The successful defence of Jellalabad in 1841 to 1842 that went a little way to restore the British reputation devastated by the Battles of Kabul and Gandamak

‘Remnants of an Army’: Dr Brydon arriving at Jellalabad on 13th January 1842, last survivor of the Anglo-Indian Army in the retreat from Kabul: Siege of Jellalabad from 12th November 1841 to 13th April 1842 during the First Afghan War: picture by Lady Butler

The previous battle of the First Afghan War is the Battle of Kabul and the Retreat to Gandamak

The next battle of the First Afghan War is the Battle of Kabul 1842

Brigadier Sir Robert Sale: Siege of Jellalabad from 12th November 1841 to 13th April 1842 during the First Afghan War: picture by George Clint

Battle: Siege of Jellalabad

War: First Afghan War

Date of the Siege of Jellalabad: 12th November 1841 to 13th April 1842

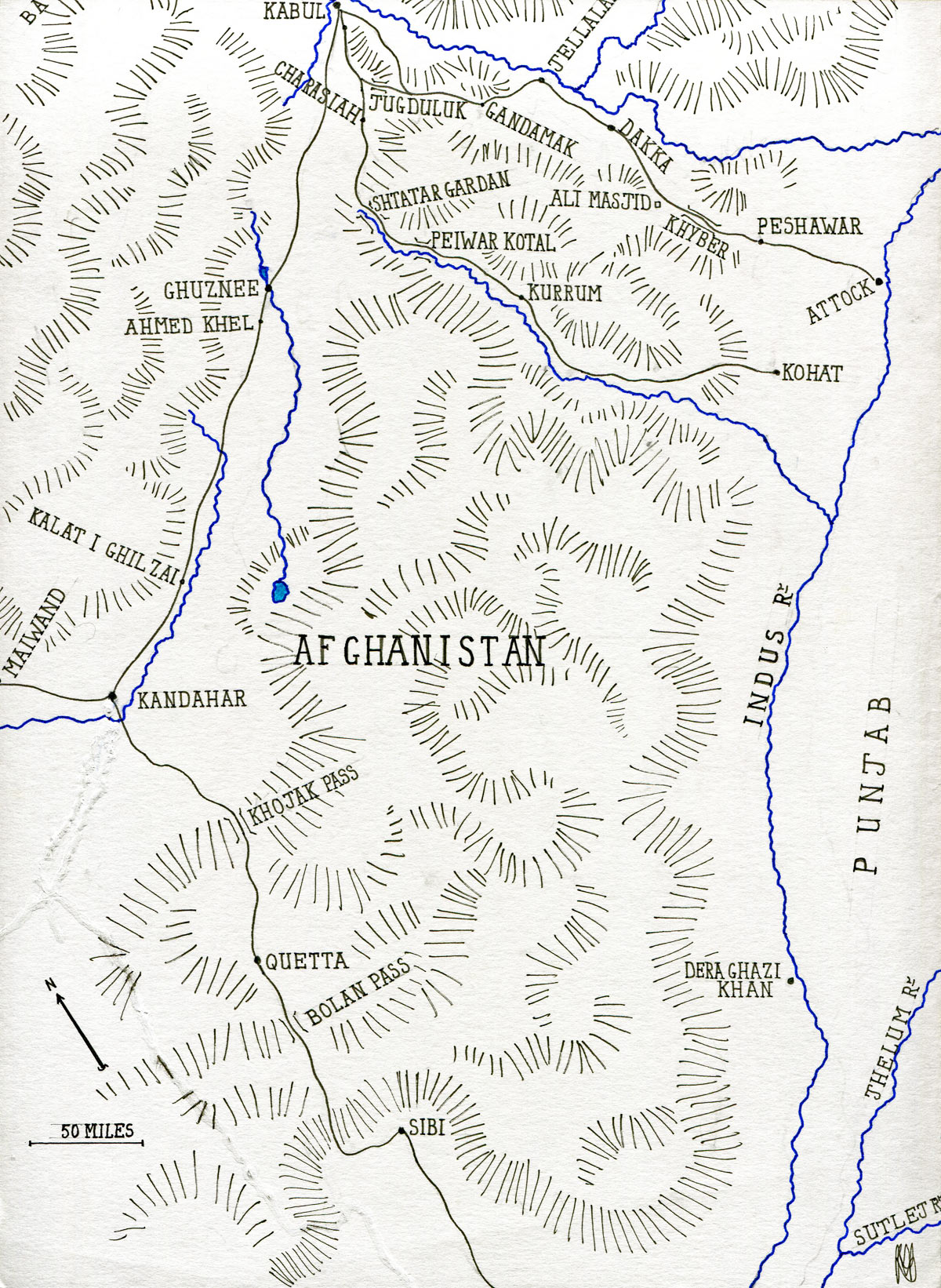

Place of the Siege of Jellalabad: North Eastern Afghanistan

Combatants at the Siege of Jellalabad: British and Indian troops of the Bengal Army and soldiers of the army of Shah Shuja against Afghans and Ghilzai tribesmen.

Commanders at the Siege of Jellalabad: Brigadier Sir Robert Sale commanded the Jellalabad garrison against Ameer Akbar Khan

Size of the armies at the Siege of Jellalabad: 1,500 British and Indian troops against 5,000 Afghans.

HM Regiment of Foot: Siege of Jellalabad from 12th November 1841 to 13th April 1842 during the First Afghan War

Uniforms, arms and equipment at the Siege of Jellalabad:

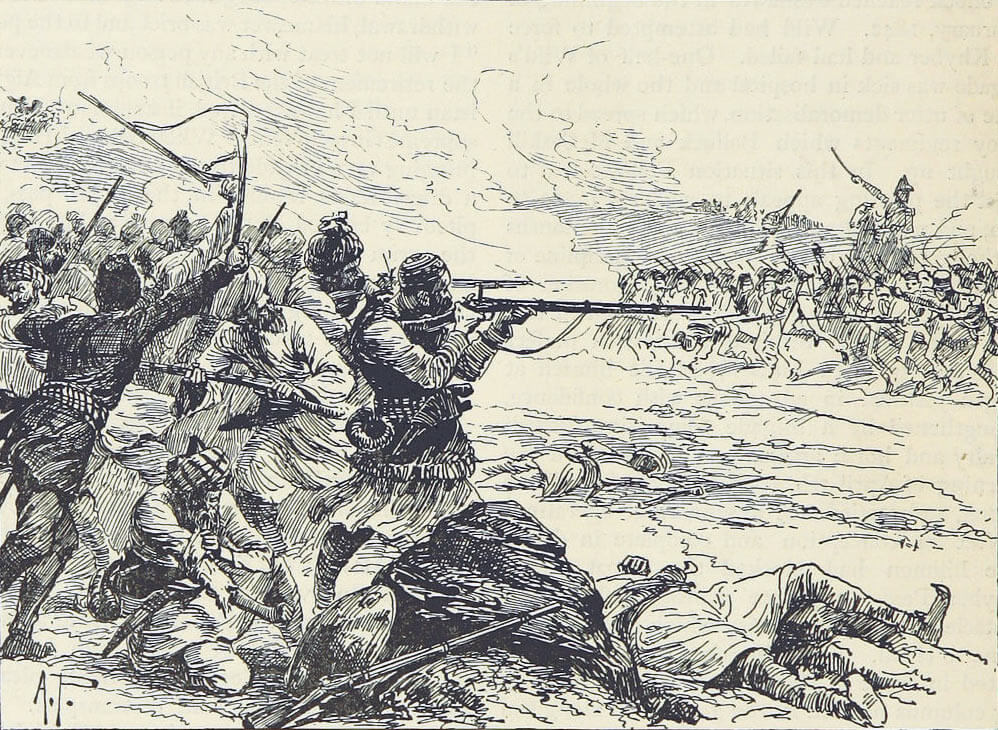

The British infantry, wearing cut away red jackets, white trousers and shako hats, were armed with the old Brown Bess musket and bayonet. The Indian infantry were similarly armed and uniformed.

The Afghans and Ghilzai tribesmen carried swords and jezails, long barrelled muskets.

Winner of the Siege of Jellalabad: The British and Indian Army under Brigadier Sir Robert Sale.

British and Indian Regiments at the Siege of Jellalabad:

HM 13th Foot.

35th Bengal Native Infantry (BNI).

1 Squadron of Skinner’s Horse.

Shah Shujah’s Sappers.

Artillery.

The First Afghan War:

The British colonies in India in the early 19th Century were held by the Honourable East India Company, a powerful trading corporation based in London, answerable to its shareholders and to the British Parliament.

Skinner’s Horse at exercise: Siege of Jellalabad from 12th November 1841 to 13th April 1842 during the First Afghan War

In the first half of the 19th century, France as the British bogeyman gave way to Russia, leading finally to the Crimean War in 1854. In 1839 the obsession in British India was that the Russians, extending the Tsar’s empire east into Asia, would invade India through Afghanistan.

This widely held obsession led Lord Auckland, the British Governor-General in India, to enter into the First Afghan War, one of Britain’s most ill-advised and disastrous wars.

Until the First Afghan War, the Sirkar (the Indian colloquial name for the East India Company) had an overwhelming reputation for efficiency and good luck. The British were considered to be unconquerable and omnipotent. The Afghan War severely undermined this view. The retreat from Kabul in January 1842, and the annihilation of Elphinstone’s Kabul garrison dealt a mortal blow to British prestige in the East only rivalled by the fall of Singapore 100 years later.

The causes of the disaster are easily stated: the difficulties of campaigning in Afghanistan’s inhospitable mountainous terrain, with its extremes of weather, the turbulent politics of the country and its armed and refractory population, and, finally, the failure of the British authorities to appoint senior officers capable of conducting the campaign competently and decisively.

Jellalabad seen from the north by the Kabul River: Siege of Jellalabad from 12th November 1841 to 13th April 1842 during the First Afghan War

The substantially Hindu East India Company army crossed the Indus with trepidation, fearing to lose caste by leaving Hindustan and appalled by the country they were entering. The troops died of heat, disease and lack of supplies on the desolate route to Kandahar, subject, in the mountain passes, to repeated attack by the Afghan tribes. Once in Kabul, the army was reduced to a perilously small force and left in the command of incompetents. As Sita Ram in his memoirs (‘Sepoy to Subedar’) complained: ‘If only the army had been commanded by the memsahibs all might have been well.’

The disaster of the First Afghan War was a substantial contributing factor to the outbreak of the Great Mutiny in the Bengal Army in 1857.

The successful defence of Jellalabad, and the progress of the Army of Retribution in 1842, could do only a little to rebuild the East India Company’s diminished reputation.

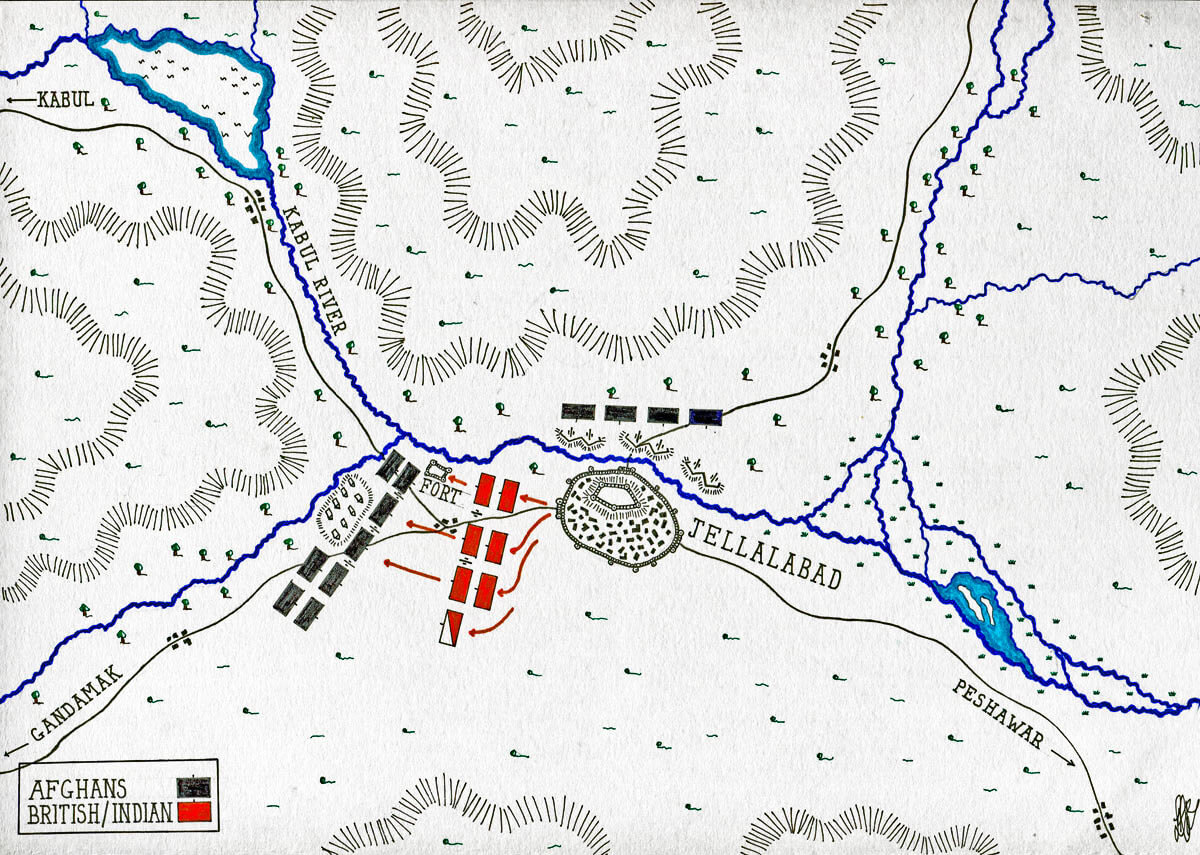

Map of the Siege of Jellalabad from 12th November 1841 to 13th April 1842 during the First Afghan War: map by John Fawkes

Account of the Siege of Jellalabad:

Brigadier Sir Robert Sale’s brigade, retreating from Kabul under constant attack by the Ghilzai tribesmen, and, ignoring a frantic order from the British commander, General Elphinstone, to return to Kabul, reached the Afghan town of Jellalabad on 12th November 1841.

Soldiers of the 13th Foot and 35th Bengal Native Infantry in Jellalabad: Siege of Jellalabad from 12th November 1841 to 13th April 1842 during the First Afghan War

Jellalabad’s defences were in a ruinous state, but the indefatigable Captain George Broadfoot set his sappers to work rebuilding them. The Afghans, following the British and Indian troops to Jellalabad, harried the sappers with a constant fire, particularly from a neighbouring hill, where they were inspired by a Ghilzai bagpiper, until driven away by a sortie on 15th November 1841.

The Afghans surrounded the town, but were pushed back by another determined sortie, led by Colonel Dennie of the 35th BNI, on 1st December 1841.

As the siege of Jellalabad by the Afghans got under way, communications reached Jellalabad from Kabul, charting the desperate straits of the British and Indian garrison in the Afghan capital.

On 12th January 1842, the news arrived that the garrison had abandoned Kabul and was marching the hazardous route through the mountains to Jellalabad.

Afghan Band: Siege of Jellalabad from 12th November 1841 to 13th April 1842 during the First Afghan War

On 13th January 1842, the sole survivor of the Kabul army, Dr Brydon, extensively wounded and in a state of collapse, reached Jellalabad. The garrison stood to its posts in the expectation of an immediate attack by the pursuing Afghans, which did not materialise.

Almost simultaneously, news arrived from India that the force under General Wilde, lying at the base of the Khyber Pass, could not begin its advance, so the Jellalabad garrison could expect no early relief.

Following this dismal news from the east, a series of communications arrived from Shah Shuja, the puppet Ameer in Kabul, demanding that the Jellalabad brigade abandon the town to an Afghan governor and withdraw to India.

Brigade Sir Robert Sale held a council of war with the senior officers of his regiments. Brigadier Sale and his chief of staff, Major Macgregor, were for abandoning Jellalabad and retreating east to India. Captain Broadfoot, Captain Oldfield of the artillery and Captain Henry Havelock urged that the town must be held.

Jellalabad gate and defences before the earthquake: Siege of Jellalabad from 12th November 1841 to 13th April 1842 during the First Afghan War

On 12th February 1842, a further demand that the town be given up arrived from Kabul, but by this time the senior officers had recovered their composure. The demand was rejected and the officers resolved to hold Jellalabad to the end. They were reinforced in their resolve by the arrival of a message from General Pollock, the new commander of the relieving army in India, announcing that he would advance at the first opportunity.

During the period of correspondence with Shah Shujah, Broadfoot and his sappers worked untiringly to strengthen the fortifications.

Jellalabad gate and defences after the earthquake: Siege of Jellalabad from 12th November 1841 to 13th April 1842 during the First Afghan War

On 19th February 1842, an earthquake destroyed much of their efforts, but Broadfoot’s leadership was inspirational, and the garrison quickly restored the broken works.

The Afghans, now commanded by Akbar Khan, invested the town closely.

On 11th March 1842, Colonel Dennie led out a further sortie and captured some 500 Afghan sheep left to graze under the town walls, a welcome addition to the commissariat stores.

HM 13th Regiment and Skinner’s Horse capturing the flock of sheep: Siege of Jellalabad from 12th November 1841 to 13th April 1842 during the First Afghan War: picture by Daniel Cunliffe

On 9th April 1842, the Afghans fired a series of salutes. Coupled with disturbing messages from the east, the salutes led the commanders of the garrison to believe that General Pollock had been driven back.

Brigadier Sale resolved on a major sortie by the entire garrison, in an attempt to drive the Afghan besiegers away. The odds were not in the garrison’s favour. Akbar had some 5,000 to 6,000 men. The garrison numbered around 1,500 men.

At dawn on 7th April 1842 three columns issued from the Kabul Gate into the open country outside Jellalabad. The columns advanced in line towards Akbar’s camp, some 3 miles away, its right flank resting on the river.

Half way to the camp lay a ruined fort, held by Afghans. Colonel Dennie allowed his column to be diverted into the fort, where a vicious hand to hand fight accounted for several British and Indian casualties including Dennie himself.

Sortie from Jellalabad: Siege of Jellalabad from 12th November 1841 to 13th April 1842 during the First Afghan War

Dennie’s troops finally conformed to the other two columns, commanded by Havelock and Monteath of the 13th, and the advance continued. The artillery came up in support and a heavy fire was opened on the Afghans, as the three columns advanced into Akbar’s camp capturing his artillery and driving his soldiers away in rout.

Jellalabad Badge of the 13th Prince Albert’s Own Light Infantry: Siege of Jellalabad from 12th November 1841 to 13th April 1842 during the First Afghan War

By 7am on 8th April 1842 the Afghan besieging force had fled and the 35th BNI, 13th Foot and the artillery were enabled to march back into Jellalabad in triumph. The garrison had raised the siege without assistance.

On 13th April 1842 Pollock’s Army of Retribution arrived, to be played into Jellalabad by the band of the 13th with the Scottish song “Oh but you’ve been a lang time acoming.”

Casualties at the Siege of Jellalabad:

The British and Indian garrison suffered casualties of 20 men killed and wounded during the siege, and 42 men killed and wounded during the final sortie, including Colonel Dennie. Afghan casualties are unknown.

Follow-up to the Siege of Jellalabad:

The holding of Jellalabad was an enormous boost to the British in India, and to Britain, after the disasters of Kabul and Gandamak. Pollock left Jellalabad for Kabul, to punish the Afghans for having the temerity to defend their country.

Jellalbad medal issued by the East India Company for the Siege of Jellalabad from 12th November 1841 to 13th April 1842 during the First Afghan War

Anecdotes and traditions from the Siege of Jellalabad:

- The defence of Jellalabad made heroes of the 13th It is reported that as the regiment marched back through India, to return to Britain, every garrison fired a ten-gun salute in its honour. Queen Victoria directed that the regiment be made Light Infantry, carry the additional title of ‘Prince Albert’s Own’ and wear a badge depicting the walls of the town with the word ‘Jellalabad’ inscribed.

- The East Indian Company issued a medal to commemorate the siege and issued it to every member of the Jellalabad garrison present in Jellalabad during the period 12 November 1841 to 16 April 1842.

- Captain Henry Havelock of the 13th Regiment greatly distinguished himself in the Indian Mutiny, relieving the British Residency in Lucknow and dying there of dysentery in 1857. Havelock studied military history and theory in great depth. He was a driven Christian and established Bible reading classes for all ranks in his regiment. The crisis generated by the inadequate elderly British generals needed officers of the ability and driven determination of Havelock and Broadfoot to ensure the survival of the Anglo-Indian garrison in Jellalabad.

References for the Siege of Jellalabad:

Afghanistan From Darius to Amanullah by Lieutenant General Sir George McMunn.

The Afghan Wars by Archibald Forbes.

History of the British Army by Fortescue.

The previous battle of the First Afghan War is the Battle of Kabul and the Retreat to Gandamak

The next battle of the First Afghan War is the Battle of Kabul 1842