The account of General Braddock’s expedition to Fort Duquesne in 1755:

Part 4: The appointment of Edward Braddock as commander-in-chief in America

Foot Guards’ march to Finchley in 1745 caricatured in the picture by William Hogarth. On seeing this picture King George II is reported as asking “Is the fellow laughing at my Guards?” Death of General Edward Braddock on the Monongahela River on 9th July 1755 in the French and Indian War

The previous section on Braddock’s defeat on the Monongahela in 1755 is Part 3: The Planning of General Braddock’s expedition.

The next section on Braddock’s defeat on the Monongahela in 1755 is Part 5: Braddock’s regiments, Halkett’s 44th and Dunbar’s 48th, and his departure for Virginia.

To the French and Indian War index

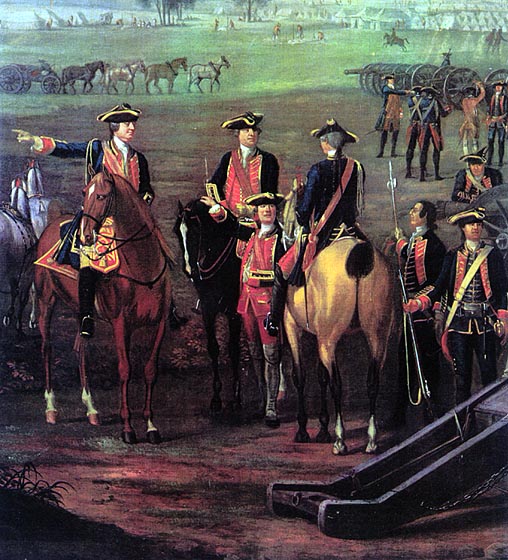

The only ‘picture’ of Edward Braddock. This image (right) shows Braddock in the

uniform of an American general officer of the revolutionary period, some 20 years after his death. There is no reason to believe that it is a likeness

Edward Braddock:

Edward Braddock remains a shadowy figure. He sprang to prominence as commander-in-chief in America from being colonel of the 14th Foot in garrison in Gibraltar, after a long but unremarkable career as a regimental officer of the Foot Guards. Within eight months of his appointment Braddock would become notorious following the disaster of his defeat and his death and burial in a remote corner of an American forest. There is no portrait of him that is known.

It is likely that the factor that brought the appointment of commander-in-chief in America upon Edward Braddock was that he had been an officer in the Coldstream Guards.

Braddock spent his career as a Guards officer in London and the Home Counties. In peacetime there was no formal battalion structure in the Foot Guards, the company being the significant sub unit. It was a commonplace that the Foot Guards were run by their sergeants and corporals, leaving the officers to their gentlemanly activities. Braddock’s one foray into the continental war was for a few months in 1747, commanding a battalion in the abortive attempt to relieve the Dutch town of Bergen-op-Zoom, besieged by the French.

Braddock may have taken part in the episode of hectic marching through England in the attempt to catch the Jacobite army in late 1745. That appears to have been the limit of his military experience.

Pargellis reproduces in his ‘Military Affairs in North American 1748-1765′ a document he entitles ‘Anonymous Letter on Braddock’s Campaign‘. The letter is dated 25th July 1755 from Wills’s Creek. Pargellis attritubutes the letter as possibly written by Captain Gabriel Christie assistant to Deputy Adjutant General Sir John Saint Clair. The letter states of Braddock ‘In the time of the Action, the General behaved with a great deal of personal courage, which every body must allow-but that’s all that can be said- He was a man of sense and good natur’d too tho’ warm and a little uncouth in manner- and peevish- with all very indolent and seem’d glad for any body to take bussiness off his hands, which may be one reason why he was so grossly imposed upon, by his favourite- who realy dirrected every thing and may justly be said to’ve commanded the expedition and the army’. This is a clear reference to Braddock’s ADC Captain Robert Orme who became the main target of blame after the disastrous end of the expedition.

Edward Braddock in Thackeray’s “the Virginians”

Several pages in Thackeray’s ‘The Virginians’, published in 1857, are devoted to Braddock’s arrival in Virginia in 1755. Thackeray is said to have talked to Virginians one generation removed from the events of the time during his visit to America in 1851. Thackeray portrayed Braddock as enjoying a sympathetic relationship with Benjamin Franklin, referred to by the English officers as ‘the Postmaster’.

Thackeray wrote: “He [Braddock] does his best,” says Mr Franklin, looking innocently at the stout chief, the exemplar of English elegance, who sat swagging from one side to the other of the carriage, his face as scarlet as his coat- swearing at every word; ignorant on every point off parade, except the merits of a bottle and the looks of a woman; not of high birth, yet absurdly proud of his no-ancestry; brave as a bull-dog; savage, lustful, prodigal, generous; gentle in soft moods; easy of love and laughter; dull of wit; utterly unread; believing his country the first in the world, and he as good a gentleman as any in it.”

An illustration from the original edition of Thackeray’s

‘The Virginians’ showing Braddock and George Washington

Thackeray has Braddock saying to Benjamin Franklin of the Duke of Cumberland: “He is the soldier’s best friend, and has been the un-compromising enemy of all beggarly red-shanked Scotch rebels and intriguing Romish Jesuits who would take our liberty from us, and our religion, by George. His Royal Highness, my gracious master, is not a scholar neither, but he is one of the finest gentlemen in the world.”

Braddock here uses the English expletive ‘By George’, which dated from the mid-18th Century and was devised and used by those firmly loyal to the King Georges of the House of Hanover and anti-Jacobite.

Braddock’s appointment as Commander-in-Chief in America:

Edward Braddock, during his long service in the Coldstream Guards will have been well known to the Earl of Albemarle, who became the colonel of the regiment in 1744 having first joined it in 1717. Braddock was probably well known to the Duke of Cumberland. The Foot Guards were Cumberland’s principal tool in imposing a standard form of battle drill on the regiments of foot during Cumberland’s period of military reform between 1748 and 1754 and Braddock was one of only a handful of lieutenant colonels in the three Foot Guard regiments.

When Braddock commanded the battalion of the Coldstream in Holland in 1747 Albermarle’s eldest son, Lord Bury, was one of his company captains. It is likely that Braddock’s appointment to the command-in-chief in America was supported by Albemarle and Bury, if not actually proposed.

Captain Robert Orme, appointed as Braddock’s Principal ADC and in practice his chief of staff, was serving as a lieutenant substantive captain in the Coldstream in 1754. Orme’s recommendation will have come from Braddock and from Lord Bury. Orme received his commission in the Coldstream in 1745 and was probably little known to Albemarle, whose ambassadorship in Paris must have precluded active involvement in regimental affairs.

Captain Robert Orme: picture by Joshua Reynolds, painted after Orme’s return from America. The scene is clearly the American forest. Battle smoke can be seen in the background

It is unlikely that Cumberland and Albemarle will have been unaware of Braddock’s limitations. It may be that Braddock’s appeal was that he could be expected to do exactly what he was told and bulldoze his way through any difficulties.

Keppel appointed Commodore:

On 9th October 1754, the Lords of the Admiralty appointed Captain Augustus Keppel commodore in command of the vessels off the coast of America in support of Braddock. Keppel’s first task was to transport Braddock, his staff, the two regiments of foot, the artillery and Ordinance stores to America.

Commodore Augustus Keppel was Lord Albemarle’s second son. It was notorious that Cumberland’s influence over the Royal Navy was almost as great as his sway over the Army. Cumberland may well have directed Anson, the First Lord of the Admiralty, to appoint Keppel to the post.

The Virginia-Cumberland-Albemarle control over the impending expedition to the Ohio Forks was complete.

Braddock’s instructions:

Braddock’s instructions left him little room for strategic initiative. Keppel’s instructions from the Admiralty directed him to land Braddock and his force in Virginia, so there was no discretion there.

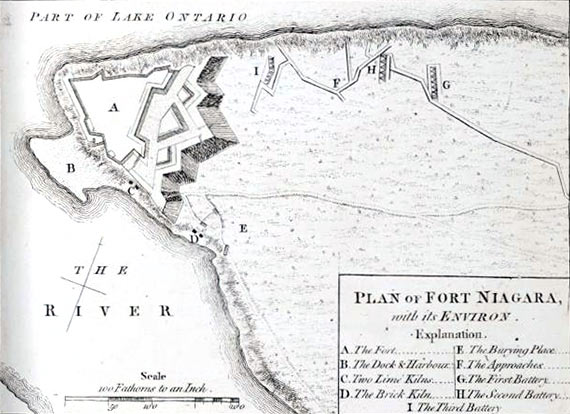

The memorandum on which Pargellis states that Braddock’s secret instructions were based makes it absolutely clear that Braddock’s first task was to take his two regiments to Will’s Creek, to march to Fort Duquesne at the Ohio Forks and to capture the fort. The memorandum is explicit as to the order of operations in North America: Fort Duquesne first, then Niagara, followed by Crown Point and finally Fort Beausejour in Nova Scotia.

The letter dated 25th November 1754 written to Braddock by Colonel Robert Napier as Cumberland’s Adjutant General is clearly based on the assumption that Braddock’s first task was to conduct the attack on Fort Duquesne from Will’s Creek.

Was the form of Braddock’s orders in the British interest?

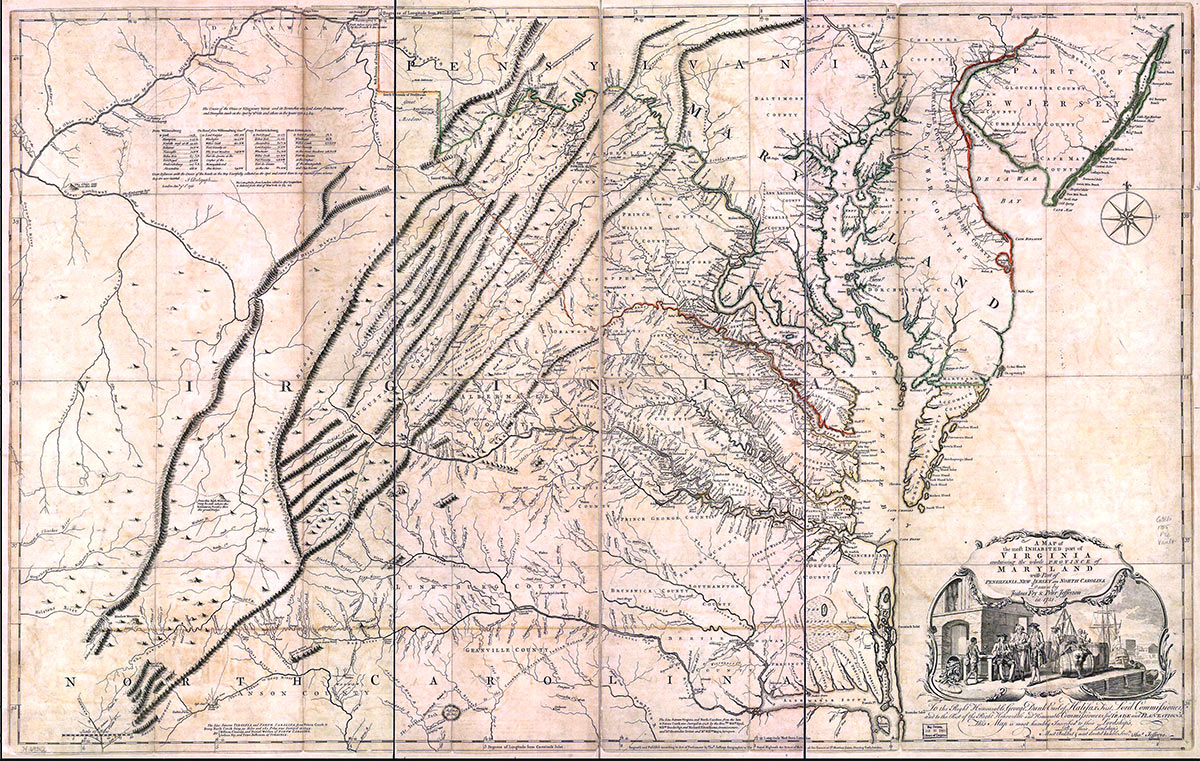

The military expedition to America appears to have been an Albemarle-Virginia affair guided by the interests of the Ohio Company. Did the form of the expedition and its planned aims coincide with the interests of the British American Colonies as a whole and of the British state? The answer has to be that it did not. The French presence at the Ohio Forks was small and precarious and concerned with maintaining the north-south river route from Canada to Louisiana. The Ohio Forks were over a hundred miles from any significant Virginian or Pennsylvanian population. The real French threats were in Nova Scotia, New Hampshire and New York. Lord Halifax, a minister with a greater understanding of North America than his colleagues, pointed out during the meetings in September 1754 that if Fort Niagara was taken the French would be forced to withdraw from the Ohio Forks, as their communications would be cut. George Washington made the same point in a letter written, but not sent, dated 14th May 1755. It is likely that this was the general understanding in America.

Dinwiddie, the Virginia establishment and the members of the Ohio Company stood to make significant gains from a successful British campaign through Virginia to the Ohio Forks; through the prestige of their involvement in a high profile military action, through the economic benefit of large scale military activity in Virginia, but above all through the building by Braddock’s army of a viable road along Nemacolin’s path to the area of the Ohio Company’s large land grant at the Ohio Forks. In the event, the consequence of the campaign was disaster for all; no usable road, the eventual demise of the Ohio Company, a long and expensive war and significant erosion of the standing of the British Crown in North America.

Virginia:

The authorities in London can have had little idea of the topography of Virginia. The assumption was clearly made that Virginia was much like a European state, with well established towns, reasonable communications by land and water, a substantial rural population able to supply the produce needed to sustain an army and an availability of draught animals and vehicles to transport such a force and its baggage. That was the European experience of making war and the pre-requisite on which conventional European military planning was based.

Virginia did not begin to comply with these assumptions. The area of the colony was large. The population by European standards was tiny and concentrated along the Atlantic seaboard. Travel was largely by sea along the coast. The limited road system on the eastern coast were almost entirely unbridged and relied upon fords or ferries.

The few established towns were small and situated in the southern coastal region.

The three towns that were of significance to Braddock’s plans were; Alexandria on the Potomac, which had only begun to be constructed in 1753, two years before Braddock’s arrival; Winchester in Western Virginia, only established as a town in the 1740s, and Frederick in Maryland established as a town in 1743.

Virginia did not have the resources of foodstuffs or transport for the needs of Braddock’s army, nor did it have the pool of unemployed men to fill the recruiting requirements of Braddock’s various units.

Once Braddock’s army moved west of Alexandria, it found that the Virginian roads were abysmal to non-existent. From Winchester to Will’s Creek the roads were simply paths that followed the courses of streams, frequently in the stream.

A particular complaint of the deputy adjutant general, Sir John Saint Clair, Braddock and others was that the Virginians were far from frank about the inadequacies of these features of their colony, so that it was only when Braddock and his officers were confronted with the lack of supplies or a near-impassable route that it was realised just how inappropriate Virginia was as the theatre of operations.

Braddock was at Alexandria and committed to an advance through Virginia, when he realised that Pennsylvania possessed many of the resources that Virginia did not have and that he so desperately needed.

In the end it was Pennsylvania, through the offices of Benjamin Franklin, that provided the supplies and transport that enabled the expedition to progress at all from Alexandria.

Not only did Dinwiddie and the Virginian establishment cause the war for their own ends they also misled the British Government and its officers on the appropriateness of their colony as the base and route for the expedition. In addition, when Braddock was compelled to turn to Benjamin Franklin and the Pennsylvanians to fill his unmet needs for supplies and transport wagons and had to route one of his regiments, the 48th, through Pennsylvania, he faced shrill complaint from the Virginian authorities.

One of the major misconceptions held by Cumberland and Napier was that the Potomac River was navigable as far as Wills’ Creek. Pargellis reproduces in his ‘Military Affairs in North American 1748-1765′ a document he entitles ‘Sketch for the Operations in North America Nov 16: 1754′. Pargellis describes this document as the ‘basis for Braddock’s secret instructions‘ discussed by Cumberland with Braddock and supported by a letter. This document states: ‘The Troops should therefore be carried up the Potomac River, as high as Will’s Creek…’

Colonel St Clair, the Deputy Quartermaster General, on his arrival in Virginia on 9th January 1755 was informed by Dinwiddie that the Potomac was not navigable above Alexandria, a fact that St Clair confirmed for himself on attempting to travel back from Fort Cumberland at Wills’ Creek by canoe with Governor Sharp.

It is not apparent who led Cumberland to believe that Braddock’s troops could be transported up the Potomac River from Alexandria to Wills’ Creek, but it was an important piece of misinformation adding a significant complication for Braddock, who had to send his troops by land and without the benefit of a road system.

While not expressly stated how long the Ohio Forks campaign was expected to take, it would seem that Braddock’s and Cumberland’s expectations were that Fort Duquesne would be captured from the French within perhaps two weeks of Braddock’s arrival in Virginia. In the event it took nearly four months for Braddock to bring his force within a few miles of the French fort, where it was heavily defeated.

The financing of Braddock’s operations:

King George II at the Battle of Dettingen in 1743: picture by David Morier

A major requirement in the preparation of Braddock’s expedition to Virginia was to put in place the necessary finance.

Contrary to the image portrayed by his critics, the British Prime Minister the Duke of Newcastle was an astute and experienced politician. In conducting public affairs Newcastle had to take into account two essential political considerations; first, the preservation of Hanover, an obsession with King George II on whose goodwill Newcastle depended and second, the limiting of government expenditure. In pursuit of each of these goals Newcastle had little interest in unnecessarily antagonising the French.

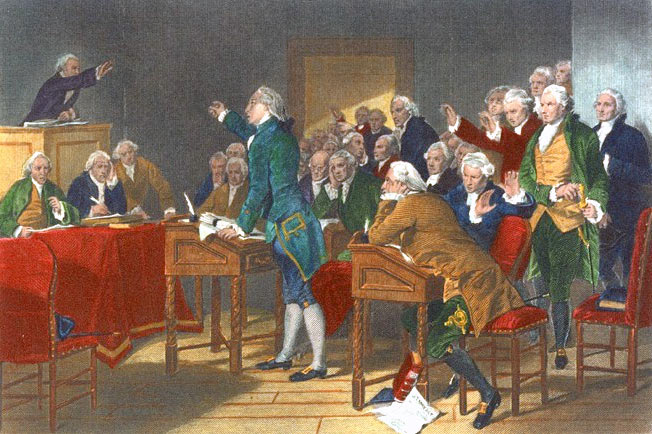

Developments in Virginia, culminating in the Fort Necessity capitulation in 1754, forced Newcastle’s hand. Public and Royal opinion required that military action be taken against the French, even if this threatened to cause a European war and incurred significant expenditure.

The first arrangement, devised in September 1754, was the best for the British Government as its financial exposure would be minimal: Governor Horatio Sharpe of Maryland would be made commander-in-chief in America and given the task of retaking the Ohio Forks using only provincial resources. Sharpe would probably have achieved this.

The King then gave his ‘permission’ for the Duke of Cumberland to be consulted. Cumberland’s initial proposal was for a viceroy to be appointed in America to act as the commander-in-chief and as the overall ruler of the British colonies. Cumberland had in mind his close associate the Earl of Albemarle for this post. Albemarle was serving as the British Ambassador in Paris and was already Governor of Virginia. The King rejected the idea of a viceroy.

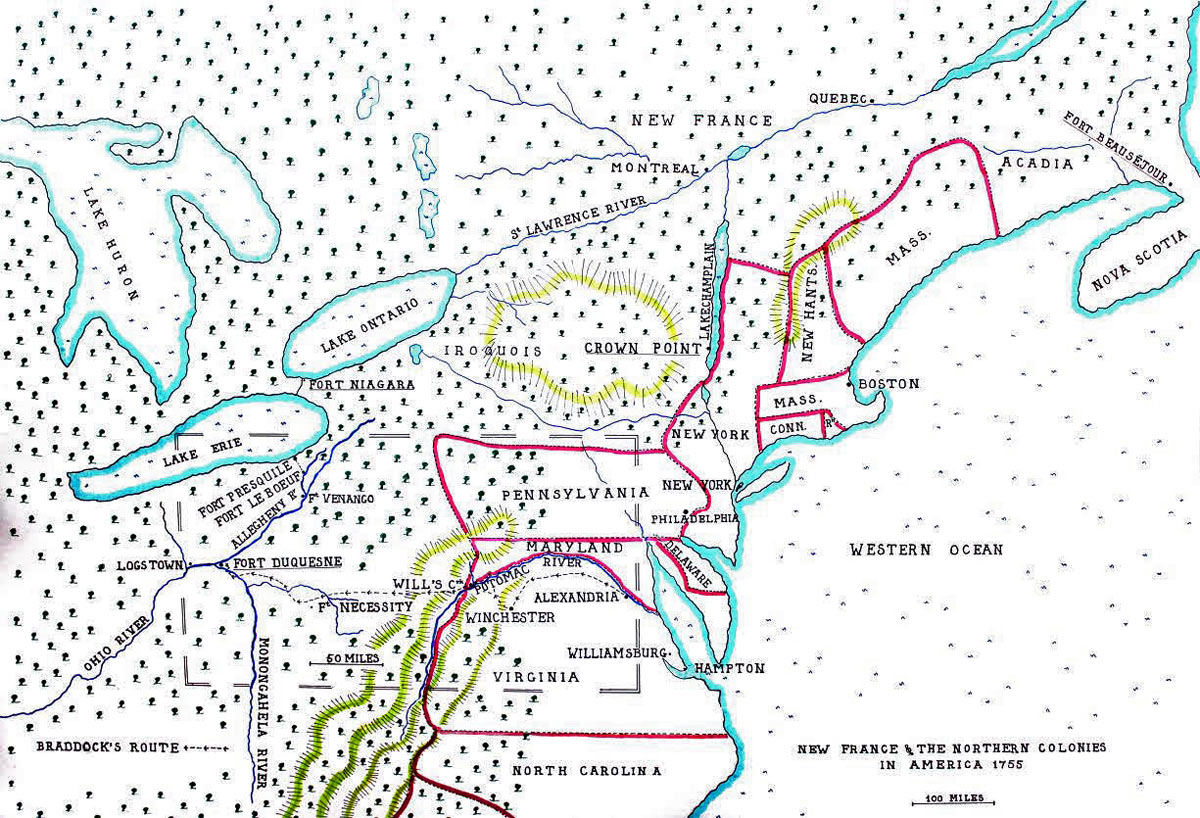

Map of the North American Colonies in 1755 showing the four intended targets for the British offensive operation: Fort Duquesne, Fort Niagara, Crown Point and Fort Beauséjour: map by John Fawkes

Cumberland’s replacement proposal was that a serving British officer be sent to America as commander-in-chief. He would take two royal regiments and, advancing through Virginia, attack the French at the Ohio Forks. The operation on the Ohio would be followed by aggressive action against the French at Fort Niagara, Crown Point in New York Colony and Fort Beausejour in Nova Scotia, using two further regiments to be newly raised in America.

Newcastle, in late 1754, went out of his way to point out that the expedition was Cumberland’s project.

The British Government managed to restrict its financial involvement in the American Expedition, at least in theory. The King refused to countenance the use of regiments from the British establishment, fearing that they might be needed in the event of war with France. Newcastle’s hand can perhaps be seen in this decision. The two regiments selected for America, Halkett’s 44th and Dunbar’s 48th, came from the Irish establishment, where they were paid for under the Irish military budget. Finances in Ireland were not Newcastle’s concern.

The two regiments would not become the financial liability of the British Government, even when they left Ireland and were augmented to a full war establishment. These two regiments together with the new regiments of Shirley and Pepperell to be raised in America could not become the financial responsibility of the British Government because this would take the size of the Army on the British Establishment over the limit laid down by the Mutiny Act.

The plan was that the two ‘Irish’ regiments would pass from the liability of the Irish Exchequer to that of the provincial governments in America. The two regiments raised in America would be the responsibility of the provincial governments from their raising.

The stores required for Braddock’s force were extensive and came from the Board of Ordinance, so that they were a charge on government funds. But there was no sign that any of this equipment was especially manufactured rather than issued from existing stocks and therefore no additional charge was incurred for the British Government in this respect.

The pay of the Royal Artillery and Royal Navy personnel for the expedition was a central government charge, but these personnel were already on the establishment and not especially recruited.

The provision made in the orders and directions for the campaign was that the American Colonies would become responsible for financing the military operations in America by way of a central fund contributed to by all the colonies. It is explicitly set out in an instruction to Braddock dated 25th November 1754 (see Pargellis’s document ‘Private Instructions for Major-Gen Braddock’) that this fund was to cover the cost of raising the 3,000 recruits required to bring the two regiments from Ireland up to a war establishment and to raise the two new regiments of regulars, Shirley’s and Pepperell’s, and any provincial regiments or companies. The fund was also to finance the purchase and movement of supplies for the troops on operations and any other incidentals.

Colonel Sir William Pepperell, the colonel of one of the two new regiments to be raised in America. Pepperell was credited with the capture of Louisburg in King George’s War

A sum of £10,000 in specie was provided to Braddock as a reserve. However this sum was not directly funded by the British Government. It was raised by way of a loan from John Hanbury, the London merchant and member of the Ohio Company.

John Hanbury and a Mr Thompson, who may have been Hanbury’s business partner in London, were appointed the contractors to the force to be sent to Virginia.

Finances and the American Colonies:

When the plan was compiled for the military operations in North America to be financed by way of a central fund paid into by the American colonies, the British Government can have had little understanding of the realities of American provincial politics.

Several attempts were made by American governors during the 1750s to persuade the assemblies of their colonies to contribute to the cost of action against the French with a singular lack of success.

The small amount of funds voted by the Virginia Assembly limited the size of the force available to Dinwiddie for the attempt to build and hold the fort at the Ohio Forks in 1753.

In Pennsylvania and Maryland, the proprietors of the colonies prevented their governors from agreeing to any form of tax that imposed a charge on the substantial proprietary landholding. This brought stalemate with the Assemblies, which refused to agree to taxation measures from which the proprietors were exempt, even when the measures were for the defence of the colonies.

In North Carolina, there was less of an awkward proprietor-assembly standoff. The governor of the colony, Arthur Dobbs, was a member of the Ohio Company and close collaborator with Dinwiddie. North Carolina voted a sum of £6,000 for the central fund.

The New York Assembly voted in October 1754 to contribute £5,000, and the Maryland Assembly finally voted to contribute £6,000.

These sums were inadequate to finance the military operations, even as planned. In the event, expenditure far exceeded what was originally envisaged. Braddock was forced to spend on wagon transport many times the expected amount. He came near to running out of money in June 1755 at Fort Cumberland (Will’s Creek), leading to George Washington’s dash to Williamsburg to borrow £8,000.

The previous section on Braddock’s defeat on the Monongahela in 1755 is Part 3: The Planning of General Braddock’s expedition.

The next section on Braddock’s defeat on the Monongahela in 1755 is Part 5: Braddock’s regiments, Halkett’s 44th and Dunbar’s 48th, and his departure for Virginia.

To the French and Indian War index