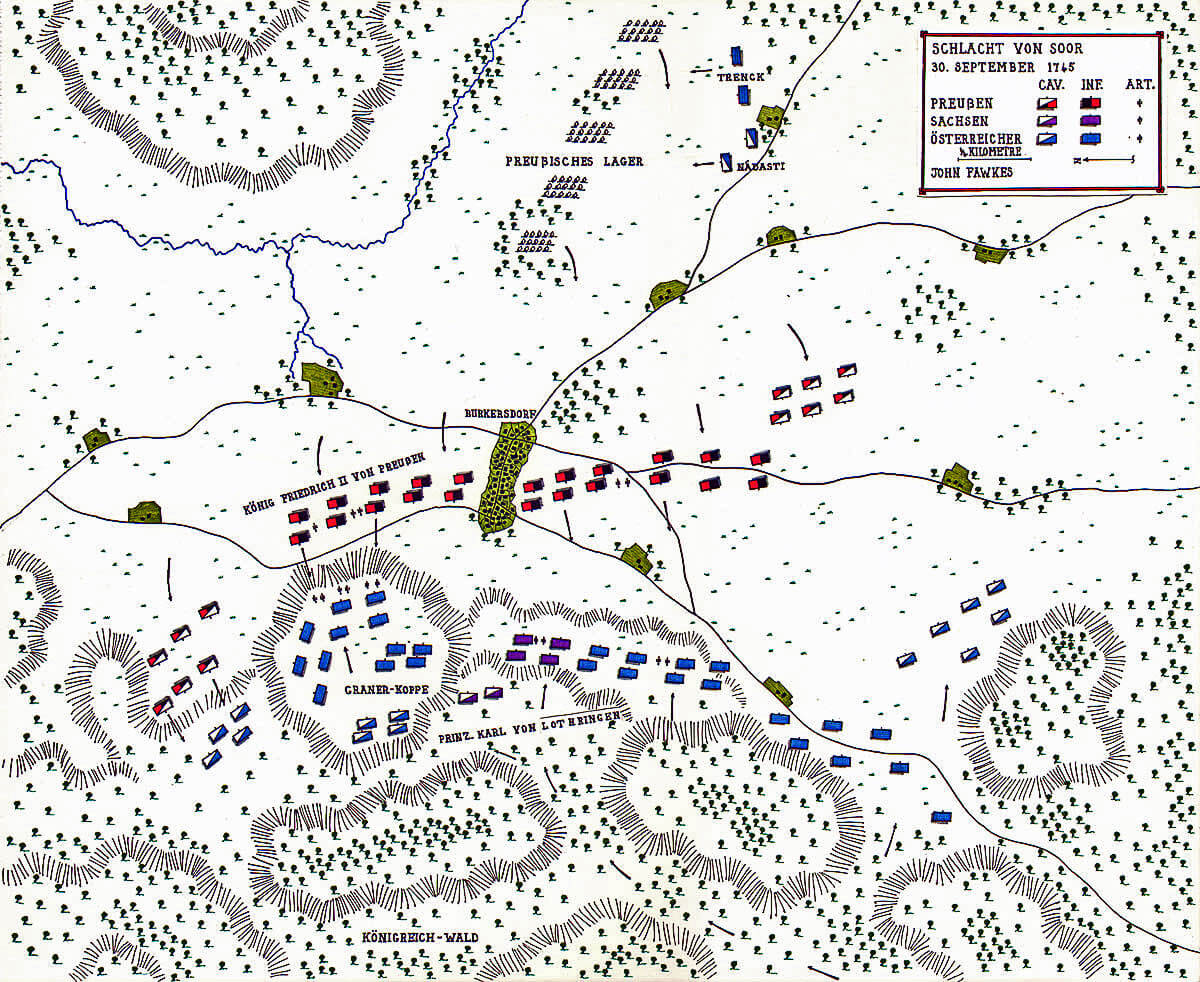

The victory, fought on 30th September 1745, that rescued Frederick the Great and his Prussian Army from ‘a fix’

General Nadasty’s Hungarian Hussars attacking the Prussian camp during the Battle of Soor 30th September 1745 in the Second Silesian War: picture by David Morier

The previous battle in the Second Silesian War is the Battle of Hohenfriedberg

The next battle in the Second Silesian War is the Battle of Kesselsdorf

To the Second Silesian War index

Battle: Soor

Date of the Battle of Soor: 30th September 1745.

Place of the Battle of Soor: In the North East corner of Bohemia near to the Silesian border.

War: The Second Silesian War.

Contestants at the Battle of Soor: Prussians against an army of Austrians and Saxons.

Generals at the Battle of Soor: King Frederick II of Prussia commanding the Prussian Army against Prince Charles of Lorraine, the brother of the Empress Maria Theresa, commanding the Austrian and Saxon Army.

Size of the Armies at the the Battle of Soor: 22,500 Prussians (16,700 infantry and 5,800 cavalry) against 40,200 Austrians and Saxons (23,500 infantry, 12,700 cavalry, and 4,000 irregular troops).

Winner of the Battle of Soor: The Prussians.

Prussian Grenadiers of the Guard in action at the Battle of Soor 30th September 1745 in the Second Silesian War

Uniforms and equipment at the Battle of Soor: The Prussian infantry and artillery wore a dark blue coat turned back at the lapels, cuffs and skirts, britches and white thigh length gaiters. From cross belts hung an ammunition pouch, bayonet and ‘hanger’ or small sword. Headgear for the line companies was the tricorne hat with the receding front corner bound with white lace. Grenadiers wore the distinctive mitre cap with the brass plate at the front. Fusilier Infantry Regiments and gunners wore the smaller version of the grenadier cap.

The infantry carried the musket as their main weapon. The single shot musket could be loaded and fired by a well trained soldier between 3 and 4 times a minute. During the course of his wars Frederick introduced the iron ramrod and then the reversible ramrod which increased the efficiency of his infantry, the wooden ramrod being liable to break in the stress of battle.

The Prussian infantry regiment was based on the cantonment, with soldier joining their local regiment. Soldiers were released for key agricultural times such as sewing and harvesting. In the autumn reviews were conducted of all regiments to check that each regiment was up to the required standard. Each year certain regiments were selected to conduct the review at Potsdam under the eye of the King. Officers whose soldiers were considered by Frederick not to be of a sufficient standard were subjected to a public tongue lashing and in extreme cases dismissed on the spot.

Prussian Kürassier-Regiment von Gessler No 4: Battle of Soor 30th September 1745 in the Second Silesian War: picture by Adolph Menzel

The efficiency of the Prussian regiments at drill enabled them to move around the battlefield with a speed and manoeuvrability that no other European Army could equal.

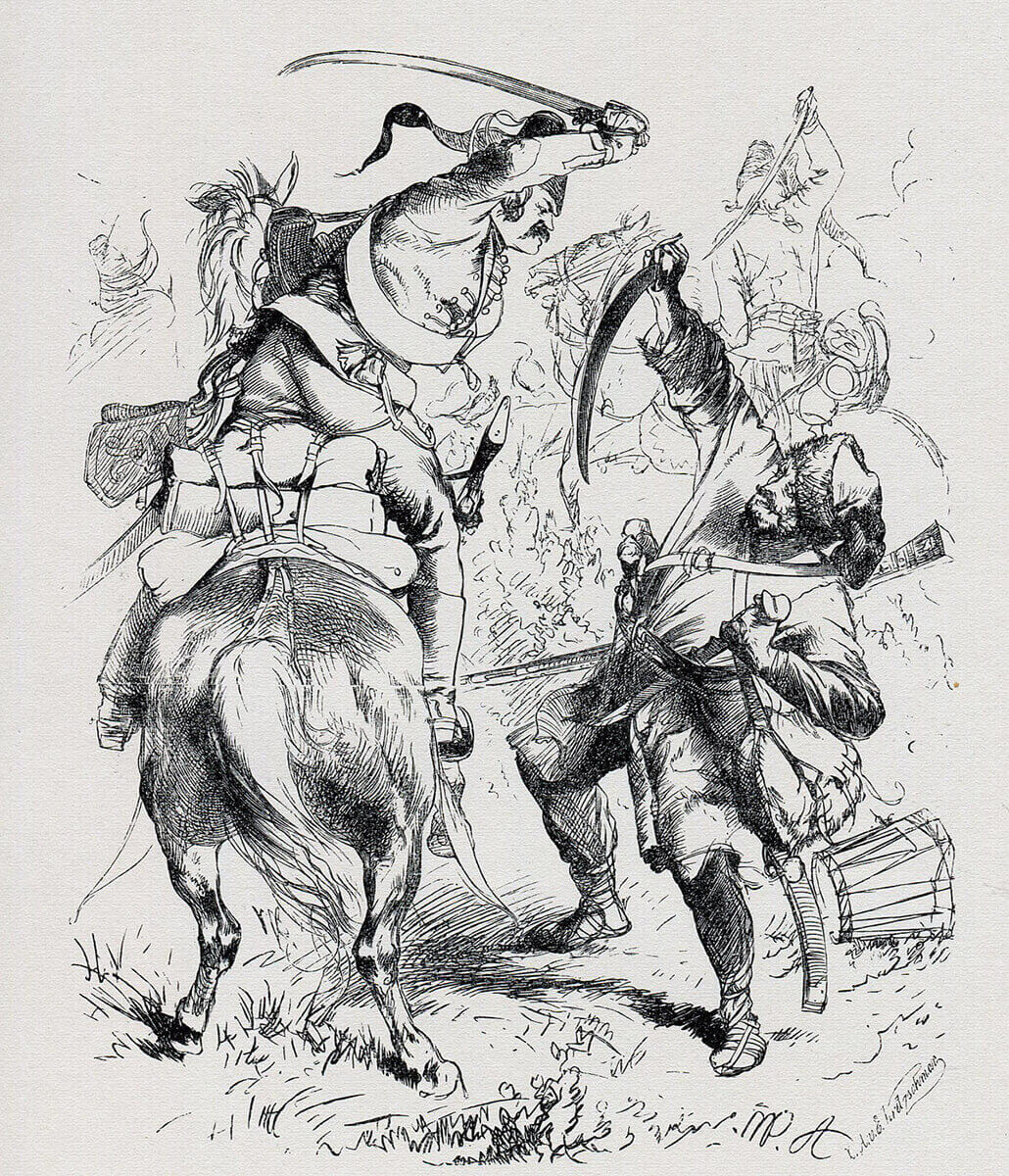

Heavy cavalry of the period comprised cuirassiers, whose troopers wore steel breastplates, and dragoons. The main form of light cavalry were the regiments of hussars. The Austrian hussars were Hungarian and the genuine article while the hussars of other armies were given the same dress as Hungarian hussars and expected to perform to similar standards.

The Prussian cuirassiers wore a white coat, steel cuirass, white britches and thigh boots. The headgear was the tricorne hat. Dragoons wore a light blue coat.

Weapons were a heavy cavalry sword and single shot flintlock carbine.

The light cavalry arm was provided by the Prussian Hussar regiments. Frederick found the Prussian Hussars as inadequate for their role as the heavy cavalry regiments. Following Mollwitz and in particular after the First Silesian War the hussars were re-organised and re-trained to provide a first class scouting and light cavalry service. Frederick found in Colonel von Zieten the ideal officer to implement the improvements in the hussar regiments.

The Prussian Hussars wore the traditional hussar dress worn by the original Hungarian Hussars of tunic, britches, dolman (slung jacket), busby (fur hat) with bag, sabretache (leather wallet on straps) and curved sword.

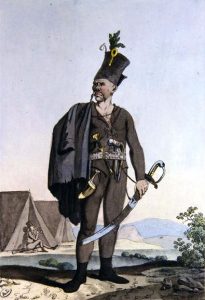

The Austrian infantry wore white coats with lapels, cuffs and skirts turned back showing the regimental lining colour. Headgear was the tricorne hat for line infantry and bearskin cap for grenadiers. The infantry weapons were musket, bayonet and hanger small sword. Heavy cavalry wore white coats and hats as for the infantry and were armed with a heavy sword and carbine. The Austrian army contained a large number of irregular units such as the Pandours from the Balkans who wore their ethnic dress without uniformity. Hungarian Hussars provided the light cavalry arm. These Hussars were dressed as described for the Prussian Hussars, were considered to be little more than bandits but were highly effective in all the roles required of light cavalry.

Banalist and Pandour from the Corps of Colonel Trenck: Battle of Soor 30th September 1745 in the Second Silesian War: Picture by David Morier

The artillery of each army was equipped with a range of muzzle loading guns. The Prussian Artillery was considerably more efficient at manoeuvring on the battle field. In the changes implemented by Frederick after the First Silesian War horse artillery was introduced to support the Prussian cavalry.

Prussian Infantry Regiment von Kalnein No 4: Battle of Soor 30th September 1745 in the Second Silesian War: picture by Adolph Menzel

The Battle of Soor Background

The Prussian Army and State of the middle of the 18th Century owed its strength to the father of Frederick the Great, King Frederick William, the ‘Soldier King’. The Kingdom of Prussia comprised a number of areas scattered across Northern Germany from Minden and the tiny provinces of Jules and Berg in the West to the more compact provinces of Pomerania and East Prussia on the Baltic coast in the East. The capital of Prussia lay in the City of Berlin in the heartland of Brandenburg. During his reign Frederick William established an efficient civil state with the primary duty of supporting a large and well organised army, the bedrock of which was the Prussian Infantry. The noble families of Prussia were required to commit their sons to the army’s officer corps. Unlike the military nobility in other European states the Prussian Officer Corps was expected to devote its energies to learning its fighting trade. Regiments were reviewed on an annual basis by the King and woe betide the officers of any regiment that fell below the required standard of drill and performance.

The Prussian Army established the technique of battlefield drill in the era of the musket. Prussian Infantry regiments could be trusted to move around the battlefield in order and at speed in a way that no other army could.

Prussian Husaren-Regiment von Puttkamer No 4: Battle of Soor 30th September 1745 in the Second Silesian War: picture by Adolph Menzel

Frederick the Great, while undoubtedly owing a great deal to the work his father had carried out on the army and state, brought his own unique talents to bear in improving the infantry and forging formidable assets out of the arms his father had neglected; principally the cavalry and the artillery, after the dismal performance of the Prussian cavalry at Mollwitz.

Frederick William had a reverence for the established order in Europe, holding the Emperor of Austria in particular awe. He would not have dreamt of launching Prussia on the extraordinary series of wars Frederick the Great began in 1741 by invading the Austrian province of Silesia.

Frederick William died on 31st May 1740 and Frederick II took the throne of the Kingdom of Prussia. On 20th October 1740 the Emperor Charles VI of Austria died leaving the imperial throne to his daughter Maria Theresa. Frederick resolved to seize the Austrian province of Silesia for Prussia.

Prosperous and partly Protestant, Silesia lay on the southern Prussian border along the banks of the river Oder. With its population of 1.5 million Frederick saw Silesia as a significant addition to the Prussian state with its 2.2 million inhabitants. But Frederick would have to fight 3 wars over 22 years with the Austro-Hungarian Empire for his prize.

In the First Silesian War (1740 to 1742) Frederick the Great fought the successful battles of Mollwitz and Chotusitz before negotiating the Treaty of Breslau in 1742.

In 1744 Frederick re-entered the war by invading Bohemia. After a disappointing campaign which saw the Prussian Army forced to retreat into Silesia, Frederick lured Prince Charles of Lorraine’s Austro-Saxon Army out of the hills and beat it in the iconic victory of Hohenfriedburg.

In the follow up to Hohenfriedburg Frederick again invaded Bohemia. September 1745 saw the Prussian Army retreating and encamped near the Bohemian village of Burkersdorf on the edge of the extensive Königreich-Wald (Forest) near to the Silesian border. Frederick planned to return to Berlin for the winter to inspect the building work on his new palace of Sans Souci as he reflected in wistful letters to his valet, Fredersdorf. The Austrians had other ideas.

The Battle of Soor Account

During the course of 29th September 1745 Prince Charles led his troops through the wooded hills of the Königreich-Wald around the flank of the Prussian camp. In the misty early hours of 30th September 1745 the Austrian and Saxon regiments took post on the hills overlooking Burkersdorf and the Prussians encamped beyond the village.

In the valley Prussian piquets hurried to report the presence of the Austrians to Frederick who, at 5am, was holding an early morning meeting with his generals. Frederick mounted and hurried along the Prussian lines to investigate the alarming report. In each regiment the drummers and trumpets beat and sounded the general alarm. The infantry fell in and the cavalry mounted. The Marquis de Valori, the French Envoy, was yet again struck by the initiative with which each regiment prepared itself for battle without specific orders.

With the lifting of the mist the Austrian guns on the Graner-Koppe, overlooking Burkersdorf, opened fire on the Prussian camp and the regiments now marching to engage them.

Frederick quickly formed his plan: a cavalry force would circle to the right of the Graner-Koppe and attack up the valley to the side of the hill encircling the Austrians and Saxons on the summit. As soon as possible an infantry assault would be launched on the summit of the Graner-Koppe. The remainder of the army would confront but not attack the Austrians and Saxons spread along the hill line to the South of Burkersdorf.

The Prussian cavalry heading to the valley had to pass the Graner-Koppe and submit to the bombardment from the Austrian guns on the summit. The regiments suffered significant casualties but pressed on. Clear of the fire of the guns the cavalry turned to the left and began the attack. The leading regiments of the Gens D’Armes and Buddenbrock’s Cuirassiers headed up the valley, scaling the steep end incline at the gallop, and engaging the surprised and stationery Austrian cavalry regiments at its top. The Austrians were put to flight. Encountering the fire of the Austrian infantry the Prussian regiments wheeled and fell on the rear of the force on the brow of the Graner-Koppe, closely supported by the Garde du Corps and the additional Prussian cavalry regiments that were coming up behind.

Prussian Hussar tackling a Pandour: Battle of Soor 30th September 1745 in the Second Silesian War: print by Adolf Menzel

In the meantime Prussian grenadiers and the Anhalt regiment, trained by the ‘Old Dessauer’ (Prinz Moritz of Anhalt-Dessau) himself, climbed the front of the Graner-Koppe and attacked the Austrian force established on the summit. In the face of heavy artillery fire and a strong infantry counter-attack the Prussian battalions were thrown back with substantial casualties. A second attack was launched comprising the Geist Grenadiers, the regiments of Blanckensee and La Motte and other veteran Prussian regiments. The confusion brought about by the first attack caused the Austrian batteries to be masked by their own infantry enabling the Prussian assault to be pressed home. The Austrians were driven from the summit.

The Prussian regiments holding the area south of Burkersdorf were directed to keep out of the fighting and provide a reserve for the Prussian assault on the Graner-Koppe, by their presence ‘fixing’ the Austrian right wing and preventing it from supporting the regiments of the Austrian left. This direction was ignored. A Prussian assault developed on Burkersdorf. A savage bayonet attack by the Prussian Guard led by Prince Ferdinand of Brunswick captured an Austrian battery and led to a general assault. The Austrian line collapsed and retreated in confusion. The Austrian cavalry of the right wing failed to support their colleagues and many of the infantry were captured by the cavalry regiments of the Prussian left wing.

By midday the battle was over and the Austrians and Saxons were melting away into the Königreich-Wald.

Prussian Infantry Regiment von Kalckstein No 25: Battle of Soor 30th September 1745 in the Second Silesian War: picture by Adolph Menzel

This time, unlike Hohenfriedburg, Frederick attempted to launch a pursuit. But his troops were having none of it. So far as they were concerned they had snatched a remarkable victory from potential disaster. They roared “Vivat Victoria” and took no notice of Frederick’s cries of “Marsch”.

Casualties at the Battle of Soor: The Prussians suffered casualties of 856 dead and 3,055 wounded and missing. The Austrians and Saxons suffered 7,444 dead, wounded and missing. Among the Prussian officers killed was Prince Albrecht of Brunswick, the brother of the Queen of Prussia.

Aftermath to the Battle of Soor: Frederick’s army remained on the field of battle for 5 days to emphasise that the battle had been a Prussian victory and then withdrew into Silesia. In November 1745 Austrian resilience showed itself yet again as Prince Charles resumed the offensive with an invasion into Saxony heading for Brandenburg. In a campaign lasting less than a week Frederick outmanoeuvred the Austrians and brought this incursion to a halt, forcing Prince Charles’ army back into Bohemia.

Anecdotes from the Battle of Soor:

- The Austrian grenadiers repelled the first attack on the Graner-Koppe with the war cry “Es lebe Maria Theresa”.

- King Frederick said of the battle in a letter to Fredersdorf “I have never been in such a fix as at Soor. I was in the soup up to my ears.” To the French ambassador le Marquis de Valori Frederick said “At Hohenfriedburg I was fighting for Silesia. At Soor I was fighting for my life.”

- As at Hohenfriedburg the quality of the Prussian Army clearly showed itself. The Army was strategically surprised by the Austrian/Saxon advance to the hills above Burkersdorf, but swiftly formed up and delivered a devastating counter-attack. The cavalry performed admirably in the charge uphill against the Austrians. The infantry’s attack on the Graner-Koppe led Frederick to form the view that Prussian infantry was irresistible even in a frontal assault against artillery and infantry of high quality and in superior numbers.

- During the battle Frederick’s personal baggage was captured by Austrian Hussars, including his beloved whippet ‘Biche’ and his flutes. Biche was returned under the terms of the final treaty at the end of the war. Frederick directed the Berlin flute maker Quantz to provide replacement instruments but “with a powerful sound, easy to blow and with soft high notes.”

- Nadasti and Trenck at Soor: The Hungarian hussar commander General Nadasti led his hussars around the rear of the Prussian Army while the Battle of Soor raged and ransacked the Prussian camp. The hussars were assisted by the irregular Croat infantry known as the Pandours commanded by Colonel Baron Franciscus von der Trenck. Among the booty seized by Trenck was the Prussian War Chest of 80,000 ducats. With the valuables of most of the Prussian Army and its king the loot taken during the sack of the Prussian camp was said to be worth 1,000,000 ducats; including Frederick’s dinner service, his flutes and, of course, his dog Biche.

- Trenck was a highly controversial officer of the Austrian Army. After service in the Russian Army in the 1730s Trenck conducted a vicious personal war against the Croat bandits who raided across the Turkish border into Hungary. On the outbreak of the First Silesian War Trenck raised a body of these same bandits and his own tenants to serve in Maria Theresa’s army against the Prussians, as the notorious Pandours. The Pandours robbed and fought their way across Bohemia, Silesia, Saxony and the Netherlands, while their commander accumulated fabulous wealth and a reputation for brilliant soldiering and appalling atrocities. Following the end of the First Silesian War in 1745 Trenck was arrested in Vienna and tried on a number of charges, including one that he was personally responsible for the Austrian defeat at Soor because he had spent the battle looting the Prussian camp instead of attacking the rear of the Prussian Army. This charge was further embellished until the accusation was that Trenck had found the Prussian King in bed with a young woman when the camp was stormed and that Trenck had accepted a bribe of a million ducats to permit Frederick to escape. Frederick must have read of the details of this extraordinary trial, which had Vienna in a state of turmoil for some weeks, with considerable amusement. Trenck was convicted and about to be executed when the proceedings were quashed by the Empress. However Trenck was, somewhat obscurely, convicted of causing the death of a civilian in Silesia and ordered to be confined for life in the fortress of Spielberg at Brunn. Trenck died in prison in further odd circumstances which gave rise to the suggestion that he should be canonised. Another strange member of the Trenck clan was ‘Prussian’ Trenck. Prussian Trenck was an officer in Frederick’s Foot Guards. He came under suspicion for his correspondence with his Austrian cousin and was cashiered from the Prussian Army. Prussian Trenck inherited Pandour Trenck’s estate on his death but found that his considerable wealth had melted away over the years leaving some 60 law suits to be dealt with. Prussian Trenck was guillotined by Robespierre as an Austrian spy after the French Revolution

References:

- Frederick the Great by Thomas Carlyle

- Frederick the Great by Christopher Duffy

- The Army of Frederick the Great by Christopher Duffy

- The Army of Maria Theresa by Christopher Duffy

The previous battle in the Second Silesian War is the Battle of Hohenfriedberg

The next battle in the Second Silesian War is the Battle of Kesselsdorf

To the Second Silesian War index