The Titanic struggle between the British Grand Fleet and the German High Seas Fleet on 31st May 1916

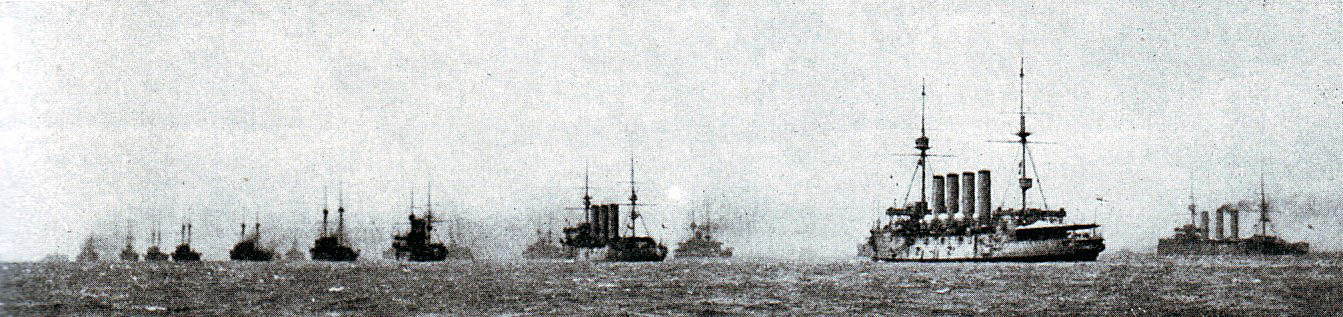

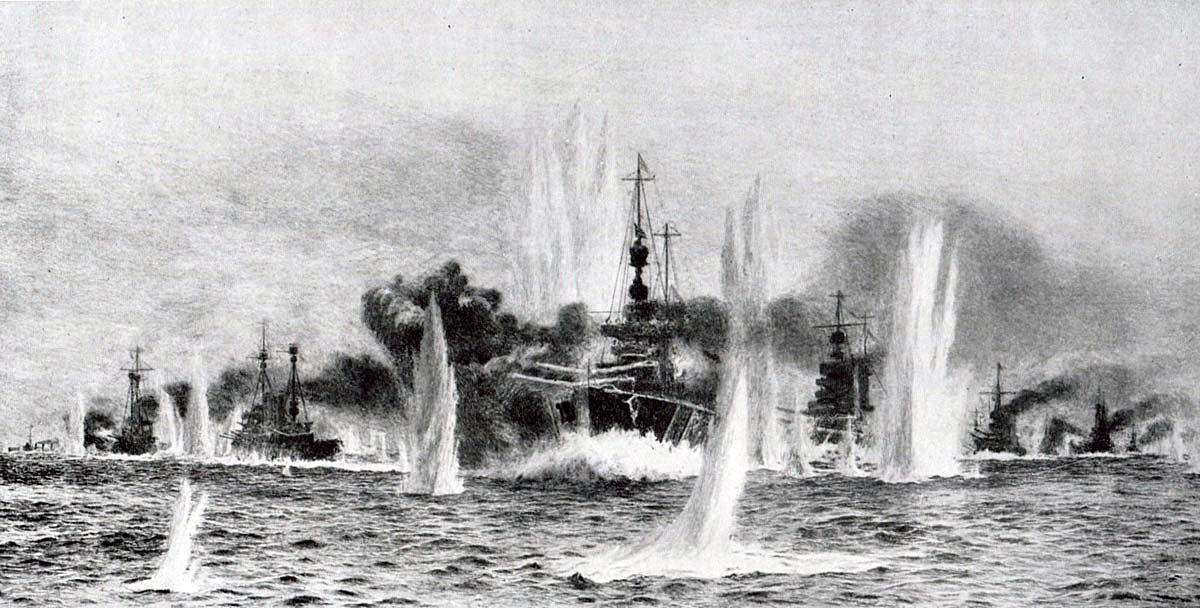

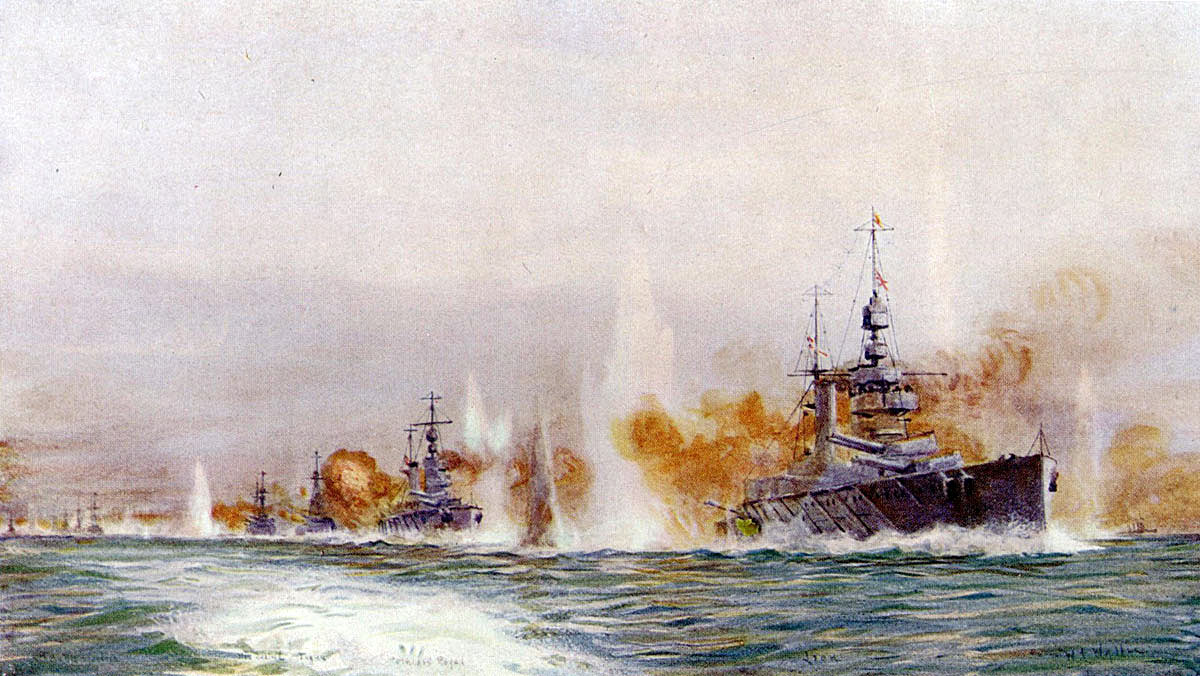

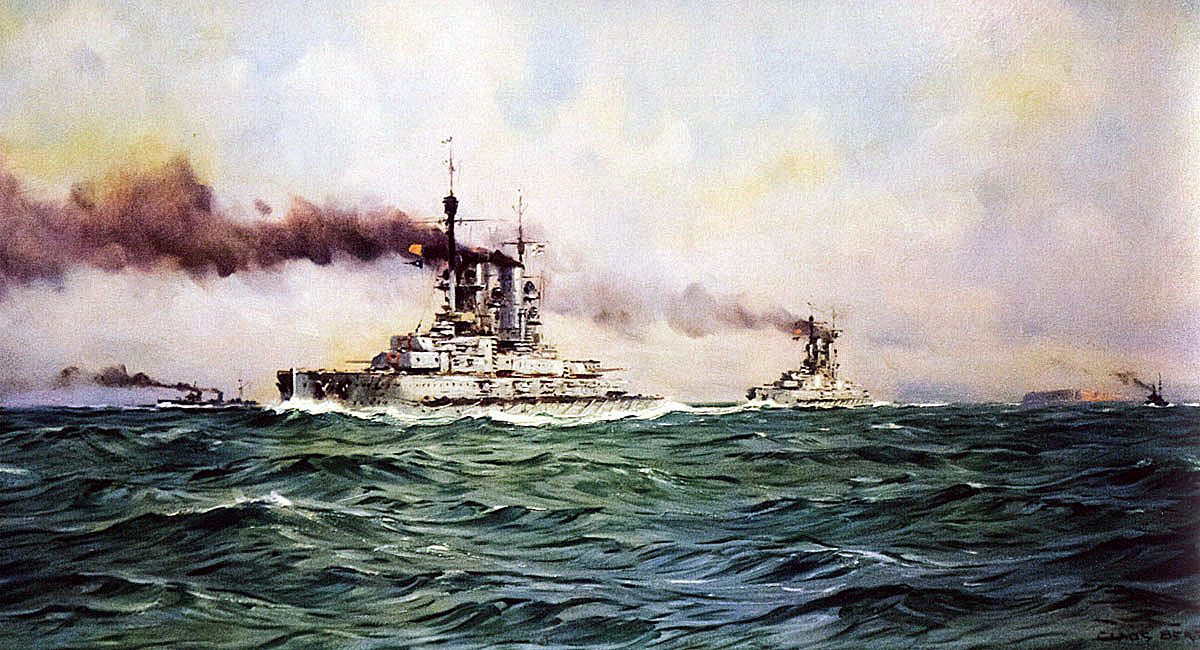

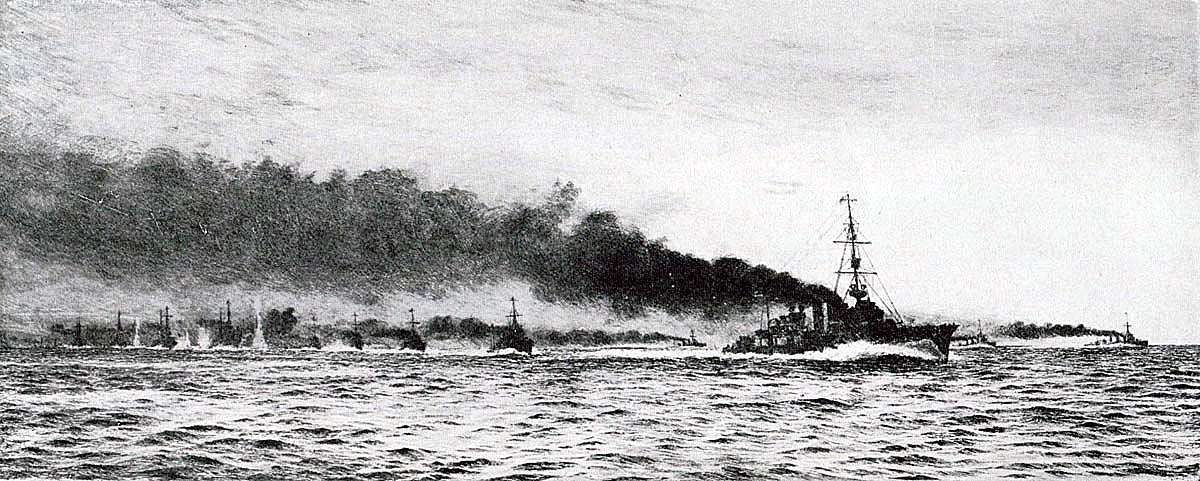

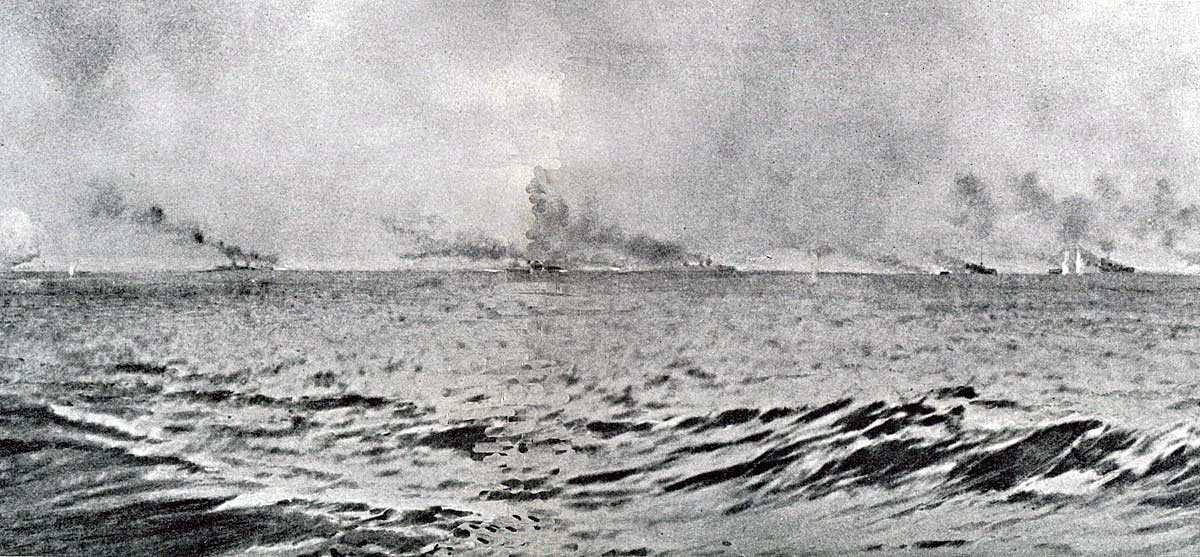

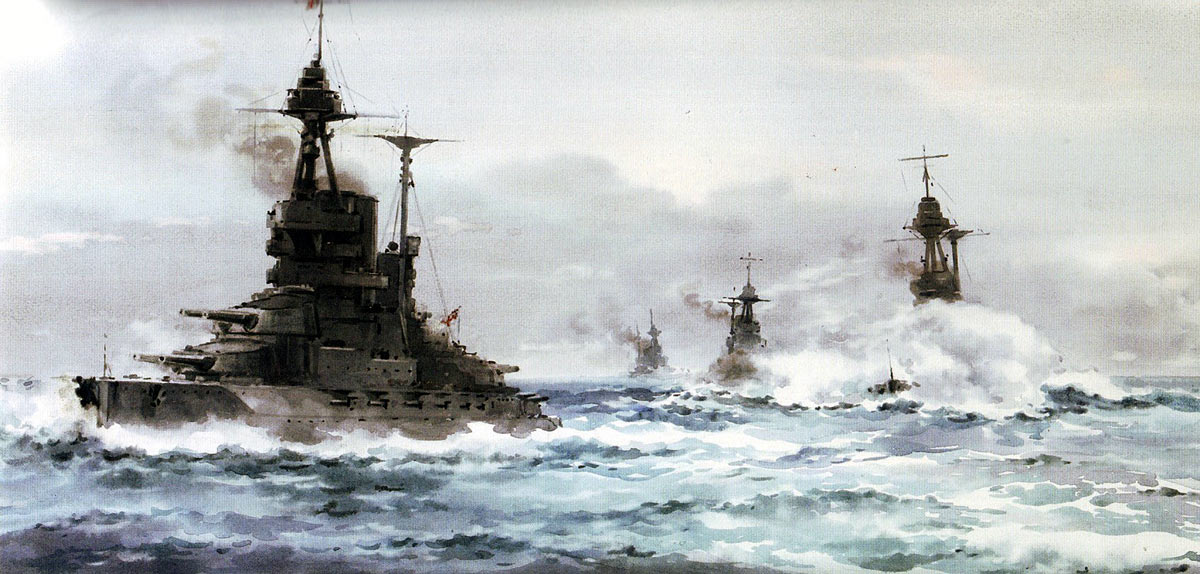

British Battle Cruisers opening fire in the opening stages of the Battle of Jutland on 31st May 1916: from the right HMS Lion Princess Royal Tiger Queen Mary New Zealand and Indefatigable: picture by Lionel Wyllie

The previous battle of the First World War is the Battle of Jutland Part I

The next battle of the First World War is the Battle of Jutland Part III

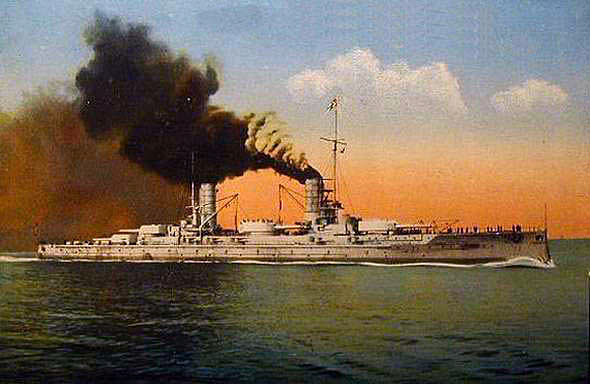

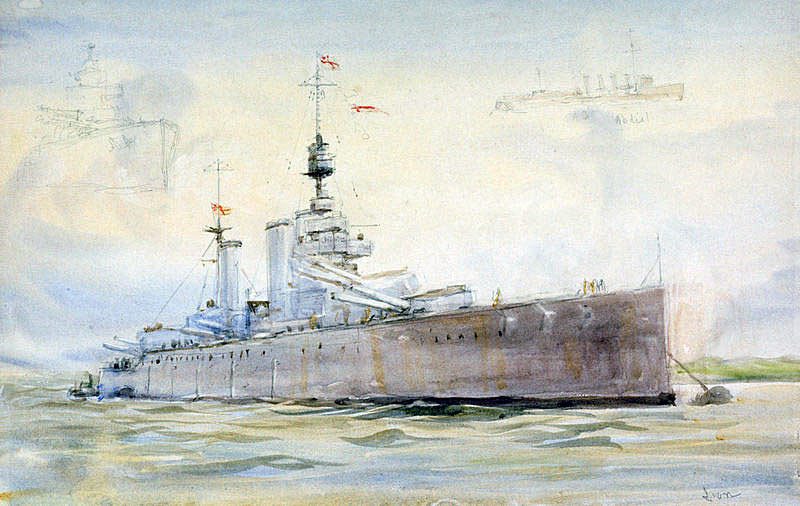

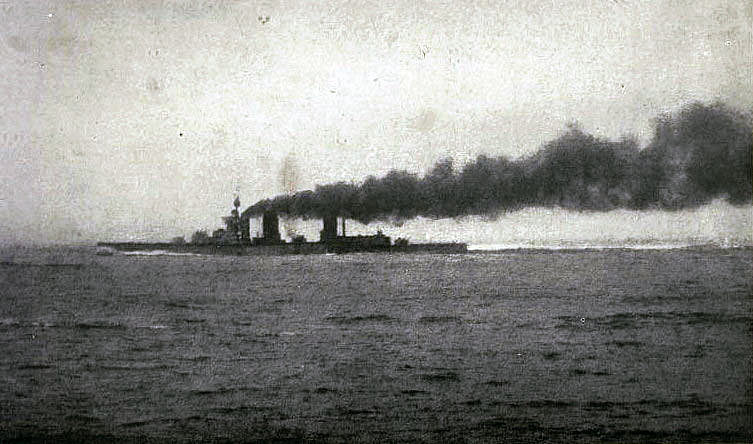

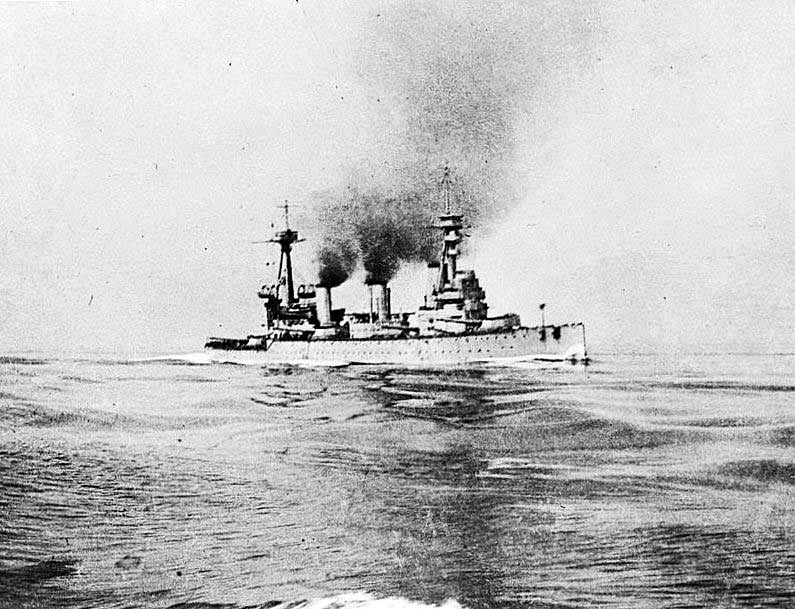

British Battle Cruiser HMS Lion. Lion was Admiral Beatty’s Flagship at the Battle of Jutland 31st May 1916: picture by Lionel Wyllie

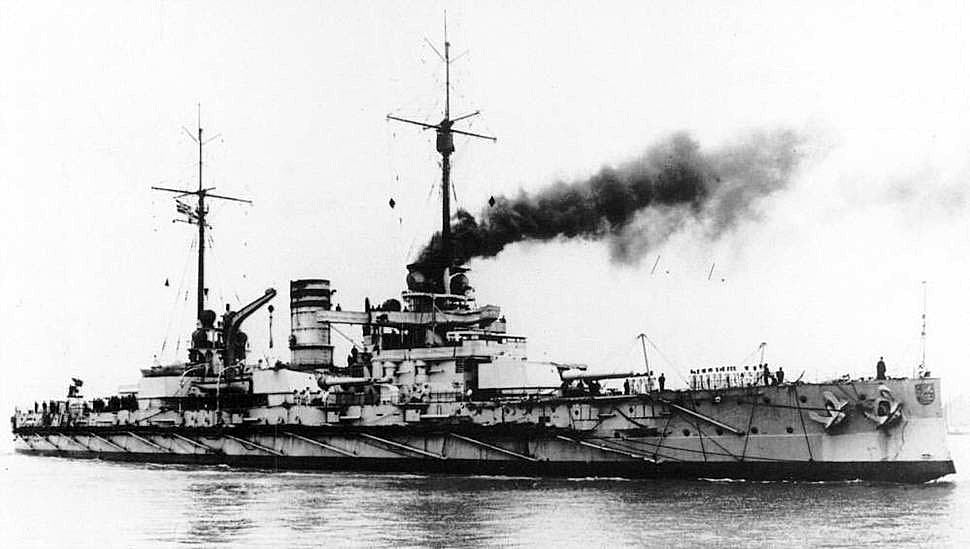

British Battle Cruiser HMS New Zealand. New Zealand fought in the Battle of Jutland on 31st May 1916

Vice-Admiral Sir David Beatty commanding the British Battle Cruiser Fleet at the Battle of Jutland 31st May 1916

Battle: Jutland

Date: 31st May 1916

Place: In the North Sea off the coast of Denmark

War: The First World War

Contestants: The British Royal Navy against the Imperial German Navy

Admirals: Admiral Sir John Jellicoe commanded the Royal Navy’s Grand Fleet. Vice Admiral Sir David Beatty commanded the British Battle Cruiser Fleet. Admiral Reinhard Scheer commanded the German High Seas Fleet. Vice Admiral Franz Hipper commanded the German Battle Cruiser Squadron.

Winner:

The German navy considered it won the Battle of Skagerrak , the German name for Jutland, having sunk more Royal Navy ships and inflicted more casualties. The Royal Navy considered that it had repelled the incursion by the High Seas Fleet into the North Sea. The German fleet made only one further incursion during the War.

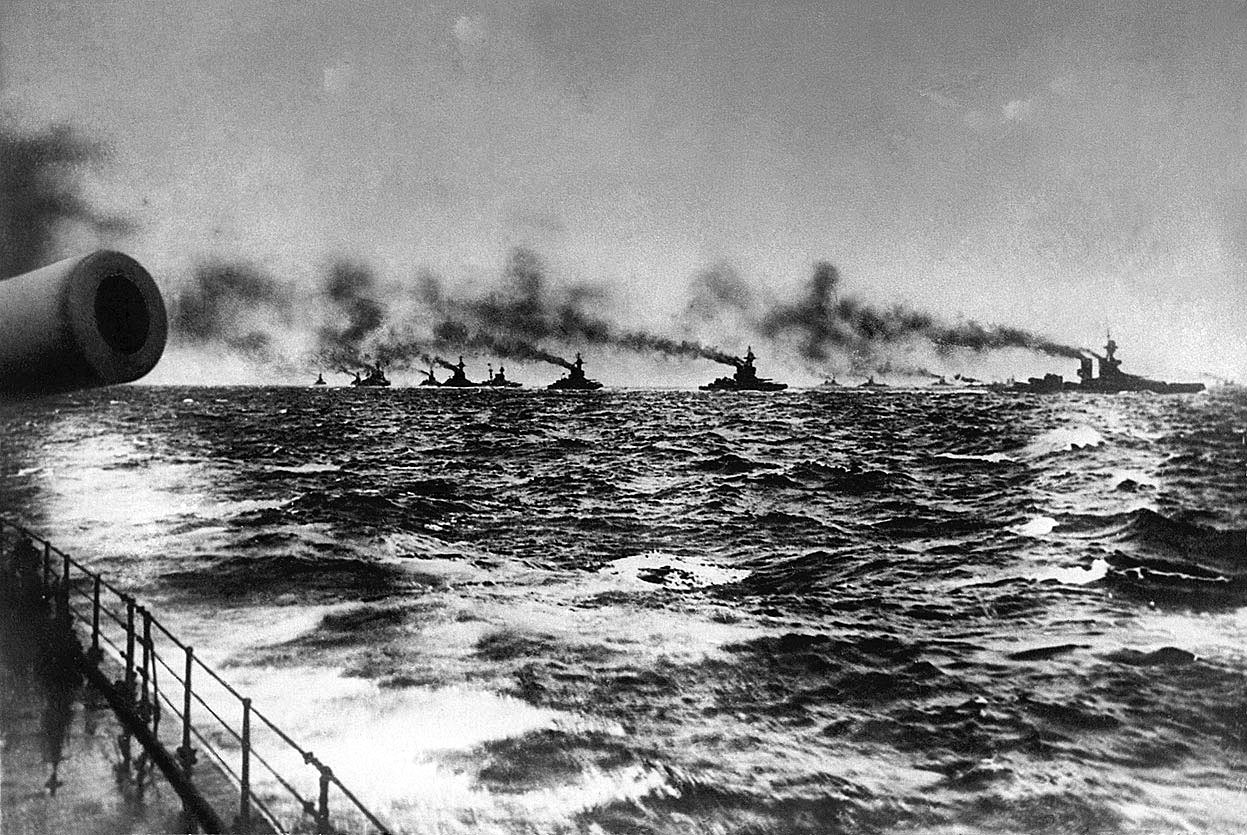

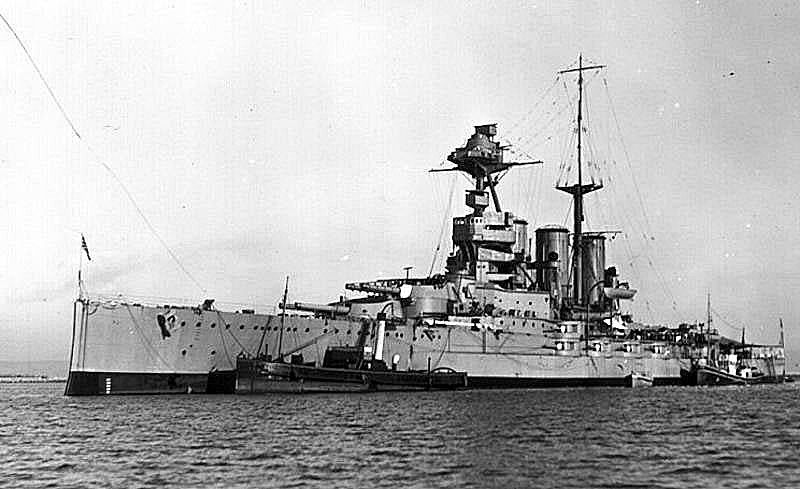

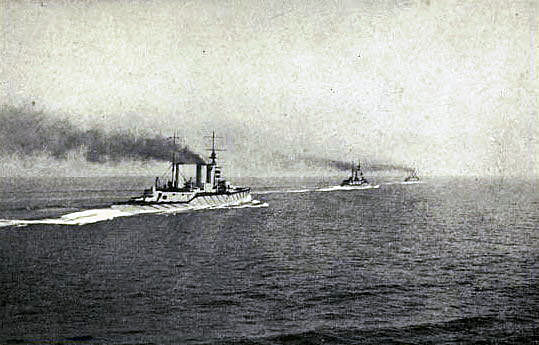

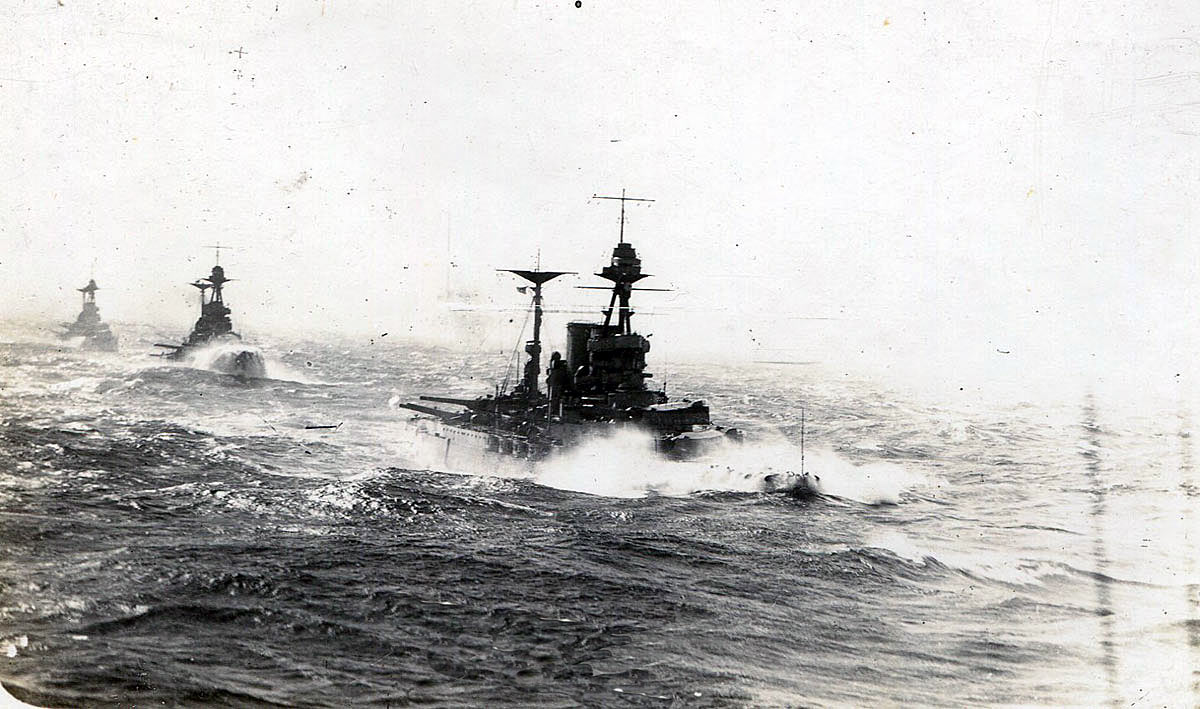

British Battle Cruisers HMS Tiger Princess Royal and Lion 1916: contemporary photograph taken from the next battle cruiser in line possibly Queen Mary

The Battle of Jutland Part II: the opening Battle Cruiser actions on 31st May 1916

Background:

From the beginning of the First World War the Royal Navy’s Grand Fleet was stationed at Scapa Flow in the Orkneys and Rosyth in the Firth of Forth waiting for the German High Seas Fleet to emerge from its network of naval bases along Germany’s short North Sea coast.

A strong Royal Navy force, comprising light cruisers, destroyers and submarines stationed at Harwich kept a direct watch on the German bases.

From late 1914 the German navy conducted a series of hit and run raids on coastal towns in north-east England. Admiral Jellicoe the commander-in-chief of the Grand Fleet was expected to curtail these raids. There was also an expectation that the Grand Fleet would bring the German High Seas Fleet to battle and defeat it. This required the High Seas Fleet to emerge from its bases.

Other units of the Royal Navy imposed a blockade on the ports of the central powers, Germany and Austria. In answer to this blockade at the beginning of 1915 the German navy began unrestricted submarine warfare in an attempt to destroy British and French trade.

On 7th May 1915 the German submarine U20 sank the RMS Lusitania causing the deaths of 128 US citizens. Following the international and American outcry Germany abandoned her policy of unrestricted submarine warfare (it was resumed in 1917). This made the German submarine force available to act with the High Seas Fleet in any foray into the North Sea.

Admiral Scheer the commander of the High Seas Fleet was keen to act offensively. It is said that German national morale was suffering due to the losses in the land offensive against the French at Verdun and that there was widespread dissatisfaction in the German Army and across the country at the perceived inactivity of the Kaiser’s much vaunted expensive and powerful surface navy.

In May 1916 Admiral Jellicoe began planning a scheme to entice the German High Seas Fleet out to sea at the beginning of June. Co-incidentally Admiral Scheer was planning a reverse of this plan to lure out and destroy powerful units of the Grand Fleet at the end of May 1916. Scheer’s timing was governed by the need to await completion of repairs to the battle cruiser SMS Seydlitz.

The precise details of Scheer’s plan are not clear. It would seem that Scheer’s intention was to cross the North Sea and bombard the English coastal town of Sunderland with a small force of battle cruisers followed at a distance by the full German High Seas Fleet. Beatty’s battle cruisers would be drawn down from Rosyth giving the waiting battleships of the German High Seas Fleet the opportunity to sink some or all of Beatty’s ships before they could be reinforced by Jellicoe’s battleships from Scapa Flow in the Orkneys.

A line of fifteen U boats took up positions off British bases down the east coast to intercept British surface ships as they went to sea to meet the German High Seas Fleet and also laid mines in coastal waters. The British Admiralty was aware of the presence of these submarine.

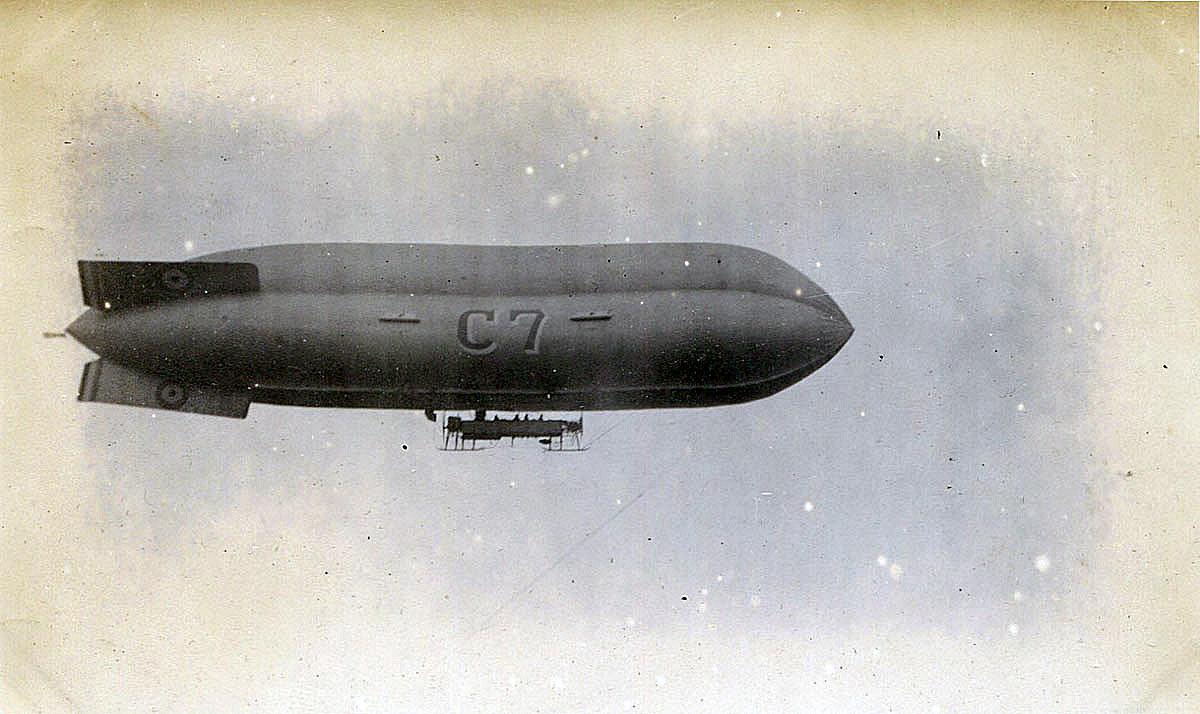

Reconnaissance by Airships was expected to warn Scheer if Jellicoe’s battle squadrons, in the habit of conducting unpredictably timed sweeps down the North Sea, took to sea at an inconvenient time.

An alternative plan was for the German battle cruisers to sail up the Danish coast to the Skagerrak acting as a bait to lure Beatty’s battle cruiser fleet to action so that it could be destroyed by the battleships of the German High Seas Fleet following out of sight.

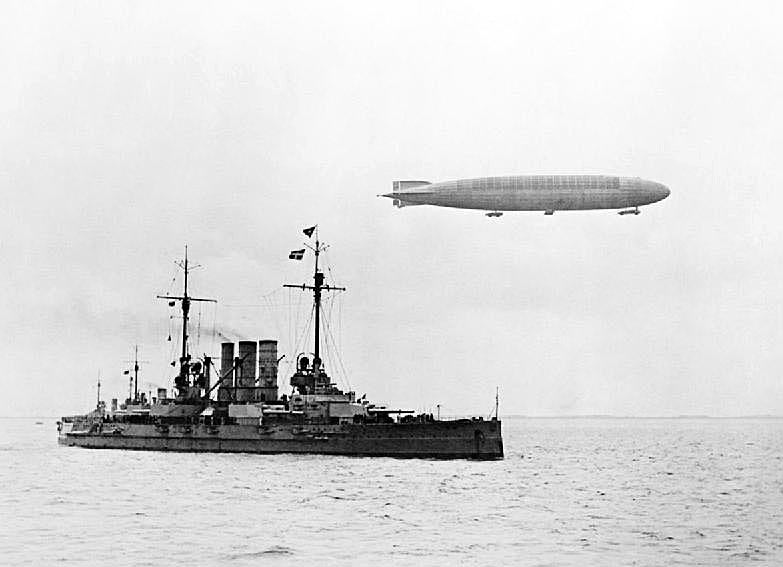

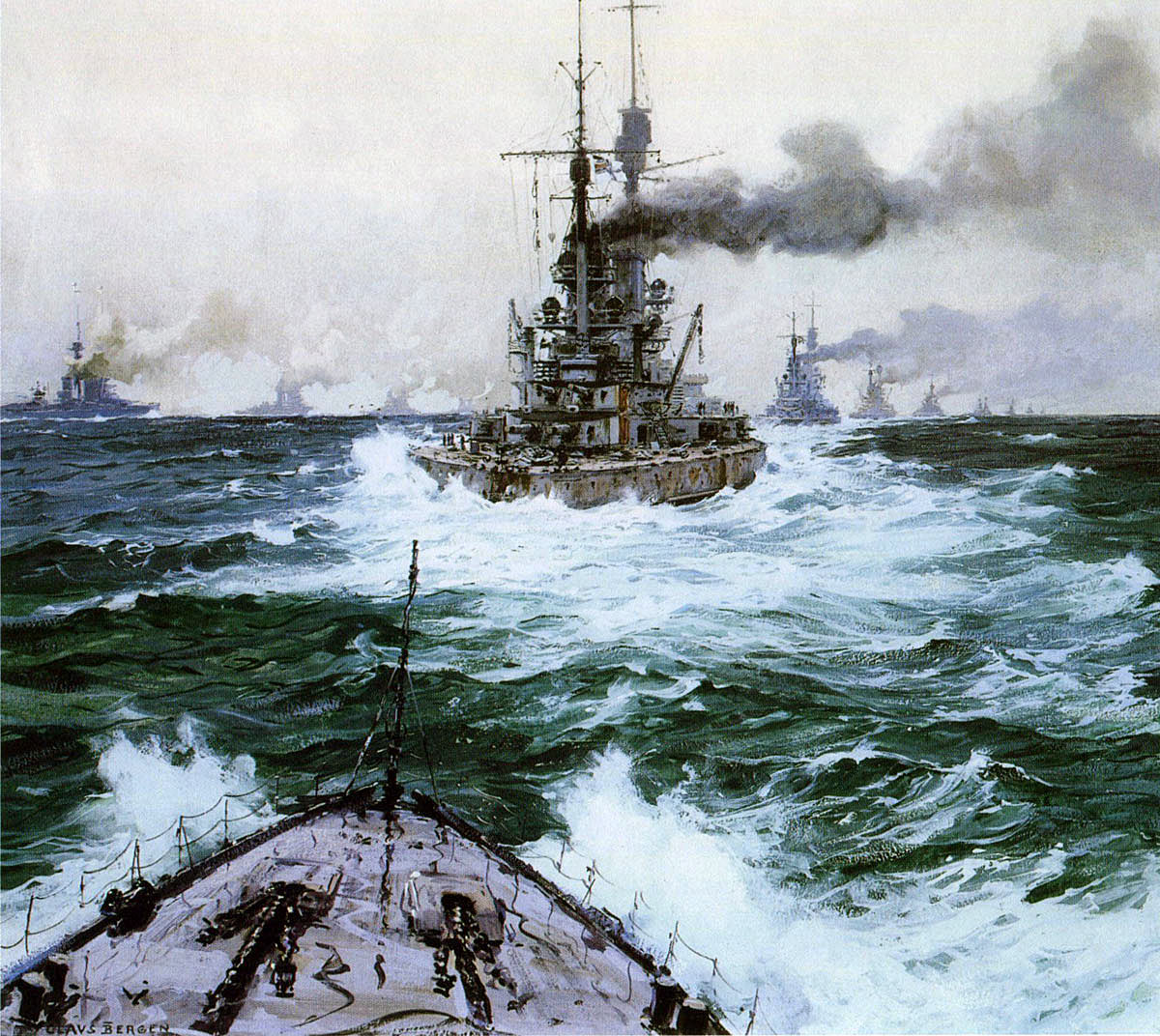

German High Seas Fleet passing Heligoland on 30th May 1916 as it steamed into the North Sea to ambush Admiral Beatty’s battle cruisers leading to the Battle of Jutland: picture by Claus Bergen

30th May 1916:

Airships required near wind-free conditions to fly. With the weather remaining bad and consequently lacking the necessary aerial reconnaissance, on 30th May 1916 Admiral Scheer gave orders for the alternative Skagerrak operation to begin the following day. Admiral Hipper would take his First Scouting Group Battle Cruisers along the Norwegian coast to be seen by the British light cruisers and submarines in the area in the expectation that this would bring Beatty’s Battle Cruiser Fleet across the North Sea.

First Battle Cruiser Squadron leaving the Firth of Forth for the Battle of Jutland: picture by Lionel Wyllie

The subterfuge was misconceived. By 5pm on 30th May 1916 Room 40 at the British Admiralty was able partially to decode a wireless signal sent to all the ships of the High Seas Fleet. It was clear that a major German operation was under way and that several ships were already in the Jade Roads after leaving harbour. Jellicoe was warned and the Harwich destroyers and mine sweeping sloops recalled to harbour.

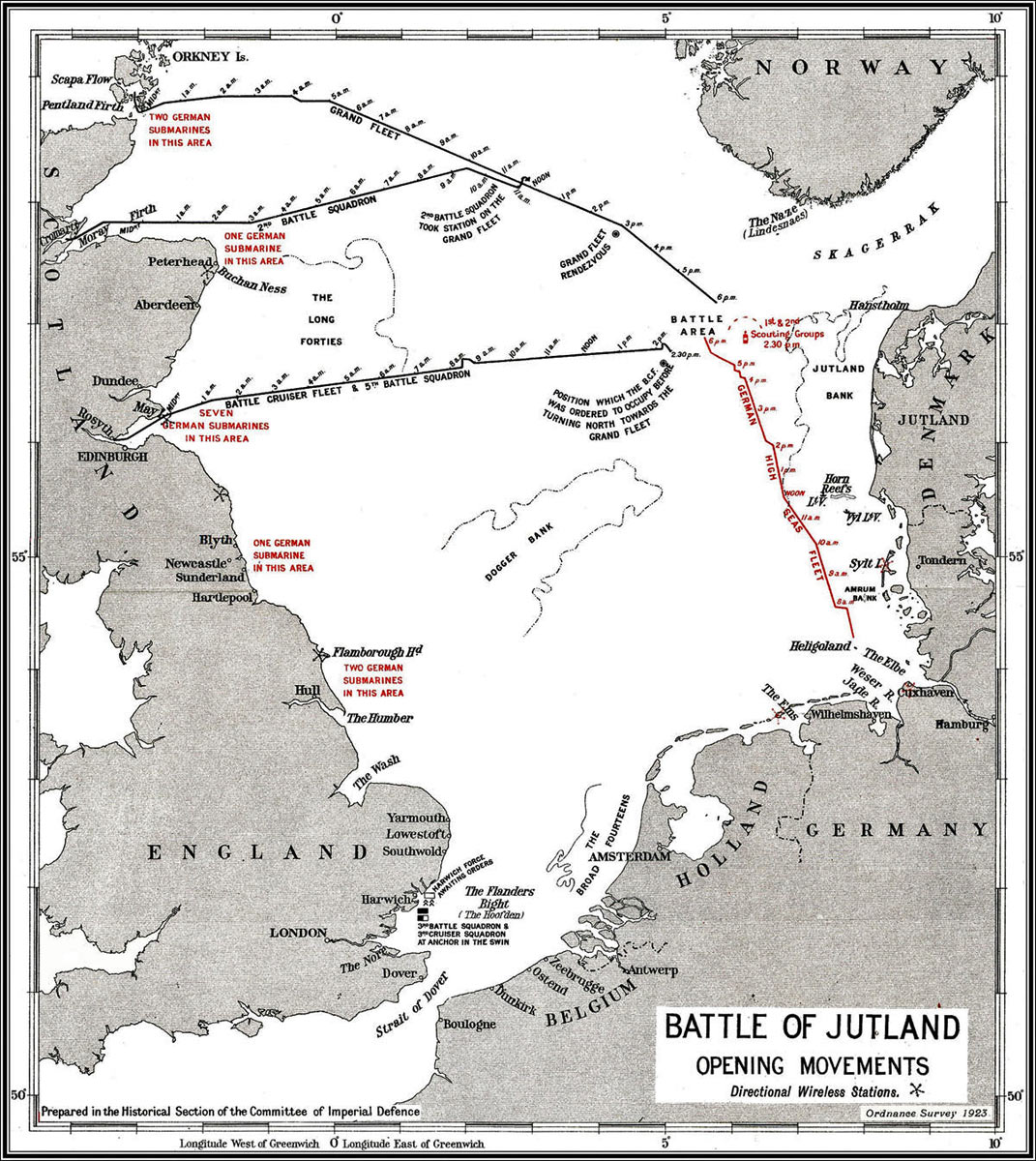

Map of the North Sea showing the advance of the British and German Fleets to the Battle of Jutland on 31st May 1916

At 5.40pm the British Admiralty sent telegrams to Beatty and Jellicoe ordering them to leave harbour and concentrate at the east of the ‘Long Forties’ the designated rendezvous for dealing with a possible German incursion into the northern area of the North Sea. Appropriate orders were sent to the commands further south on the eastern coast.

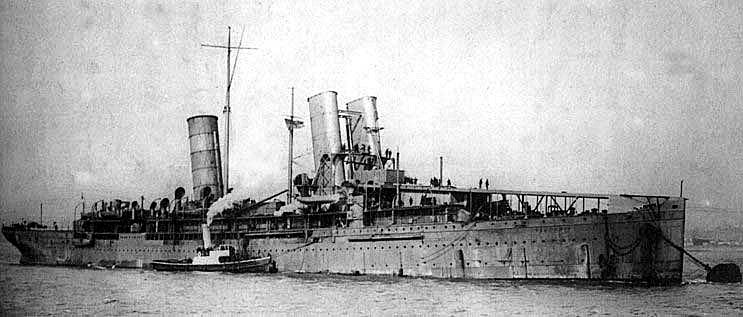

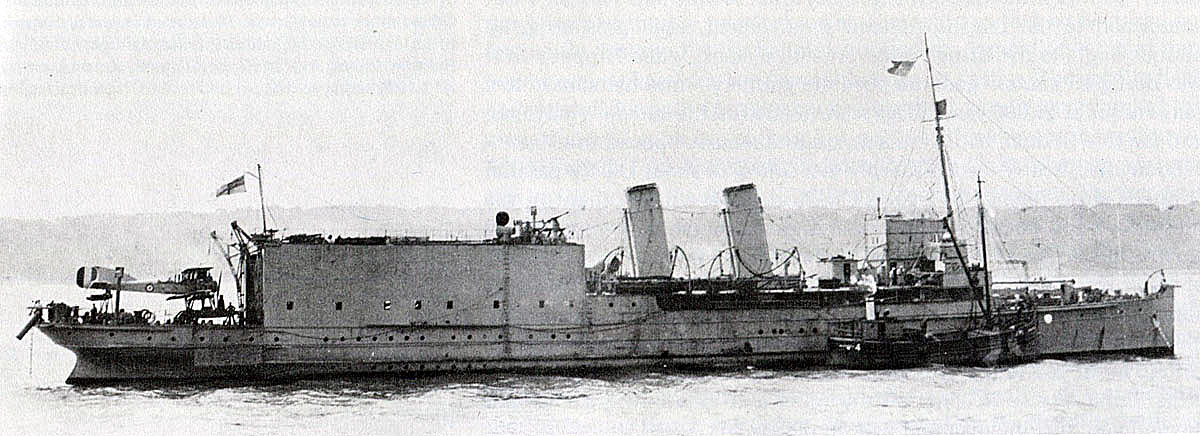

The Grand Fleet (see the order of battle of both fleets in Part I) sailed from Scapa Flow at around 9.45pm on 30th May 1916. Due to a failure to receive the order to sail the fleet seaplane carrier HMS Campania, which had been out on exercise, left two and a quarter hours later and consequently in Jellicoe’s view was too far behind to take an active part in the battle. She was ordered to return to Scapa Flow.

HMS Campania Admiral Jellicoe’s Seaplane Carrier left behind when the Grand Fleet sailed for the Battle of Jutland 31st May 1916

In fact Campania was overhauling the Grand Fleet and would have reached her before the battle began. Her ten seaplanes might have rendered valuable assistance to Jellicoe in tracking the elusive German High Seas Fleet, particularly in the early dawn hours of 1st June. They could also have prevented the German airships from keeping track of the Grand Fleet at that time.

Jellicoe’s rendezvous was off the Norwegian coast. Beatty was heading to a point some 70 miles to the south-east of the Grand Fleet rendezvous and nearer to the German coast, with his force of 1st and 2nd Battle Cruiser Squadrons, 5th Battle Squadron less HMS Queen Elizabeth which was ‘in dockyard hands’, 1st, 2nd and 3rd Light Cruiser Squadrons and 27 destroyers.

While Beatty’s force had the general role of providing advanced reconnaissance for the Grand Fleet it was primarily required to prevent any raid on the British coast-line.

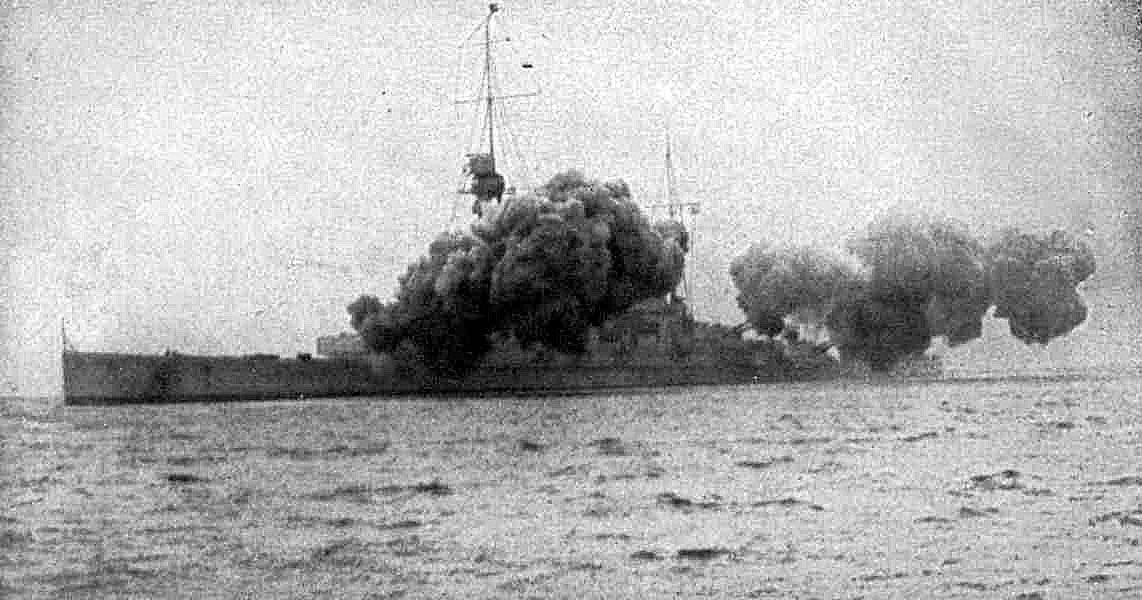

German Battle Cruiser SMS Lützow opens fire in the opening minutes of the Battle of Jutland on 31st May 1916

This was the system established during the numerous patrols conducted by the Royal Navy in the North Sea up to this time. There was as yet insufficient information that the situation was any different from earlier occasions when Hipper’s fast battle cruisers acting alone carried out hit and run raids on English coastal towns.

During the afternoon and evening of 30th May 1916 several British ships reported having torpedoes fired at them as they left harbour but none were hit. The German U Boat ambush had failed and the British ships were at sea.

Both sides still experienced uncertainty. The German U Boat line failed to identify that the Grand Fleet had put to sea and the German procedure of transferring the commander in chief’s call sign to a shore establishment and taking on a new call sign for sea operations caused Room 40 at the British Admiralty to believe that Scheer himself was still in harbour when he and his fleet were well out to sea.

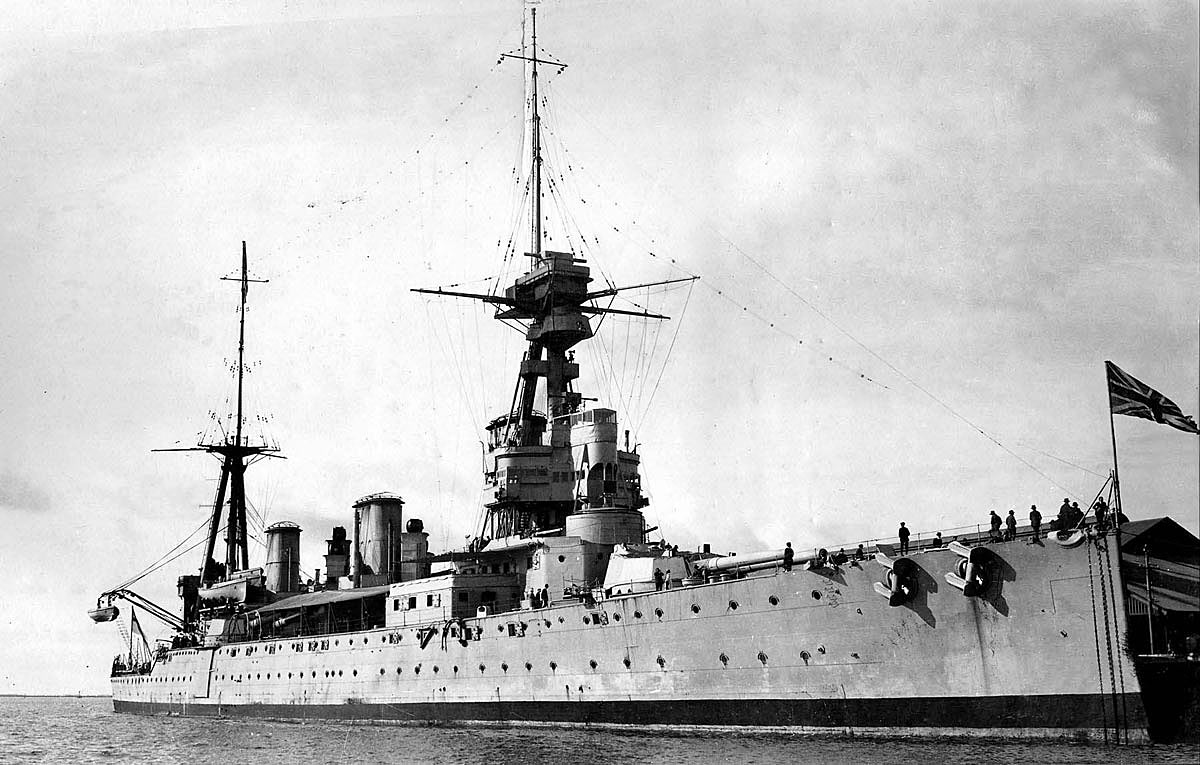

British Battle Cruiser HMS Tiger. Tiger fought in 1st Battle Cruiser Squadron at the Battle of Jutland on 31st May 1916

The British ships expected their deployment to be the usual uneventful routine patrol and the Germans expected to have only Beatty’s battle cruisers to deal with whereas in fact the full fleets of each naval power were rushing to meet each other off the coast of Denmark.

The mistake over Scheer’s call sign continued to lead Room 40 to believe that the High Seas Fleet flagship was still in harbour throughout 30th May 1916. This information was passed to Jellicoe who maintained a moderate steaming speed towards the Jutland Bank in order to conserve his destroyers’ fuel. In fact the High Seas Fleet was on its way to the area.

If Jellicoe had been aware that the High Seas Fleet was well out to sea and had sailed at a greater speed the clash between the fleets would have taken place earlier giving the British more daylight to maintain the action with a corresponding increase in damage inflicted.

British battle cruisers HMS Queen Mary Princess Royal and Lion around 1pm on 31st May 1916 about 2 hours before the Battle of Jutland began: contemporary photograph taken from HMS Tiger the next battle cruiser in line

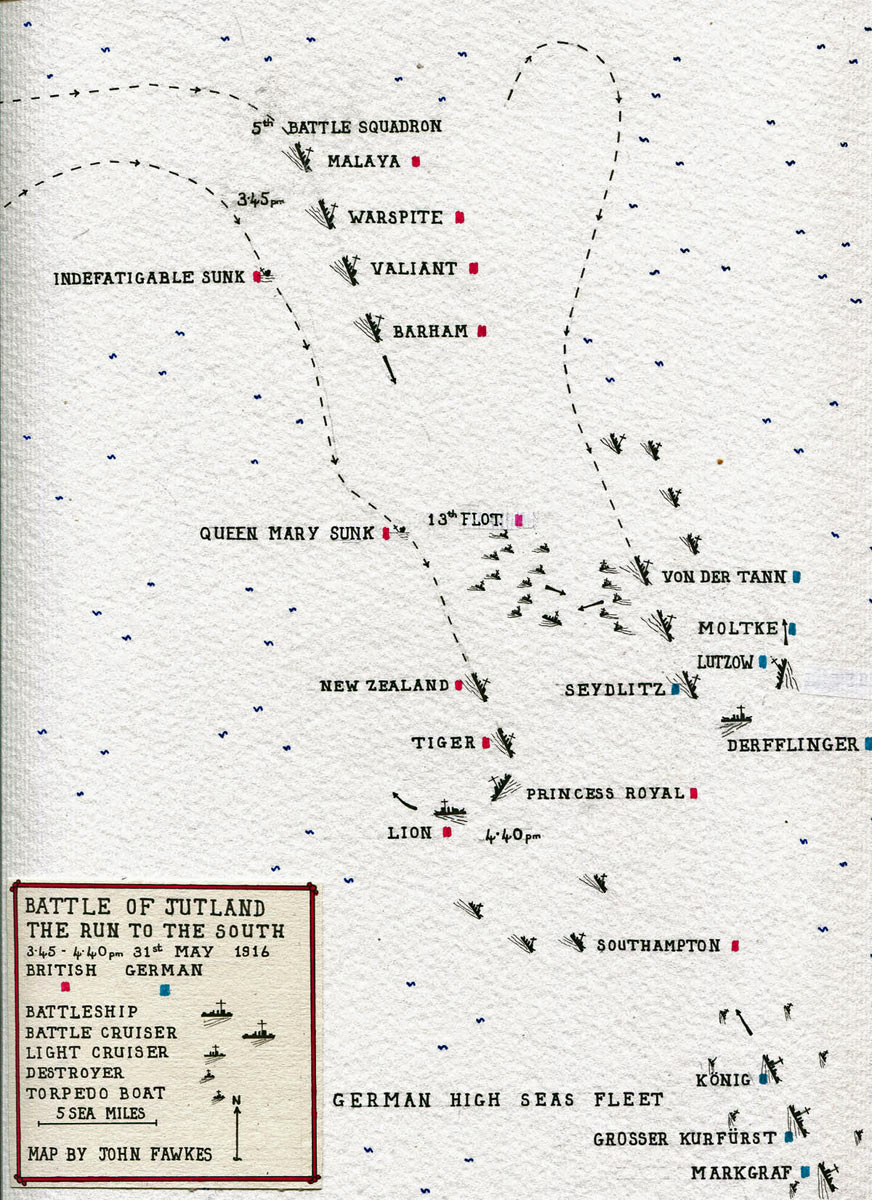

At midday on 31st May 1916 Beatty with 1st Battle Cruiser Squadron (Lion, Tiger and Queen Mary) was near his rendezvous some forty-five miles west of the Jutland Bank. The destroyers formed a screen on each side, the light cruisers were in pairs eight miles to the front, the 2nd Battle Cruiser Squadron (New Zealand and Indefatigable) was three miles away on his port bow and the 5th Battle Squadron (Barham, Valiant, Warspite and Malaya) with 1st Destroyer Flotilla five miles astern.

German Battle Cruiser SMS Lützow Admiral Hipper’s Flagship in the 1st Scouting Group at the Battle of Jutland 31st May 1916. Lützow was sunk during the battle

Beatty signalled his force to begin a turn to the north at 2.15pm on the basis that no German force was at sea (the Admiralty still believed that Scheer’s call sign was in harbour) to meet Jellicoe’s Grand Fleet which was steaming south-east from Scapa Flow towards the rendezvous.

German battle cruisers SMS Seydlitz and von der Tann turning to attack in the opening stages of the Battle of Jutland 31st May 1916

In fact Hipper’s force 1st Scouting Group Battle Cruisers (Lützow, Derfflinger, Seydlitz, Moltke, von der Tann and accompanying light cruisers and destroyers) was fifty miles to the east on the same latitude as Beatty. The light cruisers were in a wide arc, but the nearest ship was still some twenty-two miles from the British.

Scheer’s main force of the High Seas Fleet was following fifty miles behind Hipper. Both fleets were steaming towards each other each unaware of the other’s presence.

Scheer had been persuaded by Rear-Admiral Mauve against his original intention to bring Mauve’s 2nd Battle Squadron of six Pre-Dreadnought battleships; SMS Deutschland, Hannover, Pommern, Schlesien, Schleswig-Holstein and Hessen, in spite of their weak armament, inadequate armour and slow speed.

Shortly before midday five German airships were sent up to conduct a reconnaissance but due to the hazy weather could see little and failed to identify the British ships, returning to their base at 4pm.

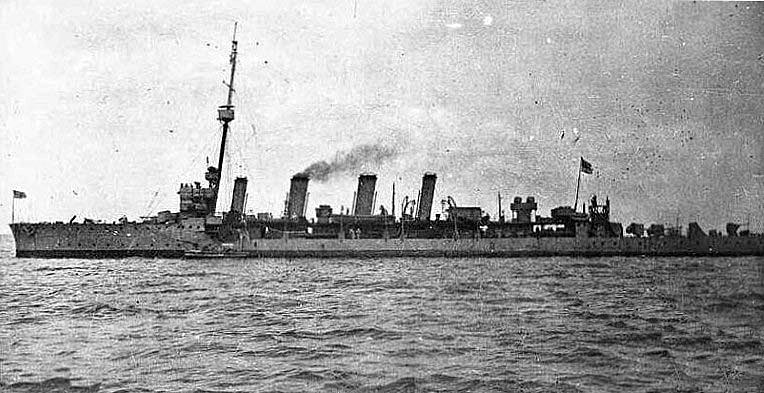

British Light Cruiser HMS Galatea. Galatea fought at the Battle of Jutland on 31st May 1916 as the lead of the 1st Light Cruiser Squadron

At 2pm the incident occurred that triggered the clash between the two fleets. A Danish steamer the ‘Fjord’ was spotted nearly simultaneously by the German light cruiser Elbing and the Royal Navy light cruiser Galatea (the squadron commander Commodore Alexander-Sinclair was on board Galatea) as Beatty’s force was turning onto its northern course. Elbing detached a destroyer to investigate the strange ship as Galatea with Phaeton approached on the same mission. The German destroyer reported seeing Galatea’s smoke and other German light cruisers turned towards the area, Frankfurt, Pillau and Wiesbaden. Galatea signalled at 2.20pm ‘Enemy in sight…’ increased speed towards the German ships and at 2.28pm opened fire.

The Race to the south:

At 2.32pm Beatty ordered his ships to alter course from north to south south-east and raise steam for full speed. The opening phase of the Battle of Jutland known as ‘the Race to the South’ was under way.

Jellicoe’s Grand Fleet was behind schedule due to the despatch of destroyers to investigate suspicious vessels during the journey from Scapa Flow and the need to slow down to allow the tasked destroyers to re-join. Jellicoe was sixty-five miles north of Beatty as the opening shots were fired.

Admiral Evan-Thomas’s four battleships of the Fifth Battle Squadron continued steaming north until 2.40pm due to a delay in receiving Beatty’s order to turn to the south south-east. The battle cruisers were increasing speed so the four battleships found themselves ten miles behind the rest of Beatty’s ships. This distance was to have an important impact.

Galatea, seeing a cloud of black smoke on the horizon indicating a substantial German presence, assumed this to be the German Battle Cruiser Fleet alone. This was in the light of the Admiralty’s information that Scheer and therefore the High Seas Fleet were still in harbour. Galatea and Phaeton turned north expecting the Germans to pursue them, thereby enabling Beatty’s battle cruisers to cut them off from their bases.

Jellicoe picked up Galatea’s messages and ordered the Grand Fleet to be ready for steam for full speed. He also assumed the German force was Hipper’s Battle Cruiser Fleet alone.

Rutland of Jutland:

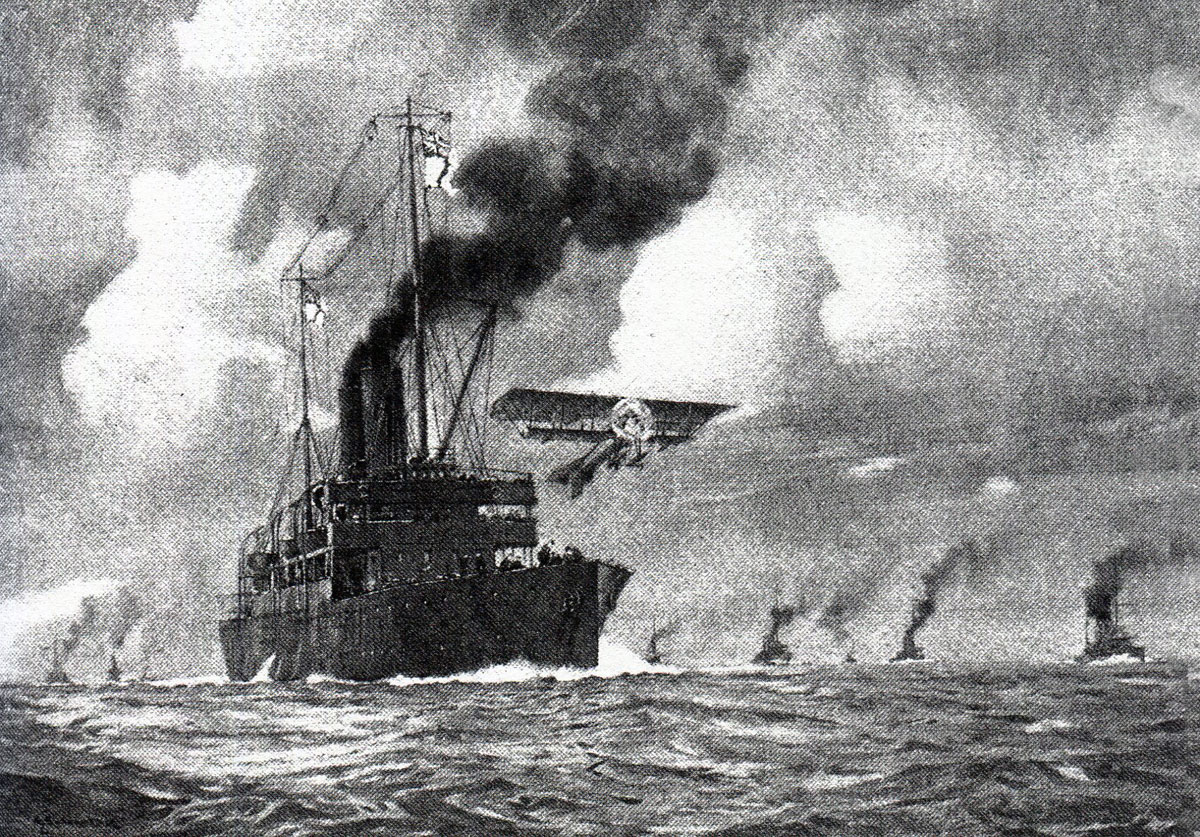

At 2.40pm Beatty signalled HMS Engadine to send up a seaplane to identify the German ships and establish their course.

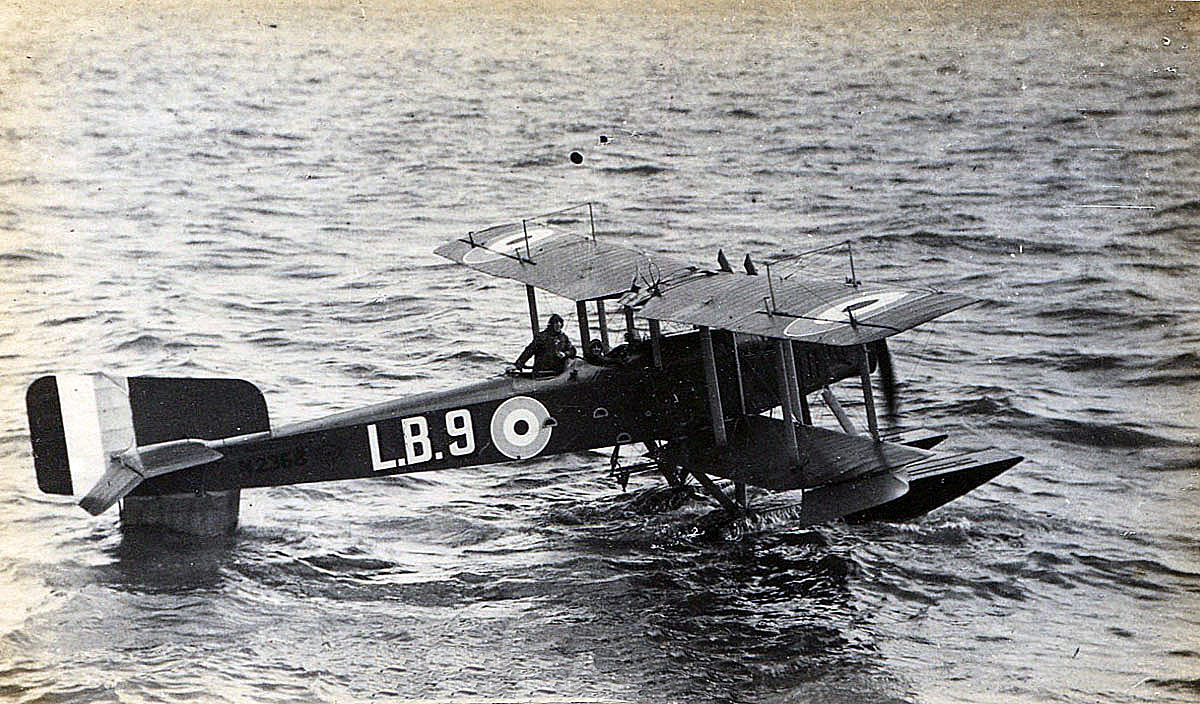

Short 184 Seaplane about to take off: as flown by Flight Lieutenant Frederick Rutland from HMS Engadine in the opening phase of the Battle of Jutland on 31st May 1916 in the First World War

At 3.08pm Flight Lieutenant Frederick Rutland with his observer Assistant Paymaster Trewin took off from Engadine in a Short 184 Seaplane.

British Seaplane Carrier HMS Engadine. Engadine fought at the Battle of Jutland on 31st May 1916 with Admiral Beatty’s Battle Cruiser Fleet. The seaplane that provided information on the approaching German ships was a Short 184 flown by Flight Lieutenant Frederick Rutland from Engadine

Rutland flew north north-east for ten minutes before sighting the German ships. Cloud cover was at around 1,100 feet with patches down to 900 feet causing Rutland to fly low.

Rutland was forced to fly within a mile and a half of the German ships to make out what they were and what they were doing. At this range the German light cruisers opened fire with every gun that would bear.

Rutland described the German shooting as ‘fairly good with shells exploding on my wing, before and behind me.

British Light Cruiser HMS Champion and 13th Destroyer Flotilla ahead of the Battle Cruisers at the beginning of the Battle of Jutland 31st May 1916: picture by Lionel Wyllie

The reporting of the plane’s observations was a slow business. The observer had to write his report down, encode it and then send it over his wireless by Morse code.

While Rutland was flying over the German ships they performed a 16 point turn (180 degrees), a manoeuvre that then had to be reported to Engadine by wireless in the same way.

Towards the end of the transmission the Germans began to jam Rutland’s wireless.

Flight Lieutenant Rutland takes off from HMS Engadine at the beginning of the Battle of Jutland 31st May 1916 in the First World War

Rutland kept on the bow of the German ships observing them. He then saw the British battle cruisers approaching which told him that his messages had got through.

At 3.45pm one of the aeroplane’s fuel leads broke forcing Rutland to land in the sea. He repaired the lead and was about to take off again to resume his observations when Engadine came up and hoisted him aboard.

Rutland received the Distinguished Service Cross for his conduct.

At 2.43pm Galatea reported seeing a substantial amount of smoke bearing east north-east indicating the presence of more German ships. Jellicoe ordered the Grand Fleet to cease zig zagging and proceed at 17 knots increasing to 18 knots.

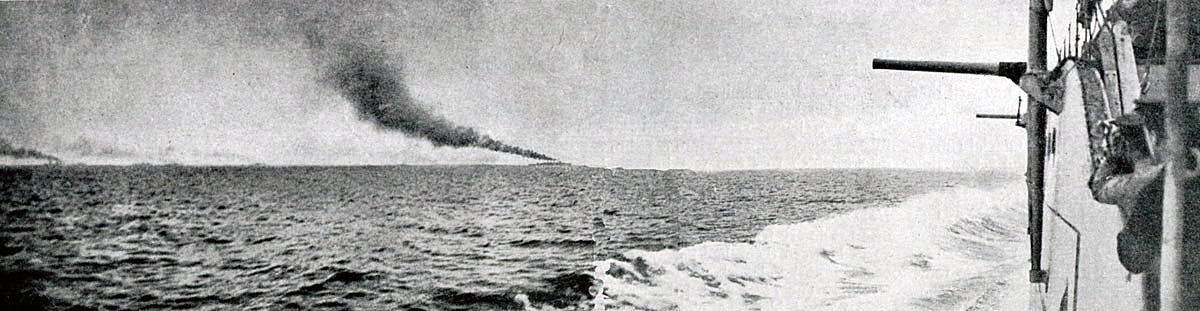

British battle cruisers first catch sight of the German ships at 3.20pm on 31st May 1916: contemporary photograph taken from a British ship

At around 3.20pm the opposing forces of battle cruisers caught sight of each other, the Germans seeing the British a few minutes in advance due to tricks of visibility in this notoriously difficult area of sea.

Commencement of the Battle of Jutland on 31st May 1916. British battle cruisers are in the distance behind the smoke line: contemporary photograph taken from the light cruiser HMS Champion

The German Battle Cruisers were heading north of north-west while Beatty’s ships were heading east of north-east. The German plan was for Hipper to turn back towards the High Seas Fleet, thereby luring the British Battle Cruisers onto Scheer’s battleship guns.

British Flotilla Leader HMS Fearless. Fearless led the 1st Destroyer Flotilla at the Battle of Jutland on 31st May 1916

Map of the ‘Run to the South’ by the British and German Battle Cruiser Fleets in the opening phase of the Battle of Jutland 31st May 1916: map by John Fawkes

Hipper turned with his five battle cruisers and accompanying light cruisers and destroyers onto a course heading south south-east while Beatty increased his speed to 25 knots and ordered New Zealand and Indefatigable to form line behind him.

First of a sequence of photographs of the opening stages of the Battle Cruiser action at the Battle of Jutland 31st May 1916 taken by Paymaster Lieutenant Duckworth from HMS Birmingham at 3.28pm. HMS Birmingham is shown on the right, HMS Nottingham in the left centre and the British Battle Cruisers on the left horizon

Beatty signalled Evan-Thomas to head east with 5th Battle Squadron at a speed of 25 knots. 9th and 13th Destroyer Flotillas led by HMS Fearless and Champion were ordered to form a screen in advance and to the starboard flank of the speeding battle cruisers.

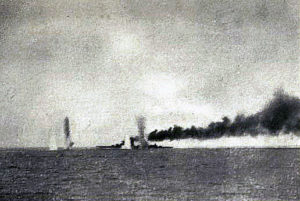

Second of a sequence of photographs of the opening stages of the Battle Cruiser action at the Battle of Jutland 31st May 1916 taken at 3.30pm by Paymaster Lieutenant Duckworth from HMS Birmingham. The vertical white clouds are spouts of water put up by exploding heavy calibre shells

When Beatty saw the German battle cruisers (Lützow, Derfflinger, Seydlitz, Moltke and von der Tann) they were hull down eleven miles away on the horizon. Rutland in his seaplane now reported that the German ships were heading south (the 12 point turn).

Third of a sequence of photographs of the opening stages of the Battle Cruiser action at the Battle of Jutland 31st May 1916 taken by Paymaster Lieutenant Duckworth from HMS Birmingham. The vertical white clouds are spouts of water put up by exploding heavy calibre shells

Beatty signalled his ships to form on a line north-west on a course east south-east in order to clear the smoke and enable them to open fire.

Fourth of a sequence of photographs of the opening stages of the Battle Cruiser action at the Battle of Jutland 31st May 1916 taken by Paymaster Lieutenant Duckworth from HMS Birmingham. The vertical white clouds are spouts of water put up by exploding heavy calibre shells

At 3.46pm Beatty signalled by flag the targets for each of his Battle Cruisers. This signal was not recorded by Tiger or New Zealand and Queen Mary appears also to have missed the signal (the destruction of Queen Mary prevented this being verified). In the signal Beatty took advantage of having six battle cruisers to Hipper’s five, ordering Princess Royal to fire with Lion on Hipper’s flagship Lützow, while Queen Mary fired on Derfflinger the second in the German line instead of the German third in line Seydlitz. Tiger was to fire on the German number three Seydlitz, New Zealand on the number four Moltke and Indefatigable to fire on the number five von der Tann. Not seeing the signal Queen Mary fired on her opposite number Seydlitz in accordance with Grand Fleet standing orders and Tiger and New Zealand both fired on Moltke. This left Derfflinger, the most powerful German battle cruiser, free from fire for some ten minutes until the error was realised on the British ships. This was a repeat of the error made at Dogger Bank where Derfflinger had been left free from fire by a similar misunderstanding.

Fifth of a sequence of photographs of the opening stages of the Battle Cruiser action at the Battle of Jutland 31st May 1916 taken at 4pm by Paymaster Lieutenant Duckworth from HMS Birmingham. The vertical white clouds are spouts of water put up by exploding heavy calibre shells

Both Battle Cruiser fleets opened fire at about 3.50pm at a range of 9 miles.

:

First of a series of photographs taken from a British destroyer at the Battle of Jutland on 31st May 1916 showing salvos of German shells landing short of HMS Lion

Second of a series of photographs taken from a British destroyer at the Battle of Jutland on 31st May 1916 showing salvos of German shells landing short of HMS Lion

Third of a series of photographs taken from a British destroyer at the Battle of Jutland on 31st May 1916 showing salvos of German shells landing short of HMS Lion

The German Battle Cruisers had the advantage that the British ships were outlined against the setting sun in the west, quickly picked up the range and began scoring hits. Additionally the German fire was evenly distributed along the British line. Lion and Tiger were quickly hit twice in the hull.

Beatty executed a number of small turns that brought the German ships closer. Soon the opposing Battle Cruiser squadrons were sailing on parallel courses south south-east at a range of 13,000 yards (7 ¼ miles) and engaging each other with main and secondary armaments.

The fire was too hot to endure for long and within minutes Hipper turned away to south east in line ahead and Beatty turned away to the starboard by two points. The range widened with the firing continuing.

The British firing was not effective, scoring few hits on the German ships. This may be explained by the presence on the engaged side of the British Battle Cruisers of a division of 9th Destroyer Flotilla comprising ‘L’ class destroyers from the Harwich Force. These destroyers were posted to the front of the Battle Cruisers but were older slower vessels than the run of destroyers in the Grand Fleet. In their strivings to maintain station in the fast moving battle the destroyers gave off substantial clouds of black smoke that masked Princess Royal and Tiger severely hampering their fire direction.

At around 3.58pm as Beatty turned away he signalled to increase the rate of fire. A salvo hit Derfflinger. Accurate German salvos of both main and secondary armament were coming in every twenty seconds. The ships were surrounded by water spouts as each salvo landed.

It is apparent from accounts that the effect of a salvo landing alongside a ship was significant: a terrifying explosion followed by mountains of dirty evil-smelling water deluging the ship accompanied by metal shrapnel.

Beatty signalled 13th Destroyer Flotilla to deliver a torpedo attack on the German Battle Cruisers.

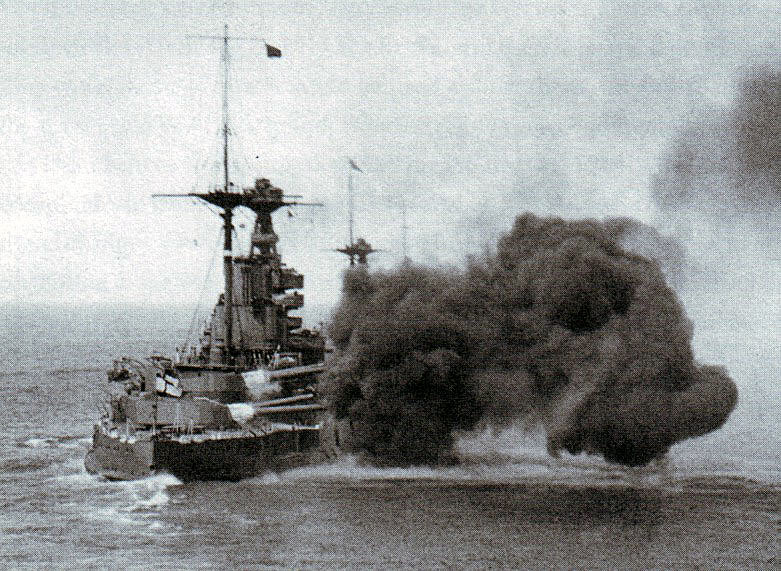

Admiral Beatty’s flagship HMS Lion struck on Q Turret during the Battle of Jutland on 31st May 1916: contemporary photograph taken from a British destroyer

Major Harvey RMLI awarded a posthumous Victoria Cross for his conduct on board HMS Lion at the Battle of Jutland on 31st May 1916

Lion hit on Q Turret:

At around 4pm a heavy shell probably from Lützow struck Lion’s Q turret. This strike was nearly the end of Lion. The shell penetrated the turret roof before exploding, killing almost all the gun crew in the turret. There was a severe danger that the fire that broke out in the turret would flash down into the magazine area beneath and cause the ship to blow up. The turret commander Major Harvey of the Royal Marine Light Infantry having lost both legs dragged himself to the voice tube connected to the control area beneath the turret and ordered the flash doors to be closed and the magazine flooded. This action probably prevented a catastrophic explosion although it caused the death by drowning of the magazine teams. Harvey received a posthumous Victoria Cross.

Flames shooting out of HMS Lion’s Q Turret after being hit by German shells: contemporary photograph taken from a British destroyer

From the beginning of the action Derfflinger fired on Princess Royal without being herself fired on. After some minutes Queen Mary realised the error and shifted her fire from Seydlitz to Derfflinger.

British Battle Cruiser HMS Indefatigable at about 3pm on 31st May 1916 half an hour before she was sunk. Indefatigable was lost at the Battle of Jutland when she was repeatedly struck by German salvos and exploded. Her entire crew was lost

Loss of HMS Indefatigable:

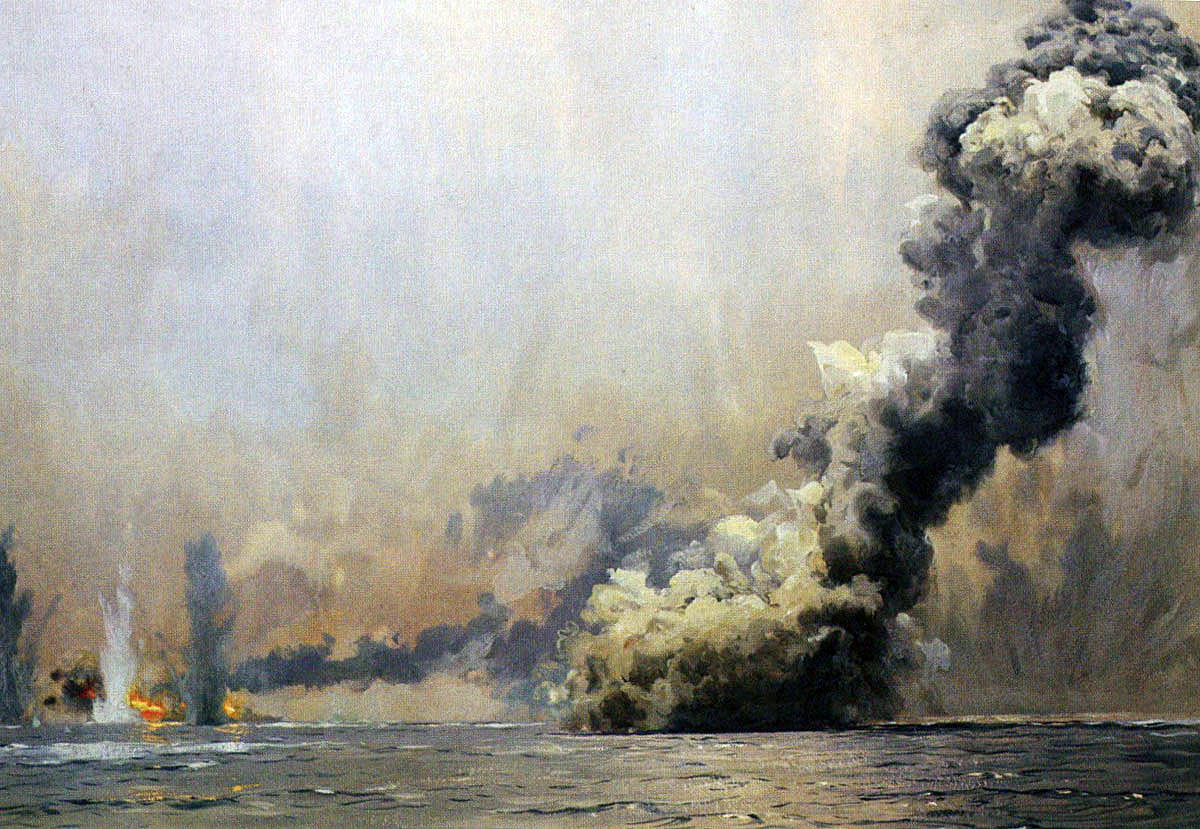

At the end of the opposing lines Indefatigable and von der Tann were firing on each other with increasing intensity. Just after 4pm a salvo of three shells struck HMS Indefatigable on her upper deck, concealing her in a column of smoke and flame. One or more shots must have penetrated to a magazine. Indefatigable fell out of the line sinking by the stern. Another salvo struck her and Indefatigable exploded. She turned over and disappeared. All 57 officers and 960 seamen of the crew of Indefatigable were lost.

The firing had now become so intense that Lion inclined away to starboard. The distance between the lines quickly widened until at 4.5pm the range was too great for the German guns and they ceased firing.

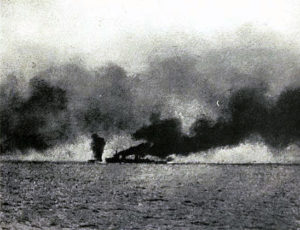

British Battle Cruiser HMS Indefatigable exploding after being repeatedly hit by shellfire at the Battle of Jutland on 31st May 1916. Photograph taken during the battle

5th Battle Squadron:

5th Battle Squadron (Barham, Valiant, Malaya and Warspite) was eight miles behind the German battle cruisers. Evan-Thomas’s battleships fired salvos at the German light cruisers in the rear of Hipper’s fleet forcing them away eastwards.

British 5th Battle Squadron Vice-Admiral Evan-Thomas’s Flagship HMS Barham HMS Valiant HMS Malaya and HMS Warspite all Queen Elizabeth Class Battleships

At 4.5pm Evan-Thomas came in sight of both Beatty’s ships and the rearmost German ship von der Tann. Evan-Thomas followed Beatty in his inclination towards the south and Barham opened fire on von der Tann. Although the range was 19,000 yards (just under eleven miles) Barham’s salvos straddled the von der Tann which began to zig-zag to avoid being hit.

5th Battle Squadron; HMS Valiant, Warspite & Malaya about to open fire; taken from HMS Barham. 5th Battle Squadron fought at the Battle of Jutland on 31st May 1916 as part of Admiral Beatty’s Battle Cruiser Fleet

However Von der Tann was hit and it seems that only the poor quality of the British shells (a problem encountered by the British Army in the following months during the Somme Offensives) prevented the von der Tann from being sunk.

Soon the battle cruisers largely disappeared from the view of Evans-Thomas’s battleships due to the distance and the haze. Evan-Thomas managed to continue firing at the German gun flashes at extreme range as the opposing battle cruiser forces inclined towards each other.

British Battle Cruiser HMS Queen Mary. Queen Mary blew up and sank in the opening part of the Battle of Jutland on 31st May 1916

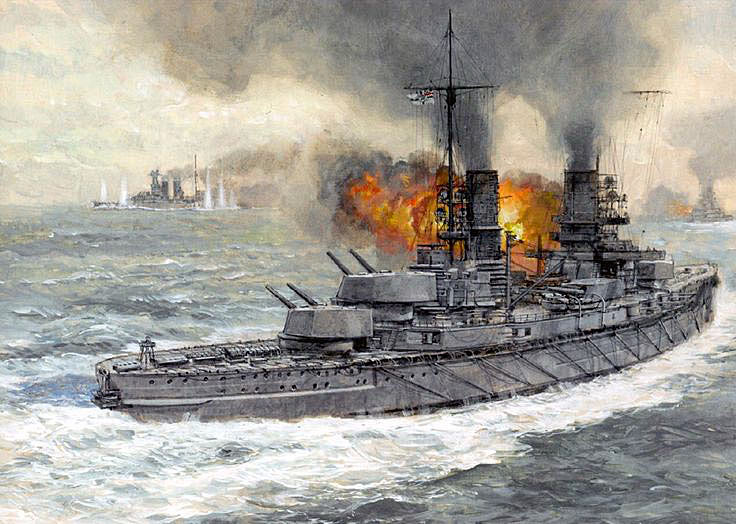

British battle cruiser HMS Queen Mary explodes after being repeatedly struck by shells from German battle cruisers SMS Derfflinger and Seydlitz, Battle of Jutland 31st May 1916: comtemporary photograph taken from HMS Lydiard

Loss of HMS Queen Mary:

Fires on board Lion obscured her from view causing Derfflinger to take the Princess Royal as the leading British ship instead of Lion. Derfflinger therefore fired on the next ship in line HMS Queen Mary. Queen Mary was also being fired on by Seydlitz.

At 4.26pm Queen Mary was struck by a salvo from Derfflinger on her forward deck. There was an explosion and Queen Mary immediately sank by the bows leaving her stern and still revolving propellers in the air as Tiger and New Zealand sped past on either side.

57 officers and 1,209 sailors on Queen Mary were lost. 18 survivors were picked up by British destroyers. 1 officer and 1 sailor were rescued by German destroyers.

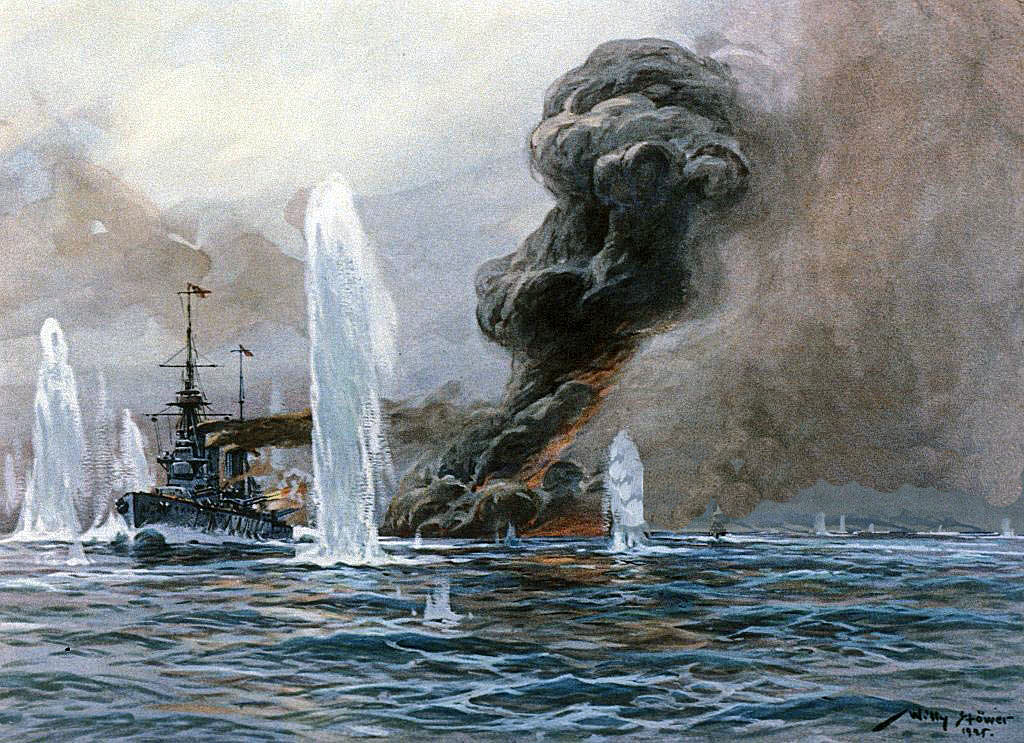

British battle cruiser HMS Queen Mary explodes at the Battle of Jutland on 31st May 1916: picture by Claus Bergen from the contemporary photograph taken by a British officer

In spite of the unexpected success in sinking two British battle cruisers Hipper was in increasing trouble. The battleships of Evan-Thomas’s 5th Battle Squadron were engaging his rear ships and ahead of Beatty’s battle cruisers the 13th Destroyer Flotilla was preparing for its attack on the German battle cruisers.

Chief Stokers on British Battle Cruiser HMS Queen Mary, all lost when Queen Mary blew up and sank during the Battle of Jutland on 31st May 1916

13th Destroyer Flotilla attack:

At 4.15pm Captain Farie of HMS Champion, the flotilla leader, gave the order to attack. Nestor (Commander Bingham) led Nomad, Nicator, Pelican and Narborough across Lion’s bows towards the German line, followed by Petard, Obdurate, Nerissa, Turbulent, Termagent (these two of 9th Flotilla), Moorsom and Morris (these two of 10th Flotilla).

German Battle Cruiser SMS Derfflinger firing a full salvo. Derfflinger fought at the Battle of Jutland on 31st May 1916 in Admiral Hipper’s 1st Scouting Group

As the British destroyers crossed the eight miles of sea to reach the German battle cruisers they passed German destroyers tasked to attack the British 5th Battle Squadron to relieve the increasing pressure on Hipper’s battle cruisers.

British destroyers of the 13th Flotilla begin their attack as HMS Queen Mary blows up at 4.26pm during the Battle of Jutland 31st May 1916

The British destroyers turned north and attacked the German destroyers. The German destroyers, smaller and less well armed than the British ships, fired their torpedoes and hurriedly withdrew.

The 5th Battle Squadron turned away two points and none of the torpedoes struck its ships.

British Destroyer HMS Nicator. Nicator fought with the 13th Destroyer Flotilla at the Battle of Jutland on 31st May 1916

Bingham’s destroyers now turned to attack the German battle cruisers. Nestor and Nicator fired a number of torpedoes at Hipper’s flagship SMS Lützow. The German ship took evasive action and none hit.

The remaining destroyers were involved in a confused melee with the German destroyers until 4.43pm when Lion recalled the British vessels. They withdrew leaving two German destroyers V27 and V29 sinking.

Nomad was also sinking and Bingham’s ship Nestor was left disabled by hits from SMS Regensburg the German flotilla light cruiser.

The German High Seas Fleet appears:

The reason for the recall was that the strategic situation had taken a surprising turn.

At 4.33pm Commodore Goodenough in HMS Southampton two miles ahead of Lion on the port bow signalled that battleships were in sight to the south-east. This was the main body of the German High Seas Fleet.

Within minutes Beatty was able to see the German battleships, confirmed by Champion in advance of the battle cruisers.

Beatty was taken by surprise. The information from the Admiralty in London had been that the German commander-in-chief Admiral Scheer’s call sign was still located in Kiel but here was the German High Seas Fleet sailing towards him with its overwhelming array of modern battleships.

Beatty immediately turned to port towards where the supposed German fleet was reported from and maintained his course until he was 13,000 yards (7.3 miles) from the approaching battle fleet and the Germans opened fire before signalling a complete reversal of his battle cruiser fleet’s course to north-west at 4.40pm and then to a northerly course to head for Jellicoe’s Grand Fleet.

British Battle Cruisers turning from south to north on sighting the German High Seas Fleet and beginning the ‘Run to the North’ Battle of Jutland 31st May 1916 Lion turning Princess Royal straddled: contemporary photograph taken from a British ship

As Beatty’s battle cruisers executed the change of course in turn they came under fire from the approaching German battleships, managing to avoid the fall of shot by zig-zagging.

The German 3rd Squadron commanded by Rear-Admiral Behncke in SMS König led the German High Seas Fleet with seven ‘König’ and ‘Kaiser’ battleships, followed by five ‘Helgolands’ and four ‘Nassaus’. In the rear were the six pre-Dreadnoughts of the 2nd Squadron.

Admiral Scheer the German commander-in-chief had his flag in SMS Freidrich Der Grosse the eighth ship in the line.

Accompanying the battleships were five cruisers of 4th Scouting Group and three and a half flotillas of destroyers (torpedo boats) led by the light cruiser Rostock.

German Battleships open fire in the early stages of the Battle of Jutland 31st May 1916: picture by Claus Bergen

Scheer continued on his course to the north until 4.5pm when he turned to the north-west. At 4.20pm Scheer turned his line to the west to put Beatty’s battle cruisers between the fires of his battleships’ and the battle cruisers’ of Hipper’s 1st Scouting Group.

Almost immediately Scheer heard that Hipper was under heavy fire from Evan-Thomas’s newly arriving 5th Battle Squadron and turned north again to save Hipper from the very same trap Scheer had intended for Beatty.

The German battleships advanced into the area across which the British destroyers of the 13th Flotilla were withdrawing. Nestor and Nomad lay immobilised and were quickly destroyed by German gunfire, their crews rescued by a German destroyer. Nicator and Petard renewed their torpedo attack on Hipper’s battle cruisers. Petard fired three torpedoes one of which hit Seydlitz on the starboard side under her armour belt blowing a 39 X 13 foot hole and immobilising a gun. Seydlitz continued in action.

In all the British destroyers fired twenty torpedoes and caused the German battle cruisers to veer away from Beatty’s ships. Each side lost two destroyers.

German High Seas Fleet leaving for the North Sea on 30th May 1916 for the Battle of Jutland: picture by Claus Bergen

The Race to the north:

At 4.49pm Hipper resumed his southerly course after his turn away as Beatty’s battle cruisers headed north after their 16 point turn to the north-west followed by the turn north. The two battle cruiser squadrons resumed firing, Lion engaging von der Tann the nearest of the German ships at extreme range.

Hipper then executed a 16 point turn to the starboard to take up position in advance of Scheer’s High Seas Fleet (the conventional position of each nation’s battle cruisers in a fleet action was in advance of the battleship line).

The misty conditions caused the two sides to lose sight of each other and firing ceased.

German Battleships and Destroyers advancing to the attack at the Battle of Jutland on 31st May 1916: picture by Claus Bergen

At around 5pm the ships of each side were able to see each other again and firing resumed. Lion received a hit which caused a near catastrophic fire.

Positioned to the west of the German ships the British battle cruisers were outlined against the setting sun while the German ships were shrouded in mist and difficult to see with sufficient precision for accurate shooting.

At around 5.8pm the two sides were again out of range. Beatty reduced speed to 24 knots and continued north to meet Jellicoe’s advancing battle fleet.

Evan-Thomas’s 5th Battle Squadron had begun the turn to the north some minutes after Beatty, not immediately seeing the German High Seas Fleet and taking a little time to react to the order for the 16 point turn.

British Battleship HMS Barham Admiral Evan-Thomas’s Flagship in 5th Battle Squadron at the Battle of Jutland 31st May 1916

Evan-Thomas’s ships turned in succession so that each succeeding ship was nearer the German battleship line and to Hipper’s ships than her predecessor in the line. The leader HMS Barham was heavily hit. Valiant turned unscathed, Warspite was hit several times and then Malaya received the fire of the whole of the leading squadron of German battleships.

Malaya was struck several times and began to list. For around half an hour Malaya was the target for much of the German fleet.

The 5th Battle Squadron continued on a northerly course, the leading ships Barham and Valiant firing on Hipper’s battle cruisers while Warspite and Malaya fired on Scheer’s battleships. As Scheer was on a north westerly course the range kept reducing in spite of the greater speed of the four ‘Queen Elizabeths’ of Evan-Thomas’s squadron.

German Battleship SMS Kaiser fires on HMS Warspite before 5th Battle Squadron turns to the north during the opening phase of the Battle of Jutland on 31st May 1916

Two British destroyers of 13th Flotilla, HMS Onslow and Moresby, appeared returning from escorting the seaplane carrier HMS Engadine. Seeing that the German battleships had no preceding destroyer or light cruiser screen Onslow and Moresby resolved to carry out a torpedo attack. As they did so four light cruisers of Hipper’s screen appeared and opened fire on them. Onslow sheared off but Moresby continued with her attack closing to within 8,000 yards (4 ½ miles) of the third German battleship SMS Markgraf and firing a torpedo which missed its target.

At around 5.20pm Evan-Thomas turned to north north-west into the wake of Beatty’s battle cruisers, the range opened up and by around 5.30pm the distance and the misty gloom was such that the German ships could only be glimpsed. The running fire fell away although hits were still occasionally achieved.

Scheer ordered his ships to pursue the escaping British ships with all the speed that could be achieved unaware that he was hastening towards Jellicoe’s battleships (Jellicoe commanded twenty-four Dreadnought battleships and seven battle cruisers against Scheer’s sixteen Dreadnought battleships six pre-Dreadnought battleships and five battle cruisers, a severe mismatch).

The previous battle of the First World War is the Battle of Jutland Part I

The next battle of the First World War is the Battle of Jutland Part III