The siege and destruction in Hampshire during the English Civil War of one of England’s greatest houses between 1642 and 14thOctober 1645

Oliver Cromwell at the Storming of Basing House on 14th October 1645 during the English Civil War: picture by Ernest Crofts

The previous battle of the English Civil War is the Battle of Naseby

The next battle of the English Civil War is the Battle of Dunbar

To the English Civil War index

Battle: Siege of Basing House

War: English Civil War

Dates of the Siege of Basing House: Basing House was intermittently under attack between 1642 and 14th October 1645 when it was finally stormed by Oliver Cromwell’s men.

Place of the Siege of Basing House: In the village of Old Basing to the east of Basingstoke in Hampshire.

Combatants at the Siege of Basing House:

The Royalist forces of King Charles I against the forces of Parliament.

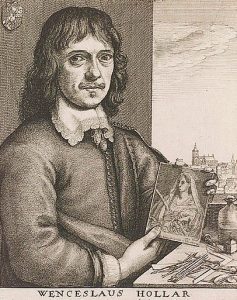

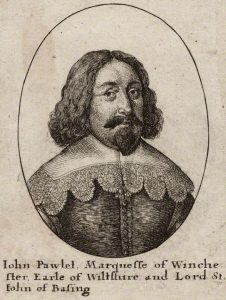

John Paulet 5th Marquess of Winchester the owner and defender of Basing House between 1642 and 1645 during the English Civil War: engraving by Wencelaus Hollar himself a member of the Basing House garrison

Generals at the Siege of Basing House: The garrison of Basing House was headed by the Marquess of Winchester, the owner of Basing House and a senior Catholic member of the English nobility. From the introduction of the King’s troops into Basing House as the garrison the military commander was Colonel Rawdon until the withdrawal of the non-Catholic troops in 1645, when command fell on Lieutenant-Colonel Robert Peake.

The initial Parliamentary assault on Basing House in 1642 was carried out by Colonel Richard Norton. The assault was renewed by Sir William Waller in 1643 and by Colonel Norton again in 1644. The final attack in which Basing House was taken by storm and destroyed was conducted by Oliver Cromwell in 1645.

Size of the armies at the Siege of Basing House:

So far as they are known these figures are given at various stages in the main text.

Winner of the Siege of Basing House: Basing House resisted the attempts of the Parliamentary armies to capture it until the final assault by Oliver Cromwell on 14th October 1645 when Basing House was stormed and destroyed, with all the members of the garrison put to the sword or captured, other than a few escaping over the walls.

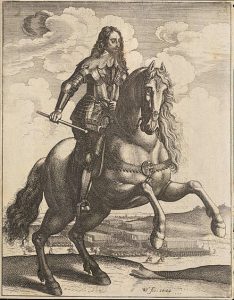

King Charles I: Siege of Basing House 1642 to 1645 during the English Civil War: engraving by Wencelaus Hollar himself a member of the Basing House garrison

Uniforms, arms and equipment at the Siege of Basing House:

See this section in the Battle of Edgehill.

Background to the Siege of Basing House:

The origins of the English Civil War are dealt with under this section in the Battle of Edgehill.

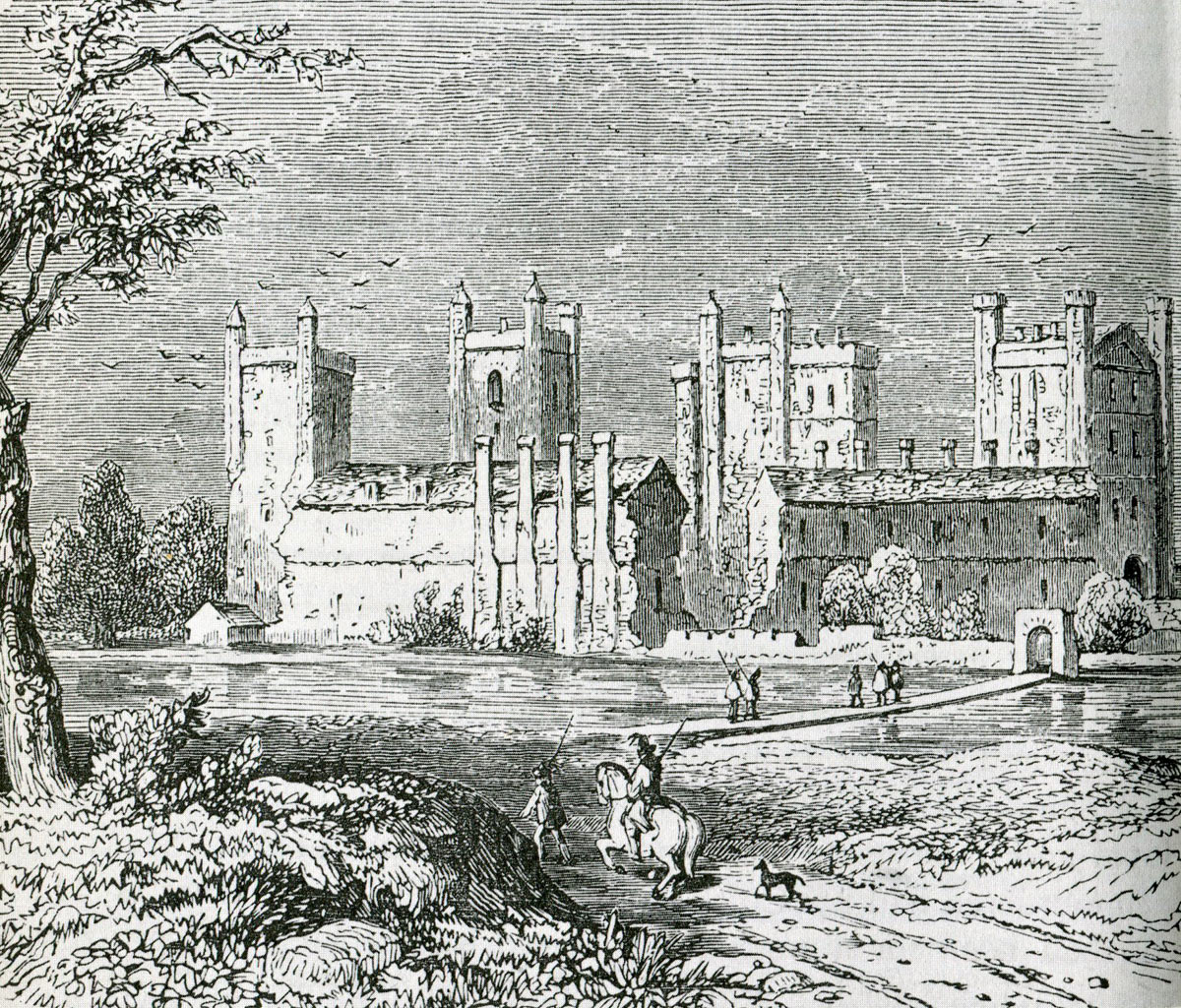

The origins of Basing House:

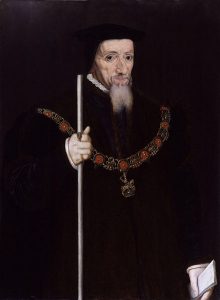

Basing House was built in the 16th Century by Sir William Paulet. Sir William Paulet began his royal service in the employ of Cardinal Wolsey under King Henry VIII. After the fall of Wolsey Paulet became Comptroller of the Royal Household and was unusual in royal service surviving in post for the rest of the reign of King Henry VIII. King Henry VIII visited Basing House in 1535. Sir William Paulet became Treasurer of the Royal Household and was appointed Lord St John. In 1545 Paulet was appointed Governor of Portsmouth and was present with the King at the sinking of the Mary Rose.

William Paulet 1st Marquess of Winchester and builder of Basing House holding the staff of office of Lord High Treasurer

Under King Edward VI Sir William Paulet became Lord Treasurer of England and ennobled as Earl of Wiltshire and later as Marquess of Winchester.

In 1554 Queen Mary spent her honeymoon at Basing House with her husband King Philip of Spain.

Paulet retained his appointments under Queen Elizabeth who stayed at Basing House twice. Paulet retired from public life in 1570 and died in 1572, reputed as owning most of Hampshire and to be of immense wealth.

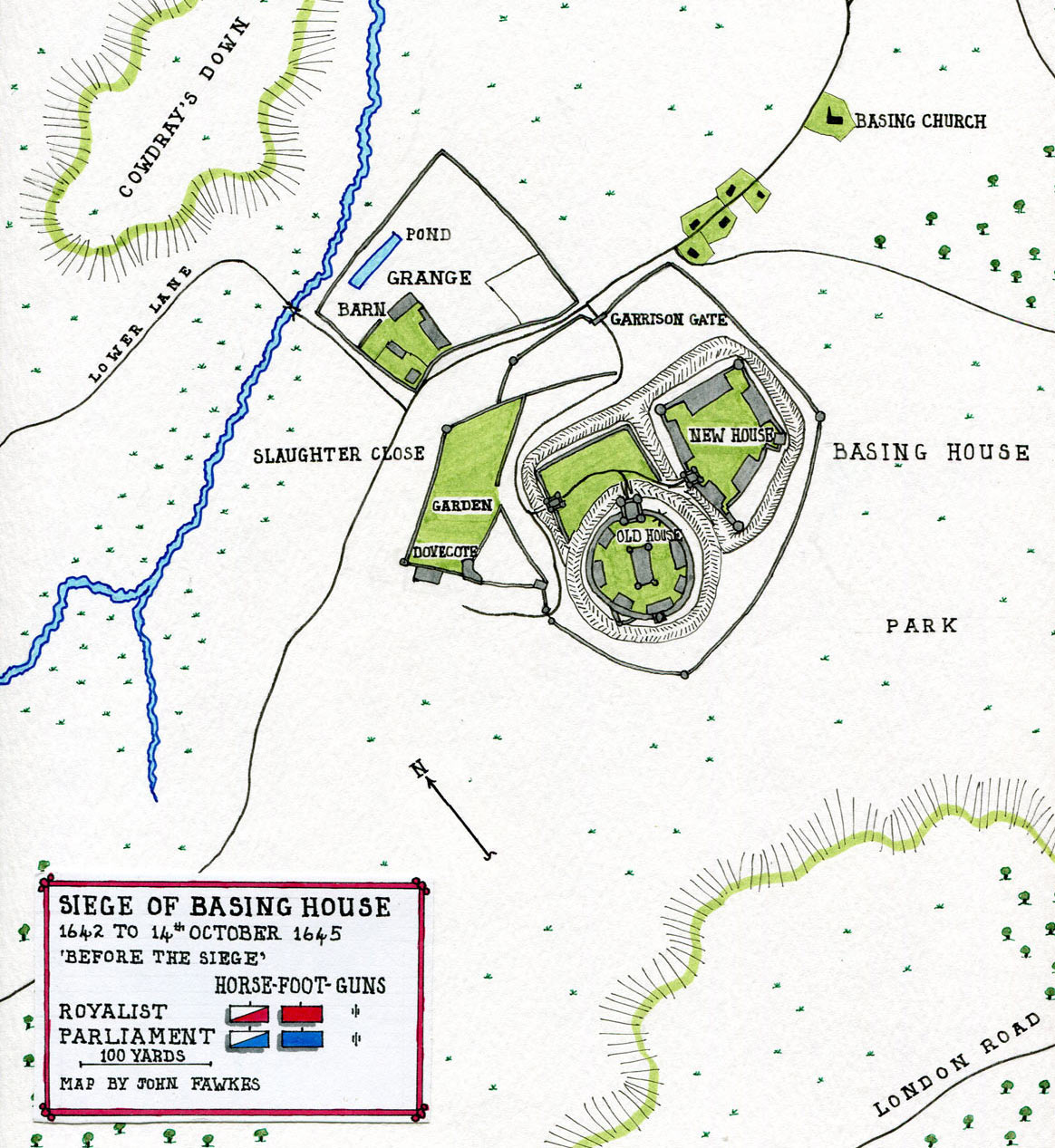

Sir William Paulet built Basing House on the mound at Basing that had been a Norman motte and bailey. Dissatisfied with the first house Paulet built a second house immediately alongside the first. The two houses were given the labels of ‘the Old House’ and ‘the New House’. Together the two houses set in 14 ½ acres amounted to a building reputed to be second only to Windsor Castle in size.

Queen Elizabeth stayed at Basing House on four occasions, the last being in 1601, her host being William 4th Marquess of Winchester, great-grandson of the 1st Marquess. King James I continued the tradition of visiting Basing House.

The expense of the Royal Visits was enormous as the Royal Retinues regularly comprised up to 2,000 persons. The 4th Marquess of Winchester is said to have pulled down part of the house to reduce its attraction to his sovereign and was forced to sell estates to meet the substantial debts he and his forbears incurred in entertaining their sovereigns.

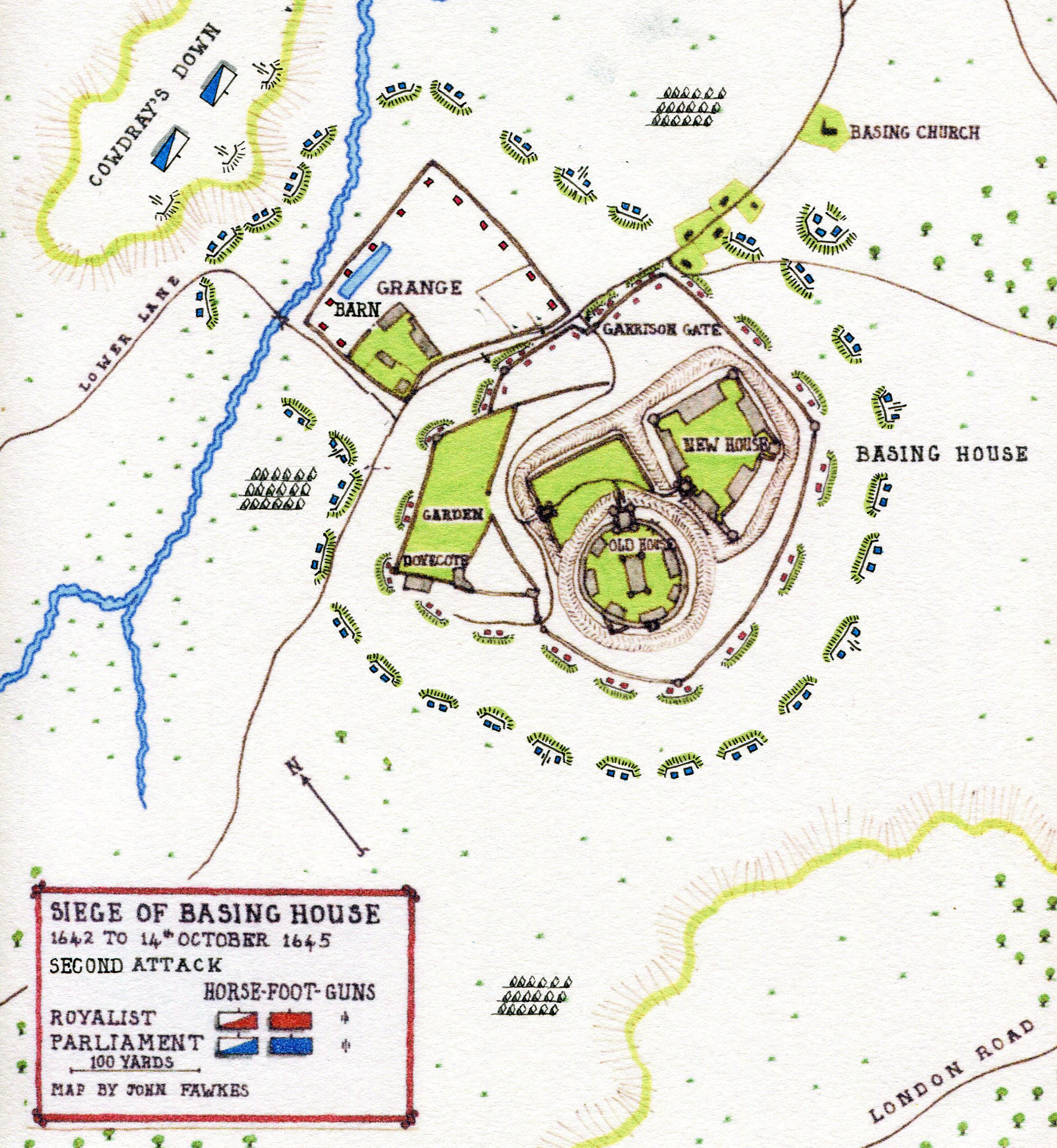

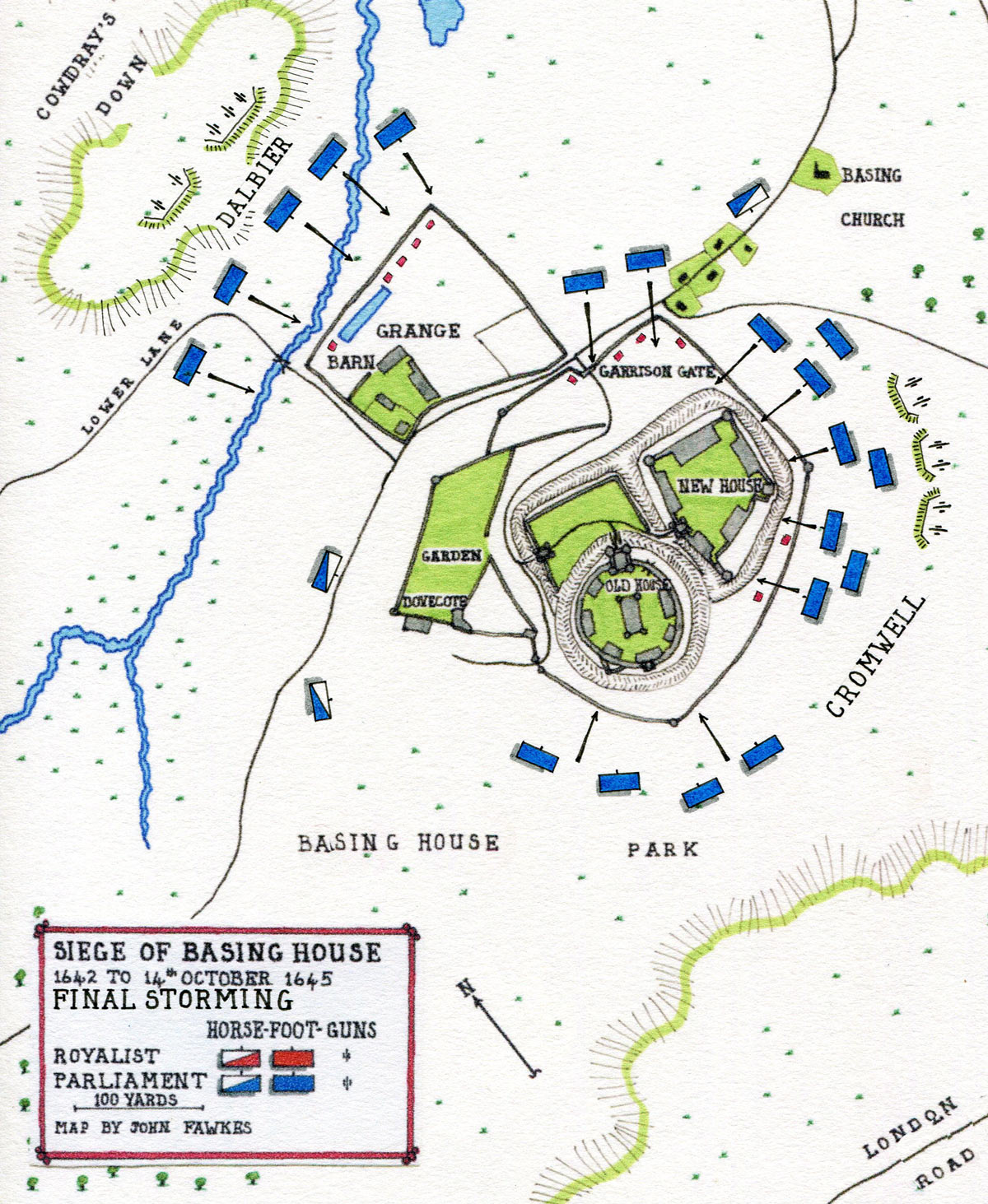

Map of Basing House: Siege of Basing House 1642 to 1645 during the English Civil War: map by John Fawkes

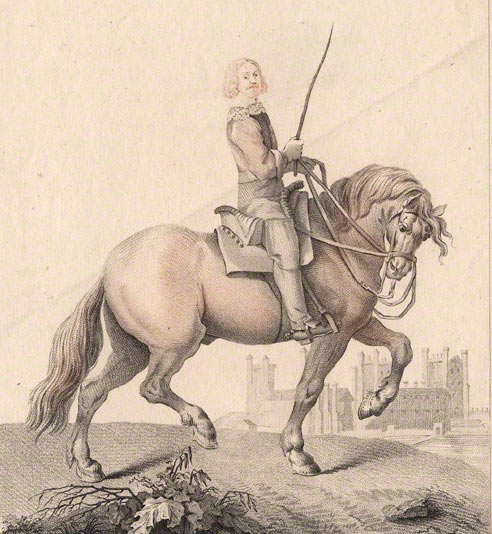

The 5th Marquess of Winchester lived from 1598 to 1675 and was a prominent Catholic. His Catholicism precluded him from taking an active role in the political life of the country other than in the Catholic community.

John Paulet 5th Marquess of Winchester the owner and defender of Basing House between 1642 and 1645 during the English Civil War with Basing House in the background: engraving by John Adam

The 5th Marquess’s commitment to his religion is in contrast to the attitude of his ancestor the 1st Marquess who is reputed to have changed religion between Catholicism and Anglicanism five times in order to fit in with the changes of monarch and to keep his prominent role in government. The 6th Marquess became an Anglican on reaching adulthood to the dismay of the Catholic community in Hampshire which looked to the Winchesters for leadership and protection.

It would appear that by the beginning of the English Civil War in 1642 the 5th Marquess of Winchester was living in London, the upkeep of Basing House as a residence being beyond his reduced resources. Eventually bringing his shaky finances under control the 5th Marquess attended court and became a friend and confidant of Queen Henrietta Maria, herself a Catholic.

With the impending war the 5th Marquess of Winchester left London and returned to Basing House fearing the civil upheaval in London and the danger to himself as a practising Catholic in the feverish Puritan atmosphere of the capital.

According to his diary of the Siege of Basing House the Marquess of Winchester was initially inclined to neutrality in the dispute between King and Parliament. He finally committed himself to support King Charles I and proved himself a steadfast Royalist, refusing to submit himself or Basing House to Parliament until his house was stormed and destroyed in 1645 by Oliver Cromwell.

It is reported that the Marquess built up a substantial store of weapons in Basing House, said to be sufficient for 1,500 men, but was ordered to dispose of them by Parliament and did so. It is difficult to accept this report. If there was such a store it would have been of considerable significance in a country short of weapons for the assembling armies, particularly to the King and it is hard to see that the impecunious Marquess would have spent the considerable sum necessary for the purchase of these weapons when he was inclined to neutrality.

Account of the Siege of Basing House:

Remains of the Old House of Basing House looking north across the bridge: Siege of Basing House 1642 to 1645 during the English Civil War

The dimensions of Basing House:

The area defended by the Royalist garrison was some 14 acres. At its centre stood the ‘Old House’, a substantial brick built mansion surrounded by a 100 foot dry moat and entered by two succeeding and large gate towers. Immediately to the east stood the ‘New House’ a five storey structure brick built and again substantial. Both buildings stood on the top of the hill originally the site of the Norman keep. To the west of the hill-top was the large walled garden with three towers along its boundary, the southernmost being a dovecote. The walls and towers of this garden still stand in their original condition. A single musket loop-hole remains unblocked in the wall.

View through the sole remaining musket loop-hole in the western perimeter wall of Basing House overlooking Slaughter Close: Siege of Basing House 1642 to 1645 during the English Civil War

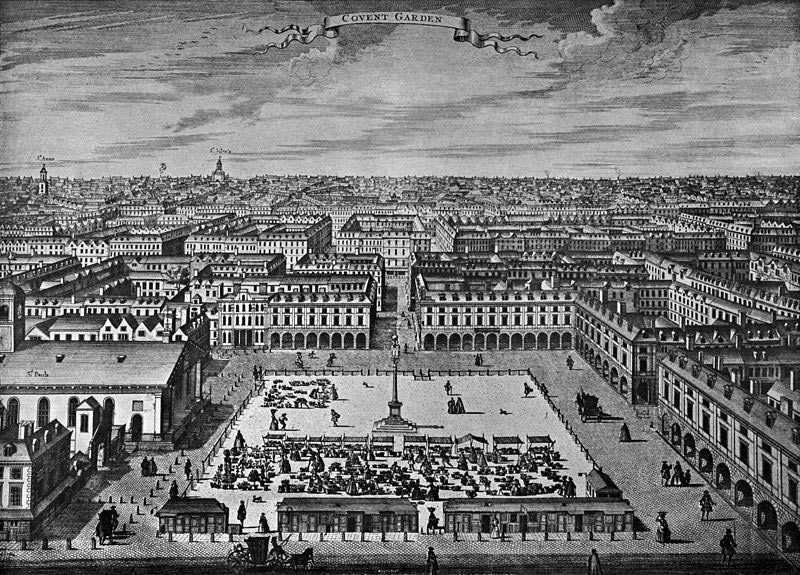

The main street of Old Basing village ran along the northern boundary of the grounds of Basing House. The perimeter wall of Basing House ran along the south side of the lane with its outer gate in the ‘Garrison Tower’ opening onto the lane.

On the north side of the lane outside the perimeter wall lay the Grange, the farming centre and storehouse for Basing House. Within the Grange area stood and still stands the ‘Great Barn’ or ‘Bloody Barn’, one of the few buildings used in the siege to be still standing.

Beyond the Grange was Cowdray’s Down an area of rising ground used by the Parliamentary forces to position batteries during the various attacks.

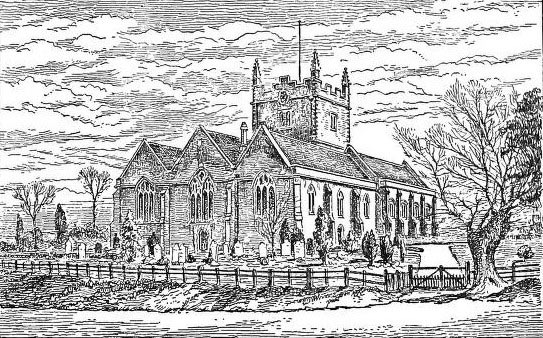

Up the village street to the east lay St Mary’s Church used during the various stages of the siege by the Parliamentary troops as a billet, dressing station and stables for their horses. The Paulet graves were broken open and the lead from the coffins used for bullets.

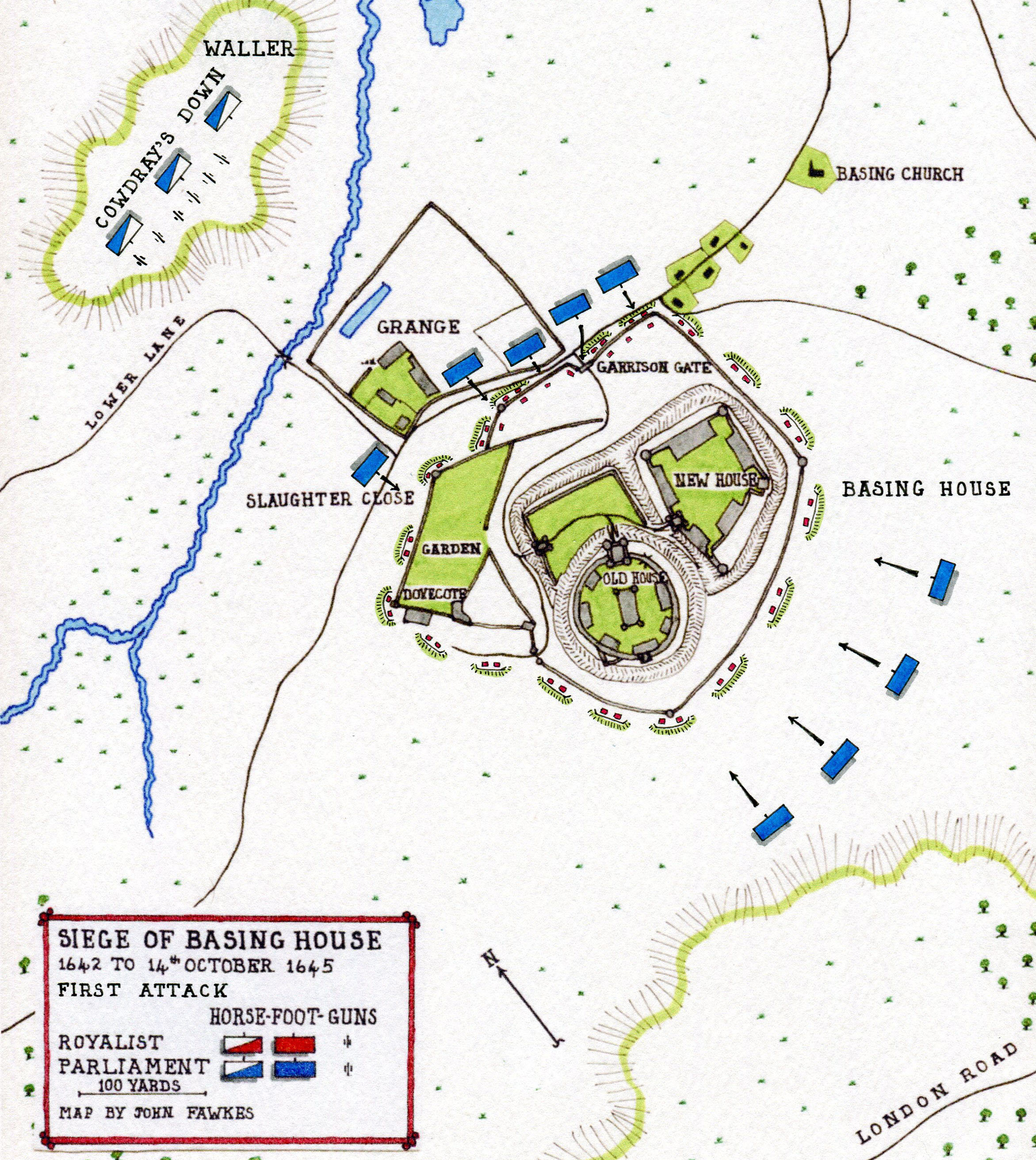

Map of the First Attack on Basing House on 6th November 1643: Siege of Basing House 1642 to 1645 during the English Civil War: map by John Fawkes

The First Attack on Basing House:

Basing House was described in Parliamentary circles as a ‘nest of papists’ and as such attracted particular opprobrium. In addition Basing House’s position on the main road from London to the West Country with parties of Royalists from Basing House preying on Parliamentary convoys, the size and richness of the house, the prominence of its Catholic owner and that some 150 Royalist sympathisers took refuge at Basing House bringing their valuables and money with them all made it a target for Parliamentary action.

In July 1642 the Marquis of Winchester petitioned King Charles I at Oxford that a Royalist garrison be provided for Basing House. This was acceded to and a garrison dispatched under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel Robert Peake. Peake marched with 100 musketeers from Colonel Marmaduke Rawdon’s Regiment and was supported by a body of Horse commanded by Colonel Sir Henry Bard.

Peake and Bard arrived at Basing House in time to intercept the first attack by Parliamentary troops comprising a Troop of Horse and one of Dragoons commanded by Colonel Richard Norton a local Parliamentary commander living in Alresford. Norton was driven off and Peake moved into Basing House to assist the 5th Marquess set the house in a state of defence.

Oliver Cromwell meets the 5th Marquess of Winchester after the storming of Basing House on 14th October 1665: Siege of Basing House 1642 to 1645 during the English Civil War: picture by Ernest Crofts

Peake’s party was soon joined by Colonel Marmaduke Rawdon himself with the rest of his regiment, only some 150 men. Rawdon became the military governor of Basing House with Peake as his lieutenant-governor.

King Charles I also sent his Surveyor of Buildings the architect Inigo Jones to assist in the building of defences.

Sir William Waller Parliamentary commander of the first major assault on Basing House in November 1643: Siege of Basing House 1642 to 1645 during the English Civil War

An earth work was built to enclose the whole of the Basing House site. Buildings outside the Basing House perimeter that might provide cover for an attacking force were cleared away.

To convert the Old House into a stronghold windows and doors on the lower levels that might be used to force entry were bricked up leaving the main gate tower at the end of the bridge as the only place of entrance and egress.

Of course the fate of Basing House depended on the wider conduct of the war. In September 1643 the Parliamentary commander the Earl of Essex fought his way back to London following his foray to relieve the City of Gloucester.

Essex fought the First Battle of Newbury on 20th September 1643 against the Royalist army of King Charles I that was attempting to block his return to London.

Newbury was only 20 miles from Basing House.

The first substantial attack on Basing House- there had been small raids during the year easily driven off- was carried out on 6th November 1643 by Sir William Waller.

Waller assembled his troops at Windsor Castle, 500 Foot, 500 Horse, 200 Dragoons, several light to medium guns, 10 heavy guns and 6 ‘small drakes’ or light field guns and marched to Farnham.

For the attack on Basing House Sir William Waller called on 3 regiments of the London Trained Bands, some 2,000 men and probably the most reliable Foot available to Parliament in the South of England at that time.

From Farnham Sir William Waller marched the 20 miles to Basing House.

The garrison of Basing House was around 400 men with a number of women prepared to assist by casting bullets and other activities.

Sir William Waller was a master at covert advances and arrived unexpected by the Royalist garrison. Waller’s men marched into Basing village along the road past Basing House shrouded in fog. In the early afternoon the fog lifted and the garrison were able to see the Parliamentary troops that until then they could only hear.

500 Parliamentary musketeers of the Tower Hamlets Regiment under Captain William Archer took up position in the lane and opened fire on the Basing House perimeter wall while Waller’s guns moved up onto Cowdray’s Down and were arranged in batteries.

Parliamentary emissaries delivering a summons to surrender: Siege of Basing House 1642 to 1645 during the English Civil War: picture by Ernest Crofts

At about 4pm the Parliamentary batteries opened a short bombardment before a parley was arranged. Waller sent a message inviting the Marquess of Winchester to surrender Basing House for the use of the ‘King in Parliament’, the expression used to indicate surrender to Parliament. Winchester’s reply made it clear that he intended to maintain Basing House in the interest of the King alone.

Two hours later Sir William Waller sent a second message by hand of drummer offering free passage to the Marchioness and all the women and children in Basing House. This offer was also rejected. The Royalist women intended to take their full part in defending Basing House in the interest of the King.

During the night a further Parliamentary bombardment was fired and Waller’s men began to build a breastwork.

Early the next morning, 7th November 1643 a further bombardment was fired and at 9am an assault on the Basing House perimeter was launched from Cowdray’s Down at the north wall bordering the lane.

The ‘Bloody Barn’ sole remaining building from the Basing House Grange: Siege of Basing House 1642 to 1645 during the English Civil War

Captain Clinson led the Parliamentary attack and stormed the Grange. The Parliamentary troops there came to a halt, while a heavy fire by the musketeers was aimed at pistol shot range on the outer wall and the batteries on Cowdray’s Down pounded the Old and New Houses behind the wall.

The Grange was found to contain a considerable amount of food supplies into which the Parliamentary troops tucked in turn.

To prevent these supplies remaining in Parliamentary hands a Royalist counter-attack was launched on the Grange in which the Parliamentary Officer Captain Clinson was killed.

In mid-afternoon heavy rain came on extinguishing the musketeers’ fuses and making firing the cannon almost impossible. Waller ordered a retreat out of range of Basing House to await drier conditions, but the rain continued through the night.

Waller acknowledged the effect of the wet weather on his battle weary men and the next morning marched them off to Basingstoke and other surrounding towns and villages to seek shelter. While in Basingstoke ladders were acquired to storm the walls.

On Sunday 12th November 1643 Sir William Waller led his men back to Basing House and launched a further attack preceded by a two hour bombardment from his batteries on Cowdray’s Down.

Following the bombardment the Parliamentary Foot attempted to storm Basing House from all sides.

The main Parliamentary attack is said to have been launched on the north wall and the north-east corner of the wall. The target for this part of the Parliamentary assault seems to have been the New House. The assaulting parties put ladders against the wall but do not seem to have penetrated into the compound.

An additional assault was made on what is described in the records as ‘the gate’. This is taken to be the Garrison Gate.

Exploding a petard fixed to a castle gate: Siege of Basing House 1642 to 1645 during the English Civil War

It would seem that a petard was fixed to the gate and successfully fired but failed to blow in the Garrison Gate due to the barricade erected behind.

It is reported that an ‘ingenious German’ knocked loop-holes in a flanking wall enabling Royalist defenders to fire into the Parliamentary attacker’s intent on exploding the petard attached to the Garrison Gate, ‘whereupon the rebels lost heart and men as well’.

Inside Basing House all the defenders pitted themselves against the Parliamentary troops attempting to storm the outer wall. It is said that the Marchioness Honora and the ladies of the garrison took to the roof and showered bricks and slates onto the attackers.

The assault on the south side of Basing House across the open parkland was pressed less vigorously. The Parliamentary musketeers became confused and the succeeding ranks fired into the first ranks inflicting casualties on their own side while facing a heavy fire from muskets and guns firing case shot. The attack was driven back and the Parliamentary soldiers could not be induced to resume it. These troops suffered some 70 casualties.

The assault on Basing House continued until dark when it was abandoned. By this time the cold autumn rain was falling and continued through the night. At 10pm Parliamentary soldiers brought the guns back into camp and others buried the dead.

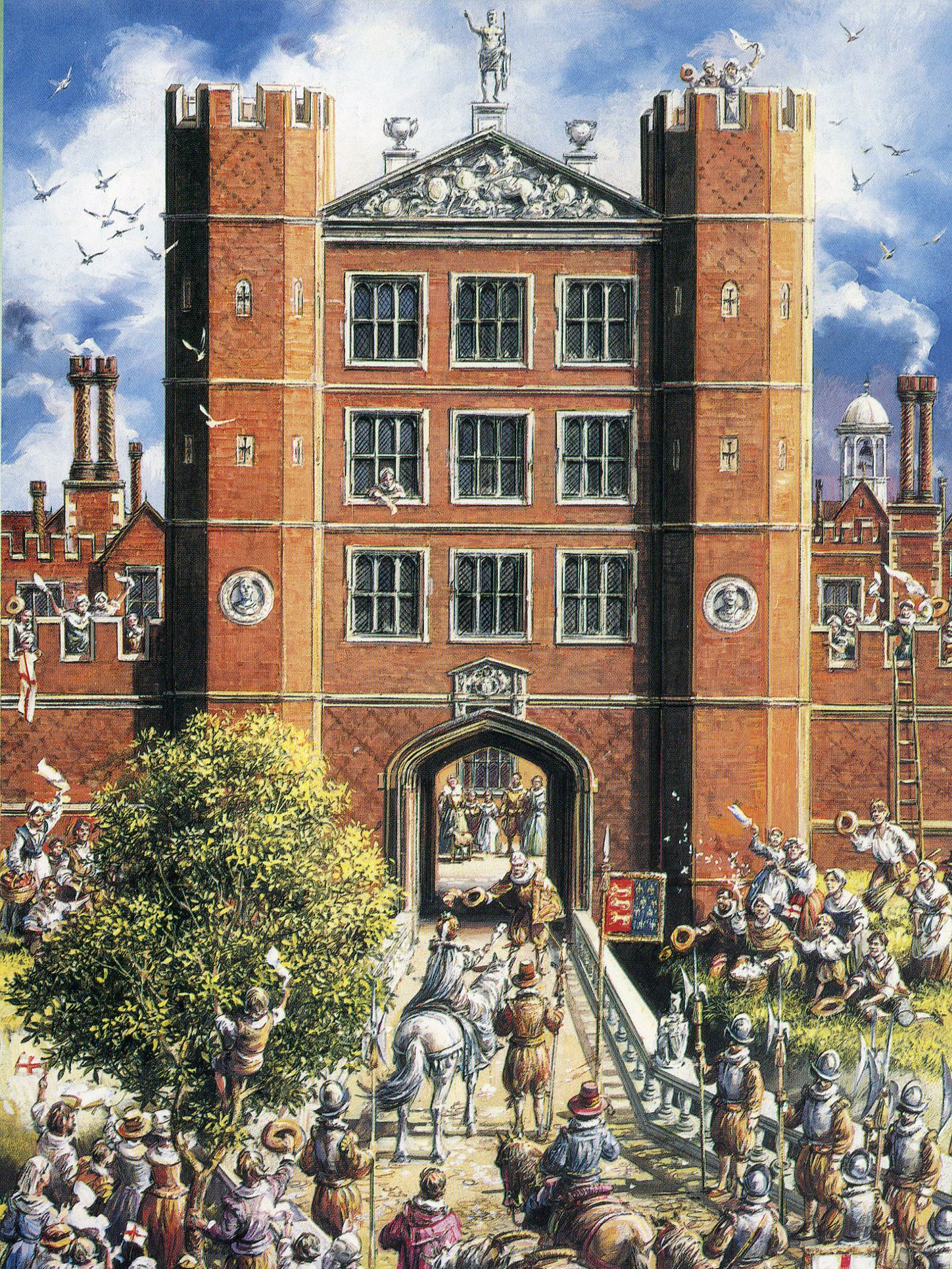

Reconstruction of the Great Gate House of the Old House at Basing House: Siege of Basing House 1642 to 1645 during the English Civil War

The failure of the assault is attributed by the Royalist periodical Mercurius Aulicus to the youth and inexperience of the London Trained Bands.

With daybreak the rain turned to sleet and snow causing Sir William Waller to take his dispirited troops back to Basingstoke.

On Tuesday 14th November 1643 Sir William Waller received news that the Royalist Commander Lord Hopton was advancing from Winchester to relieve Basing House with some 5,000 troops. Some skirmishing took place between the two forces following which Sir William Waller marched back to Farnham.

The Marquess of Winchester in his ‘Siege Diary’ described Waller’s attack on Basing House: ‘having dishonoured and bruised his army whereof abundance were lost, without the death of more than two in the garrison, and some little injury to the house by battery.’

Map of the Second Attack on Basing House from 11th July 1644: Siege of Basing House 1642 to 1645 during the English Civil War

The Second Attack on Basing House:

On 29th March 1644 Sir William Waller won the Battle of Cheriton following his successes at Alton and Arundel. The Royalist army took refuge at Basing House following its defeat.

One of the consequences of this downturn in Royalist fortunes was that the Marquess’s brother Lord Edward Paulet formed a conspiracy to hand Basing House to Sir William Waller.

The conspiracy came to light on the changing sides of Sir Richard Grenville who deserted from Waller’s army and rode to Oxford with a troop of Horse. Once at Oxford Grenville revealed the plot to the Royalist commanders who sent an urgent dispatch to the Marquess. The conspirators were arrested and confessed to their intentions.

The conspirators were hanged but Lord Edward Paulet was spared. His punishment was to be appointed the garrison hangman, his first task being to execute his fellow conspirators.

In May 1644 Sir William Waller and the Earl of Essex marched in pursuit of the King’s army, with Essex eventually marching off to the south-west. Waller was defeated at Cropredy Bridge on 29th June 1644 and Essex was forced to leave his army to surrender at Lostwithiel in Cornwall on 2nd September 1644.

In the meantime the second major Parliamentary assault on Basing House was launched by the same Colonel Richard Norton seen off by the arrival of Lieutenant-Colonel Peake’s Royalist garrison in July 1642.

The trigger for this second assault was a raid conducted by the Basing House garrison on the Parliamentary troops stationed at Odiham, a town some six miles away from Basing House.

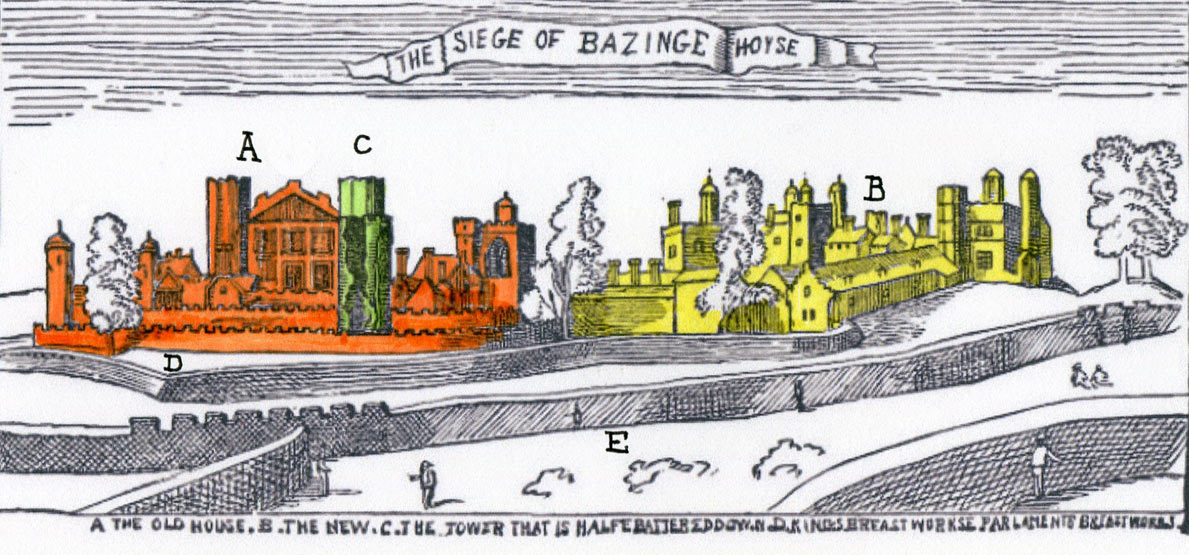

View of Basing House from the south side during the siege: A The Old House B The New House C The Tower that is Half Battered Down D King’s Breast Works E Parliament’s Breast Works: Siege of Basing House in the English Civil War: engraving by Wencelaus Hollar himself a member of the garrison: this is probably the only reliable contemporary image of Basing House before its destruction after the Siege in 1645 (colour added)

A spy warned Colonel Samuel Jones the Parliamentary governor of Farnham Castle of the impeding Royalist raid on Odiham. 80 Horse and 200 Foot from the Basing House garrison marched during the night towards Odiham to be attacked by Colonel Norton with a large body of Parliamentary Horse and Colonel Jones with a body of Foot. Many of the Royalist foot soldiers were captured and the mounted men pursued back to Basing House.

The prisoners comprised Captain Rowland, Lieutenant Rowland, Lieutenant Ivory, Ensign Coram, William Robinson the Marquess’s surgeon and 96 other soldiers. Major Langley was captured but disguised himself as a tinker and was released as of no consequence.

Pursuing the fleeing Royalist raiding party Colonel Norton appeared before Basing House with 3 Troops of Horse in the early hours of the morning and tried to entice the garrison out to fight him, his trumpeter sounding.

The losses in the Odiham adventure left Basing House with a garrison of around 175 men.

Norton arrived before Basing House and began the blockade on 11th July 1644.

The south-west corner of the perimeter wall of Basing House showing the ornamental garden and the dovecote tower: Siege of Basing House 1642 to 1645 during the English Civil War

The force Colonel Richard Norton deployed comprised 5 Surrey companies commanded by Sir Richard Onslow, 6 Sussex companies commanded by Colonel Herbert Morley and 2 companies of Colonel Jones’s Greencoats from Farnham Castle (the Green Coats had been part of Sir William Waller’s force in the first attack on Basing House). Norton also deployed his own regiment of Horse and a regiment of Foot, a body of around 2,000 men in all.

In addition 2 mortars and a quantity of heavy artillery were added to the besieging force at the end of July 1646, the mortars firing 36 pound stone shot.

With the assumption of a regular siege the Parliamentary troops dug works to encircle Basing House along its western, southern and eastern boundaries. On the northern boundary of Basing House the presence of the lane, Grange farm buildings and the marshland between the lane and the River Loddon made the digging of the work more difficult. Once finished Basing House was cut off.

The Parliamentary artillery was established in batteries and began a regular bombardment of the walls and buildings of Basing House. It would seem that the deployment of the Parliamentary guns was carried out without great skill and relatively little damage was inflicted.

The Storming of Basing House on 14th October 1645: Siege of Basing House 1642 to 1645 during the English Civil War

Colonel Morley’s Sussex companies took responsibility for the Parliamentary works on the south side of Basing House in the area of the Park while Sir Richard Onslow’s Surrey companies held the area of the lane and the positions on the west and east side of Basing House. The Parliamentary Horse patrolled the perimeter to ensure that no supplies were brought into Basing House.

The garrison, now around 250 men, carried out successful sallies to raid the siege works.

Shortages were quickly felt in Basing House. There was no mill within the perimeter so that corn could not be ground. Essential supplies of food and ammunition ran dangerously low.

Colonel Henry Gage’s Relief Column:

The Royalist main headquarters lay at Oxford. King Charles I was in the west country (see the Battle of Lostwithiel 11th August to 2nd September 1644). Oxford was commanded by a governor Sir Arthur Aston and a Council. The city was the gathering place for Royalist nobility and gentry displaced from their usual residences by the war. Oxford was being fortified and provisioned to ensure its safety from capture by the neighbouring Parliamentary forces, Major-General Browne in Abingdon with a powerful force with which he conducted raids against Oxford and Sir William Waller who lay at Banbury with the remains of his army, badly beaten at the Battle of Cropredy Bridge.

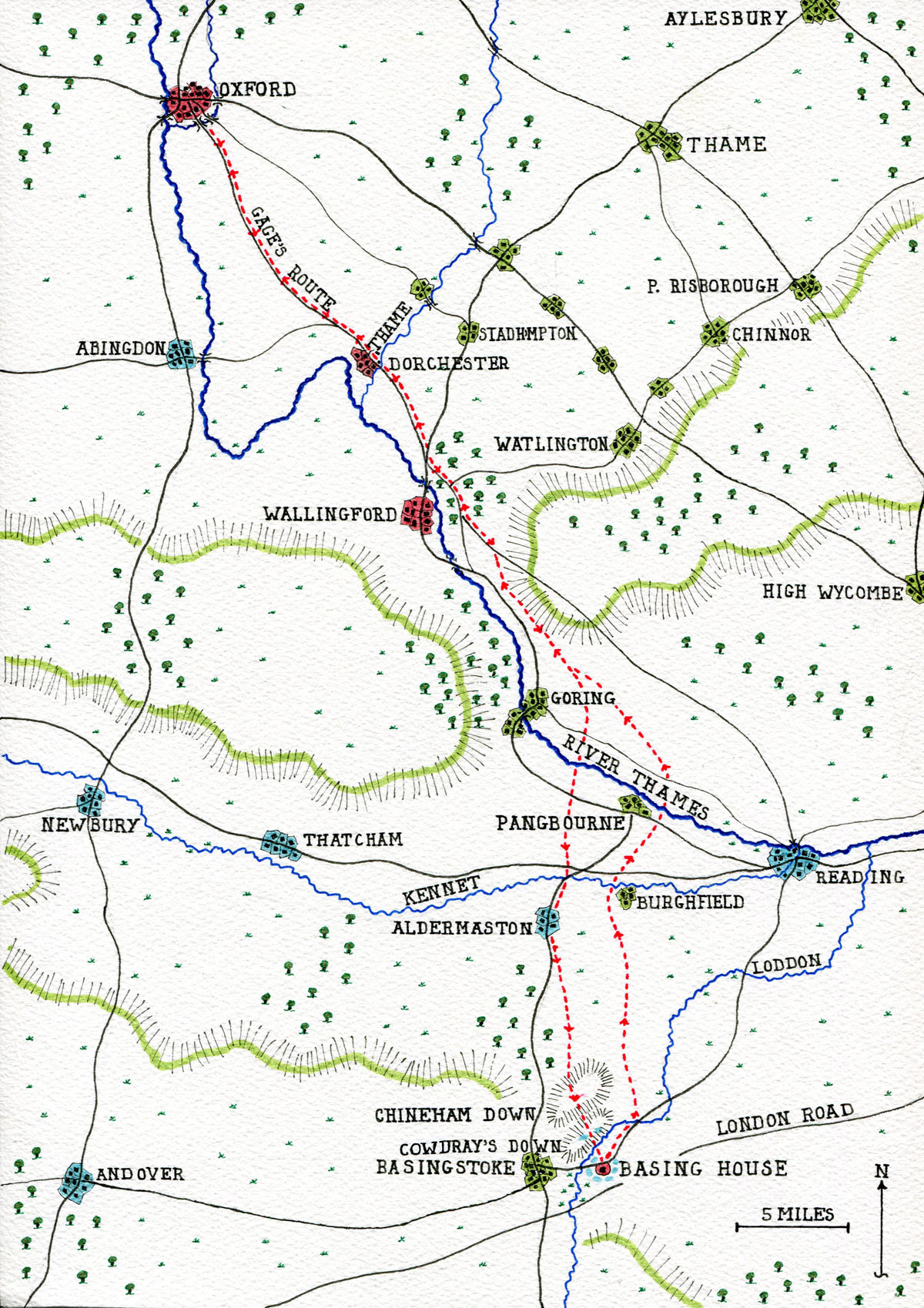

Map of Colonel Gage’s route from Oxford to Basing House on 9th and 10th September 1644 and his return to Oxford on 12th September 1644: Siege of Basing House 1642 to 1645 during the English Civil War: map by John Fawkes

The Marquess of Winchester sent several requests for assistance to Oxford but the view taken by the governor and the council was that the presence of powerful Parliamentary garrisons in Abingdon, Reading and Newbury made it inconceivable that a relief force could march the 40 miles to Basing House and return to Oxford without being discovered and destroyed. There were not the troops in the Oxford garrison to mount a full relief. The best that might be done was to put more supplies into Basing House.

At the beginning of September 1644 the Marchioness of Winchester went to Oxford to seek assistance for her husband’s besieged garrison. The Marchioness possessed powerful connections and she was able to influence the Council particularly as the Marquess wrote to the Council stating that he could only hold out for a further ten days due to the shortage of stores. The sticking point was the refusal of Sir Arthur Aston to release troops from his garrison for any relief column, although Sir William Ogle the governor of Winchester Castle promised 100 Horse and 300 Foot from his garrison to support any attempt to relieve Basing House.

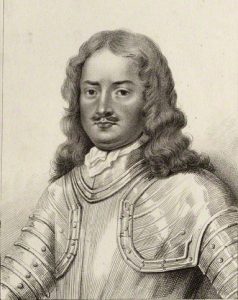

Colonel Henry Gage who mounted two relief columns for Basing House: Siege of Basing House 1642 to 1645 during the English Civil War

With the final plea from the Marquess of Winchester a Catholic officer of the Oxford garrison Colonel Henry Gage proposed a plan. Gage proposed that two Troops of Horse be formed from the entourages of the Nobility and Gentry in Oxford which he would lead to Basing House to effect the relief. The plan depended on the additional assistance from Sir William Ogle in Winchester Castle.

The necessary volunteers were forthcoming for the Horse. A body of Foot was formed from the garrison of Greenlands, a house on the Thames near Henley recently surrendered to Parliamentary troops whose Royalist troops had been permitted to depart to Oxford. The Greenlands garrison provided 400 Foot from Colonel Hawkins’ regiment.

The column carried twelve barrels of gun powder and a quantity of match for the Basing House garrison.

Colonel Gage’s column left Oxford at 10pm on Monday 9th September 1644, moving after dark to reduce the likelihood of their mission being disclosed. Every man wore the orange tawny armband of the Parliamentary forces.

Colonel Gage was accompanied by his Catholic chaplain Peter Wright who had served as Gage’s chaplain when he was in the Spanish service in the Low Countries.

The column’s first stop was at dawn in a wood near Wallingford where the governor of Wallingford added 50 Horse and 50 musketeers commanded by Captain Walters to Gage’s force and the troops rested for a couple of hours.

At this point a courier was dispatched to Winchester Castle calling on the offered assistance from Sir William Ogle. Gage’s plan was that the Winchester Castle troops would attack the besiegers from the south while Gage attacked from the north and the garrison sallied out from Basing House.

During Tuesday 10th September 1644 Gage’s force marched down the east bank of the Thames and crossed the river heading south towards Aldermaston. Wherever possible Gage took bye lanes.

Gage stopped short of Aldermaston and sent Captain Walter’s troop of Horse into the town with the quartermasters to obtain supplies for a halt and a period of rest before the final march to Basing House.

Walter’s men became involved in a sharp fight with Parliamentary troops in Aldermaston killing some and capturing six or seven.

Colonel Gage’s relief column enters Basing House by the Garrison Gate of Basing House: Siege of Basing House 1642 to 1645 during the English Civil War

It was probably inevitable that the approach of the Royalist column would be noticed before it reached Basing House and this seems to have been the point of discovery. Walters is criticized for ‘impetuousness’ and forgetting the disguise. With Parliamentary troops in Aldermaston a fight was perhaps inevitable. While the orange scarf ruse might work at a distance a Royalist force was bound to be identified once met face to face.

Instead of spending much of the night in Aldermaston as he intended Gage marched on at around 11pm. The practice was adopted of permitting the Foot to ride in turn with the mounted troopers, or taking them up behind the riders.

Gage’s force arrived at Chineham Down within two miles of Basing House between 4am and 5am on Wednesday 11th September 1644 in the darkness and thick fog.

The Basing House garrison was burning fires on the top of the main gatehouse to guide Gage and inform him of the readiness of the garrison to sally out.

Before the attack could begin a courier from Winchester Castle arrived to inform Gage that the Winchester Castle troops had not marched due to the presence of a large force of Parliamentary Horse on their route. The Oxford force could no longer rely on a diversionary assault across the Park on the far side of Basing House.

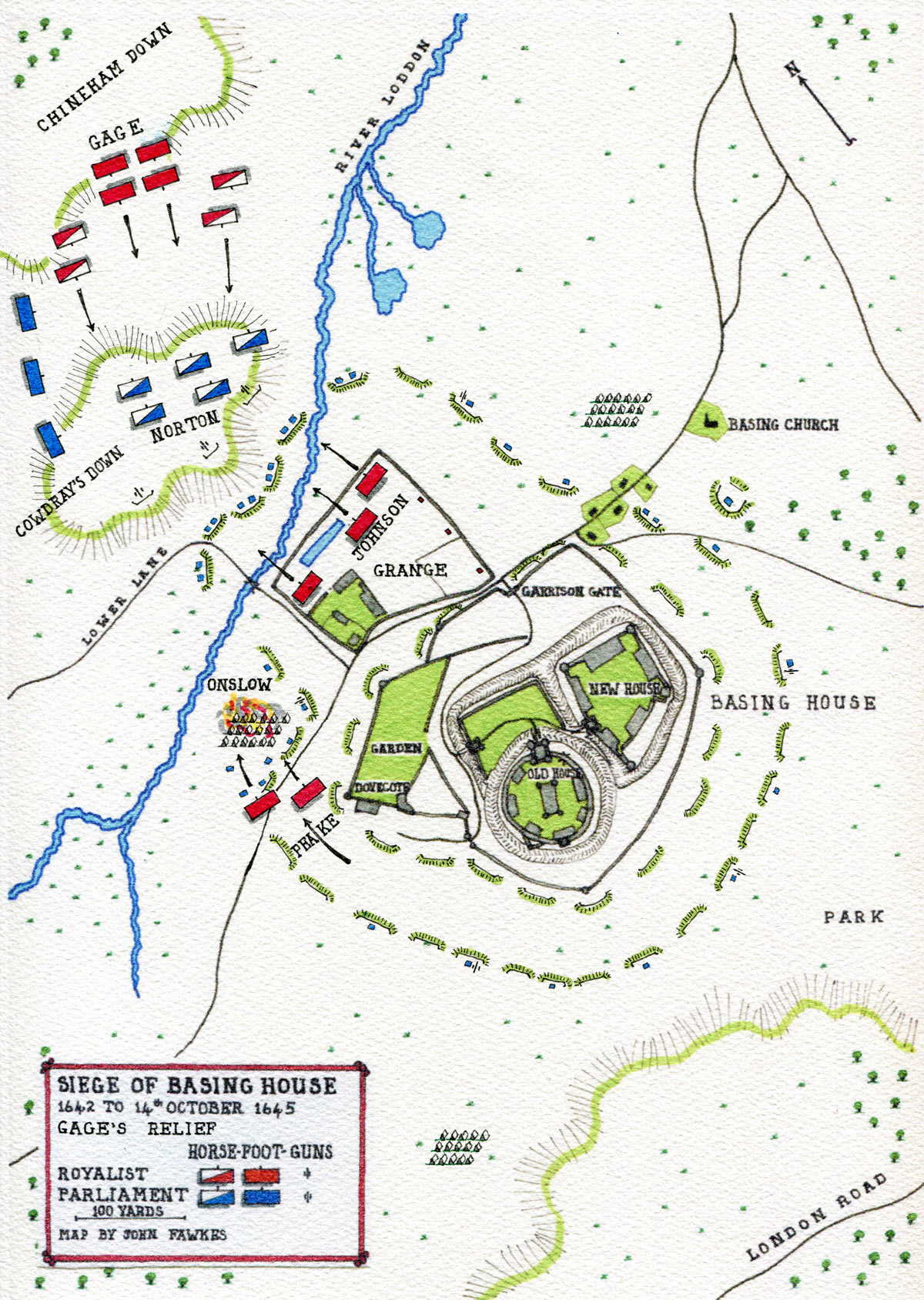

Map of Colonel Gage’s Relief of Basing House on 11th September 1644: Siege of Basing House 1642 to 1645 during the English Civil War: map by John Fawkes: the scale applies to the area of the House alone. Cowdray’s Down and Chineham Down are not in scale

Colonel Gage launched his attack on the Grange, the troops abandoning their orange armbands for Royalist white. His force adopted the conventional battle formation with the Foot in the centre and Horse on each wing. Colonel Webb commanded the right, Lieutenant-Colonel Boncle the left and Gage himself led the Foot in the centre.

Awaiting the Royalist attack was a body of 5 Troops of Horse with musketeers in a position of ambush along a hedge to the right.

The Royalist Horse charged and in spite of a volley from the Parliamentary musketeers routed the Parliamentary Horse while the Royalist Foot saw off the musketeers from the hedge line.

As Gage’s troops pressed on through the fog they sounded their trumpets and beat their drums to warn the Basing House garrison of their approach.

In answer Lieutenant-Colonel Johnson sallied out of the Grange with a body of musketeers and attacked the Parliamentary siege works at the base of Cowdray’s Down quickly driving off the garrison while the Oxford men swarmed in from the far side and entered Basing House through the Garrison Gate.

Colonel Gage wasted no time. He briefly paid his respects to the Marquess of Winchester, transferred 100 men from Colonel Hawkins’ Regiment to the Basing House garrison and handed over the quantity of powder and match brought from Oxford.

Gage then took his men off to Basingstoke Town, a distance of a mile. It was the early hours of market day in Basingstoke. The few Parliamentary officials and soldiers in the town escaped as the Royalists marched in.

The Royalists commandeered 100 head of cattle, many sheep and some 40 pigs. These animals were driven off to Basing House while Gage’s men spent the rest of the day rounding up supplies of wheat, malt, salt, oats, bacon, cheese and butter and dispatching them to Basing House as fast as horses and carts could be found. In addition 12 barrels of gunpowder came to light and were sent on to Basing House.

While Colonel Gage was looting the supplies of Basingstoke Major Cufaud from Basing House and Captain Hull from the Oxford force each with 100 musketeers attacked the Parliamentary troops in Basing Village.

Cafaude and Hull captured Basing Church taking prisoner Captains Jervoise and John Jephson with some 33 other men, the rest of the Parliamentary troops in the village escaping into a battery in the Park.

Another party from the Basing House garrison led by Lieutenant-Colonel Robert Peake attacked Sir Richard Onslow’s Sussex Companies’ quarters in Slaughter Close to the west of Basing House. Peake’s men drove off the Surrey Parliamentarians, destroyed a number of sconces or small redoubts and captured a gun. They left after setting fire to Onslow’s camp.

These attacks around Basing House ensured that Colonel Norton’s Parliamentary force was unable to interfere with the day-long transfer of supplies from Basingstoke to Basing House.

Following the uproar created by Colonel Gage and the Basing House garrison Parliamentarian forces gathered along the route from Basing House to Oxford to prevent Gage’s men from making the return journey.

Aldermaston and Thatcham were occupied by Parliamentary troops and the crossing points across the Thames heavily guarded and in places the bridges were destroyed.

Colonel Norton waited for a sign that Gage’s men were leaving the safety of Basing House to follow and attack them in the rear.

Again Colonel Gage showed his resource and grasp of military operations. Several neighbouring villages were sent demands for further supplies to be delivered to Basing House by noon the next day on pain of Gage’s troops visiting and burning the villages to the ground. These demands were passed to the Parliamentary authorities leading them to believe that Gage was not yet ready to leave Basing House.

However on the night of Thursday 12th September 1644 under cover of darkness and fog and with no sound from trumpet or drum Colonel Gage’s column marched out for Oxford accompanied by two guides provided from the Basing House garrison.

The Royalist troops wore their ‘orange-tawny’ arm bands again. When challenged they identified themselves as Parliamentary troops taking part in the operation to intercept the Royalist column heading for Oxford.

The route was again via bye ways avoiding towns and villages. Gage’s men crossed the Kennet River by a ford near Burghfield some 5 miles to the east of Aldermaston. They then crossed the Thames at Pangbourne swimming their horses over the river with the foot soldiers taken up on their saddles. Gage’s force reached Wallingford at 8am on Friday 13th September and Oxford the next day.

Colonel Henry Gage received a knighthood from King Charles I for the Basing House exploit.

Continuation of the Second Attack on Basing House:

Following the successful incursion by Colonel Gage the garrison of Basing House continued to hold Basing Church and village with a garrison of 100 musketeers commanded by Captain Fletcher. After an initial surprise attack led by Colonel Norton that was beaten off, the Parliamentarian troops by 23rd September 1644 were back in control of the Church and village.

A serious loss to the garrison was the death following a bullet wound in the shoulder on 14th September 1644 of Lieutenant Colonel Thomas Johnson, in his pre-Civil War profession a well-known physician and herbalist.

During October 1644 the garrison and besiegers of Basing House fought many skirmishes without the situation changing.

In the same month King Charles I marched across Wiltshire, Hampshire and into Berkshire with his Royalist army, fresh from his success at the Battle of Lostwithiel. The King’s intention was in part to relieve the besieged garrisons of Donnington Castle and Basing House.

The Royalist army reached Newbury and there fought the Second Battle of Newbury on 27th October 1644 against the significantly stronger combined armies of Sir William Waller, the Earl of Manchester and the Earl of Essex.

The battle was considered a draw although the King’s army withdrew to Oxford while the King himself rode west with Prince Rupert, before making a further advance on Donnington Castle.

There was no opportunity to relieve Basing House. Nevertheless the King was resolved to make a further attempt to resupply the garrison.

On 18th November 1644 Colonel Gage led a force of 1,000 Horse towards Basing House, each man carrying a bag of provisions for the beleaguered garrison.

The Parliamentary besiegers were by this time in a poor way. Colonel Norton’s force was reduced from 2,000 to 700 by desertion, disease and battle casualties. The spirit had gone out of those men that were left. There was no confidence that Basing House would be taken. The news of the approach of Colonel Gage’s column was the last straw. The Parliamentary troops packed up and left Basing House for Odiham on 19th November 1644.

Colonel Henry Gage’s second relief of Basing House: Siege of Basing House 1642 to 1645 during the English Civil War: picture by Palamades Palamadesz

On 20th November 1644 Gage’s column marched into Basing House to find a garrison near to starvation and almost out of ammunition. Gage stayed for three days before returning to Oxford leaving Basing House re-supplied and equipped with ammunition against further attack. In fact the Parliamentary troops had abandoned the second attempt to take Basing House.

The Marquess of Winchester attributed the deliverance of Basing House to divine intervention.

The Third and Final Attack on Basing House:

Over the winter of 1644/5 the garrison of Basing House prepared for the coming campaigning season with repairs to the fabric, the building of defences and the levelling of the siege works raised by Colonel Norton’s Parliamentary troops.

Re-deployment of the non-Catholic soldiers from Basing House:

The Marquess of Winchester then took a step that was to have devastating consequences for Basing House. The Marquess petitioned the Privy Council, the advisory body to King Charles I in Oxford to withdraw all non-Catholic soldiers from the garrison of Basing House.

The petition does not set out the Marquess’s reasons for this request. It is likely there was friction between the Catholic and non-Catholic soldiery and suspicions of Parliamentary spies among the non-Catholics.

The petition was acceded to and Colonel Rawdon was ordered to leave Basing House with the non-Catholic soldiers and march to join Lord Goring in the west country.

The Basing House garrison was at a blow reduced significantly without sufficient numbers of Catholic soldiers being available to restore it to the level needed.

The crisis that caused the Marquess to take this destructive step must have been severe indeed. One consequence of this action was to confirm the Parliamentary propaganda that Basing House was a ‘nest of papists’ inflaming the prejudices of its attackers.

Although their forces had retreated in late 1644 there was still a determination on the part of the Parliamentary authorities to destroy Basing House.

Heavy guns of the English Civil War: Siege of Basing House 1642 to 1645 during the English Civil War

On 14th June 1645 the King’s Oxford Army was destroyed at the Battle of Naseby by Sir Robert Fairfax and Oliver Cromwell leading Parliament’s New Model Army.

In August 1645 Parliamentary forces moved again against Basing House. Colonel John Dalbier an experienced officer of French or German origins was given the task of conducting the attack with troops from the Parliamentary garrison at Portsmouth.

Dalbier arrived before Basing House with 800 Horse and Foot on 20th August 1645. More troops arrived from London and Reading giving Dalbier 1,000 Foot and 2 troops of Horse. This was insufficient to conduct a full blockade but enough to begin the siege operations particularly in the light of the much reduced garrison.

Over the following weeks the Royalists commented on the lack of activity of the Parliamentary force. Dalbier was conducting a methodical survey of the structure of Basing House and identifying where breaches could be made to ensure the house was successfully stormed. In due course Dalbier’s batteries were in place, initially on the south side of Basing House and later on Cowdray’s Down, and opened fire.

The effects of the bombardment were quickly felt. A tower in the Old House collapsed on 22nd September 1645 (the tower is marked as ‘C’ in the etching of Basing House by Wencelaus Hollar). The gun fire was switched to the New House and the corner turret brought down with a long stretch of the wall exposing the inside of rooms, with beds and bedding falling into the court.

Dalbier was a resourceful and experienced officer. The Parliamentary troops made piles of straw impregnated with sulphur and arsenic and set fire to them filling Basing House with a noisome smoke.

In the meantime Lieutenant-General Oliver Cromwell, following the Royalist collapse after the Battle of Naseby, was marching across the South of England reducing outstanding Royalist strongholds.

On Monday 6th October 1645 Sir William Ogle surrendered Winchester Castle after a bombardment. Having destroyed the castle Cromwell moved on towards his next target Basing House.

Cromwell arrived before Basing House on 8th October 1645 with an army comprising regiments from the New Model Army: his own, Fleetwood’s, Pickering’s, Montague’s and Hardress Waller’s regiments of Foot, around 5,000 men.

Cromwell’s artillery which he now deployed against the south-east corner of Basing House opposite the New House comprised ‘great guns’ of the heaviest metal, including a cannon royal firing a 63 pound shot and two demi-cannon firing 27 pound shot.

In three days Cromwell’s guns were in batteries ready to open fire along with Dalbier’s guns. Before beginning the bombardment Cromwell sent the Marquess of Winchester a final demand for the surrender of Basing House. The demand made it clear that in the event that Basing House had to be stormed the garrison which Cromwell described as a ‘Nest of Romanists’ could expect no mercy.

Oliver Cromwell interviewing a Royalist prisoner: Siege of Basing House 1642 to 1645 during the English Civil War

This was largely in line with the Conventions of War of the time which permitted attackers of a city or fortified place that rejected a summons to surrender to give no quarter once the place was stormed. The Marquess rejected the demand.

The Fleur de Lys Inn in Basingstoke quarters to Oliver Cromwell the night before the final assault on Basing House on 14th October 1645: Siege of Basing House during the English Civil War

The final bombardment began on Sunday 12th October 1645.

On Monday 13th October 1645 a dark misty morning a party of Horse stole out of Basing House and captured two senior Parliamentary officers, Colonel Hammond and Major King, who were riding around the house to visit Cromwell.

Offers to exchange Hammond and King were rejected by the Marquess causing Cromwell to threaten that if either was harmed the Marquess himself would suffer.

By the end of 13th October 1645 two good breaches had been made in the walls of Basing House sufficient to permit the entry of storming parties. Cromwell resolved to storm Basing House the next morning. He spent the rest of that night at his headquarters in the Fleur de Lys Inn in Basingstoke in prayer while his subordinates organized the storming parties.

Map of the Final Storming of Basing House on 14th October 1645: Siege of Basing House 1642 to 1645 during the English Civil War: map by John Fawkes

Final Storming of Basing House

At 6am on 14th October 1645 the signal for the attack was given: four guns fired in quick succession.

Colonel Dalbier led his men against the side of the Grange by what had become known as the ‘Bloody Barn’ (also the ‘Great Barn). Cromwell’s New Model Army regiments attacked across the lane and into the compound. The cry was ‘for God and Parliament’.

The house with its garrison down to around 200 men was under assault by 7,000 Parliamentary troops who were over the walls and in through the breaches within minutes. The garrison fought with muskets, short pikes, swords and hand grenades thrown from the windows and over the walls.

In addition to storming the breaches the attackers once up to the buildings entered through the windows using scaling ladders to reach the upper floors.

The inside of the Postern Gate on the north-west front of the Old House through which Parliamentary troops stormed into Basing Hose on 14th October 1645: Siege of Basing House 1642 to 1645 during the English Civil War

One party forced its way in through the postern in the basement of the Old House. Others stormed the Great Gate of the Old House.

Once inside the fighting dissolved into hand to hand struggles down the corridors and in the rooms, interspersed with looting the substantial amount of wealth in the house. The cry of the Parliamentary soldiers was ‘Down with the Papists’.

A store of gunpowder detonated destroying sections of the New House and killing members of the garrison and attackers alike. The word went round that the explosion was a deliberate trap by the defenders further inflaming the maddened Parliamentary solders.

The Marquess of Winchester surrendered himself to his prisoner Colonel Hammond who attempted to defend him but could not prevent the Marquess from being stripped of much of his clothing.

The Looting of Basing House: Siege of Basing House 1642 to 1645 during the English Civil War: picture by Landseer

The rich clothing of the noble and gentle women found in Basing House was looted leaving many in their underclothes or largely naked.

As the defence collapsed members of the garrison escaped over the wall and made off. Major Cufaud was one of these but was shot from the ramparts.

Major Robinson attempted to surrender to Major Thomas Harrison a fanatical Puritan who simply shot him dead.

As the fighting subsided the few prisoners to survive were locked in the basement and the Old and New Houses thoroughly looted.

During his extensive bombardment the implacable Colonel Dalbier used ‘red-hot shot’ heated in ovens in the batteries. As the fighting died down one of Dalbier’s ‘red-hot shot’ ignited the woodwork in which it was embedded and the New House took fire. It burned for twenty hours while the Parliamentary troops and the inhabitants of the neighbourhood looked on. All the Royalist soldiers imprisoned in the basement were burned.

The Defence of Basing House: Siege of Basing House 1642 to 1645 during the English Civil War: picture by Charles West Cope

Casualties at the Siege of Basing House:

In the final attack it is said the Parliamentary casualties were 40.

6 Catholic priests were found in Basing House and ‘put to the sword’ during the final attack.

Other than those who escaped over the walls the entire garrison of Basing House was lost, probably around 200 men, including Majors Robinson and Cufaud and Captain Wiborn.

The killing of Dr Griffith’s daughter as she attempted to defend her father during the final storm of Basing House 14th October 1645: Siege of Basing House 1642 to 1645 during the English Civil War

The daughter of the Reverend Dr Griffith, the Rector of St Mary Magdalene in London attempted to defend her father, seriously wounded and taken prisoner. The daughter abused her father’s captors calling them ‘Roundheads and traitors’. They killed her and stripped her body naked.

Follow-up to the Siege of Basing House:

Colonel Hammond and Oliver Cromwell’s chaplain reported the capture of Basing House to Parliament. Cromwell recommended that an example be made of Basing House by destroying the building completely.

The sketch for Cope’s picture ‘the Defence of Basing House’: Siege of Basing House 1642 to 1645 during the English Civil War

On 15th October 1645 the House of Commons ‘Resolved, that the house, garrison and walls at Basing House be forthwith totally slighted and demolished. Resolved that whosoever will fetch away any stone brick or other materials of Basing House shall have the same for his or their pains.’

Many local inhabitants took away bricks and other materials from the ruins of the Old and New Houses of Basing House to build cottages, some still in existence.

Oliver Cromwell was awarded a pension of £2,500 a year by Parliament following his successes. The pension was paid from the sequestrated estate of the Marquess of Winchester.

Following his capture in the Storming of Basing House the 5th Marquess of Winchester was imprisoned in the Tower of London on a charge of treason. Initially the Marquess was among those excluded from the general amnesty for Royalist supporters proposed by Parliament but in 1648 he was released on bail and in 1649 the proceedings against him were discontinued. The sequestration of the Marquess’s estates was abandoned and on the Restoration he received back those parts of his estate that had been taken.

The Marquess of Winchester lived at his estate at Englefield House to the south-west of Reading in Berkshire until his death on 5th March 1674.

Basing House has not been rebuilt.

Personalities, anecdotes and traditions from the Siege of Basing House:

- The defence works for Basing House were dug by local labour as the soldiers of the garrison refused to do digging work without additional pay.

- The River Loddon was dammed by the Basing House garrison to make the ground to the north of Basing House marshier than it already was.

- The walled garden on the west side of Basing House was used to grow vegetables and keep chickens, pigs and the garrison’s horses during the Siege of Basing House between 1642 and 1645. Lieutenant-Colonel Thomas Johnson, a well-known London Apothecary before the Civil War and senior officer in the Basing House garrison established a ‘Physick Garden’ in the walled garden to grow medicinal herbs for treating the many sick and wounded members of the Basing House garrison.

- Charles West Cope’s picture ‘the Defence of Basing House’ was painted as a fresco in the Houses of Parliament in 1862. The preliminary sketch for ‘the Defence of Basing House’ did not highlight the Catholic character of the garrison. This was remedied in the final work (see above).

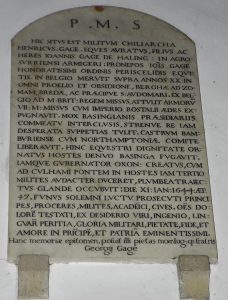

- Colonel Sir Henry Gage (29 August 1597 – 11 January 1645) was born in Haling, Surrey (now incorporated into South Croydon). Gage from a staunchly Catholic family was educated in Flanders for the Church but enlisted in the Spanish army and fought extensively in the Low Countries, taking a prominent part in breaking the Siege of St Omer. Gage published an English translation of an account of the Siege of Breda originally written in Latin. Clarendon described Gage as “a man of great wisdom and temper, and one among the very few soldiers who made himself universally loved and esteemed“. Gage was knighted for the relief of Basing House and his other exploits: returning to England with arms and equipment for the King’s troops, capturing Boarstall House and relieving Banbury Castle with the Earl of Northampton. Gage was appointed Governor of Oxford. On 11th January 1645 in response to the execution of Archbishop William Laud the previous day the King launched an attack on the Parliamentary garrison in Abingdon. Sir Henry Gage led the assault and was killed on Culham Bridge. Gage a pious Catholic attending Mass daily was accompanied in Flanders and in England by his chaplain the Jesuit Peter Wright. Sir Henry Gage funeral in Christ Church Cathedral Oxford was attended by members of the Royal Family. Gage’s memorial is in the Lucy Chapel with several other Royalist Civil War memorials.

- Translation of the text on the memorial to Colonel Sir Henry Gage: ‘Here lies the senior army officer Henry Gage, gilded knight, son and heir of John Gage Gentleman of Haling in the county of Surrey, great-grandson of John Gage of the most noble order of Knights of the Garter. He served in Belgium for more than twenty years in all the battles and the sieges of Bergen op Zoom, Breda and principally Saint Omer. Sent from Belgium he brought to Great Britain weapons for seven thousand men. Given a command he took Boarstall House by storm. Soon when the garrison of Basing House was cut off from supplies, he showed great energy and, when hope had already been abandoned, brought them provisions. Together with the Earl of Northampton he relieved the garrison of Banbury. He was knighted for this and subsequently for the second time drove the enemy from Basing House. He was now made Governor of Oxford. But in an action near the bridge at Culham, while boldly leading his men in the third assault on the enemy, he was struck by a bullet and killed on the 11th of January 1644 [the year should be 1645]

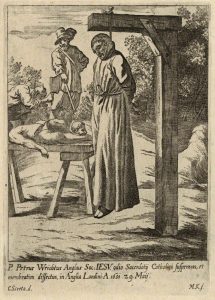

The hanging, drawing and quartering of the Blessed Peter Wright in 1651 at Tyburn: Siege of Basing House 1642 to 1645 during the English Civil War

at the age of 47. In solemn mourning his funeral was attended by members of the Royal Family, Noblemen, Soldiers, Members of the University and Citizens all showing their grief at the loss of a man outstanding for his natural genius, skill in languages, military ability, sense of duty, loyalty and love for his King and country. This brief memorial was installed by his sorrowing and grieving brother George Gage.

- The Jesuit Priest Peter Wright was present when Sir Henry Gage was shot in the attack on Abingdon on 11th January 1645 and gave him the last rites. Peter Wright subsequently became chaplain to the Marquess of Winchester, possibly in Basing House. In 1651 Father Wright was arrested by pursuivants at the Marquess’s London house and convicted of being a Catholic priest on the testimony of Sir Henry Gage’s brother Thomas Gage, an ex-Dominican priest. Peter Wright was hanged, drawn and quartered at Tyburn. Peter Wright was beatified in 1929.

- The several dispatches from the Marquess of Winchester to the King’s Council in Oxford during the course of the Siege of Basing House between 1642 and 1645 were carried by Edward Jeffrey. Jeffrey knew the area well. He would steal out of Basing House take a horse from the Parliamentary lines and ride the 40 miles to Oxford crossing the River Thames on the way, later returning to Basing House with letters for the Marquess.

- Marmaduke Rawdon, the commander of the Basing House garrison for much of the English Civil War was before the war a successful City of London merchant and lieutenant-colonel in the London Trained Bands. With the outbreak of the Civil War Rawdon said farewell to his wife whom he did not see again and left for Oxford where King Charles I made him a colonel in the Royalist army. Rawdon raised a regiment of musketeers which became the core of the Basing House garrison until 1645 when the Marquess of Winchester caused the non-Catholic troops of the garrison to be ‘redeployed’. Rawdon was knighted by King Charles I at Oxford on 28th December 1643. Rawdon on leaving Basing House was appointed governor of Faringdon in West Oxfordshire. Rawdon died of pneumonia while the town was under siege on 28th April 1646 and was buried in Faringdon Church.

- Robert Peake, the deputy commander of the Basing House garrison and the commander after the non-Catholic troops were sent away from Basing House in March 1645 was the grandson of King James I’s ‘serjeant-painter’. Peake was a print publisher with a shop in Holborn until the English Civil War broke out when he was commissioned into Colonel Rawdon’s regiment and went to Basing House as a senior officer in the garrison in 1643. Peake was knighted by King Charles I at Oxford on 27th March 1645 for his services at Basing House. Peake was made prisoner on the storming of Basing House on 14th

Thomas Johnson eminent herbalist and lieutenant-colonel in the Basing House garrison fatally wounded on 14th September 1744: Siege of Basing House 1642 to 1645 during the English Civil War: engraving by Robert Wright

October 1645. He was detained in Winchester House and the Aldersgate in London and after refusing to take the oath of allegiance to Cromwell was banished. After the Restoration Peake was appointed Vice-President and Leader of the Honourable Artillery Company dying in 1667 in his 70s. Peake published work by William Faithorne another member of the Basing House garrison who subsequently worked for Peake’s son.

- Lieutenant-Colonel Thomas Johnson was a member of the Basing House garrison. Johnson was a herbalist and apothecary in business in Snow Hill in the City of London where he kept a physic garden and was a prominent member of the Apothecaries’ Company. Johnson edited Gerard’s ‘Herball’ adding 800 further species of plant. With the outbreak of the English Civil War Johnson was commissioned as a lieutenant-colonel and joined the Basing House garrison. Johnson was fatally wounded in a skirmish on 14th September 1644. Johnson published a number of works on plants and plant remedies. He was given a degree by the University of Oxford in 1642 and became MD in 1643.

- The architect Inigo Jones was a member of the Basing House garrison and was present when Basing House finally fell on 14th October 1645, leaving the house clad only in a blanket, plundered of his belongings and clothes. At the outbreak of the English Civil War in 1642 Inigo Jones was Surveyor of the King’s Works. Among Inigo Jones’s buildings was the Queen’s Chapel at St James’s Palace for Henrietta Maria, Queen to King Charles I. It seems likely that the King sent Inigo Jones to Basing House in 1643 with the garrison troops to advise on the fortifying of Basing House. It was a cruel irony that one of Inigo Jones’ finest buildings the Whitehall Banqueting Hall was the scene for the execution of his master King Charles I in 1649.

- William Faithorne a member of the garrison of Basing House at the time of the storming on 14th October 1645 was apprenticed to Robert Peake as an engraver. Faithorne accompanied Peake into the service of King Charles I on the outbreak of the English Civil War in 1642 and became a member of the Basing House garrison in 1643. Captured at the Storming of Basing House Faithorne was imprisoned in Aldersgate with Peake. On release Faithorne was banished to France. On his return in 1650 Faithorne opened a shop at Temple Bar where he worked as an engraver and print seller. Faithorne died in 1691.

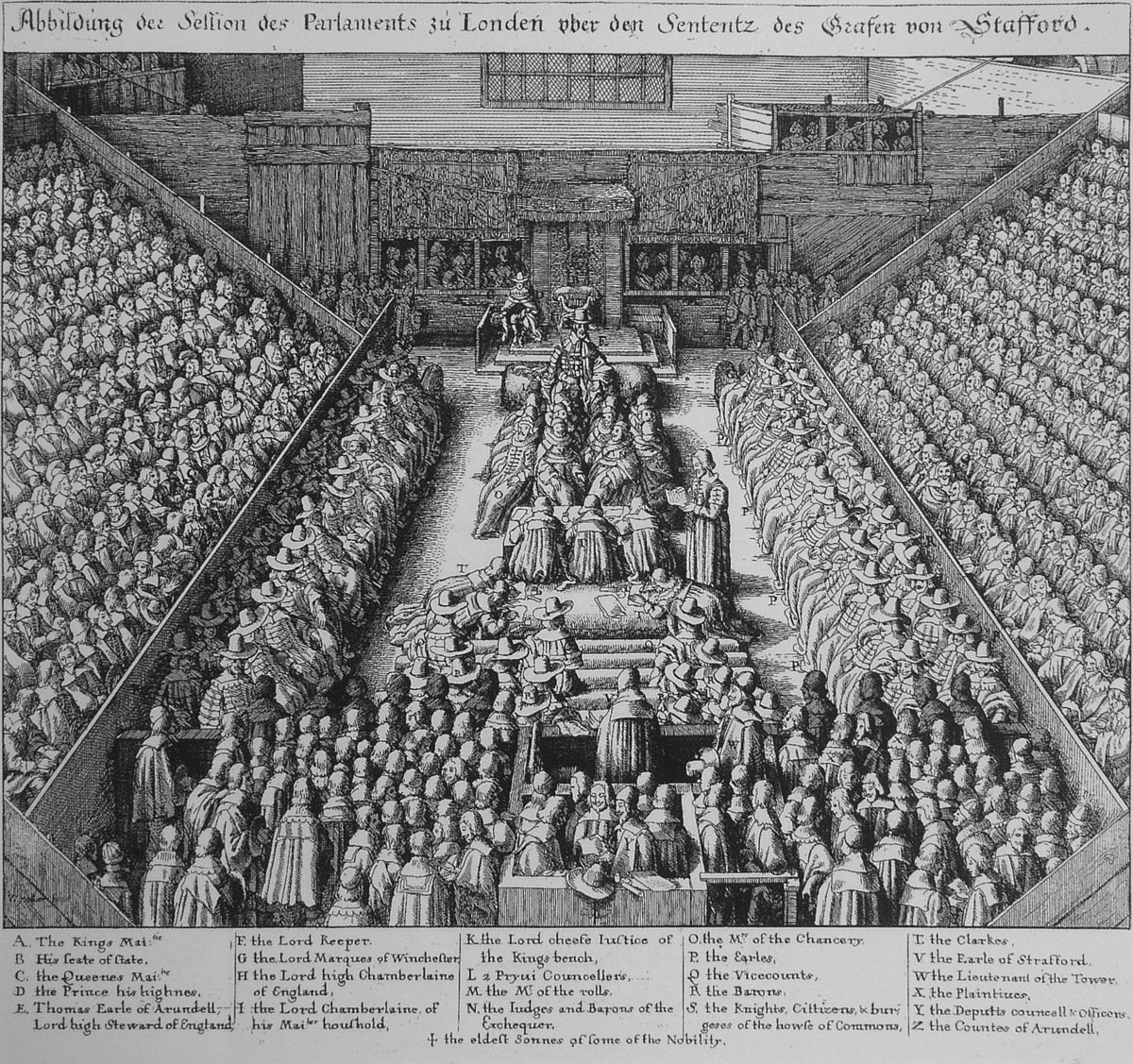

- Wencelaus Hollar the renowned engraver was a member of the Basing House garrison. Hollar was born in Prague and came to England in the employ of the Earl of Arundel in 1637. Hollar was a prolific engraver producing what amounted to a visual record and commentary on contemporary personalities and affairs before and during the English Civil War. Hollar joined King Charles I’s army following the outbreak of war with Robert Peake and William Faithorne and in 1643 became a member of the Basing House garrison. Hollar’s engraving of ‘The Siege of Bazinge House’ (see above) is probably the only reliable contemporary visual record of the House. Hollar was captured following the Storming on 14th October 1645 and imprisoned with Peake and Faithorne. He also went into exile returned in 1652 and lived with Faithorne. He died in poverty in London in 1677.

The Trial of the Earl of Strafford engraved by Wencelaus Hollar member of the Basing House garrison from 1643 to the Storming on 14th October 1645: Siege of Basing House 1642 to 1645 during the English Civil War

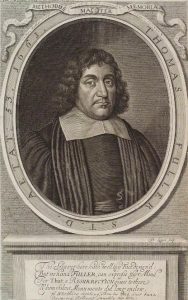

- Thomas Fuller (1608 to 16th August 1661) a prominent clergyman in the Church of England and a prolific and witty author was a member of the Basing House garrison from April 1644 to March 1645. At the beginning of the English Civil War Fuller was a successful writer and preacher in London. Fuller was a member of a Church deputation to the Treaty of Uxbridge in 1643 which lead to his arrest by Parliamentary officers for a brief period. Fuller’s preaching showed his Royalist sympathies and he was forced to leave London for the Royalist capital Oxford in August 1643. Fuller became chaplain in Sir Ralph Hopton’s Regiment and was present at the Battle of Cheriton on 29th March 1644. After the battle Hopton’s army rested at Basing House. Fuller remained at Basing House where he wrote much of his best known work ‘Worthies of England’, an extensive description of the English counties with biographies of their most prominent natives particularly the religious. Fuller left Basing House in 1655 presumably with the departure of the non-Catholic section of the garrison and went to Exeter where he became chaplain to the household of the infant Princess Henrietta Maria. During the Commonwealth Fuller thrived under various patrons as he did after the Restoration. Fuller wrote and preached extensively, particularly in the Savoy Chapel. With the Restoration Fuller was appointed Doctor of Divinity by Cambridge University and Chaplain Extraordinary to King James II. Thomas Fuller died of typhus fever in 1661 in London. He is commemorated by a tablet in Cranford Church where he was Rector.

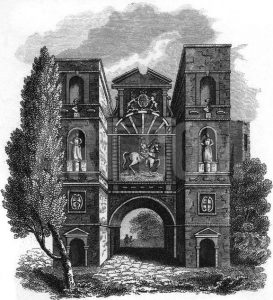

Aldersgate in London where Robert Peake, William Faithorne and Wencelaus Hollar were imprisoned after the Storming of Basing House in 1645: Siege of Basing House 1642 to 1645 during the English Civil War: engraving by Wencelaus Hollar

References for the Siege of Basing House:

Love Loyalty The Close and Perilous Siege of Basing House by Wilf Emberton

Sieges of the Great Civil War by Brigadier Peter Young and Wilfrid Emberton

The King’s War by C.V. Wedgwood

The English Civil War by Peter Young and Richard Holmes

History of the Great Rebellion by Clarendon

Cromwell’s Army by CH Firth

The previous battle of the English Civil War is the Battle of Naseby

The next battle of the English Civil War is the Battle of Dunbar