The capture of the Spanish port of Havana on the island of Cuba on 14th August 1762 in the Seven Year War by the Royal Navy and the British Army in a notably successful combined operation

Podcast on the Capture of Havana: The capture of the Spanish port of Havana on the island of Cuba on 14th August 1762 in the Seven Years War by the Royal Navy and the British Army in a notably successful combined operation: John Mackenzie’s britishbattles.com podcasts

The previous battle of the Seven Years War is the Capture of Manila

The next battle in the British Battles sequence is the Siege of Arcot

Battle: Capture of Havana

War: Seven Years War or French and Indian War

Date of the Capture of Havana: 14th August 1762

Place of the Capture of Havana: On the north-west coast of the Island of Cuba in the Caribbean Sea

Combatants at the Capture of Havana: British against the Spanish

Commanders at the Capture of Havana: Lieutenant General Lord Albemarle commanded the British land forces. Admiral Sir George Pocock commanded the Royal Navy fleet of warships.

Don Juan de Prado was the governor of Cuba.

Commodore El Marquis del Real Transporte was commander in chief of all his Catholic Majesty’s Ships in America and commander of the Spanish warships in Havana.

Size of the armies at the Capture of Havana: The British troops numbered 12,500, according to the return made from Cape St Nicolas on 23rd May 1762 before the landing at Havana (with the addition of 500 Royal Artillery personnel). Around 3,500 additional troops arrived from America at the end of July 1762, but by then Albemarle’s army had suffered significant losses from disease.

Pocock’s Royal Navy fleet comprised the following HM warships: Namur 90 guns (flag ship), Valiant 74 guns, Cambridge 80 guns, Culloden 74 guns, Temeraire 74 guns, Dublin 74 guns, Dragon 74 guns, Temple 70 guns, Marlborough 68 guns, Orford 66 guns, Belleisle 64 guns, Hampton Court 64 guns, Stirling Castle 64 guns, Devonshire 66 guns, Pembroke 60 guns, Ripon 60 guns, Nottingham 60 guns, Edgar 60 guns, Defiance 60 guns, Sutherland 50 guns, Dover 44 guns, Alarm 38 guns, Echo 22 guns, Mercury 22 guns, Cygnet 18 guns, Thunder 10 guns, Grenado, Bonetta, Basilisk bomb ships, Lurcher cutter.

HMS Hussar was lost off Cape Francois before Pocock’s Fleet began the voyage up the Old Bahamas Channel.

In addition, there were some 150 merchant ships carrying troops, equipment and supplies.

The Spanish garrison numbered between 5,000 and 10,000 men comprising regular Spanish troops and local militia. Numbers are not known precisely and varied with the number of local militia available.

There was a substantial force of Black African slaves and freed slaves in Havana. Slaves were offered their freedom for service in the garrison.

Winner of the Capture of Havana: The British captured Havana and western Cuba.

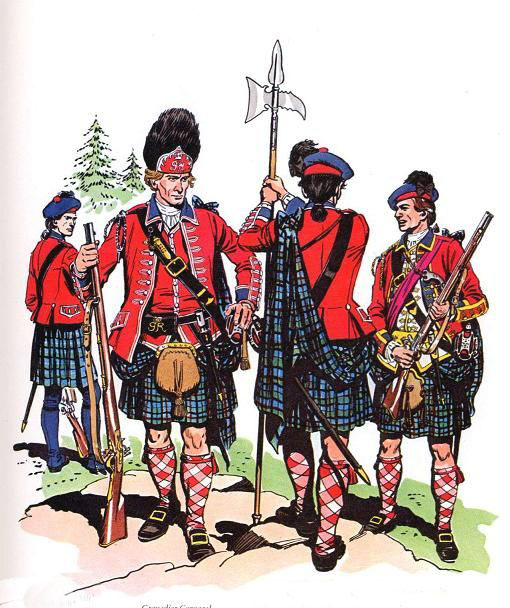

British order of battle:

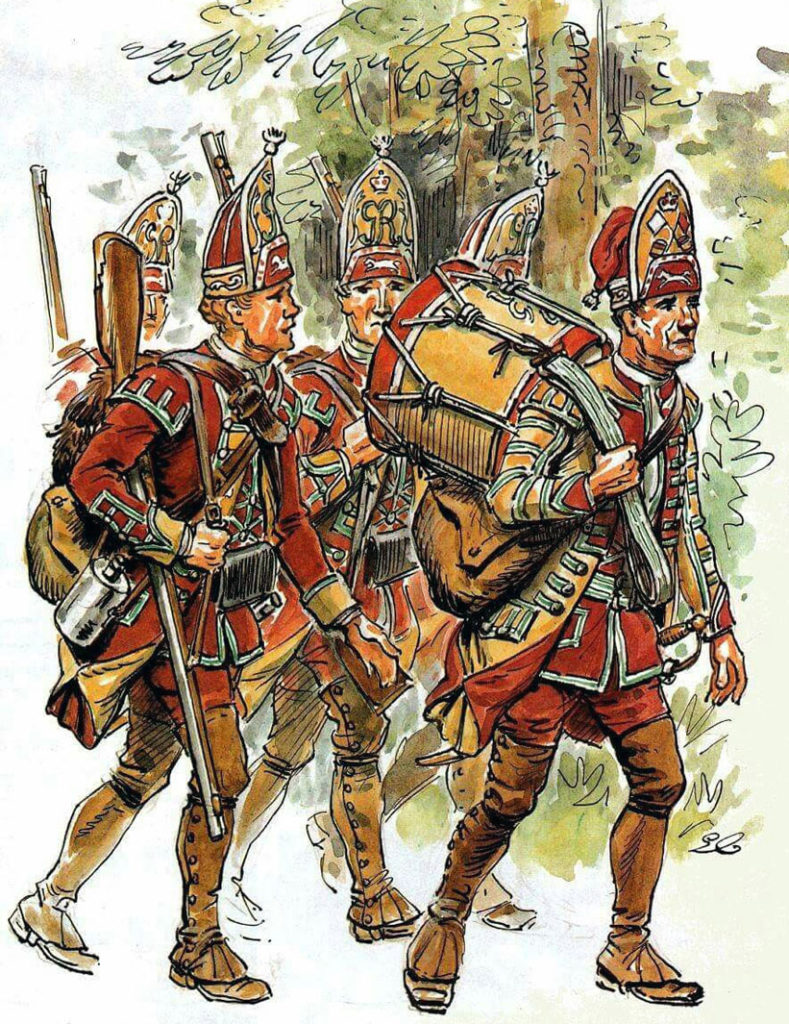

The regiments that accompanied Lord Albemarle from England were the 22nd, 34th, 56th, 72nd Regiments and Freron’s Regiment of French Protestants (ex-prisoners of war).

The other regiments were in Monkton’s force for the capture of Martinique in the West Indies, some of which came from the garrison on Belleisle in the Bay of Biscay (69th, 76th, 90th and 98th) and the remainder from North America.

In a return dated 23rd May 1762 from ‘Off St. Nicolas” (i.e. ‘at sea) in the West Indies these regiments were listed as ‘Under the command of Lieutenant General Lord Albemarle’: 1st, 4th, 9th, 15th, 17th, 22nd, 27th, 28th, 32nd, 35th, 40th, 1st and 2nd Battalions of 42nd, 43rd, 48th, 56th, 3rd/60th, 65th, 72nd, 77th, 90th, 95th Regiments (it is not apparent why the 34th is not included in this return).

The total of troops given in the return was 11,998 (perhaps 12,500 with the 34th), of whom 1,289 were sick.

There were probably some 500 Royal Artillery personnel with Albemarle’s army.

At the end of July 1762, the 46th and 58th Regiments, Gorham’s Rangers and other provincial troops commanded by Colonel Burton joined Albemarle’s army.

Spanish troops in Havana:

Infantry Regiments of Spain and Aragon

Dragoon Regiment of Edinburgh

Regiment of Artillery

Regiments of Regular and Irregular Militia.

Background to the Capture of Havana:

The Seven Years War broke out in 1756, with fighting between Britain and France in North America, the West Indies, Europe and India.

In Europe the war was fought between Britain and Prussia against Austria, Russia, Saxony and France.

The war is notable for France’s loss of its colony of Canada to Britain and a number of other colonies in the West and East Indies.

In 1761, when the war had only two years to run, King Carlos III of Spain signed a secret treaty of mutual defensive and offensive support with his fellow Bourbon, King Louis XVI of France.

The main area of contention between Spain and Britain was the West Indies and America.

On 4th January 1762, after discovering the existence of the secret treaty Britain declared war on Spain.

Britain’s ambition was to capture major portions of the Spanish West Indies and American and Pacific Empire.

While a British naval and military force was sent from India to take Manila in the Philippines in the Pacific Ocean, the main British move against Spain was an expedition to capture Havana on the Island of Cuba in the West Indies and then go on to take Louisiana.

Havana, on the north-west coast of Spanish Cuba, was one of the primary ports in the Spanish American colonies. The Spanish ‘Flota’, the annual transport of gold and silver from America to Spain, assembled at Havana.

The idea of an attack on Havana may have come from Admiral Sir Charles Knowles, a British sea officer with extensive experience of fighting the Spanish and French in the Caribbean, from the abortive British attempt to capture the Spanish port of Cartagena in 1742 onwards.

Knowles was governor of Jamaica from 1752 to 1756. In 1756 Knowles accepted an invitation from the Spanish governor to visit Havana.

An expert on engineering and fortifications, Knowles carefully examined the defences of Havana and sent a report outlining a plan for an attack on Havana to the Prime Minister, William Pitt.

Pitt laid Knowles’ plan with his own recommendations for such an operation before the Cabinet at the time of his resignation in 1761.

The new Prime Minister, Lord Bute, while opposed to continuing the war in Europe, was beguiled by the success of the attack on the French Island of Martinique and readily gave his assent to the operation against Havana.

The Duke of Cumberland, while no longer the Captain-General of the Army, still wielded considerable influence in Britain’s military and naval affairs. Knowles was a companion of the Duke of Cumberland, having a room at the Duke’s residence of Cumberland Lodge.

It seems clear that Cumberland, with Knowles’ guidance, was a major source of direction for the Havana operation, influencing the appointment of the senior officers for the expedition and advising on how the operation should be conducted.

Another major inspiration for the planning of the attack was Lord Anson, the First Sea Lord.

Command of the army to attack Havana with the rank of lieutenant general was given to the Third Earl of Albemarle, a protégé of the Duke of Cumberland, almost certainly on Cumberland’s insistence.

Command of the fleet for the expedition went to Admiral Sir George Pocock.

Other key army appointments were: Lieutenant General George Elliot as second in command to Albemarle, Major General John Lafausille, Major General William Keppel Colonel Guy Carleton and Colonel William Howe.

Lieutenant Colonel Patrick McKellar was appointed chief engineer, a key appointment, McKellar having experience from the taking of the fortresses of Louisberg and Quebec from the French.

The artillery was commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Alexander Leith and on his death during the campaign by Lieutenant Colonel Samuel Cleaveland.

For the fleet, Commodore Augustus Keppel became Pocock’s deputy.

In preparing the Havana expedition, the British Government had in mind the lessons from the abortive attack on the port of Cartagena in 1742, when the British army and fleet were decimated by disease and the operation failed, substantially due to the animosity between the army and navy commanders and their refusal to co-operate with each other.

For the Havana expedition two of the senior officers, General William Keppel and Commodore Augustus Keppel, were younger brothers of the army commander, Lord Albemarle.

The troops for the Havana expedition were to come from three sources.

Albemarle and Pocock would sail with the artillery and four British regiments of foot from England; the 22nd, 34th, 56th, 72nd.and Freron’s Regiment of French Protestants.

The expedition’s initial destination was Martinique, where it would take over General Monkton’s regiments, hitherto involved in capturing Martinique and other West Indies islands from the French.

By letter dated 13th January 1762, Lord Egremont, the Secretary of State for the Southern Department, wrote to Sir Jeffrey Amherst, the British Commander in Chief in North America, in New York, informing him of the expedition against Havana and directing him to send 4,000 troops to take part in the operation.

Egremont directed that the troops from America should arrive at Havana in April 1762 or the beginning of May 1762 at the latest.

By letter dated 5th February 1762, the Admiralty wrote to Rear Admiral Rook, the naval commander of the attack on Martinique, directing that the ships and soldiers of the Martinique operation were to be immediately moved to Prince Rupert’s Bay in Dominica to join Pocock’s and Albemarle’s fleet, unless St Lucia or Martinique might be more convenient.

Secret instructions dated 15th February 1762 to Albemarle directed him to rendez-vous with Monckton’s troops at Barbados and Amherst’s troops off Cape St Nicolas, at the north-western end of Hispaniola/Ste Domingue. However, he was not to wait for Amherst’s troops if they were not at the rendez-vous, but to push on to Havana.

On 24th February 1762 Pocock’s fleet sailed from Spithead for the West Indies.

Havana:

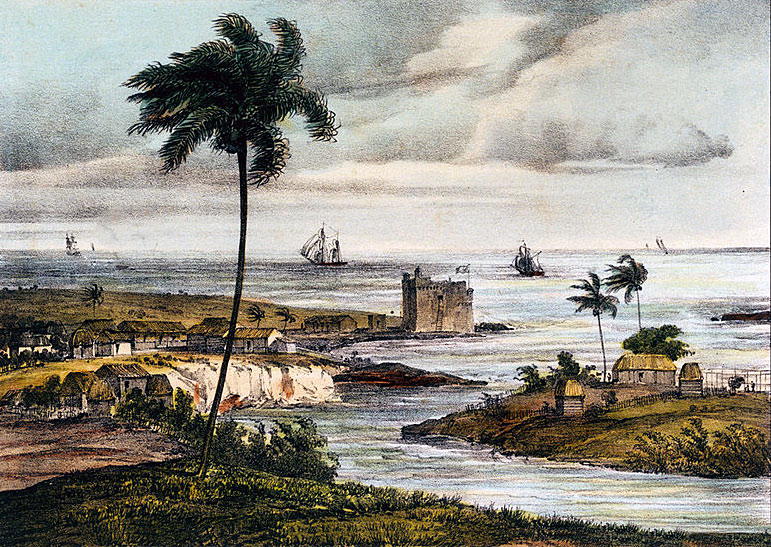

The port city of Havana, on the north-western coast of the Spanish island colony of Cuba was established in the early 16th Century.

Havana’s fine harbour ensured that it became the most important port in the Spanish American colonies.

Subjected to pirate attacks in the 17th Century, the Spanish Crown built extensive defences for the port city.

By the 1750s Havana had grown to be the third largest Spanish city in the Americas, more populous than Boston or New York.

It contained the largest Spanish ship yard, was the base for a strong Spanish naval squadron and the rendez-vous for the treasure ships sailing between the Spanish South American colonies and Spain.

The Spanish considered the defences of the city to be extremely strong, if not impregnable.

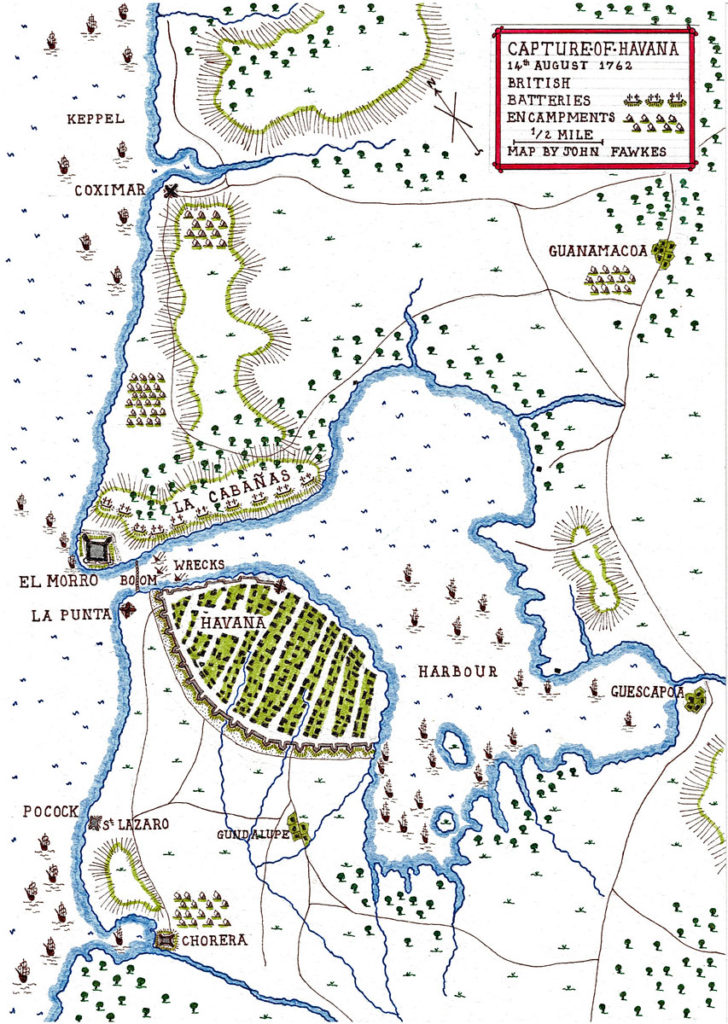

Havana lay on the western side of a fine natural harbour reached from the sea by a mile-long channel.

The entrance to the harbour was defended on the western side by the Puntal Fort.

The key defensive work was the castle of El Morro on the raised eastern headland of the harbour entrance.

El Morro’s guns could fire on ships attempting to enter the harbour or on any force attempting to take the fortress of Puntal on the western headland of the harbour entrance or assaulting the city walls from the northern end.

The weakness in the Havana defences lay in the wooded La Cabañas ridge on the east side of the harbour, from which an attacker’s guns could bombard the city, ships in the harbour and El Morro Castle.

Instructions were repeatedly given by the Spanish authorities, including the king himself, to the governor of Cuba, Don Juan de Prado, for the La Cabañas ridge to be fortified, but no action was taken.

La Cabañas ridge was left a heavily wooded area devoid of defences south of El Morro Castle.

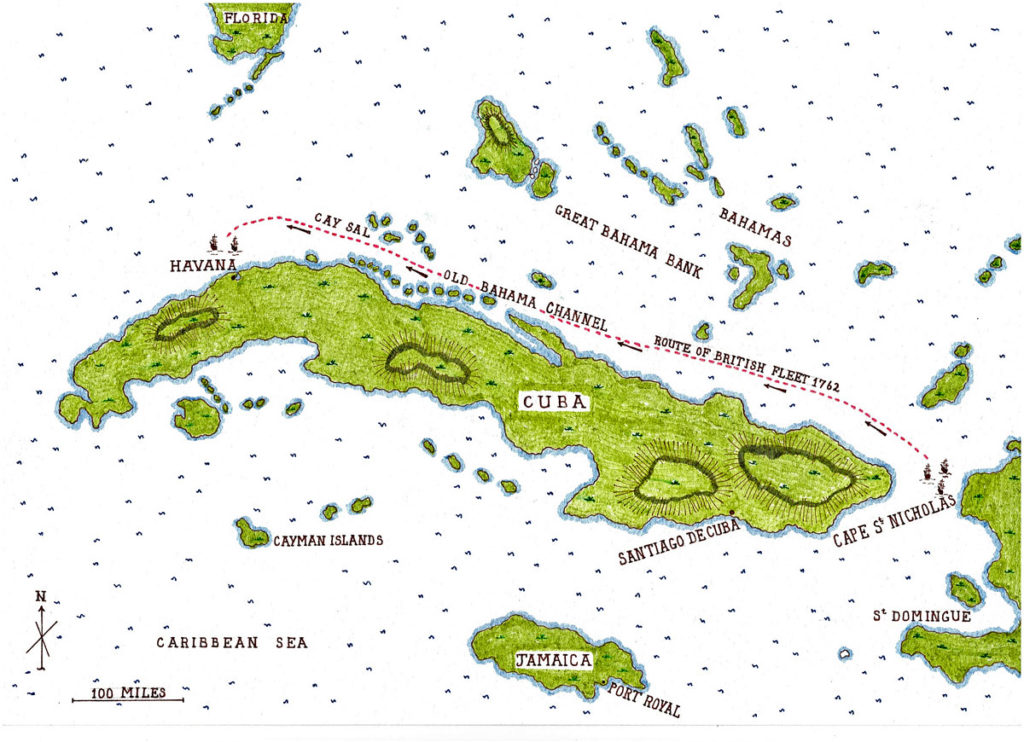

Routes to Havana:

The conventional route to Havana from North America or Europe was to sail along the southern coast of the island of Cuba from east to west, round the western end of the island and approach Havana from the west, beating back against the prevailing easterly winds.

A fleet using this route was likely to be in sight of the Havana defences for a significant period before it could reach the city and would be seen by other ships leaving and arriving at Havana.

The shorter direct route from Europe or North America, along the northern Cuban coast was not used by shipping as it went through the Old Bahama Channel, lined on each side by shoals, outcrops of land and other shipping hazards.

The British Fleet’s approach to Havana:

The British plan was for the fleet to approach Havana by way of the Old Bahama Channel along Cuba’s northern coast. This route was directed by the Admiralty’s instructions to Admiral Pocock dated 18th February 1762 and was clearly part of the earliest plans for the expedition.

Provided the dangers of the northern route could be managed, the advantages were substantial: the approach would be quick, the prevailing winds being easterly and it was unlikely there would be other shipping that might warn the Spanish in Havana of the British approach.

A trawl of the area by the Royal Navy authorities in Jamaica in the early months of 1762 failed to find a single pilot with knowledge and experience of the Old Bahama Channel route, other than one nearly blind 80-year-old.

The approach of Pocock’s Fleet to Havana was timed to catch the Spanish authorities in Cuba unprepared, closely following the declaration of war on Spain by Britain on 6th January 1762.

The plan relied upon using British resources in the West Indies and America in addition to the force transported in Pocock’s fleet from England.

The instructions sent to Rodney and Monckton on Martinique and to Amherst in America made assumptions as to the position and availability of their forces, there being no current information available to the authorities in London.

When, on 22nd March 1762, Rodney’s orders arrived in Martinique on board HMS Richmond for his ships and Monckton’s regiments to join the Havana force, Rodney was about to send several of his ships to Jamaica in the light of local intelligence that the French were preparing to attack Jamaica.

In spite of these orders Rodney sent 10 of his ships to Jamaica.

From Jamaica, on 19th April 1762 Captain Elphinstone in HMS Richmond was despatched with a sloop to carry out a survey of the Old Bahama Channel and meet Pocock with the information gathered.

Arrival of the British Fleet in the West Indies:

Pocock’s Fleet arrived in Martinique on 20th April 1762. The army was there landed, re-organised and with Monckton’s troops re-embarked on the fleet.

On 6th May 1762, Pocock’s fleet sailed from Martinique.

With a further convoy from England, the fleet numbered more than 200 ships.

On 17th May 1762, Pocock’s fleet arrived off Cape St Nicolas at the western end of the island of Sainte Domingo/Hispaniola.

Due to the dispersion of the ships of Rodney’s squadron it was not until 25th May 1762 that Pocock’s Fleet was finally assembled for the descent on Havana.

The search for pilots with knowledge of the Old Bahama Channel being unsuccessful, Pocock formed his fleet into three divisions with strict orders to each of the division commanders on how to conduct the voyage along the channel.

A flotilla of smaller ships was sent ahead, with instructions to mark areas of shoal and the headlands, by mooring manned boats and lighting bonfires.

On 29th May 1762, the fleet met the returning HMS Richmond with her survey of the Old Bahama Channel, considerably simplifying the journey along the Cuban coast.

Pocock’s Fleet arrived off Havana on 6th June 1762, taking the Spanish by surprise.

In Havana, the British declaration of war against Spain was only a rumour, the official notification from Spain having been on board a ship captured by a British warship.

Reports came in of the arrival of ships off Havana as Prado and the city dignitaries were in church, celebrating the feast of the Trinity. Prado’s reaction was that it must be a passing fleet, until British troops began to land.

The Attack on Havana:

The senior officers of the British expeditionary force, before the arrival of the fleet off Havana, planned the assault on the city relying on an assessment of the defences prepared by the chief engineer, Lieutenant Colonel Patrick McKellar, from the descriptions and maps of the defences prepared by Admiral Knowles and other British naval officers with knowledge of the city.

The main focus of the attack was El Morro Castle. Once El Morro was captured it was considered that the city could no longer be defended.

To this end the British landings began on 7th June 1762.

While Pocock with part of the fleet demonstrated at Chorera, a river inlet 1 mile to the west of the city, the main landing was carried out, under Commodore Keppel’s direction, east of Coximar, 2 miles to the east of the city.

4,000 troops were rowed ashore and advanced along the beach to the fort at Coximar, where 600 Spanish militia manned a breastwork. In the face of a naval bombardment, the Spanish militia abandoned the breastwork and retreated to the Cabaña Heights.

On 8th June 1762, Colonel Carleton, with a force of British light infantry, advanced to the village of Guanabacoa, 2 ½ miles inland from Coximar, taking the village after a short fight against Spanish cavalry and militia.

Only after the British began to land did the Spanish Governor, Del Prado, prepare his defences, a clear indication of the complete surprise achieved by the British.

Spanish troops occupied the heights of La Cabaña on 7th June 1762, bringing guns over from the city.

A chain boom was placed across the mouth of the harbour and two ships of the line sunk behind the boom, with another added some days later (Neptuno, Asia and Europa).

The guns and crews of several of the remaining warships were removed to add to the defences of the city and El Morro Castle.

Don Luis de Velasco, captain of the warship Reina, was appointed commander of El Morro, a role he performed with courage and resource, until his mortal wounding during the final storming of the castle.

On 8th June 1762, British patrols probed the lower slopes of La Cabaña, causing many of the Spanish to abandon the heights and withdraw to the city. The Spanish withdrawal was conducted in some disorder, guns being thrown into the harbour. A small Spanish contingent remained on the heights.

On 10th June 1762, Colonel Howe advanced onto the heights of La Cabaña and invested the landward side of El Morro Castle.

On the western side of the city, Admiral Pocock launched a heavy diversionary raid, with his ships bombarding the forts at Chorera and St Lazaro and the woods behind them.

The British bomb vessels threw shells into the northern parts of the city.

Marines were embarked, as if for a full landing and for a time a party took over the fort of Chorera, abandoned by the Spanish.

To the east of the city, at 1pm on 11th June 1762, Colonel Guy Carleton led the British light infantry and grenadiers in driving the Spanish off La Cabaña heights.

The importance of the heights to the defence of Havana was clear to both sides.

Giovanni Battista Antonelli, when designing the defences for Havana in the 16th Century is reputed to have said ‘The city will be mastered if La Cabaña is taken.’

The Spanish King Charles III had issued precise orders to the governor of Havana, Don Juan de Prado, directing him to fortify La Cabaña, but nothing was done.

The capture of the Cabaña heights enabled the British to install gun batteries dominating the harbour and the city and to bombard the crucial El Morro Castle.

Tropical disease on Cuba:

Whether Havana survived the British attack was now a matter of time. The longer El Morro Castle could hold out and prevent the collapse of the Spanish defence the more likely it was that casualties from disease would force the British to abandon the attack on Havana altogether.

The endemic diseases of the Caribbean were yellow fever and malaria, both mosquito-borne.

Once troops landed and moved into the country, particularly low-lying wet areas, they became susceptible to these diseases and casualties began to mount. The British commanders had to capture Havana while they still had enough troops on their feet to man the guns and provide assault parties.

Additionally, the capture of Havana had to be completed before the onset of the hurricane season at the end of August forced the withdrawal of the British fleet.

British operations on La Cabaña and against El Morro Castle:

The land operations against El Morro Castle were commanded by Major General William Keppel, the commander-in-chief, Lord Albemarle’s brother.

On 12th June 1762, the British reconnoitred the ground around El Morro and the Cabaña Heights.

Batteries were to be built to batter down the defences of El Morro Castle and others along the Cabaña Heights to fire into the city and at the ships in the harbour.

Building the batteries was handicapped by the thick woods along the ridge and the lack of depth of earth.

Entrenchments could not be dug, but had to be erected using fascines, longer to build and more vulnerable to counter-battery fire.

To draw Spanish attention away from the battery construction, two British bomb ships, HMS Basilisk and Thunder, bombarded El Morro Castle, while ships commanded by Pocock anchored at Chorera and four British ships of the line cruised off the harbour entrance.

On 15th June 1762, a force of 800 marines and two thousand light infantry and grenadiers led by Colonel Carleton landed at Chorera.

The landing at Chorera was initially designed to draw Spanish troops away from El Morro. Chorera proved a more secure anchorage than Coximar and a good source of fresh water for the British troops and ships, so the troops remained ashore and consolidated their positions there.

The construction of batteries continued on the Cabaña heights and facing El Morro Castle in the face of heavy Spanish bombardment from the Spanish warships and El Morro itself.

The largest British battery on La Cabaña came to be known as the ‘Spanish Battery’, being on the position held by the Spanish before they were driven off by Carleton.

The British were forced to bring their equipment and supplies for the construction and manning of the batteries and the ammunition for the guns over the two-mile track from the ships at Coximar, while the Spanish access to El Morro was by boat across the harbour.

The Spanish maintained the health and morale of the El Morro garrison by replacing the troops every few days with fresh manpower from the city.

In the early hours of 29thJune 1762, the Spanish landed a force of 260 troops and seamen on the shore of the Cabaña heights, while 500 Spanish left the fortifications of El Morro Castle to attack the British mortar battery on the coast.

The British troops were alert and repulsed both attacks, inflicting 73 casualties on the Spanish against a handful of British casualties.

On the next day the batteries were completed and opened fire on El Morro Castle.

The bombardment of El Morro Castle by ships of the Royal Navy:

From the arrival of the British fleet off Havana the Royal Navy officers considered that a naval bombardment might well compel the surrender of El Morro Castle.

On 9th June 1762, Captain Hervey of HMS Dragon, 74 guns, conducted a reconnaissance of El Morro and submitted a report to Pocock urging a naval bombardment.

Lord Albemarle and Commodore Keppel were not keen on the idea of a naval bombardment of El Morro. Nevertheless, Admiral Pocock ordered a more detailed reconnaissance.

On the night of 11th June 1762, three ship’s boats from HMS Marlborough, Cambridge and Culloden made soundings at the base of the cliff and found the sea was deep enough for ships to anchor inshore close to El Morro Castle.

It seems it was too dark for the boats’ crews to assess the height of the castle walls above the sea and whether ships’ guns could reach them. In the event they could not.

On 1st July 1762, a bombardment was opened on El Morro Castle from four land batteries.

The plan was for four Royal Navy ships HMS Stirling Castle, Captain James Campbell, 64 guns, HMS Dragon, Captain Hervey, 74 guns, HMS Cambridge, Captain Goostrey, 74 guns and HMS Marlborough, Captain Burnett, 68 guns, to approach close in to El Morro Castle and begin a bombardment at the same time.

The Royal Navy ships were delayed in approaching El Morro Castle through HMS Dragon losing an anchor and lack of wind.

Of the Royal Navy ships, Stirling Castle was to take the lead and draw the fire from El Morro, enabling the other three ships, Dragon, Cambridge and Marlborough to take up positions close to the shore and begin the bombardment of El Morro Castle.

Instead of taking the lead, Campbell’s ship lagged badly behind the other ships, Campbell giving the excuse that he had left some of his key sails ashore. This appeared to be untrue as the other ships could see the sails furled on Stirling Castle’s spars.

Soon after 9am the bombarding ships, Cambridge, Dragon and Marlborough were in position and opened fire.

The smoke from each sides’ gunfire filled the narrow sea passage concealing the effects of the firing, which in the case of the Royal Navy had virtually no effect, the shots hitting the cliff below the walls and in the case of the Spanish gunfire, while too high to hit the ships’ hulls, severely damaged the rigging and sails of the three Royal Navy ships.

Within minutes of the attack beginning, the rigging of the leading ship, HMS Cambridge, was in tatters, a number of her guns dismounted and the captain killed. Dragon went aground, still firing.

Hervey signalled for the captain of HMS Trent to go aboard Cambridge and take command.

HMS Sterling Castle finally caught up with the other three ships of the squadron but took little part in the bombardment.

Hervey ordered Campbell to drop a heavy anchor off the bow of Dragon and pass a heavy cable to Dragon to enable her to kedge away from the cliff.

Instead of obeying Hervey’s order, Campbell sent a boat with a light anchor and a small hawser to Dragon, which were of no use, leaving Dragon to kedge away from the cliff, using her own stream anchor dropped by boat.

At around 11am Commodore Keppel ordered Hervey to abandon the attack, but by then Hervey’s ships were ceasing fire and withdrawing.

The Royal Navy ships suffered casualties of 192 officers and men killed or wounded, with extensive damage inflicted on the ships involved.

The one benefit for the British was that the Spanish garrison of El Morro Castle concentrated its fire on the ships, leaving its landward defences severely out-gunned by the British shore batteries.

Captain James Campbell of HMS Stirling Castle was tried by a court-martial of captains of the fleet and dismissed the service, having given no satisfactory explanation for his conduct during the action.

Destruction of the British Grand Battery:

On the second day of the British bombardment of El Morro Castle, the Grand Battery, housing eight 24 pounder guns and two 13-inch mortars, caught fire, sparks from the guns igniting the wooden beams of the parapets.

Little water was available to combat the flames and over a period of days the Grand Battery was destroyed. The slackening of the British cannonade while the fire was dealt with enabled the Spanish garrison in El Morro Castle to re-mount a number of guns previously put out of action and build up a strong counter-battery fire.

An increasing problem for the British troops on La Cabaña was disease, the heat and a shortage of water.

Many of the soldiers fell ill and Royal Navy sailors were brought in to man the batteries and build new field works.

Due to the shortage of soldiers fit for duty the British withdrew from the village of Guanabacoa to maintain the strength of the force holding La Cabaña.

It was observed by British officers that the troops on the heights were healthier than those in the swampy country around Guanabacoa.

The British batteries, using 24 pounder cannon and Royal Navy 32 pounder cannon and 10- and 13-inch mortars, predominated in the exchange of fire with the Spanish garrison in El Morro.

By 17th July 1762, there were no Spanish guns in action on the north-east bastion of El Morro castle, with only two in action elsewhere and the British commanders considered it was possible to begin an approach to the fortifications.

Surrounding the main wall of El Morro Castle was a 70-foot-deep ditch and a ‘covered way’ or rampart on the outside of the ditch.

In preparation for the storming of El Morro Castle, the British built a line of breastworks, over a distance of 300 yards, from the British lines to a point on the cliff where the defensive ditch of El Morro Castle opened into the sea.

Once the British breastwork reached the covered way it was extended along the covered way, parallel to the main wall.

From this breastwork extension, guns, mortars and small arms were fired over a short range at the Spanish troops on the walls.

In building El Morro Castle in the 16th Century, the Spanish engineers had cut the 70-foot ditch that surrounded the main wall straight into the rock. A narrow ridge was left to prevent sea water from entering the ditch.

When the breastwork reached the covered way, the British engineers discovered this ridge and used it to cross the ditch and begin mining directly under the north-east bastion of the castle.

In the early hours of 22nd July 1762, the Spanish carried out sorties to capture and destroy the British batteries, breastworks and mining operations.

1,300 Spanish seamen, militia and regular soldiers made three separate attacks.

The first attack was by a Spanish force that crossed the harbour entrance in boats and climbed onto the high ground between El Morro Castle and La Cabaña heights.

This force was held by a piquet of 30 British soldiers and then driven back to their boats by the 3rd Battalion of the 60th Royal Americans.

The second attack was against the mining operations at the north-east corner of El Morro Castle. This attack was driven back.

In the third attack, the Spanish landed from the harbour at the foot of La Cabaña, further to the south. This attack was also driven back to its boats.

Casualties on each side were low and no major damage was caused to the British siege works.

The Spanish now moved naval ships across the harbour and attempted a bombardment of the British batteries, which opened a heavy return fire.

The consequence was severe damage to the Spanish ships and the loss of the Spanish frigate Perla, before the Spanish ships withdrew across the harbour.

At the end of July 1762, 3,188 British regular and American provincial troops, sent by General Amherst, arrived from America, providing a welcome reinforcement of healthy soldiers for Albemarle’s army.

Storming of El Morro Castle:

The British mines under El Morro were ready to be fired by 29th July 1762 and the troops in place to storm the Castle.

Albemarle decided to carry out a bluffing operation to try and panic the Spanish into abandoning El Morro.

Guns were fired and signals flown as if to herald an assault, but the Spanish made no move to abandon El Morro.

The actual assault took place the next day, 30th July 1762.

In an attempted spoiling attack, Spanish boats sailed around the headland and fired on the British troops and engineers in the castle ditch. They were driven off.

The British ship Alcide and a number of armed boats were stationed off El Morro to prevent any further interference from the sea.

Commodore Keppel wanted Royal Navy seamen to take part in the assault, but his older brother, Lord Albemarle, directed that only soldiers were to form the storming party.

There were two British mines to be fired; one under the outer bank or counterscarp of the 70-foot ditch, the other under the wall of the north-west bastion of El Morro Castle.

The mines were fired at 2pm on 30th July 1762, while the attacking party waited to make the assault.

The mine under the counterscarp failed to knock sufficient rubble into the ditch to make it possible to cross, but the second mine severely damaged the wall of the bastion which could be reached by way of the narrow ridge.

There was a hurried conference in the entrenchments and it was decided to launch the assault.

The British storming party comprised 281 infantry (102 men from the 1st Royals, 129 Marksmen from various regiments and 50 men from the 90th Regiment) with 150 men of the 35th Regiment in reserve; all commanded by Lieutenant Colonel James Stuart of the 90th Regiment.

The attackers clambered across the narrow ridge and rushed into the west bastion before the Spanish defenders could recover from the explosion.

After 30 minutes of hand to hand fighting El Morro Castle was taken, the Spanish commander, Captain Don Luis de Velasco being mortally wounded.

British casualties in the storming of El Morro Castle were 14 killed and 28 wounded.

The Spanish garrison of El Morro Castle at the time of the storming of the castle comprised 7 senior officers, 298 regular infantry, 304 marines and seamen and 94 black African slaves and freed slaves. Of this garrison, the commander, Don Luis de Velasco and his deputy, Colonel Marques Gonzales and 130 men were killed defending the castle, 213 drowned or were killed in their boats escaping from the castle and 326 were captured.

Following the fall of El Morro Castle, the British built further batteries on the Cabaña heights and extended their works along the coast from Chorera, with batteries directed at the fort of La Punta and at the north and west walls of the city.

A heavy bombardment of the city began at dawn on 11th August 1762.

The Spanish guns were quickly overwhelmed and the fort at La Punta abandoned by its garrison.

By 2pm on that day, Governor Prado concluded that further resistance was hopeless and Spanish officers were sent to the British lines under a flag of truce, seeking terms for the surrender of the city.

A 24-hour truce was agreed to permit negotiations to take place between Prado and the British commanders. However, no agreement was reached.

The sticking point was the refusal of the Spanish to include their warships in the surrender of the city and the insistence of the British that they do.

On 12th August 1762, Albemarle sent a message to Prado threatening a resumption of the British bombardment. Prado considered he had no choice but to surrender on the British terms, which he did.

Under the terms of capitulation, the Spanish surrendered to the British the city of Havana and its environs, all military equipment, public records, merchant ships and warships in Havana harbour, public moneys and city warehouses with their contents.

On 14th August 1762, British troops occupied the fort at La Punta and entered the city through La Punta Gate and the Land Gate, relieving the Spanish guards and taking possession of the City of Havana.

On 21st August 1762, the British fleet entered Havana Harbour and took control of the Spanish ships in the harbour, including around 100 merchant ships.

9 Spanish warships surrendered to the British under the capitulation of Havana, with 3 sunk behind the boom and 2 newly built ships set on fire by the Spanish.

The Spanish warships surrendered to the British under the capitulation of Havana were:

Tigre 70 guns, Marquis del Real Transporte and Don Juan Ignacio Madariaga

Reyna 70 guns, Don Luis Vicente de Velasco

Soverano 70 guns, Don Juan Garcia del Postigo

Infante 70 guns, Don Francisco de Medina

Neptuno 70 guns*, Don Pedro Bermudez

Aquilon 70 guns, Don Vicente Gonzales Bassecourt

Asia 64 guns*, Don Francisco Garganta

America 60 guns, Don Juan Antonio de la Colina

Europa 60 guns*, Don Jose Diaz de San Vicente

Conquestado 60 guns, Don Pedro Castejon

San Genaro 60 guns new ship, burnt by the Spanish

San Antonio 60 guns new ship, burnt by the Spanish

Frigates:

Vinganaza 24 guns

Thetis 24 guns

Marte 18 guns

* Ship sunk by the Spanish behind the boom at the entrance to Havana Harbour.

Casualties at the Capture of Havana:

Between 7th June and 9th October 1762, Pocock’s fleet lost 800 seamen and 500 marines killed, most by disease. Only 86 were killed in action.

On 9th October 1762, 2,673 seamen and 601 marines were sick, with few expected to recover.

Between 7th June and 18th October 1762, British Army casualties were 5,366 soldiers killed, 4,708 of them by disease.

A large number of soldiers were sick at the end of the campaign. These were taken to New York, where few recovered.

New Yorkers were horrified at the state of the sick soldiers.

British army operations in America were substantially hampered for some time by the loss of so many soldiers.

Pocock was forced to report to the Admiralty that his squadron was incapable of undertaking further operations.

The intended attack on French Louisiana was abandoned.

Spanish casualties in the Capture of Havana are unknown.

Follow-up to the Capture of Havana:

On the return of the Spanish garrison to Spain, the King ordered an enquiry into the conduct of Prado, the Governor of Havana and a number of military and civilian officials considered responsible for the loss of the city and the naval squadron.

The enquiry, in the nature of a court-martial, condemned Prado to death and gave prison sentences to other officials.

Prado’s sentence was commuted to a period of imprisonment and he died in prison.

The capture of Havana and the Spanish naval and maritime fleets realised a substantial sum of money for distribution as prize money to the British force.

This distribution was far from equitable and gave rise to years of dispute.

The primary recipients were the senior officers. It is said that the fortunes of the Albemarle family (Lord Albemarle, Major General William Keppel and Commodore Augustus Keppel) were made.

Admiral Pocock received a similar amount to Lord Albemarle.

Lieutenant General George Eliott bought Heathfield House with his share of the prize money. He went on to make his name as the Governor of Gibraltar during the ‘Great Siege’ from 1779 to 1783.

Following the capture of Havana, Lord Albemarle became the governor of the city until it was returned to Spain by the terms of the Peace of Paris, in exchange for Florida.

Captain Luis Vicente de Velasco:

Captain Luis Vicente de Velasco, captain of the Spanish warship Reina, was appointed commander of the garrison in El Morro Castle at the beginning of the British attack.

Velasco excited the admiration of British and Spanish by his resourceful and determined defence of El Morro.

When the British stormed El Morro on 30th July 1762, Velasco and his deputy, Marques Gonzales fought hard to maintain the castle, the garrison only giving way with Gonzales killed and Velasco mortally wounded.

British surgeons treated Velasco, but he died the next day, being buried in Havana with full military honours.

In the disgrace of the surrender of Spain’s principal colonial port and the capture of so many warships, the conduct of the defence of El Morro Castle was considered the one redeeming trait.

King Charles III of Spain raised a statue of Velasco in his home town, Meruelo, and made his son the Marquis of Velasco.

A coin showing the heads of Velasco and Gonzales was issued by the Madrid Academy of Arts in 1763.

Velasco’s ship Reyna, captured in Havana harbour with the Spanish surrender, was taken into the Royal Navy as HMS Reyna.

Comment on the form of attack:

Historians venture onto dangerous ground in criticising the form of a military operation.

A repeated criticism of the Havana operation is that the British should have attacked the city directly, without first capturing El Morro Castle, thereby saving, it is said, British lives and a great deal of time.

The assessment of the Havana defences and analysis of the best method of attack was drafted by the chief engineer of the expedition, Lieutenant Colonel Patrick McKellar.

Syrett describes this memorandum as ‘able, if unimaginative’.

In fact McKellar’s memorandum was a matter of fact assessment of the defences of the city and a firm recommendation that El Morro Castle had to be captured before any direct assault could be risked on Havana itself.

Otherwise, a direct assault would be subjected to heavy flanking fire from the Spanish warships in the harbour on the right and El Morro Castle and La Punta on the left.

A major consideration was the size of the garrison.

The builder of the original defences of Havana, Giovanni Battista Antonelli, was of the view that the taking of La Cabana Heights was the key to the capture of the city.

Anecdotes and traditions from the Capture of Havana:

- On 28th July 1762, Colonel McKellar noted in his journal that lightning struck a large Spanish merchant ship in the harbour. The ship caught fire and blew up within 10 minutes.

- Dominic Serres the Elder, a celebrated naval artist, painted a number of pictures of scenes from the Capture of Havana in 1762. Serres, a Frenchman, started life as a sea officer. Captured by a British ship, Serres settled in England and took to painting seascapes. Many of Serres’ Havana pictures were taken from a series of prints published by an officer of the expedition, although Serres will have drawn on his own experiences of Havana when a sea captain.

References for the Capture of Havana:

History of the British Army Volume II by John Fortescue

The Royal Navy, A History Volume III by Clowes

The Siege and Capture of Havana 1762 edited by David Syrett

The previous battle of the Seven Years War is the Capture of Manila

The next battle in the British Battles sequence is the Siege of Arcot