddock expedition:

The Duke of Cumberland’s reputation in the Army and in British society rested on his successful defeat of the Jacobites under Prince Charles Edward Stuart at the Battle of Culloden on 16th April 1746. He achieved this success through his dogged determination, his ability to inspire his soldiers and his position as a royal duke, which gave him the co-operation of the disparate departments of the British military machine. Otherwise the Duke of Cumberland was a military incompetent.

The military planning abilities of Lord Albemarle and the Duke of Cumberland were insufficient to give the North American expedition a reasonable chance of succeeding.

The most glaring failure was to appoint a commander capable of conducting the expedition successfully. The characteristics that made Braddock an appropriate candidate, in the eyes of Albemarle and Cumberland, were characteristics that disqualified him from such a difficult command: lack of intelligence, lack of field experience, obstinacy, lack of diplomatic skills and lack of administrative experience, or even a capacity for hard work and application. Probably the only relevant qualities Edward Braddock possessed were bulldog bravery, obstinacy and a certain pugilistic charm.

The senior ranks of the expedition were riven with the prejudice of the day, an anti-Scots sentiment caused by the Jacobite rebellions. This was particularly pernicious as, in the main, the officers of the expedition with practical military experience were Scots: Sir Peter Halkett, Sir John Saint Clair and several of the officers of the Virginian companies, some of whom were probably fugitives from the Jacobite rebellion of 1745.

The campaign’s time-table was unreasonable for an almost completely inexperienced military force. No allowance was made for training and acclimatisation to the novel and frightening experience of operating in a vast expanse of virgin forest, under threat from Indians who, for the inexperienced troops, took on the characteristics of terrifying bogeymen.

Albemarle and Cumberland failed to anticipate the lack of adequate communications or transport resources in Virginia.

Orders were issued for recruitment of troops for which there was an inadequate reservoir of unemployed males.

Above all, Albemarle and Cumberland failed to take account of the general lack of resources in Virginia to support a substantial concentration of troops.

British military encampment: picture by Thomas Sandby: Death of General Edward Braddock on the Monongahela River on 9th July 1755 in the French and Indian War

Conclusion:

The Duke of Cumberland had a strong urge to make war against France and was looking for the appropriate place and justification to launch such a war.

The French operations on the Allegheny and Ohio Rivers and the actions of Robert Dinwiddie leading to the incident at Fort Necessity in 1754 provided the excuse for hostile operations.

It is this site’s contention that against this background, the Duke of Cumberland planned the Braddock Expedition to capture Fort Duquesne, with an approach march through Virginia, along Nemacolin’s Path, building a usable road, specifically to advance the financial interests of his friend, Lord Albemarle, and at Lord Albemarle’s request.

Mortally wounded, General Edward Braddock is carried back from the Monongahela to Great Meadows Camp where he died on 12th July 1755: picture by Alonzo Chappel

The consequences of Braddock’s catastrophic defeat were appalling; first, in unleashing a wave of Indian terror against the colonists living in the western and central parts of Virginia, Maine, Pennsylvania and New York; then, in the outbreak of the French and Indian War in North America and the Seven Years War elsewhere in the world and; finally, the severe decline in the prestige of British government in the North American Colonies, leading to the American War of Independence in 1775.

The previous section on Braddock’s defeat on the Monongahela in 1755 is Part 10: Braddock’s final battle on 9th June 1755.

The next battle in the British Battles series is the Battle of Ticonderoga

To the French and Indian War index