The account of General Braddock’s expedition to Fort Duquesne in 1755 :

Part 1: The origins of General Braddock’s expedition.

French ‘voyageurs’ and Native Americans navigating a North American river by canoe: Death of General Edward Braddock on the Monongahela River on 9th July 1755 in the French and Indian War

Podcast Braddock’s Defeat Part 1: The account of General Braddock’s expedition to Fort Duquesne in 1755: The origins of General Braddock’s expedition: John Mackenzie’s britishbattles.com podcast

Podcast Braddock’s Defeat Part 1: The account of General Braddock’s expedition to Fort Duquesne in 1755: The origins of General Braddock’s expedition: John Mackenzie’s britishbattles.com podcast

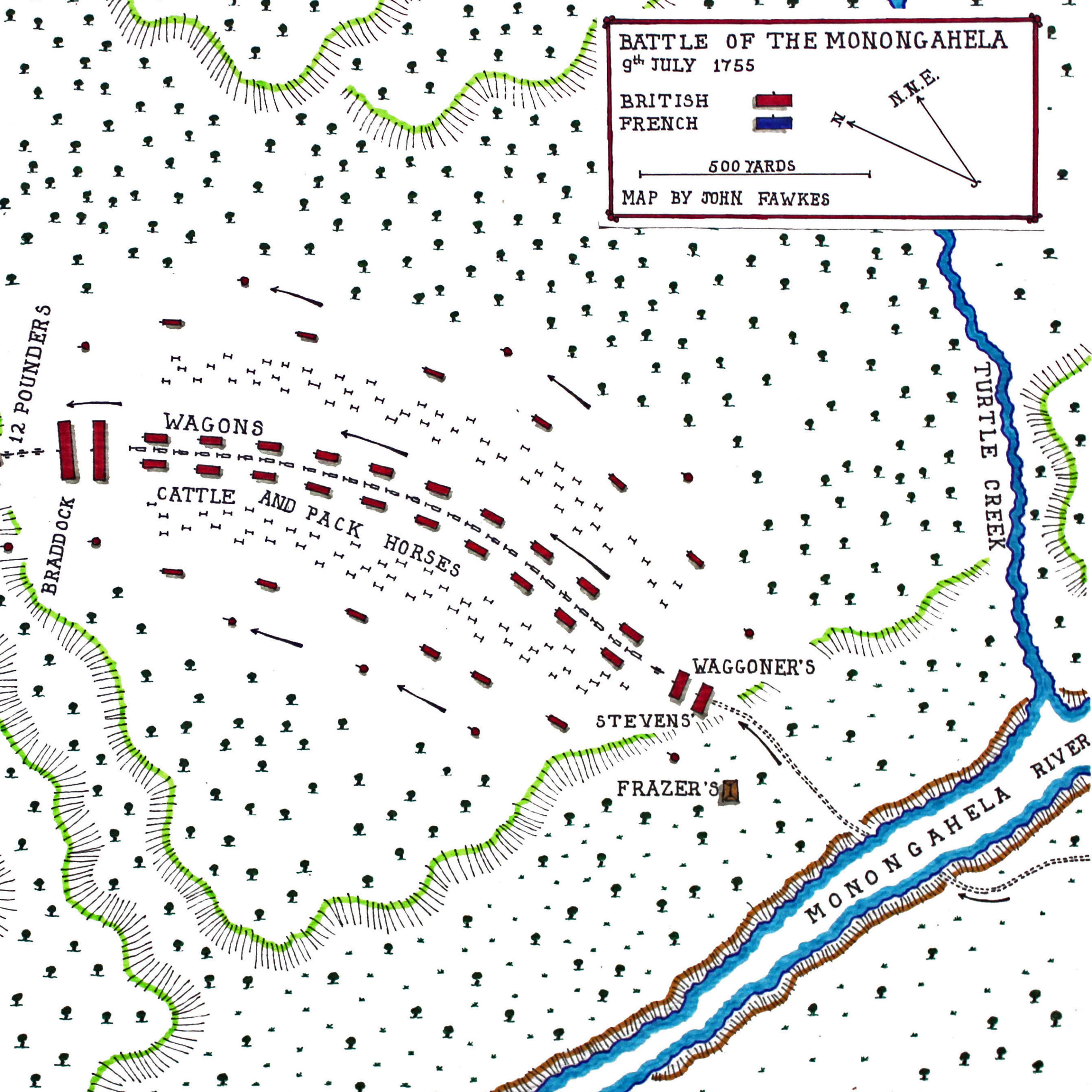

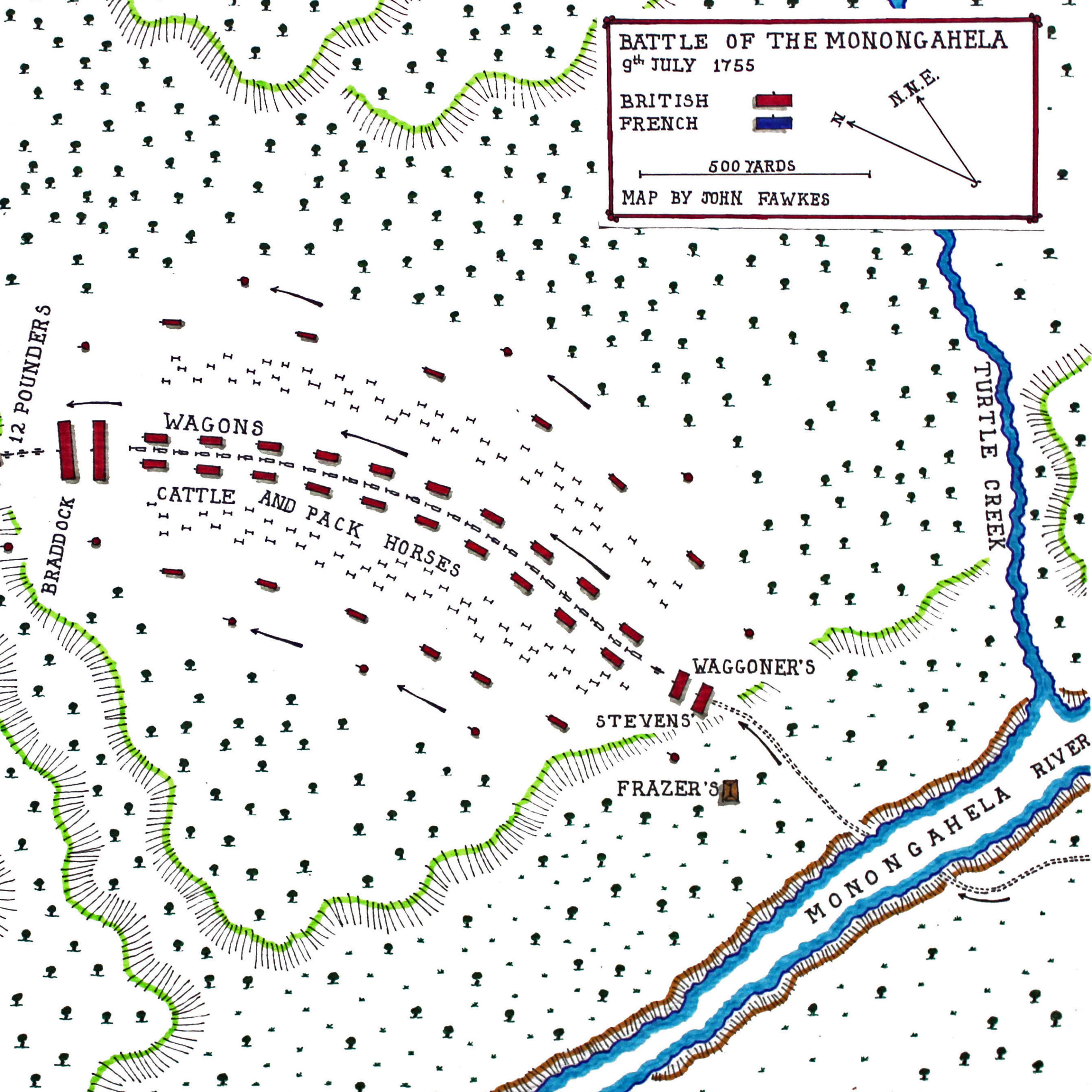

The previous Battle in the French and Indian War is the Battle of Monongahela 1755

The next section on Braddock’s defeat on the Monongahela in 1755 is Part 2: The deterioration in relations between Britain and France in America

To the French and Indian War index

Introduction:

In February 1755, the British officer Major-General Edward Braddock arrived in Virginia in North America with two British regiments of foot. Together with regular companies from New York and South Carolina and companies of Provincial troops from Virginia, North Carolina and Maryland, Braddock marched these regiments across the Allegheny Mountains, with the plan of capturing the French Fort Duquesne, situated at the Ohio Forks, where the Ohio, Allegheny and Monongahela Rivers meet and where Pittsburg now stands.

On 9th July 1755, this force met disaster; a disaster that had major implications for British rule in America and was a seed for the American Revolution in 1775.

Braddock’s expedition in 1755 provoked the outbreak of the French and Indian War, known in Europe as the Seven Years War. This war is aptly described as a World War, with fighting across Europe, North America, Central America, India and the Pacific.

The Treaty of Utrecht:

The back cloth to Braddock’s expedition was the hostility between the French and the British in North America that simmered throughout the first half of the 18th Century.

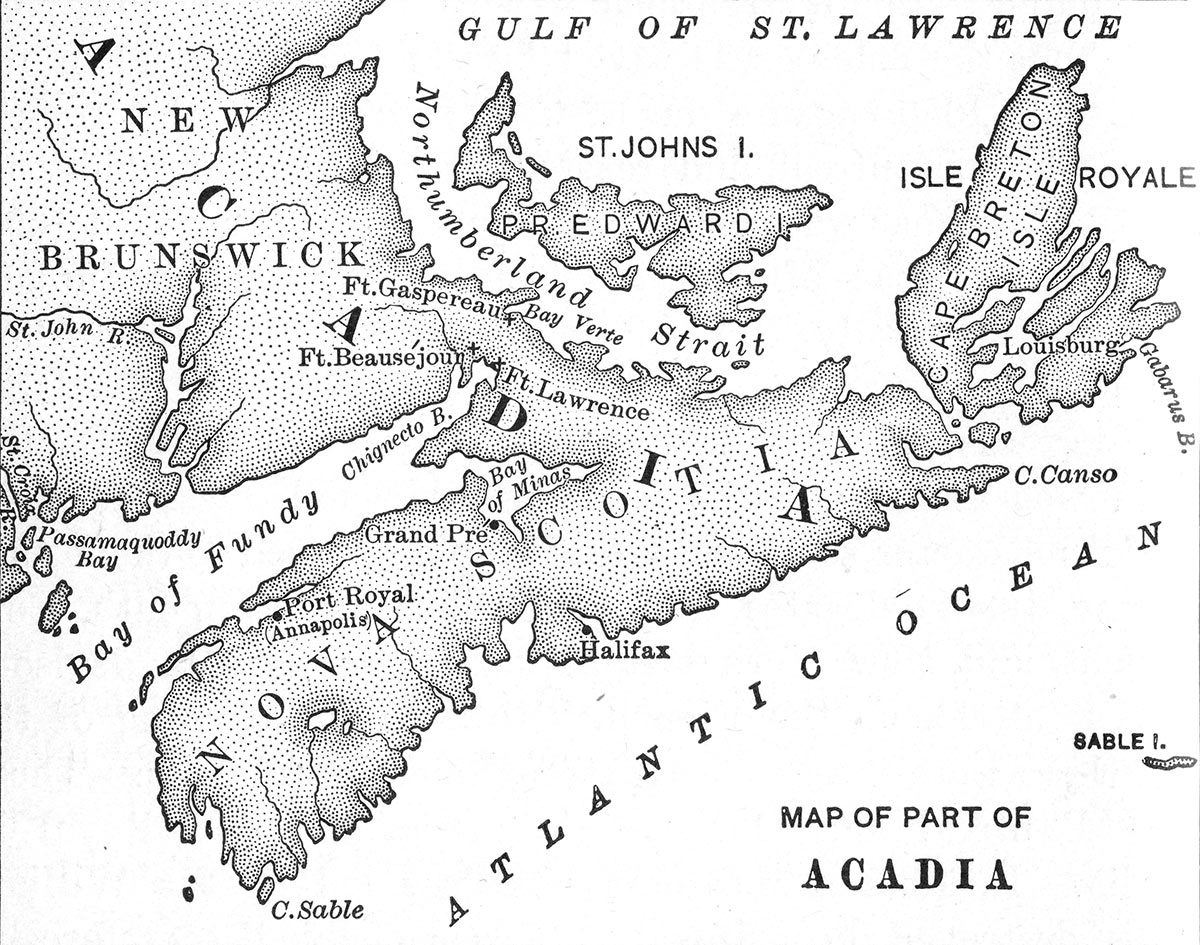

British-French relations in North America were addressed by the Treaty of Utrecht in 1713, the treaty that ended the War of the Spanish Succession in Europe. By the terms of that treaty France ceded a number of Canadian territories to Britain including Acadia (now Nova Scotia).

The French also made the concession, to prove of considerable importance as the British colonies expanded, that the Iroquois nations were to be treated as subjects of the British Crown.

No authoritative demarcation of the boundaries between Canada and the British American colonies followed the treaty. This lack of certainty on the physical extent of each country’s colonies was to be a simmering source of conflict between the French and British colonists for the rest of the half century.

King George’s War:

The Treaty of Utrecht initiated some 30 years of peace, finally ending with the outbreak in 1742 of the War of the Austrian Succession also known as the Silesian Wars.

In 1745 Prince Charles Edward Stuart, encouraged by the French, landed in Scotland and began his attempt to recover the throne of Britain for the House of Stuart, an attempt that ended with Prince Charles’s defeat at the Battle of Culloden on 16th April 1746

The war spilled into North America, where it was known as King George’s War. In 1746 New England colonists captured the French fortress of Louisburg on Cape Breton Island.

The Treaty of Aix la Chapelle:

In 1748 the exhausted European combatants signed the Treaty of Aix la Chapelle, ending the war. To the fury of the American colonists Cape Breton Island with the fortress of Louisburg was returned to France in exchange for French withdrawal from the areas of the Austrian Netherlands and the United Provinces (Holland) they had captured and guarantees on the Electorate of Hanover of which King George II was the Elector. The Americans were forced to learn, as the English had already learnt, that King George II put the interests of Hanover before all others.

For many in Britain, France and North America the Treaty of Aix La Chapelle was only a truce and the expectation was that the war would in due course be resumed.

By the Treaty, the French Crown renounced further support for the Stuarts in their struggle to recover the Crown of Great Britain. The ’45 Jacobite Rebellion had been a particularly dangerous episode for King George II and his government. Although the war was over, Prince Charles Edward Stuart continued to roam Europe seeking supporters for a renewed attempt to recover the British Throne. The perceived Jacobite threat continued to be an important undercurrent in British and American politics through the rest of the 1740s and 1750s.

The Boundary Commissioners in Paris:

In compliance with the terms of the Treaty of Aix la Chapelle, in 1748 commissioners for Britain and France met in Paris to try and agree the boundaries between French Canada and the British American Colonies. In the first two years of this vexed quest one of the British Commissioners was Governor Shirley of Massachusetts. It quickly became clear to Governor Shirley that the British and French could never agree on this issue.

Governor William Shirley of Massachusetts, a relation by marriage to the Duke of Newcastle. Shirley’s son acted as Braddock’s secretary and was killed on 9th July 1755: portrait by Thomas Hudson

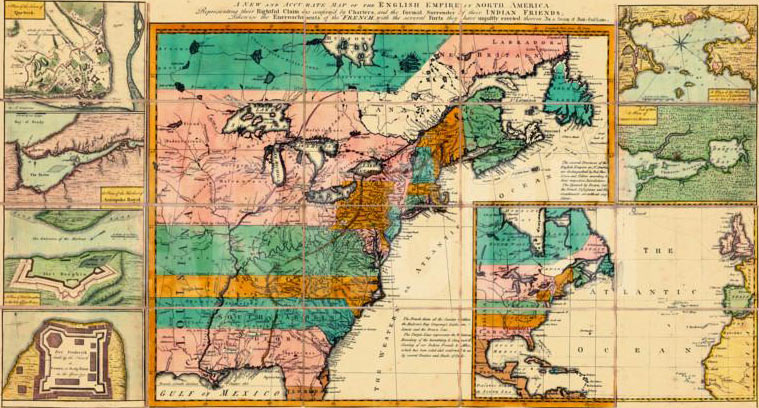

The colonies of each nation were not considered to be fixed entities and were expected to expand at the expense of the other nationality whenever the opportunity arose. A major obstacle to any form of agreement was that for many of the protagonists on each side the presence of the other nationality anywhere in North America was unacceptable.

This view was articulated by Colonel Thomas Lee, the prominent Virginian plantation owner and politician, when he wrote on 29th September 1750 to the Lords of Trade in London stating that “the French are intruders into this America.”

The French colonies in North America:

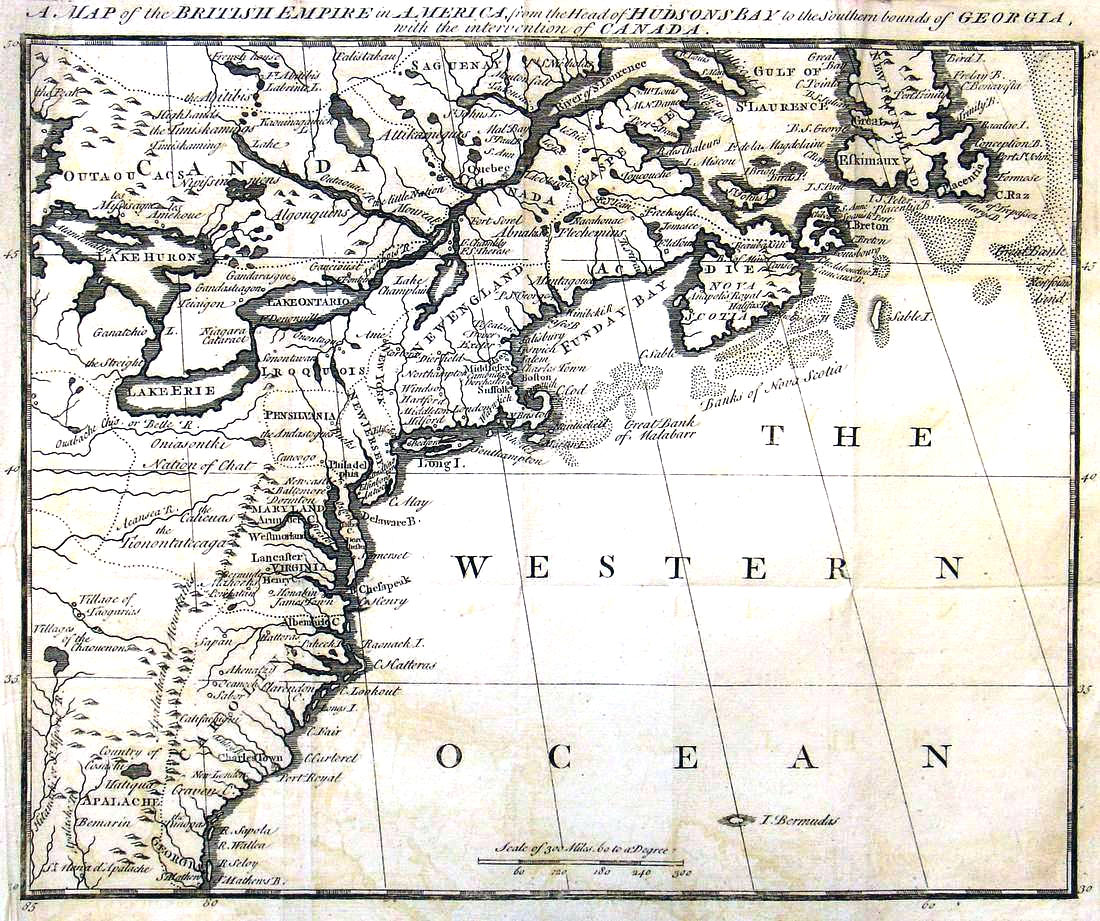

The main French North American colony of Canada stretched along the St Lawrence River from the Atlantic Ocean to Lake Erie. The British and American view was that the St Lawrence ought to be the boundary for Canada, with the French confined to the north bank of the river. However the French ‘habitants’ colonised both banks of the St Lawrence and edged southwards, encroaching on land considered by the British colonies to be part of New York or New Hampshire.

On the eastern seaboard, the border between Acadia, ceded by France to Britain under the Treaty of Utrecht and increasingly called Nova Scotia, and Canada remained ill-defined and an area of dispute.

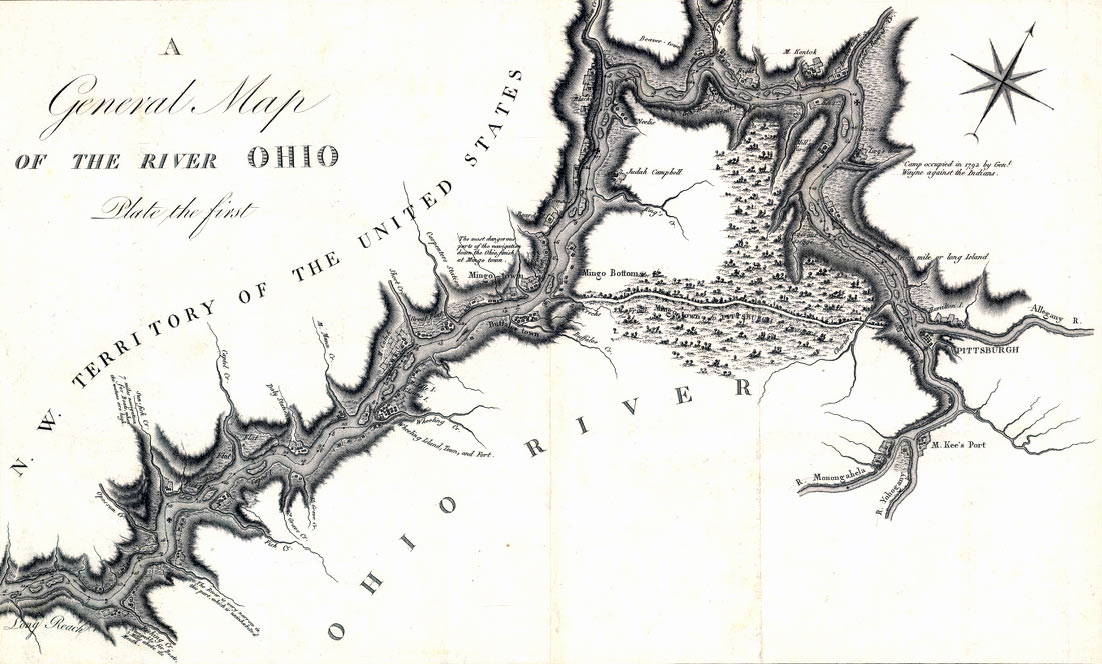

The French had colonised the area on the Gulf of Mexico that they called Louisiana. In order to improve communications between Louisiana and Canada the French sought to explore and establish posts up the Mississippi, Ohio and Allegheny Rivers. Such a line of communication would relieve Canada of the annual isolation caused by the winter icing up of the St Lawrence River.

All these matters were in dispute and potential points of conflict between Britain and France.

The French colony in Canada:

French Canada was a relatively homogenous colony. The non-native population was almost entirely French and its society replicated the authoritarian stratification of France: a governor representing the King, with a petty ‘gentilesse’ ruling the various areas, each with its population of ‘habitants’. The whole population had the same religion, Catholicism, and Catholic priests assisted in maintaining every aspect of the rigid social structure.

The British Colonies in North America:

British America was very different. The New England colonies were largely Puritan and English, enjoying a fractious relationship with the authority of the home country. New York contained a large German, Scandinavian and Dutch population among the Scots, Irish, Welsh and English. Pennsylvania was dominated by a Quaker establishment and populated by Scotch Irish, English and Germans.

Virginia was the largest and most populous British colony. Its establishment was dominated by owners of tobacco plantations who considered themselves to be English Squires and fostered close links with England. The religious establishment was strongly Anglican, although in the 1740s widely influenced by the preaching of the radical cleric, George Whitfield.

While the constitutional arrangements for the British American colonies differed in detail, they possessed a common feature in that each was regulated by an assembly of elected locals and a governor appointed by interests in England. A recurring theme was the antagonism between each assembly and its governor, particularly over financial matters.

Concerted action by the British colonies was difficult to achieve, while in Canada the French possessed the advantage of rule by a single royal governor of unquestioned authority.

Conflict between Britain and France in the 1750s:

It was in relation to Virginia that matters came to a head in the 1750s between Britain and France. The populations of the British colonies were growing faster than that of French Canada and there was constant pressure in each border colony to grow to the west. The colonies of Virginia and Pennsylvania coveted the expanse of forest in the area up to the junction of the Ohio, Allegheny and Monongahela Rivers, known as the Ohio Forks.

There was an underlying British assumption that the whole American continent on the same latitude as existing British colonies was owned by the British Crown. Two further concepts were relied upon in asserting that land to the west was British territory. The first was that where an area was explored by a Britain that area became British. The French employed the same argument in relation to French explorers. The second arose from the Iroquois concession in the Treaty of Utrecht. As many of the native Americans to the immediate west of the British colonies were either Iroquois or had been beaten in war by one of the Iroquois nations, they were said by the British authorities to be either Iroquois or vassals of the Iroquois and either way they were vassals of the British state and the land they lived on was British territory.

A major difficulty for the British was that where new land was claimed for Britain there was often then an argument as to which colony it belonged to and therefore which governor had the entitlement to make grants of that land. This problem arose in relation to the important Ohio Forks country, which was claimed by both Virginia and Pennsylvania.

Iroquois scalping a prisoner: Death of General Edward Braddock on the Monongahela River on 9th July 1755 in the French and Indian War

When considering the sequence of events in relation to this land and the morality of the conduct of the Virginian authorities it should be born in mind that the Ohio Forks country was an area a hundred miles or so beyond the western border of British inhabited Virginia and that most of Western Virginia could only be described as sparsely populated. Virginia had no need of the Ohio Forks country, other than as a source of speculative enrichment.

The Ohio Company of Virginia:

In the late 1740s a number of prominent Virginians joined in a property venture to be called the Ohio Company. They intended to apply for a substantial grant of land at the Ohio Forks. This was a speculative venture designed to enrich the members of the company by introducing settlers into the area and charging them for their new land. The Ohio Company was one of several such companies, but was the most important, including as its members men from some of Virginia’s most influential families; the Lees, Washingtons, Fairfaxes and Mercers (John and George).

Lawrence Washington, half brother of George Washington, and one of the founding members of the Ohio Company:

picture possibly by Hesselius

The Ohio Company’s petition for land at the Ohio Forks:

In 1747 the members of the Ohio Company submitted their petition to be granted 2,000 acres on the Ohio River to Sir William Gooch, the Lieutenant Governor of Virginia. Gooch was approaching the end of a long and placid governorship. Gooch was reluctant to grant the petition as he considered, correctly, that such a grant would inflame relations with the French. Gooch evaded making a decision and referred the petition to the Lords of Trade in London, the British Government body with responsibility for the American colonies.

The Ohio Company’s petition was vigorously supported before the Lords of Trade by John Hanbury, a London merchant whose business was to ship the tobacco of many of the Virginia plantation owners and provide them with goods imported from England. Hanbury was also a member of the Ohio Company.

At a meeting on 23rd February 1748, attended by John Hanbury, the Lords of Trade approved the petition from the members of the Ohio Company and referred it to the Privy Council for a definitive decision. In December 1748 the Privy Council endorsed the decision of the Lords of Trade to grant the Ohio Company petition for a grant of land at the Ohio Forks. On 16th February 1749 the Lords of Trade considered the petition at a further meeting attended by John Hanbury and on 16th March 1749 the Privy Council wrote to Governor Gooch directing him to make the grant and instructing him to add the stipulations that a fort be built at the Ohio Forks and that two hundred families be moved into the area.

Meeting of the Privy Council in 1774 (the occasion when Benjamin Franklin appeared before the Privy Council): picture by Christian Schussele

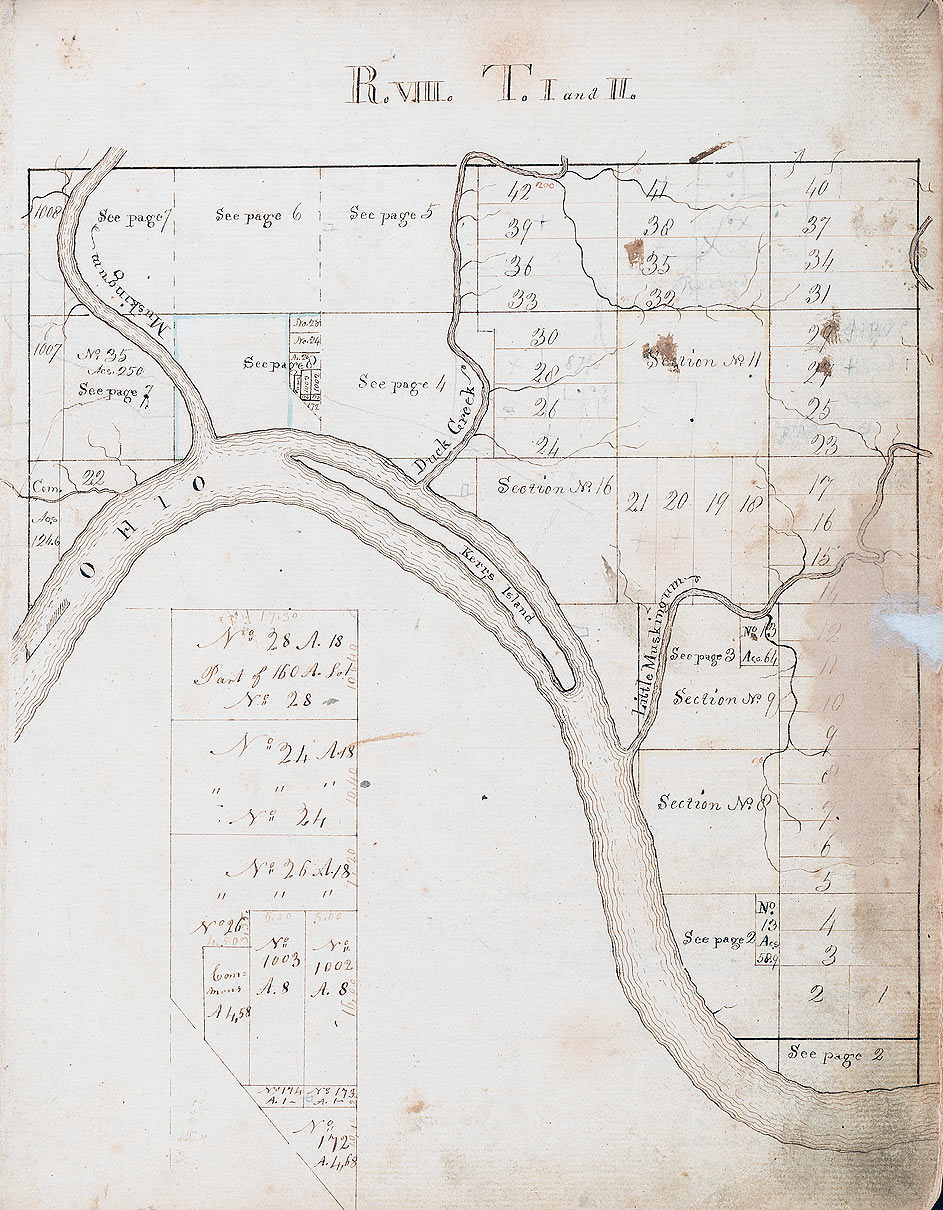

At some time in 1748 the Ohio Company bought from Lord Fairfax, the owner of a large tract of Virginia up to its western border, the land at Will’s Creek, the north west point of the Potomac River. Will’s Creek was the obvious place from which to establish a route to the Ohio country from Virginia.

Map of the Ohio River showing the junction with the Allegheny River where Fort Duquesne was built (marked as ‘Pittsburg’)

In 1749 the Ohio Company built a store house on the Virginia side of the river at Will’s Creek. The company ordered goods to trade with the Native Americans from John Hanbury in London to be delivered over the next three years.

The first Ohio Company expedition to the Ohio Forks:

In September 1749, secure in its grant from Governor Gooch, the Ohio Company sent its first exploration team under Barny Curran, Hugh Parker and Thomas Cresap to explore the Ohio country and investigate where colonists might be settled.

Virginian expansionist plans excited suspicion and hostility and not just from the French. Governor Hamilton of Pennsylvania was persuaded by the Pennsylvanian traders to launch an investigation into Virginian activity in the Ohio Country. The view in Pennsylvania was that if the Ohio Country was British it was part of Pennsylvania.

The end of Governor Gooch’s term of office:

In 1750 the prospects for the Ohio Company improved significantly when Governor Gooch’s term of office came to an end. The interim governor in his place became Colonel Thomas Lee as the chair of the Virginia House of Assembly. Thomas Lee was a prominent founding member of the Ohio Company. It was during this interim governorship that Thomas Lee wrote to the Lords of Trade saying that the French were intruders in America.

Thomas Lee’s sentiments struck a chord in London and his formal appointment to the post of Lieutenant Governor of Virginia was on the High Seas when on 12th February 1751 Lee died.

Christopher Gist’s first expedition for the Ohio Company:

The initial exploration of the Ohio Country was not a success and on 31st October 1750 Christopher Gist, an experienced frontiersman, left on a further more extensive investigation of the country along the Ohio River on behalf of the company. Gist ended his expedition at Roanoke on 17th May 1751. Gist described having to conceal his compass to prevent the Native Americans from realising that he was surveying the country for occupation by settlers.

Moves into the Ohio Country by the French:

The French also were suspicious of British incursion into the area. In 1750 the French officer La Jonquiére rounded up as many English Traders as he could find in the area of the Ohio Forks and sent them under arrest to Canada, many ending up in prison in Paris where they were finally released through the intervention of the British Ambassador, the Earl of Albemarle. Albemarle was an important player in this saga.

The French also began a ruthless campaign to eliminate Native American support for the British.

On 21st June 1751 La Jonquiére, with a force of Canadian Native Americans, attacked the Twightwee village of Pickawillamy on the Ohio River. Many villagers were killed. The chief known as Old Britain because of his pro-British sentiments (but also as Demoiselle) was killed and eaten by the raiders.

Christopher Gist’s second expedition for the Ohio Company:

On 4th November 1751, Christopher Gist set off on his second journey of investigation into the area of the Ohio River on behalf of the company. This second journey was more successful. Gist identified an area on the south bank of the Youghiogheny River for the Ohio Company’s first settlement, known as Gist’s Plantation. Settlers moved into ‘Gist’s Plantation’ for a time.

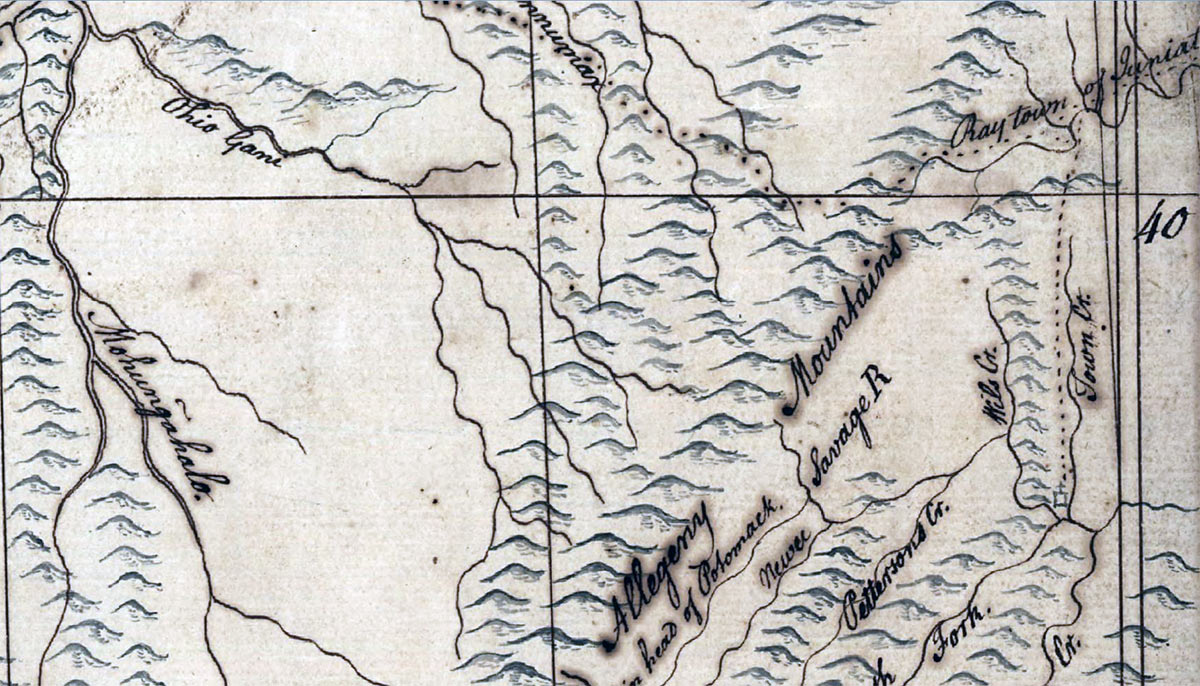

Gist travelled back by the path later known as ‘Nemacolin’s Trail’ and recognised it as the route the Ohio Company needed for the most direct access to the Ohio Forks from Will’s Creek. In reverse this would be the route taken by General Braddock’s ill-fated army in 1755. Gist arrived back at Will’s Creek on 29th March 1752.

Later in 1752, the Ohio Company engaged Thomas Cresap to build a road to the company’s land grant at the Ohio Forks along the route identified by Gist. Cresap engaged Nemacolin, a Delaware Native American, to help blaze the trail. Cresap, Gist and Nemacolin began the work on the road, but got no further than forcing a path along the route that was then known as ‘Nemacolin’s Trail’. In 1754, Trent, on his way to the Ohio Forks to build the fort, widened the path sufficiently to allow pack horses to pass.

Trader’s map showing the country between the Monongahela (on the left)

and Will’s Creek (on the right) crossed by Nemacolin’s Trail prior to 1753

The previous Battle in the French and Indian War is the Battle of Monongahela 1755

The next section on Braddock’s defeat on the Monongahela in 1755 is Part 2: The deterioration in relations between Britain and France in America

To the French and Indian War index

Podcast Braddock’s Defeat Part 1: The account of General Braddock’s expedition to Fort Duquesne in 1755: The origins of General Braddock’s expedition: John Mackenzie’s britishbattles.com podcast

Podcast Braddock’s Defeat Part 1: The account of General Braddock’s expedition to Fort Duquesne in 1755: The origins of General Braddock’s expedition: John Mackenzie’s britishbattles.com podcast