Frederick the Great’s first battle of the Seven Years War

against the Austrians: an unsatisfactory victory

Austrian and Prussian cuirassiers at the Battle of Lobositz on 1st October 1756 in the Seven Years War

The previous battle in the Seven Years War is the Battle of Kesselsdorf

The next battle in the Seven Years War is the Battle of Prague

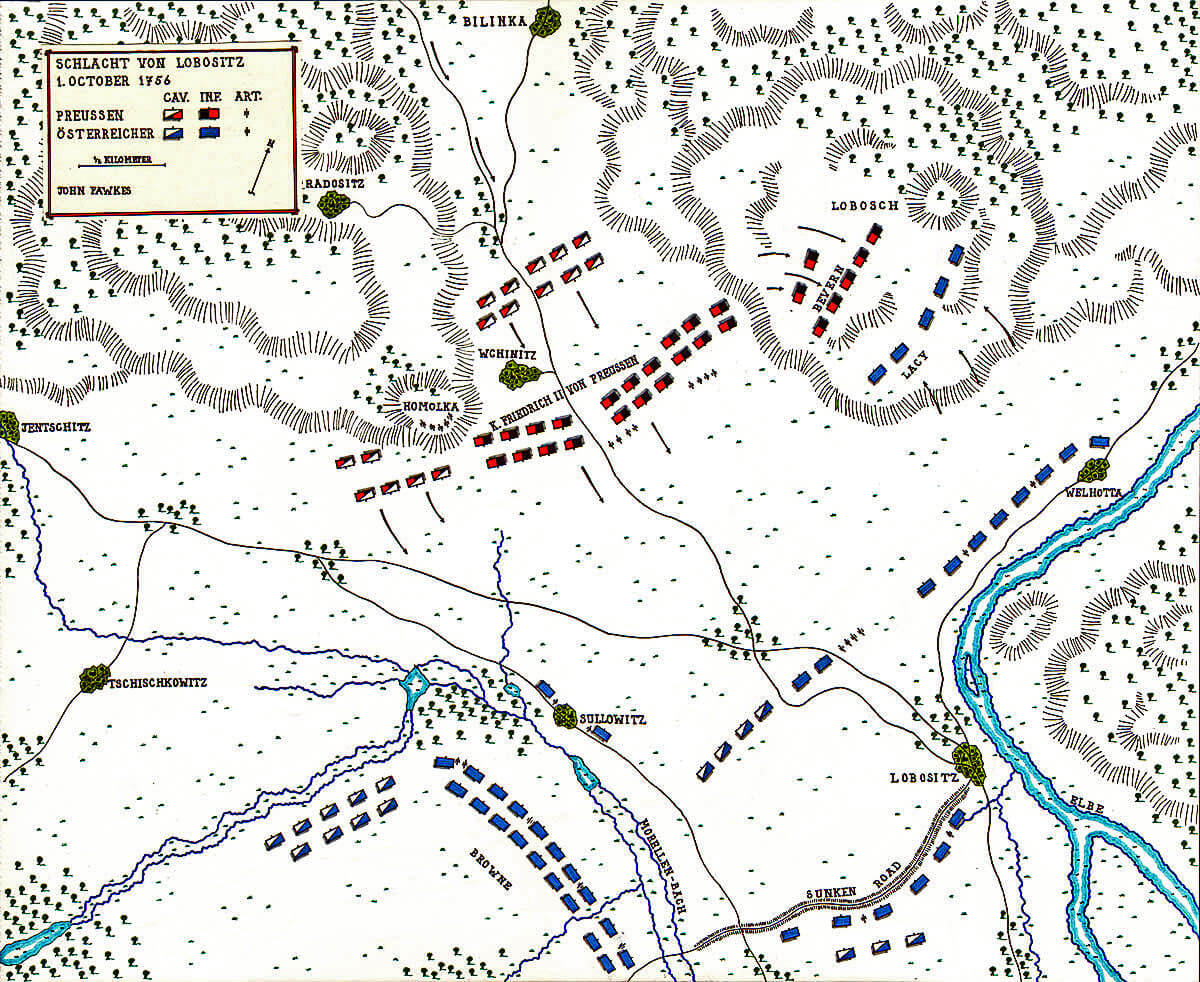

Battle: Lobositz

Date of the Battle of Lobositz: 1st October 1756.

Place of the Battle of Lobositz: In the North of Bohemia

War: The Seven Years War.

Contestants at the Battle of Lobositz: Prussians against an Imperial Austrian Army comprising the various nationalities that made up the Austrian-Hungarian Empire (Austrians, Hungarians, Bohemians, Netherlanders, Silesians, Croats, Italians and Moravians).

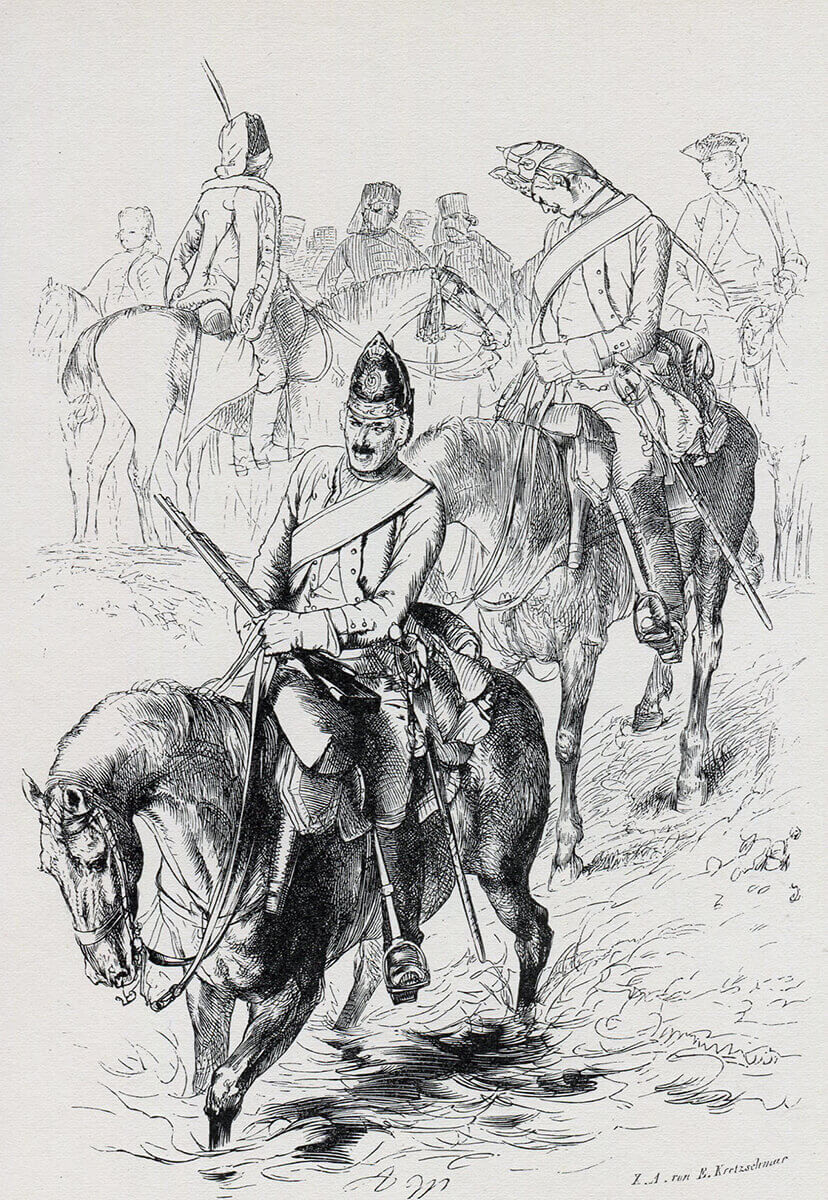

Prussian hussars and dragoon grenadiers: Battle of Lobositz on 1st October 1756 in the Seven Years War: picture by Adolph Menzel

Generals at the Battle of Lobositz: King Frederick II of Prussia commanded the Prussian Army against Field Marshal Browne commanded the Austrian Army.

Size of the Armies at the Battle of Lobositz: 31,800 Prussians (21,000 infantry, 10,800 cavalry) and 97 guns (plus light regimental pieces) against 34,000 Austrians (26,500 infantry, 7,500 cavalry) and 74 guns (plus light regimental pieces).

Winner of the Battle of Lobositz: The Prussians under Frederick the Great, but not decisively.

Uniforms and equipment at the Battle of Lobositz: The Prussian infantry and artillery wore a dark blue coat turned back at the lapels cuffs and skirts, britches and black thigh length gaiters. From a cross belt hung an ammunition pouch bayonet and ‘hanger’ or small sword. Headgear for the line companies was the tricorne hat, with a flattened front corner, bound with white lace. Grenadiers wore the distinctive mitre cap with a brass plate at the front. Fusilier Infantry Regiments and Artillery wore a smaller version of the grenadier cap with a brass grenade on the top.

Prussian Kürassier-Regiment von

Driesen No 7: Battle of Lobositz on 1st October 1756 in the Seven Years War: picture by Adolph

Menzel

The infantry carried a musket as the main weapon. This single shot firearm could be loaded and fired by a well trained soldier around 3 to 4 times a minute. As an early improvement Frederick introduced the iron ramrod and then the reversible ramrod (the soldier did not have to worry whether he had the ramrod the right way round) which increased the rate of fire of his infantry, the old wooden ramrod being liable to break in the stress of battle.

The Prussian infantry regiment was based on the cantonment with soldiers joining their local regiment. In peacetime soldiers were released for key agricultural times, sowing and harvesting. In the autumn, reviews were conducted of all regiments to check they were up to the required standard. Each year regiments were selected to undergo review at Potsdam under the eye of the King. Officers whose soldiers’ performance was considered by Frederick to be substandard were subject to a public tongue lashing and in extreme cases dismissal on the spot.

The efficiency of the Prussian regiments at drill enabled them to move about the battlefield with a speed and manoeuvrability that no other European Army could equal. The Battle of Rossbach is a striking example of this facility.

Heavy cavalry of the period comprised cuirassiers, whose troopers wore steel breastplates and dragoons. The main form of light cavalry was regiments of hussars. The true hussars were Hungarians in the Austrian service. The hussars of other armies were given the same dress as the original hussars and required to perform a similar light cavalry role of reconnaissance and harassing the enemy’s outposts and supply columns.

The Prussian cuirassiers wore a white coat, steel cuirass, white britches and thigh boots. Dragoons wore a light blue coat. The headgear was a tricorne hat. Weapons were a heavy cavalry sword and single shot flintlock carbine.

The light cavalry arm was provided by the Prussian Hussar regiments. Following the Battle of Mollwitz and in particular after the First Silesian War the hussars were re-organised and re-trained to provide an efficient scouting and light cavalry service. Frederick found in Colonel von Zieten the ideal officer to implement the improvements in the hussar regiments. The Prussian Hussars wore the traditional hussar dress of tunic, britches, dolman (slung jacket), busby (fur hat) with bag, sabretache (leather wallet on straps hanging from the belt) and curved sword.

Unlike the original Hungarian Hussars of the time who were considered little more than indisciplined freebooters the Prussian Hussars were well able to take a position in the cavalry line and perform valuable service in battle, as at the Battle of Hohenfriedburg and on other occasions.

Grenadiers of the Austrian infantry regiments ‘Los Rios’, ‘Waldeck’ and ‘Wurmbrand’: Battle of Lobositz on 1st October 1756 in the Seven Years War: picture by David Morier

The Austrian infantry wore white coats with lapels, cuffs and skirts turned back showing the regimental lining colour. Headgear was the tricorne hat for line infantry and bearskin cap for grenadiers. The infantry weapons were musket, bayonet and hanger small sword. Heavy cavalry wore white coats and hats as for the infantry and were armed with a heavy sword and carbine. Some dragoons wore a bearskin cap. The Austrian army contained a large number of irregular units notably the Pandours from the Balkans who wore their ethnic dress without uniformity. Hungarian Hussars provided the light cavalry arm. These Hussars, dressed as described for the Prussian Hussars, were considered to be little more than bandits but were highly effective in all the roles required of light cavalry.

Following the humiliations of the First and Second Silesian Wars at the hands of Frederick the Great and his Prussian army the Austro-Hungarian authorities implemented wide ranging reforms of every branch of their army. Prince Joseph Wenzel von Liechtenstein after his experience of the devastating effectiveness of the massed Prussian artillery at the Battle of Chotusitz undertook a root and branch reform of the Austrian artillery, using his own fortune to fund the changes. The Austrian artillery that entered the Seven Years War was considered more effective than its Prussian counterpart.

Frederick implemented significant improvements to the Prussian Army between the two Silesian wars. The eleven years of peace before the Seven Years War enabled Frederick to bring the various arms of the Prussian service to a further high pitch of efficiency. Each year the regiments were subjected to a training cycle that culminated in reviews at Potsdam under the King’s exacting eye. Autumn manoeuvres were held in Silesia, the area where much of the expected warfare would be conducted (see the benefit of these manoeuvres at the Battle of Leuthen).

The Prussian infantry was a tested and established asset and required little improvement. Most of the innovation was targeted at the cavalry, artillery and technical arms.

One unfortunate development from the Silesian Wars was that Frederick formed the view that his infantry could win their battles simply by the steadiness of their advance. The Seven Years War began with the Prussian infantry doctrine being to advance with muskets at the shoulder and not to pause to fire on the enemy. The Battle of Prague showed this doctrine to be badly misguided and it was abandoned after causing the Prussians substantial casualties.

The Prussian infantry was then trained to advance making brief halts to fire and reload, enabling it to deliver successive volleys as it marched up to the opposing army, a technique used to devastating effect at the Battle of Rossbach.

During the course of the Seven Years War Frederick extensively re-organised the artillery. New equipment was introduced, the guns standardised and the artillery formations overhauled. Frederick introduced horse artillery that could move around the battlefield.

Frederick brought the Prussian cavalry to a level of effectiveness unrivalled by any other European Army of any period. The basic requirement was a high standard of horsemanship in every soldier. A trooper was required to ride his horse every day, an exacting obligation in peacetime. Contrast this with the practice of the British regiments of horse and dragoons of the time, in which as a measure of economy the horses had their shoes struck off and were put out to grass unridden for the whole of the summer (see Viscount Molesworth’s standing orders for his dragoon regiment).

Every year Frederick exercised the cavalry during the autumn manoeuvres. Frederick required the cuirassier and dragoon regiments to form line at the gallop and deliver a charge, with the troopers so close that they rode knee behind knee with the horses touching. Frederick developed the capability of the cavalry year by year. Finally he required his mounted regiments to be able to deliver three such charges one after the other at full gallop.

Austrian 10th Regiment of Cuirassiers ‘Pfalz-Birkenfeld’: Battle of Lobositz on 1st October 1756 in the Seven Years War: Picture by David Morier

The effect of this exacting training was graphically illustrated by the performance of the Prussian cavalry force led by General von Seydlitz against the Russians at the Battle of Zorndorf on 25th August 1758. Seydlitz’s squadrons crossed the Zabern-Grun stream, climbed the steep far bank and moved through an area of scrub, before forming two lines of hundreds of troopers at the gallop, so close together that the horses were touching, and delivering a devastating charge at full gallop against unshaken Russian infantry, who were overwhelmed. Against cavalry of this quality it mattered little whether the infantry was in line or square.

This extraordinary ability contrasted with most other European cavalry regiments which would form for the charge at the halt and then attack in a loose formation which would be lost in the course of the charge, ending with the horses blown and all cohesion gone. If the infantry under attack seemed unduly aggressive, the attacking cavalry would be liable to swerve around them or pull up.

It was Frederick’s order that any Prussian cavalry commander receiving a charge at the halt would be tried by court-martial. Commanders had the discretion to attack if they considered that a favourable opportunity existed, without waiting for orders.

The Battle of Rossbach is another good example of the quality of the Prussian heavy cavalry and its ability to deliver battle winning charges through remaining under the tight control of its commander.

Prussian Infantry Regiment von

Manteuffel No 17: Battle of Lobositz on 1st October 1756 in the Seven Years War: picture by Adolph Menzel

Background to the Battle of Lobositz:

The Second Silesian War ended with the Treaty of Dresden on Christmas Day 1745. The peace left King Frederick II of Prussia the master of Silesia and the Duchy of Gratz. In spite of the terms of the treaty Maria Theresa had agreed to, Frederick knew that the Austrian Empress would not rest until she had taken Silesia back from Prussian hands. The period between 1745 and the outbreak of the Seven Years War in 1756 was, in effect, only a truce. Austria and Prussia spent this period re-organising and building up their armies and manoeuvring for allies.

In the Silesian Wars Prussia had been allied to France and the other long standing enemy of Austria, the Kingdom of Bavaria. Britain was the traditional enemy of France so King George II had committed Britain to an alliance with Austria. Hanover followed Britain with other Protestant German states and the Netherlands.

For the next and decisive round between Austria and Prussia, the Austrian Chancellor Kaunitz worked to establish an alliance with France. In the final year before the Seven Years War Frederick signed an alliance with Britain, achieving Kaunitz’ aim of pushing France into the arms of Austria. For the French the main enemy in the impending war would inevitably be Britain, with the British threat to the valuable French colony of Canada.

Kaunitz had further successes. The King of Poland, also the Elector of Saxony, committed himself to maintaining the alliance with Austria that had been so disastrous for Saxony in the Silesian Wars.

The final coups were to bring into the Austrian camp the Empress Catherine of Russia and the Swedes.

Account of the Battle of Lobositz:

As it became clear that war was imminent, Frederick resolved not to wait to be attacked by the alliance gathering around Prussia’s borders of Austria, France, Saxony, the Imperial German States, Russia and Sweden. During the early summer of 1756, the Prussian army mobilised and supplies were assembled for the army to take into the field. On 29th August 1756, the Prussians crossed the border into Saxony. The Saxon Army retreated into the fortified camp at Pirna, on the Elbe to the South of Dresden. Frederick marched south, leaving a force to cover the Pirna camp, and on 13th September 1756 his army crossed the southern border of Saxony into Bohemia, over the mountainous Mittel-Gebirge.

On 30th September 1756, in the early morning mists, the leading troops of Frederick’s army emerged into the valley of the River Elbe. An officer from the advance guard warned the king that the Austrian army appeared to be formed in positions around the riverside town of Lobositz. Frederick hurried forward, and, after surveying the scene, ordered his army to advance to the attack.

As the Prussian infantry marched down the valley into the Elbe plain, they passed a lump-like hill called the Lobosch on their left. On their right was the smaller feature, the Homolka. To their front, the valley plain stretched away to the Elbe River beyond the Lobosch. The Morellen-Bach stream flowed in from the far right, around the village of Sullowitz and away into the distance parallel to the main river. Several roads ran along the valley in both directions from Lobositz.

General Franz Moritz von Lacy:

contemporary portrait in the

Heeresgeschichtliches Museum

in Vienna by an unknown artist: Battle of Lobositz 1st October 1756 in the Seven Years War

It would seem that Frederick believed he was facing only a rearguard and that he did not realise that he was in the presence of the whole Austrian army, which was ready to receive his attack.

The main body of Field Marshal Browne’s army lay behind the Morellen-Bach. Significant bodies of cavalry and infantry filled the gap between the stream and the Elbe River, across which ran a sunken road where infantry lay concealed. Sullowitz contained Austrian infantry and guns. General Lacy with a strong force of infantry, many of them Croat and Hungarian irregulars, was moving up the far side of the Lobosch, from their positions on the eastern road out of Lobositz, intending to assail the flank of the advancing Prussian army in the valley beneath the hill.

Prussian heavy artillery moved into position on the Homolka; 24 pounders, 12 pounders and howitzers.

As the Prussian infantry columns emerged into the valley, they came under heavy bombardment from the Austrian batteries positioned outside Lobositz. This was their first experience of the reformed Austrian artillery of Prince Joseph Wendel von Liechtenstein. The fire was returned by the Prussian guns on the Homolka and further batteries on the lower slopes of the Lobosch and in the valley mouth. Casualties were incurred on both sides.

Prussian Infantry Regiment von Bevern No 7: Battle of Lobositz on 1st October 1756 in the Seven Years War: picture by Adolph Menzel

At around 7am, Frederick ordered the Duke of Bevern to take the Lobosch Hill with the three regiments of his brigade, and begin an outflanking move against the Austrian right. A hard fought battle developed on the summit of the Lobosch between Bevern and Lacy.

Frederick, soon after he had launched Bevern onto the Lobosch, despatched a force of cuirassiers under Lieutenant General Kyau, to find out where the Austrian forces were positioned in the central part of the valley. As Kyau came up level with the village of Sullowitz, the Prussians were attacked in the flank by a force of Austrian dragoons. A heavy skirmish ensued in which the Prussians cuirassiers were supported by the Bayreuth Dragoons. Regiments of Austrian cuirassiers joined the melee. The Austrian dragoons disengaged and withdrew, leaving the Prussian cavalry exposed to artillery fire at close range from the Austrians positions around Sullowitz. The Prussian cavalry streamed back across the valley in disorder to the positions held by their infantry.

The remainder of the Prussian cavalry came through from the rear of the army and formed up with the remnants of Kyau’s squadrons, forming a force of 10,000 mounted men. These regiments came under the heavy fire of the Austrian guns. Eventually the Prussian cavalry, acting without orders but galled beyond endurance by the artillery fire, charged the Austrian lines. The charge had no real focus and came to grief along the Morellen-Bach and against the sunken road that led from Lobositz, at the hands of the Croat irregulars who lined the road. Austrian cuirassiers attacked the disordered remnants of the Prussian cavalry.

Frederick sent more of his infantry from the valley onto the Lobosch to support the Duke of Bevern’s assault against the Croats and regular Austrian troops commanded by Lacy.

Field Marshall Maximilian von

Browne, the commander of the

Austro-Hungarian army at the Battle

of Lobositz 1st October 1756 in the Seven Years War

From the Austrian main army positioned behind the Morellen-Bach, which until now had taken little part in the battle, Browne drew up a force around the village of Sullowitz to carry out a counter-attack on the Prussians on the far side of the valley. Before the counter-attack could be launched, the force was dispersed and Sullowitz set on fire by Prussian howitzer fire from the Homolka.

Following this final effort, the Prussian batteries on the Homolka began to run low on ammunition and their fire slackened off, causing considerable concern in the Prussian command.

Finally, when Frederick was despairing of success in the battle and was planning to leave the army with instructions to his generals on the conduct of a withdrawal, the Duke of Bevern pushed the Austrian forces off the Lobosch. The Prussian infantry in the valley moved forward in support and attacked the town of Lobositz, which quickly became a blazing inferno. Browne moved his main body from behind the Morellen-Bach into positions to the south of the town and began a withdrawal, leaving the Prussians in command of the battlefield; the classic sign of victory.

The Prussians won the battle, but the Austrians under Browne put up a spirited and resourceful performance.

Casualties at the Battle of Lobositz: 2,906 Prussian and 2,873 Austrian dead, wounded and missing.

Aftermath to the Battle of Lobositz: Lobositz was far from the classic Frederickian victory. Frederick committed the mistake he was to repeat in later battles of the Seven Years War, attacking with insufficient information on the position and size of the opposing army. On his brief view of the Austrians in the early morning mist, Frederick believed he faced a small rearguard, when, in fact, the whole of Field Marshal Browne’s army was present. The Austrians had spent the peace re-organising their army and the increased effectiveness of their artillery was in particular an unpleasant surprise for the Prussians.

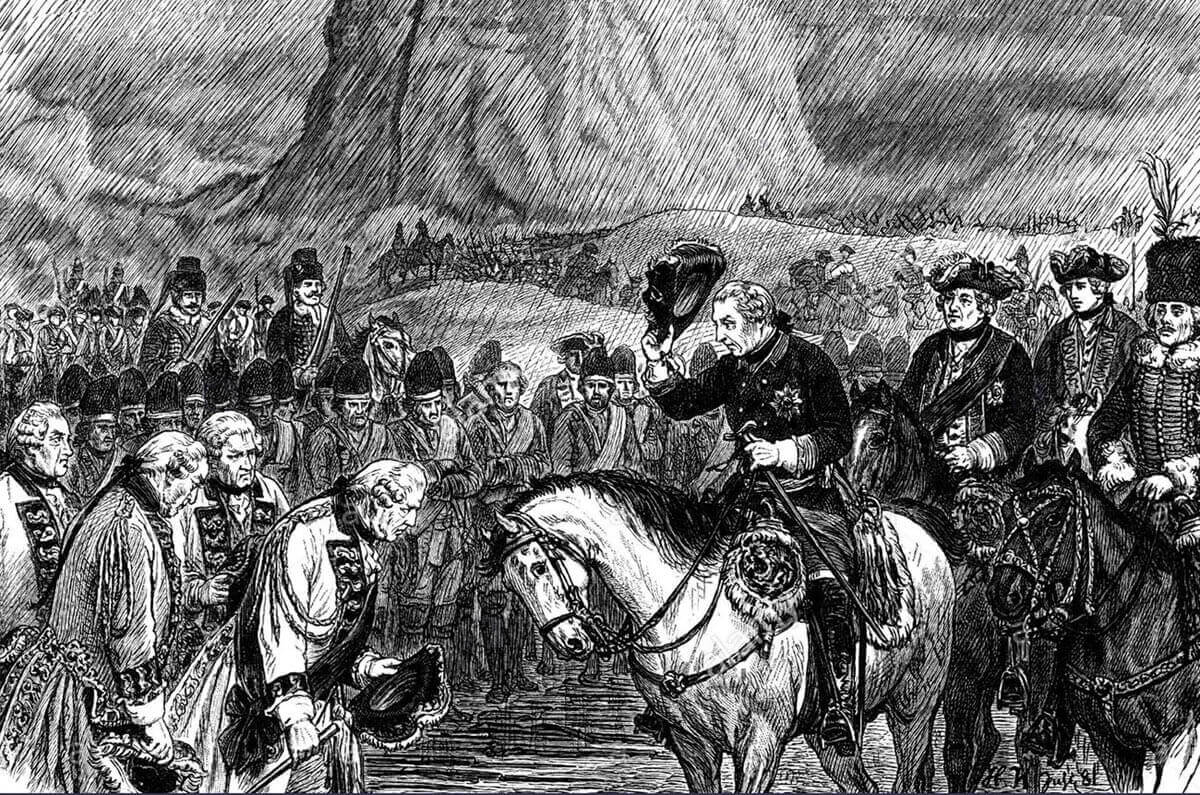

Following the Battle of Lobositz, Browne took an Austrian corps north up the east side of the Elbe to relieve the Saxons besieged in the camp at Pirna. Frederick returned to Pirna leaving Field Marshal Keith to bring his army out of Bohemia.

On 17th October 1756, the Saxon Army surrendered and was incorporated into the Prussian Army. Saxony itself was taken under Prussian administration for the rest of the war.

Surrender of the Saxon Army to Frederick the Great on 17th October 1756 following the Battle of Lobositz on 1st October 1756 in the Seven Years War

Anecdotes from the Battle of Lobositz:

- At the critical moment in the fighting on the Lobosch between the Croats and the Prussian infantry, the Austrian commander on the Lobosch, Lacy, was wounded and incapacitated.

- Frederick supervised the ceremony in which the oath of loyalty to himself was administered to the Saxon regiments. The Saxon soldiers only took the oath with extreme reluctance, and, in the following period, many deserted to the Austrians. Frederick himself beat a young Saxon soldier who refused to swear allegiance to him.

- Field Marshal James Keith, holding a senior command in the Prussian Army at the Battle of Lobositz, was a Scottish Nobleman. The Keiths held the title of Hereditary Earl Marischal to the King of Scotland, fought for Robert the Bruce at the Battle of Bannockburn in 1314 and were out in the Jacobite Rebellion of 1715 against King George I of England. Leaving Scotland after the unsuccessful rebellion, Keith joined the Russian Army, after service in the Spanish Army. Keith resigned, joined the Prussian Army and was quickly promoted to Field Marshal by Frederick. He was said to be universally popular in the Prussian Army. Keith was killed at the Battle of Hochkirch on 14th October 1758.

References:

Frederick the Great by Thomas Carlyle

Frederick the Great by Christopher Duffy

The Army of Frederick the Great by Christopher Duffy

The Army of Maria Theresa by Christopher Duffy

In particular see the detailed and graphic account of the battle in ‘The Wild Goose and the Eagle A Life of Marshal von Browne 1705-1757’ by Christopher Duffy.

The previous battle in the Seven Years War is the Battle of Kesselsdorf

The next battle in the Seven Years War is the Battle of Prague