Frederick the Great’s second victory over the Austrians

in the Seven Year War in a confused and expensive battle

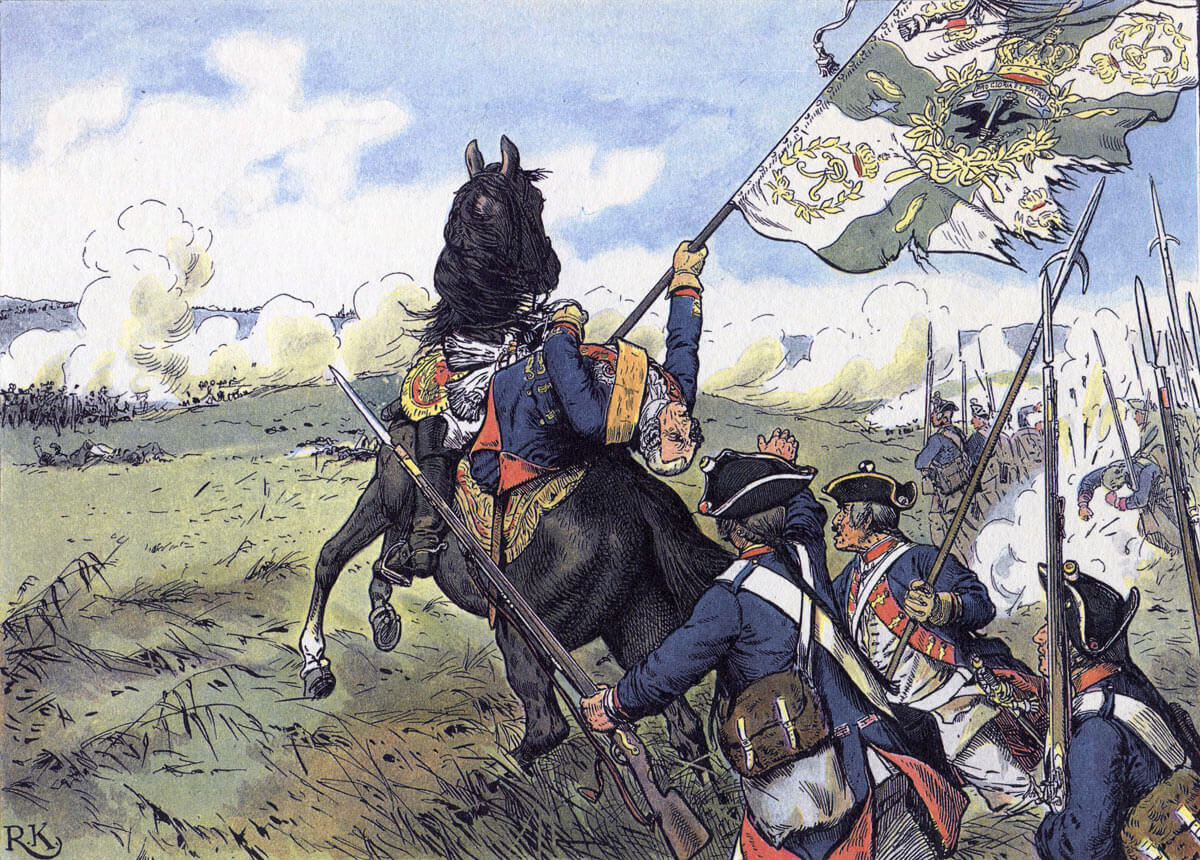

Field Marshal Schwerin, killed while leading his own regiment into the attack at the Battle of Prague, 6th May 1757 in the Seven Years War, after seizing the regimental colours: picture by Richard Knötel

The previous battle in the Seven Years War is the Battle of Lobositz

The next battle in the Seven Years War is the Battle of Kolin

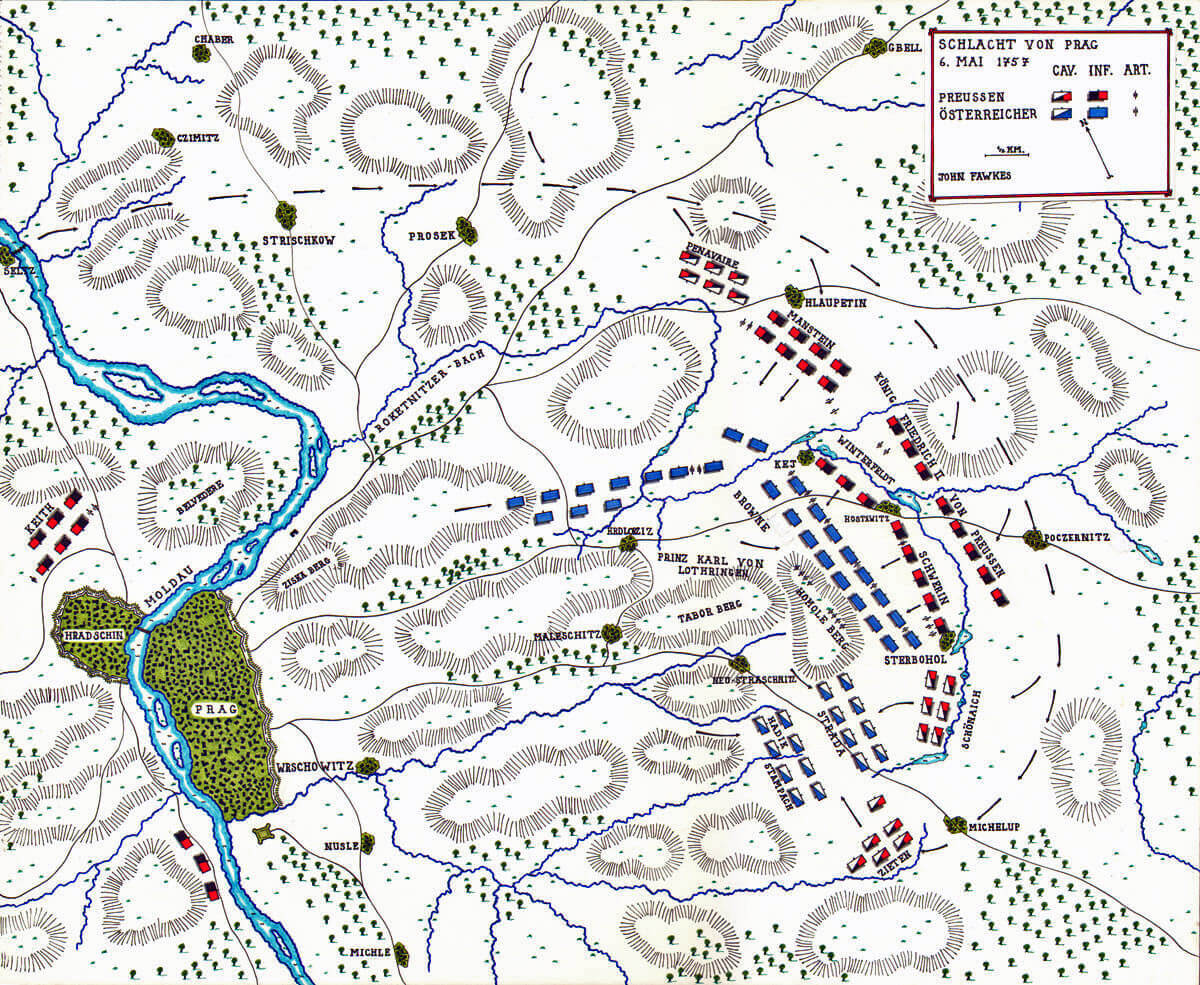

Battle: Prague

Date of the Battle of Prague: 6th May 1757.

Place of the Battle of Prague: In Central Bohemia, Prague being the capital city of Bohemia.

War: The Seven Years War.

Contestants at the Battle of Prague: Prussians against an Imperial Austrian Army comprising the various nationalities that made up the Austro-Hungarian Empire (Austrians, Hungarians, Bohemians, Silesians, Croats, Italians and Moravians).

Generals at the Battle of Prague: King Frederick II of Prussia, assisted by Field Marshal Schwerin, commanding the Prussian Army against Prince Charles of Lorraine, brother-in-law of Empress Marie Theresa, and Field Marshal Browne commanding the Austrian Army.

Size of the Armies at the Battle of Prague: 65,000 Prussians (47,000 infantry, 17,000 cavalry) and 214 guns against 62,000 Austrians (48,500 infantry, 12,600 cavalry) and 177 guns.

Winner of the Battle of Prague: The Prussians under Frederick the Great, but at great cost.

Prussian Dragoner-Regiment von

Oertzen No 4: Battle of Prague, 6th May 1757 in the Seven Years War: picture by Adolph Menzel

Uniforms and equipment at the Battle of Prague: The Prussian infantry and artillery wore a dark blue coat turned back at the lapels, cuffs and skirts, with britches and black thigh length gaiters. Each soldier carried on a cross belt an ammunition pouch, bayonet and ‘hanger’ or small sword. Headgear for the line companies was the tricorne hat, with a flattened front corner, bound with white lace. Grenadiers wore the distinctive mitre cap with a brass plate at the front. Fusilier infantry regiments and artillery wore a smaller version of the grenadier cap.

The infantry carried a musket as the main weapon. This single shot firearm could be loaded and fired by a well trained soldier around 3 to 4 times a minute. As an early improvement Frederick introduced the iron ramrod and then the reversible ramrod (the soldier did not have to worry whether he had the ramrod the right way round) which increased the rate of fire of his infantry, the old wooden ramrod being liable to break in the stress of battle.

Prussian Infantry Regiment Von Schwerin No 24 (the regiment lost 13 officers and 522 men in the battle): Battle of Prague, 6th May 1757 in the Seven Years War

The Prussian infantry regiment was based on the cantonment with soldiers joining their local regiment. In peacetime soldiers were released for key agricultural times, sowing and harvesting. In the autumn, reviews were conducted of all regiments to check they were up to the required standard. Each year regiments were selected to undergo review at Potsdam under the eye of the King. Officers whose soldiers’ performance was considered by Frederick to be substandard were subject to a public tongue lashing and in extreme cases dismissal on the spot.

The efficiency of the Prussian regiments at drill enabled them to move about the battlefield with a speed and manoeuvrability that no other European Army could equal. The Battle of Rossbach is a striking example of this facility.

Heavy cavalry of the period comprised cuirassiers and dragoons. The Prussian cuirassiers wore a white coat, steel cuirass, white britches and thigh boots. Prussian Dragoons wore a light blue coat. The headgear was a tricorne hat. Weapons were a heavy cavalry sword and single shot flintlock carbine.

Prussian Husaren-Regiment von Werner (the regiment captured 10 standards in the Battle of Prague) No 6: Battle of Prague, 6th May 1757 in the Seven Years War: picture by Adolph Menzel

The light cavalry arm was provided by the Prussian Hussar regiments. The true hussars were Hungarians in the Austrian service. The hussars of other armies were given the same dress as the original hussars and required to perform a similar light cavalry role of reconnaissance and harassing the enemy’s outposts and supply columns.

Following the Battle of Mollwitz and in particular after the First Silesian War the Prussian Hussars were re-organised and re-trained to provide an efficient scouting and light cavalry service. Frederick found in Colonel von Zieten the ideal officer to implement the improvements in the hussar regiments. The Prussian Hussars wore the traditional hussar dress of tunic, britches, dolman (slung jacket), busby (fur hat) with bag, sabretache (leather wallet on straps hanging from the belt) and curved sword.

Unlike the original Hungarian Hussars of the time who were considered to be little more than indisciplined freebooters the Prussian Hussars were well able to take a position in the cavalry line and perform valuable service in battle, as at the Battle of Hohenfriedburg and on other occasions.

The Austrian infantry wore white coats with lapels, cuffs and skirts turned back showing the regimental lining colour. Headgear was the tricorne hat for line infantry and bearskin cap for grenadiers. The infantry weapons were musket, bayonet and hanger small sword. Heavy cavalry wore white coats and hats as for the infantry and were armed with a heavy sword and carbine. Some dragoons wore a bearskin cap. The Austrian army contained a large number of irregular units notably the Pandours from the Balkans who wore their ethnic dress without uniformity. Hungarian Hussars provided the light cavalry arm. These Hussars, dressed as described for the Prussian Hussars, were considered to be little more than bandits but were highly effective in all the roles required of light cavalry.

Prussian Infantry Regiment von

Winterfeldt No 1 (the regiment lost 22 officers and 1,168 men in the battle): Battle of Prague, 6th May 1757 in the Seven Years War picture by Adolph Menzel

Following the humiliations of the First and Second Silesian Wars at the hands of Frederick the Great and his Prussian army the Austro-Hungarian authorities implemented wide ranging reforms of every branch of their army. Prince Joseph Wenzel von Liechtenstein after his experience of the devastating effectiveness of the massed Prussian artillery at the Battle of Chotusitz undertook a root and branch reform of the Austrian artillery, using his own fortune to fund the changes. The Austrian artillery that entered the Seven Years War was considered more effective than its Prussian counterpart.

Frederick implemented significant improvements to the Prussian Army between the two Silesian wars. The eleven years of peace before the Seven Years War enabled Frederick to bring the various arms of the Prussian service to a further high pitch of efficiency. Each year the regiments were subjected to a training cycle that culminated in reviews at Potsdam under the King’s exacting eye. Autumn manoeuvres were held in Silesia, the area where much of the expected warfare would be conducted (see the benefit of these manoeuvres at the Battle of Leuthen).

Prussian Infantry Regiment von Itzenplitz No 13: Battle of Prague, 6th May 1757 in the Seven Years Warpicture by Adolph Menzel

The Prussian infantry was a tested and established asset and required little improvement.

One unfortunate development from the Silesian Wars was that Frederick formed the view that his infantry could win their battles simply by the steadiness of their advance. The Seven Years War began with the Prussian infantry doctrine being to advance with muskets at the shoulder and not to pause to fire on the enemy. The Battle of Prague showed this doctrine to be badly misguided and it was abandoned after causing the Prussians substantial casualties.

The Prussian infantry was soon trained to advance making brief halts to fire and reload, enabling it to deliver successive volleys as it marched up to the opposing army, a technique used to devastating effect at the Battle of Rossbach.

During the course of the Seven Years War Frederick extensively re-organised the artillery. New equipment was introduced, the guns standardised and the artillery formations overhauled. Frederick introduced horse artillery that could move around the battlefield.

Prussian Füsilier-Regiment Markgraf Heinrich No 42: Battle of Prague, 6th May 1757 in the Seven Years Warpicture by Adolph Menzel

Frederick brought the Prussian cavalry to a level of effectiveness unrivalled by any other European Army of any period. The basic requirement was a high standard of horsemanship in every soldier. A trooper was required to ride his horse every day, an exacting obligation in peacetime. Contrast this with the practice of the British regiments of horse and dragoons of the time, in which as a measure of economy the horses had their shoes struck off and were put out to grass unridden for the whole of the summer (see Viscount Molesworth’s standing orders for his dragoon regiment).

Every year Frederick exercised the cavalry during the autumn manoeuvres. Frederick required the cuirassier and dragoon regiments to form line at the gallop and deliver a charge, with the troopers so close that they rode knee behind knee with the horses touching. Frederick developed the capability of the cavalry year by year. Finally he required his mounted regiments to be able to deliver three such charges one after the other at full gallop.

The effect of this exacting training was graphically illustrated by the performance of the Prussian cavalry force led by General von Seydlitz against the Russians at the Battle of Zorndorf on 25th August 1758. Seydlitz’s squadrons crossed the Zabern-Grun stream, climbed the steep far bank and moved through an area of scrub, before forming two lines of hundreds of troopers at the gallop, so close together that the horses were touching, and delivering a devastating charge at full gallop against unshaken Russian infantry, who were overwhelmed. Against cavalry of this quality it mattered little whether the infantry was in line or square.

This extraordinary ability contrasted with most other European cavalry regiments which would form for the charge at the halt and then attack in a loose formation which would be lost in the course of the charge, ending with the horses blown and all cohesion gone. If the infantry under attack seemed unduly aggressive, the attacking cavalry would be liable to swerve around them or pull up.

It was Frederick’s order that any Prussian cavalry commander receiving a charge at the halt would be tried by court-martial. Commanders had the discretion to attack if they considered that a favourable opportunity existed, without waiting for orders.

The Battle of Rossbach is another good example of the quality of the Prussian heavy cavalry and its ability to deliver battle winning charges through remaining under the tight control of its commander.

Background to the Battle of Prague:

The Second Silesian War ended with the Treaty of Dresden on Christmas Day 1745. The peace left King Frederick II of Prussia the master of Silesia and the Duchy of Gratz. In spite of the terms of the treaty Maria Theresa had agreed to, Frederick knew that the Austrian Empress would not rest until she had seized Silesia back from Prussian hands. The period between 1745 and the outbreak of the Seven Years War in 1756 was, in effect, only a truce. Austria and Prussia spent this period re-organising and building up their armies and manoeuvring for allies.

Field Marshal Kurt von Schwerin, Prussian commander killed at the Battle of Prague 6th May 1757 in the Seven Years War

In the Silesian Wars Prussia had been allied to France and the other long standing enemy of Austria, the Kingdom of Bavaria. Britain was the traditional enemy of France so King George II had committed Britain to an alliance with Austria. Hanover followed Britain with other Protestant German states and the Netherlands.

For the next and decisive round between Austria and Prussia, the Austrian Chancellor Kaunitz worked to establish an alliance with France. In the final year before the Seven Years War Frederick signed an alliance with Britain, achieving Kaunitz’ aim of pushing France into the arms of Austria. For the French the main enemy in the impending war would inevitably be Britain, with the British threat to the valuable French colony of Canada.

Kaunitz had further successes. The King of Poland, also the Elector of Saxony, committed himself to maintaining the alliance with Austria that had been so disastrous for Saxony in the Silesian Wars. The final coups were to bring into the Austrian camp the Empress Catherine of Russia and the Swedes with their threatening position in Swedish Pomerania to the North of Brandenburg. Frederick was to comment caustically “Are we at war with Sweden?” in view of Sweden’s inaction in support of the alliance.

General Karl von Winterfeld, Prussian commander killed at the Battle of Prague 6th May 1757 in the Seven Years War

Frederick did not wait for Prussia to be attacked. On 29th August 1756 he invaded Saxony, as a preparatory move to attacking Bohemia, intending to incorporate the Saxon army into his own. At the end of September 1756 Frederick took an army over the Bohemia border and fought the successful Battle of Lobositz. In spite of his defeat the Austrian commander Field Marshal Browne took a corps down the eastern bank of the Elbe in an attempt to rescue the Saxon Army besieged in the camp at Pirna, to the South of Dresden. Declining to withdraw into Bohemia with Browne’s force the Saxons surrendered to Frederick, who had returned to Dresden. The Saxon army was incorporated in the Prussian army.

It is generally accepted that by failing to press an invasion of Bohemia in 1756 with all his forces Frederick lost the opportunity to win the war against Austria before it could mobilise its forces fully and before France and Russia committed themselves to the war against Prussia.

That is what confronted Frederick at the beginning of 1757. Having satisfied himself that the French would not be a threat until later in the year Frederick launched the invasion of Bohemia he should have carried out the year before.

Prince Moritz advanced from Saxony with 19,300 troops. Frederick marched south by way of the valley of the Elbe with 39,600 troops. The Duke of Bevern advanced on Jung-Bunzlau with 20,300 troops while Field Marshal Schwerin moved south from Silesia and swung west to join Bevern with 34,000 troops.

Field Marshal Browne, the Austrian commander, was in early 1757 in the later stages of tuberculosis. The main Austrian force was encamped on the River Eger at Budin. The combined army of Frederick and Prince Moritz marched south at speed, crossing the Eger upstream of the Austrian camp and moving on to threaten Prague. In the meantime the eastern Prussia forces manoeuvred towards the West to join the King’s army.

Frederick arrived at the Jesuit house at Tuchomirschitz the night after it had been vacated by Browne and the newly arrived Austrian Supreme Commander Prince Charles of Lorraine. The inhabitants told Frederick how Prince Charles and Browne had nearly come to blows after a violent argument on how the Prussians were to be met.

The Prussians hurried on in the hope of bringing the Austrians to battle on the west bank of the Moldau but found that they had crossed the Moldau and taken up positions to the east of the city.

Account of the Battle of Prague:

Frederick reached Prague on 2nd May 1757. Schwerin and Bevern crossed the Elbe at Brandweis on 4th May.

On 5th May 1757 Frederick crossed the Moldau at Seltz, 4 miles downstream from Prague and joined with Schwerin. Field Marshal Keith had been left on the left bank of the Moldau with 32,000 troops. Frederick with the combined army on the right bank commanded 65,000 troops. The Austrian army before them comprised 62,000 troops.

Frederick’s army was on the march east from the Moldau at 5am on 6th May 1757. An hour later in accordance with the King’s command Schwerin’s and Winterfeldt’s troops joined the army at Prosek.

Statue in Berlin of General

Karl von Winterfeldt, Prussian commander killed at the Battle of Prague 6th May 1757 in the Seven Years War

Frederick took his commanders to the heights overlooking the Austrian positions to select a point for the attack. There they came under cannon fire. Frederick, Winterfeldt and Schwerin agreed on an immediate attack and that it should be launched beyond the Austrian right and be led by Schwerin and then Winterfeldt.

The Prussian army set off on a wide sweeping march around the Austrian right flank.

Seeing the Prussian Army moving across their front Prince Charles and Field Marshal Browne hurried troops to their open eastern flank. 40 companies of grenadiers and some 15 regiments of cavalry concentrated in the area of Sterbohol. They were in time to meet the oncoming attack by Lieutenant General Schönaich and a large force of Prussian cavalry giving rise to a drawn out and indecisive struggle between the mounted forces.

Schwerin had led the Prussian vanguard in a curving route to the east of the Austrian positions that had taken the columns through the village of Poczernitz. There the Prussian artillery had stuck fast in the narrow streets. The infantry was forced to bypass the village.

An added obstacle were the numerous fish ponds. While the time of year meant the ponds were drained of water, they were filled with deep mud in which many infantrymen became enmired.

The Prussian infantry columns wheeled to their right and launched an attack against the Austrian lines between Hostavitz and Sterbohol. The infantry attempted to press the attack without firing in accordance with the newly devised doctrine. They faced a heavy fire from Austrian guns positioned on the Homole Berg and the Austrian grenadiers and suffered high casualties. Several Prussian regiments crumbled in disorder in the face of the Austrian fire.

At this point Winterfeldt was riding in front of the regiment of Schwerin when he was wounded by a musket ball in the neck and fell to the ground. Schwerin himself came up at this point and oversaw the removal of the grievously wounded Winterfeldt from the field. Schwerin then took up the colour of his own regiment and began to lead it forward in a renewed attack when he was struck by a blast of canister which killed him outright.

Death of Field Marshal Schwerin at the Battle of Prague 6th May 1757 in the Seven Years War: picture by Johann Christoph Frisch

By around 11am the Austrians were pushing the Prussian infantry back.

At this point the Prussians developed an infantry attack around the village of Kej where a gap existed between the regiments Prince Charles and Browne had committed to the eastern position and the Austrian troops holding the original north facing line. The Duke of Bevern was the senior commander in the area but the Prussian regimental commanders appeared to act on their own initiative: the regiments being Hautcharmoy, Tresckow, Meyerlinck, Darmstadt, Prinz von Preussen, Kannacher and Wied (28, 32, 26, 12, 18, 30 and 28).

Finding the flank of the Austrian regiments the Prussians turned south and began to assault the Austrian line.

At the extreme south of the Austrian position Lieutenant General von Zieten decisively acted in the cavalry struggle by attacking the Austrian cavalry on its right flank with the Puttkamer and Werner Hussar Regiments.

Caught between the infantry assault on its left and Zieten’s hussars on its right the Austrian force between Sterbohol and Hostawitz collapsed, the majority heading for Prague, but some retreating to the South.

General Kheul rallied much of the retreating Austrian infantry on the western side of the valley that runs between Maleschitz and Hrdlorzez. A further sharp fight took place as the Prussians attempted to storm the Austrian positions in which the regiment of Winterfeldt suffered heavy casualties. The Austrians were forced to withdraw from this position into Prague as General Zieten took his cavalry through Neu Straschnitz beyond their right flank.

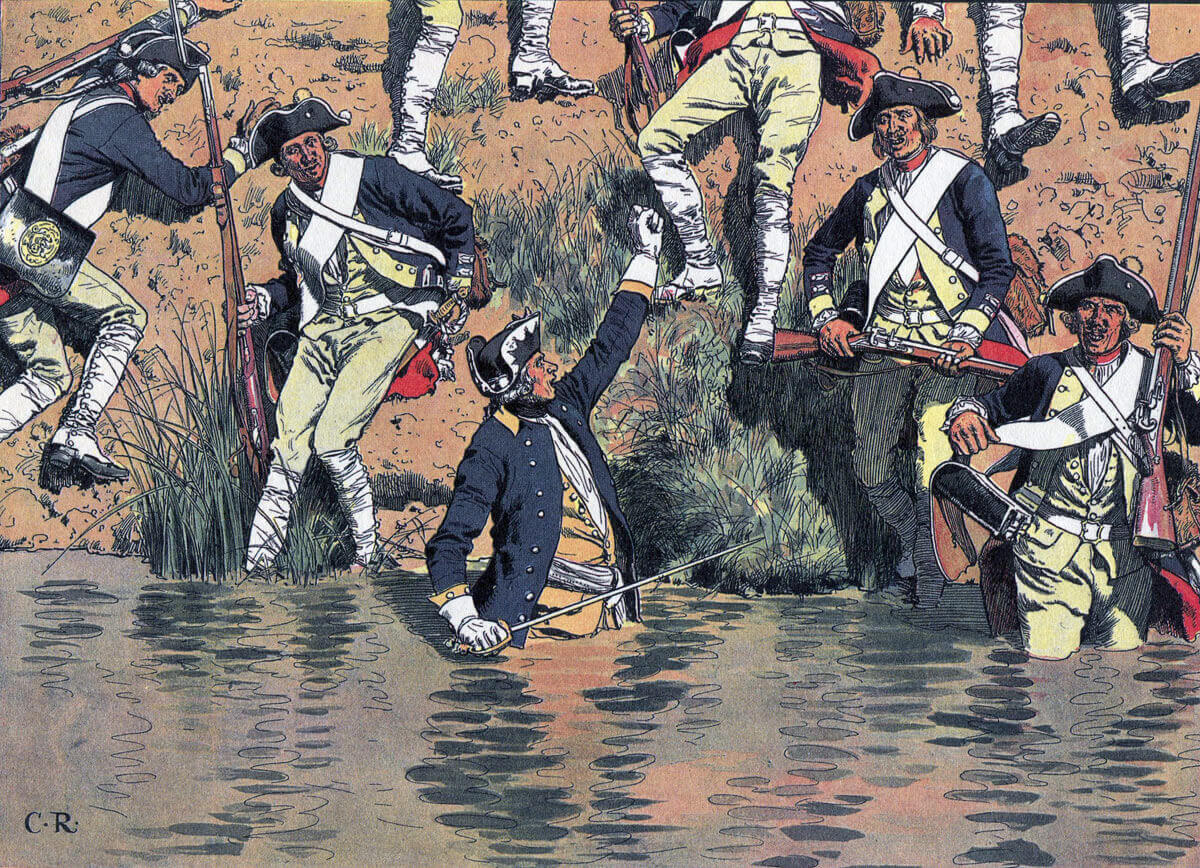

On their left flank Prince Henry crossed the Roketnitzer-Bach River with the Itzenplitz Regiment before launching his attack. The withdrawal of the Austrian infantry was covered by repeated counter-attacks by the Austrian cavalry. By the end of the afternoon the Austrian army had retreated into Prague, other than those regiments that had escaped to the South.

During the battle Frederick had sent orders to Field Marshal Keith to send a force to cross the Moldau upstream of Prague and cut off the Austrian retreat to the South. The bridging teams became stuck in the difficult roads and the force was unable to cross the river in time.

The Battle of Prague: Casualties: 14,300 Prussian casualties: 13,400 Austrian casualties, including the loss of 4,500 prisoners and 60 guns taken.

Aftermath to the Battle of Prague: Following the Battle of Prague Frederick began a siege and bombardment of Prague. In early June 1757 the Prussian king received news that Field Marshal Daun was advancing with a large Austrian army from Eastern Bohemia to relieve the city. Frederick sent the Duke of Bevern with a small army to block Daun’s advance. On 13th June 1757 Frederick set off to join Bevern and on 15th June the Prussian army assembled at Malotitz before fighting the fateful Battle of Kolin.

The Battle of Prague: Anecdotes:

- The Battle of Prague was hailed as a great Prussian victory. It is said that it should have been a greater one. The Prussian King Frederick II was suffering from a ‘stomach bug’ on the day. This seems to have caused him to leave the initial decision making to Schwerin. Schwerin led the march around the Austrian flank and resolved to commit the Prussian attack around Sterbohol. Frederick’s later comment was that Schwerin should have marched a further 2 kilometres before turning the Prussian columns to launch their assault. This would have taken the Prussian columns around the Austrian rear. The difficulty the Prussians faced was their limited knowledge of the terrain. The dilemma that arose in this battle as in other battles of the war was in balancing sufficient reconnaissance with speed of action. Frederick’s genius was ruthless action. This came at great cost in lives as he frequently acted before he had sufficient information on the lay of the land.

- A major contribution to the Prussian victory was the infiltration of the Prussian infantry battalions through the gap around Kej. There seems to have been little high ranking direction for this movement, with the initiative coming from individual regimental and battalion commanders, such as Colonel Herzberg. Major General Manstein commanded a force of four grenadier battalions in the turning movement.

- The river crossing made by the Itzenplitz regiment is a celebrated moment in Prussian military history. Prince Henry plunged into the river to encourage the soldiers to cross the Roketnitzer-Bach and nearly disappeared in the deep water.

- The casualties on both sides were appalling. The Prussians lost Field Marshal Schwerin and General Winterfeldt, both officers of considerable importance to King Frederick. Other significant officers killed were Lieutenant General Hautcharmoy and Major Generals Schöning and Blanckensee. The battle began the process of depriving Frederick of his closest confidants which continued throughout the war, finally leaving him almost friendless. Thousands of veteran Prussian infantrymen died in the attacks on the Austrian grenadiers and artillery around Sterbohol.

- On the Austrian side the casualties were nearly as great. The most grievous loss for Austria was the fatal wounding of Field Marshal Browne. Acting as Austrian deputy commander, Field Marshal Browne was struck down by a cannon shot in the fighting around Sterbohol. The Austrian regiments were left without senior direction at a critical point in the battle.

- If the Prussian victory is attributable to any senior officer, that officer is Lieutenant General Zieten, for his decisive intervention on the Prussian left flank. The flank attack by Zieten’s hussars swung the confused cavalry battle south of Sterbohol in the Prussian favour. Zieten’s subsequent advance was decisive in turning the Austrians out of their fall-back position at Maleschitz.

- Following the Battle of Prague, Frederick abandoned his practice of requiring the Prussian infantry to advance without firing. The battle taught him the importance of infantry fire power.

References for the Battle of Prague:

Frederick the Great by Thomas Carlyle

Frederick the Great by Christopher Duffy

The Army of Frederick the Great by Christopher Duffy

The Army of Maria Theresa by Christopher Duffy

In particular see the detailed and graphic account of the battle in ‘The Wild Goose and the Eagle A Life of Marshal von Browne 1705-1757’ by Christopher Duffy.

The previous battle in the Seven Years War is the Battle of Lobositz

The next battle in the Seven Years War is the Battle of Kolin