The iconic action fought on 1st September 1914 in the First World War: the British 1st Cavalry Brigade repelled a surprise attack by the German 4th Cavalry Division, capturing 12 German guns, with 3 Victoria Crosses awarded to ‘L’ Battery, Royal Horse Artillery

The previous battle in the First World War is the Battle of Heligoland Bight

The next battle in the First World War is the Battle of Villers Cottérêts

Battle: Néry

Date of the Battle of Néry: 1st September 1914.

Place of the Battle of Néry: North East France.

War: The First World War also known as ‘The Great War’.

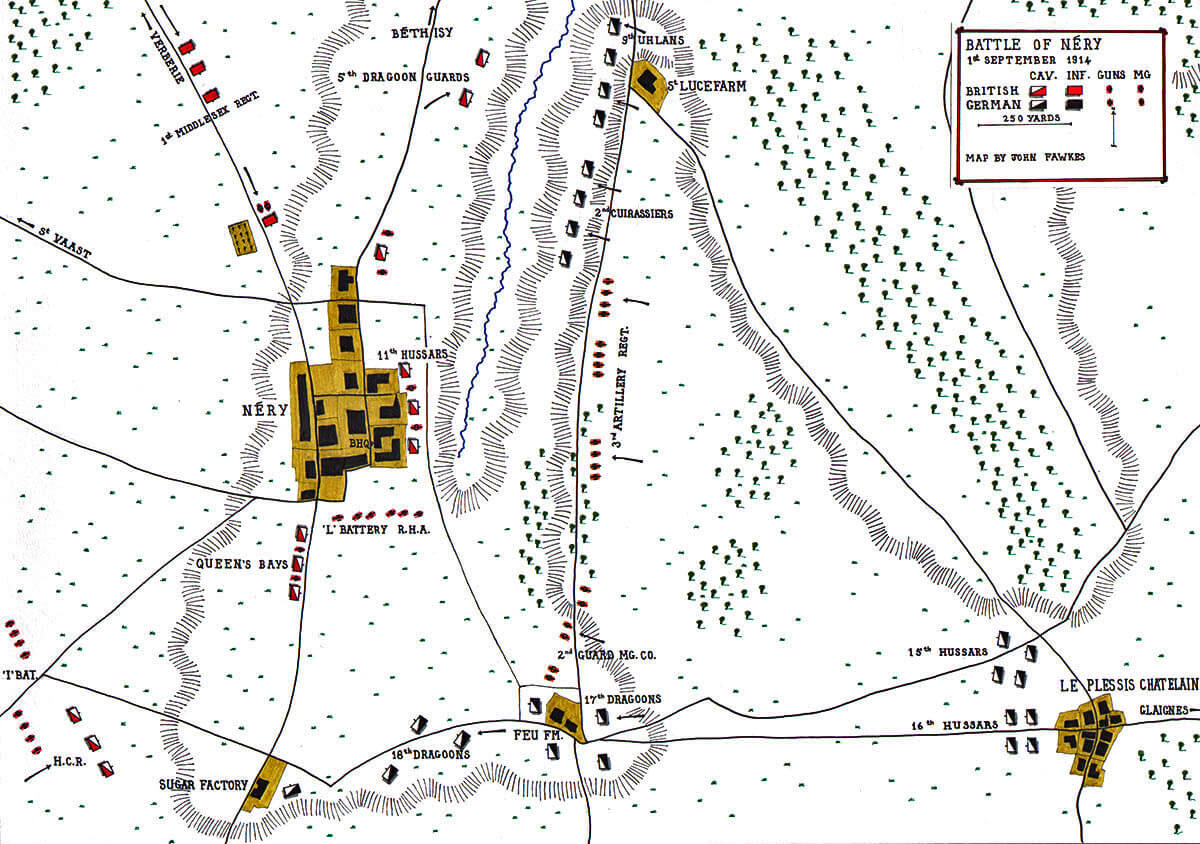

Contestants at the Battle of Néry: The British Expeditionary Force: 1st Cavalry Brigade, comprising 2nd Dragoon Guards (Queen’s Bays), 5th Dragoon Guards, 11th Hussars and L Battery, Royal Horse Artillery; later assisted by units from 4th Cavalry Brigade, I Battery, Royal Horse Artillery and the Household Cavalry Regiment, and by the 1st Middlesex Regiment of 19th Brigade.

German 4th Cavalry Division, comprising 2nd Cuirassiers, 9th Uhlans, 15th and 16th Hussars and 17th and 18th Dragoons, 3rd Artillery Regiment and 2nd Guard Machine Gun company.

Commanders at the Battle of Néry: Brigadier-General C.J. Briggs commanded the British 1st Cavalry Brigade. Major-General von Garnier commanded the German 4th Cavalry Division.

Size of the Armies at the Battle of Néry: 1st Cavalry Brigade comprised around 1,500 men and the same number of horses, 6 guns and 6 machine guns. The German 4th Cavalry Division comprised around 5,000 men and the same number of horses, 12 guns and 6 machine guns.

1st Middlesex Regiment comprised around 800 men with 2 machine guns.

I Battery, RHA, comprised 8 guns (its own 6 and 2 others from a reduced battery).

Winner of the Battle of Néry: The British 1st Cavalry Brigade.

Uniforms and equipment at the Battle of Néry: See this section in the Battle of Mons here.

Background to the Battle of Néry: See this section in the Battle of Mons here.

Account of the Battle of Néry: As the BEF, with the French Fifth Army under General Lanrezac on its right, retreated before the German First and Second Armies (General von Kluck and General von Bülow), Kluck ceased his advance to the south west and swung his First Army round to the south east.

Following the battle of Guise on 29th August 1914, after which the French Fifth Army of General Lanrezac pulled back towards the south east, the German High Command considered the French to have been defeated at the western end of the line and the BEF to be in a state of rout and no longer to be a viable fighting entity.

This change of direction by von Kluck would, in due course, give General Joffre his opportunity to launch the French 6th Army, under General Manoury, with the Paris garrison, under General Gallieni, from the west against von Kluck’s open right flank.

In the meantime, the BEF and the French armies continued to retreat towards the Marne River.

On 31st August 1914, the BEF alignment was that I Corps lay to the south west of Soissons, II Corps lay to its west and the newly formed III Corps, comprising 4th Division and 19th Brigade, was positioned along the Oise River at Verberie. The brigades of the Cavalry Division were dispersed along the line.

There was a gap of around 5 miles between II and III Corps. In that gap, on the night of 31st August/1st September 1914, the 1st Cavalry Brigade encamped in the village of Néry. The retreat was to be resumed at first light on 1st September.

The 3 cavalry regiments of the 1st Cavalry Brigade arrived at Néry during the evening of 31st August. L Battery, RHA, halted in the village of Verberie to water its horses, in the expectation that a small village like Néry would be hard pressed to provide watering facilities for the 1,500 horses of the whole brigade, and reached Néry at around 10pm.

Néry comprised a rough rectangle of mainly farm buildings, with the church at the north-east corner. A sugar factory, for processing the locally grown sugar beet, lay about ¼ mile to the south of the village. A farm, Feu Farm, lay on the road out of Néry to the east which led to the neighbouring village of Le Plessis Chatelain.

The 3 cavalry regiments were distributed around Néry, with the 11th Hussars in large stone farm buildings on the east side, just south of the church, the Queen’s Bays in a field and buildings at the south west corner of the village, and the 5th Dragoon Guards in a field on the northern side of the village.

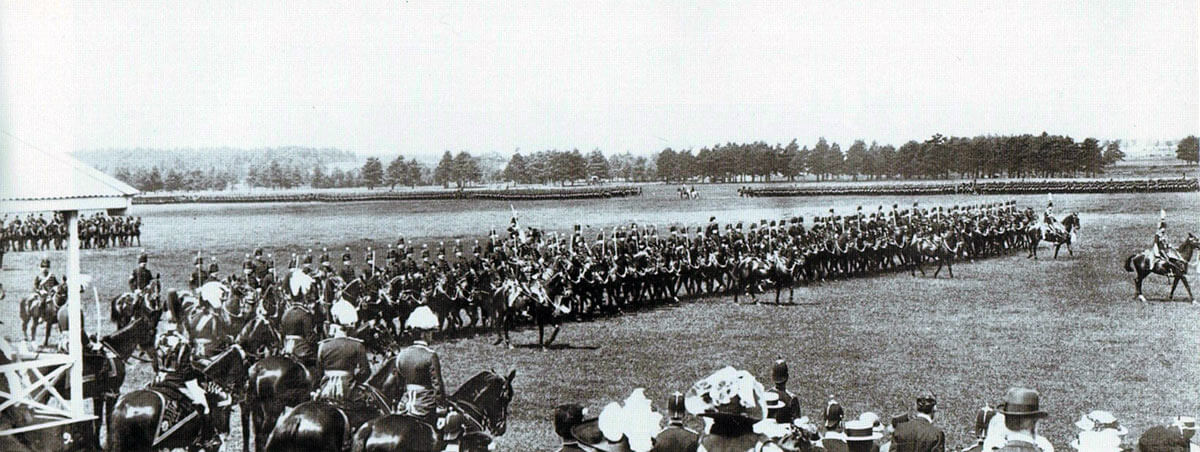

German dragoon regiment during peace time manoeuvres: Battle of Néry on 1st September 1914 in the First World War

Brigade headquarters was situated in a farm building at the south-east corner of the village.

L Battery, as the last arrivals, occupied a field on the south-east corner of Néry and had the use of neighbouring buildings.

Running up the east side of Néry is a small stream, flowing north into the Automne River, which joins the Oise just north of Verberie. The stream occupies a 20 metre deep ravine. This ravine was a dominant feature in the battle. The ravine was not easily seen and was a substantial barrier to troops approaching the village from the high ground to the east. Access to Néry from the east was by way of the road from Le Plessis Chatelain, passing the southern end of the ravine. The eastern, German, side of the ravine was 20 metres higher than the western side, giving the eastern side a good overview of the village of Néry, in the absence of fog. The position and depth of the ravine made it an essential component in the battle.

Another important feature of the battle was the fog that clothed the area from early on 1st September until around mid-morning.

1st Cavalry Brigade was due to march out of Néry at 4am to continue the retreat to the south-west. For L Battery this required reveille to be at 2.30am for the gunners to prepare the horses, guns and transport for the day’s march.

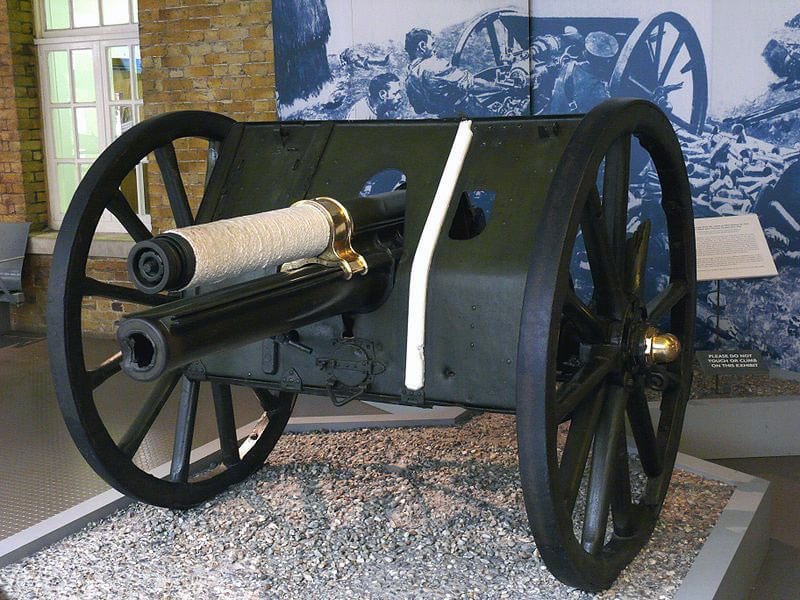

Royal Horse Artillery 13 pounder Quick Firing gun: Battle of Néry on 1st September 1914 in the First World War

The timings of the battle vary from account to account, but it would seem that with first light, around 4am, it was clear that the poor visibility, due to the fog, precluded an early start and the British regiments were stood down for the time being. The 11th Hussars ‘off-saddled’, and the other regiments probably did the same. The practice in the Royal Horse Artillery was to leave the horse teams in harness but to ‘drop poles’ (the towing bar), so that the horses were relieved of the weight of the poles, but remained harnessed in teams. The horse artillery teams were then watered in turn to take advantage of the delay.

At around 5.30am, German shells started bursting over Néry.

A number of factors seem to explain the complete surprise of 1st Cavalry Brigade by the Germans.

Brigadier-General Briggs, the commander of the brigade, appears to have been unaware that there were no other British units to his north-east between his brigade and any approach route for the pursuing Germans. As the brigade was only intending to spend a few hours in Néry, perhaps it was considered unnecessary to put outposts in the neighbouring villages. It would appear that this course was considered and rejected, as it would not have been easy to have supported such outposts, due to the topography; presumably the existence of the ravine.

View of Néry from German gun positions: Battle of Néry on 1st September 1914 in the First World War (The ravine is out of sight at the end of the field to the front)

It was Briggs’ practice to leave local security to individual regiments.

The only precaution taken seems to have been by the 11th Hussars, which sent out an ‘officer’s patrol’ at around 4.15am under 2nd Lieutenant Tailby. Tailby’s patrol comprised a corporal and 5 troopers. This patrol set out to the east of Néry crossing the ravine, with some difficulty, up to the plateau to the east of the village. The patrol circled the plateau, and was about to return to Néry, when it saw numbers of German soldiers in the fog, both mounted and dismounted. The Germans seemed to be unsure of their position. 1 of the 11th Hussars fired on the Germans, who pursued the patrol. Tailby was forced to take his men at the gallop to the north. Tailby’s horse tripped, throwing the officer. Despite this the patrol got away from the pursuing Germans.

Tailby’s patrol rode into the outskirts of Bethisy-St Pierre, to the north of Néry. They there surprised 3 German troopers at an estaminet, who rode off leaving a cloak and a rifle. Tailby took the cloak with him. The patrol turned onto the road to Néry, near the railway line, and rode back to the village, coming into Néry from the north. Tailby sent his corporal to warn the 5th Dragoon Guards of the presence of German cavalry to the east of the village, while he rode on to report to the commanding officer of the 11th Hussars, Lieutenant Colonel Pitman. Tailby produced the German cloak to his colonel, to support his report. The time was around 5.30am and the German bombardment began almost immediately.

The German II Cavalry Corps of General von der Marwitz, comprising the 2nd, 4th and 9th Cavalry Divisions, was advancing on the eastern flank of General von Kluck’s First Army. On the night of 31st August 1914, Marwitz’s cavalry was moving south east in a line from the west of the Oise River through the forest of Compiegne. General Garnier’s 4th Cavalry Division crossed the Automne River and moved south, several miles to the east of Néry.

Garnier was aware that ahead of him, in a westerly direction, lay the village of Néry, occupied by British troops. He resolved to launch an assault on Néry, with his 3rd Cavalry Brigade on the right and his 17th Cavalry Brigade on the left. The 12 guns of 3rd Artillery Regiment were to be deployed at the western end of the plateau, with the Guard Machine Gun Company on the left of the gun-line. The divisional headquarters remained in the village of Le Plessis Chatelain, 1 ½ miles east of Néry, with Garnier’s remaining 18th Cavalry Brigade, comprising the 2 hussar regiments, the divisional field ambulance and other divisional units.

The Germans were also hampered by the fog. It was apparent that the German troops Tailby encountered, during his patrol, were uncertain as to where they were.

An important consequence of the fog was to prevent the Germans from seeing the ravine, lying between the plateau and the village of Néry, until the 4th Division cavalry units attempted to launch their attack towards Néry. On both wings the German regiments were compelled to dismount and feel their way around the ravine, on the left to Feu Farm and then on to the Sugar Factory. On the right the 9th Uhlans and 2nd Cuirassiers of the German 3rd Cavalry Brigade, after dismounting, began to move forward on foot.

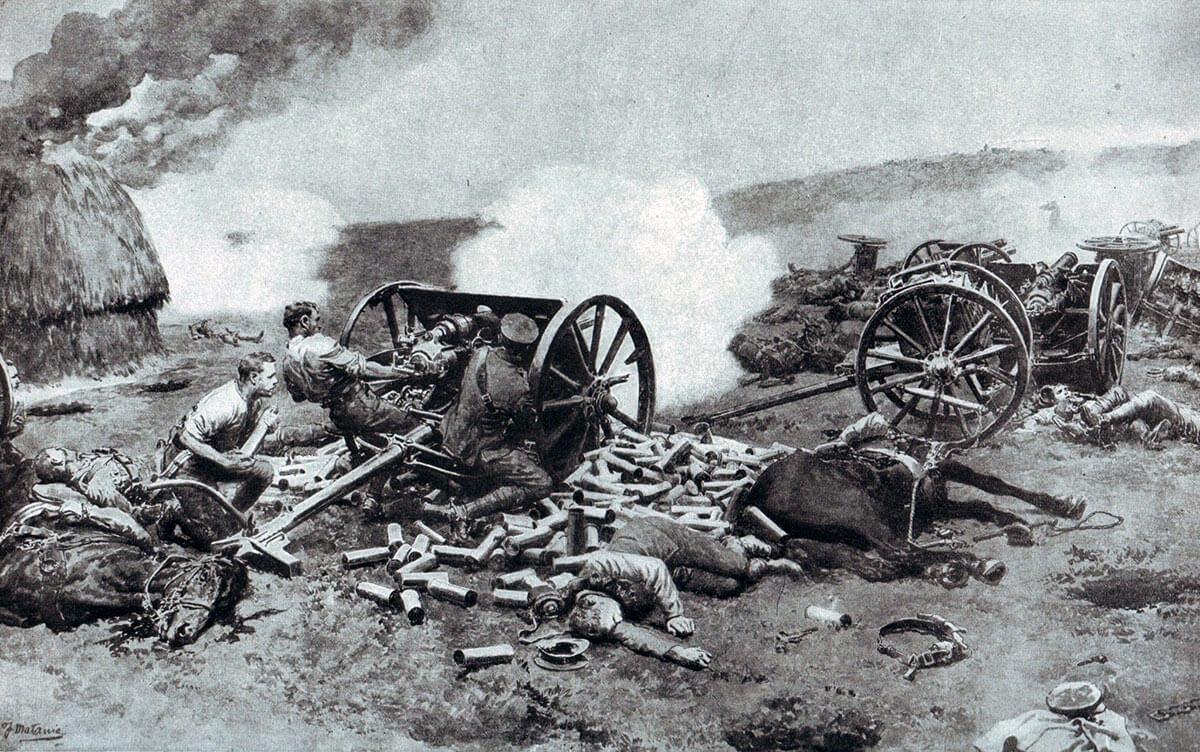

L Battery in action at the Battle of Néry on 1st September 1914 in the First World War: from a sketch drawn by BSM Dorrell after the battle

Equally damaging, the fog caused the German artillery regiment to establish its gun line too close to Néry for the gunners to be safe from British rifle and machine gun fire, and without any intervening German troops.

The German bombardment of Néry began at around 5.30am as Tailby was reporting to his commanding officer, Lieutenant Colonel Pitman. L Battery was formed up in the field nearest to the German gun line, awaiting the time to move off, while its horses were watered in turn. The horses of the Queen’s Bays were in the field on the far side of the street running north to south from Néry village to the sugar factory. The 5th Dragoon Guards and their horses were in the field at the northern end of the village.

The 11th Hussars horses were inside the extensive farm buildings and enclosures that housed the regiment during the night.

Brigadier-General Briggs was at his headquarters in the farm building at the south-east corner of the village. The battery commander of L Battery, Major Sclater-Booth RHA, was with the brigade commander.

As the bombardment began, the brigade major, Major Crawley, rushed outside and was caught in the explosion of one of the first German shells. He died of his wounds later in the day.

German hussar regiment during peace time manoeuvres: Battle of Néry on 1st September 1914 in the First World War

L Battery, Royal Horse Artillery:

As the unexpected bombardment began, Major Sclater-Booth hurried off to re-join his battery, to be caught in a shell burst that left him unconscious.

L Battery, formed up ready to move off in the field nearest to the German gun-line, was devastated by the storm of German shell and machine gun fire. Most of the battery horses, standing in harness in the open field and unable to move due to the ‘dropped poles’ procedure (as soon as the teams moved, the ends of the poles buried themselves in the ground), were struck down by the shrapnel bursts overhead, along with a number of the gunners.

While initially many of the surviving gunners took cover among the haystacks on the northern side of the field, very quickly 4 of the battery’s 6 guns were brought into action, firing at the German batteries.

According to the sketch made by Battery Sergeant Major Dorrell after the battle, the L Battery guns were in a line east to west. There was no opportunity to move the guns. Each gun was simply extracted from the team of dead and dying horses, swung around to face east, and brought into action, even though this meant firing over the neighbouring gun.

The L Battery guns were all in turn put out of action by the German gun-fire, until only F gun, the gun nearest to the German batteries, was firing.

It would seem that the L Battery guns fired were B, C, D and F. A and E were damaged so as to be unusable by German high explosive shells. British RHA batteries were issued only with shrapnel shells and not with high explosive, while the Germans were firing both.

Probably the first L Battery gun into action was D Gun manned by Bombardier Perrett, whose gun it was, and Lieutenant Campbell. The initial range was 800 yards. Perrett saw that they were overshooting the German guns and reduced the range to 500 yards, with the shrapnel fuse at Zero, soon increased to 1 ½ seconds. Perrett saw their shells exploding over the German gun-line.

The Néry gun in the Imperial War Museum (C Gun): Battle of Néry on 1st September 1914 in the First World War

Other gunners came up. Lieutenant Campbell and Bombardier Perrett handed D Gun over to these men, to continue firing, and moved on to C Gun, bringing it into action. 2 other gunners joined them. They fired C Gun until the 2 gunners were killed and Perrett wounded. A German round struck the muzzle of the gun preventing it from being fired further.

B Gun was brought into action by Lieutenant Giffard, with Sergeant Phillips and Gunner Richardson, soon joined by other gunners. After firing about 8 rounds, a German shell killed several members of the gun crew. Giffard and Phillips continued firing, until another round blew off a wheel, turning the gun over, also killing Phillips and wounding Giffard. Giffard crawled to the haystacks, being wounded again on the way.

Lieutenant Mundy of L Battery Royal Horse Artillery killed at the Battle of Néry on 1st September 1914 in the First World War

Gunner Darbyshire and other gunners brought F Gun into action, but the gun was at the eastern end of the battery line and the other guns were firing over it. The explosions of each discharge concussed Darbyshire who found he was bleeding at the nose and ears. He was forced to hand over his position on the gun and fetch ammunition instead.

F Gun was crewed by Lieutenants Campbell and Mundy, Sergeant Nelson and Corporal Payne. At the end of the gun-line and nearest to the Germans, F Gun was hit by shrapnel shells several times and swept by German machine gun fire. Campbell was killed and Mundy and Payne fatally wounded. F Gun was taken over by Captain Bradbury, Battery Sergeant Major Dorrell and Sergeant Nelson, who was wounded but insisted on remaining with the gun. Darbyshire assisted by carrying ammunition from the limbers.

Bradbury went to collect more ammunition and was caught by an exploding shell, which took off both his legs. He died later that day.

Nelson and Dorrell continued firing F Gun, until around 8am when I Battery RHA, coming up with the relief provided by 4th Cavalry Brigade, began firing over the village into the German guns, which ceased firing at that time or soon afterwards.

The final gun of L Battery in action, F Gun: Battle of Néry on 1st September 1914 in the First World War: picture by Fortunino ‘Freddie’ Matania

1st Cavalry Brigade Headquarters:

After interviewing 2nd Lieutenant Tailby at 5.30am, Lieutenant Colonel Pitman hurried along the street to Brigade Headquarters, to report Tailby’s sighting of German cavalry on the plateau to the east of Néry. Almost immediately the German shells began to burst over the village.

Brigadier-General Briggs is said to have picked up a fuse from one of the exploded shells, seen the markings on the fuse written in German Gothic script, and confirmed that the gun-fire was from German batteries.

Brigadier-General Briggs, commanding 1st Cavalry Brigade, sitting on a bridge with his staff in October 1914: Battle of Néry on 1st September 1914 in the First World War

Briggs, at about 5.40am, sent motorcycle despatch riders to seek assistance from Major-General Allenby, the Cavalry Division commander at St Vaast, and from Major-General Snow, commanding 4th Division, in the area of Verberie to the north west of Néry.

For the immediate defence of Néry, Briggs ordered the 5th Dragoon Guards to counter-attack to the north east of the village, the 11th Hussars to defend the east side of the village, and the Queen’s Bays to assist L Battery and to secure the sugar factory and the south east of the village.

The 11th Hussars passing in review before King George V at Aldershot in June 1914: Battle of Néry on 1st September 1914 in the First World War

11th Hussars:

The 11th Hussars was the first regiment in 1st Cavalry Brigade to be ready for the battle, after Tailby’s warning and seeing the German cavalry cloak that he carried. The regiment’s horses were either under cover in the extensive stone farm buildings or concealed in walled gardens and courtyards. The troops found positions along the east side of the village, and opened rifle and machine gun fire on the Germans on the far side of the ravine, primarily the German gunners and the left wing of the German 3rd Cavalry Brigade. The 11th Hussars continued firing until the battle effectively ended, at around 9am.

Towards the end of the battle, and after the German guns ceased firing, C Squadron of the 11th Hussars was ordered to attack. They did so in co-operation with the 1st Middlesex Regiment, the first relieving infantry into Néry from 19th Brigade in the Verberie area. The German gun line was taken, and C Squadron moved on to Le Plessis Chatelain, where they captured the German divisional field ambulance with around 100 personnel and wounded soldiers from the German regiments.

After firing on the German gun-line, the 11th Hussars machine gun troop moved to the south-east corner of the village and joined the machine gunners and troopers of the Queen’s Bays in firing on the Germans in the Sugar Factory, until they were driven out or captured.

Lieutenant Colonel George Ansell commanding officer of 5th Dragoons Guards, killed at the Battle of Néry on 1st September 1914 in the First World War

5th Dragoon Guards:

The 5th Dragoon Guards were quartered in a field at the northern end of Néry. Corporal Parker, the NCO in Tailby’s patrol, veered off as the patrol galloped into Néry down the Bethisy Road at around 5.30am. Parker found the 5th Dragoon Guards sceptical of his warning that there was German cavalry on the plateau just to the east of the village. No one was prepared to accept that the Germans were that close. Almost immediately, this scepticism evaporated as the German bombardment of the village began.

At the northern end of Néry, the 5th Dragoon Guards were not primary targets for the German guns, which were firing into the village and the fields to the south, where the Queen’s Bays and L Battery were quartered.

Very soon, orders arrived from Brigadier-General Briggs that Lieutenant-Colonel Ansell, the commanding officer of the 5th Dragoon Guards, was to take 2 squadrons of his regiment out on the Bethisy Road to block the attacking Germans on the left flank. The third squadron, with the regiment’s machine guns, was to defend the north-eastern corner of the village.

Ansell’s squadrons dismounted outside the village and met the advancing cavalrymen of the German 3rd Cavalry Brigade with a fire that stopped them in their tracks. Colonel Ansell was directing his troops from horseback, when he was shot dead.

Queen’s Bays at church parade in Aldershot before the Great War: Battle of Néry on 1st September 1914 in the First World War

The 5th Dragoon Guards remaining in Néry directed a devastating fire on the 2nd Cuirassiers, the left regiment of the German 3rd Cavalry Brigade. The German right flanking attack was repelled.

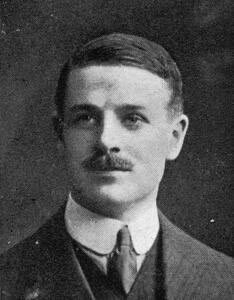

Lieutenant De Crespigny, Queen’s Bays, killed at the Battle of Néry on 1st September 1914 in the First World War

Queen’s Bays:

The opening German bombardment, that devastated L Battery, also fell on the Queen’s Bays, quartered in the field immediately to the west of L Battery, and in the same line of fire.

The bursting shrapnel killed numbers of the Bays’ horses, tethered in the field awaiting the move off once the fog cleared, and stampeded most of the remainder, sending them galloping down the main street of Néry and out into the countryside.

The Queen’s Bays soldiers hurried to line the edge of the lane that ran south from the village to the Sugar Factory, supporting L Battery with rifle and machine gun fire.

The German cavalrymen of the 18th Dragoons advanced on the Sugar Factory, while the Guards 3rd Machine Gun Company fired in support.

Lieutenant de Crespigny of the Queen’s Bays led his troop in an assault on the Sugar Factory. All the soldiers in the troop became casualties and de Crespigny was killed.

At around 9am, with the assistance of the 1st Middlesex, the Queen’s Bays captured the Sugar Factory and most of the Germans defending it were killed or taken prisoner.

German cuirassier regiment during peace time manoeuvres: Battle of Néry on 1st September 1914 in the First World War

1st Middlesex Regiment:

At around 5.30am on 1st September 1914, 1st Middlesex, of 19th Infantry Brigade, were in Santines, about 8 miles north of Néry. It was here, at 6am, that word was received from the 1st Cavalry Brigade that they were under attack. The battalion was ordered to march to Néry without delay. The acting commanding officer, Major Reynolds, immediately set off with the first ready company, D Company, and the machine section. On arrival in Néry, the Middlesex joined the line formed by the 11th Hussars on the eastern edge of the village and opened fire on the German guns, which ceased firing after about 2 minutes. ‘With bayonets fixed and a cheer the Middlesex men rushed across the small intervening valley (the ravine) and captured 8 of the guns which had been firing on the 1st Cavalry Brigade and L Battery RHA. With the exception of some 12 dead or badly wounded Germans the gun crews had fled. A few minutes later the German limbers were seen about 1,000 yards away and fire was at once opened on them, but they retreated and were seen no more. The guns were found to be undamaged, two of them loaded’ (from the Middlesex Regiment’s History, ‘The Diehards in the Great War’).

While the rifle company stormed across the ravine, the Middlesex machine gun section, commanded by Lieutenant Jeffard, moved to join the attack on the Sugar Factory, where what was described as the ‘Gun Escort’ was holding out.

German horse artillery during peace time manoeuvres: Battle of Néry on 1st September 1914 in the First World War

The final attack on the Sugar Factory was carried out by a mixed force of Queen’s Bays and Middlesex Regiment.

At the end of the action 1 ½ companies of 1st Middlesex advanced to Le Plessis Chatelain, where they captured the German divisional field ambulance, holding wounded soldiers from all 6 cavalry regiments of the 4th Division, gunners and machine gunners.

Farm in Néry occupied by C Squadron, 11th Hussars: Battle of Néry on 1st September 1914 in the First World War

I Battery, RHA:

I Battery, RHA, attached to the 4th Cavalry Brigade at Verberie, arrived at the west of Néry and came into action firing on the German batteries to the east of the village. The accompanying Household Cavalry Regiment moved towards Néry, a troop of the Royal Horse Guards attacking a party of dismounted German cavalry, the troop leader, Lieutenant Heath, being killed.

As the battle came to an end the German regiments left the battlefield.

Queen’s Bays after the action, with German prisoners from the Death’s Head Hussars: Battle of Néry on 1st September 1914 in the First World War

Conclusion to the Battle of Néry:

Some of the contemporary accounts of the battle are inconsistent. This may well be due to the limited time the British troops spent in Néry, with much of that time in the dark or in fog, in an unexpected, violent and confused battle.

The most important area of disagreement concerns the position of the German guns, whether east of the ravine or south east of Feu Farm, and whether in one single line or in two separate groups, one in each of these positions.

A significant indicator is the description of the attack by the Middlesex Regiment quoted above; ‘crossing the ‘small intervening valley’ (presumably the ravine) and finding 8 German guns on the far side’. This would place the main German gun-line to the east of the ravine, and would allow for a further 4 guns to have been in position to the south east of Feu Farm, with these guns being the ones that were taken out of battle. On the other hand, all 12 of the German guns may have been in the position assaulted by the Middlesex, with 4 of the guns being removed by the teams seen at 1,000 yards by the Middlesex.

11th Hussars in France: Battle of Néry on 1st September 1914 in the First World War: picture by Harry Payne

C Squadron of the 11th Hussars carried out a mounted attack at the end of the battle which took them through a German gun-line. It seems likely that the route of the 11th Hussars attack was along the back of the ravine, from south to north, and that it passed through this gun-line while the Middlesex were still negotiating the ravine, and moved on towards Plessis Le Chamberlain before the Middlesex emerged from the ravine and stormed the gun-line for the second time, leaving each regiment in the belief that it had captured the German guns. (Sources say that C Squadron crossed the ravine. This seems unlikely. Tailby’s patrol crossed the ravine before the battle began, but only with great difficulty and by taking a zig-zag path. The Middlesex account makes no mention of the hussars crossing the ‘small intervening valley’. The 11th were well aware of the ravine and would have found it much quicker to ride round the southern end.)

11th Hussars at the Battle of Néry on 1st September 1914 in the First World War: picture by Harry Payne

Lieutenant Norrie, of the 11th Hussars, gave a description of the charge at a symposium held in Woolwich in 1967. Norrie claimed the capture of the German guns for the 11th Hussars. Norrie said that the 11th Hussars were followed up by men from the Middlesex. He also stated that he thought the German guns were all together and positioned south-east of Feu Farm.

The Middlesex history makes no mention of the 11th Hussars being involved in the capture of the 8 guns taken on the far side of the ‘small intervening valley’.

4 German guns were found and taken the next day by British troops, well to the south west of Néry and were identified as guns from the German 4th Cavalry Division.

German uhlan regiment during peace time manoeuvres: Battle of Néry on 1st September 1914 in the First World War

Casualties at the Battle of Néry:

There is uncertainty over the British casualties. It would seem that 8 officers and 47 soldiers were killed. Numbers of wounded soldiers were left in Néry and captured by the Germans.

The numbers of German casualties are unknown.

L Battery is reported to have lost 150 horses killed. The Queen’s Bays are reported to have lost a similar number killed or bolted and not recovered. Many of the Bays’ bolted horses were recovered by other British regiments around the countryside and returned. 5th Dragoon Guards and 11th Hussars lost a small number of horses.

British soldier from 2nd Cavalry Brigade on a German horse captured during the Battle of Néry on 1st September 1914 in the First World War

Aftermath to the Battle of Néry:

After the battle, the German 4th Cavalry Division, in a state of disorganisation, moved off towards the Automne River to the north, with the intention of re-joining the II Cavalry Corps. The divisional advance guard was fired on by British infantry of 11th Brigade, from the far side of the Automne River. The German Division turned east towards Glaignes, but received reports that the British were around Crépy.

Garnier’s division ended up marching south-west towards Rosières. The division split up to avoid being attacked by British units, that were retreating in the same area. During the course of finding their way back to German lines, the remaining 4 guns were abandoned and taken by the British.

It was some time before Garnier’s Cavalry Division was again fit for action.

Decorations and campaign medals for the Battle of Néry:

Victoria Crosses were awarded to Captain Bradbury (posthumously), BSM Dorrell and Sergeant Nelson, all of L Battery, RHA. Dorrell and Nelson were commissioned.

DSOs were awarded to Major Sclater-Booth, the battery commander of L Battery, and to Lieutenant Lamb, the machine gun troop commander of the Queen’s Bays.

DCMs were awarded to 2 of the Queen’s Bays machine gun troop, Privates Goodchild and Ellicock.

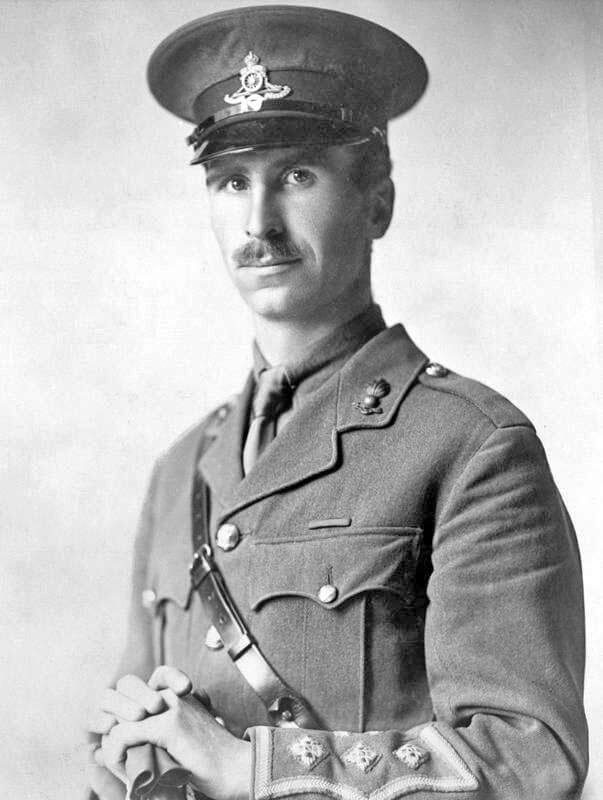

Captain David Nelson VC who won his VC as a sergeant at the Battle of Néry with L Battery Royal Horse Artillery: Battle of Néry on 1st September 1914 in the First World War

The French Legion d’Honneur was awarded to Lieutenant Colonel Wilberforce, the commanding officer of the Queen’s Bays, Lieutenants Lamb and Heydeman of the Queen’s Bays and Lieutenant Gifford of L Battery, RHA.

Victoria Crosses of Bradbury, Dorrell and Nelson held in the Imperial War Museum: Battle of Néry on 1st September 1914 in the First World War

The French Medaille Militaire was awarded to Corporal Short of the Queen’s Bays and Gunner Darbyshire and Driver Short of L Battery, RHA.

11th Hussars escorting the German Crown Prince before the Great War after he had been appointed Colonel of the 11th Hussars: Battle of Néry on 1st September 1914 in the First World War

Anecdotes and traditions from the Battle of Néry:

- As yet another indicator of the nature of this war, it was the machine guns on each side that dominated the battlefield. Many of the casualties in L Battery, both human and equine, were caused by the German Guard Machine Gun Company. It seems likely that the decimation of the German gun crews was largely brought about by the fire from the 11th Hussars machine guns, later joined by the Middlesex machine guns. The machine gun troop of the Queen’s Bays played a major part in subduing the Germans occupying the Sugar Factory and in repelling the advance of the German 17th Cavalry Brigade, reflected in the number of members of the troop who received a mention in despatches (8) and Lieutenant Lamb’s DSO.

- L Battery’s guns were all recovered and repaired in the artillery workshops. The surviving personnel returned to Woolwich and a new L Battery constituted. The immediate artillery support for 1st Cavalry Brigade was provided by dividing I Battery in two (it had 8 guns after absorbing the surviving guns from another battery) and naming the new 1st Cavalry Brigade battery, ‘Z Battery’. In September 1914, H Battery, RHA, arrived from Britain and took over from Z Battery.

- In 1926, when batteries of the Royal Artillery and the Royal Horse Artillery were given names, L Battery was named L (Néry) Battery.

- Although F Gun was the gun manned by Bradbury, Dorrell and Nelson, it is C Gun that is preserved in the Imperial War Museum in London, with the title the ‘Néry Gun’. On 11th November, each year, a member of the museum staff places a memorial poppy on the gun. The Imperial War Museum also holds a wagon used by L Battery, now displayed in the Land Warfare Gallery at Duxford.

- Captain Edward Bradbury of L Battery, RHA, awarded a posthumous Victoria Cross for his role at Néry, was a keen rider. Before the First World War, Bradbury came third in the Royal Artillery Gold Cup on his horse, ‘Sloppy Weather’. In 1911 he rode in the Punchestown Festival in Ireland

- After Néry, the Royal Horse Artillery abandoned the practice of ‘dropping poles’ when teams were harnessed and awaiting a move. At Néry, if L Battery’s teams had not ‘dropped poles’, the guns could have been driven off as soon as the German bombardment began. When the horses tried to move, the ends of the poles were driven into the ground, bringing the teams to a halt.

- Another change made was that RHA batteries were issued with high explosive shells as well as shrapnel, in a ratio of 50:50.

- The 8 guns taken at Néry were the first German guns captured by the BEF in the War. Teams were improvised and the German guns removed from the battlefield.

- Lieutenant Maurice Hill, of the 5th Dragoon Guards, was left for dead in a field outside Néry, when the Brigade continued its retreat, on 1st September 1914. Later that day, a young French woman visiting the village found Hill and realised that he was still alive. The woman took Hill to her parents’ house in Néry. Hill was concealed and handed to French troops, when they re-occupied the area later in the month. He had been reported dead and his identification disc taken from him by the regiment. Hill recovered consciousness, but could remember nothing. The French discovered Hill’s identity by writing to his boot maker, quoting the number on his boots. Hill eventually made a slow but full recovery.

- Lieutenant-Colonel Ansell’s son, Michael, followed his father into the 5th Dragoon Guards, which in 1922 became, on amalgamation, the 5th Inniskilling Dragoon Guards. Michael commanded the Lothian and Border Yeomanry, the mechanised regiment of 51st Highland Division, at St Valery in 1940. Michael Ansell was accidentally shot and blinded by British troops. After the Second World War, Michael Ansell became the driving force behind British and International Show Jumping.

References for the Battle of Néry:

The Affair at Néry by Patrick Takle: a comprehensive review of all the available accounts of the battle from British, German and French sources published by Pen and Sword Books Ltd.

Néry, 1914: The Adventure of the German 4th Cavalry Division on the 31st August and the 1st September by Major A. F. Becke; published by Naval and Military Press.

Mons, The Retreat to Victory by John Terraine, published by Pen and Sword Books Ltd.

The First Seven Divisions by Lord Ernest Hamilton.

The Official History of the Great War by Brigadier Edmonds August-October 1914: in CD Rom from the Imperial War Museum.

The previous battle in the First World War is the Battle of Heligoland Bight

The next battle in the First World War is the Battle of Villers Cottérêts