Frederick the Great’s disastrous defeat by the Austrians caused by Frederick’s overconfidence

The previous battle in the Seven Years War is the Battle of Prague

The next battle in the Seven Years War is the Battle of Rossbach

Battle: Kolin

Date of the Battle of Kolin: 18th June 1757

Place of the Battle of Kolin: In Central Bohemia

War: The Seven Years War

Contestants at the Battle of Kolin: Prussians against an Imperial Austrian Army comprising the various nationalities that made up the Austro-Hungarian Empire (Austrians, Hungarians, Bohemians, Netherlanders, Silesians, Croats, Italians and Moravians).

Generals at the Battle of Kolin: King Frederick II of Prussia commanding the Prussian Army against Field Marshal Daun commanding the Austrian Army.

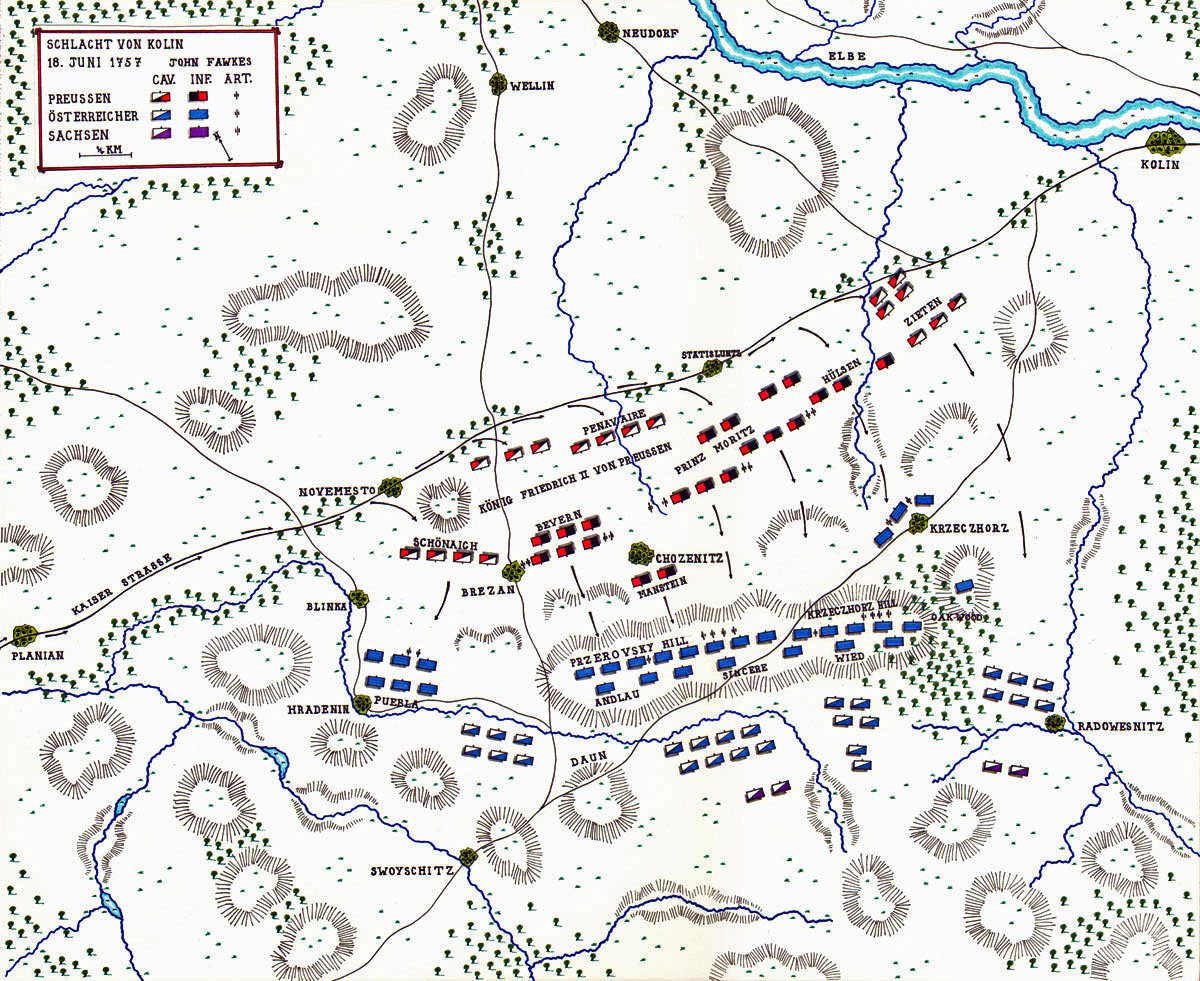

Size of the Armies at the Battle of Kolin: 32,000 Prussians (18,000 infantry, 14,000 cavalry) and 88 guns against 44,000 Austrians (28,960 infantry, 14,000 cavalry) and 145 guns.

Winner of the Battle of Kolin: The Austrians, emphatically.

Frederick the Great after the Battle of Kolin 18th June 1757in the Seven Year War: picture by Julius Schrader

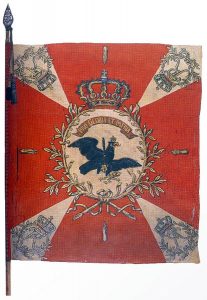

The Colour of Prussian Infantry

Regiment Number 17 Manteuffel

seized at the Battle of Kolin 18th June 1757 and held in the Austrian Army Museum in Vienna.

Uniforms and equipment at the Battle of Kolin:

The Prussian infantry and artillery wore a dark blue coat turned back at the lapels, cuffs and skirts, with britches and black thigh length gaiters. Each soldier carried on a cross belt an ammunition pouch, bayonet and ‘hanger’ or small sword. Headgear for the line companies was the tricorne hat, with a flattened front corner, bound with white lace. Grenadiers wore the distinctive mitre cap with a brass plate at the front. Fusilier infantry regiments and artillery wore a smaller version of the grenadier cap.

The infantry carried a musket as the main weapon. This single shot firearm could be loaded and fired by a well trained soldier around 3 to 4 times a minute. As an early improvement Frederick introduced the iron ramrod and then the reversible ramrod (the soldier did not have to worry whether he had the ramrod the right way round) which increased the rate of fire of his infantry, the old wooden ramrod being liable to break in the stress of battle.

The Prussian infantry regiment was based on the cantonment with soldiers joining their local regiment. In peacetime soldiers were released for key agricultural times, sowing and harvesting. In the autumn, reviews were conducted of all regiments to check they were up to the required standard. Each year regiments were selected to undergo review at Potsdam under the eye of the King. Officers whose soldiers’ performance was considered by Frederick to be substandard were subject to a public tongue lashing and in extreme cases dismissal on the spot.

The efficiency of the Prussian regiments at drill enabled them to move about the battlefield with a speed and manoeuvrability that no other European Army could equal. The Battle of Rossbach is a striking example of this facility.

The Prussian Foot Guards at the Battle of Kolin 18th June 1757 in the Seven Year War: picture by Carl Röchling

Heavy cavalry of the period comprised cuirassiers and dragoons. The Prussian cuirassiers wore a white coat, steel cuirass, white britches and thigh boots. Prussian Dragoons wore a light blue coat. The headgear was a tricorne hat. Weapons were a heavy cavalry sword and single shot flintlock carbine.

Prussian Kürassier-Regiment von Seyldlitz No 8: picture by Adolph Menzel as part of his series of pictures ‘Die Armee

Friedrichs des Grossen in ihrer Uniformierung’

The light cavalry arm was provided by the Prussian Hussar regiments. The true hussars were Hungarians in the Austrian service. The hussars of other armies were given the same dress as the original hussars and required to perform a similar light cavalry role of reconnaissance and harassing the enemy’s outposts and supply columns.

Following the Battle of Mollwitz and in particular after the First Silesian War the Prussian Hussars were re-organised and re-trained to provide an efficient scouting and light cavalry service. Frederick found in Colonel von Zieten the ideal officer to implement the improvements in the hussar regiments. The Prussian Hussars wore the traditional hussar dress of tunic, britches, dolman (slung jacket), busby (fur hat) with bag, sabretache (leather wallet on straps hanging from the belt) and curved sword.

Unlike the original Hungarian Hussars of the time who were considered to be little more than indisciplined freebooters the Prussian Hussars were well able to take a position in the cavalry line and perform valuable service in battle, as at the Battle of Hohenfriedburg and on other occasions.

The Austrian infantry wore white coats with lapels, cuffs and skirts turned back showing the regimental lining colour. Headgear was the tricorne hat for line infantry and bearskin cap for grenadiers. The infantry weapons were musket, bayonet and hanger small sword. Heavy cavalry wore white coats and hats as for the infantry and were armed with a heavy sword and carbine. Some dragoons wore a bearskin cap. The Austrian army contained a large number of irregular units notably the Pandours from the Balkans who wore their ethnic dress without uniformity. Hungarian Hussars provided the light cavalry arm. These Hussars, dressed as described for the Prussian Hussars, were considered to be little more than bandits but were highly effective in all the roles required of light cavalry.

Following the humiliations of the First and Second Silesian Wars at the hands of Frederick the Great and his Prussian army the Austro-Hungarian authorities implemented wide ranging reforms of every branch of their army. Prince Joseph Wenzel von Liechtenstein after his experience of the devastating effectiveness of the massed Prussian artillery at the Battle of Chotusitz undertook a root and branch reform of the Austrian artillery, using his own fortune to fund the changes. The Austrian artillery that entered the Seven Years War was considered more effective than its Prussian counterpart.

Frederick implemented significant improvements to the Prussian Army between the two Silesian wars. The eleven years of peace before the Seven Years War enabled Frederick to bring the various arms of the Prussian service to a further high pitch of efficiency. Each year the regiments were subjected to a training cycle that culminated in reviews at Potsdam under the King’s exacting eye. Autumn manoeuvres were held in Silesia, the area where much of the expected warfare would be conducted (see the benefit of these manoeuvres at the Battle of Leuthen).

The Prussian infantry was a tested and established asset and required little improvement. Most of the innovation was targeted at the cavalry, artillery and technical arms.

One unfortunate development from the Silesian Wars was that Frederick formed the view that his infantry could win their battles simply by the steadiness of their advance. The Seven Years War began with the Prussian infantry doctrine being to advance with muskets at the shoulder and not to pause to fire on the enemy. The Battle of Prague showed this doctrine to be badly misguided and it was abandoned after causing the Prussians substantial casualties.

The Prussian infantry was soon trained to advance making brief halts to fire and reload, enabling it to deliver successive volleys as it marched up to the opposing army, a technique used to devastating effect at the Battle of Rossbach.

During the course of the Seven Years War Frederick extensively re-organised the artillery. New equipment was introduced, the guns standardised and the artillery formations overhauled. Frederick introduced horse artillery that could move around the battlefield.

Frederick brought the Prussian cavalry to a level of effectiveness unrivalled by any other European Army of any period. The basic requirement was a high standard of horsemanship in every soldier. A trooper was required to ride his horse every day, an exacting obligation in peacetime. Contrast this with the practice of the British regiments of horse and dragoons of the time, in which as a measure of economy the horses had their shoes struck off and were put out to grass unridden for the whole of the summer (see Viscount Molesworth’s standing orders for his dragoon regiment).

Every year Frederick exercised the cavalry during the autumn manoeuvres. Frederick required the cuirassier and dragoon regiments to form line at the gallop and deliver a charge, with the troopers so close that they rode knee behind knee with the horses touching. Frederick developed the capability of the cavalry year by year. Finally he required his mounted regiments to be able to deliver three such charges one after the other at full gallop.

The effect of this exacting training was graphically illustrated by the performance of the Prussian cavalry force led by General von Seydlitz against the Russians at the Battle of Zorndorf on 25th August 1758. Seydlitz’s squadrons crossed the Zabern-Grun stream, climbed the steep far bank and moved through an area of scrub, before forming two lines of hundreds of troopers at the gallop, so close together that the horses were touching, and delivering a devastating charge at full gallop against unshaken Russian infantry, who were overwhelmed. Against cavalry of this quality it mattered little whether the infantry was in line or square.

This extraordinary ability contrasted with most other European cavalry regiments which would form for the charge at the halt and then attack in a loose formation which would be lost in the course of the charge, ending with the horses blown and all cohesion gone. If the infantry under attack seemed unduly aggressive, the attacking cavalry would be liable to swerve around them or pull up.

It was Frederick’s order that any Prussian cavalry commander receiving a charge at the halt would be tried by court-martial. Commanders had the discretion to attack if they considered that a favourable opportunity existed, without waiting for orders.

The Battle of Rossbach is another good example of the quality of the Prussian heavy cavalry and its ability to deliver battle winning charges through remaining under the tight control of its commander.

Account of the Battle of Kolin:

Following the Prussian success in defeating the main Austrian army commanded by Prince Charles of Lorraine and Field Marshal Browne at the Battle of Prague on 6th May 1757 and the subsequent Prussian siege of the city, Field Marshal Daun began his advance with a substantial Austrian army from Eastern Bohemia to relieve Prague.

Hearing of Daun’s advance Frederick directed the Duke of Bevern with his force of 24,600 troops to keep Daun in check. This he seemed to be doing.

On 13th June 1757 Frederick set out with a small force to join Bevern. Frederick spent the night at an inn called ‘Zum Letzten Pfennig’ where he received the unexpected and unwelcome news that Daun was advancing.

Frederick moved east towards the Elbe side town of Kolin, until he encountered cavalry from Daun’s army. Frederick withdrew to the town of Malotitz where he waited to concentrate his forces: Bevern’s troops and further regiments summoned from the Prussian army outside Prague.

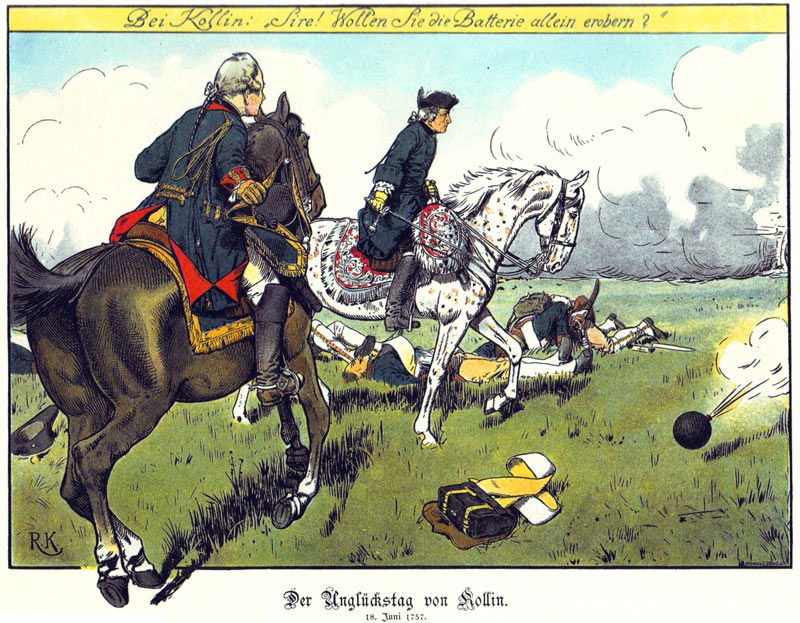

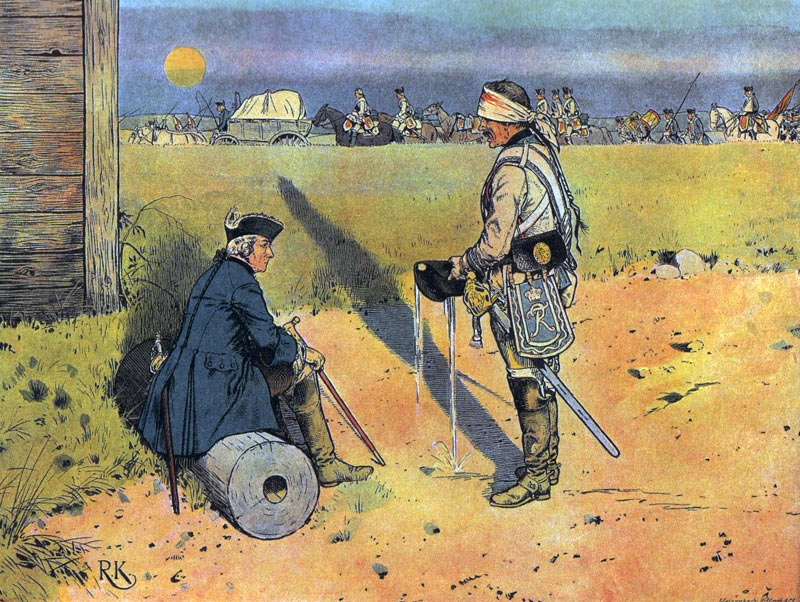

King Frederick II of Prussia at the Battle of Kolin 18th June 1757 in the Seven Year War by Richard Knotel

On 15th June 1757 Frederick’s scout, Captain Gaudi, observing from a church steeple, spotted the Austrian camp some 3 miles distant from the Prussians.

Prussian Infantry Regiment Fürst

Moritz No 22 (the regiment lost 26

officers and 1,165 men in the battle):

picture by Adolph Menzel as part of

his series of pictures ‘Die Armee Friedrichs des Grossen in ihrer Uniformierung’

Frederick had some difficulty in accepting Gaudi’s report that he was in the presence of the whole of Daun’s army and took no action during 16th June 1757.

Frederick resolved to continue the march east along the Kaiser Strasse until clear of the Krzeczhorz Hill and then to wheel around the Austrian right flank before launching his attack. The Prussian advance was headed by the valorous and reliable Major General Hϋlsen with a force of infantry and the Stechow Dragoons D11. He was to leave the Kaiser Strasse and wheel in to attack the ridge once past the village of Krzeczhorz.

Lieutenant General Zieten was to follow Hϋlsen and take position to protect his left flank with 50 squadrons of hussars. A substantial force of cuirassiers and dragoons followed Hϋlsen and Zieten.

The army’s remaining infantry would be held in reserve while Hϋlsen’s attack went in with a small force of cavalry at the rear of the column on the Kaiser Strasse.

Frederick briefed his generals and their adjutants from the window of the Golden Sun.

Prussian Königs Leibgarde (the regiment lost 24 officers and 475 men in the battle): picture by Adolph Menzel as part of his series of pictures ‘Die Armee Friedrichs des Grossen in ihrer Uniformierung’

Soon after midday Bevern considered that the Prussians had insufficient numbers to attack the Austrians and urged the king to avoid battle. Prince Moritz who arrived with the force from Prague urged Frederick to attack saying “Your Majesty’s presence is worth 50,000 men”.

On 17th June 1757 the Prussian army began a side step to the North towards the Kaiser Strasse, the main route crossing Bohemia from west to east. To his chagrin Frederick found that Daun had conformed to his move and the Austrians were taking up positions on the chain of low hills that followed the route of the Kaiser Strasse along its south side.

On 18th June 1757 the Prussian army reached the Kaiser Strasse at Planian and turned east along the highway. It promised to be a day of stifling heat.

Frederick took what he expected to be a high point of vantage in the church spire at Planian and surveyed the hills through his telescope. He could see little. The army continued on its march until a halt was called while the king attempted a further review of the area from the upper floor of an inn called the Golden Sun.

The Prussian Foot Guards at the Battle of Kolin 18th June 1757 in the Seven Year War: picture by Richard Knotel

The Austrian army could be seen disposed along the ridge along the South of the Kaiser Strasse from Przerovsky Hill to the Krzeczhorz Hill at the far end of the low ridge. Daun had placed his cavalry so as to take advantage of the terrain rather than following any battlefield convention. Bevern and Zieten urged that Frederick should not attack. With 8 successive victories against the Austrians Frederick could not be persuaded that a Prussian attack might fail however great the odds against them.

Prussian Husaren-Regiment von Zieten No 2: picture by Adolph Menzel as part of his series of pictures ‘Die Armee Friedrichs

des Grossen in ihrer Uniformierung’

Frederick resolved to continue the march east along the Kaiser Strasse until clear of the Krzeczhorz Hill and then to wheel around the Austrian right flank before launching his attack. The Prussian advance was headed by the valorous and reliable Major General Hϋlsen with a force of infantry and the Stechow Dragoons D11. He was to leave the Kaiser Strasse and wheel in to attack the ridge once past the village of Krzeczhorz.

Lieutenant General Zieten was to follow Hϋlsen and take position to protect his left flank with 50 squadrons of hussars. A substantial force of cuirassiers and dragoons followed Hϋlsen and Zieten.

The army’s remaining infantry would be held in reserve while Hϋlsen’s attack went in with a small force of cavalry at the rear of the column on the Kaiser Strasse.

Frederick briefed his generals and their adjutants from the window of the Golden Sun.

Soon after midday the king mounted outside the inn and drew his sword. An hour later the advance force of Hϋlsen and Zieten marched off down the Kaiser Strasse.

The striking feature of the ensuing battle was Frederick’s apparent change of plan from a flanking attack around the Austrian right flank beyond the village of Krzeczhorz to a frontal attack on the low hills directly from the Kaiser Strasse. This was in contradiction to the instructions he had given his generals in the Golden Sun Inn and, not surprisingly, gave rise to considerable confusion.

The trigger for this change of plan appears to have been artillery fire opened by the Austrians from the village of Krzeczhorz on Hϋlsen’s advancing infantry. Frederick seems to have realised that the wily Daun was moving his line east along the ridge to match the Prussian advance.

Hϋlsen’s troops stormed through Krzeczhorz to find themselves confronted, not by an open flank, but by Wied’s division of infantry.

Zieten’s hussars, advancing beyond Krzeczhorz, drove back Nadasti’s Hussars and Croats and halted to the east of the Oak Wood as Frederick had directed.

Prussian Infantry Regiment von Hülsen

No 21 (the regiment lost 30 officers and

966 men in the battle): picture by Adolph Menzel as part of his series of pictures ‘Die Armee Friedrichs des Grossen in ihrer Uniformierung’

In the meantime Frederick directed Prince Moritz, instead of continuing in the path of Hϋlsen’s troops along the Kaiser Strasse, to turn immediately off the highway and assault the line of hills. Moritz resisted this change of plan and a substantial row took place between him and his sovereign. Eventually he complied and the Prussian infantry began the assault on Krzeczhorz Hill.

The attack was in the teeth of a substantial deployment of Austrian artillery positioned on the ridge which opened fire and inflicted heavy casualties on the advancing Prussian infantry.

On the right of Prince Moritz’s force Major General Manstein’s Prussian infantry battalions moved off the Kaiser Strasse and drove the Croat skirmishers out of Chozenitz before moving on to assault the Austrian positions on Przerovsky Hill.

Under Frederick’s supervision Manstein attacked the hill 3 times between 3.30 and 4.30pm. While the determined attacks failed to dislodge the Austrians they ensured that General Andlau did not continue the move of his division to support of the Austrian formations under attack on the Krzeczhorz Hill.

Most of the Prussian army was by this time attacking along the ridge line.

On the right reinforcements of infantry enabled the Austrians to recover the area of the Oak Wood. The Austrian Lieutenant General Starhemberg pushed on to recover the village of Krzeczhorz.

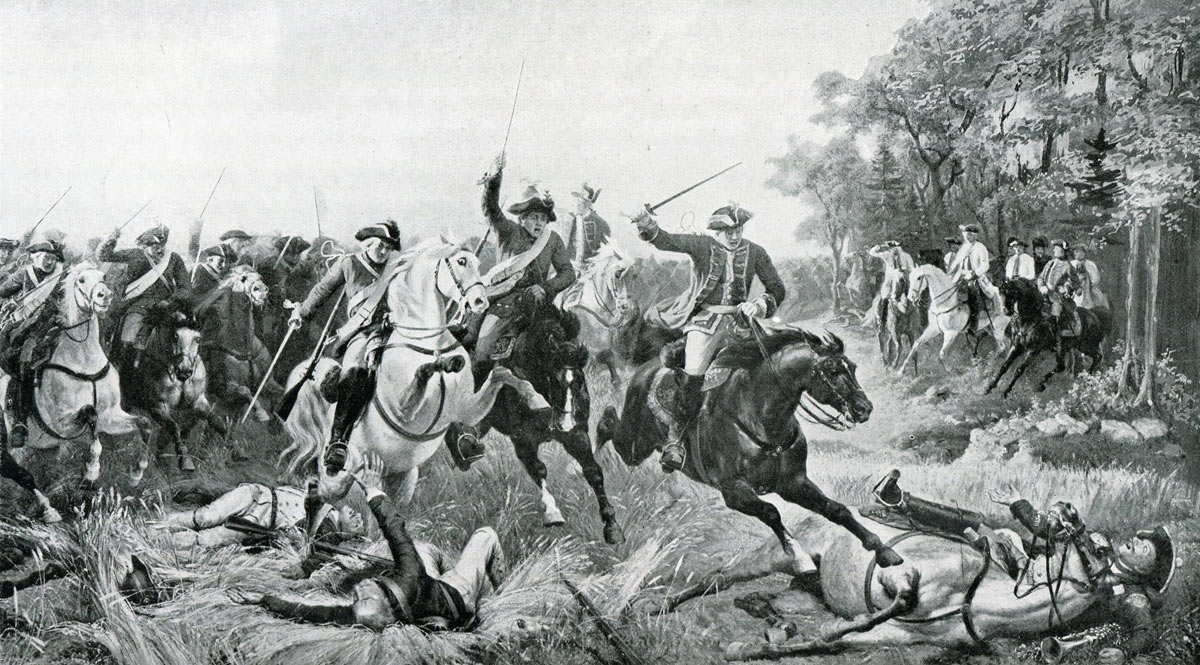

Attack of General von Krosigk’s Prussian cavalry brigade on the Austrian infantry of General Sincere’s division, taken up by Colonel von Seydlitz after Krosigk’s death: Battle of Kolin 18th June 1757 in the Seven Year War: a contemporary picture

It was at this point that Starhemberg’s division received a devastating cavalry charge on its right flank from Major General von Krosigk’s brigade of Prussian cuirassiers and dragoons. At the head of the Normann Dragoons (D1) von Krosigk was struck from his saddle by a blast of canister while urging his soldiers to attack to the last. The command of the brigade fell on Colonel Friedrich von Seydlitz who continued the charge with his own regiment, the Rochow Cuirassiers (C8), the Prinz von Preussen Cuirassiers and the Normann Dragoons, riding down the Austrian Wϋrttemburg Dragoons, the Saxon Carabiniers and the infantry regiments of Haller, Baden and Deutchmeister in their rampage through the division of Sincère. The charge ran out of steam as the brigade suffered extensive casualties and became dispersed.

Regiments of the Austrian army: Grenadiers of the Hungarian regiments Haller, Bethlen and an Austrian regiment: Battle of Kolin 18th June 1757 in the Seven Year War: Picture by David Morier

All along the ridge the Prussians attempted to sustain a footing and drive Daun’s army back, but there were too many Austrians and they fought too well.

Lieutenant General Penavaire took his force of Prussian cavalry forward in an attack that drove back the Austrian cavalry but was held by Starhemberg’s infantry.

The Duke of Bevern brought forward the last of the Prussian infantry to launch what was to be the final Prussian effort. The attack went in on the Prussian left. They came under heavy artillery fire and the First Battalion of the Prussian Garde was charged and severely mauled by the Darmstadt Dragoons (see the graphic illustration by Carl Röchling).

Bevern’s force pushed into the Austrian line and formed across the ridge. It was at this point that the Netherland Ligne Dragoon Regiment led a charge of Austrian cavalry on the rear of the Prussian line which collapsed. All along the ridge the exhausted Prussians fell back to the Kaiser Strasse.

Hϋlsen fought a vigorous rear guard action in the village of Krzeczhorz and Zieten’s hussars withdrew in good order from their position on the left. The conduct of these two officers helped deter the exhausted Austrians from a vigorous follow-up to their victory.

Frederick left the battlefield and rode to Nimburg in despair at his defeat. Prince Moritz was left to bring the remains of the army out of action. The King moved on to his old headquarters outside Prague where he deputed his brother Prince Henry to withdraw the Prussian army from Bohemia.

Casualties at the Battle of Kolin: 13,768 Prussian casualties and 45 guns lost against 9,000 Austrian casualties.

Aftermath to the Battle of Kolin: On 20th June 1757 Frederick abandoned the siege of Prague and withdrew his army into Northern Bohemia. Frederick took part of the army to Leitmeritz on the eastern side of the Elbe while his brother Prince August William commanded the force on the western bank.

With unexpected speed the Austrians moved against Prince August William and bundled his army out of Bohemia into Saxony.

In the summer of 1757 Frederick manoeuvred against the Austrians who outnumbered his force by 100,000 men to 50,000. Prince Henry persuaded Frederick against an attack on the Austrians to the great relief of the Prussian army.

Frederick was aware that his terrible defeat at Kolin encouraged his various foes to move against him. The Swedes stood poised to invade Pomerania while the Russians menaced from the far side of the Oder. An army of Hanoverians and Protestant Germans, allies of the Prussians, suffered defeat at the hands of the French at Hastenbeck on 26th July 1757 and another French army under Prince Soubise moved towards Prussian territory from the Rhine accompanied by the Reichsarmée commanded by the Austrian Field Marshal Prince Joseph Friedrich von Sachsen-Hildburghausen.

Acting with decision Frederick left the Duke of Bevern with 40,000 troops in Silesia to cover Daun’s Austrian army and marched at speed to meet Soubise and Hildburghausen (see the Battle of Rossbach).

Frederick the Great being offered water by one of his cuirassiers after the Battle of Kollin 18th June 1757 in the Seven Year War: picture by Richard Knötel

Anecdotes from the Battle of Kolin:

- It was in the frenzied fighting at the Battle of Kolin that Frederick the Great is said to have bawled at Manstein’s flinching Prussian infantry “Dogs! Do you want to live forever?”

- Frederick the Great had not encountered defeat before the Battle of Kolin. He suffered a period of near despair during his stay at Leitmeritz in the summer of 1757, exacerbated by news of the death of his mother Queen Sophia Dorothea on 28th June 1757.

- One of the most striking features of Frederick the Great was his extraordinary ability to recover from disaster and reconstitute the resilient Prussian army. This is what he proceeded to do. It is hard to comprehend that Frederick inflicted the crushing defeat of Rossbach on the French and the Reichsarmée on 5th November 1757 within 5 months of the disaster of Kolin.

References for the Battle of Kolin:

Frederick the Great by Thomas Carlyle

Frederick the Great by Christopher Duffy

The Army of Frederick the Great by Christopher Duffy

The Army of Maria Theresa by Christopher Duffy

The previous battle in the Seven Years War is the Battle of Prague

The next battle in the Seven Years War is the Battle of Rossbach