The Allies prepare for the assault on the Gallipoli Peninsula by British, French, Australian and New Zealand troops at the end of April 1915

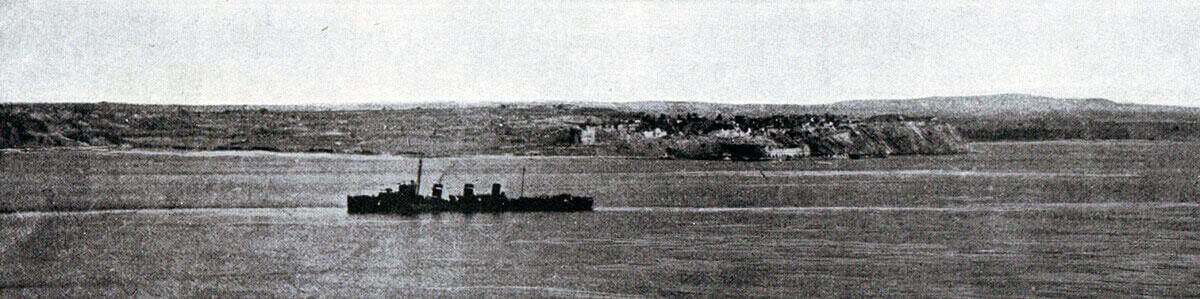

British destroyer passing Sedd el Bahr at Cape Helles: Gallipoli Part II, March 1915 to January 1916 in the First World War

The previous battle of the First World War is Gallipoli Part I: Naval Attack on the Dardanelles

The next battle of the First World War is Gallipoli Part III: ANZAC landing on 25th April 1915

The Dardanelles and Gallipoli: The campaign during 1915 conducted by the British and the French, using British, French and Australian warships and British, French, Australian, New Zealand and Indian troops, to take the Gallipoli Peninsula, penetrate the Dardanelles waterway and capture Constantinople, thereby knocking the Ottoman Turkish Empire out of the First World War.

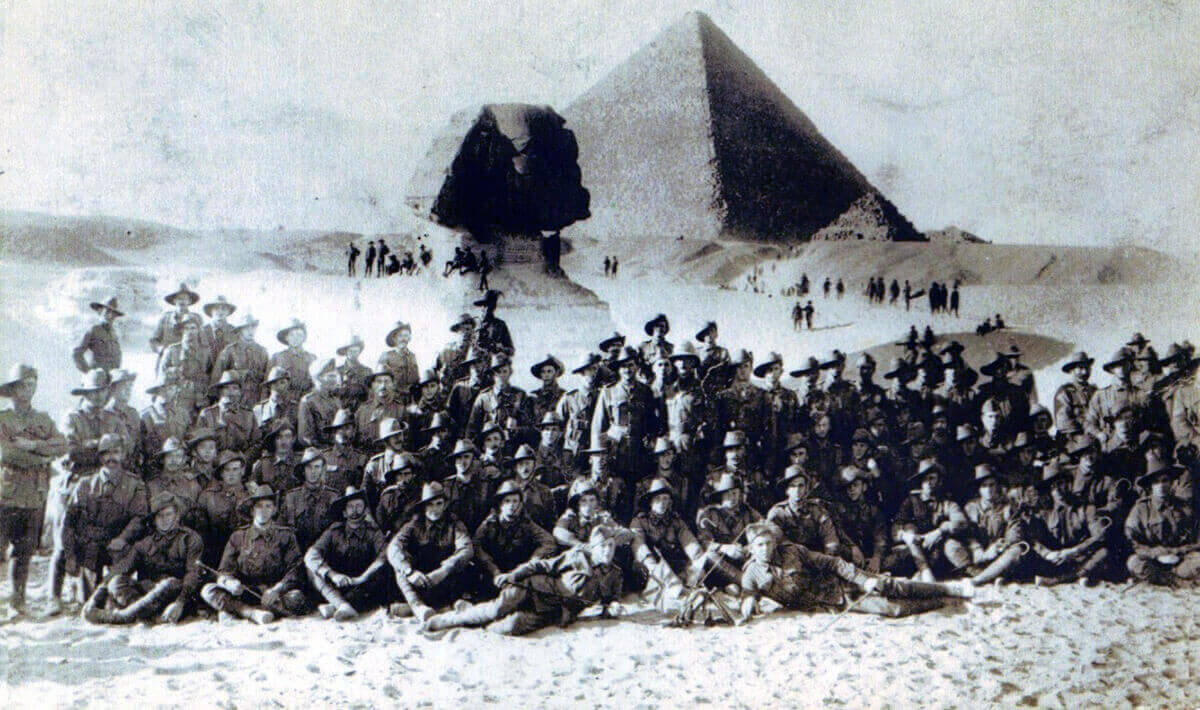

First Australian Division at Mena Camp in Egypt 1914 before leaving for the Gallipoli Peninsula: Gallipoli Part II, March 1915 to January 1916 in the First World War

Date: March 1915 to January 1916

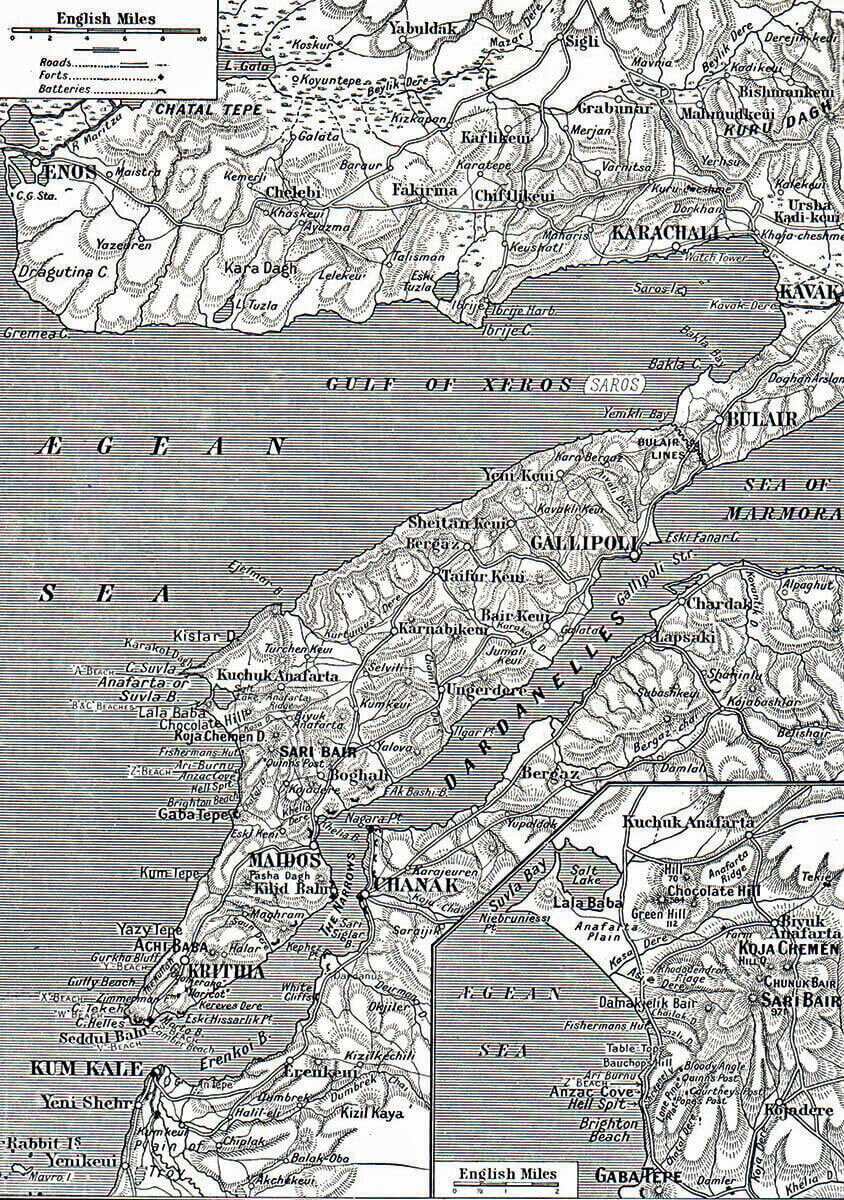

Place: The Gallipoli Peninsula forms the northern shore of the Dardanelles, the narrow waterway leading from the north east corner of the Aegean Sea to the Sea of Marmora, the city of Constantinople (in 1915 the capital of the Ottoman Turkish Empire) and then to the Black Sea.

War: The First World War also known as ‘The Great War’.

Contestants: British, Australian and New Zealand troops with French troops supported by British and French naval ships against Turkish troops and ships led by German senior officers.

Generals: General Sir Ian Hamilton led the Entente (British, French, Australian, New Zealand and Indian) troops until he was replaced by General Sir Charles Munro in December 1915. General Eric Liman von Sanders, a German officer, commanded the Turkish troops. Vice-Admiral Carden commanded the British and French fleets until mid-April 1915, when he was replaced by his deputy commander Vice-Admiral de Robeck. Admiral Guépratte commanded the French warships.

Winner: The final outcome was that the Entente Allies, Britain and France, withdrew from the Gallipoli Peninsula in December 1915 and January 1916 leaving the Turks victorious.

Part II: Genesis of the land attack on the Gallipoli Peninsula

The British and French naval attack on the Dardanelles waterway ended on 18th March 1915 with the sinking of three battleships and the damaging of a battlecruiser.

It was the view of the admirals that the naval attack could not succeed unless land forces captured the Gallipoli peninsula and destroyed the mobile land batteries that were causing so much damage to the naval ships.

The decision by the British and French governments to land troops on the Gallipoli Peninsula was confused and drawn out and was only finally made once the naval attack appeared to have failed.

Royal Navy midshipmen picnicking on the Greek island of Lemnos: Drewery, winner of the VC at V Beach is on the left

It is asserted that if the British and French military landings had taken place without the naval attack the Turks would have been taken by surprise and the Gallipoli Peninsula could have been overrun with little difficulty.

However the decision to launch the land attack on Gallipoli was triggered by the prospect of significant loss of prestige from the failure of the naval attack, with the feared result of pushing Bulgaria and possibly Rumania into the German camp (in the event Bulgaria did join the Central Powers while Rumania in 1916 joined Russia, France and Britain). Without the spur of the failure of the naval attack it seems unlikely that the British and French governments would have committed themselves to the land attack.

On 10th March 1915 Lord Kitchener informed the British War Cabinet that he was sending the 29th Division to the Mediterranean for possible operations on the Gallipoli Peninsula and that troops in Egypt would join the expedition, the 1st Australian Division and the joint Australian-New Zealand Division, together forming the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps (ANZAC) commanded by Lieutenant General Birdwood. The Admiralty sent the Royal Naval Division to Mudros, the British and French base on the Greek island of Lemnos.

Australian troop transport SS Geelong leaving Hobart in Tasmania on 20th October 1914 with 12th Battalion, 9th Battery 3rd RFA Brigade and C Squadron 3rd Light Horse, Australian Imperial Force: Gallipoli Part II, March 1915 to January 1916 in the First World War

The French supplied a division formed from reservists in France and soldiers from their North African colonies.

Kitchener’s estimate was that there would be some 130,000 allied (British, ANZAC, French and Russian) troops available for operations against Constantinople from Gallipoli and from the Caucasus, against 180,000 Turkish troops. In fact the allied numbers were around 115,000 of which 40,000 were Russians in the Caucasus to the east of Turkey.

French troops on a transport on their way to the Gallipoli campaign: Gallipoli Part II, March 1915 to January 1916 in the First World War

On 11th March 1915 General Sir Ian Hamilton was appointed to command the ‘Mediterranean Expeditionary Force’ with Major General Braithwaite as his chief of staff. These officers were in London and left the next day for the Mediterranean by train to Marseille and warship to Mudros on Lemnos.

Kitchener’s instructions to Hamilton were that Kitchener did not believe it would be necessary for the army to attack Gallipoli as the naval assault was likely to be successful, but if it did become necessary Hamilton was to act without delay. The military authorities in London were unable to give Hamilton much information, not even a reliable map of Gallipoli. It was estimated correctly that there were around 40,000 Turkish troops in the Gallipoli Peninsula.

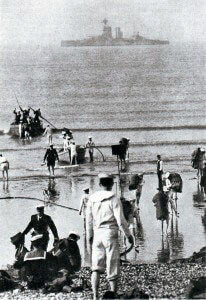

Royal Navy landing party at Mudros on the Greek island of Lemnos with a battleship in the background

There appears to have been a Greek plan to invade Gallipoli dating from 1912. This plan involved the landing of 150,000 Greek troops, double the number in the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force. Hamilton said he was unable to find a copy of the plan in London.

General Hamilton and General d’Amade, the French army commander, both arrived at Mudros on the Island of Lemnos, the British and French base, on 17th March 1915, the day before the final naval attack. At this stage the sailors were still confident of forcing their way through the Dardanelles.

HMS Inflexible, British battlecruiser badly damaged by Turkish shore based artillery fire on 18th March 1915

Admiral de Robeck informed the two generals that his primary difficulty was the guns of the Turkish land based artillery units, which were mobile and difficult to locate. He requested that the army land on Gallipoli and deal with these guns.

Following the naval attack on 18th March 1915 with its substantial loss in ships Hamilton telegraphed London to say that he did not believe the Fleet could penetrate the Dardanelles unless the army took the Gallipoli Peninsula. On 22nd March 1915 Admiral de Robeck reported to London in the same terms.

The burden now passed to the army to take up the attack on the Turks. Due to the state of the land forces available landings could not take place before the middle of April 1915, by which time the Turks could be expected to have reinforced their Gallipoli garrison and built defences at the main landing points.

The Allied Military Force:

General Hamilton’s force laboured under several handicaps. While the 29th Division was composed of regular infantry battalions with one Territorial Force battalion, the other divisions, other than the handful of Royal Marine battalions in the Royal Naval Division, comprised recently raised war service units that were not fully trained and lacked much of the equipment needed. None of the units making up the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force had experience in the current war.

New Zealand troops digging trenches in Egypt before leaving for the Gallipoli landings: Gallipoli Part II, March 1915 to January 1916 in the First World War

The fighting on the Western Front in France showed that full artillery support was essential for assaults on entrenched lines. While shrapnel was effective against troops in the open high explosive was required to destroy trenches and fortified posts. Throughout the Gallipoli campaign the British troops were short of all ammunition but particularly of high explosive.

There was a general shortage of guns for the British, Australian and New Zealand troops on Gallipoli, particularly of heavier guns.

The naval ships, often the only source of heavy artillery support for army operations on Gallipoli, were equipped largely with armour piercing shells, ineffective against field fortifications or troops in the open.

Experience in France showed that troops engaged in trench warfare needed a wider range of weapons than the rifle, bayonet and machine gun issued pre-war. Trench mortars were highly effective at the tactical level as was a good supply of hand grenades (called bombs in the Great War). A very small number of trench mortars was provided to the troops in Gallipoli and there was at no time a supply of bombs. The troops were left to make their own bombs from empty Tickler’s jam tins, known as ‘Tickler’s Artillery’. The tins were given an explosive filler and packed with pieces of metal. A fuse lit by match or cigarette provided the detonation.

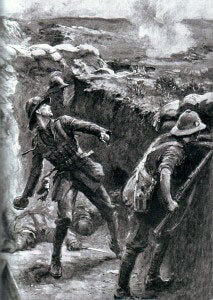

Lieutenant Forshaw 1st/9th Manchesters, Territorial Force winning the VC at Suvla Bay throwing Tickler’s jam tin grenades at attacking Turks for much of two days

Availability of small arms ammunition for rifles and machine guns often fell below critical levels on Gallipoli due to inadequacy of supply. Throughout 1915 all the belligerents were finding that pre-war estimates of ammunition consumption were hopelessly wrong and all countries spent the year desperately building up ammunition production. The priority for Britain was the supply of ammunition to the British Expeditionary Force in France, still considered woefully inadequate, leaving very little for the Gallipoli force.

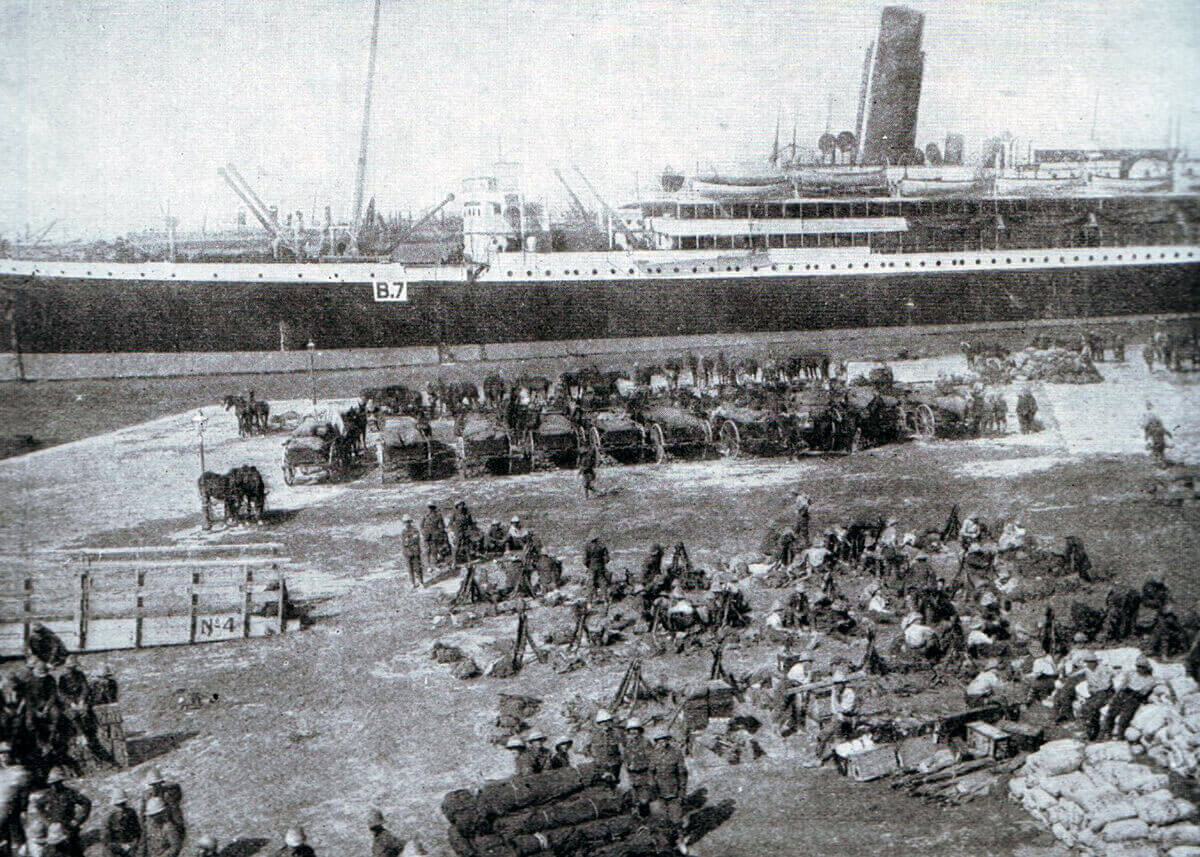

The two divisions from England, the 29th and the Royal Naval, were loaded onto transport ships in Britain in the expectation that they would disembark in a friendly harbour. It was not expected that the two divisions would go straight into a landing on a hostile shore. Before an opposed landing could be carried out on Gallipoli the ships had to be unloaded and re-loaded ‘tactically’; that is ensuring that units were together and had immediate access to their weapons, equipment and ammunition supplies.

Mudros in Lemnos contained minimal harbour facilities so the ships were sent on to Alexandria in Egypt to be re-loaded.

It took several weeks to sort out the chaos. In an extreme case it was found that one infantry battalion had men on four ships. Artillery guns had been separated from their ammunition and horses and waggons loaded in different ships.

On 8th January 1915 Lord Kitchener had informed the War Cabinet in London that the size of military force required to take the Gallipoli Peninsula was 150,000 men. He may well have taken this figure from the Greek plan of 1912. The troops now under General Sir Ian Hamilton’s command comprised 75,000 British, Australian, New Zealanders and French.

General Hamilton prepared to make his landing on the Gallipoli Peninsula with half the force considered necessary by Kitchener in January, comprising inexperienced and in the case of ANZAC and the Royal Naval Division substantially untrained and badly equipped troops, with insufficient guns, an inadequate ammunition supply, very few of the weapons required to attack a trench system, an inexperienced staff, an inadequate communications system for senior commanders to communicate with units ashore, no reliable maps, a complete lack of knowledge of the area to be attacked, an almost non-existent air force and no landing craft other than the navy’s wooden lighters.

The Turkish Garrison:

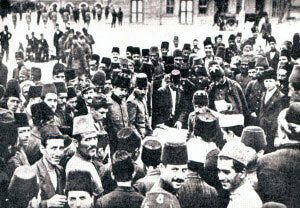

Turkish recruits reporting for service after the Ottoman Empire declared war on Britain and France: Gallipoli Part II, March 1915 to January 1916 in the First World War

The British and French naval attack on the Dardanelles put the Ottomans on notice that the area was vulnerable and that Constantinople itself was threatened. From then on the Turkish army built up its presence on both sides of the waterway.

By the 18th March 1915 the number of Turkish infantry on the Gallipoli peninsula nearly equalled Hamilton’s and the build-up continued. The new Turkish formations despatched to join the two divisions present in Gallipoli were the 5th, 11th and 19th Divisions and two battalions of Gendarmerie.

If the Turks were in any doubt as to the impending attack on Gallipoli it was dispelled by the preparations in Egypt, made under the eyes of a multitude of Turkish spies; the assembly of large and small ships and the embarkation of British, Australian, New Zealand and French troops.

Preparations for the landings on Gallipoli:

The transports carrying the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force sailed from Alexandria and Port Said between 3rd and 22nd April 1915.

D Company (Tasmanian), 12th Battalion, Australian Imperial Force, Egypt 30th December 1914: Gallipoli Part II, March 1915 to January 1916 in the First World War

The Force comprised:

29th Division 17,649 personnel in 15 ships

ANZAC 30,638 personnel in 35 ships

French Division 16,762 personnel in 22 ships

Royal Naval Division 10,007 personnel in 12 ships

Total: 75,056 personnel in 84 ships

On 8th April 1915 General Hamilton and his staff sailed from Alexandria for Mudros in the commandeered Arctic cruise ship Arcadian.

Transport B7 prepares to leave Alexandria with troops and equipment for the Gallipoli landings: Gallipoli Part II, March 1915 to January 1916 in the First World War

General Hamilton directed that the 29th Division was to carry out the main landing along the Cape Helles beaches at the southern end of the Gallipoli Peninsula.

The French contingent under General d’Amade was to land at the eastern end of the Cape Helles beaches on the right of the 29th Division.

During April 1915 the staff of the ANZAC Corps drew up plans for the corps to land on its own Gallipoli beach north of Gaba Tepe. Hamilton decided to adopt this plan. The expectation was that the ANZAC landing would inhibit reinforcement of the Turkish forces facing the main British and French landing at Cape Helles.

Map of the Gallipoli Peninsula. The inset shows the area of Anzac Cove and Suvla Bay: Gallipoli Part II, March 1915 to January 1916 in the First World War

The landing on each beach was divided into two phases, an initial landing by a covering party followed by the main force. The number of men in each phase was governed by several factors; the size of the beach on which the landing was to take place, the availability of naval transports to convey the troops to the area and then to the beach and the number of ships that could safely manoeuvre in the dark off each beach.

At the insistence of Admiral de Robeck it was decided that the troops would make the landings from warships not from the civilian transports that were bringing them to the area. De Robeck’s reasoning was that only naval crews could be relied upon in the crisis of an opposed landing.

The warships would approach the coast in darkness and the troops would be transported to the shore in tows (large unpowered open boats), towed by motor launches and finally rowed to the beach by naval crews.

Commander Unwin RN of HMS Hussar proposed that a collier be beached on ‘V’ Beach at Cape Helles to land the complement of troops that she carried while fire support would be provided by machine guns in the fortified bow area of the collier. The plan was adopted and the collier River Clyde selected. Unwin was given command of the River Clyde and spent the few remaining days equipping the collier for its role. The River Clyde would carry 2,000 troops and tow a number of smaller craft that would be brought forward once the collier was aground to form a bridge to the shore.

The town of Chanak on the Asiatic coast of the Dardanelles, seen after the War: Gallipoli Part II, March 1915 to January 1916 in the First World War

A further addition to the plan was the decision to land a French regiment at Kum Kale on the Asiatic shore to confuse the Turks as to the actual target of the landing and delay the transfer of Turkish troops to the Gallipoli side.

A further feint attack was to be made near to Bulair at the northern end of the Gulf of Saros.

The beaches to be attacked were:

Cape Helles: (from the east) ‘S’, ‘V’, ‘W’ and ‘X’ beaches.

Further north and level with Krithia: ‘Y’ beach.

ANZAC (north of Gaba Tepe): ‘Z’ beach.

The plan was for the landings to take place on 23rd April 1915 or as soon as circumstances and in particular the weather permitted.

A final addition was for one battalion less one company to land at ‘S’ Beach, between Cape Helles and Gaba Tepe. The soldiers in this party would have to row themselves ashore due to the lack of towing motor launches.

The main landings would be on the five beaches at Cape Helles and would begin early in the morning. The initial wave would be of 4,900 men, led by the landing of 2,000 at ‘Y’ Beach.

The next wave would be 2,100 men landing from the River Clyde followed by a further 1,200 brought up by the tows at ‘V’ Beach.

These troops were to secure the beaches in preparation for the main bodies.

The target for the southern landings was to take the hill of Achi Baba and finally the Kilid Bahr plateau.

At ‘Z’ Beach (ANZAC) the covering wave of 4,000 men was to be landed from a flotilla of destroyers with the task of securing the parts of the Sari Bair ridge that overlooked the beach.

The goal of the main ANZAC force was to capture the high ground in the middle of the Gallipoli Peninsula and in particular the hill of Mala Tepe, thereby cutting the road to the south.

In the eight months that the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force was ashore on the Gallipoli Peninsula and in spite of intense fighting none of these main goals was achieved.

Air Support:

At the end of March 1915 Number 3 Squadron Royal Navy Air Service arrived in the theatre and was able to provide a degree of air support. There were however no cameras available for reconnaissance for a further two weeks and observers had to be recruited from volunteers who learnt the trade ‘on the job’.

The aircraft operated from the Island of Tenedos, the nearest runway. The Anzac landing was too far from Tenedos and relied on a balloon flown from a kite ship.

French troops training on the Greek Island of Lemnos before leaving for the landing on the Gallipoli Peninsula: Gallipoli Part II, March 1915 to January 1916 in the First World War

Departure from Mudros:

The armada of warships and transports in Mudros harbour suffered significant problems. One of the most awkward was the inability to communicate between ships to plan for the landing. Bad weather and the lack of steam motorboats severely hampered movement between ships. Wireless communication was not generally available and there was no other viable form of signal.

Mudros harbour on the Island of Lemnos, base for the British and French operations against the Turks on the Gallipoli Peninsula: Gallipoli Part II, March 1915 to January 1916 in the First World War

Bad weather prevented the force from sailing until 23rd April 1915 when good weather set in.

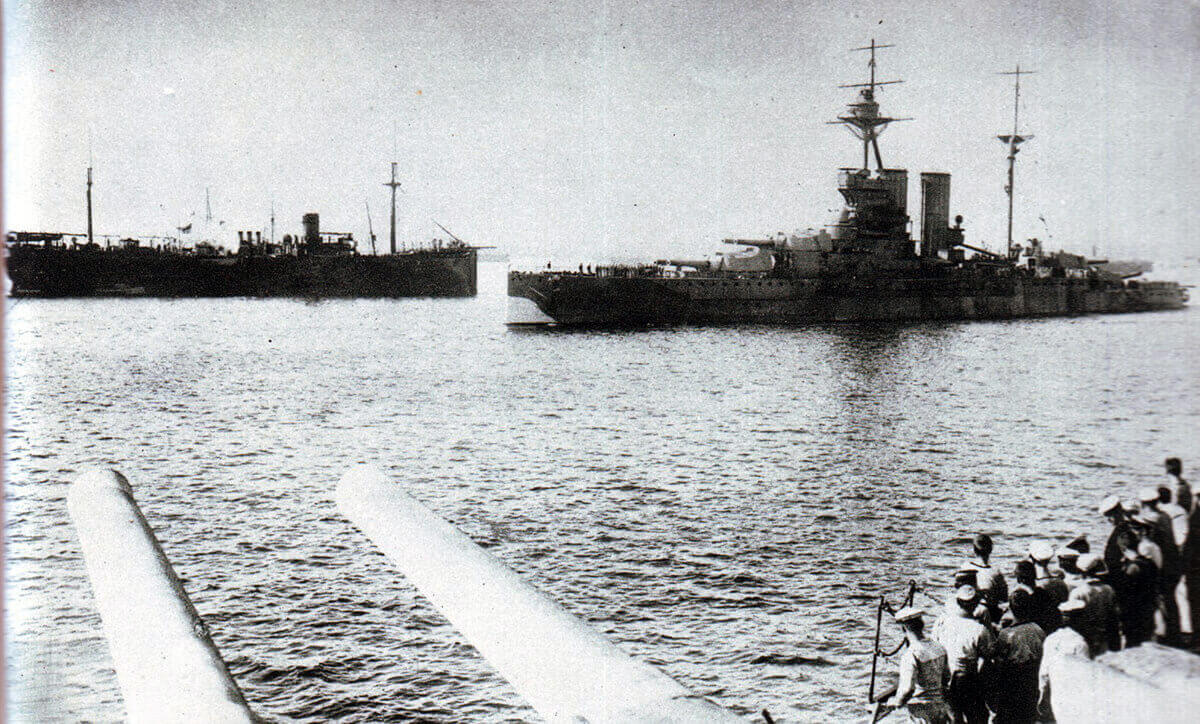

On 24th April General Hamilton sailed for Gallipoli with Admiral de Robeck on board the flag ship HMS Queen Elizabeth and the rest of the force sailed for Gallipoli.

HMS Queen Elizabeth, the British flag ship, leaving Mudros on the Greek Island of Lemnos for the Gallipoli landings on 24th April 1915: Gallipoli Part II, March 1915 to January 1916 in the First World War

Turkish dispositions on the Gallipoli Peninsula:

General Eric Liman von Sanders, the German officer given command of the Turkish troops on the Gallipoli Peninsula

On 24th March 1915 the Ottoman War Minister, Enver Pasha, directed that the Turkish force on the Gallipoli Peninsula be formed into a single Army with the German officer, General Liman von Sanders, as its commander.

Liman von Sanders distributed his forces with the Turkish 5th and 7th Divisions in the area of Bulair at the north-eastern end of the Gallipoli Peninsula, which von Sanders considered the most threatened point, the Turkish 9th Division holding the Gallipoli Peninsula from Suvla Bay in the middle of the peninsula to Cape Helles at the south-western tip, including ANZAC cove. The Turkish 3rd Division held the Asiatic shore. The 19th Division, commanded by Mustapha Kemal, later Head of the post-War Turkish State, constituted the general reserve at Boghali.

The Turkish 9th Division, holding the key southern half of the Gallipoli Peninsula, was distributed with the 27th Regiment and two mountain batteries in the northern zone, which included Anzac Cove, and the 26th Regiment with one mountain battery in the southern zone, which included Cape Helles. The 25th Regiment, on the Kilid Bahr plateau, formed the divisional reserve.

The 9th Division regiments were further disposed so that the troops immediately defending the main landing points on the coast amounted to around one company per beach with one or two machine guns, although substantial reinforcements were in the hills close by.

In the last month before the landings Liman von Sanders put the Turkish infantry through a rigorous training program to overcome the lethargy of inactive garrison duty, involving marching, shooting and the novel use of trench bombs (hand grenades). At nights the Turkish troops were set to work digging trenches and building strong points.

The month that elapsed between the end of the naval bombardment on 18th March 1915 and the British and French landings on 25th April 1915 was just sufficient for Liman von Sanders to knock his Turkish troops into shape and prepare his defences, although the build-up of troops, their training and the digging of entrenchments was a continuing process throughout 1915, sufficient to keep ahead of the British and French supply of reinforcements and new equipment.

Turkish troops being instructed in the use of the German service rifle: Gallipoli Part II, March 1915 to January 1916 in the First World War

Diversion at Bulair on 25th and 26th April 1916:

On 25th and 26th April 1915 British and French warships bombarded the Bulair Isthmus at the north-eastern end of the Gallipoli Peninsula and conducted simulated landings. Liman von Sanders was thereby confirmed in his belief that this was the main British and French attack, causing him to hold back reinforcements that would otherwise have been sent to assist the Turkish units in the south of Gallipoli.

As part of this demonstration Lieutenant Commander Bernard Freyberg swam ashore at Bulair and set off flares along the coast before swimming back to his cutter.

In the meantime the real landings were taking place at Anzac and Cape Helles in the south of the Gallipoli Peninsula.

Rupert Brooke:

Rupert Brooke the poet was a sub-lieutenant in the Hood Battalion of the Royal Naval Division. Brooke served with the Division at Antwerp in October 1914 before sailing with his unit to join the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force.

Brooke died of an infected mosquito bite on a French ship on 23rd April 1915 on his way to the Gallipoli landings. He was buried on the Greek Island of Skyros.

Rupert Brooke, as a sub-lieutenant in the Hood Battalion of the Royal Naval Division, with his mother

The Soldier

If I should die, think only this of me:

That there’s some corner of a foreign field

That is for ever England. There shall be

In that rich earth a richer dust concealed;

A dust whom England bore, shaped, made aware,

Gave, once, her flowers to love, her ways to roam,

A body of England’s, breathing English air,

Washed by the rivers, blest by suns of home.

And think, this heart, all evil shed away,

A pulse in the eternal mind, no less

Gives somewhere back the thoughts by England given;

Her sights and sounds; dreams happy as her day;

And laughter, learnt of friends; and gentleness,

In hearts at peace, under an English heaven

Rupert Brooke

References for the Gallipoli Landings:

Times History of the First World War

Official History of Military Operations in Gallipoli by Brigadier Aspinall-Oglander

‘Mr Midshipman VC’: biography of Midshipman George Drewry, winner of the Victoria Cross during the landings from the River Clyde on 25th April 1915 at Gallipoli; written by Quentin Falk and published by Pen and Sword Maritime in 2018.

The previous battle of the First World War is Gallipoli Part I: Naval Attack on the Dardanelles

The next battle of the First World War is Gallipoli Part III: ANZAC landing on 25th April 1915