The account of General Braddock’s expedition to Fort Duquesne in 1755:

Part 3: The Planning of General Braddock’s expedition

Grenadiers of the 1st, Coldstream and 3rd Foot Guards in1751: picture by David Morier: Death of General Edward Braddock on the Monongahela River on 9th July 1755 in the French and Indian War

The previous section on Braddock’s defeat on the Monongahela in 1755 is Part 2: The deterioration in relations between Britain and France in America

The next section on Braddock’s defeat on the Monongahela in 1755 is Part 4: The appointment of Edward Braddock as commander-in-chief in America

To the French and Indian War index

The British Government and the Duke of Cumberland:

In early 1754 there were changes in government in London. The ‘Whig’ Duke of Newcastle became Prime Minister of Great Britain, following the death of his brother Henry Pelham, on 6th March 1754. Lord Holderness took the post of Secretary of State for the Southern Department, with responsibility for the American colonies in tandem with the President of the Board of Trade, the ministerial post of the Earl of Halifax.

The Duke of Newcastle: portrait by William Hoare: Death of General Edward Braddock on the Monongahela River on 9th July 1755 in the French and Indian War

Government ministers and departments had taken little interest in the American colonies prior to the upheavals of the 1750s. The primary concern was affairs on the European continent. With the news of Washington’s capitulation at Fort Necessity, received in London in August 1754, everything changed and America became the focus of interest. The Duke of Cumberland, second son to King George II, and, as Captain General, the head of the British Army, announced “Rather than lose one foot of ground in America, I will oppose the enemies of my country in that part of the world myself.” Resisting the French in America, almost overnight, became a patriotic duty.

The Newcastle Government seeks information on North America from Gates and Hanbury:

The Ministry in London looked around to see who could give them the information they needed on circumstances in America and in particular in Virginia. According to Horace Walpole, the first candidate was his godson, Captain Horatio Gates, on leave in England from his post as Captain in command of one of the Independent Companies in New York.

Gates, again according to Walpole, pointed out that his post was in New York and that he knew little about circumstances in Virginia or anywhere else in the American colonies.

The Government turned to their alternative expert, John Hanbury, agent for the Virginia plantation owners and member of the Ohio Company. John Hanbury supported Dinwiddie’s assessment of the crisis; that the priority was to drive the French from the Ohio Forks.

The influence of the Ohio Company on British war policy in North America seemed to be complete. Walpole wrote “and at [Hanbury’s] recommendation [the government] determined upon Sharpe, the Governor of Virginia, for their General. They told the King he had served all the last war, though he had never served, and that the Duke had a good opinion of him:….”

There is confusion in Walpole’s statement, perhaps reflecting the incomplete understanding by the London establishment of things American. Horatio Sharpe was lieutenant governor of Maryland not Virginia and he had in fact served during King George’s War. Sharpe was the first choice of the London Government for the command in America, but that was before the Duke of Cumberland put his stamp on policy.

Horatio Sharpe appointed Commander-in-Chief in North America:

In the late summer of 1754, the Government in London sent two commissions to Horatio Sharpe at Baltimore in Maryland, one appointing him lieutenant colonel and the other appointing him the commander-in-chief in North America. In the event neither commission took effect. Even so Sharpe was to be an important player in Braddock’s campaign.

Horatio Sharpe had been appointed Lieutenant Governor of Maryland in early 1753. Sharpe’s older brother was the Master of the Temple Church in London and one of the guardians of the young Lord Baltimore, the proprietor of Maryland. Sharpe’s brother was also a chaplain to Frederick, Prince of Wales, and to Frederick’s son, the future King George III.

The Prince of Wales, until his death in 1753, was in dispute with his father, King George II, and his younger brother, the Duke of Cumberland. The Prince of Wales’ residence, Leicester House, was the centre for the Tory opposition to the Government and the King. Sharpe was therefore likely to have been an object of suspicion for Cumberland and consequently of Braddock and his staff. This suspicion may have been mitigated by Sharpe’s pleasant personality and obvious competence.

It would be Sharpe’s advice that Braddock approach the Ohio Forks with care and build forts on the way; advice that was not followed. It was Cumberland’s view that the colonists appeared to be too fond of forts; a view born of Cumberland’s lack of understanding of the dynamics of warfare in the extensive and largely uninhabited forests of North America.

Sharpe had experience as a junior army officer. He had been commissioned into the Royal Welch Fusiliers on 2nd February 1740. He is likely to have fought at the Battle of Dettingen in 1743 and may have fought at the Battle of Fontenoy in 1745. He was promoted captain into Powlett’s Marines in 1745 and served in the West Indies. Lady Edgar, in her book on Sharpe, states that Sharpe served in the 20th Regiment with James Wolfe, the British general who captured Quebec from the French in 1759. It may be that on the reduction of the Marines in 1748 Sharpe bought a commission in the 20th. James Wolfe was the lieutenant colonel of the 20th from 20th March 1750 to 1756, when he became the colonel of the 20th. Interestingly, Lord Bury, the eldest son of the Governor of Virginia, the Earl of Albemarle, was colonel of the 20th from 1746 to 1755.

James Wolfe was in correspondence with someone knowledgeable in America at the time of Braddock’s defeat, although it is not revealed who. It may be that his correspondent was Sharpe. Wolfe’s letter, while circumspect, is a contemporary document of interest on the reasons for the collapse of Braddock’s army (the text is quoted in full in a later part).

Newcastle expresses the Government’s fear as to French intentions:

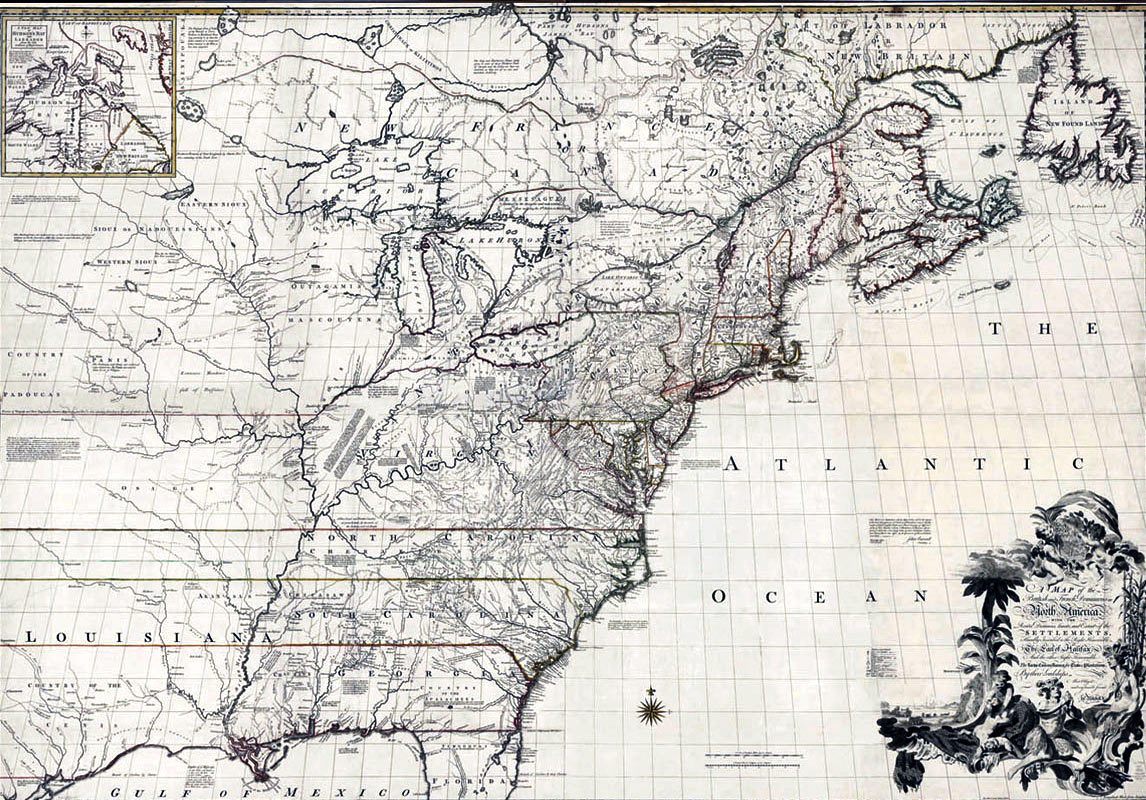

On 5th September 1754 the Prime Minister the Duke of Newcastle, wrote to Lord Albemarle, then British Ambassador in Paris, saying “All N. America will be lost if these practices are tolerated, and no war can be worse to this country than the suffering such insults as these. The truth is the French claim almost all N. America except a Lisière to the sea to which they would confine all our Colonies and from whence they may drive us whenever they please or as soon as there shall be a declared war. But that is what we must not, we will not, suffer.”

The practices Newcastle was referring to were the building by the French of Fort Duquesne at the Ohio Forks and the French seeing off Trent, Ward and Washington. The sentiments in his letter precisely reflected the urgings of Dinwiddie.

William Augustus, Duke of Cumberland: picture by David Morier: Death of General Edward Braddock on the Monongahela River on 9th July 1755 in the French and Indian War

The Government consults the Duke of Cumberland:

With the apparent need for military action, King George II ‘permitted’ the Government to consult the Captain General of the British Army, his younger son the Duke of Cumberland. This ‘permission’ was likely to have been a requirement by the King.

Cumberland’s assessment of what was needed was concise: military action to take the Ohio Forks and in the three other areas of confrontation with the French; Fort Beausejour in Nova Scotia, Crown Point at the southern end of Lake Champlain and Fort Niagara between Lakes Ontario and Erie. Cumberland recommended the appointment of a viceroy commander-in-chief in America, his candidate being the Earl of Albemarle. Cumberland also advised the dispatch of two regiments of regular foot and a draft of Foot Guards non-commissioned officers to train the Provincial levies.

Map of North East America in 1755: Death of General Edward Braddock on the Monongahela River on 9th July 1755 in the French and Indian War

The King vetoed the viceroy and the draft of Foot Guards NCOs. The King stated that the two regiments of foot were to come from the Irish establishment, not the British, due to his apprehension over a possible French attack on Hanover in the event of war. Otherwise Cumberland’s advice was quickly adopted. Instead of a viceroy there would be a commander-in-chief from the British regular army. Sharpe’s appointment as commander-in-chief in America was immediately annulled.

On 22nd September 1754, a key meeting took place between the Duke of Cumberland, the Prime Minister the Duke of Newcastle, the Lord Chancellor Lord Hardwicke, Admiral Anson First Lord of the Admiralty and Sir Thomas Robinson. Robinson recorded that Cumberland proposed the sending of two regiments of foot from the Irish Establishment and that attacks be launched against the French on the Ohio at Fort Duquesne, Crown Point, Fort Beausejour in Nova Scotia and Fort Niagara. The appointment of a relatively junior officer as the commander-in-chief in America was proposed.

Following this meeting Newcastle wrote to Lord Albemarle stating that the plan was all Cumberland’s.

Braddock is appointed Commander-in-Chief in America:

Thereafter Newcastle and his ministers effectively abdicated control of military affairs in North America to Cumberland. This was a significant step. The events in America in 1755 led directly to war with France and were a trigger for the Seven Years War across Europe and in the areas colonised by Britain, France and Spain; effectively a world war. Cumberland was at the height of his influence and was answerable only to his father the King. The politicians in Britain took a back seat in the rush to war.

Implementing the decisions reached proceeded with a speed not often encountered in mid-18th Century affairs.

Cumberland’s choice for commander-in-chief in America was Colonel Edward Braddock, a long serving officer of the Coldstream Guards in 1754 appointed colonel of the 14th Foot in Gibraltar. Braddock’s commissions as commander-in-chief in America and promotion to major general were dated 24th September 1754.

Two regiments of foot in Ireland were warned off for service in America; Sir Peter Halkett’s 44th Foot and Colonel Robert Dunbar’s 48th Foot. The Royal Artillery was instructed to provide a company of artillery.

Captain Augustus Keppel, Royal Navy, was appointed Commodore of the supporting naval squadron on 9th October 1754.

Captain Augustus Keppel, Royal Navy: portrait by Sir Joshua Reynolds: Death of General Edward Braddock on the Monongahela River on 9th July 1755 in the French and Indian War

The list of stores needed for the two regiments from Ireland, the Royal Artillery component and the troops to be raised in America was sent to the Board of Ordinance on 12th October.

Braddock was summoned from Marseilles in France, where he had landed during a Mediterranean trip on board a Royal Navy ship. Braddock arrived in London on 17th November. Cumberland and his adjutant, Colonel Robert Napier, gave Braddock his detailed instructions, both orally and in writing, on 24th November 1754.

The Jacobite threat in the 1750s:

Prince Charles Edward Stuart, grandson to King James II expelled from Britain in 1688, spent his life attempting to recover his grandfather’s throne. In the Jacobite rebellion of 1745, known as the ’45, Prince Charles landed in Scotland and raised the clans in rebellion, albeit unsuccessfully.

At the height of the ’45 Prince Charles led his army to Derby in a march on London before turning back. The Jacobites defeated the Government’s troops in two battles, Prestonpans and Falkirk, before being decisively beaten at the Battle of Culloden. The ’45 gave the British Government a very nasty fright.

The Duke of Cumberland, King George II’s younger son, played a major role in the suppression of the ‘45, winning the Battle of Culloden on 16th April 1746.

The Duke of Cumberland at the Battle of Culloden 16th April 1746 in the Jacobite Rebellion: Death of General Edward Braddock on the Monongahela River on 9th July 1755 in the French and Indian War

The Jacobite threat remained a concern for the Hanoverian monarchy of Kings George II and III up to the death of Prince Charles Edward Stuart in 1788.

The peaks of the Jacobite threat were the rebellions in 1715, 1719 and 1745. The last attempt at invasion in which Prince Charles was involved was in 1759. Prince Charles was known to have visited London secretly in September 1750 to gauge support for a further insurrection. He continued to drift from court to court in Europe, seeking assistance for his recovery of the British throne.

Prince Charles Edward Stuart: picture by William Mosman: Death of General Edward Braddock on the Monongahela River on 9th July 1755 in the French and Indian War

The Jacobites were a real threat to the Hanoverian monarchy throughout the 1750s. The threat was the more unsettling because the King could not know the extent to which there was genuine support for a Stuart monarchy in the British population.

There were many who, like Dr Johnson, claimed to be Jacobites, but would not take any positive action to support a Jacobite insurrection.

There were officers in the Army and Navy suspected of having Jacobite sympathies and mistrusted by Cumberland and the King.

At the end of the ‘45 Rebellion, General Oglethorpe, the founder of the colony of Georgia in America, was tried by court martial at Cumberland’s direction for having failed to press the retreating rebels with sufficient vigour during their retreat through the North of England.

Oglethorpe was known for his Jacobite sympathies and Cumberland suspected that Oglethorpe had deliberately permitted part of the rebel army to escape from his pursuing troops. Oglethorpe was acquitted, causing Cumberland and the King to suspect the loyalty of the senior officers who tried him.

It is in this period that the direction was given to remove all implements from the table before military and naval officers drank the Loyal Toast. This was to prevent officers with Jacobite sympathies from converting the Loyal Toast to ‘the King’ to a toast to King James, by passing the toasting glass over the water glass, thereby toasting the ‘King over the Water’, a covert reference to King James.

The Jacobite issue was significant in British America, particularly in the Middle and Southern Colonies; Pennsylvania, Maryland, Virginia, the Carolinas and Georgia, founded by Oglethorpe in 1733. The main sentence for rebels from Prince Charles’s defeated army after the ‘45 rebellion was transportation to the American colonies, where the convicted men were sold as indentured servants to the colonists. In addition, escaping members of the Jacobite army were suspected of fleeing to these colonies, particularly to Virginia, where there was a legacy of support for the Stuarts from the English Civil War in the previous century. The matter was further confused by the substantial reduction of the British Army and the Royal Navy following the Treaty of Aix la Chapelle in 1748 and the settlement of ex-soldiers and seamen, many of them Scots, in the American colonies. These men arrived at much the same time as escaping and transported rebels, so that it was not easy to distinguish between them. Following the ’45 any Scotsmen was liable to be seen as a rebel by the English.

Anti-Scots prejudice was a major theme in Braddock’s expedition. Several of the captains of the Virginia companies and other Virginian officers were Scotsmen who had arrived in the colony in the late 1740s; Stewart, Hogg, Stevens, Polson and Craik, and as a result were viewed with suspicion by Braddock and his English officers. Several were in fact fugitive Jacobites.

Dr James Craik: Death of General Edward Braddock on the Monongahela River on 9th July 1755 in the French and Indian War

Sir Peter Halkett, the colonel of the 44th Regiment, Colonel Dunbar, the colonel of the 48th Regiment (the 44th and the 48th were the two regiments allocated to General Braddock) and Sir John Saint Clair, the Deputy Quartermaster General in Braddock’s army were Scots and appear to have been treated with suspicion by Braddock and excluded from his ‘English’ inner circle, which included George Washington, seen by Braddock, Orme and the other English officers as an English Gentleman.

On 12th May 1755, while Braddock’s force was still at Wills’ Creek, matters reached such a state that Captain Polson demanded to be tried by General Court Martial to resolve the accusations being made against him that he was in rebellion against the Crown in the ’45. According to the record maintained by Captain Orme, a court martial was held but no result is recorded. As Captain Polson continued to serve and was killed on 9th July 1755, presumably the finding of the court martial was in his favour.

Sir John Halkett and Captain Tatton of the 44th had been prisoners of the Jacobite army after the disastrous defeat at Prestonpans on 21st September 1745 before being released on parole, and it can be envisaged that they may have recognised ex-members of the rebel army that held them.

As with Russian officers in the Stalinist era, the British officers may well have felt bound to prove their loyalty to the Crown and to avoid any course of action that might be misinterpreted, however justified at the time. A major criticism that can be levelled at Braddock is that he was in too much of a hurry to reach Fort Duquesne. Governor Sharpe’s advice to Braddock was that he should take his army through the forest in stages, building forts at intervals. It may have been a concern of Braddock’s that any apparent lagging in operations against the French would be interpreted by Cumberland and the King as treachery, as in the case of Oglethorpe in 1746.

William Hogarth’s picture “The Roast Beef of Old England”, painted in 1748, shows the gates of the French port of Calais. In the bottom right corner is a Scottish clansman, a fugitive from the Jacobite ’45 Rebellion of Prince Charles Edward Stuart. The clansman is identified by his tartan garb and the white Jacobite cockade in his bonnet. The picture combines actuality with allegory. The lurking Jacobite no doubt was in evidence when Hogarth went on his sketching trip to Calais, but also represents the national fear of a renewed Jacobite insurgency launched from the continent of Europe

The Second Earl of Albemarle and the Duke of Cumberland:

In the eyes of the House of Hanover, there were sections of the British population that could be relied upon as free from Jacobite sympathies, due to their backgrounds. Prominent among these was the family of van Keppel, a Protestant Dutchman who accompanied William of Orange from Holland in 1688, when, with Queen Mary, he assumed the British throne, displacing the Catholic Stuart, James II.

For his services, King William made van Keppel the Earl of Albemarle. Albemarle’s son, the Second Lord Albemarle, entered the British Army in 1717. In keeping with his status, Lord Albemarle was commissioned as a captain and substantive lieutenant colonel in the Second Foot Guards, the Coldstream Guards. Officers in the Foot Guards held substantive rank at least one higher than their regimental appointment: hence although Braddock’s aide de camp, Robert Orme, was a lieutenant in the Coldstream, he bore the substantive rank of captain.

2nd Earl of Albemarle: portrait by Charles Philips: Death of General Edward Braddock on the Monongahela River on 9th July 1755 in the French and Indian War

The selection of the Coldstream Guards for young Lord Albemarle in 1717 will have been no accident. The Coldstream was formed from two regiments of Cromwell’s New Model Army at the time of the Restoration of the Stuart Monarchy in 1660 by General Monk, a key supporter of the Restoration and an erstwhile general in the New Model Army of Oliver Cromwell.

The Coldstream possessed impeccable protestant roots, unlike the First and Third Foot Guards with their strong Royalist, that is Stuart, High Church antecedents.

Coldstream Guards marching across Horse Guards Parade in 1750: picture by John Chapman: Death of General Edward Braddock on the Monongahela River on 9th July 1755 in the French and Indian War

On assuming the British throne in 1660, King James II gave Monk the title of the Duke of Albemarle. With the death of Monk and his son, the title became extinct and was available for King William to bestow as an earldom on van Keppel, the title having strong links with the Protestant tradition.

The Coldstream Guards, the only surviving New Model Army formation, was a regiment that could be relied upon to be free from Jacobite sympathies and enjoyed the particular confidence of the Duke of Cumberland and the King.

The Duke of Cumberland joined the Army as a major-general in 1742 and was immediately appointed colonel of the Coldstream Guards.

Lord Albemarle became one of Cumberland’s close associates. Albemarle was appointed colonel of the Third Troop of Horse Guards in 1743 and fought at the Battle of Dettingen, where both he and Cumberland were wounded. Dettingen was of great significance to the Hanoverian establishment as King George II was present at the battle. To have been wounded at this battle could be seen as a further gesture of loyalty to the Crown.

In 1744 Lord Albemarle was appointed colonel of the Coldstream Guards, an appointment he held until his death in Paris on 22nd December 1754. In 1745 Albemarle was again wounded, during Cumberland’s attack at the Battle of Fontenoy. Later in that year Albemarle commanded the first line at the Battle of Culloden, Cumberland’s iconic victory over Prince Charles Edward Stuart that ended the ’45 Rebellion.

From 1746 to 1747 Albemarle was commander-in-chief in Scotland supervising the suppression of the Jacobite clans.

In 1747 Lord Albemarle returned to Flanders with the Duke of Cumberland and held an infantry command in the rank of lieutenant-general at the Battle of Lauffeldt.

Lord Albemarle had been with Cumberland at every important episode in the Royal Duke’s military career between 1743 and 1748.

Lord Albemarle’s eldest son Lord Bury, also an officer in the Coldstream, was aide de camp to Cumberland during the ’45 and for the rest of King George’s War in Flanders, being present with the Duke at the Battle of Lauffeldt. In 1746 Lord Bury became colonel of the 20th Foot with James Wolfe as his lieutenant colonel.

Battle of Fontenoy on 11th May 1745; the British Foot Guards confront the Garde Française: picture by Edouard Detaille: Death of General Edward Braddock on the Monongahela River on 9th July 1755 in the French and Indian War

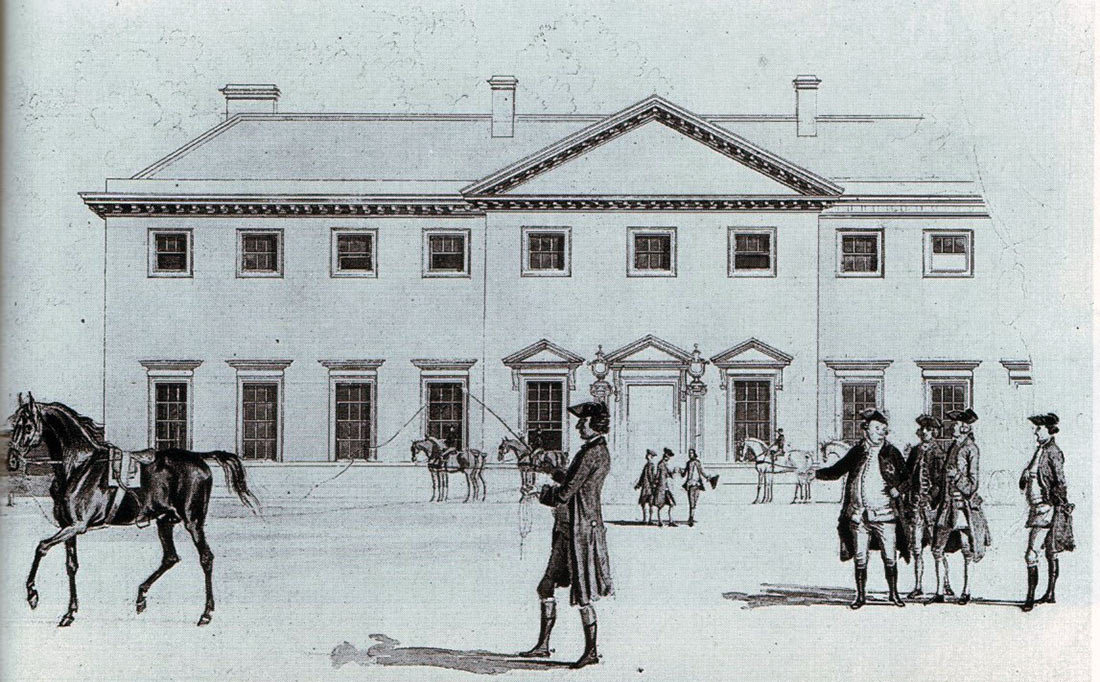

When Cumberland put forward his scheme for a viceroy in America in 1754, it was Lord Albemarle Cumberland proposed for the post. A contemporary print shows the Duke inspecting a horse in the course of his favourite past-time, breeding race horses. The Duke is shown accompanied by the Earl of Albemarle. Albemarle was one of the Duke’s longest standing and closest associates.

Print by Thomas Sandby, showing the Duke of Cumberland watching a horse being lunged. Cumberland has his right hand extended. Next to him are Sir Thomas Rich and the Earl of Albemarle. Sandby includes himself in the picture, standing on the extreme right.

In 1748, following the Treaty of Aix la Chapelle and at a very sensitive time, Albemarle was appointed the British Ambassador to France, thus confirming the trust the King also had in him.

Among the appointments Lord Albemarle received, he was in 1737 appointed Governor of Virginia. Albemarle never visited Virginia. His role was performed by his lieutenant governor of the time, who paid him a substantial annual fee for the appointment.

It can be surmised that Albemarle took an immediate interest in the continued financial security of his lieutenant governors, including Robert Dinwiddie, and in the pre-eminence of his colony, Virginia. When Virginia strove to influence British government policy, it had, in the Earl of Albemarle, a perfectly placed and powerful intermediary.

Albemarle’s letter book from his time in Paris states that he was in regular receipt of reports from his deputy-governor Robert Dinwiddie on affairs in Virginia.

Lord Albemarle was a spendthrift. Horce Walpole comments that Albemarle’s appointment in Paris was highly convenient in taking him beyond the reach of his creditors.

The previous section on Braddock’s defeat on the Monongahela in 1755 is Part 2: The deterioration in relations between Britain and France in America

The next section on Braddock’s defeat on the Monongahela in 1755 is Part 4: The appointment of Edward Braddock as commander-in-chief in America

To the French and Indian War index