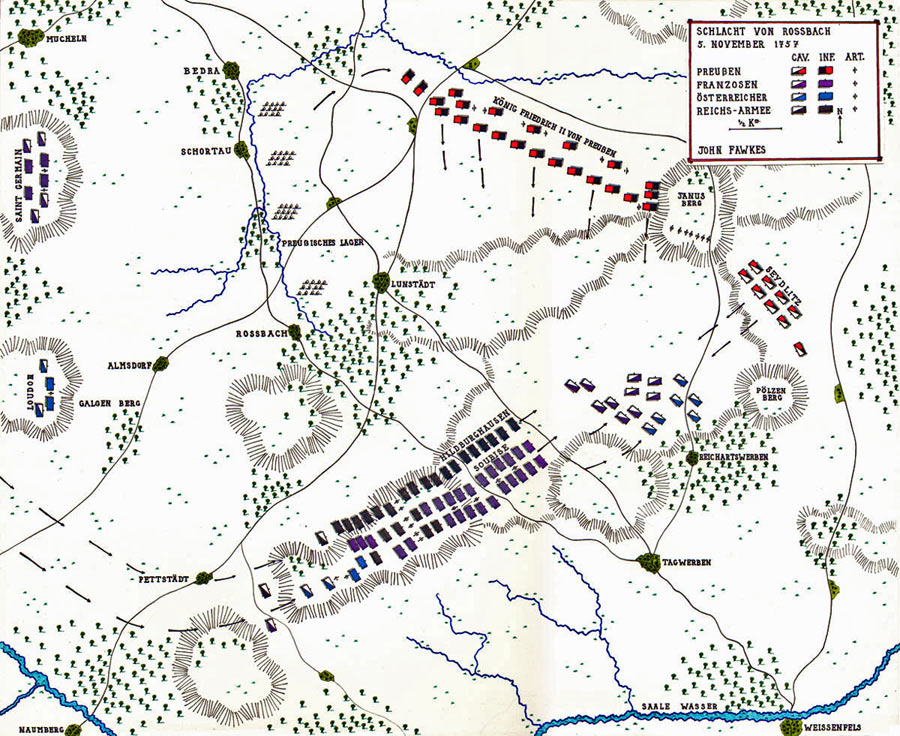

Frederick the Great’s victory on 5th November 1757, over the French army of Prince Soubise and the Reichsarmée

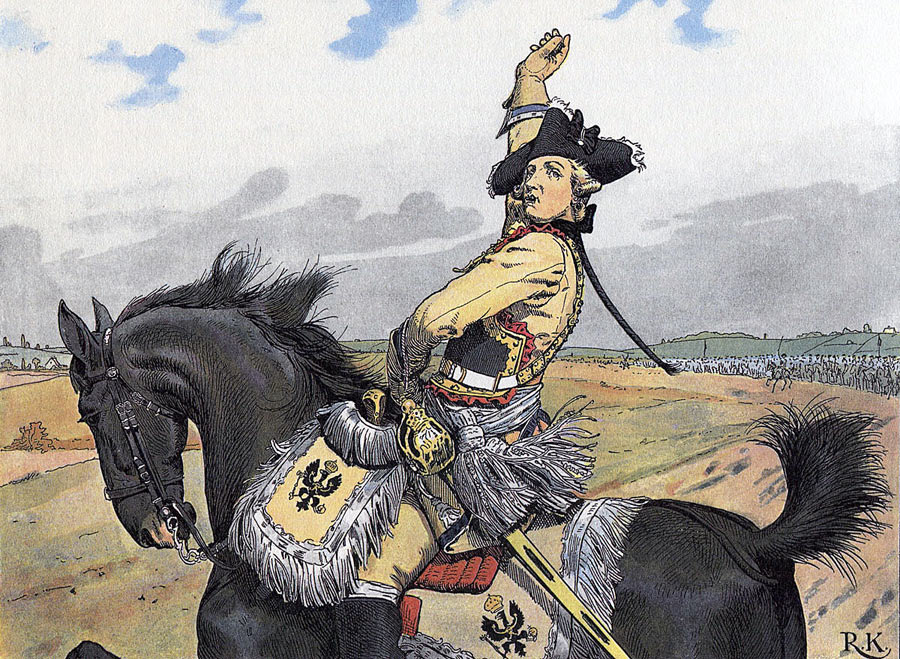

Major General von Seydlitz throws his pipe in the air as he leads his Prussian cavalry to the attack at the Battle of Rossbach on 5th November 1757 in the Seven Years War: picture by Richard Knötel

The previous battle in the Seven Years War is the Battle of Kolin

The next battle in the Seven Years War is the Battle of Leuthen

Battle: Rossbach

Date of the Battle of Rossbach: 5th November 1757.

Place of the Battle of Rossbach: In the West of Saxony.

War: The Seven Years War.

Contestants at the Battle of Rossbach: Prussians against an army comprising mainly French troops and the Reichsarmée with a contingent of Austrians.

Generals: King Frederick II of Prussia commanding the Prussian Army against the French general Prince Soubise commanding the joint army of the French and the Reichsarmée. The Reichsarmée was commanded by the Austrian Field Marshal Prince Joseph Friedrich von Sachsen-Hildburghausen.

Size of the Armies at the Battle of Rossbach: Prussians: 16,600 infantry, 5,400 cavalry and 79 guns. French: 30,200 troops and 60 guns. Reichsarmée (including the Austrians): 10,900 troops and 45 guns.

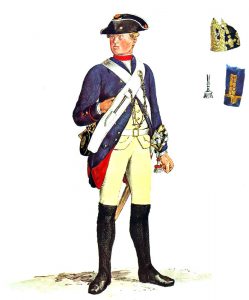

Winner of the Battle of Rossbach: The Prussians decisively.

Uniforms and equipment at the Battle of Rossbach: The Prussian infantry and artillery wore a dark blue coat turned back at the lapels, cuffs and skirts, with britches and black thigh length gaiters. Each soldier carried on a cross belt an ammunition pouch, bayonet and ‘hanger’ or small sword. Headgear for the line companies was the tricorne hat, with a flattened front corner, bound with white lace. Grenadiers wore the distinctive mitre cap with a brass plate at the front. Fusilier infantry regiments and artillery wore a smaller version of the grenadier cap.

Prussian Regiment Gensdarmes

No 10: picture by Adolph Menzel

as part of his series of pictures

‘Die Armee Friedrichs des Grossen in ihrer Uniformierung’

The infantry carried a musket as the main weapon. This single shot firearm could be loaded and fired by a well trained soldier around 3 to 4 times a minute. As an early improvement Frederick introduced the iron ramrod and then the reversible ramrod (the soldier did not have to worry whether he had the ramrod the right way round) which increased the rate of fire of his infantry, the old wooden ramrod being liable to break in the stress of battle.

The Prussian infantry regiment was based on the cantonment with soldiers joining their local regiment. In peacetime soldiers were released for key agricultural times, sowing and harvesting. In the autumn, reviews were conducted of all regiments to check they were up to the required standard. Each year regiments were selected to undergo review at Potsdam under the eye of the King. Officers whose soldiers’ performance was considered by Frederick to be substandard were subject to a public tongue lashing and in extreme cases dismissal on the spot.

The efficiency of the Prussian regiments at drill enabled them to move about the battlefield with a speed and manoeuvrability that no other European Army could equal. The Battle of Rossbach is a striking example of this facility.

Prussian Infantry Regiment von

Quadt No 9: picture by Adolph

Menzel as part of his series of

pictures ‘Die Armee Friedrichs

des Grossen in ihrer Uniformierung’

Heavy cavalry of the period comprised cuirassiers and dragoons. The Prussian cuirassiers wore a white coat, steel cuirass, white britches and thigh boots. Prussian Dragoons wore a light blue coat. The headgear was a tricorne hat. Weapons were a heavy cavalry sword and single shot flintlock carbine.

The light cavalry arm was provided by the Prussian Hussar regiments. The true hussars were Hungarians in the Austrian service. The hussars of other armies were given the same dress as the original hussars and required to perform a similar light cavalry role of reconnaissance and harassing the enemy’s outposts and supply columns.

Following the Battle of Mollwitz and in particular after the First Silesian War the Prussian Hussars were re-organised and re-trained to provide an efficient scouting and light cavalry service. Frederick found in Colonel von Zieten the ideal officer to implement the improvements in the hussar regiments. The Prussian Hussars wore the traditional hussar dress of tunic, britches, dolman (slung jacket), busby (fur hat) with bag, sabretache (leather wallet on straps hanging from the belt) and curved sword.

Unlike the original Hungarian Hussars of the time who were considered to be little more than indisciplined freebooters the Prussian Hussars were well able to take a position in the cavalry line and perform valuable service in battle, as at the Battle of Hohenfriedburg and on other occasions.

Prussian Grenadier-Garde von

Retzow No 6: picture by Adolph

Menzel as part of his series of

pictures ‘Die Armee Friedrichs

des Grossen in ihrer Uniformierung’

The French infantry regiments in the main wore white coats and tricorne hats. The grenadiers wore bearskin caps. The French army contained regiments of various nationalities, Swiss, Irish, German, Netherlanders and Hungarians. Swiss and Irish regiments wore red coats. Some foreign regiments wore blue coats.

The French cavalry wore coats of a variety of colours.

The Reichsarmée comprised contingents from a range of small German states. Several were Protestant states whose regiments were more sympathetic to the Prussians than to the French who were seen as invaders in Germany. These various contingents wore a variety of uniforms based on the general pattern for the larger armies.

The Austrian infantry wore white coats with lapels, cuffs and skirts turned back showing the regimental lining colour. Headgear was the tricorne hat for line infantry and bearskin cap for grenadiers. The infantry weapons were musket, bayonet and hanger small sword. Heavy cavalry wore white coats and hats as for the infantry and were armed with a heavy sword and carbine. Some dragoons wore a bearskin cap. The Austrian army contained a large number of irregular units notably the Pandours from the Balkans who wore their ethnic dress without uniformity. Hungarian Hussars provided the light cavalry arm. These Hussars, dressed as described for the Prussian Hussars, were considered to be little more than bandits but were highly effective in all the roles required of light cavalry.

Prussian artillery: picture by Adolph

Menzel as part of his series of pictures

‘Die Armee Friedrichs des Grossen

in ihrer Uniformierung’

The artillery of each army was equipped with a range of muzzle loading guns. The problem with artillery of the time was that it adopted a position for battle and was then unable to move to react to a changing tactical situation.

Frederick implemented significant improvements to the Prussian Army between the two Silesian wars. The eleven years of peace before the Seven Years War enabled Frederick to bring the various arms of the Prussian service to a high pitch of efficiency. Each year the regiments were subjected to a training cycle that culminated in reviews at Potsdam under the King’s exacting eye. Autumn manoeuvres were held in Silesia, the area where much of the expected warfare would be conducted (see the benefit of these manoeuvres at the Battle of Leuthen).

The Prussian infantry was a tested and established asset and required little improvement. Most of the innovation was targeted at the cavalry, artillery and technical arms.

One unfortunate development from the Silesian Wars was that Frederick formed the view that his infantry could win their battles simply by the steadiness of their advance. The Seven Years War began with the Prussian infantry doctrine being to advance with muskets at the shoulder and not to pause to fire on the enemy. The Battle of Prague showed this doctrine to be badly misguided and it was abandoned after causing the Prussians substantial casualties.

The Prussian infantry was soon trained to advance making brief halts to fire and reload, enabling it to deliver successive volleys as it marched up to the opposing army, a technique used to devastating effect at the Battle of Rossbach.

During the course of the Seven Years War Frederick extensively re-organised the artillery. New equipment was introduced, the guns standardised and the artillery formations overhauled. Frederick introduced horse artillery that could move around the battlefield.

Prussian Cuirassiers and Dragoons: Battle of Rossbach on 5th November 1757 in the Seven Years War: print by Menzel

Frederick brought the Prussian cavalry to a level of effectiveness unrivalled by any other European Army of any period. The basic requirement was a high standard of horsemanship in every soldier. A trooper was required to ride his horse every day, an exacting obligation in peacetime. Contrast this with the practice of the British regiments of horse and dragoons of the time, in which as a measure of economy the horses had their shoes struck off and were put out to grass unridden for the whole of the summer (see Viscount Molesworth’s standing orders for his dragoon regiment).

Every year Frederick exercised the cavalry during the autumn manoeuvres. Frederick required the cuirassier and dragoon regiments to form line at the gallop and deliver a charge, with the troopers so close that they rode knee behind knee with the horses touching. Frederick developed the capability of the cavalry year by year. Finally he required his mounted regiments to be able to deliver three such charges one after the other at full gallop.

Prussian Husaren-Regiment von

Seydlitz No 8: picture by Adolph

Menzel as part of his series of

pictures ‘Die Armee Friedrichs des

Grossen in ihrer Uniformierung’

The effect of this exacting training was graphically illustrated by the performance of the Prussian cavalry force led by General von Seydlitz against the Russians at the Battle of Zorndorf on 25th August 1758. Seydlitz’s squadrons crossed the Zabern-Grun stream, climbed the steep far bank and moved through an area of scrub, before forming two lines of hundreds of troopers at the gallop, so close together that the horses were touching, and delivering a devastating charge at full gallop against unshaken Russian infantry, who were overwhelmed. Against cavalry of this quality it mattered little whether the infantry was in line or square.

This extraordinary ability contrasted with most other European cavalry regiments which would form for the charge at the halt and then attack in a loose formation which would be lost in the course of the charge, ending with the horses blown and all cohesion gone. If the infantry under attack seemed unduly aggressive, the attacking cavalry would be liable to swerve around them or pull up.

It was Frederick’s order that any Prussian cavalry commander receiving a charge at the halt would be tried by court-martial. Commanders had the discretion to attack if they considered that a favourable opportunity existed, without waiting for orders.

The Battle of Rossbach is probably the best example of the quality of the Prussian heavy cavalry and its ability to deliver battle winning charges.

Account of the Battle of Rossbach:

Following his disastrous defeat at the Battle of Kolin on 18th June 1757 in central Bohemia Frederick the Great withdrew his army from besieging Prague and fell back to Leitmeritz in northern Bohemia. A Prussian army commanded by Frederick’s brother, Prince August William, covered the ground to the East of the Elbe River.

The Prussian defeat was the signal for the countries allied against them to go on the offensive. The Russians moved into East Prussia and an army commanded by Prince Soubise comprising French regiments and the Reichsarmée moved into Western Saxony.

General Freidrich Wilhelm von Seydlitz, the commander of the Prussian cavalry at the Battle of Rossbach 5th November 1757

Frederick marched to meet Prince Soubise with a Prussian army of some 25,000 troops, half the size of the army he was moving to intercept.

Following his conduct at the Battle of Kolin Frederick Wilhelm von Seydlitz was promoted Major General and awarded the Pour le Mérite. Seydlitz commanded the Prussian cavalry in the Rossbach campaign.

On 15th September 1757 Frederick’s army entered the West Saxon town of Gotha. The Prussian army marched out the next day and a force of some 10,000 French troops occupied the town. Seydlitz returned with a small force and ‘planted’ information that the Prussian army was nearby at which the French force hastily evacuated Gotha.

The French left a quantity of unmilitary booty for the Prussians to loot including cooks, clerks, whores, parrots, perfumes and women’s clothes. The Prussian army was hugely amused. Frederick however had other concerns: his troops had been defeated in East Prussia by the Russians at Gross-Jägersdorf, Russian and Austrian forces were converging in a raid on Berlin, his trusted confidant General Winterfeldt, had been killed in a skirmish with the Austrians at Moys in Eastern Saxony and the army fighting to keep the French under the Duc de Richelieu out of Hanover had capitulated at Kloster-Zeven.

Prussian Hussars looting the French baggage at Gotha before the Battle of Rossbach 5th November 1757: picture by Richard Knötel

Frederick returned to Saxony to supervise the relief of Berlin. In late October 1757 Frederick received the news that the Reichsarmée had ventured east of the Saale River and was within striking distance.

By 28th October 1757 Frederick concentrated his army at Leipzig to strike at the Reichsarmée. A force under Duke Ferdinand of Brunswick marched from Magdeburg and Prince Moritz brought his corps from Berlin.

The Prussian troops were in a state of high morale and eager to be led against the Reichsarmée and the invading French troops of Prince Soubise.

Frederick’s army reached Weissenfels on the Saale on 31st October 1757 to see the French escaping across the river, burning the bridge in their rear.

On 3rd November 1757 Frederick crossed the Saale downstream from the town by a bridge of boats and later in the day reunited with the detached forces of Prince Moritz and Field Marshal Keith who had crossed the Saale above Weissenfels. The Prussian army came up with the French troops and the Reichsarmée in camp near Mϋcheln.

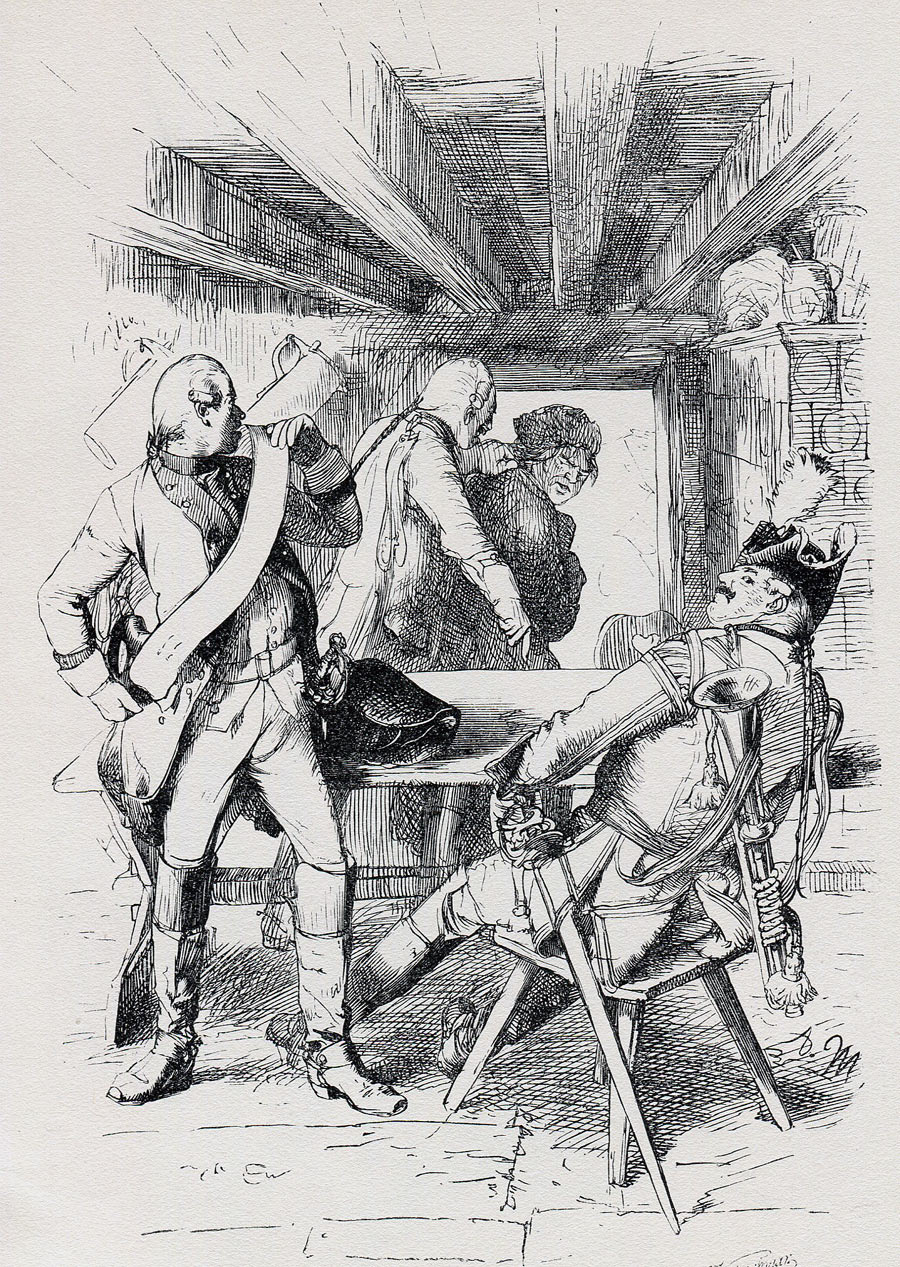

King Frederick II of Prussia watches the advancing enemy from the attic of the inn in Rossbach at the Battle of Rossbach 5th November 1757 in the Seven Years War

Frederick rode forward to reconnoitre the positions of the French and the Reichsarmée. He found a combined army of some 41,000, although rumour gave it a size of 60,000. Frederick’s army comprised 21,000 or nearly half the size of the force it faced.

The Prussians took up position and encamped between the village of Bedra and Rossbach, where Frederick established his headquarters. The innumerable musicians in the French camp could be heard playing in celebration at the apparent Prussian recoil. But Frederick was biding his time in the knowledge that the French and the Reichsarmée were in trouble with their supplies running low.

At daybreak on 5th November 1757 the preponderance of the French army and the Reichsarmée prepared to launch an assault. Patrols from the Prussian free battalions watched as Soubise’s regiments formed into three unwieldy columns facing south, shielded by the corps of Saint Germaine whose troops held the heights around Schortau.

The three columns set off in a cumbrous march intended to take them in a wide arc around the southern end of the Prussian position.

It says much of the ignorance and complacency of the French commander Prince Soubise that he could have thought it possible to execute this clumsy manoeuvre in the presence of such an aggressive and decisive field commander as Frederick and the highly trained and swift moving Prussian army.

It was an extraordinary spectacle. The French army was incapable of silent movement. Its drill was far from competent. The further the army marched the more spread out the regiments became. Bands played and soldiers gossiped in excitement.

At Rossbach Frederick’s Capitaine des Guides Friederich Gaudi observed the hostile army from the attic of the inn that did duty as the Prussian headquarters. Frederick took some persuading that Soubise was executing such an extraordinary move. Once convinced and his orders given the Prussian army was on the march in minutes. The tents of the encampment disappeared as if struck down.

The first move was by the Prussian cavalry. On Frederick’s direction Seydlitz took his regiments of cuirassiers and dragoons in a circular move around the back of the Janus Hill which lay to the rear of the Prussian camp. The Prussian infantry followed heading more directly for Janus Hill. Colonel Moller hastened with a strong battery of canon to the top of the hill.

The attack of the Prussian cavalry under Major General von Seydlitz at the Battle of Rossbach 5th November 1757

As the Prussian move was straight to their rear, so far as it could be seen, it was assumed by the French and the Reichsarmée that Frederick was in full retreat. The advance guard of Austrian, French and Reichsarmée cavalry hastened to intercept the Prussian escape.

At 3.15pm Colonel Moller’s canon opened fire from the top of the Janus Hill. On this signal Seydlitz ordered the charge and his cavalry swept over the brown of the rise that had concealed them from the advancing Austrians and French.

Charge of the Prussian cuirassiers led by Major General von Seydlitz at the Battle of Rossbach 5th November 1757 in the Seven Years War

The impact of the Prussian attack was devastating, falling on the Austrian cuirassier regiments of Bretlach and Trautmansdorff and the Szecheny Hussars and regiments of Imperial German Horse. These regiments had only sufficient time to change from column into line before receiving the Prussian charge. French cavalry came up in support, but the whole mass was swept back when Seydlitz launched his second line of regiments into the attack.

With his regiments well in hand Seydlitz brought his troopers to a halt to await the next opportunity to charge. He wheeled the regiments to the left and took position in the woods behind the hill over which the allied infantry were advancing.

Between the Janus Hill, from which Colonel Moller’s guns were firing with great effect, and the line of their camp, the Prussian infantry were turning to their right and coming forward in line to attack the unwieldy columns of the French and the Reichsarmée. The leading Prussian regiments, Kleist (9) and Alt-Braunschweig (5) fired devastating volleys into the leading French regiments of Piémont and Mailly.

The French and the Reichsarmée were severely hampered by being crowded into columns, an inappropriate formation for battle. Under the heavy Prussian fire the columns quickly dissolved into an uncontrollable mass. At this point Seydlitz launched his second charge into the right flank of the columns.

The effect of the combined attacks of the Prussian infantry and cavalry and the bombardment from Moller’s guns brought about a complete collapse in the columns and the French, Austrian and Reichsarmée troops turned and fled the field or surrendered.

A French witness described what then occurred: “Everybody sank into a mob. It was not possible to prevent the flight. The Prussian infantry followed on our heels and fired without checking its advance or having a man drop out of rank or file. The artillery bombarded us without pause.”

The dissolving army poured back past Pettstädt where the detached forces of Saint-Germain’s French light infantry and Loudon’s Austrians came down from their positions to the West of Rossbach to cover the frenzied flight.

By 5pm darkness had fallen. Frederick made his way to Schloss Burgwerben where he intended to spend the night but found the castle full of wounded French officers. He moved into a nearby house.

Casualties at the Battle of Rossbach: The Prussian casualties were 548. The French lost 6,600 killed, wounded and prisoners. The Reichsarmée lost 3,552 killed, wounded and prisoners.

Aftermath to the Battle of Rossbach: Frederick the Great considered the Battle of Rossbach to be a vindication of his army and his leadership after the disaster of Kolin. He hastened back to Silesia to inflict the defeat of Leuthen on the Austrians in December 1757.

Anecdotes from the Battle of Rossbach:

- The defeat at Rossbach was a major blow to the prestige of the King of France and is considered a contributory factor to the decline in the prestige of the French Monarchy and indirectly to the French Revolution in 1789.

- The French made a point of describing their defeat of Prussia at Jena and Auerstädt in 1806 as being in revenge for Rossbach. After the battles French troops destroyed the Prussian memorial to Rossbach on the battlefield.

- After the battle Prussian Hussars ransacked the French baggage and came away with many exotic and unmilitary trophies (see the illustration above of Prussian Hussars looting women’s clothing).

- The French Foreign Minister said of Frederick “We must not forget that we are dealing with a prince who is at once his own commander in the field, chief minister, logistical organiser and, when necessary, provost-marshal. These advantages outweigh all our badly executed and badly combined expedients.”

- The victory of Rossbach caused King George II of England to repudiate the convention of Kloster-Zevern and re-enter the war on the Prussian side, with the assistance of Prince Ferdinand of Brunswick, despatched by Frederick to command the British, Hanoverian and other protestant forces in Western Germany.

References for the Battle of Rossbach:

Frederick the Great by Thomas Carlile

Frederick the Great by Christopher Duffy

The Army of Frederick the Great by Christopher Duffy

The Army of Maria Theresa by Christopher Duffy

The previous battle in the Seven Years War is the Battle of Kolin

The next battle in the Seven Years War is the Battle of Leuthen