The second major battle of the First World War for the British Expeditionary Force; fought on 26th August 1914, the BEF escaped the advancing German First Army

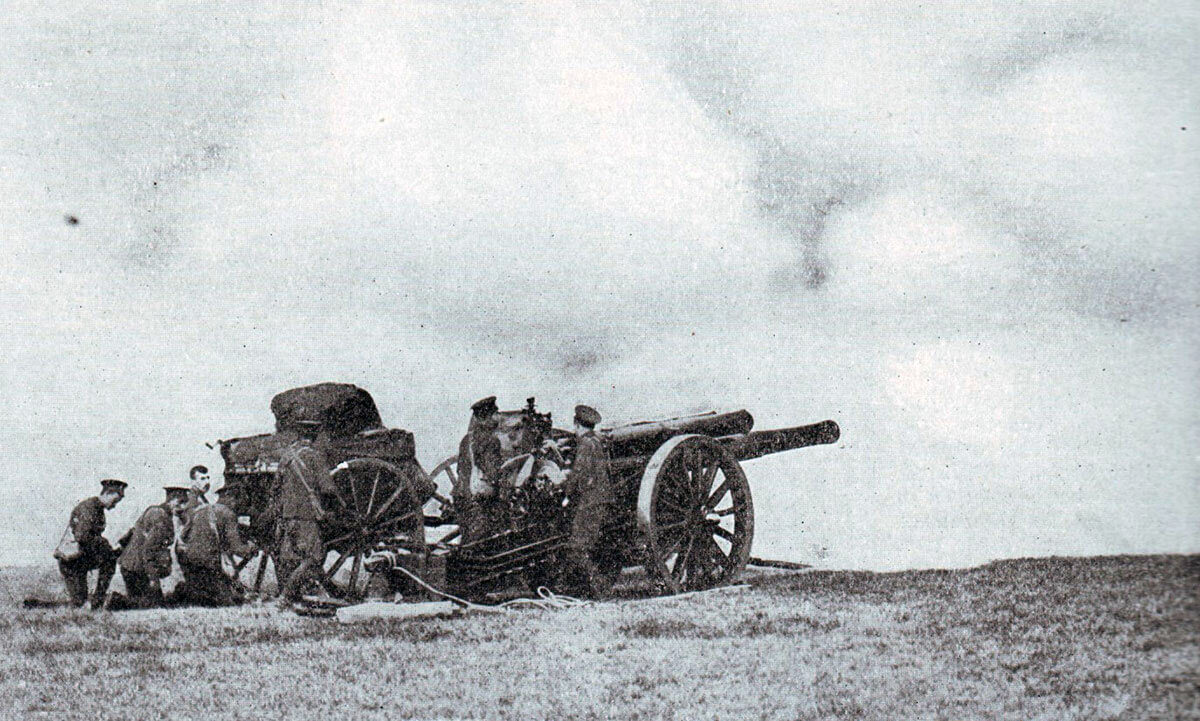

Battery of British Royal Field Artillery 18 pounder field guns moving up: Battle of Le Cateau on 26th August 1914 in the First World War

The previous battle in the First World War is the Battle of Landrecies

The next battle in the First World War is the Battle of Le Grand Fayt

Date of the Battle of Le Cateau: 26th August 1914.

Place of the Battle of Le Cateau: In Northern France, to the south east of Cambrai.

War: The First World War known as the ‘Great War’.

Contestants at the Battle of Le Cateau: The British Expeditionary Force (BEF) against the German First Army.

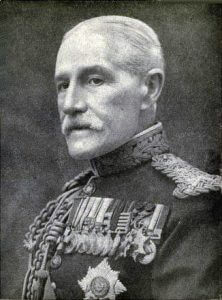

General Sir Horace Smith-Dorrien commanding British II Corps: Battle of Le Cateau on 26th August 1914 in the First World War

Commanders at the Battle of Le Cateau: Field-Marshal Sir John French commanding the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) with Lieutenant-General Sir Douglas Haig commanding I Corps and General Sir Horace Smith-Dorrien commanding II Corps, against General von Kluck commanding the German First Army.

Size of the Armies at the Battle of Le Cateau:

The BEF comprised 2 corps of infantry, I and II Corps, the 4th Division, the 19th Independent Infantry Brigade and the Cavalry Division; 110,000 men and 330 guns.

The British formations engaged in the Battle of Le Cateau were: II Corps: 37,000 men, 4th Division: 18,000, 19th Brigade: 4,000 and the Cavalry Division (less 5th Brigade): 9,000:

Total: 68,000 men.

General von Kluck, commanding the German First Army: Battle of Le Cateau on 26th August 1914 in the First World War

General von Kluck’s First Army comprised 4 corps and 3 cavalry divisions; 160,000 men and 550 guns.

Winner of the Battle of Le Cateau:

While the German First Army failed to envelope the BEF and defeat it, as von Kluck planned, the BEF continued to retreat and some bodies of infantry from the British II Corps failed to receive the orders to withdraw and were overwhelmed. The British lost 25 guns in the battle.

Uniforms and equipment at the Battle of Le Cateau:

See this section in the ‘Battle of Mons’.

Background to the Battle of Le Cateau:

See this section in the ‘Battle of Mons’.

The BEF at this stage in the Great War comprised around 30% current regular soldiers and 70% reservists with previous service in the Regular British Army. The British Army was the only major European army with recent experience of active service; in South Africa in the Boer War from 1899 to 1901 and on the North-West Frontier of India. The German Army had not fought a war since the Franco-Prussian War in 1870-1.

In these early battles of the Great War, the British soldiers outfought the Germans, although forced to retreat by pressure of numbers and the withdrawal of the French armies on their flanks. The British units’ ability to move about the battlefield in cover, and their facility to deliver high rates of accurate rifle fire repeatedly enabled them to repel attacks by massed German infantry. The British artillery units consistently provided support to the infantry with accurate gunfire, while manoeuvring about the battlefield with speed and resource.

This was the force the Kaiser described as a ‘Contemptible Little Army’. German officers were stunned by the way the British troops brought the German attacks to a standstill time and again.

During the course of 1914, the old British army melted away as the casualties caused by artillery, machine gun and rifle fire mounted, until the ‘Contemptibles’ were largely gone, to be replaced by the new mass British Army of war-time volunteers and conscripts.

The courage and technical ability of the units in the BEF during 1914 is striking.

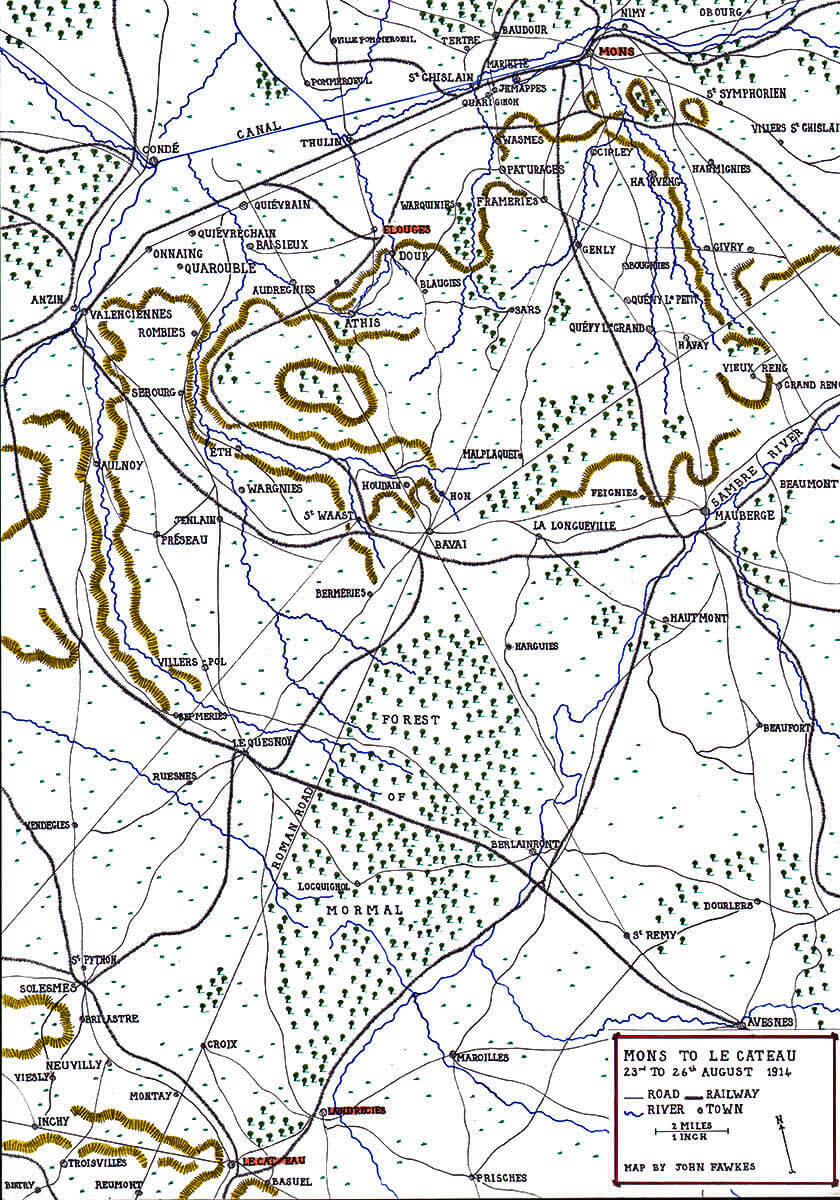

Map of the British ‘Mons to Le Cateau’ march: Battle of Le Cateau on 26th August 1914 in the First World War: Map by John Fawkes

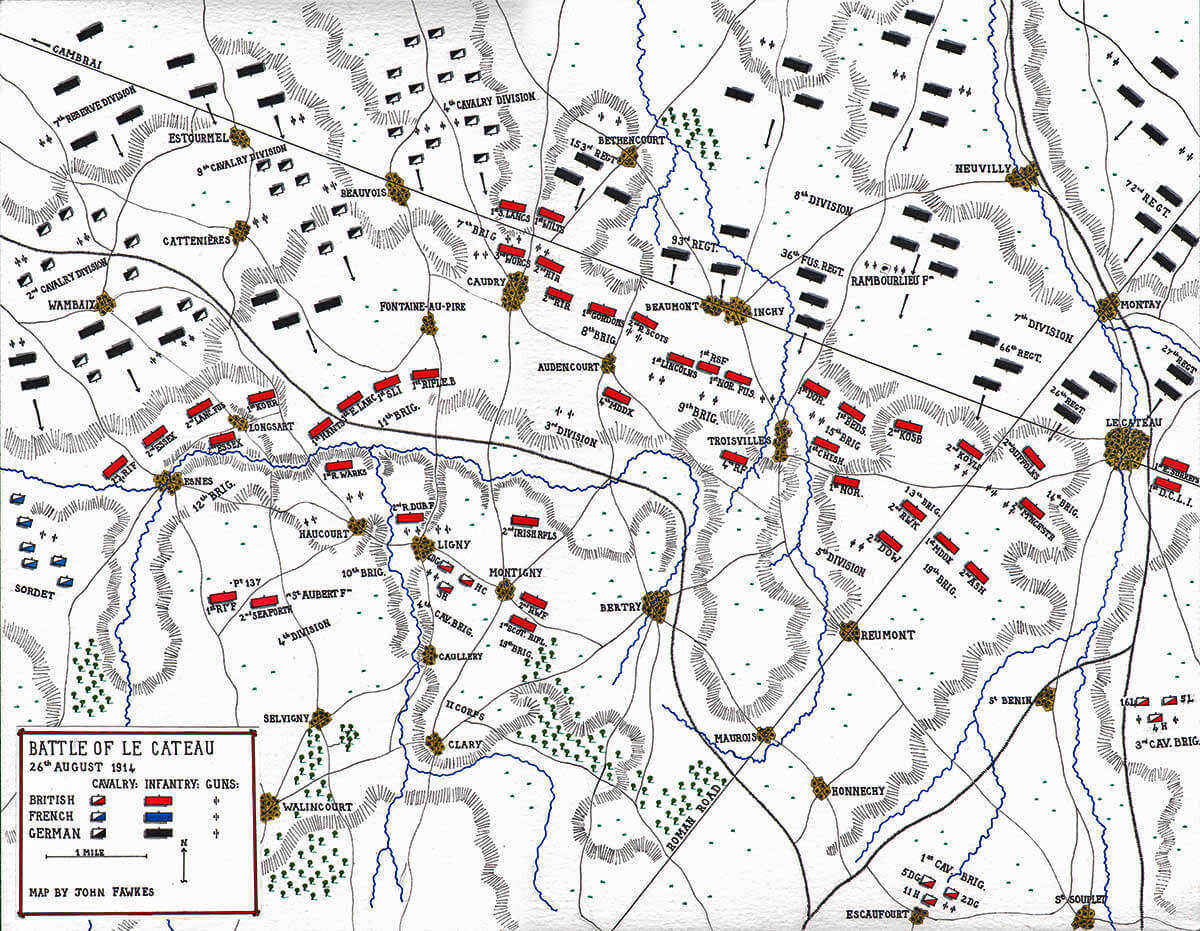

Account of the Battle of Le Cateau: (for full unit names from abbreviations see index at the end of BEF Order of Battle)

The BEF, following its withdrawal from the positions on the Mons (or Condé) canal, on the morning of 25th August 1914 lay in a line to the east and west of Bavai, some 15 miles to the south-west of Mons, with I Corps to the east of Bavai, and II Corps to the west. The Cavalry Division with 19th Independent Infantry Brigade, which was now under the command of the Cavalry Division, lay to the west of II Corps on the British left flank, less the 5th Cavalry Brigade, which was attached to I Corps on the British right.

A further British division, the 4th, arrived by train at Le Cateau and neighbouring stations by 24th August, and moved forward to Solesmes, to the south-west of Bavai, its duties in England having been taken over by Yeomanry and Territorial units. The 4th Division was hampered by having arrived without its divisional cavalry, heavy artillery battery or signals. When the divisional cavalry did arrive, they were transferred to the Cavalry Division, leaving the division without the ability to carry out basic reconnaissance.

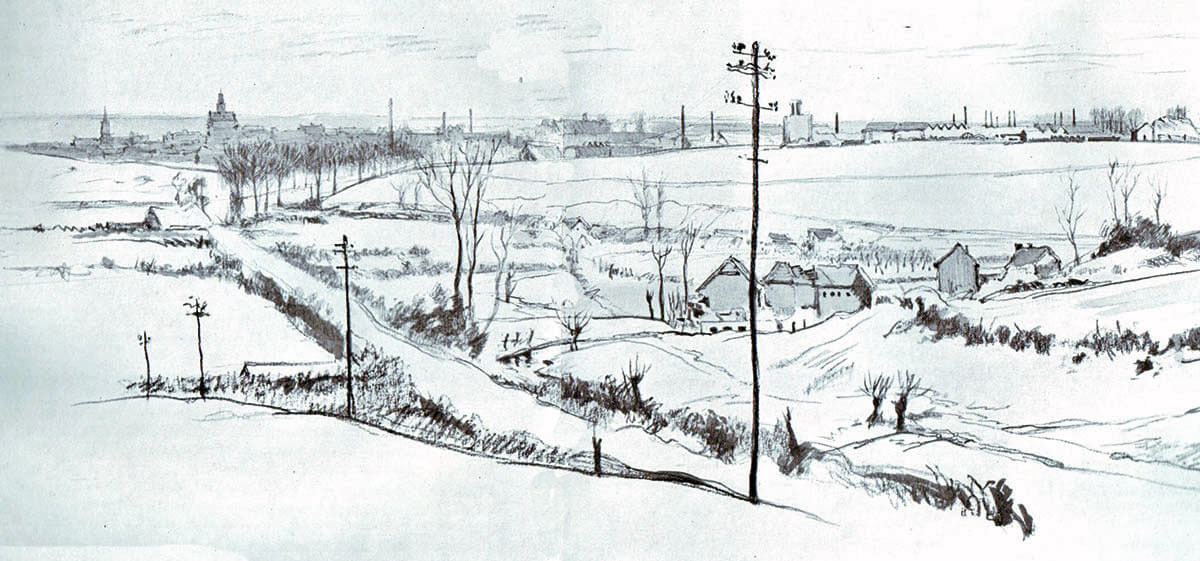

Aerial view of the southern end of the Forest of Mormal: Battle of Le Cateau on 26th August 1914 in the First World War

Sir John French’s plan was for the BEF to retreat in a south-westerly direction, to positions at Le Cateau. In planning this move, Field Marshal French faced a major problem. To the south of Bavai lay the large Forest of Mormal. No roads crossed the forest in the direction the BEF was to march, although 2 roads, one main, and a railway line ran through the forest from west to east. The difficulty was in allocating the routes on either side of the forest to his two corps, and, at the same time, ensuring their security with such a large area of forest between them.

The Forest of Mormal is bounded on its western border by the Roman Road, that runs straight from Bavai in a south-westerly direction, crossing the road from Le Cateau to Cambrai a mile to the west of Le Cateau. Beyond this junction the Roman Road continues straight on to St Quentin.

On the eastern side of the Forest of Mormal lies the Sambre River, and a number of roads running roughly north-east to south-west, which cross and re-cross the Sambre.

Field Marshal French directed the II Corps to march down the western side of the Forest of Mormal, with the Cavalry Division on its western flank, and directed the I Corps to march down the eastern side of the forest, passing through Landrecies and on to Le Cateau.

Village house acting as Head Quarters for British I Corps with sentries from 1st Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders: Battle of Le Cateau on 26th August 1914 in the First World War

Once it reached the end of this march, the I Corps was directed to take up defensive positions behind the Le Cateau to Cambrai road, along the high ground to the west of Le Cateau, while the II Corps took up positions further to the west. The 4th Division would join the withdrawal from Solesmes, and take the extreme left of the BEF line, supported by the Cavalry Division.

Complications were immediately caused by the movement of French formations. General Joffre, the French Commander-in-Chief ordered General Sordet’s French Cavalry Corps to move west, across the rear of the BEF, to take up positions on the left flank of the BEF. Sordet was consequently moving at right angles across the BEF’s line of withdrawal.

There was a lack of co-ordination between the British and French high commands, with the result that a number of French infantry divisions used the same roads and river crossing points as the I Corps to the east of the Forest of Mormal, causing confusion and delay.

The German pursuit of the BEF was handicapped by the continuing belief of the German High Command, that the BEF was withdrawing to the Channel ports in the north-west, rather than complying with the French withdrawal, and retreating in a south-westerly direction.

As the British retreat began, the 5th Division of the British II Corps had difficulty disengaging from the German units in the area of Bavai, before moving onto the Roman Road and marching off to the south-west. The II Corps’ other division, the 3rd, took the road through Le Quesnoy, with the Cavalry Division on its western flank. Its 7th Brigade provided the general corps rear guard.

The 4th Division, after arriving by train at Le Cateau, moved to positions north of Solesmes, to provide support for the II Corps in its march down the western side of the Forest of Mormal.

As the British I Corps moved south west, down the eastern side of the Forest of Mormal, the 4th (Guards) Brigade of the 2nd Division saw action with the pursuing German troops in Landrecies at the south-western point of the Forest of Mormal.

‘Good bye Old Man’, a British gunner leaves his dying horse: Battle of Le Cateau on 26th August 1914 in the First World War: picture by Fred Matania

Landrecies:

As the I Corps reached the southern end of the Forest of Mormal, British troops were posted to guard the Sambre River crossings at Maroilles and Landrecies.

It was in these places that the German pursuit caught up with I Corps.

The troop of the 15th Hussars holding the bridge at Maroilles was driven back, in a surprise attack by German infantry equipped with a gun. Attempts to retake the bridge by a company of 1st Royal Berks failed in the dark.

4th (Guards) Brigade at Landrecies were led to believe that the reports then circulating, of the presence of German troops, were incorrect, by cavalry patrols who found no sign of them.

At 7.30pm on 25th August 1914, No 3 Company of 3rd Coldstream Guards, on piquet with 2 machine guns at the entrance to Landrecies, was subject to a surprise attack by German troops. Re-enforced, the Coldstream battalion, supported by 2nd Grenadier Guards, repelled a number of attacks by German infantry, who were attempting to take the town.

At around 8.30pm German artillery opened fire on Landrecies, setting fire to a haystack which illuminated the British Guards’ positions, until put out by Lance Corporal Wyatt of the Coldstream (for which, in addition to subsequent brave conduct, he received the Victoria Cross).

The German infantry renewed their attacks on the Foot Guards in Landrecies, supported by artillery, until a howitzer of the 60th Battery RFA was brought up and silenced the German guns.

In the early hours the Germans withdrew. Casualties on each side seem to have been around 120 men.

The action at Landrecies received a great deal of publicity in Britain, probably out of proportion to its size and significance.

The Battle of Le Cateau:

In the early hours of 26th August 1914, Sir John French changed his proposed dispositions for the BEF. He allocated defence of the positions to the south of the road to the west of Le Cateau to II Corps, the Cavalry Division and 19th Brigade, instead of to I Corps. He re-directed I Corps to positions to the east and south-east of Le Cateau.

The German attack on Landrecies caused considerable alarm to General Haig, commanding I Corps. He requested assistance from II Corps or 19th Brigade, which could not be provided. As an alternative the 1st Division was moved to support the 2nd Division, and the line of retreat for I Corps was changed to a southerly rather than a south-westerly direction, taking it away from Le Cateau. This move opened a substantial gap, of about 8 miles, between the two British corps, which would enable the German First Army to move unchecked around the right flank of the II Corps.

During the night of 25th/26th August 1914, the transport of II Corps moved through Solesmes, heading south towards the Le Cateau-Cambrai road. German artillery opened fire on the 3rd Division rearguard, comprising the 2nd South Lancashires and 1st Wiltshires of the 7th Brigade, which fell back during the night.

The 4th Division held the high ground to the south of Solesmes, while the troops of the 3rd Division cleared the town.

During the night of the 25th August, units of the BEF reached the Le Cateau area; 19th Infantry Brigade, some of the II Corps units, and 1st and 3rd Cavalry Brigades, the troops and horses in a state of exhaustion after the long march and the days of action or alert.

There was a considerable traffic jam on the narrow road leading into the town. Fortunately for the II Corps, the pursuing German formations stopped to bivouac around Solesmes, leaving the British to sort themselves out in Le Cateau during the night.

Many of the II Corps units headed straight for their positions south of the Le Cateau-Cambrai road, without going through Le Cateau.

There was considerable activity in the Le Cateau area during the night. General Sordet’s French Cavalry Corps passed behind II Corps and bivouacked at Walincourt, providing significant support for the BEF’s left flank.

Early in the night, II Corps’ brigades started to come into position; 5th Division between Le Cateau and Troisvilles, with 2 battalions on the heights to the east of Le Cateau. 3rd Division was still on the march to its positions to the west of the 5th Division.

Le Cateau seen from the Honnechy Road to the south: Battle of Le Cateau on 26th August 1914 in the First World War

Field Marshal French’s order to continue the retreat:

During the evening of 25th August, Sir John French decided that there should be no stand on the Le Cateau position, and that the BEF should continue its retreat early the next morning, with the Cavalry Division acting as a covering rearguard. Orders were issued to this effect, but did not reach his senior commanders until late evening of the 25th August.

General Smith-Dorrien was forced to inform Sir John French that the regiments of his 3rd Division were still coming in, and could not be ready for a move in the early hours of the next day, as required by French’s new order. In addition, General Allenby reported that his cavalry brigades were too scattered and exhausted to cover a general retreat, without a period of consolidation and rest.

General Smith-Dorrien reported that he would have to stand his ground on the Le Cateau positions, and hit the Germans hard before continuing the retreat. Smith-Dorrien asked Allenby to support his stand with the Cavalry Division and 19th Infantry Brigade, which Allenby agreed to do.

Officers of 1st Cameronians before the battle of Le Cateau on 26th August 1914 in the First World War

It was expected that the 4th Division, under General Snow, would remain in position on the left flank of II Corps during this stand.

Sir John French endorsed this change of plan, while emphasising that II Corps must retreat as soon as it could.

No change was made to the plan for I Corps, which resumed the retreat on 26th August, leaving a widening gap between I and II Corps, which the Germans were to exploit, but insufficiently.

General Sordet was informed that II Corps was making a stand, and asked to support it with his French Cavalry Corps, which he readily agreed to do.

The ensuing battle was confused, due substantially to the repeated and late change of orders.

French civilians had dug an embryonic and intermittent trench line to the south of sections of the Le Cateau-Cambrai road. This line was used by several British infantry regiments as the basis for their positions. Due to the lack of time for preparation, many of the artillery batteries were forced to fight their guns in the open, either in or close behind the infantry line. This left them exposed, and made extraction, once the retreat was resumed, extremely difficult. It also brought down additional German gunfire on the infantry.

Incidents in which officers and men showed great gallantry and resource in bringing up the horsed gun teams, to extract the guns from action, under the noses of German artillery and infantry, are a striking feature of these battles of the 1914 retreat; Mons and Le Cateau. A substantial number of the gallantry awards in the early months of the War were for such incidents.

A Royal Engineers wireless cart operating during peacetime manoeuvres: Battle of Le Cateau on 26th August 1914 in the First World War

Communication was a particular problem. Orders were passed by officer or orderly on horse, bicycle or by car if there was a road route available. In some situations, communication might be possible by telephone, particularly by using the French railway telephone system. Wireless communication was limited to higher formations and unreliable.

While the 4th Division was at Solesmes, the divisional artillery, other than the heavy battery, arrived and joined the division. Preparations were made for the division’s march to the area north of Haucourt, from Fontaine au Pire to Wambaix, which was its allocated position in the Le Cateau line, to the left of II Corps.

With varying degrees of difficulty, the brigades of the 4th Division reached their appointed defensive positions during the night of 25th/26th August; 11th Brigade just south of Fontaine au Pire, 12th Brigade around Longsart and Esnes and 10th Brigade as the divisional reserve around Haucourt.

Of II Corps, the 3rd Division held the line to the east of the 4th Division, with the order of brigades from west to east; 7th Brigade at Caudry, 8th Brigade to the east of Caudry, and then 9th Brigade.

The 5th Division held the line from Troisvilles eastwards, with 15th Brigade, 13th Brigade in the ground up to the Roman Road, and 14th Brigade holding the hillside leading up to the north-west side of Le Cateau, with 2 battalions, 1st East Surreys and 1st DCLI on the hillside to the east of Le Cateau.

Soldiers of 1st Cameronians, 19th Brigade: Battle of Le Cateau on 26th August 1914 in the First World War

19th Brigade in the early hours of 26th August was still making its way through Le Cateau. Its position during the battle was; half of 19th Brigade (2nd RWF and 1st Scottish Rifles) held Montigny behind the 7th Brigade. The other half, 2nd Argylls and 1st Middlesex supported 14th Brigade on II Corps’ right flank to the south of Le Cateau. Later 2nd RWF and 1st Scottish Rifles were required to march to the eastern flank of II Corps, and then back again to Montigny to support 3rd and 4th Divisions.

The Cavalry Division; 1st and 3rd Brigades were south of Le Cateau. 4th Brigade supported the 4th Division at Caullery. RHA Batteries supported the forward line; E and L south of Le Cateau and I Battery right at the front, north of Caudry, with 1st South Lancs.

The I Corps was to the south-east of Le Cateau and took no part in the battle.

1st Gordon Highlanders holding the line east of Caudry, on 26th August 1914, during the Battle of Le Cateau in the First World War: picture by William Barnes Wollen

The battle of Le Cateau begins;

At about 6am, the German artillery opened a barrage on the 4th Division transport which was still making its way through Fontaine au Pire, at the western end of the British line. Due to the division’s lack of divisional cavalry there was no warning of this attack which took the division by surprise. The transport continued on its route through Ligny, and to the south.

It was around this time that the brigades of 4th Division finally took up their positions in the villages around Haucourt. A substantial gap existed between the right of the division and the left flank of its neighbour, 7th Brigade of 3rd Division at Caudry.

The new order to stand fast reached 4th Division Headquarters at Haucourt, before the German attack began.

It was around 5.30am that General Snow issued his order to the 4th Division, cancelling the continuation of the retreat and directing his brigades to occupy the battle positions previously allocated. By the time the order reached the forward units, the infantry were ‘at it hammer and tongs’ with the attacking Germans (the words of one of the staff officers conveying the order).

Where the order cancelling the continued retreat by II Corps and its accompanying formations was received, it arrived from 4am on 26th August onwards. This meant that there was little or no time to reconnoitre the ground it was proposed to defend, or to prepare positions.

On the extreme right of II Corps, to the east of Le Cateau, 1st East Surreys and 1st DCLI of 14th Brigade did not receive the order to stand fast, and formed up ready to march through Le Cateau to the south-west, as did 19t Brigade.

British infantry marching through a French village in August 1914: Battle of Le Cateau on 26th August 1914 in the First World War

The positions held by II Corps at the Battle of Le Cateau:

To the west of Le Cateau, the 2nd Suffolks of 14th Brigade, 5th Division, occupied the hill above the town. The battalion received the stand fast order as it was about to move off, and was forced to improvise its defensive position, much of it exposed.

The 2nd Suffolks were to play a key role in the battle. The battalion’s tenacious hold on the high ground overlooking Le Cateau from the west, was crucial in enabling the 5th Division to extract and march away down the Roman Road to the south-west later in the day. A substantial effort was made by the German infantry and artillery during the battle to dislodge the Suffolks. The Suffolks were provided with re-enforcement and support, with great difficulty and high casualties, by the Argylls of 19th Brigade and the Manchesters of 14th brigade. A memorial now marks the area of the Suffolk positions.

At the beginning of the battle, the 2nd Manchesters were on the hillside overlooking the river valley to the south of Le Cateau.

Next to 2nd Suffolks in the line facing north, were the battalions of the 13th Brigade; 2nd KOYLI and 2nd KOSB, supported by 2nd Duke of Wellington’s and 1st RWKs. Artillery batteries supported these battalions, as they did with each of the frontline brigades.

The next in line to the west was the 15th Brigade; 1st Bedfords, and the 1st Dorsets in front of Troisvilles, with 1st Norfolks and 1st Cheshires in reserve (the 1st Cheshires had suffered substantial casualties the previous day at Audregnies).

West of Troisvilles was the 9th Brigade; 1st Northumberland Fusiliers and 1st Lincolns, with 1st Royal Scots Fusiliers and 4th Royal Fusiliers in support.

The 8th Brigade was in front of Audencourt; 2nd Royal Scots, 1st Gordon Highlanders and 2nd Royal Irish Regiment, with 4th Middlesex in support.

The 7th Brigade was in front of Caudry; 2nd Royal Irish Rifles, 1st Wiltshires and 1st South Lancashires, with 3rd Worcesters in reserve in the town. Again, batteries including 2 guns from ‘I’ Battery RHA provided artillery support.

The headquarters of the II Corps lay at Bertry.

Of these formations, the 3rd Division received the notice of the decision to stand fast and fight earliest, and was able to take steps to strengthen its positions. The artillery had the opportunity to dig positions to protect its guns.

The positions held by the 4th Division at the Battle of Le Cateau:

In the line of the 11th Brigade, south of Fontaine au Pire, were 1st Rifle Brigade, 1st Somerset LI, 1st East Lancashires and 1st Hampshires.

Soldiers of 1st East Lancashire Regiment outside Solesmes on 25th August 1914: Battle of Le Cateau on 26th August 1914 in the First World War

In the extended 12th Brigade line, based on Esnes, were 1st King’s Own, 2nd Lancashire Fusiliers, 2nd Essex and 2nd Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers.

The 10th Brigade was positioned around Haucourt in support; 1st Royal Warwickshires, 2nd Seaforth Highlanders, 1st Royal Irish Fusiliers and 2nd Royal Dublin Fusiliers.

Batteries provided artillery support for each brigade. In the case of 4th Division, its heavy battery was not present, depriving the division of the invaluable asset of RGA 60 pounder guns.

A 60 pounder gun of the Royal Garrison Artillery in action: Battle of Le Cateau on 26th August 1914 in the First World War

The beginning of the battle around Le Cateau:

The battle began in earnest at around 5am, with a heavy German bombardment of the battalions on the ridge to the immediate west of Le Cateau, 2nd Suffolks and 2nd KOSB, as dawn broke.

At the same time, German infantry infiltrated into Le Cateau and opened fire on the battalions waiting to pass through and continue the retreat; 1st East Surreys and 1st DCLI. There was considerable confusion.

These British units fell back through the town and formed a defensive position on high ground to the south east of Le Cateau, assisted by counter-attacks carried out by the East Surreys. The 3rd Cavalry Brigade, which was in the area, provided additional support.

At about 8am these 2 battalions moved across the valley to join the rest of 14th Brigade. On the way they caught the advancing German infantry in the flank, and drove them back into Le Cateau.

At around 7am German artillery positioned around Rambourlieux Farm, about 1 mile north of the Le Cateau-Cambrai road and opposite the 13th Brigade positions, began a bombardment. The British artillery and infantry returned the fire.

At around 8am, German Jӓgers began to scale the high ground above Montay and fire on the British gunners. This fire was returned by the Suffolks.

In the meantime, the East Surreys and the DCLI were fighting their way across the valley to Maurois, while the cavalry brigades withdrew to St Souplet in a south-westerly direction.

With the withdrawal of the East Surreys and the DCLI, Le Cateau and the high ground to its east was left clear for the German advance. German artillery was brought up onto this high ground, and fire opened on the 5th Division positions south of the Le Cateau-Cambrai road. These battalions and their supporting batteries were now subject to gunfire from the front and flank.

At 9.45am, the 2nd Argylls from 19th Brigade moved up from Reumont to support the Suffolks on the high ground to the west of Le Cateau.

At around 10am, German infantry began to advance in massed formations across the Le Cateau-Cambrai road. The troops were from the 66th and 26th Infantry Regiments of the 7th German Division. This attack was delivered against the 13th Brigade and the 2nd Suffolks, with those reinforcements that had managed to reach the Suffolks.

The British artillery and infantry fired on these formations, inflicting large numbers of casualties. The fire of the 108th Heavy Battery of the RGA, firing 60 pounders from positions just north of Reumont, was particularly effective.

Under the heavy fire of the British artillery and the rifle fire of the infantry, the Germans managed to move forward in small groups, covered by their own artillery and machine guns, around the Suffolks on the spur to the west of Le Cateau.

The Suffolks, suffering heavy losses, were supported by the KOYLI on their left flank, particularly by a KOYLI machine gun, by the batteries to their rear, and by companies from the Manchesters of their own brigade and the Argylls of 19th Brigade; the Argylls reaching the Suffolk positions at around midday.

The Germans brought 2 field guns up onto the high ground to fire directly into the British positions. Nevertheless, the British infantry on the extreme right stood fast, until ordered to withdraw later in the day.

German Krupp 77mm field gun, the standard German field gun in the First World War: Battle of Le Cateau on 26th August 1914 in the First World War

Troisvilles:

Further to the left, German columns were seen approaching the positions of the 13th and 15th Brigades of the 5th Division around Troisvilles from the early hours. British gunfire forced these columns to deploy into cover.

Audencourt:

From around 6am, a determined German effort was made to infiltrate a strong infantry force to the south of the villages of Beaumont and Inchy, in front of the British 8th and 9th Brigades of the 3rd Division. The heavy fire maintained by these brigades and their supporting batteries prevented the German movement from developing for some hours.

Caudry:

The British 7th Brigade held positions around the northern perimeter of the town of Caudry. At this point the British line was nearest to the straight Le Cateau-Cambrai road, and the 7th Brigade’s position was consequently an exposed one, particularly as there was a gap of around a mile between it and its neighbouring units of the 4th Division on its left, which were in any case angled back from the 3rd Division positions.

The battalions of the 7th Brigade did not receive the stand fast order until around 6am, by which time they were being subjected to a heavy German bombardment, and the German infantry were infiltrating on each flank.

The 7th Brigade had suffered a particularly trying retreat, with many parties of soldiers becoming separated from their units, leaving them under strength. One battalion, 2nd Royal Irish Rifles, had ended the long march to the area at Maurois, and only re-joined the brigade as the German attack began.

The attack was particularly heavy on 3rd Worcesters, holding the extreme left of the brigade’s position. Companies of the 2nd Royal Irish Regiment came forward from the 8th Brigade reserve to bolster the Worcesters, and the brigade held the German advance until late morning.

The German plan appears to have been to pin the centre of the British line, with bombardments and infantry attacks, while an encircling movement on each flank was conducted, with the aim of capturing the entire force. The only way this plan could be thwarted, with the limited strength available to the BEF, was by retreating, yet again, out of the trap. Before doing so, it was necessary to inflict a severe check on the Germans, to prevent them from following up the British retreat too closely, and to enable the British formations to disengage and get away.

The 4th Division:

On the extreme left of the BEF’s positions, the 4th Division, positioned between Fontaine au Pire, Esnes, Haucourt and Ligny, with 4th Cavalry Brigade, lay in the path of the German western encircling force.

The 4th Division had no divisional cavalry or cyclist company to carry out reconnaissance to its front, and relied upon reports from the French cavalry, which stated that there were no German units nearby.

The first sign of a German attack was the bombardment of the 4th Division transport, as already described.

At around 6am, German machine guns opened fire on the 12th Brigade, positioned to the north of Haucourt. This fire caught the 1st King’s Own as they arrived from Haucourt, with the regiment still in column of companies. The King’s Own returned the fire, but then came under bombardment from a number of German batteries, that had unlimbered between Wambaix and Cattenières. The King’s Own suffered a substantial number of casualties, around 400, including the death of their commanding officer. However once rallied in cover, the regiment silenced the German machine guns with effective rifle fire.

To the left of the King’s Own, the 2nd Lancashire Fusiliers came under attack from German machine guns, artillery, cavalry and infantry. With assistance from 2nd Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers, the Lancashire Fusiliers held their own, even though it was estimated that the regiment was combating 23 German machine guns, with only 2 machine guns.

On the extreme left of the British line, the German 7th Jägers advanced across a cornfield, expecting to penetrate behind the British positions. These troops were met with rifle fire from the Inniskillings and forced back with heavy loss.

A consequence of the late receipt of the ‘stand fast’ order by the 4th Division was that the divisional artillery took time to take up positions in support of the infantry brigades, and to come into action. This was done with a minimum of delay and valuable support was eventually provided by the guns.

British 18 pounder field guns in action: Battle of Le Cateau on 26th August 1914 in the First World War

The 11th Brigade was given a break from the German artillery fire, which was now diverted to the British guns that were firing on them. The 12th Brigade was given the opportunity to re-organise its defensive positions by the gunfire of XIV Brigade RFA.

The German infantry renewed its attack on the Lancashire Fusiliers, but was repelled by concentrated rifle fire.

By around 10am the German surprise attack on the 12th Brigade had spent its initial force. The brigade was drawn back, and a new and firmer line established from Esnes through Haucourt to the edge of Ligny, which was held by the 10th Brigade.

Brigadier General Haldane, commanding the 10th Brigade, was ordered to secure the extreme left flank of the division, and indeed of the BEF. He did so by despatching 1st Royal Irish Fusiliers and 2nd Seaforth Highlanders, to hold the ridge between St Aubert Farm and Point 137, half a mile south of Harcourt.

On the right of the 4th Division’s position, the 11th Brigade, and in particular the Lancashire Fusiliers, was subjected to heavy German artillery fire and repeated attempts to infiltrate infantry down the flanks of the brigade. The brigade right flank was held by 1st Rifle Brigade and 1st Somerset LI. On the left flank, 1st Hampshires attempted a counter attack, but the Germans were too strong in artillery and machine guns, and the attack had to be abandoned, after heavy casualties. The brigade hung on to its positions with great tenacity.

All along the British line to the west of Le Cateau, the infantry battalions, supported by the gun batteries, were holding on and were unshaken. However, around midday it became clear that the British II Corps and its accompanying formations must disengage and retreat, or be outflanked and surrounded.

French 75 millimetre guns in action against the Germans: Battle of Le Cateau on 26th August 1914 in the First World War

The British withdrawal from the Le Cateau position:

The need for the British II Corps to disengage from the battle and retreat was finally shown by the position of the Suffolk regiment on the right wing, on the high ground to the west of Le Cateau.

The Suffolks were exposed to heavy gunfire from German batteries to their front and to their flanks, and infiltration by German infantry around their flanks.

The only reserve available to II Corps was the 19th Infantry Brigade. Of the 4 battalions of that brigade, the 1st Scottish Rifles and 2nd Royal Welch Fusiliers had been moved to Montigny to support the 4th Division, and part of 1st Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders had already been committed to support the Suffolks, leaving only the rest of the Argylls and 1st Middlesex in reserve behind the 5th Division on II Corps’ right.

These units were pushed forward to support the Suffolks, the Middlesex moving up the line of the Selle River in the valley leading to Le Cateau. Although this was the route around II Corps’ vulnerable eastern flank, the German II Corps was not yet advancing in this direction. This left the 19th Brigade units free to fire on the infantry and machine guns attacking the Suffolks, thereby bringing heavy gunfire down on themselves, which put the Argylls’ 2 machine guns out of action.

At around midday on 26th August, General Smith-Dorrien conferred with General Fergusson, the GOC of 5th Division, at the divisional headquarters in Reumont and the decision to disengage and retreat was for the moment deferred.

At around 1pm, General Fergusson made the further assessment that the right of his division, of which the Suffolks were the key, was near to giving way. In addition, General Fergusson could see that German units were, belatedly, circling around his right flank from the direction of Bazuel. In the absence of significant re-enforcement, which was not available, his division would need to retreat.

At around 1.20pm General Smith-Dorrien gave General Fergusson permission to begin his withdrawal. At the same time, he ordered the 1st Scottish Rifles and 2nd Royal Welch Fusiliers to move from Montigny to Bertry, to assist in covering the withdrawal of the 3rd and 5th Divisions.

Directions were given by General Smith-Dorrien for the retreat in the order; 5th Division, 3rd Division and then 4th Division, with the Cavalry Division moving to the west of the infantry. The II Corps was to retreat towards St Quentin, 20 miles to the south-west of Le Cateau. The retreat would begin at the discretion of General Fergusson.

German infantry advancing up a hillside: Battle of Le Cateau on 26th August 1914 in the First World War

On the hill above Le Cateau, German infantry made rush after rush from the front and both flanks at the Suffolks, Manchesters and Argylls, being repeatedly repelled. The German buglers sounded the British ‘Cease Fire’, in attempts to persuade the British soldiers to surrender, to no avail. Finally, at 3pm the positions were overwhelmed with an attack from the rear.

General Fergusson issued the order to his 5th Division to retreat at 2pm, with the order reaching the forward brigades at around 3pm at the earliest.

While there was little difficulty in getting the retreat order to the brigade headquarters, it was another matter getting the order to the units in contact with the attacking German formations. Officers and orderlies carrying the order the last few yards, did so under fire from German infantry, and many were hit before reaching their destination. In several instances along the British line, regiments or companies failed to receive the order to retreat, and continued to hold and fight their positions.

The order was, of course, too late for the Suffolks, Argylls and Manchesters on the high ground overlooking Le Cateau.

The retreat order did not reach the 2 forward companies of the 2nd KOYLI. With the collapse of the position held by the Suffolks, Manchesters and Argylls on their right, the KOYLI were now the unit on the extreme right of the 5th Division line.

The first attack on the KOYLI comprised a force of German infantry, that came over the brow of the hill previously held by the Suffolks. The KOYLI waited until they were well down the side of the hill and unleashed machine gun and rifle fire upon them, driving them back over the hill.

The other British regiments to the left and rear of the KOYLI were beginning to retire, having received the retreat order; the 2nd KOSB (other than one company that failed to receive the withdrawal order and remained to be overwhelmed by the oncoming German infantry), 2nd Duke of Wellington’s and the 1st RWKs. This enabled the Germans to continue their attack on the KOYLI by renewing their move to the right rear of the battalion, also to the left rear, into the ground previously held by the KOSB, and also to their front.

Driver King hooking in horses under fire at the Battle of Le Cateau on 26th August 1914 in the First World War

The KOYLI firing line was commanded by Major Yate. Major Yate resisted until his 2 companies were overwhelmed and the survivors, including Yate, taken prisoner. The remnants of the battalion fell back, numbering that evening 8 officers and 320 rank and file, less than half the original strength of the battalion. The German advance was held up until around 4.30pm by the resistance of the KOYLI, giving the rest of the 5th Division a much needed period in which to disengage and retire.

In the Selle Valley, the German advance from the east was held up by a mixed force of Argylls, Middlesex and 2nd Royal Scots Fusiliers from 19th Brigade (the RSF had been transferred from the reserve to the 19th Brigade) with 59th Field Company, Royal Engineers. In addition, the 1st Cavalry Brigade, with E and L Batteries RHA, assisted in halting the German outflanking movement up the Selle valley.

The 19th Brigade infantry were forced back to the west, but continued to hold the German outflanking movement up the Selle Valley.

Driver O’Brien taking his gun out of action at the Battle of Le Cateau on 26th August 1914 in the First World War

Troisvilles:

The retreat for much of the 5th Division was through Troisvilles, entering the town via the ‘Sunken Road’ and past the ‘Tree’.

The positions to the north of Troisvilles were held by the 15th Brigade with the Bedfords and Dorsets in the line.

The 15th Brigade was not subject to attack until well into the afternoon of 26th August, there being little cover for any German advance from the Le Cateau-Cambrai road. The supporting artillery comprised the 119th, 120th and 121st Batteries (119th Battery was the unit extracted at Elouges by the 9th Lancers).

German machine guns were seen to be brought up to the Cambrai road, and they and the accompanying infantry were subjected to a withering fire by the 2 battalions in the line with support from the artillery, effectively preventing any German attack from developing.

At 3pm the 15th Brigade received the order to retreat. The 119th Battery fell back first, followed by the Bedfords, Dorsets and 121st Battery. The German infantry was held behind the Cambrai road by rifle fire from the Northumberland Fusiliers of 9th Brigade, the next battalion in the line to the west.

German artillery, guided by aircraft spotters dropping smoke flares, laid down a heavy barrage around Troisvilles, hitting the Fusiliers to the west of Troisvilles, the KOSB to the east and then, as they withdrew, the south-east of Troisvilles, and on the 15th Brigade battalions retreating through the town onto the Reumont road.

The bombardment forced the infantry to march in the fields parallel to the Reumont road, and, in the case of the Bedfords and Dorsets, to break into small groups to get through the barrage.

These battalions joined the Roman Road at Reumont or Maurois, and began the retreat to the south-west.

The 9th Brigade, positioned to the west of Troisvilles, had not been engaged, other than the Northumberland Fusiliers company firing on the German infantry threatening the 15th Brigade from behind the Cambrai road. That is other than the batteries of XXIII Brigade RFA, which had been firing with considerable effect on the distant German infantry.

Brigadier-General Shaw, the commander of 9th Brigade, saw the troops on his right retreating through Troisvilles, and was relieved to receive his own orders to retreat at around 3.30pm.

Covered by the 4th Royal Fusiliers, Shaw withdrew his battalions; 1st Northumberland Fusiliers, 1st RSF and 1st Lincolnshire, covered by gunfire from 107th and 108th Batteries RFA. 2 sections of these batteries were forced to abandon their guns, leaving 4 guns to the enemy.

Otherwise the 9th Brigade pulled out in good order, and took position to the west of Bertry, to cover the retreat of the rest of the 3rd Division. Casualties of the brigade were around 180 men and the ease of the withdrawal enabled the brigade to bring out its wounded.

To the west of the 9th Infantry Brigade, the German attack eased off from around midday. The opportunity was taken to bring up part of the 2nd Royal Irish Rifles, to re-enforce the 7th and 8th Brigades in and around Caudry.

Brigadier-General McCracken CB, DSO, commander of 7th Infantry Brigade, wounded during the Battle of Le Cateau on 26th August 1914 in the First World War

Just before 2pm the German artillery opened a heavy bombardment on Caudry, and an infantry attack was delivered to the east of Caudry, against the Gordon Highlanders and the Royal Scots.

This infantry attack was repelled, but in Caudry, Brigadier McCracken, commanding 7th Brigade, and his brigade major were seriously wounded. This was followed by an evacuation of the town by the brigade, in the belief that this had been ordered by McCracken before his incapacitation. This caused the premature loss of an important component in the western part of the II Corps line.

Simultaneously, a heavy attack was launched by German infantry on the Inniskilling Fusiliers, on the western side of Esnes, itself at the western end of the British infantry line. Although this attack was also repelled it was clear that the Germans were about to work their way around the British western flank in corps strength.

Shortly before 3pm, the 3rd Worcesters launched a counter-attack to recover Caudry that was partially successful. It was becoming clear that it was time for the 3rd and 4th Divisions to ‘go’.

The 4th Division established a rearguard before Ligny, hitherto the divisional reserve and headquarters area, comprising 1st Rifle Brigade and some Lancashire Fusiliers, with 135th Battery dug in for support. With this cover the 11th Brigade fell back into Ligny.

The German infantry pressed forward in close pursuit and attacked the British in and around Ligny. The Germans were repelled several times by devastating rifle, machine gun and artillery fire, until finally they abandoned their assaults around 5pm, leaving the 4th Division to continue its retreat.

The Gordon Highlanders east of Caudry:

The commanding officer of the 2nd Royal Irish Rifles was instructed to take command of the leaderless 7th Brigade in Caudry, and withdraw it, which he did by about 4.30pm.

On the right of the 7th Brigade, the retreat order was sent to the 8th Brigade at about 3.30pm. The order reached the 4th Middlesex and most of the 2nd Royal Scots, which immediately withdrew from the line.

The order did not reach the 1st Gordon Highlanders or the other units in positions with them in advance of the village of Audencourt; some of the Royal Scots, and 2 companies of the 2nd Royal Irish Regiment. These troops remained in the line, resisting the German attack.

A heavy German bombardment on Audencourt destroyed much of the 8th Brigade transport, increasing the confusion.

At 5pm, the Germans launched a heavy infantry attack on the remaining 8th Brigade positions in advance of Audencourt. The Gordons, Royal Scots and Royal Irish held the Germans back and inflicted heavy loss on them, the attack continuing for an hour.

The remnant of the 8th Brigade marched away to the south. The 7th Brigade left Caudry and marched south at 5pm. The Gordons and their accompanying units were left to dispute the field with the Germans, who were advancing in overwhelming numbers.

Retrieving the guns:

Withdrawal from contact with the German infantry and guns was difficult enough for the British infantry. For the gun batteries it was exceedingly dangerous. Many of the gun positions were in open fields. The horse teams had to be brought up, and the guns hitched on, in full sight of the German guns, machine guns and riflemen.

13 pounder gun of the Royal Horse Artillery with limber and crew, ready for action: Battle of Le Cateau on 26th August 1914 in the First World War

Many of the guns were only extracted from the firing line due to the exceptional bravery of the officers, gunners and drivers of the field and horse artillery. Of the guns supporting the Suffolks and the KOYLI on the right flank of the 5th Division, the teams of the 11th Battery galloped up to the guns and got 5 of them away, the sixth team being shot down before they could move the gun. The teams of the 80th and 37th Batteries got most of their guns away. The guns of the 52nd Battery had to be abandoned, as the teams were used for the other batteries. The gunners of the 52nd Battery were ordered to leave their guns, but one gun crew ignored this order and remained firing in support of the infantry.

At around 1.20pm an attempt was made to take the guns of 122nd Battery out of action, from its position behind the KOYLI. The teams galloped up, to the cheers of the infantry, but were subject to a storm of gun, machine gun and rifle fire. 2 guns were extracted, but the remaining teams and gunners were shot down, leaving 4 guns in the open, surrounded by dead and wounded artillerymen and horses.

The decision was made to disable the guns of 123rd and 124th Batteries, that were too exposed, and not to sacrifice the men and horses in attempts to extract them. Breech blocks were removed and the gun sights smashed, and the guns left in the field.

By the time the last of the 5th Division artillery was extracted, the German infantry were within 500 yards of the British line. The pressure was heavy, with German guns and machine guns sweeping the British positions.

Captain Reynolds RFA with Drivers Drain and Luke recovering one of the howitzers of 37th Battery during the closing phases of the Battle of Le Cateau on 26th August 1914. All three were awarded the Victoria Cross: Battle of Le Cateau on 26th August 1914 in the First World War

At this point, Captain Reynolds of the RFA advanced with 2 volunteer teams to try and extricate 2 of the abandoned howitzers of his 37th Howitzer Battery. The howitzers were hooked on and ready to go, when one of the teams was shot down, leaving the other to escape with its gun. Captain Reynolds and Drivers Luke and Drain were awarded the Victoria Cross for their actions in retrieving this howitzer. Other officers and soldiers received lesser gallantry awards.

The end of the Battle of Le Cateau:

By 5pm, II Corps and the 4th Division were disengaged from the firing line and retreating, with only some rearguards and those units that had not received the retreat order still in contact with the German forces.

The German IV Reserve Corps was advancing on the line between Beauvoir and Wambaix to carry out the outflanking movement to the west.

General Sordet’s French Cavalry Corps was in position beyond the British left flank, with his guns and cycle battalions attacking the western flank of the German IV Corps.

On the right flank of II Corps, the British retreat down the Roman Road from Le Cateau to St Quentin (the extension of the road from Bavai) was covered by various units; 1st Middlesex, 2nd Argylls, 2nd RWF, 1st Scottish Rifles (all from 19th Brigade) and 59th Field Company RE, positioned on a spur jutting into the river valley immediately to the north-east of Reumont.

These units engaged the substantial German forces now advancing down the Selle river valley, south-west from Le Cateau, and held them at bay.

Further to the south-west, at Maurois, were the DCLI and East Surreys, supported by a gun from 108th Heavy Battery.

At Escaufort were the Queen’s Bays (2nd Dragoon Guards) with E and L Batteries RHA from the Cavalry Division.

The 19th Brigade units pulled back through Reumont to Maurois, leaving a company of Norfolks in Reumont to contest the German advance, supported by 2 guns of 122nd Battery.

The German infantry advanced down the river valley, to a point on the flank of the Norfolks and halted. It seems that the 2 battalions of German infantry from the 7th Division were ordered to halt, to permit troops from the German III Corps to take over the pursuit of the British. However, this corps was far in the rear and did not come up until around midnight, leaving the British free to continue the retreat without this threat of envelopment being pressed.

As the main body of the British 5th Division moved on down the Roman Road, the rearguard units joined the road and moved south-west to further positions.

Instead of a vigorous pursuit by German infantry, the only parties that followed the retreating British were small patrols of cavalry, which presented little threat.

The British 3rd Division withdrew on Montigny, the 9th Brigade acting as rearguard. There was no German pursuit. The German focus was on the men from the Gordon Highlanders, the company of the Royal Scots and the 2 companies of the Royal Irish, which had not received the retreat order and were fighting on, in their positions to the east of Caudry.

Again, the Germans appear not to have appreciated that the main British force had gone. At about 8.30pm a heavy bombardment was opened on Audencourt, which the main body of the 3rd Division had left some hours before.

The retreat of the 4th Division at the Battle of Le Cateau:

The 4th Division received its order to retreat at about 5pm. By that time the German bombardment was heavy and increasing. German Jägers were infiltrating around the left flank of the division, forcing the Inniskilling Fusiliers back into Esnes.

The 10th Brigade, positioned around Haucourt, was designated the divisional rearguard. The 4th Cavalry Brigade provided additional support for the division’s disengagement from the Germans. Dispositions were arranged for the divisional artillery, to ensure support for the retreating infantry and the other gun batteries.

During the resistance to the German surprise attack, some of the battalions in the 11th and 12th Brigades had broken up into smaller groupings, which were extracted by their officers. Several of these groups had to work their way through the area, finding routes that were not blocked by German infantry.

The German guns fired on those parties of British troops that they saw, and continued to bombard their original and now evacuated positions. Other than this, there was little organised pursuit of the 4th Division, as it fell back and began its retreat.

Private Nathaniel Hartley, 2nd Lancashire Fusiliers, killed at Le Cateau on 26th August 1914 in the First World War

The final resistance at the Battle of Le Cateau:

As the various formations comprising the left wing of the BEF; The Cavalry Division, 4th Division and II Corps, began their retreat towards St Quentin, the units that had not received the retreat order fought on; the principal groups being the 2 companies of the KOYLI on the right flank of the 5th Division positions, and the Gordons, Royal Scots and Royal Irish of 3rd Division to the east of Caudry. There were other smaller groups.

The Gordons group eventually evacuated their positions before Audencourt and attempted to evade the Germans and re-join the main army, but were finally overrun in bitter fighting near Clary. 500 Gordon Highlanders became casualties in the battle. A few Gordons escaped, and found their way through the German lines to Amsterdam.

In the 4th Division area, companies from the King’s Own and the Dublin Fusiliers continued to contest the German advance, not having received the retreat order, before eventually attempting to withdraw.

The Dublin Fusiliers reached Clary, gathering men from every division in II Corps. Finding their way blocked by German formations, the party turned north. Eventually 78 officers and men reached Boulogne, the remainder having been captured or become casualties.

It is the view of the official war historian, Brigadier Edmonds, that the determined resistance of these groups enabled the British left wing to begin its retreat without significant German interference, the German efforts being concentrated on overcoming these groups.

Along the abandoned British line, the Germans maintained artillery bombardments during the evening of 26th August, well after the British troops had pulled back, indicating that the Germans failed to appreciate that a general British retreat was under way.

Casualties at the Battle of Le Cateau:

British losses in the fighting on 26th August 1914 were 8,482 men (12% of the force engaged) and 38 guns.

German losses were not declared, but were probably in excess of 15,000 men.

Dead horses and men around an 18 pounder British field gun: Battle of Le Cateau on 26th August 1914 in the First World War

Aftermath to the Battle of Le Cateau:

The BEF continued its retreat towards St Quentin, which is dealt with in the next section.

Lance Corporal Frederick Holmes, mounting the lead horse of the abandoned gun team, before riding the team back and winning the VC: Battle of Le Cateau on 26th August 1914 in the First World War

Lance Corporal Frederick Holmes VC, 2nd KOYLI: Battle of Le Cateau on 26th August 1914 in the First World War

Decorations following the Battle of Le Cateau:

5 Victoria Crosses were awarded for actions during the Battle of Le Cateau; to Major Yate and Lance Corporal Holmes of 2nd King’s Own Yorkshire Light Infantry and to Captain Reynolds and Drivers Luke and Drain of 37th Howitzer Battery RFA.

The 1914 Star was issued to all ranks who served in France or Belgium between 5th August 1914, the date of Britain’s declaration of war against Germany and Austria-Hungary, and midnight on 22nd/23rd November 1914, the end of the First Battle of Ypres. The medal was known as the ‘Mons Star’. A bar was issued to all ranks who served under fire stating ‘5 Aug. to 23 Nov. 1914’.

An alternative medal the 1914/1915 Star was issued to those not eligible for the 1914 Star.

The 1914 Star with the British War Medal and the Victory Medal were known as ‘Pip, Squeak and Wilfred’. The British War Medal and the Victory Medal alone were known as ‘Mutt and Jeff’.

Anecdotes and traditions from the Battle of Le Cateau:

- Major C.A.L. Yate commanded one of the companies of 2nd King’s Own Yorkshire Light Infantry and was in command of the 2 companies in the forward positions. Yate failed to receive the order to retreat and continued to resist the German attack. Finally, Yate was left with 19 uninjured men. He led them in a desperate charge against the German infantry. All 19 became casualties or prisoners. Yate was wounded and captured. Yate was held at the Torgau Officers’ Prisoner of War Camp, from which he made several escape attempts. Yate escaped for the last time, and it is believed that when challenged by German civilians, he cut his own throat with a razor. Major Yate was awarded a posthumous Victoria Cross for his conduct at Le Cateau. Major Yate was an experienced soldier, having fought on the North-West Frontier of India, and in the South African War, in which he was wounded. Yate was a highly competent linguist, holding the Interpreter Qualification for French and German and other languages. In 1904, Yate was attached to the Japanese Army during the Russo-Japanese War. He was awarded 2 decorations by the Japanese Emperor. Yate seems to have adopted the Japanese belief that a soldier should never be captured. This may explain his suicide. On the other hand, it is reported that Yate was interviewed at the prisoner of war camp by 2 officers from the German security services, following which he was highly agitated and pressed his need to escape. Although this is not reported in any of the accounts relating to Yate, it may be that he was employed on clandestine work in Germany before the War, using his fluency in German, and that he feared that he might be tried and shot for those activities as a spy. His VC is in the KOYLI rooms in the Doncaster Museum.

- The second Victoria Cross for 2nd KOYLI at Le Cateau was won by Lance Corporal Frederick Holmes. Corporal Holmes, on leaving the forward position, picked up a wounded bugler and carried him some 2 miles before handing him to stretcher bearers. He then returned to the front line, where he encountered a stationery gun team with the 18 pounder gun hitched on, but all the drivers and gunners dead or wounded. He placed a wounded trumpeter on one of the horses and mounted the lead horse himself. He urged the horses into motion, and then galloped, apparently out of control, for some miles, using his bayonet on German soldiers who tried to stop him. It was the next day that he encountered an artillery column, when he handed over his gun.

- Major Tom Bridges, who served in France with 4th Dragoon Guards from the opening shots on 22nd August 1914, wrote of Le Cateau in his book ‘Alarms and Excursions’, ‘The II Corps managed to escape the German clutches but the damage to its moral was great and in some cases lasting.’

References for the Battle of Le Cateau:

Mons, The Retreat to Victory by John Terraine.

The First Seven Divisions by Lord Ernest Hamilton.

The Official History of the Great War by Brigadier Edmonds August-October 1914.

The previous battle in the First World War is the Battle of Landrecies

The next battle in the First World War is the Battle of Le Grand Fayt