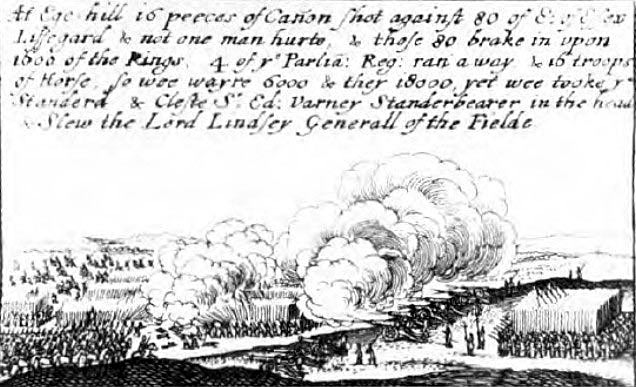

The First Major Battle of the English Civil War, fought on 23rdOctober 1642

Cavalry action: Battle of Edgehill 23rd October 1642 in the English Civil War: picture by Palamedes Palamedesz

The previous battle in the British Battles series is the Spanish Armada

The next battle in the English Civil War is the Battle of Seacroft Moor

To the English Civil War index

Battle: Edgehill

War: English Civil War.

Date: 23rd October 1642.

Place of the Battle of Edgehill: At Kineton, near Banbury, in Oxfordshire.

Combatants at the Battle of Edgehill: The forces of King Charles I against the forces of the English Parliament.

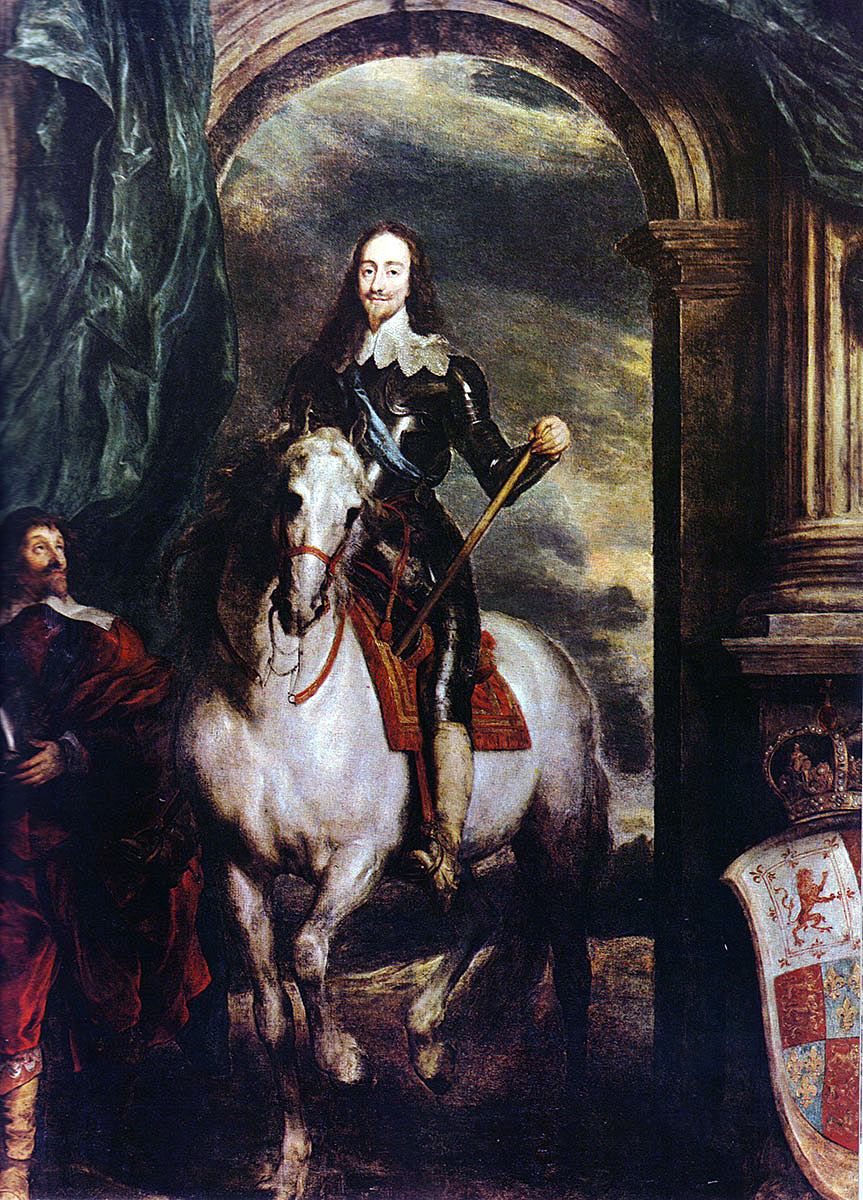

King Charles I of England: picture by Sir Anthony van Dyck: Battle of Edgehill on 23rd October 1642 in the English Civil War

Generals at the Battle of Edgehill: King Charles I was the commander of his Royal forces. His Lord General was the Earl of Lindsey at the outset of the battle. A dispute with Prince Rupert caused Lindsey to give up his appointment and fight at the head of his regiment, where he was mortally wounded during the battle. Prince Rupert under his commission as ‘General of the Horse’ was entitled to act free from supervision by any other officer.

The Parliamentary forces at Edgehill were commanded by the Earl of Essex.

Size of the armies at the Battle of Edgehill: The Royalist army comprised around 14,000 men, of which probably 3,000 were Horse, and 20 guns. The Parliamentary army was around 15,000, but a significant part of the army was in quarters too far from the field to arrive in time to fight in the battle. Essex had around 4,000 Horse and some 40 cannon.

Winner of the Battle of Edgehill: Clarendon makes it clear that the contemporary view, whether justified or not, was that Edgehill was a Royalist victory. The Royalist cavalry on each wing drove the Parliamentary cavalry opposing them off the field, while the Parliamentary Infantry pushed the Royalist Infantry back. Both sides initially remained on the field.

Uniforms, arms and equipment at the Battle of Edgehill:

When the Civil War broke out in 1642, England was without a regular military establishment and had little recent war-making experience. Each side, Royalist and the Parliamentarian, was forced to build up its armies from scratch, relying upon the regional system of ‘Trained Bands’ or militia.

The Trained Bands varied widely in quality, but were generally only suitable as a starting point. Many of these regional forces were not prepared to leave their counties, and probably only the London Trained Bands were ready and capable of sustained military action, fighting for the Parliament.

The one military resource, that was important to each side, was the pool of English and Scottish officers with experience of fighting in Europe, where the Thirty Years War (1618 to 1648) was in progress across the continent. Each side relied upon these officers, particularly in the use of artillery and in military engineering.

The Civil War came squarely in the transition from Medieval reliance on the shock of armoured horsemen, bows, swords and lances, to the use of firearms, both hand held and artillery.

In the late 15th Century, the Swiss briefly dominated the European battlefield with massed pikemen. The Swiss dominance was broken by the tactical use of firearms on the battlefield. Both infantry and cavalry turned from shock tactics to the use of firearms; pistols for the horsemen and arquebuses for the infantry. Cannon became increasingly mobile and available for use in battle, as opposed to being mainly a siege weapon.

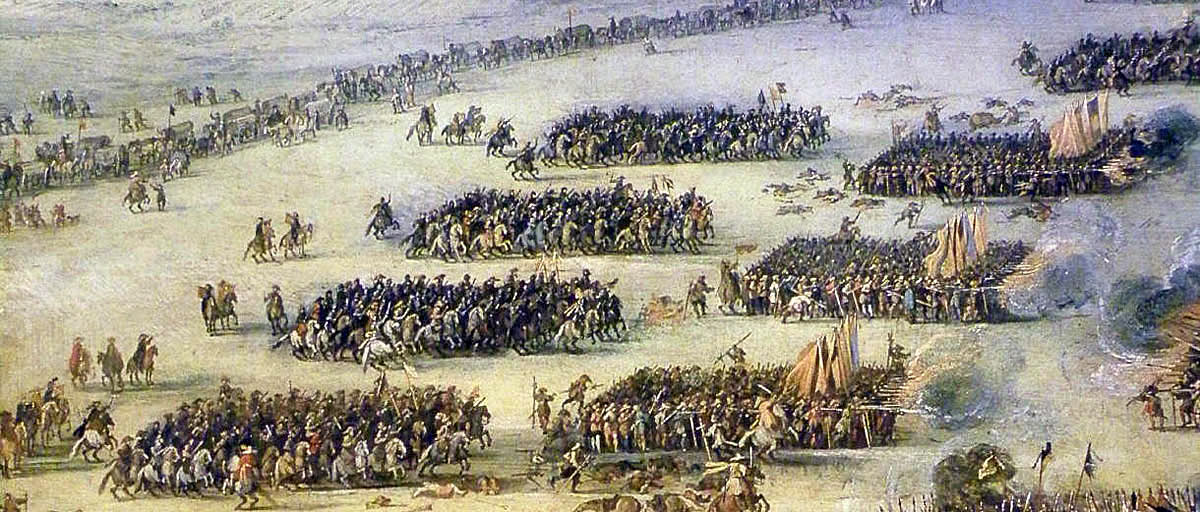

Pikemen at the Battle of Rocroi in France, in 1643: picture by Sebastian Vrancx. This might well have been a picture of the Battle of Edgehill, fought in the previous year on 23rd October 1642 in the English Civil War

The Thirty Years War produced a number of important commanders; Wallenstein for the Imperialists, Prince Maurice of Nassau in the Netherlands and, pre-eminently, King Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden.

English and Scottish soldiers, largely Protestant, fought mainly for the two Protestant leaders, Prince Maurice and Gustavus Adolphus.

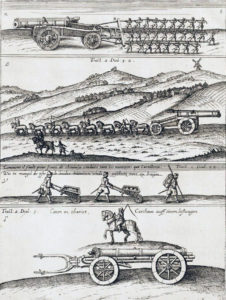

Siege artillery of the mid 17th Century: Battle of Edgehill 23rd October 1642 in the English Civil War

These two Protestant soldiers devised differing systems of battle, which produced conflicting schools of tactics in the English Civil War on each side. This conflict showed itself immediately at Edgehill, where the Earl of Lindsey resigned his appointment as Royalist commander following a dispute over which system to adopt.

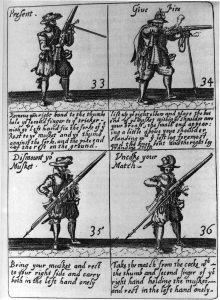

Prince Maurice applied the older system of tactics, which relied heavily on the use of firearms as against shock. Cavalry approached their target at a slow speed, and discharged their pistols in a rolling sequence of ranks, before engaging in mêlée. The infantry used a similar system, forming 15 or more ranks, with the musketeers discharging their pieces, before countermarching to the rear to reload, delivering a rolling fire at the enemy. Each infantry formation contained a force of pikemen, which would keep the enemy at bay with their 16 foot pointed weapons, or use them as offensive weapons in an advance.

Gustavus Adolphus, on the other hand, put his tactical emphasis on massed fire and shock action. Infantry musketeers formed as few as 3 to 6 ranks, closing up to deliver a single volley before the assault. Swedish cavalry delivered their attack by way of a charge, and were prohibited from firing pistols, other than in the mêlée that followed . Cavalry charges were conducted at speed, using the sword, thereby returning to the traditional role of the horseman in battle.

Royalist cavalry attacking at the Battle of Edgehill on 23rd October 1642 in the English Civil War: picture by Harry Payne

Small field guns were produced, light enough to move around the battlefield and provide immediate support to the other arms. Some guns were made of leather. The Swedes deployed groups of ‘Commanded Musketeers’, to provide fire support for the cavalry and other units.

The sedate use of firearms by other nationalities produced tactics that could be hesitant and indecisive, while the Swedes of Gustavus Adolphus were aggressive and decisive. The success of their tactics was shown resoundingly by the victorious battles of Breitenfeld (1631) and Lützen (1632).

English and Scottish officers played prominent roles in the armies of Prince Maurice and Gustavus Adolphus.

Cavalry and ‘commanded musketeers’ of the Period of the English Civil war: Battle of Edgehill on 23rd October 1642: picture by Peter Sneyers

In the cavalry, the fully armoured ‘cuirassier’ was, by 1642 a rarity on the battlefield, being expensive to equip and there being few horses strong enough to carry the weight of the man’s full armour. There were nevertheless some cuirassiers in the English Civil War.

Well-equipped regiments of horse wore breast and back plate armour and a helmet. Weapons were a sword, pistols and often some form of carbine firearm.

Artillery of the mid 17th Century on the move: Battle of Edgehill 23rd October 1642 in the English Civil War

Clarendon repeatedly complains that the Parliamentary cavalry (and infantry) were fully equipped while the Royalist cavalry were largely armed only with a sword and had little armoured protection.

In the mid-17th Century dragoons were still, in effect, mounted infantry, and not full cavalry, as they became in the following century. A dragoon was armed with a musket and a sword. In many Civil War actions, including Edgehill, dragoons were used on the flanks of the army to hold hedge lines on foot and act with the cavalry as mobile infantry.

Infantrymen carried either the pike, a 16 foot wooden shaft with an iron tip held in place by a socket long enough to avoid being cut off or a musket. Most regiments attempted to achieve a balance between the two forms of soldier, so as to provide firepower and hand to hand combat capability.

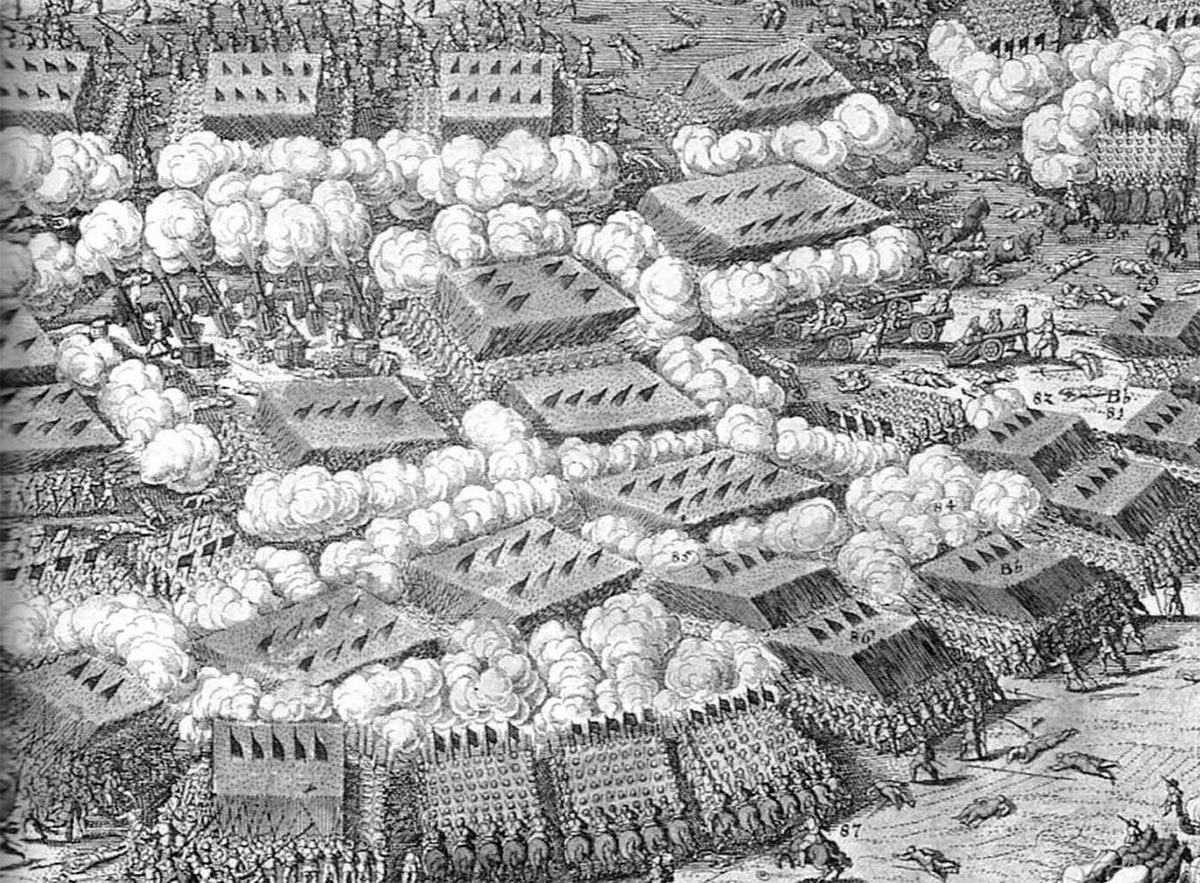

Contemporary representation of the Battle of Breitenfeld in 1632, showing the larger infantry formations of the Imperial army, left upper, against the smaller Swedish infantry formations, right lower; each comprising a central core of pikemen surrounded by musketeers. The tactics at the Battle of Edgehill on 23rd October 1642 in the English Civil War drew heavily on the systems used at Breitenfeld and other battles of the Thirty Years War

Hand held firearms were developing. The basic weapon was the firelock with a firing mechanism relying upon a burning match that the trigger brought down on the firing pan. Firing was difficult in bad weather as rain extinguished the match. There was a constant explosion hazard due to the proximity of gunpowder to the naked burning match. The match remained alight for a finite period, usually about 20 minutes and musketeers were frequently caught without a burning match with which to fire their weapons.

Musketeer of the English Civil War period armed with a Matchlock: Battle of Edgehill on 23rd October 1642 in the English Civil War

Artillery and infantry positioned open barrels of gunpowder immediately behind the line in battle to provide reserves of gunpowder. Time and again these open ‘budge barrels’ were ignited by musketeers’ matches with disastrous results.

The main forms of musket detonation available to replace the matchlock were the wheel lock and the firelock. Wheel locks were expensive and relied upon a spring mechanism that was easily damaged. The firelock or fusil, relying upon a spark ignited by a hammer striking a flint was the obvious replacement for the matchlock. It also was expensive and production was limited. Fusils were issued to infantry deputed to guard the cannon and therefore in contact with large amounts of gun powder.

The firelock musketeer when fully equipped carried 12 charges of powder held in wooden containers hung from a cross-belt, known as the ‘Twelve Apostles’. An infantry regiment when on the move made a distinctive sound, as thousands of wooden containers rattled together. This noise with the glow of hundreds of firelock matches made covert movement at night difficult.

The lack of military experience in the English establishment showed itself immediately in the Civil War. It took time to work out command structures and to devise tactics for use in battle. In the opening weeks neither side seemed to have a workable strategy. Both sides, once they had taken the field had difficulty discovering the whereabouts of the opposing army. Supply systems failed to provide for the troops in the field, it being necessary to distribute each army in billets over a wide area to ensure the troops were fed. Considerable time was wasted each day assembling the soldiers for the march or for battle.

Regiment of Foot of the period of the English Civil War comprising pikemen and musketeers: Battle of Edgehill 23rd October 1642: picture by Peter Sneyers

Campaigning began as soon as the armies were assembled, inhibiting pre-campaign training. While infantry could be trained in the field, this was notoriously difficult for cavalry. It was a military axiom that, during a campaign the infantry improves while the cavalry deteriorates, worn out by the burdens of the march and the reconnaissance duties imposed on horsemen.

As the horse was the main means of transport in England a large pool of experienced horsemen, many of whom hunted on horseback for recreation was available for the mounted regiments of each side. The problem was imposing on these individuals, many highly competitive, the discipline necessary to make the cavalry arm an asset rather than a liability, particularly as many officers were as devoid of discipline as the soldiers. Controlling cavalry in the excitement of battle is notoriously difficult and requires extensive training in non-operational circumstances. The Royalists never achieved this, while the Parliamentarians only really did so with the establishment of the New Model Army in 1645.

King Charles I, King of England: Battle of Edgehill 23rd October 1642 in the English Civil War: picture by Sir Anthony van Dyck

Background:

The causes of the Civil War are complex and dealt with in great detail in a number of books. The dispute between the Crown and Parliament began following the accession of the first Stewart to the throne, James I, in 1603. The character of Charles I, the son and successor to James I, acerbated all the latent problems. Charles I appeared to the majority of his subjects as a remote and difficult man, incapable of compromise on the issue of royal supremacy. Charles’ main problem was obtaining the money necessary to run the monarchy and the country, while avoiding the obligations that Parliament attempted to impose upon him, when providing the money. King Charles’s reign is a catalogue of disputes with the various Parliaments and members.

On 4th January 1642, King Charles entered Parliament, with a body of armed men, intending to arrest the five members who particularly aggravated him. The five were not present, having taken sanctuary in the City of London.

Attempted arrest of the 5 members of Parliament by King Charles I on 4th January 1642, the incident that prompted King Charles to leave London, and triggered the English Civil War: Battle of Edgehill 23rd October 1642

On 2nd March 1642, King Charles left London, considering that war was inevitable with Parliament, and that London was firmly in the Parliamentary camp. He travelled north, reaching York on 19th March 1642.

Over the next few months, there was a fruitless sequence of negotiations between King Charles and Parliament. During this time, each side assembled its forces. Parliament possessed a number of major advantages; London was firmly for Parliament, providing a major source of financial support, and the only Trained Bands in the country that could be relied upon; Parliament controlled all the main armouries, and also the navy, thereby inhibiting the Royalists in their efforts to obtain weapons, either domestically or from abroad. The only city in England considered to be wholeheartedly for the King was Oxford.

King Charles was handicapped by his lack of financial resources, from the commencement of the war. This made the raising of troops difficult, as they could not be paid, nor equipped, nor maintained. Every Royalist supporter, that could be contacted, was pressed for financial assistance to the Crown. Clarendon tells the wryly amusing tale of how the King sent Lord Capel to see the wealthy Earl of Kingston, and John Ashburnham, Groom of the Bedchamber, to see the equally well endowed Lord Deincourt, both with estates near Nottingham, to request a loan. Capel journeyed to see the Earl of Kingston, who said he regretted that he did not have the resources to comply with His Majesty’s request, but that he had a neighbour, who was extremely wealthy, and would definitely be able to assist – Lord Deincourt.

Meanwhile, Ashburnham was visiting Lord Deincourt. Deincourt was dismayed to have to tell Ashburnham that he was a poor man, without the means to provide the King with a loan …. However he knew a rich nobleman, living just up the road, who was more than able to assist His Majesty – the Earl of Kingston.

Clarendon points out the irony that Kingston was killed fighting for the King. He was prepared to die for him, but was not prepared to assist the King financially. Deincourt’s estates were later sequestered by Parliament, due to his Royalist sympathies, and he died in poverty.

It was Clarendon’s view, that the failure of many Royalist magnates to assist the King with their financial resources was a significant cause for the loss of the war.

However, in the summer of 1642, a group of Catholic gentry in Shropshire and Staffordshire combined to provide the King with an advance payment of their fines for being recusants (refusing to attend Church of England worship). A wealthy Shropshire squire, Sir Richard Newport, provided the King with £6,000 in exchange for being advanced to a barony.

Earl of Essex, the Parliamentary

commander at the Battle of Edgehill on 23rd October 1642 in the English Civil War

The universities of Oxford and Cambridge contributed their silver and gold plate to the Royalist cause, and subsequently made generous cash payments to King Charles. The Cambridge plate was intercepted by Cromwell on its way to the King on 10th August 1642.

These sums enabled the King to take the field in the summer of 1642, in an attempt to recover London.

On 12th June 1642, King Charles issued his Commission of Array, summoning his subjects to serve on his behalf. This was in effect the King’s declaration that he was recruiting an army

On 15th July 1642, Parliament appointed the Earl of Essex as its captain general, to command its field army.

On the same day, Queen Henrietta Maria, who had fled to the Netherlands, appointed Prince Rupert of the Rhine, as King Charles’s general of the horse. Prince Rupert, and his brother Prince Maurice, spent the rest of the month and much of August, in evading the naval ships of the Parliament, and sailing to Newcastle, from where they rode to join King Charles.

Prince Rupert, an important Royalist commander throughout the Civil War, was born on 17th December 1619, and was 22 years old in 1642, when he arrived in England to fight for his uncle, King Charles. Prince Rupert was 6 foot 4 inches in height, and the son of the Elector Palatine and Elizabeth, sister of King Charles. Prince Rupert saw service during the Thirty Years War on the Continent of Europe, before being captured by the Imperialists. The Emperor thought sufficiently highly of Rupert to offer him a generalship, if he would convert to Catholicism, an offer Prince Rupert rejected.

By 22nd August 1642, King Charles was in Nottingham, where he raised his standard. Prince Rupert joined the King with engineer and artillery officers from the Continent. Scots officers joined and the army grew. Difficulty lingered in raising and equipping the expensive cavalry regiments, although the arrival of the Prince gave this arm a considerable fillip.

In Nottingham, King Charles was considered to be at risk to any determined Parliamentary attempt on his person. On 13th September 1642, King Charles marched with his army to Derby, and then, on 20th September, to Shrewsbury, to meet up with the troops raised in Wales, and from there to Chester to consolidate the Royalist hold on this important city on the Welsh border, before returning to Shrewsbury.

Sir John Byron marched to Worcester, on 19th September 1642, to hold the city with his regiment of horse for the King. He brought with him the plate donated by Oxford University.

King Charles I addresses his officers in September 1642: Battle of Edgehill 23rd October 1642 during the English Civil War

Parliament began to form its army in June 1642. Some 80 troops of horse were raised, with 2 regiments of dragoons and 20 regiments of foot, from the Midlands and the South East of England.

On 23rd September 1642, Essex marched his Parliamentary army to Worcester, to take the city, and to interpose his army between the King and support from Wales.

Powick Bridge, 23rd September 1642: Battle of Edgehill 23rd October 1642 during the English Civil War: drawing by C.R.B. Barrett

Battle at Powick Bridge:

A feature of that period of the war was the inadequacy of each side’s intelligence services, allowing ignorance of the other side’s position and intended actions. Prince Rupert arrived in Worcester on 23rd September 1642, the same day as but in advance of Essex and ignorant of the proximity of the Parliamentary army. As a result, the small but significant action of Powick Bridge took place.

On his arrival in Worcester Prince Rupert saw that the city was without viable defences and ordered a withdrawal of the Royal forces, with the Oxford University plate.

The Parliamentary advance guard comprised a strong party of horse and dragoons. One of the troop commanders was Nathaniel Fiennes. Clarendon describes the action which resulted when Fiennes arrived at Worcester, by way of Powick Bridge: “On the sudden while [Prince Rupert] was reposing himself in the field in front of the town with Prince Maurice, his brother and the principal officers – some of his wearied troops (for they had had a long march) being by, but the rest, and most of the officers, being in the town – he espied a fair body of horse [Fiennes’ detachment] consisting of nearly five hundred, marching in very good order up a lane within a musket shot of him. In this confusion the prince and his officers had scarce time to get upon their horses, and none to consult of what was to be done, or to put themselves into their several places of command. And it may be that it was well they had not, for if all those officers had been at the heads of their various troops, it is not impossible it might have been worse. But the prince instantly declaring that he would charge, his brother, and all those officers and gentlemen whose troops were not present or ready, put themselves beside him, the other wearied troops coming in order after them.

And in this manner the prince charged the enemy as soon as they came out of the lane, and though the rebels, being gallantly led and completely armed both for offence and defence, stood well, yet in a short time many of their best men were killed and the whole body was routed and pursued by the conquerors for the space of above a mile.”

Clarendon puts the Parliamentary casualties at 40 to 50, mostly officers. The Royalist casualties seem to have been low with no officers seriously wounded or killed. Clarendon states that this was particularly surprising as the Royalists did not have time to put on their defensive armour.

Prince Rupert (on the right) with his brother, Prince Karl Louis, the Elector Palatine: picture by Sir Anthony van Dyck

Prince Rupert withdrew from Worcester leaving the city to the Parliamentary army.

Powick Bridge laid the basis of the reputation for invincibility that Prince Rupert and the Royalist cavalry acquired and which lasted until the Ironsides Cavalry took the field.

Battle of Edgehill:

On 12th October 1642, King Charles left Shrewsbury with his army, for the march to London. He took 10 regiments of horse, 13 regiments of foot, 3 regiments of dragoons and a train of 20 cannon.

Essex was at Worcester. Parliamentary garrisons from Essex’s army held Hereford, Coventry, Northampton, Banbury and Warwick. While such dispersal of force was ill-advised from a military perspective, the Parliament needed to hold as much ground as possible, to ensure its support and finances.

During this time there was negotiation between Parliament and the King, to see if the dispute could be settled without all out war. The bona fides of both sides are questionable, but each sought to convince the country that it was the intransigence of the other that was the cause of the continued hostilities.

The Royalist march was hampered by wet weather, and having to travel along a network of muddy tracks, with columns of wagons, coaches, pack horses, heavy guns, infantry and horsemen.

Essex left Worcester in pursuit on 19th October 1642, suffering the same problems for his army.

King Charles and the Royalist army arrived in Edgecote, a village outside Banbury, on Saturday 22nd October 1642. A council of war decided that the army would rest in billets, in the area to the north of Banbury, for the next day, while Sir Nicholas Byron’s Brigade, with 4 of the army’s largest cannon, assaulted Banbury, where the Parliamentary garrison comprised the Earl of Peterborough’s Regiment of foot and a troop of horse.

A reconnaissance by Lord Digby found no sign of the main Parliamentary army.

In fact the two armies were converging on Banbury. After dark on 22nd October, Essex’s army arrived at Kineton, approximately 10 miles away to the West, on the far side of the Warwick to Oxford road.

The Royalist army went into billets in villages to the North of Banbury. Prince Rupert encountered Parliamentary officers in Wormleighton, where he was proposing to billet his regiments of horse.

Prisoners taken in the ensuing skirmish revealed that the main Parliamentary army was arriving at Kineton, information then confirmed by a Royalist patrol.

Adoniram Byfield, the chaplain of

Sir Henry Cholmondeley’s Regiment of Foot, a prominent Parliamentarian

clergyman and one of the first to see the assembling Royalist army on

Edgehill on 23rd October 1642

Prince Rupert sent this news to the King, with his advice that an attack be launched immediately. King Charles consulted his other senior officers, and issued orders that the army assemble on Edgehill, overlooking Kineton, the next morning, ready for battle.

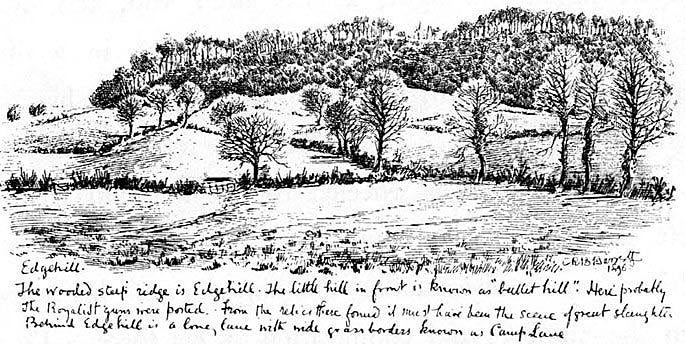

The Edgehill ridge, running west to east, lay across the road from Kineton to Banbury, rising steeply to 300 feet above Kineton.

Prince Rupert reached Edgehill at dawn, his regiments of horse arriving during the morning, and the infantry began marching in, from their billets, around midday.

The Royalist army was first seen by the Parliamentary troops at around 8am, as they were assembling for Sunday worship. Adoniram Byfield, the chaplain of Sir Henry Cholmondeley’s regiment, described watching the Royalists from the top of a hill with a ‘prospective glass’. The alarm was given and Essex’s army began to assemble to the south-east of Kineton.

The Parliamentary army was delayed in the same way as the Royalists, by the overnight billeting of the soldiers across a wide spread of villages. Some of Essex’s regiments were too far away to arrive in time for the battle.

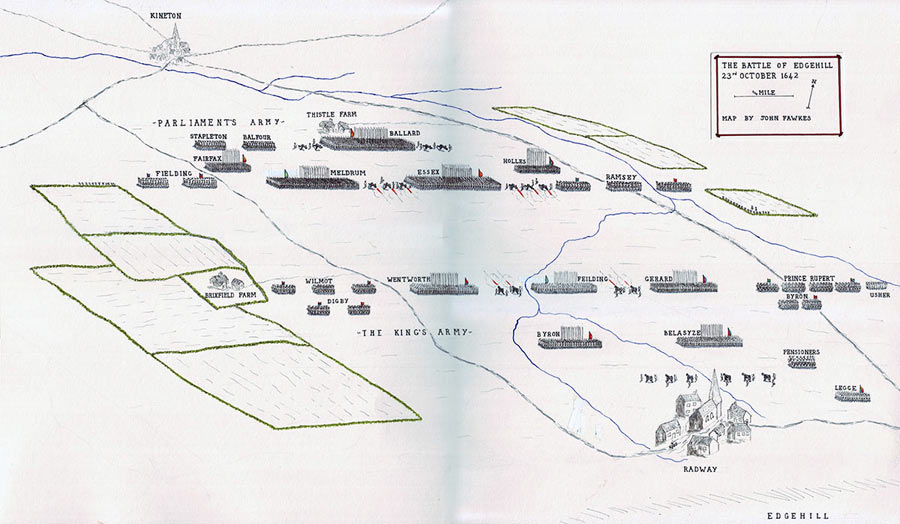

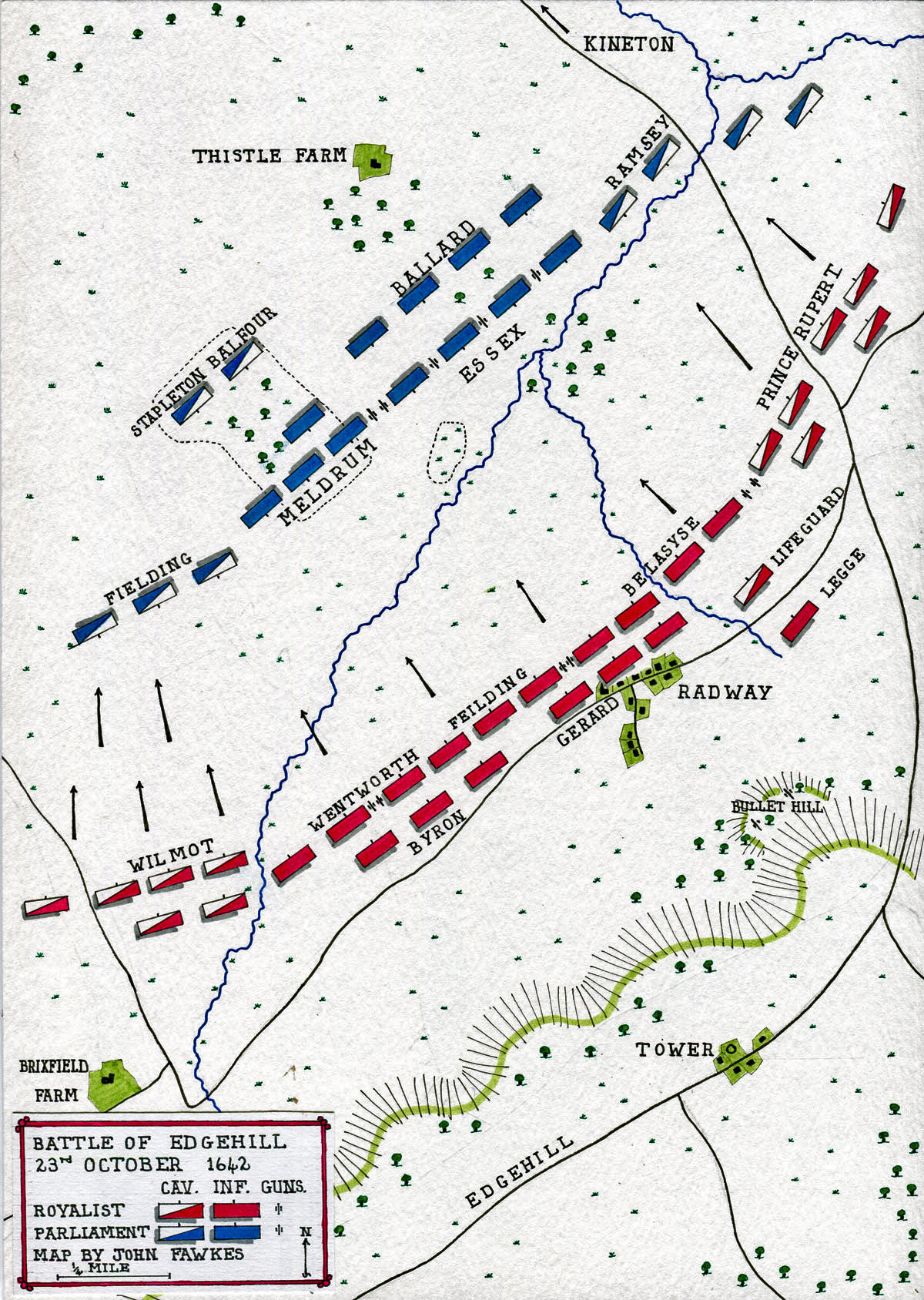

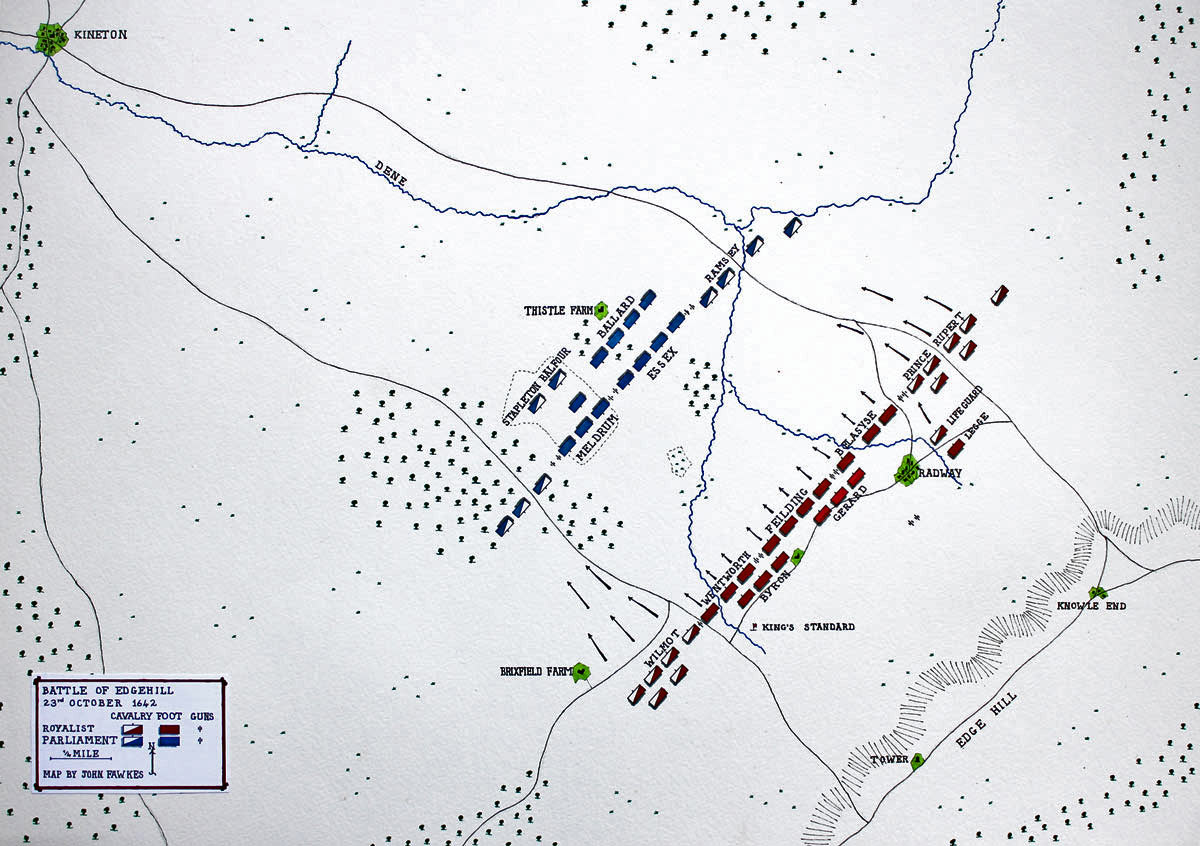

Essex formed his army across the Kineton to Banbury road, a mile short of the base of Edgehill. Lord Feilding’s regiment of horse took the extreme right flank, covered by 2 regiments of dragoons. Then came Sir William Fairfax’s regiment of foot. The Parliamentary centre was drawn up in two lines. In the first line was the brigade of foot of Sir John Meldrum, comprising the regiments of Robartes, Constable and Meldrum; and then the brigade of foot of Colonel Charles Essex, comprising the regiments of Essex, Wharton, Mandeville and Cholmondeley.

As the Earl of Essex had seen his continental service with the Dutch Prince Maurice of Dessau, it is likely that the Parliamentary foot adopted the 8 rank system of the Dutch.

In the Parliamentary second line, were, from the right, the regiments of horse of Sir Philip Stapleton and Sir William Balfour, and then Colonel Thomas Ballard’s brigade of foot, comprising the regiments of the Earl of Essex, Ballard, Brooke and Holles.

Sir James Ramsey held the Parliamentary left flank, to the north of the road, with 24 troops of horse and 500 musketeers detached from Ballard’s brigade. These musketeers held the hedges, and were positioned between the troops of horse, a common practice in Europe.

Contemporary drawing of the Battle of Edgehill on 23rd October 1642 in the English Civil War illustrating the formation of regiments of Foot with clumps of pikemen surrounded by musketeers and Horse discharging pistols

Essex’s artillery train comprised some 40 cannon. It is not clear how many were present on the battlefield. No authority states how the Parliamentary artillery was disposed, but it is likely the cannon were stationed between the regiments of the first line of foot.

Essex was restrained from advancing to the attack by a number of factors; the hill up to the Royalist position was too steep for anything but a difficult approach; his army was far from complete, due to the distribution of his regiments in billets over a wide area, with 3 regiments of foot, 11 troops of horse and 5 to 10 guns still to reach the point of assembly. Finally there were political constraints. It was far from clear that the possibility of resolving the dispute between King and Parliament by negotiation was ended.

During the frenetic months of recruiting troops for the King’s army, little planning had been devoted to formations to be adopted in battle. The King’s appointed Lord General, the Earl of Lindsey, on the morning of Edgehill, proposed to adopt the 8 rank infantry formation of the Dutch Prince Maurice, with whom he had served (with the Earl of Essex).

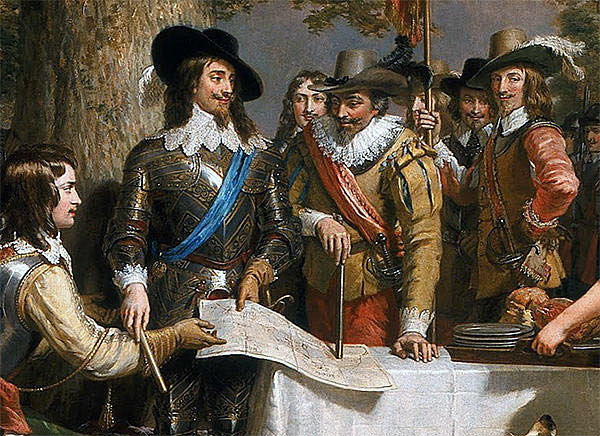

King Charles I with his advisers before the Battle of Edgehill on 23rd October 1642 in the English Civil War: picture by Charles Landseer

Prince Rupert proposed the Swedish tactics of fewer ranks and more flexible formations. Rupert was supported by Patrick Ruthven, Lord Forth, who served in the Swedish army under King Gustavus Adolphus. Sir Jacob Astley, the Sergeant Major General, with command of the foot, had served with the Dutch, but supported Prince Rupert, whose tutor Astley had been, or rather said nothing to contradict him.

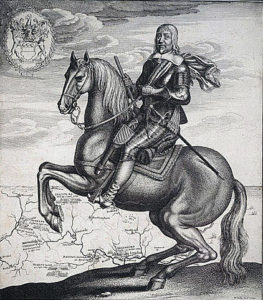

Robert Bertie, First Earl of Lindsey,

Lord General of King Charles I’s army

at the Battle of Edgehill and mortally

wounded in the battle

The King overruled Lindsey, and accepted Prince Rupert’s advice. Offended at having his authority set aside, Lindsey resigned his office of Lord General, and returned to command his regiment, asking that it be placed in a prominent position in the line.

The King’s army came down from Edgehill, and formed up on the north-west side of Radway village, facing the Parliamentary army.

The front line of the Royal army comprised 3 brigades of foot. The second line comprised 2 brigades of foot, which covered the gaps between the front line brigades.

The brigades of foot in the first line, were, from the right; the brigades of Colonel Charles Gerard, Colonel Richard Feilding and Colonel Henry Wentworth. Those of the second line, from the right, were the brigades of Colonel John Belasyze and Sir Nicholas Byron.

The Royal horse were divided into two divisions of 5 regiments each, with the division posted on the right flank commanded by Prince Rupert, and the division on the left by Henry Wilmot. The ‘Gentlemen Pensioners’, a life guard troop, commanded by Sir William Howard, were positioned to the rear of the centre of the lines of foot, together with Colonel Legge’s firelock musketeers, who will have been providing an escort for the heavy cannon.

The 3 regiments of dragoons, under Sir Arthur Aston and Colonel James Usher, held positions in the hedges on the extreme flanks, Aston on the left with 2 regiments, and Usher on the right with 1.

The Royal artillery comprised 20 cannon, commanded by Sir John Heydon, the lieutenant general of the train. As the formation adopted was in the Swedish style, the light guns will have been distributed among the infantry regiments, and the heavier cannon placed in battery at some central point.

The battle began with a mutual discharge of cannon, which appears to have been of little effect, although Parliamentary accounts claim a greater impact for their gunfire.

Prince Rupert intended to launch a cavalry attack, on his wing, at the first opportunity. Wilmot, on the left wing, was of a like mind.

The Royalist dragoons advanced on foot to clear away the ‘commanded musketeers’, accompanying and covering the Parliamentary horse on each flank.

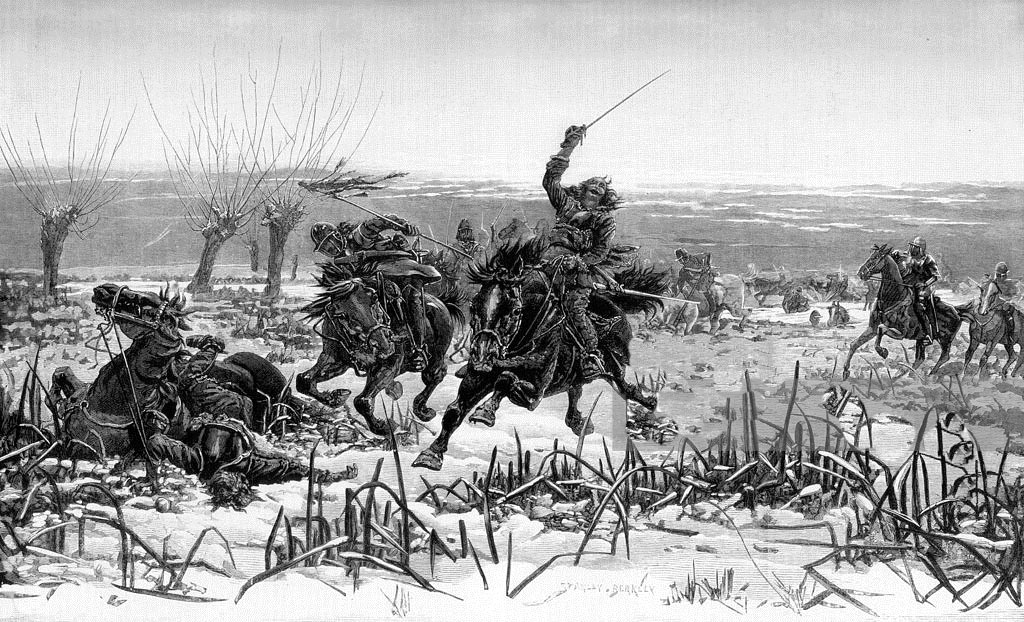

Once this operation was complete, Prince Rupert ordered his regiments of horse to advance. As Rupert’s squadrons approached the Parliamentary horse, one of Ramsey’s troops, commanded by Sir Faithful Fortescue changed sides, breaking ranks and galloping up to Prince Rupert’s horsemen, to form up with them. Prince Rupert’s regiments then charged the Parliamentary horse at a full gallop.

Ramsey’s regiments received Prince Rupert’s attack at the halt, an acceptable tactic for some schools of warfare of the time, but subsequently considered a grave error in a cavalry action, reacting only with a desultory and ineffective carbine fire. The Parliamentary troopers were either bowled over by the headlong charge of Royal horse, cut down, or fled to the rear, pursued by Prince Rupert’s men.

Sir John Byron’s second line of horse followed Prince Rupert into the attack, and the pursuit, leaving the Royalist right wing largely denuded of horse.

It is clear that the style of riding in the Royalist cavalry was that used in the hunting field; a loose rein giving the horse its head, so that it gallops at full speed. The horse, maddened with excitement, becomes almost impossible to control, until it stops through exhaustion. There is little possibility of persuading such cavalry to desist from the pursuit of a defeated foe.

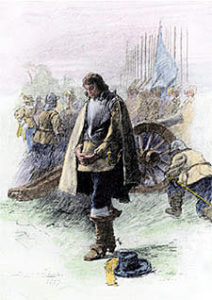

Sir Jacob Astley, Sergeant Major General

of the Royalist Foot at the Battle of Edgehill on 23rd October 1642, later Lord

Reading: picture by an unknown artist

Prince Rupert was unable to halt his cavalry, in order to take a further and constructive part in the battle that developed between the central formations of the two armies. The pursuit went through Kineton and beyond.

The cavalry action on the Royalist right was replicated on the Royalist left. Wilmot charged through Lord Feilding’s regiment, followed by the second line of Lord Digby, and the Parliamentary horse was chased back through Kineton, in a similar fashion.

Prince Rupert managed to halt 3 troops on his wing, while some 200 horse were halted on the left wing.

As the horse began their charge, the Royalist foot also advanced, led by the Sergeant Major General, Sir Jacob Astley, albeit at a more measured pace. The Royalist brigades in the second line closed up into the gaps between the front line brigades, so that there was a near solid front.

Charles Essex’s brigade, holding the left of the Parliamentary front line of foot, saw the cavalry to their left swept away by Prince Rupert’s headlong charge, and seeing the Royalist foot advancing on them, turned and fled, in spite of the efforts of their officers, from Essex down.

Fortunately for the Parliamentary side, the soldiers of Ballard’s brigade in the second line were made of sterner stuff, and they moved forward into the gap left by Essex’s vanishing regiments. Ballard’s brigade was in time to receive the charge of the 10,500 Royalist foot, with the rest of the Parliamentary first line.

After the first push of pike, the two sides recoiled, stuck their colours in the ground and began firing at each other, at point blank range.

Captain Smith’s fight for the Royal Standard at the Battle of Edgehill on 23rd October 1642 in the English Civil War

While the horse on the flanks of Essex’s army had been ignominiously put to flight, two regiments of Parliamentary horse remained on the battlefield, the regiments of Sir William Balfour and Sir Philip Stapleton, positioned to the left in the second line, behind Meldrum’s brigade.

These two regiments threw themselves at the advancing Royalist foot. Stapleton’s regiment was held by Sir Nicolas Byron’s brigade, but Balfour’s cut heavily into Feilding’s brigade of Royalist foot, capturing Feilding and two of his colonels, Stradling and Lunsford. Carrying on through the infantry, Balfour’s troopers overran the Royalist heavy guns, but possessing no nails, they were unable to spike them. They cut the drawing traces on the guns and fell back to their position in the second line.

Finding that the firelock men guarding the Parliamentary heavy battery and the gunners had fled, Stapleton moved to cover the cannon, and managed to discharge one of them, albeit at Balfour’s returning troopers.

The Earl of Essex now determined to exploit the initiative gained by his two regiments of horse, and directed an attack on Sir Nicholas Byron’s Brigade of Foot. Lord Robartes’ and Sir William Constable’s regiments of foot, supported by the horse regiments of Balfour and Stapleton, and the regiments of foot of the Lord General and Lord Brooke, charged Byron’s Royalist brigade, and drove it back, breaking up its ranks.

Captain John Smith retrieving the Royal Standard at the Battle of Edgehill on 23rd October 1642 in the English Civil War

It was at this point, that the Earl of Lindsey, leading his regiment, was shot in the leg and mortally wounded. His son, Lord Willoughby d’Eresby, stood over him, defending his fallen father with his half-pike, until he was taken prisoner.

The King’s Life Guard fought with Constable’s Regiment of foot, and during this combat, Sir Edmund Verney, the King’s Knight Marshal, was killed and the King’s Royal Standard, which Verney carried, was taken. In addition, Sir Nicholas Byron was wounded, Lieutenant-Colonel Monro of the Lord General’s regiment killed, and Lieutenant-Colonel Vavasour of the Lifeguard taken prisoner.

As the fighting raged in the centre of the battle, Sir Charles Lucas attacked the rear of the Parliamentary line, with the 200 horse he had retrieved from the Royalist cavalry attack on the left wing. While this force captured several colours and killed and wounded numbers of Parliamentary troops, they did not reach the main line, due to the number of fugitives in their way. One of Lucas’s officers, Captain John Smith of Lord Grandison’s Regiment of Horse, saw the Royal Standard and some prisoners being escorted from the field by a party of Parliamentary troopers. Smith, with one other trooper, attacked the party, retrieving the Royal Standard and freeing Colonel Richard Feilding.

Royalist attack on the Parliamentary train at the Battle of Edgehill on 23rd October 1642 in the English Civil War

The Royalist Horse from the right wing, after pursuing the Parliamentary horse as far as Kineton, pillaged the baggage they found there, seizing the coach belonging to the Earl of Essex. They were checked in Kineton by Parliamentary horse and the brigade of foot, commanded by Colonel John Hampden, coming up to take their places in the Parliamentary line, from their distant quarters.

Prince Rupert’s troopers returned to the field of battle from their pursuit, their arrival encouraging the Royalist foot to make a firm stand against the steadily advancing Parliamentary line. However the Royalist cavalry could not be persuaded to attack the Parliamentary infantry, claiming their horses were too exhausted. Prince Rupert refused to order a further attack.

Darkness was falling, and the battle petered out, both sides exhausted. King Charles was advised that he should withdraw his army from the field, but he refused, supported by the advice of Sir John Culpeper, and spent the night with his troops at the base of the hill.

Illustration of the Battle of Edgehill on 23rd October 1642 in the English Civil War: drawn in the Restoration period with uniforms of that time

It was cold, and many of the Royalist foot left their posts, to seek more comfortable quarters.

During the night, the missing Parliamentary regiments came up; Colonel Hampden’s brigade of foot, comprising 2 regiments, and Lord Willoughby’s regiment of horse. Hampden urged a resumption of the battle in the morning, but Essex refused; much of the Parliamentary Horse was missing, and several of the regiments of foot had suffered badly.

The casualties on each side seemed much worse than they actually were, due to the numbers of soldiers dispersed, either during the battle, or leaving their ranks to seek quarters, during the night.

The next day, 24th October 1642, Essex left with his army for Warwick, and the Royalists returned to the quarters they occupied before the battle, in the villages immediately to the North of Banbury. During the morning, King Charles sent Sir William le Neve to the Earl of Essex, with an offer of pardon for all members of Essex’s army who would lay down their arms, and return to their allegiance to the Crown.

Essex refused this offer, and prevented le Neve from having access to any of the Parliamentary troops.

Battle Farm, showing the spot where casualties were buried from the Battle of Edgehill 23rd October 1642 during the English Civil War: drawing by C.R.B. Barrett

Casualties at the Battle of Edgehill:

Casualties in the Battle of Edgehill are hard to quantify. Clarendon says the local clergyman, who made himself responsible for burying the dead, stated that there were 3,000 bodies. Clarendon says that, of these, 1,000 were royal troops. Later Clarendon amends his assessment to say that the King’s army suffered around 300 killed.

A problem in assessing casualties in the battle was that many of the cavalry were dispersed, either in flight or pursuit, and many of the foot soldiers left their ranks during or after the battle, either to return home or to seek shelter, perhaps resuming their ranks the next day or later. Many of the Parliamentary stragglers and deserters did not return to their army at all.

It seems likely that the Army of Parliament suffered higher casualties than King Charles’s army, from the various causes; death, wounds, capture, straggling and desertion.

It may be that the casualties of the battle were around 1,500 in dead, wounded and captured for Parliament and 1,000 for the King.

Of the senior officers, the Royalists lost the Lord General, Lord Lindsey, who died of his wound, Sir Edmund Verney, the Earl Marshal, and Lord d’Aubigny killed. Several senior officers were wounded or captured. Patrick Ruthven, Lord Forth, was appointed Lord General in place of Lindsey.

The Parliamentary side lost Colonel Lord Saint John and Colonel Charles Essex killed.

Cannon changed hands during the battle, being lost and retaken, but the only guns to be captured were 4 Parliamentary pieces, which fell into Royalist hands the day after the battle.

Robert Devereux, Earl of Essex, commander of the Parliamentary army at the Battle of Edgehill 23rd October 1642 in the English Civil War: print by Wencelas Hollar

Follow-up to the Battle of Edgehill:

Following the battle, King Charles captured Banbury on 27th October 1642, and then took his army towards London, but by a circuitous route.

The Battle of Edgehill left the Royalists with the upper hand. The rout of the Parliamentary horse on each wing gave a towering reputation to the Royalist cavalry, and, on top of his success at Powick Bridge, in particular to Prince Rupert.

It was clearly the view of Lord Clarendon, that for a time it was in the King’s power to end the war, with a settlement favourable to himself. This opportunity was due to the assumption in Parliamentary circles, and in the rest of the country, that the Royalist army had won the battle, and was more powerful than in fact it was.

This opportunity was squandered by the Royalist attack on the Parliamentary garrison at Brentford on 12th November 1642, and the illusion as to the power of the Royalist army evaporated in the confrontation with the London Trained Bands on Acton Common during the following week, when it became clear how small King Charles’s army really was, and the King was forced to retreat to Reading.

Sir Jacob Astley, Sergeant Major General of the Royalist Foot at the Battle of Edgehill on 23rd October 1642, later Lord Reading

Anecdotes and traditions of the Battle of Edgehill:

- On the Parliamentary wings at the Battle of Edgehill, the European practice was adopted of ‘interlining’ the horse with groups of ‘commanded musketeers’ on foot. The result was unfortunate. The Parliamentary horse was routed, leaving the musketeers to be cut to pieces.

- Before leading the Royalist Foot into battle at Edgehill, Sir Jacob Astley, Sergeant Major General of the Royalist Foot, knelt down and uttered the memorable prayer: “Lord, thou knowest how busy I must be this day. If I forget thee, forget thou not me.” He then stood up and shouted “March on lads.”

- It is the Verney family tradition that when Sir Edmund Verney was cut down, and the Royal Standard taken at Edgehill, Sir Edmund’s hand remained grasping the pike, although severed from the rest of his arm and body. His body was not recovered after the battle.

- Sir Edmund Verney’s eldest son, Ralph, fought for Parliament. Father and son appear in a joint memorial with their wives, in the family church at Middle Claydon.

- Captain John Smith was knighted the day after the battle by King Charles, for his feat in rescuing the Royal Standard and freeing Colonel Feilding. In his memoirs, Edmund Ludlow described Smith as recovering the Royal Standard by putting on an orange Parliamentary-style scarf and deceiving the Parliamentary trooper into handing over the Standard. This account seems inconsistent with the description given by Clarendon of Smith cutting down at least one of the Parliamentary escort, while retrieving the Standard. Ludlow fought for Parliament.

-

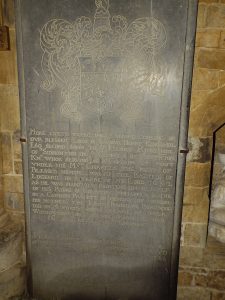

The memorial in Radway Church to the Royalist Captain Henry Kingsmill killed at the Battle of Edgehill on 23rd October 1642 in the English Civil War

A memorial in Radway Church erected by his mother commemorates the Royalist Captain Henry Kingsmill killed at the Battle of Edgehill on 23rd October 1642 in the English Civil War. The wording on the tablet reads:HERE LYETH EXPECTING THE SECOND COMING OF OUR BLESSED LORD & SAVIOUR HENRY KINGSMILL ESQ SECOND SONNE TO SIR HENRY KINGSMILL OF SIDMONTON IN THE COUNTY OF SOUTHON KNT. WHOE SERVING AS A CAPTAIN OF FOOT UNDER HIS MAJESTY CHARLES THE FIRST OF BLESSED MEMORY WAS AT THE BATTEIL OF EDGEHILL IN THE YEAR OF OUR LORD 1642 AS HE WAS MANFULLY FIGHTING IN BEHALF OF HIS KING & COUNTRY UNHAPPILY SLAINE BY A CANNON BULLET IN MEMORY OF WHOM HIS MOTHER THE LADY BRIDGET KINGSMILL DID IN THE FORTY SIXTH YEARE OF HER WIDDOWHOOD IN THE YEAR OF OUR LORD 1670 ERECT THIS MONUMENT.

- The King’s Life Guard comprised nobles of such substance that Clarendon considered there was more wealth in that one formation than in both Houses of Parliament.

- The Battle of Edgehill contained a good example of the dangers attendant on the use of firelocks. Sir Richard Bulstrode, in his memoirs, recounts that a musketeer went to replenish his powder from the regimental budge barrel, and plunged his hand into the barrel, failing to remember that he held his lighted match in his hand. A considerable amount of powder was detonated, and many soldiers killed.

- Bulstrode states that Prince Rupert drew up the King’s infantry 6 deep. While showing that the dispute between the Dutch method and the Swedish method was resolved in favour of the Swedish, this episode is an illustration of the extent of Prince Rupert’s influence in the Royalist Army, Prince Rupert’s appointment being ‘General of the Horse’. Lord Lindsey commanded the army, and Sir Jacob Astley held the post of Sergeant Major General of the Foot, with the responsibility for drawing up the foot for battle. The Royalist Horse was drawn up 3 deep, in the Swedish manner.

- Armies of the period did not necessarily wear uniform. Each side would be identified by some form of badge or mark. At Edgehill, the Parliamentary army wore orange scarfs. Some 17 or 18 of Sir Faithful Fiennes’ troopers failed to remove their scarfs when changing sides, and were cut down by Royalist horse.

- Edmund Ludlow fought at Edgehill in the Earl of Essex’s lifeguard. He was wearing armour and, after dismounting during the battle, found it extremely difficult to remount.

- Many of the wounded, forced to lie on the battlefield during the night, were saved by the cold weather, which froze their wounds and stopped the bleeding.

- It is a matter of record that, after the battle, surgeons saved several lives by use of the operation of trepanning the skulls of soldiers with head wounds.

- A local woman, Hester Whyte, submitted a petition to Parliament to be recompensed for caring for several wounded soldiers of Essex’s army for 3 months after the battle, often sitting up all night with them, and using her own resources to feed them. Several locals in the Banbury area were paid sums by Essex’s army for caring for wounded soldiers after the Battle of Edgehill.

- Most, if not all the Parliamentary regiments, possessed chaplains at Edgehill. After the battle, many of the chaplains left and went home, although it is not clear why. Two chaplains, Adoniram Byfield and Thomas Case, published accounts of the battle. C.H Firth describes the Parliamentary chaplains as ‘the first war correspondents’, many of them keeping records of their regiment’s actions.

Tale of Edgehill: Battle of Edgehill 23rd October 1642 in the English Civil War: picture by John Seymour Lucas

References for the Battle of Edgehill:

The King’s War by C.V. Wedgwood

The English Civil War by Peter Young and Richard Holmes

History of the Great Rebellion by Clarendon

Cromwell’s Army by CH Firth

British Battles by Grant Volume I

Edgehill 1642 by Peter Young

The previous battle in the British Battles series is the Spanish Armada

The next battle in the English Civil War is the Battle of Seacroft Moor