The account of General Braddock’s expedition to Fort Duquesne in 1755:

Part 10: ‘The Battle on the Monongahela on 9th July 1755.

Emanuel Leutze’s “Washington at the Battle of the Monongahela.” The British troops portrayed are wearing Revolutionary War uniforms: Death of General Edward Braddock on the Monongahela River on 9th July 1755 in the French and Indian War

The previous section on Braddock’s defeat on the Monongahela in 1755 is Part 9: Braddock’s army’s march from Little Meadows to the Monongahela River May to June 1755.

The next section on Braddock’s defeat on the Monongahela in 1755 is Part 11: The 2nd Earl of Albemarle, the Duke of Cumberland and Edward Braddock’s expedition to capture Fort Duquesne in 1755.

To the French and Indian War index

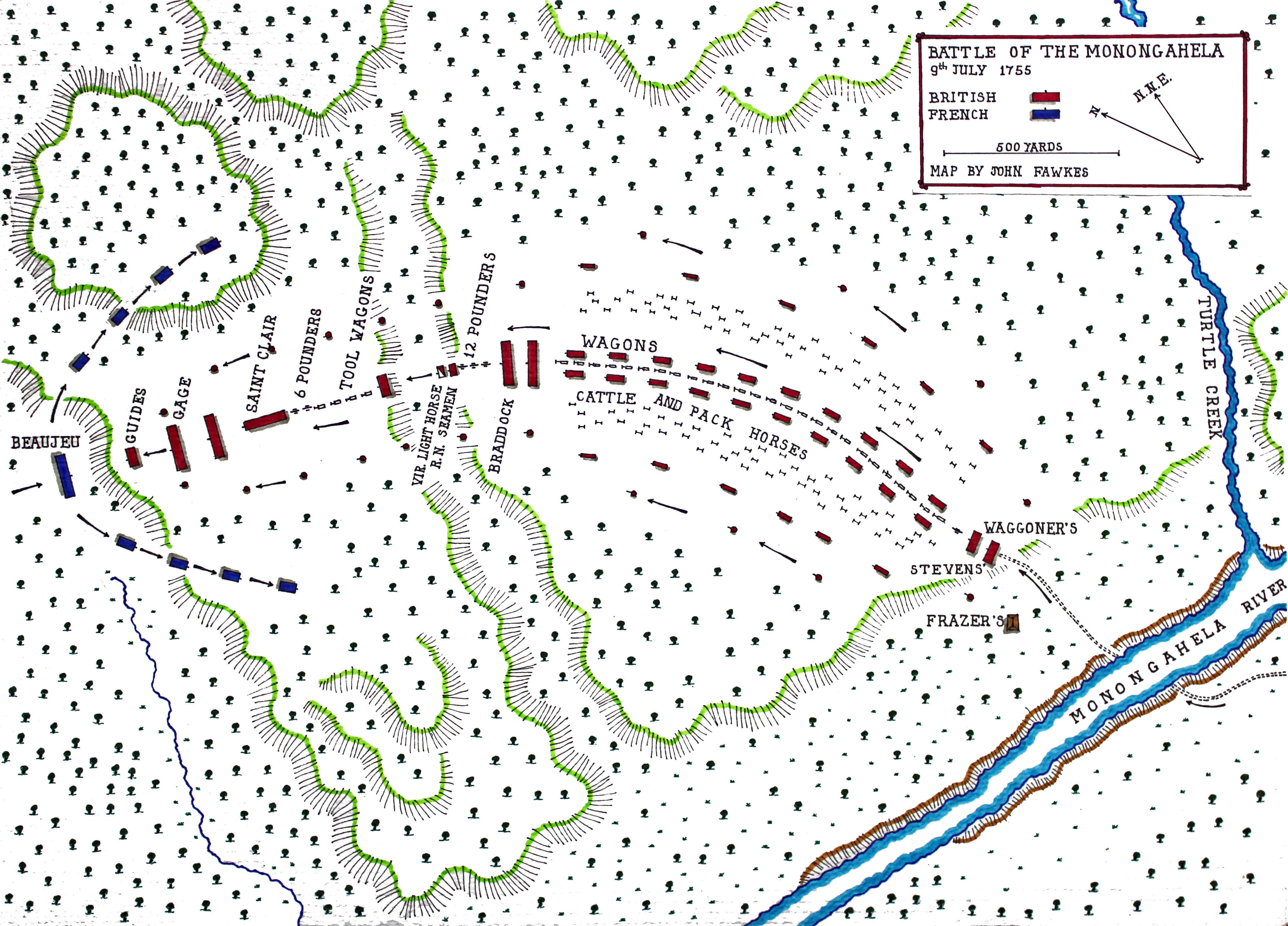

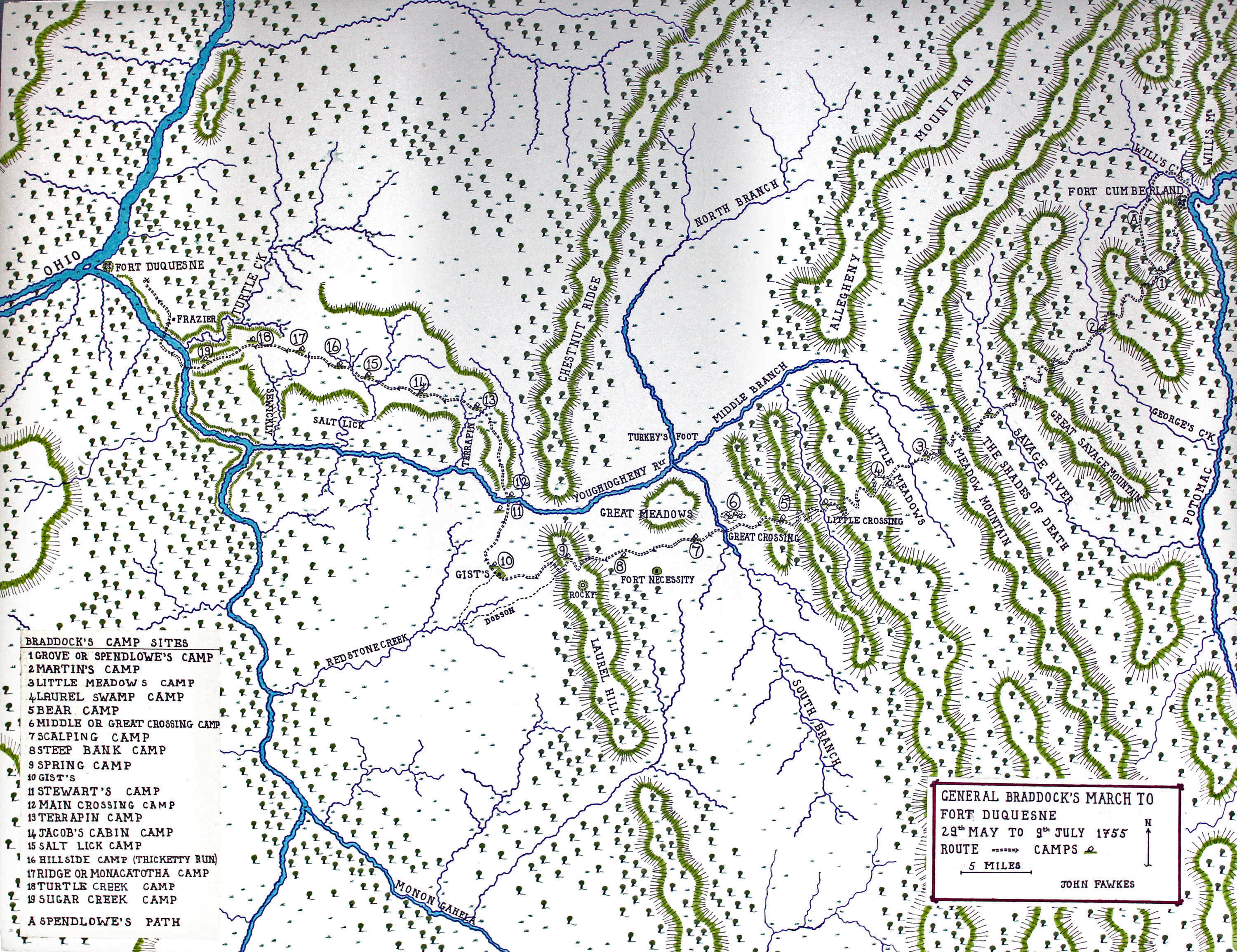

Map of General Braddock’s march from Fort Cumberland to Fort Duquesne on the Monongahela River, May to July 1755, showing A Spendlow’s Path and camps at 1 Grove 2 Martin’s 3 Little Meadows 4 Laurel 5 Bear 6 Great Crossing 7 Scalping 8 Steep Bank 9 Spring 10 Gist’s 11 Stewart’s 12 Main Crossing 13 Terrapin 14 Jacob’s 15 Salt Lick 16 Hillside 17 Ride 18 Turtle 19 Sugar: Map by John Fawkes

The Army’s formation for the final march on 9th July 1755:

Advanced party (commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Gage):

Party of ‘Guides’ comprising a group of around 10 Native Americans led by Chief Monocatotha and 6 mounted soldiers of Captain Robert Stewart’s Troop of Virginia Light Horse.

The senior grenadier companies of the 44th and 48th Regiments and Captain Gates’ New York Independent Company.

Two 6 pounder field guns with their crews and ammunition carts (after the Monongahela River crossing these two field guns and their wagons moved behind Sir John Saint Clair’s road building party).

100 battalion soldiers from the 44th and 48th Regiments commanded by Captain Cholmley of the 48th forming the guard for the two 6 pounder field guns.

Colonel Sir John Saint Clair’s road building party comprising Captain Polson’s Company of Carpenters and Captain Peyrouney’s company of Virginia Rangers accompanied by the engineers McKellar and Gordon.

The road making party’s tool wagons

The Main Army (General Braddock)

Captain Robert Stewart’s Troop of Virginia Light Horse

Contingent of seamen and pioneers

Three 12 pounder field guns with ammunition carts

A company of Grenadiers

A van guard of battalion soldiers from the 44th and 48th Regiments commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Burton

The column of some 35 wagons in single file, 3 or 4 of them provision wagons, with the remaining body of troops from the 44th and 48th in files on each side and the cattle and carrying horses between the files and the flank guards in the woods.

A 12 pounder field gun with the ammunition carts of the artillery train.

Engineer Gordon records in his letter of 22nd July 1755 (Pargellis) that Braddock’s section of the army carried with it 4 howitzers and 3 coehorns in addition to the 6 and12 pounders.

The Rearguard

Captain Waggoner’s and Captain Adam Steven’s Companies of Virginia Rangers.

The length of the whole column was probably around ¾ mile. The rear of the army was still at the crossing of the Monongehela when the French and their Native American allies began the attack at the front.

Orme’s and McKellar’s maps of the battle show Braddock’s army as having flank guards at a distance from the main line of march on each flank from Gage’s force to the rear. Orme shows the main army as having inner flank guards of a subaltern and 20 men and outer flank guards of a sergeant and 10 grenadiers. Both these maps are in the Cumberland Papers at Windsor Castle and are similar in many respects. Both maps show Saint Clair’s working party in front of the two 6 pounders whereas Captain Cholmley’s batman states that he was part of the escort for these guns commanded by Cholmley and that they found it arduous going because the guns were ‘in front of the road making party’.

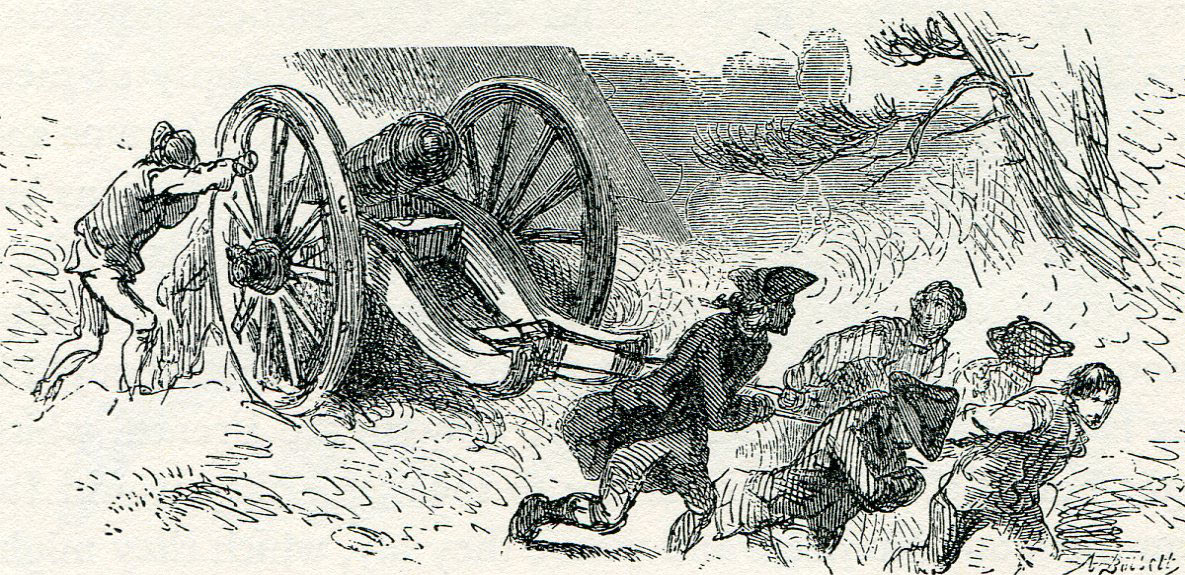

British and American troops dragging a 6 pounder field gun in General Braddock’s advance to the Monongahela in 1755

The March:

Braddock’s troops marched on the morning of 9th July 1755 with some anxiety. The march on 8th July had been difficult and involved crossing the Sewickley Creek or Long Run some twelve times. The army had encamped part of the way down a long valley that led to the Monongahela River. The march on the 8th had been conducted with all precautions against surprise, with parties of troops on each of the heights on either side of the valley. There was a general shortage of food. Captain Cholmley’s batman reported that some men had nothing to eat on 8th July.

Careful plans were laid for the march on the next day that would take the army up to Fort DuQuesne, the French fort that was the army’s destination.

Sir John Saint Clair, the deputy quartermaster general, proposed to Captain Orme that a party be sent on to reconnoitre the fort. Orme records that Sir John made this suggestion to him but not to Braddock. Unfortunately this militarily sound proposal was not taken up. The deputy quartermaster general, a Scotsman, was not one of the officers whose opinion was listened to by Braddock and his immediate entourage.

The advice of Christopher Gist, the general’s guide, was that it was too hazardous to march along the northern bank of the Monongahela, as there were steep cliffs over a narrow path along the riverbank. His advice was that the army should cross the Monongahela at the southern end of the valley, march along the southern bank of the Monongahela some 7 miles to the point opposite Frazier’s Cabin just beyond the junction of Turtle Creek and the Monongahela River, cross to the north bank and continue the march through the forest to Fort Duquesne.

A soldier of the 48th Foot on the march to Fort DuQuesne in Western Pennsylvania. The British soldiers left their uniform coats in Alexandria and marched in their waistcoats: Illustration by Mark Dennis of Petaluma and St Andrews.

It was generally felt in Braddock’s army that the French would finally oppose the advance at one of the positions that had to be passed to reach Fort Du Quesne; perhaps in the woods during the advance to the river or at the first crossing of the Monongahela to the south bank or at the crossing back to the north bank. It seemed inconceivable that there would not be a fight at one of these points. It is an indicator of the senior officers’ expectation of French resistance that all troops were ordered to load with ball, as opposed to just pickets and certain guards as on earlier days in the march.

The army was to be led by the advance party under Lieutenant Colonel Gage and the working party of carpenters and pioneers to cut the road, supervised by Colonel Sir John Saint Clair and the three engineers who had performed this unrewarding function faithfully during the whole march.

Gage’s leading troops left Turtle Camp at 2am to march down the final section of the valley to the Monongahela River. The main section of the army followed at 4am.

Gage’s party reached the Monongahela River and crossed to the south bank. They marched west along the southern bank for some seven miles. Cholmely’s party had particular difficulty manhandling the two 6 pounders through the woods and scrub as the road making party was behind them.

The point at which Braddock’s army would cross back to the north bank of the Monongahela was immediately to the west of where Turtle Creek joins the main river, marking the end of the cliff along the northern river bank. Fraser, the trader and erstwhile officer of the Virginia Regiment, had his cabin here.

French Regiment La Marine: the few regular French troops at Fort DuQuesne were from this regiment: co-incindentally the regimental number was 44th.

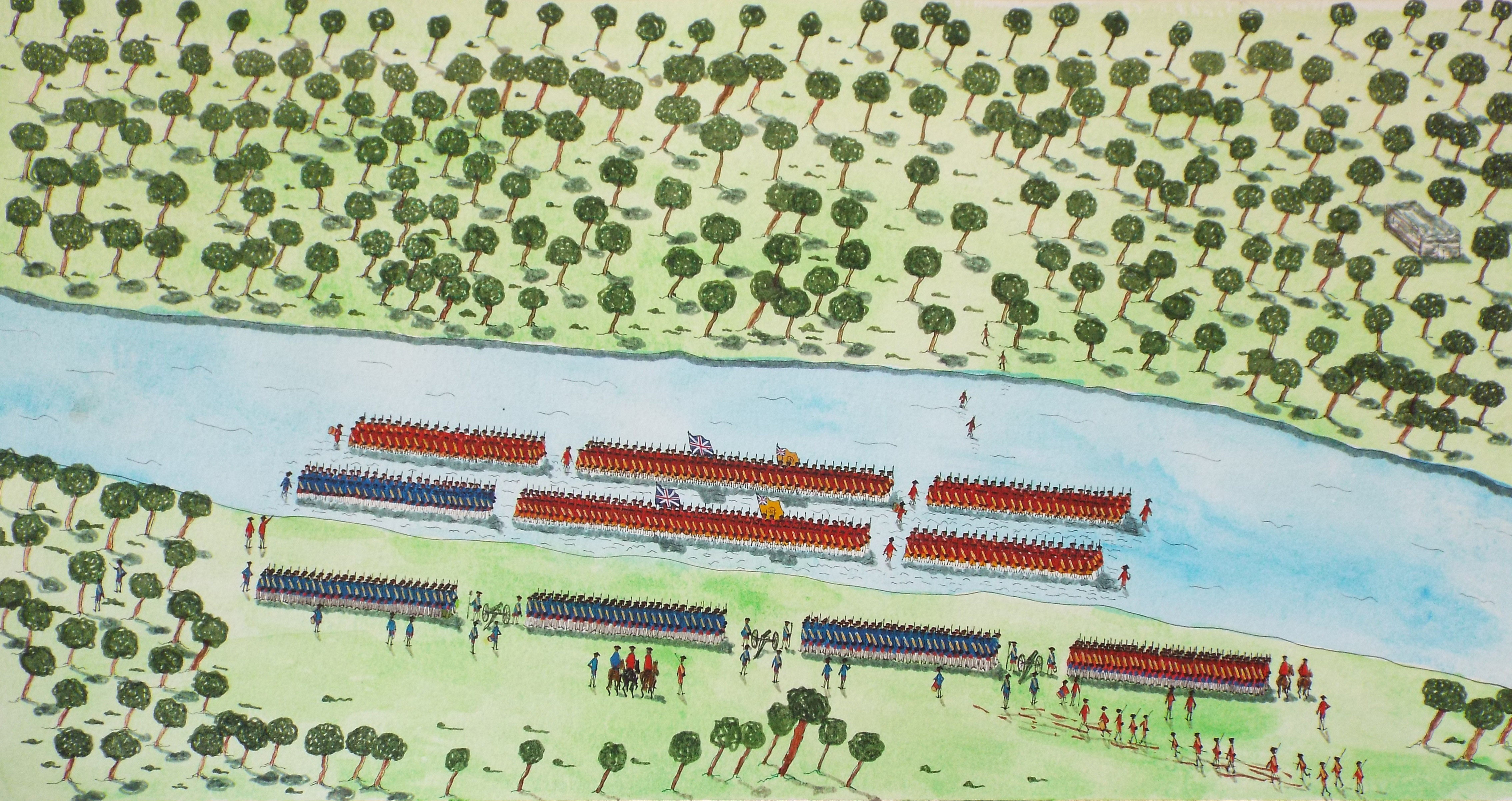

Captain Cholmley’s batman described how Gage’s force formed order of battle on the southern bank and crossed the 300 yards of the Monongahela, wheeling the two 6 pounder field guns through the water, which he described as being knee-high. On the far side the soldiers found a precipitous bank, described by Engineer Gordon as at least 12 feet high, that had to be broken down to get the guns and waggons out of the river. During this process Cholmley’s batman stated that ‘some saw Indians and some did not’.

The expectation in the British army was that this was the last opportunity for the French and their Native American allies to mount a defence against them if there was to be any resistance.

Gage’s troops moved across the river in order of battle and scrambled up the far bank. There were no French troops or Native Americans to resist them.

By 9.30am Captain Cholmley’s artillery guard was also across the Monongahela and waiting on the north bank with sentries posted. Captain Cholmeley’s batman described that he ate his breakfast, ‘although only 1 soldier in 20 had anything to eat’.

At 10.30am the deputy quartermaster general’s working party came across the river.

At 11am the main army came up and began to cross the river, as working parties cut down the high riverbank on the north side.

Gage’s party and the two 6 pounder guns and escort moved off towards Fort DuQuesne, followed by Saint Clair’s party. Captain Cholmeley’s batman recorded: “So we began our march again beating the Grenadier’s March all the way”

It is clear from this description and others that once Braddock’s army crossed the Monongahela River there was a change of atmosphere from the earlier apprehension of battle. Engineer Gordon recorded: “Every one who saw these Banks, Being Above 12 feet perpendicularly high Above the Shire, & the Course of the River 300 yards Broad, hugg’d themselves with joy at our Good Luck in having surmounted our greatest Difficultys, & too hastily Concluded the Enemy never wou’d dare to Oppose us.”

Lieutenant Colonel Gage’s advanced guard of General Braddock’s army crossing the Monongahela River for the final march to Fort DuQuesne on 9th July 1755: by John Fawkes

Once they had crossed the river the various components of Braddock’s column moved off into the forest, turning west towards Fort DuQuesne as they passed Frasier’s Cabin. The fifes and drums played and the atmosphere would perhaps best be described as jaunty.

A number of more experienced soldiers associated with Braddock’s army had at various times urged the establishment of fortified bases as the army moved forward, to provide points of defence in case of difficulty. Governor Sharpe and Sir John Saint Clair made this suggestion. No doubt others did as well, perhaps including the Virginia officers who had fought in 1754. This advice was rejected, on occasions contemptuously, by Braddock and Orme. In his uncompromising refusal Braddock may well have been influenced by the Duke of Cumberland’s caustic comment that the American colonials seemed over-fond of forts.

At this late stage ordinary military prudence might have caused General Braddock to establish a position on the Monongahela and to hold the column of transport back while a force moved forward to establish the true situation at Fort DuQuesne. As it was, Braddock’s officers seem to have abandoned many of the precautions adopted during the march so far.

The anonymous letter written to Cumberland and ascribed by Pargellis to Captain Gabriel Christie, Saint Clair’s deputy stated: “… One thing cannot escape me, which is, that had our march been executed in the same manner the 9th as it was the 8th, I shou’d have stood a fair chance of writing from fort Du Quesne, instead of being in the hospital at Wills’s Creek.”

This is presumably a reference to the deployment of large forces to the heights on the army’s flanks during the march on 8th July, with troops being sent to examine and occupy any eminence or position that might hide an ambush, precautions fatally absent on the following day.

Several accounts record that the close scrubby vegetation that had made the march so difficult so far, as the army began its march away from the river, gave way to open forest with very little under vegetation. One recorded that it would have been possible to drive a carriage through the woods.

The Battle on the Monongahela on 9th July 1755:

As Braddock’s relaxed soldiers marched to within seven miles of Fort DuQuesne a force of French soldiers and allied Native Americans came down the path towards them. The best estimates put the size of this force at around 300, mostly Native Americans with a small number of French Canadians and French regular troops.

Engineer Gordon recorded how the battle began: “Gage’s party march’d By files four Deep our front had not Got above half a Mile from the Banks of the River, when the Guides which were all the Scouts we had, & who were Before only about 200 yards Came Back, & told a Considerable Body of the Enemy, Mostly Indians were at hand, I was then just rode up in Search of these Guides, had Got Before the Grenadiers, had an Opportunity of viewing the Enemy, & was Confirm’d By the Reports of the Guides & what I saw myself that their whole Numbers did not exceed 300.”

The French and Native Americans on seeing the British troops divided and ran down each of the British flanks firing at the troops from the cover of the trees. Those coming down the British right flank took possession of an area of high ground that overlooked the British troops. The British flank parties each comprising an officer and twenty men were quickly overwhelmed.

The soldiers of Gage’s grenadier companies formed line with the front rank kneeling on the ground and opened fire, maintaining their fire for several minutes and suffering some ten or twelve casualties. They can have had few targets as the attackers had swiftly moved around their flanks in the cover of the trees. However one of earliest of the few French casualties was their commander Captain Beaujeu, dressed as a Native American except for the officer’s gold gorgette hanging around his neck, shot dead by Gage’s grenadiers.

The appearance of the Native Americans on the high ground to the right caused Gage to order his men to withdraw 50 or 60 paces, ‘where they confusedly formed again.’(Engineer Gordon) Many of the British officers were by this time casualties, being particular targets for the hostile fire.

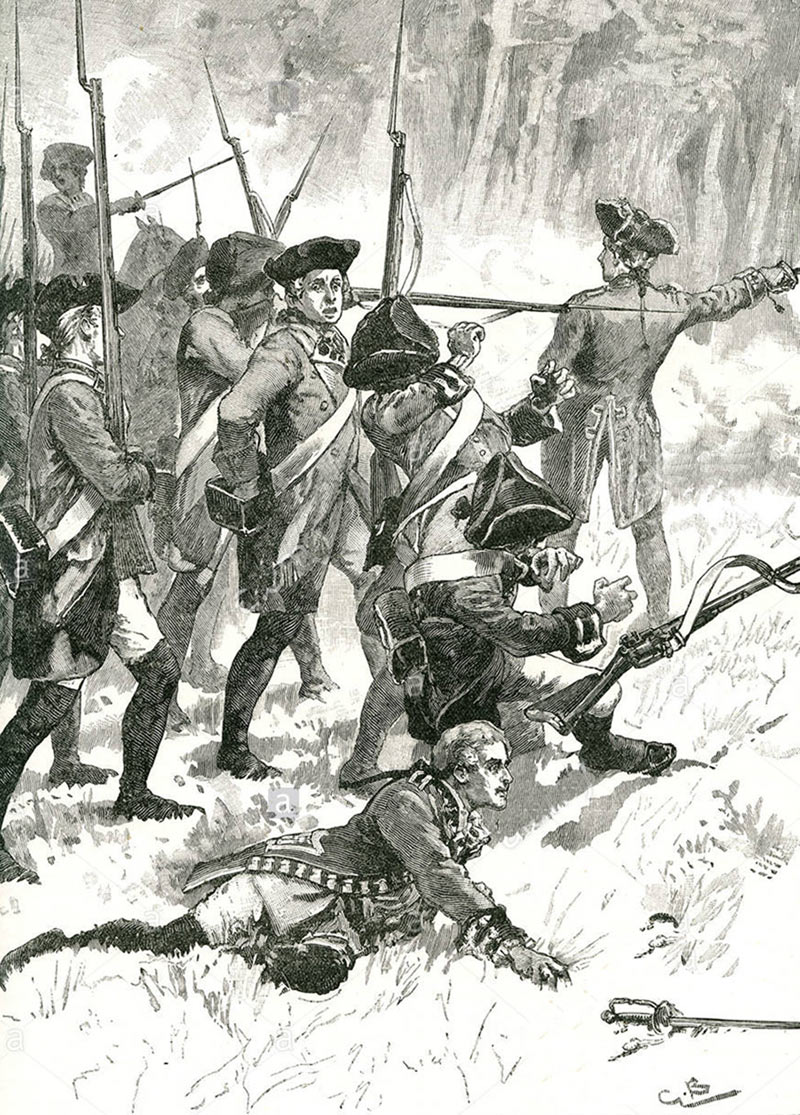

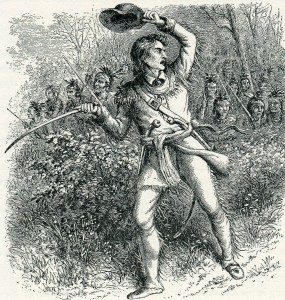

The French commander Beaujeu leads the first assault on General Braddock’s column before being shot dead

Captain Cholmley’s batman continued his account: “About half an hour after ten the working party came over the river and about at eleven the grand army begins to come over. As soon as they came to the river we rec’d orders to march on again. Sir John Sincklare asked Colonel Gage if he would take the two piece of cannon with us again. Colonel Gage answered, no sir I think not, for I do not think we shall have much occasion for them and they being troublesome to get forwards before the roads are cut. So we began our march again, beating the grannadiers march all the way, never seasing. There never was an army in the world in more spirits then we where, thinking of reaching Fort de Cain the day following as we was then only five miles from it. But we had not got above a mile and a half before three of our guides in the front of me above ten yards spyed the Indiens lay’d down before us. He immediately discharged his piece, turned round his horse cried, the indiens was upon us. My master called me to give me his horse which I tooke from him and the ingagement began. Immediately they began to ingage us in a half moon and still continued surrounding us more and more. Before the whole army got up we had about two thirds of our men cut of that ingaged at the first. My master died before we was ten minuits ingaged. They continualy make us retreat, they having always a large marke to shoute at and we having only to shoute at them behind trees or laid on their bellies. We was drawn up in large bodies together, a ready mark. They need not have taken sight at us for they always had a large mark, but if we saw of them five or six at onetime was a great sight and they either on their bellies or behind trees or runing from one tree to another almost by the ground. The genll had five horses shot under him. He always strove to keep the men together but I believe their might be two hundred of the American soldiers that fought behind trees and I belive they did the moast execution of any. Our Indians behaved very well for the small quantity of them. …”

Braddock hearing the outburst of firing from the vanguard rushed forward with his ADCs leading a substantial force from the main army. The anonymous officer described this advance: “upon the alarm of the advance fire, the General immediately rode to the front and his aid-du-camps after him, some officers after them, and more men without any form or order but that of a parcel of school boys Coming out of school- and in an instant, Blue, buff and yellow were intermix’d (that is the Virginian Rangers, 44th and 48th).”

Some accounts of the battle have Braddock ordering Burton with the vanguard of the main army forward while he and his ADCs assembled the main force from its position along the flanks of the wagon column.

The vanguard grenadiers with Saint Clair’s and Cholmeley’s parties again began to retire but met the men of the main army rushing forward.

Burton’s advancing vanguard or Braddock’s main army, or both, opened fire on Gage’s retreating men inflicting significant casualties on them, particularly on the two Virginian companies which are likely to have been the first troops they saw.

James Wolfe in his letter commenting on Braddock’s defeat stated that the lack of proper discipline in British infantry regiments made them liable to fire on anybody, friend or foe.

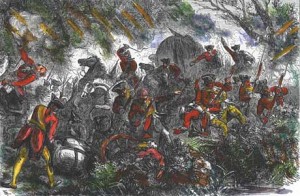

General Braddock’s troops ambushed by the force of French and Native Americans at the Monongahela River on 9th July 1755

Braddock’s troops formed a mass up to 20 deep, firing as quickly as they could reload, but without having a target. Several officers commented after the battle that they only ever saw one or two Native Americans at a time during the fight.

The Royal Artillery crews of the two 6 pounders with the advanced guard seem to have stayed to serve their guns and died with them.

The repeated firing of muskets and field guns generated a heavy pall of smoke that was hemmed in by the tree canopy, preventing the soldiers from seeing who they were firing at and further encouraging the general sense of panic.

General Braddock ordered Burton to take a body of men and storm the hill to the right, the source of some of the most devastating enemy fire.

Engineer Gordon recorded: “The General Order’d the officers to Endeavor to tell off 150 men, & Advance up the hill to Dispossess the Enemy, & another party to Advance on the Left to support the two 12 pounders & Artillery people, who were in great Danger of Being Drove away By the Enemy, at that time in possession of the 2 field pieces of the Advanc’d party. This was the General’s Last Order; he had Before this time 4 horses killed under him, & now Receiv’d his Mortal wound. All the Officers us’d their Utmost Endearvors to Get the men to Advance up the hill, & to Advance on the left to support the Cannon. But the Enemy’s fire at that time very much Encreasing, & a Number of officers who were Rushing on in the front to Encourage the men Being killed & wounded, there was Nothing to Be seen But the Utmost panick & Confusion amongst the Men; yet those officers who had Been wounded having Return’d, & those that were not Wounded, By Exhorting & threatening had influence to kep a Body about 200 and Longer in the field, but cou’d not perswade them Either to Attempt the hill again, or Advance far Enough to support the Cannon, whose officers & men were Mostly kill’d & wounded. The Cannon silenc’d, & the Indian’s shouts upon the Right Advancing, the whole Body gave way, & Cross’d the Monongahela where we had pass’d in the Morning. With great Difficulty the General & his Aid de Camps who were both wounded were taken out of a Waggon, & hurryed along across the River;

Burton and his officers tried to lead the soldiers to the attack but they would not advance out of the main body and eventually Burton was hit and most of his officers killed or wounded as they tried to give their men a lead by rushing into the woods.

The British force lost cohesion with officers, some mounted, attempting various initiatives to try and resolve the situation, with no response from the panic stricken soldiers, who simply discharged their muskets.

During the three hours of the battle the French Native Americans remained largely unseen, firing from behind cover and advancing as the British fell back on the column of wagons. Braddock had four horses shot from under him and was hit by a round which struck his arm and penetrated his chest, fatally wounding him. Many of the other officers were wounded: Orme, Gage, Burton and Saint Clair. Halkett and his son were killed, as were Cholmley, Tatton, Polson, Peyrouney and many of the junior officers.

Several attempts were made to advance and rescue the two 6 pounders of the advance party, but the groups were shot down, in part by other British soldiers firing into the gloom at anyone they could see in the trees.

The army was pressed back on the wagon column where panic stricken drivers, Daniel Boone among them, cut the horses free and rode back to the ford over the Monongahela and crossed the river, leaving the wagons to the French.

Washington and Orme persuaded some soldiers by offering them money to assist in getting the wounded Braddock into a cart and back across the river.

It is probably at this point that the Virginia Rangers of the rearguard commanded by Waggoner and Stevens were directed by their Virginian officers to take cover in the trees rather than huddle in the pathway.

There was a mad scramble by the soldiers to get away from the scene of the battle and back across the Monongahela.

Engineer Gordon recorded his escape: “I am a Good Deal hurt in the Right Arm, having Receiv’d a Shot which went thro’ & shatter’d the Bone, half way Between the Elbow & the wrist; this I had Early, & altho’ I felt a Good deal of pain, yet I was too Anxious to allow myself to Quit the field; at the last my horse having Receiv’d three shots, I had hardly time to shift the Saddle on another without the Bridle, when the whole gave way. The passage that was made thro the Bank in the Morning, I found Choack’d up; I was oblig’d to tumble over the high Bank, which Luckily Being of Sand, part of it fell along with me, which kept my horse upon his feet, & I fortunately kept his Back. Before I had got 40 yards in the River, I turn’d about on hearing the Indians Yell, & Saw them Tomohocking some of our women & wounded people, others of them fir’d very Briskly on those that were then Crossing, at which time I Receiv’d Another Shot thro’s the Right Shoulder. But the horse I Rode Escaping, I got across the River, & soon came up with the General, Coll; Burton, & the rest of the officers & men that were along with them, & Continued along with them in the Utmost pain, my wounds not having Been Dress’d until I came to Guest’s.”

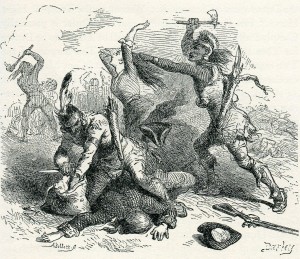

Indians scalping British troops and women in the attack on General Braddock’s army 9th July 1755 on the Monongahela

Most of the French-led Native Americans remained on the main battlefield, tomahawking and scalping the wounded. Some 50 followed the British to the river and fired into the mass of soldiers as they re-crossed the Monongahela, but none followed across the river. Nevertheless the panic-stricken soldiers kept going.

At a point about half a mile back along the southern bank of the Monongahela Lieutenant Colonel Burton attempted to rally some of the troops and take up a position. None of the soldiers would stay and the retreat continued.

Braddock was brought off the field by a group of officers, Orme, Stewart, Morris and Washington in particular, and conveyed back to Gist’s in a cart.

Colonel Dunbar with his following force was at Rock Camp when the survivors from Braddock’s force began to arrive, led by the mounted wagon drivers. Orme arrived with the dying Braddock at about 10pm on 10th July 1755.

As soon as they heard of the disaster Dunbar’s troops began to desert and make their way back to Will’s Creek or off into the country and the remainder ceased to be amenable to discipline. Dunbar was widely blamed for what now happened. The army began a wholesale destruction of the stores and equipment that remained, including burning and burying the guns and carriages. Artillery was at a premium in America and the loss of the guns was a major blow.

Dunbar’s subsequent explanation was that there were not the horses to bring the artillery and equipment back from Rock Fort. It is apparent that even if Dunbar had been of a mind to try and hold a position that far forward he did not have soldiers who were prepared to stay and such wagons and horse teams as there were were needed to convey the large number of surviving wounded.

Mortally wounded, General Edward Braddock is carried back from the Monongahela to Great Meadows Camp where he died on 12th July 1755: picture by Alonzo Chappel

On 13th July the army retreated to the Great Meadows Camp where General Braddock died. He was buried and his grave site carefully covered over to avoid his body being dug up and desecrated.

The burial of Major General Edward Braddock after the battle on the Monongahela, shown in an idealised print. After the burial, waggons were driven across the site to ensure it could not be found by the French and Indians presumed to be pursuing the beaten army.

Dunbar continued the retreat to Fort Cumberland arriving on 22nd July 1755. The survivors from Braddock’s force were without arms, equipment or in many cases proper clothing.

On 2nd August 1755 Dunbar marched out of Fort Cumberland for Philadelphia to ‘go into Winter Quarters,’ leaving the western counties of Maryland, Pennsylvania and Virginia open to a wave of Native American assaults inspired by the French.

Idealised post US Independence picture ‘Washington at the Battle of the Monongahela’. No British officer or soldiers are shown, other than the wounded General Braddock: Death of General Edward Braddock on the Monongahela River on 9th July 1755 in the French and Indian War

The previous section on Braddock’s defeat on the Monongahela in 1755 is Part 9: Braddock’s army’s march from Little Meadows to the Monongahela River May to June 1755.

The next section on Braddock’s defeat on the Monongahela in 1755 is Part 11: The 2nd Earl of Albemarle, the Duke of Cumberland and Edward Braddock’s expedition to capture Fort Duquesne in 1755.

To the French and Indian War index