The account of General Braddock’s expedition to Fort Duquesne in 1755:

Part 5: Braddock’s regiments, Halkett’s 44th and Dunbar’s 48th, and his departure for Virginia.

Grenadier of Colonel Sir Peter Halkett’s 44th Regiment: Death of General Edward Braddock on the Monongahela River on 9th July 1755 in the French and Indian War: picture by David Morier

The previous section on Braddock’s defeat on the Monongahela in 1755 is Part 4: The appointment of Edward Braddock as commander-in-chief in America in November 1754.

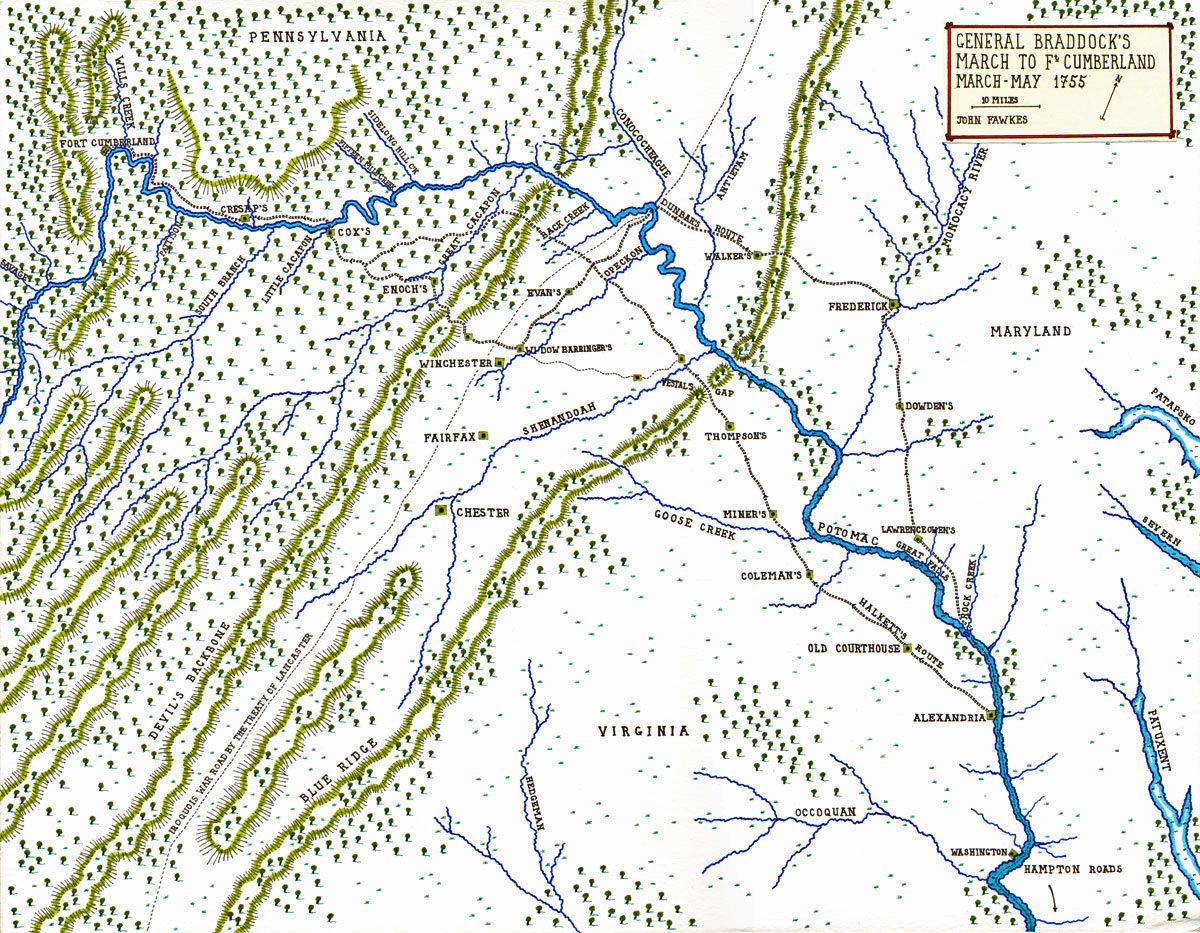

The next section on Braddock’s defeat on the Monongahela in 1755 is Part 6: Braddock’s march to Will’s Creek, via Alexandria, Frederick and Winchester in Virginia and Maryland in 1755.

To the French and Indian War index

Grenadier of Colonel Dunbar’s 48th Regiment: Death of General Edward Braddock on the Monongahela River on 9th July 1755 in the French and Indian War: picture by David Morier

The British Army of 1754:

The British Army remained much the same in structure and tactics throughout the first half of the 18th Century. In 1754 there were 4 troops of Horse Guards and 2 troops of Horse Grenadier Guards providing the immediate bodyguard for the Sovereign. The rest of the cavalry comprised 8 regiments of horse (7 of which were entitled ‘Dragoon Guards’) and 14 regiments of dragoons. The infantry in 1754 comprised the 3 regiments of Foot Guards, 50 regiments of foot that were distributed across Great Britain and Ireland and in garrison in Gibraltar and Minorca and a number of Independent Companies that provided garrisons for particular towns and fortifications. The only royal troops in the American colonies were 4 Independent Companies in New York and 1 in South Carolina. The Royal Artillery was in 1751 incorporated into the army. The sole regular artillery unit in North America was an artillery company in Nova Scotia.

A ‘Marching Regiment’ (regiment of foot) at wartime establishment comprised 10 companies. Each company was officered by a captain, a lieutenant and an ensign and comprised 3 sergeants, 3 corporals, 3 drummers and the balance of 70 to 100 private soldiers, at least in theory. The field officers in a regiment were the colonel, the lieutenant colonel and the major. A regiment possessed a small staff of a chaplain, a surgeon, a quartermaster and an adjutant. The adjutant was usually one of the company officers. The financial affairs were administered by a civilian agent. A soldier was provided with his uniform and weapons, which comprised a musket, bayonet, small sword known as a ‘hanger’ and for battle 24 cartridges carried in a large leather pouch slung from a leather cross belt. The uniform comprised a coat, which was issued anew annually at least in theory with the old coat cut down to form a waist coat, britches, stockings, shoes and thigh-length gaiters, white for parades and black for field use.

General Braddock’s March to Fort Cumberland through the Northern Neck of Virginia and through Maryland – March – May 1755 – Map by John Fawkes: Death of General Edward Braddock on the Monongahela River on 9th July 1755 in the French and Indian War

A belt and cross belt were worn. For headgear the battalion companies wore a tricorne hat bound with lace and the grenadiers wore a tall highly decorated mitre cap.

There were few barracks. Most regiments were quartered in towns, their soldiers billeted on houses selling liquor, an arrangement authorised by the annual Mutiny Acts, with a company or more to a town depending on its size. In peacetime many officers were absent from their duty, pursuing other interests such as running country estates, acting as Members of Parliament or just enjoying the social round.

Officers’ commissions up to the rank of colonel or commander of a regiment were bought and sold and were much sought after among the upper classes. The value of a commission depended on the rank and the social status of the regiment. In wartime promotion was made by merit in addition to purchase. Embezzlement of soldiers pay and the grants for equipment by regimental officers was an accepted feature of the system as in civilian public appointments.

Promotion above the rank of colonel was to the various ranks of general. A general usually retained his appointment as colonel in command of a regiment. As a general officer was advanced in rank and status he might well be permitted to purchase the colonelcy of a more prestigious regiment.

Officers and soldiers were required to feed themselves from their pay, purchasing and cooking food in groups, the origins of the ‘mess’. This system was based on the assumption that in any area there was food and drink available for purchase. This assumption was not valid for North America, as the British regiments posted there during the French and Indian War were to find out.

Recruitment of private soldiers was conducted by recruiting parties attending at fairs and other public gatherings or in drinking houses. Enlistment was effectively for life or until a soldier was too decrepit or old to be capable of duty, or the regiment was ‘reduced’ as no longer needed, as at the end of a war.

Desertion was rife. It was relatively easy to desert and the chances of being caught were slim, unless the deserter remained in the regiment’s area. Discipline was haphazard and punishments severe. Deserters from the Foot Guards were regularly given several hundred lashes in the presence of their colleagues.

Service overseas was unpopular. Regiments posted to the colonies had to be rushed to ports and onto the ships, before the soldiers realised what was happening to them. Otherwise the regiment would be decimated by desertion.

Drunkenness was rife among soldiers and proved a major problem for Braddock, until he took his army west and away from the sources of alcohol.

There was no established system for training either officers or men. Such training as there was was implemented by regimental officers and depended on the ability and commitment of those officers. In practice regiments went untrained until war broke out when they learnt by hard experience.

St James’s Park: picture by Canaletto, showing Foot Guards parading outside the Horse Guards: Death of General Edward Braddock on the Monongahela River on 9th July 1755 in the French and Indian War

The total pay bill to central government for a regiment of 800 officers and soldiers was approximately £35 a day or £1,000 a month.

The Duke of Cumberland, the younger son of King George II, possessed a profound commitment to the British Army. He used his post as Captain General during the period between the Treaty of Aix la Chapelle in 1748 and the outbreak of the Seven Years War in 1756 to impose much needed reforms on the army, in the teeth of strenuous opposition much of it coming from within the army itself.

Cumberland was much assisted by his high standing in the country and the armed forces following his victory over Prince Charles Edward Stuart at the Battle of Culloden in 1746, which brought the dangerous Jacobite Rebellion to an end.

The King and Cumberland would have liked to abolish the system of sale and purchase of officers’ commissions, but this was politically unachievable.

The 44th Foot and 48th Foot:

The two regiments of foot designated for General Braddock’s force were Colonel Sir Peter Halkett’s 44th Regiment and Colonel Thomas Dunbar’s 48th Regiment. Both regiments had been raised in 1741 with the impending war against Spain in the West Indies and the prospect of war with France in the Netherlands. The 44th, then denominated Colonel Lee’s Regiment, with Halkett as the lieutenant colonel formed part of the garrison in Scotland when Prince Charles Edward Stuart landed there in 1745 and began the Jacobite Rebellion.

At the Battle of Prestonpans on 2nd October 1745 Lee’s Regiment was overwhelmed by the Highland charge with the rest of the Government foot. Halkett with fifteen of his soldiers was persuaded to surrender to the Jacobites at the end of the battle. Lee’s regiment took no further part in the ’45. The stigma of cowardice, incompetence and defeat still hung heavily over the regiment ten years later. When reporting the result of Braddock’s campaign in late 1755 the Gentleman’s Magazine commented on the regiment’s performance at Prestonpans.

The experience of the 48th was very different. Raised by Colonel Cholmondeley, the 48th fought at the Battle of Falkirk on 28th January 1746 and was one of the three regiments of government foot that stood their ground when the Highlanders charged, while the other regiments fled. With the new denomination of ‘Ligonier’s Regiment’ the 48th fought at the Battle of Culloden on 27th April 1746, where the Duke of Cumberland destroyed the Highland Army and ended the ’45 rebellion. While the 44th was in disgrace the reputation of the 48th could not have been higher. Cumberland ensured that the colonelcy of the 48th was bestowed on his favoured staff officer Colonel Henry Seymour Conway. The 48th joined Cumberland’s army in Flanders and fought with distinction at the Battle of Lauffeldt.

The Treaty of Aix la Chapelle brought fundamental changes to the British army. The Government required a reduction of around 60% in the size of the army and the ‘breaking’ (disbandment) of the newly raised regiments. Cumberland managed to save the 48th but only by transferring the regiment to the Irish establishment, effectively putting it outside the control of the British Government. There was however a price. Regiments of foot, on being moved to Ireland, changed from the British establishment of between 750 and 1,000 men to an Irish establishment of around 350 men. Many of the officers went on half pay, a form of retirement, and few of the remaining officers continued at their duty. The 48th became a shadow of its previous wartime self.

Between 1748 and 1755 Cumberland brought about significant improvements in the organisation, tactics and training of the regiments of foot under his immediate jurisdiction in Britain. These changes did not extend to the regiments on the Irish establishment, under the jurisdiction of the commander-in-chief in Ireland, a jurisdiction jealously guarded against interference from Cumberland in England.

Cumberland’s initial proposal, that the regiments for North America be drawn from the British establishment was vetoed by the King who feared that they would be needed in case of a European War with France. The regiments designated for Braddock’s expedition were to come from the Irish garrison and were the two junior regiments in Ireland. The 44th had probably never been a competent regiment. Since 1748 the 48th had deteriorated until both regiments were equally inadequate.

Sir Peter Halkett’s 44th Regiment of Foot: Death of General Edward Braddock on the Monongahela River on 9th July 1755 in the French and Indian War

Comments on the state of the 44th and 48th at the end of 1755 by British officers in America expressed the view that these regiments were incapable of useful service.

A proposal was made to Cumberland in September 1754 to raise regiments of Scottish Highlanders for deployment in Virginia, but it would require several months to recruit them. Cumberland rejected the idea as taking too long.

The two regiments selected, the 44th and the 48th, were to be brought to a war establishment in part with drafts from other regiments in Ireland and England and in part by recruiting in America on arrival.

The drafts came from these regiments: 100 men from Bury’s 20th at Bristol, 100 from Buckland’s Regiment at Salisbury and from regiments in Ireland; 78 sergeants, corporals, drummers and soldiers from Bragg’s 28th, the same from Pole’s 10th, Anstruther’s 26th and the 2nd Battalion of the Royal Regiment (1st). The ‘drafting’ regiments inevitably sent their least desirable soldiers. Braddock and his staff would in due course discover the problems of recruiting in the American colonies. Cumberland’s instincts in most of his dealings with the Army were sound. In this respect he made a bad miscalculation.

Braddock was being dispatched into almost unknown territory with a force that would comprise around 50% newly enlisted recruits with his longer serving soldiers coming from probably the two least competent regiments in the British Army brought up to something approaching war strength with the throw-outs from other regiments.

Braddock was condemned to commanding a force whose discipline was fragile at best and which, in the moment of crisis, would collapse completely.

Sir Peter Halkett colonel of the 44th Foot in General Braddock’s army at the Battle of the Monongahela 1755: Death of General Edward Braddock on the Monongahela River on 9th July 1755 in the French and Indian War

Sir Peter Halkett, colonel of the 44th Foot:

Sir Peter Halkett was a prominent Scottish baronet with an estate in Fife in Scotland. Halkett was the Member of Parliament for Dumfermline from 1733 and the Provost of Dumfermline from 1751. It is unlikely that Halkett spent much time with his regiment in Ireland. Absence from duty by officers was one of the abuses that Cumberland spent much time combating but the regiments in Ireland were outside his remit.

It is clear that Cumberland and Braddock had little time for Halkett. This was unfortunate as Halkett through seniority should have been the second in command of the force. In fact Braddock appointed Dunbar as his second in command. In the ’45 Jacobite Rebellion the King and Cumberland suspected that the catastrophic collapse of the Royal Army at Prestonpans was due to the treachery of officers with Jacobite sympathies in the army’s ranks. Halkett, as the commander of Lee’s 44th Regiment at the battle in the absence of Colonel Lee was likely to have fallen under that suspicion. After his capture by the Jacobites Halkett was released with other government officers against an undertaking that they would not serve further during the course of the rebellion. Cumberland ordered these officers to return to their duty. Halkett refused to do so, rejecting Cumberland’s argument that he was not bound by an oath given to a rebel against the Crown. Cumberland dismissed Halkett from the Army. Halkett appealed to the King and was re-instated.

Suspicion as to Halkett’s loyalty lingered on and without a doubt prejudiced Braddock and his English officers against him during the operations in America in 1755.

The Highland attack at the Battle of Prestonpans 2nd October 1745 when the 44th Regiment was overwhelmed

Colonel Thomas Dunbar, colonel of the 48th Foot:

Thomas Dunbar was commissioned into the 18th Royal Irish Regiment of Foot in 1722. He served in that regiment, rising to the rank of lieutenant-colonel, until 1752 when he became colonel of the 48th Regiment. Dunbar does not appear to have seen action during his career before 1755.

During his advance to the Ohio Forks Braddock put Dunbar in command of the second force that was left to bring up the supplies while the main force marched on to Fort Duquesne.

After Braddock’s defeat and death, when the command of the army fell on Dunbar he took his force back to Philadelphia into ‘winter quarters’, although the date was mid-July, leaving western Virginia and Pennsylvania to be ravaged by the Indians unleashed by the French following their victory.

Dunbar wrote to Cumberland’s adjutant Colonel Robert Napier by letter dated 24th July 1755, written after his withdrawal to Philadelphia. In this letter Dunbar stated: ‘This climate by no means agrees with my time of life and bad constitution. I was willing to try and hoped I should be able to go through all that came in my way, but find otherwise, therefore beg your interest to gett me leave to go home; was I as able as I am willing I assure you I would gladly stay.’

Sir John Saint Clair, Deputy Quartermaster General:

Sir John Saint Clair, lieutenant-colonel and Deputy Quartermaster General to General Braddock’s army, was born in Kinnaird in Fifeshire, Scotland

Little is known of Sir John’s background. He is described in the Army Lists as ‘Sir John’, so that suggestions that his baronetcy was spurious (made by Pargellis) appear to be unfounded. His grandfather, Sir James Saint Clair, was the first baronet. Saint Clair was commissioned as an ensign into Colonel Paget’s 22nd Regiment of Foot in 1735.

In 1754 Saint Clair was a captain in the 22nd when on 15th October 1754 he was appointed the Deputy Quartermaster General in America with the acting rank of Lieutenant-Colonel.

The appointment as ‘Deputy’ reflects that he was not a ‘General’, not that he was deputy to a Quartermaster General. While there is no document that outlines Sir John’s duties, it is apparent that he took on a wide range of obligations, from recruiting for Braddock’s force, organising encampments, inspecting recruits already raised and conducting reconnaissance through Virginia, all in anticipation of Braddock’s arrival. Once the march to Fort Duquesne began Sir John supervised the building of the road by the engineers and their working parties.

In his circular addressed to the farmers of Pennsylvania in June 1755 Benjamin Franklin described Sir John as being a ‘Hussar’. This would appear to have been part threat, part joke and a reference to Sir John having served with the Austrian Army. Whether Sir John did so serve is unknown.

Sir John Saint Clair was one of the Scottish officers held in contempt by Braddock. Sir John’s regiment was an English regiment and took no part in suppressing the ’45 Rebellion. There would appear to have been no basis for questioning his loyalty, and that Braddock’s expedition reached the area of the Ohio Forks at all was in substantial measure due to the commitment and energy of Sir John Saint Clair.

The Naval Arrangements:

The orders issued to Commodore Keppel in early December 1754 by the Lords of the Admiralty informed Keppel that he was given a force comprising two Ships of the Line; HMS Centurion, his Flagship, and HMS Norwich, which was to convey Braddock and his staff; two Frigates, HMS Seahorse and HMS Nightingale; and thirteen transports to convey the two regiments of foot, the contingent of Royal Artillery with their guns, the equipment and weapons for the two regiments to be raised in America and the staff and equipment of the field hospital. The troops were to be conveyed under the escort of the two frigates from Cork to Virginia, while the two ships of the line sailed from Spithead carrying Keppel and Braddock.

The Admiralty, at least, foresaw the difficulty with local supply for the troops in America. Keppel’s orders directed him to provide Braddock’s troops with a thousand barrels of beef, ten tons of butter and any other stores left over in the transports after the voyage. Without these supplies Braddock’s army would have starved.

Keppel was instructed to provide the military force with a party of seamen. Two officers were attached to his flotilla to land and accompany the army; Lieutenants Charles Spendlow and William Shackerly. Spendlow was the officer who accompanied Braddock and was killed in the battle, while Shackerly was employed on duties in the Northern Colonies. Spendlow was instructed to assist the troops in making floats to get them over water and to prepare maps of the country. The seamen and their officers were invaluable to Braddock. They supervised and conducted the many water crossings. Their experience and use of tackles enabled Braddock’s waggons to be hauled up and lowered down the mountain sides. They were ‘can do’ men while many of the soldiers were quite the reverse; drunken, ill-disciplined and frightened.

A British frigate in the Seven Years War: picture by Dominic Serres

HMS Centurion was equipped with the ironwork, cordage and sails to build a 60 ton ‘armed vessel’ to operate on Lake Ontario. Spendlow was to command this ship, presumably after building it. Clearly Spendlow was considered a resourceful officer.

The transport ships allocated for the force were: Anna, Terrible, Osgood, Concord, Industry, Fishburn, Halifax, Fame, London, Prince Frederick, Isabel and Mary and Molly. In addition there were three Ordnance store ships, Whiting, Newall and Nelly. Of these ships Osgood and possibly Fishburn were owned by John Hanbury, agent and member of the Ohio Company and lender of the £10,000 reserve of specie carried by the expedition.

The transport ships and Ordnance store ships assembled at Cork where they took on board the stores and the men of the 44th and 48th Regiments with the additional drafts and left for Virginia on 14th January 1755.

Keppel and Braddock, accompanied by his secretary William Shirley (son of Governor Shirley of Massachusetts) and his aide de camp Captain Robert Orme sailed from England on 21st December 1754 in Centurion, Norwich and Syren. They arrived at Hampton Roads in Virginia on 20th February 1755.

Norwich and Syren immediately put out to sea again to meet the transports, in the light of a report that two French warships were in the vicinity.

The fleet of transports became separated during the long voyage across the Atlantic. The first transports to arrive at Hampton were Hanley’s ships Osgood and Fishburn, carrying a contingent of troops, on 2nd March 1755. The last transport carrying troops, Severn, arrived at Hampton in mid-March 1755.

The previous section on Braddock’s defeat on the Monongahela in 1755 is Part 4: The appointment of Edward Braddock as commander-in-chief in America in November 1754.

The next section on Braddock’s defeat on the Monongahela in 1755 is Part 6: Braddock’s march to Will’s Creek, via Alexandria, Frederick and Winchester in Virginia and Maryland in 1755.

To the French and Indian War index