The capture of Manila by the British in the Seven Years War in 1762:

Possibly Britain’s most successful amphibious operation

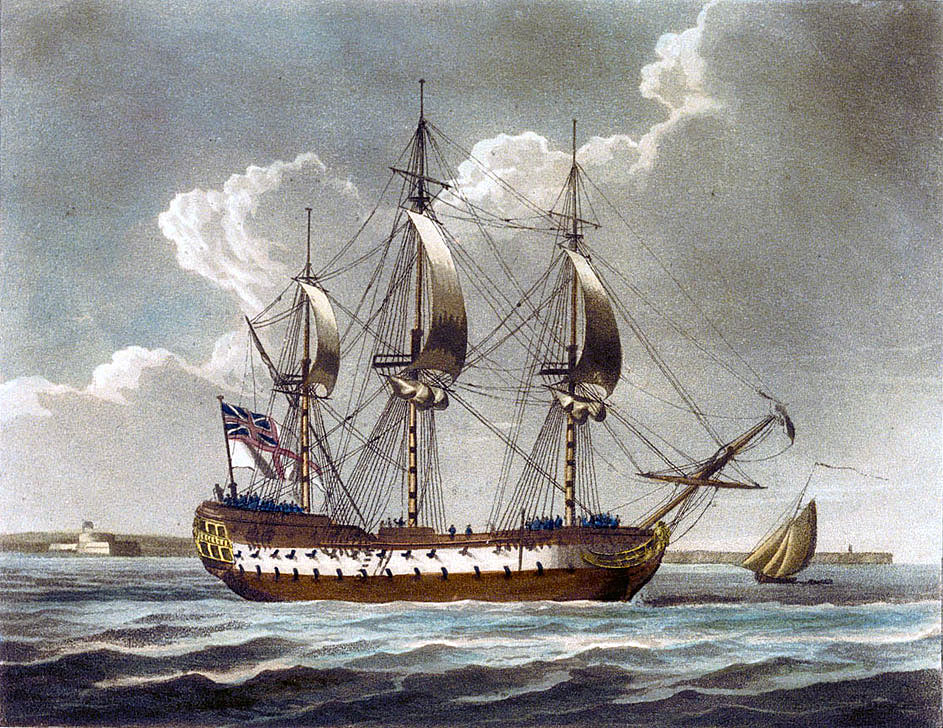

British naval squadron in the 1760s: Capture of Manila 6th October 1762 in the Seven Years War: picture by Dominic Serres

The previous battle of the Seven Years War is the Battle of Wilhelmstahl

The next battle in the British Battles sequence is the Capture of Havana

Battle: The Capture of Manila by the British.

War: The Seven Years War.

Date of the Capture of Manila: 6th October 1762.

Place of the Capture of Manila: in the Philippines.

Combatants in the Capture of Manila: The British against the Spanish assisted by native Indians.

Generals in the Capture of Manila: Brigadier-General William Draper and Rear Admiral Samuel Cornish led the British troops and ships. The temporary governor of Manila was Archbishop Manuel Antonio Rojo del Rio y Vieyra. The senior Spanish military officer was the Marquis de Villa Medina, whose regiment of infantry provided the Spanish troops in the garrison.

Size of the armies in the Capture of Manila: 2,000 British soldiers and sailors and Indian sepoys and French deserters deployed ashore with a fleet of 14 ships against 800 Spanish soldiers of the Regiment of the Marquis de Villa Medina and around 10,000 Indians.

Winner of the Capture of Manila: The British captured Manila on 6th October 1762.

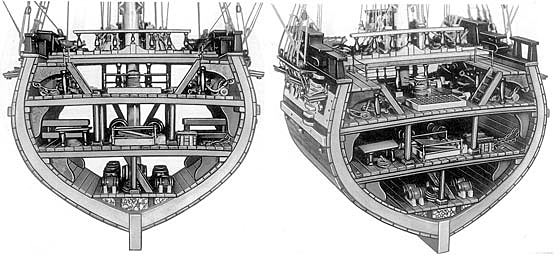

Uniforms, arms and equipment in the Capture of Manila:

The main formation in the British military force was the 79th Regiment. The 79th was formed by Lieutenant-Colonel William Draper in 1757 for service in India against the French. In the course of 4 years service the 79th suffered fatal casualties of 23 officers and around 800 soldiers from battle injuries and disease. By 1762 the 79th was a thoroughly battle hardened regiment. The 79th was disbanded at the end of the Seven Year War in 1763 on its return to Chatham.

The soldiers were equipped with musket and bayonet and small sword or hanger. The uniform was a red coat turned back at the skirts, collar and cuffs worn over a waistcoat. Headgear was the tricorne hat. Brown gaiters were worn over britches, stockings and shoes. No concession was made for the hot climate of India except that the coat was often dispensed with. Ammunition was carried in a leather pouch carried on a cross-belt. The Marines wore a similar uniform to the soldiers. The Royal Artillery soldiers wore a similar uniform in blue.

Royal Navy officers wore a blue uniform coat. No particular uniform was worn by ordinary sailors.

The heavy guns and mortars were probably provided by the fleet. The field guns were probably provided by the Royal Artillery and East India Company.

The sepoys and companies of French deserters were probably clothed in whatever was available from the stores in view of the shortage of time for preparing the expedition.

The Spanish infantry wore a similar uniform to the British but in white.

Background to the Capture of Manila: The Seven Years War is aptly described as a world war. The war’s origins lay in the dispute between Austria and Prussia over Silesia, seized by Frederick the Great, King of Prussia, from the Austrian Empress, Maria Theresa, in 1740 and the overseas disputes between the leading colonial powers, Britain, France and Spain.

General William Draper, British army commander at the Capture of Manila 6th October 1762 in the Seven Years War

The war between Britain and France began in America in 1755. The war in Europe between Britain and her ally, Prussia, and France and Austria began with the Battle of Lobositz in 1756.

In January 1762 Britain declared war against Spain. In June 1762 the British launched an attack against Havana the Spanish port on the island of Cuba.

Lieutenant-Colonel William Draper who was in London on sick leave from his regiment, the 79th Foot in Madras (not to be confused with the subsequently raised Cameron Highlanders), proposed a plan to the Commander-in-Chief, Lord Ligonier, and Lord Anson, the First Sea Lord, to capture Manila, the principal Spanish city in the Philippines in the Pacific. Draper’s plan was to use regiments and ships from India to mount an attack on Manila in the expectation that this could be carried out before news of the outbreak of war between Spain and Britain reached the Philippines. Communication between Spain and Manila was by way of Acapulco on the west coast of Mexico and took significantly longer, often 6 to 8 months, than between London and India.

The plan was adopted and William Draper appointed acting brigadier in command of the military force. Orders were sent with Draper to the East India Company in Madras and to the commander of the East India Squadron, Rear-Admiral Samuel Cornish. The East India Company was directed to release 2 infantry regiments for the expedition.

Manila was a sophisticated city and the centre of the Spanish Pacific trading empire with walls built on the European model.

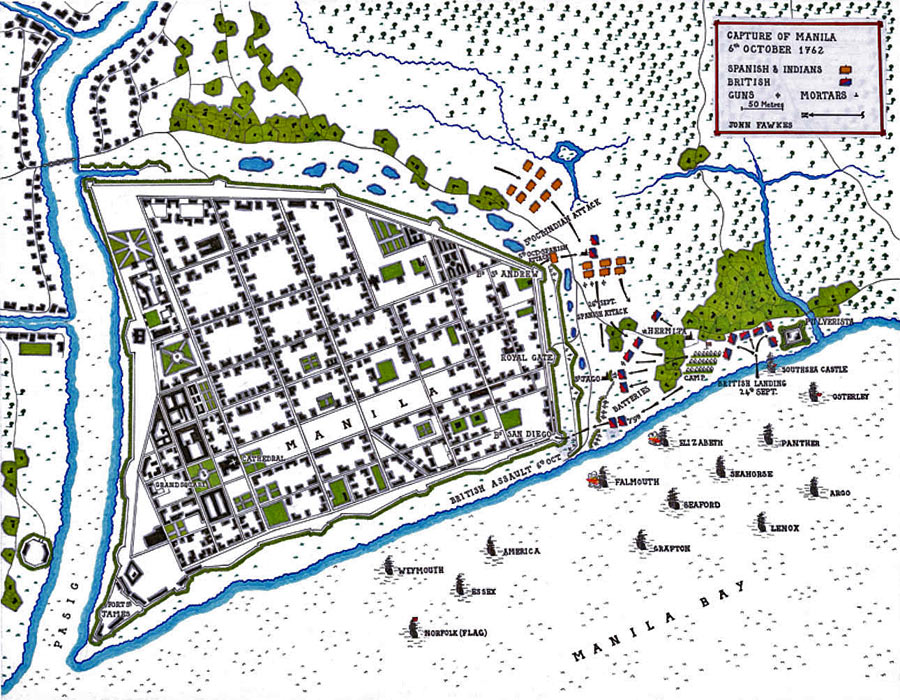

Map of the Siege and Capture of Manila 24th September to 6th October 1762 by the British: map by John Fawkes

Account of the Capture of Manila:

Brigadier William Draper arrived in Madras with his orders in June 1762. The East India Company would only release the 79th Regiment for the expedition with a company of the Royal Artillery and a company of the East India Company’s artillery. Draper recruited a force of 600 Indian sepoys and locals of various nationalities including 2 companies of French deserters; in all a force of some 2,000 men. Several hundred Lascars were recruited to provide carrying and labouring resources as no four legged transport could be taken.

Rear-Admiral Cornish, stationed in India, suffered from no local restraint, simply informing the East India Company authorities that he was ordered to take part in the expedition to take Manila.

Cornish’s squadron for the expedition to Manila comprised 12 ships: HMS Seahorse (Captain Grant), Elizabeth (Commodore Tiddeman), Falmouth, Weymouth (Captain Collins), Panther (Captain Parker), America (Captain Pitchford), Seaford, Grafton, Lenox, Argo (Captain King), Norfolk (Captain Kempenfelt) and Essex. The East India Company provided 2 store ships: Southsea Castle and Osterly.

The co-operation between Army and Navy in the Manila expedition must be nearly unrivalled in British history, other than perhaps in the near-contemporary attack on Havana where the senior officers of the two services were brothers.

Cornish proposed to make up the shortfall in army personnel with a force of 550 sailors and 270 marines from his ships to take part in the operations on land in the Philippines. In the event the naval contribution to the landing force exceeded 1,000.

It was imperative that the fleet sail as soon as possible before the full onset of the South West Monsoon and before the Spanish in Manila became aware of the state of war with Britain. Already there was heavy surf in the Bay of Bengal which severely handicapped the loading of the ships.

As an immediate precaution Captain Grant in HMS Seahorse was dispatched to the Straits of Malacca to intercept any vessel sailing to Manila that might warn the Spanish of the impending attack.

29th July 1762:

Commodore Tiddeman left Madras with HMS Grafton, Lenox, Weymouth and Argos carrying part of the military force to sail to the Malacca Straits and take on water.

1st August 1762:

The rest of the fleet sailed, less Falmouth which was to convoy the Essex carrying East India Company officials to administer Manila, once captured. Loading had been accomplished particularly quickly in spite of the heavy surf in the area of Madras.

Cornish found that he reached Malacca before Tiddeman’s squadron which was becalmed. After watering the ships the fleet left Malacca on 27th August 1762, meeting up with Seahorse off the coast of Borneo on 2nd September 1762.

19th September 1762:

The fleet sighted the coast of Luzon, the northern island of the Philippines on the west coast of which Manila stands, but was driven back out to sea by a north-easterly gale.

23rd September 1762:

The wind veered round to the south-west and moderated enabling the fleet to sail into Manila Bay, anchoring off the fortress of Cavite in the evening.

Falmouth and Essex joined the fleet, but Southsea Castle was missing in the gale. Reconnaissance around Cavite the same night showed that the fortress could be attacked from the sea.

24th September 1762:

The wind veered again preventing an attack on Cavite. Cornish and Draper took 2 frigates up the bay to Manila to see where a landing might be effected. The 2 commanders-in-chief identified a suitable place for a landing about 1 ½ miles south of the city.

The plan had been to take Cavite before moving on to the city of Manila. Cornish and Draper agreed that there was little point in this course. The time spent taking Cavite would put the Spanish in Manila on the alert, whereas the capture of Manila would be likely to lead to the surrender of Cavite.

The fleet approached Manila and at 7pm the soldiers of the 79th Regiment and the marines landed at the point identified by Cornish and Draper. 3 frigates provided a covering bombardment which dispersed the bodies of Spanish troops assembled on the coast. The surf was heavy and all the longboats carrying the landing force were filled with water, damaging weapons and ammunition. There was no opposition and the landing was carried out successfully.

Archbishop Manuel Antonio

Rojo del Rio y Vieyra: Capture of Manila 6th October 1762 in the Seven Years War

A letter was sent to the Spanish Governor calling on him to surrender the city which he declined to do. Due to the death of the civil governor of Manila the post was held temporarily by the Archbishop of Manila, Manuel Antonio Rojo del Rio y Vieyra.

From the moment of landing the Indians skirmished constantly around the British camp and positions firing arrows and attempting to cut off small bodies of men and individuals.

The weather was very bad. It rained for much of the time the British were attacking the city making conditions in the camps and siege works extremely unpleasant and difficult. The strong winds from the south-west ensured there was a constant heavy surf which for much of the time made it impossible to use small boats and endangered the ships of the fleet.

25th September 1762:

To the south of the landing point, at the mouth of a small river, lay a fortress called the ‘Pulverista’ which the Spanish had abandoned. The British troops occupied the Pulverista and used it to cover the landing of the stores and to signal with the fleet.

Colonel Monson with 200 men occupied a large church called the ‘Hermita’ about 900 yards from the city. The church was secured and put in a state of defence by Major More and soldiers of the 79th Regiment and used by General Draper as his headquarters. A further advance was made towards the city walls and another church near the sea called St Jago’s occupied.

In the Bay an incident took place of considerable importance to the fleet. A galley appeared and then turned and made off. It was overtaken and captured by boats from the fleet. Documents onboard showed the galley to be from the galleon, St Philippina. Admiral Cornish ordered HMS Panther and Argo to seek out the St Philippina and capture her. Due to the gale force on-shore winds the 2 ships were unable to leave until 4th October 1762.

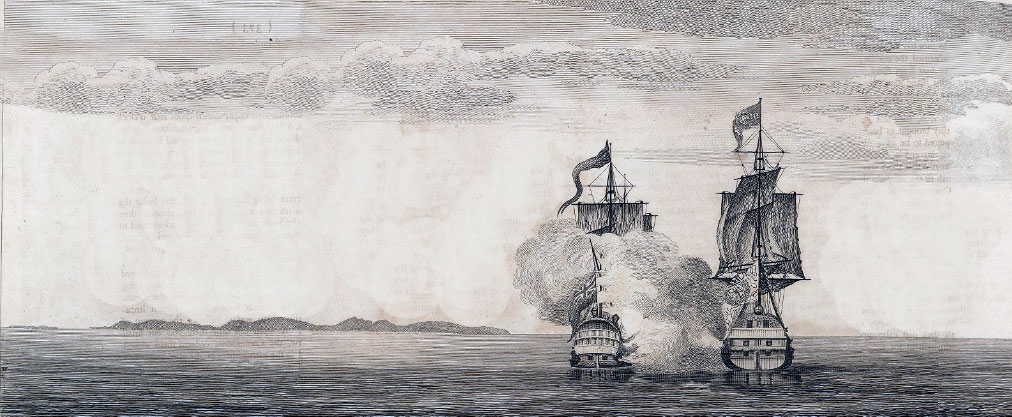

British frigate: Capture of Manila 6th October 1762 in the Seven Years War: picture by Dominic Serres

26th September 1762:

The rest of the landing force went ashore including the seamen and made camp.

A Spanish force sallied out from Manila, comprising 400 men and 3 guns commanded by the Chevalier Fayet. This force approached the British positions around St Jago’s church and opened fire with their guns. Colonel Monson counter-attacked with a force of sepoys, soldiers of the 79th and some others and drove the Spanish back into Manila.

The contrast between the conduct of the British and Spanish troops in this short skirmish was such that the British commanders-in-chief sent another summons to Archbishop Rojo inviting him to surrender the city. The Archbishop’s refusal in reply was written in haughty terms hardly justified by the feeble conduct of his soldiers.

Colonel Monsom took possession of another church further inland from St Jago’s from which it was found that observation could be made of the inside of the city.

Work was begun on an assessment of the state of the defences at the south-west corner of the city and the construction of batteries from which to bombard the city walls. A covered way was built from St Jago’s church to the point where the batteries were to be erected. No attempt was made by the Spanish garrison to interfere with the siege works during this construction other than by counter-fire from the guns in the defences.

29th September 1762:

At the request of General Draper Admiral Cornish dispatched HMS Elizabeth and Falmouth under Commodore Tiddeman to fire on the walls and thereby distract the Spanish from the work of building the batteries. During the discharge of this duty both ships grounded. Fortunately the bottom was soft mud and the ships were able to free themselves. The fire from these 2 ships was reported as being ‘to good effect’.

30th September 1762:

The Southsea Castle arrived, having been separated from the fleet during the storm of 19th September 1762. This was fortunate as the Southsea Castle carried a quantity of stores and in particular the tools needed for the building of the batteries and the covered way. Until Southsea Castle’s arrival the engineers were reliant on such tools as the fleet was able to make in the ships’ forges.

Southsea Castle approached the shore and was driven aground by the wind. What appeared to be a disaster turned out otherwise. Small boats could not easily operate in the stormy conditions. As the Southsea Castle was aground near the shore it proved relatively easy to unload the stores from her. Southsea Castle’s guns provided additional support for the rear of the British camp.

2nd October 1762:

The batteries being complete guns were landed from the fleet; 24 pounders for the gun batteries and 10 and 12 inch mortars for the mortar battery.

HMS Panther and Argo were enabled by a shift in the wind to leave Manila Bay and search for the galleon St Philippina which was thought by the British to be on its way from Acapulco in Mexico to Manila.

4th October 1762:

A heavy bombardment was now commenced against the Bastion of San Diego at the south west corner of the city wall and the neighbouring wall and the ravelin in advance of the wall. This bombardment along with the fire from the fleet took only 4 hours to make a sufficient breach in the Bastion of San Diego.

5th October 1762:

An attack was mounted by around 1,000 Indians on the seamen’s camp. These Indians were said to be from the province of Pampagna. The attack was carried out with great courage and ferocity, but the Indians were only armed with bows and lances. Colonel Monson and Captain Fletcher brought up a force from the 79th and guns were turned on the attackers who were driven off. Captain Porter of the Royal Navy was killed in the fighting.

Immediately after this assault was repulsed a further attack was launched by Spanish troops and Indians sallying out of the Bastion of St Andrew on the church inland from St Jago’s. This church was occupied by the sepoys who were driven out. The British troops positioned behind the church forced their way into the church and drove the Spanish back into the city. In the course of this fighting Captain Strachan of the 79th was killed and 40 soldiers of the 79th killed or wounded. 70 dead Spanish and Indians were found around the church.

It was felt among the British that if the Indians had been carrying modern weapons the outcome of the day’s fighting would have been different. The effect of their defeat seemed to be that large numbers of Indians left Manila for their homes leaving around 1,500 in the city.

That night the commanders-in-chief and other senior officers decided that the assault on the city should take place the next day.

6th October 1762:

The troops assembled at 4am for the assault on Manila in the covered way between St Jago’s church and the batteries and in the batteries’ storage area by the sea. Both batteries opened a heavy fire on the walls.

As dawn broke it could be seen that a large force of Spanish soldiers and Indians was gathered on the Bastion of St Anthony opposite the inland church. This force was dispersed by mortar fire.

Immediately after this incident and under cover of heavy smoke the British assaulting party rushed the breach in the Bastion of San Diego. The party was led by Lieutenant Russell of the 79th with 60 volunteers, followed by the grenadiers of the 79th and then by engineers and pioneers to enlarge the breach if necessary. Next came Colonel Monson and Major More with men from the 79th and the seamen followed with a further party from the 79th. The East India Company’s troops brought up the rear.

The assaulting force rushed straight into the city. There was little resistance except at the Royal Gate where a force of 180 Spanish and Indians holding the guard chamber refused to surrender and were ‘put to the sword’. The British force went on to secure each of the bastions in the city’s wall and the important parts of the city. There was resistance from soldiers in the top storeys of the houses in the Grand Square who were hunted out. Otherwise the Marquis de Villa Medina, his officers and soldiers and the remaining Indians in the city surrendered.

Major More was killed near the Royal Gate, shot by an arrow. Some 30 British soldiers were killed in the assault.

Following the successful assault Admiral Cornish and General Draper met the Archbishop of Manila and his senior officers. A capitulation was agreed whereby Manila, Cavite and the other islands and forts immediately dependent on the city were surrendered to the British along with an agreement to pay 4 million dollars (£1 million) to the British to prevent the city being further sacked.

7th October 1762:

As a consequence of the strong winds Commodore Tiddeman and his barge crew were drowned in the entrance to the river.

31st October 1762:

HMS Panther and Argos came up with the ship the British expected to be the St Philippina sailing from Acapulco in Mexico to Manila. Initially HMS Argos, a frigate, was compelled to engage the Spanish ship alone as Panther was forced to anchor in an adverse on-shore current. Panther then came up and engaged the St Philippina which surrendered after a 2 hour bombardment.

It was found that the Spanish ship was not the St Philippina but the Santissima Trinidad which had sailed from Manila for Acapulco on 1st August 1762 and been dismasted in a storm. The Santissima Trinidad had 800 crew and 40 guns, but only 13 guns were mounted. The ship carried 1 ½ million dollars of cargo and was worth 3 million dollars, a high proportion of which became the prize of the captains and crews of the 2 British ships and Admiral Cornish.

Casualties at the Capture of Manila:

Details of casualties to the extent that they are known are given in the text above.

Follow-up to the Capture of Manila:

The East India Company provided a governor and administration for Manila and the surrounding area. The rest of the Philippines refused to acknowledge British rule and a strong resistance movement, headed by Don Simon de Anda y Salazar, pinned the British to the area of Manila.

The Treaty of Paris was signed by Britain, France and Spain on 10th February 1763 at which time the parties in Europe were unaware of the British capture of Manila. In April 1764 the British left Manila and full Spanish rule resumed.

Regimental anecdotes and traditions of the Capture of Manila:

- Archbishop Rojo is reputed by the British to have told the citizens of Manila that an Angel of the Lord would be sent to destroy the English as in the biblical story of the destruction of the ‘Host of the Sennacherib’.

- Admiral Cornish was made a rich man by the capture of the Santissima Trinidad. General Draper hoped to be equally enriched by the redemption of the bond for £1 million provided under the capitulation of Manila. However the Spanish Government refused to honour the bond and the money was never paid. Draper spent many years pursuing this issue with the British government to no avail.

- General Draper ended his military career as a lieutenant-general with a knighthood. Draper presented the Spanish colours taken at Manila to his old Cambridge college, King’s. General Draper served as the deputy commander on Minorca during the American War of Independence. Minorca was captured by the French.

- The town of Cornish in New Hampshire was named after Vice-Admiral Sir Samuel Cornish.

Royal Navy ships at the Capture of Manila:

- HMS Seahorse (Captain Grant) was a 24 gun sixth rate frigate of the Royal Navy, built in 1748/9. In 1773 Horatio Nelson, the victor of Trafalgar, was assigned to the Seahorse as a midshipman for his first appointment in the Royal Navy. Seahorse’s main armament comprised 22 x 9 pounder guns. Seahorse was finally decommissioned in 1784.

- HMS Elizabeth (Captain Tiddeman) was a 64 gun third rate of the Royal Navy built in 1706 and broken up in 1766.

- HMS Falmouth was a 50 gun fourth rate launched in 1752. As a result of the damage suffered during the attack on Manila Falmouth was beached and abandoned in Batavia (Indonesia) in January 1765.

- HMS Weymouth (Captain Collins) was a 60 gun fourth rate launched in 1752 and broken up in 1772.

- HMS Panther (Captain Parker) was a 60 gun fourth rate launched in 1758. She served as a hospital ship from 1791 and a prison hulk for prisoners of war from1807. She was broken up in 1813.

- HMS America (Captain Pitchford) was a 60 gun fourth rate launched in 1757 and broken up in 1771.

- HMS Seaford was a 22 gun sixth rate launched in 1754 and sold in 1784.

- HMS Grafton was a 70 gun third rate launched in 1750 and sold in 1767.

- HMS Lenox was a 74 gun third rate launched in 1757 and sunk as a breakwater in 1784.

- HMS Argo was a 28 gun sixth rate frigate launched in 1758 and broken up in 1776.

- HMS Norfolk (Captain Kempenfelt) was a 74 gun third rate launched in 1757 and broken up in 1774. Norfolk was Admiral Cornish’s flag ship at Manila.

- HMS Essex was a 64 gun third rate launched in 1760 and was sold in 1799.

References for the Capture of Manila:

- A Complete History of the Late War published by John Exshaw

- A History of the British Army Volume II by John Fortescue

- Documents illustrating the British conquest of Manila 1762-1763

- Manila Ransomed: The British Assault on Manila in the Seven Year War by Nicholas Tracy

The previous battle of the Seven Years War is the Battle of Wilhelmstahl

The next battle in the British Battles sequence is the Capture of Havana