The Battle of Worcester fought on 3rd September 1651 between the Parliamentary army of Oliver Cromwell and the Royalist and Scottish army of King Charles II; the final battle of the English Civil War

The previous battle of the English Civil War is the Battle of Dunbar

The next battle in the British Battles series is the Battle of Blenheim

To the English Civil War index

War: English Civil War.

Date of the Battle of Worcester: 3rd September 1651

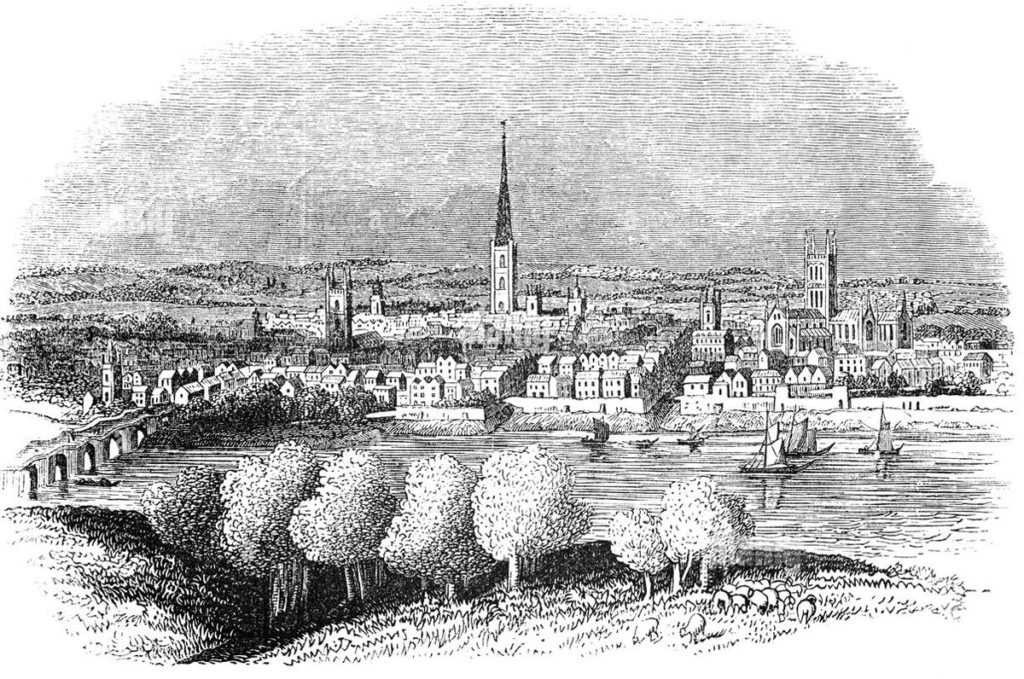

Place of the Battle of Worcester: At and around the City of Worcester in the West of England.

Combatants at the Battle of Worcester: An English Royalist and Scottish Covenanter army against the English Parliamentary army.

Commanders at the Battle of Worcester: King Charles II commanded the Royalist army with Sir David Leslie commanding the Scottish contingent. Oliver Cromwell commanded the Parliamentary army.

Size of the armies at the Battle of Worcester: King Charles II’s army numbered around 16,000 men while the Parliamentary army numbered around 28,000 men.

Uniforms, arms and equipment at the Battle of Worcester: See this section in the Battle of Edgehill.

Winner of the Battle of Worcester: The Royalist and Covenanter army was resoundingly defeated by Cromwell’s Parliamentary army, being nearly annihilated, bringing the English Civil War to a close, with King Charles II’s memorable flight from the battlefield to France.

Events leading to the Battle of Worcester:

Following the Parliamentary victory over the Scottish Covenanter army of Sir David Leslie at the Battle of Dunbar on 3rd June 1650, Leslie withdrew his surviving troops, around 5,000 men, to Stirling while Cromwell occupied Edinburgh and began a siege of Edinburgh Castle.

While his troops assaulted Edinburgh Castle, Cromwell followed Leslie to Stirling, intending to bring him to battle, but found the Scottish position impregnable.

Cromwell withdrew to Edinburgh and completed the subjugation of Edinburgh Castle.

In the meantime, King Charles II assembled a new royalist army, intending to combine it with the reinforced Covenanter army under Leslie.

Cromwell returned to Stirling, manoeuvred around Leslie’s position and began to reduce the country to the north.

By 2nd August 1651 Cromwell was taking the surrender of Perth when he heard that the Royalist/Covenanter army was marching south to invade England.

Cromwell marched out of Edinburgh in pursuit of Charles II’s army on 4th August 1651.

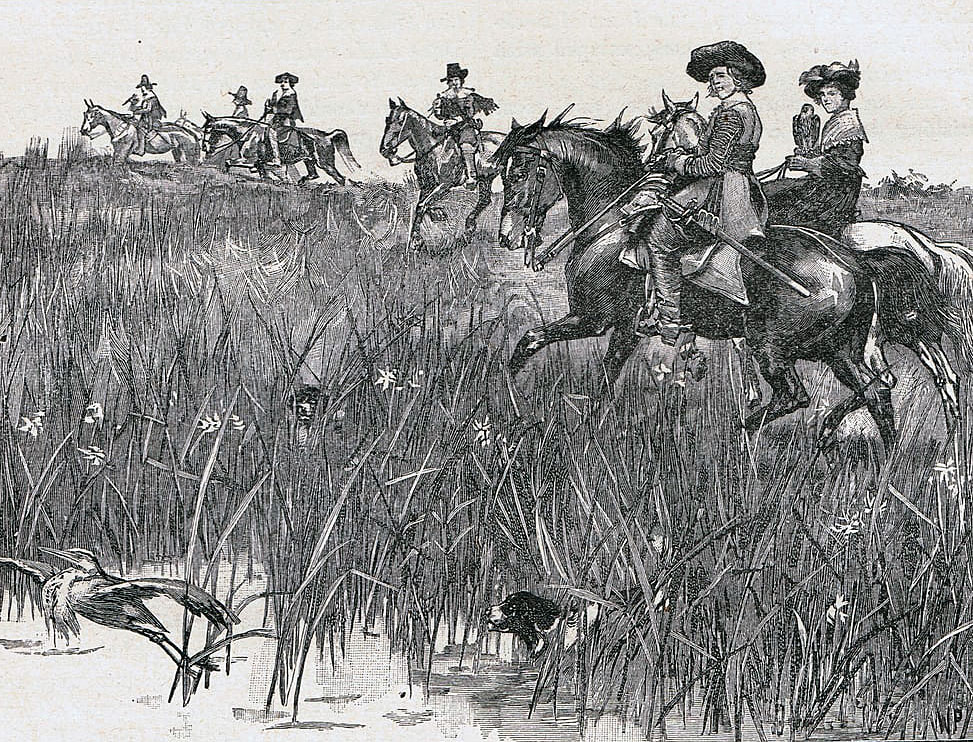

Charles II marched down the west side of England, hoping to attract Royalist recruits. While there was some enthusiasm expressed as he journeyed south, few were prepared to commit themselves by taking up arms.

Generals Lambert and Harrison with a Parliamentary force fought a brief skirmish at Warrington in trying, unsuccessfully, to prevent the Royalist/Covenanter army from crossing the River Mersey.

The Royalist Earl of Derby with a force of some 1,500 men raised in Lancashire and Cheshire was marching to join King Charles II when he was engaged by Colonel Lilburn with 10 troops of horse. Derby was resoundingly defeated, escaping wounded to join the Royalist army with only 30 exhausted horsemen, the survivors of his force.

On 22nd August 1651 Charles II’s army reached Worcester, where it halted, after the gruelling march of some 300 miles from Scotland. Charles prepared to give battle to the pursuing Cromwell.

While the young king had been greeted with enthusiasm by Royalist sympathisers during his march south, few had enlisted in his army, leaving it heavily outnumbered by the gathering forces of Parliament,

Charles hoped during his stay in the city to attract recruits from the approaches to Wales and from the south-west of England.

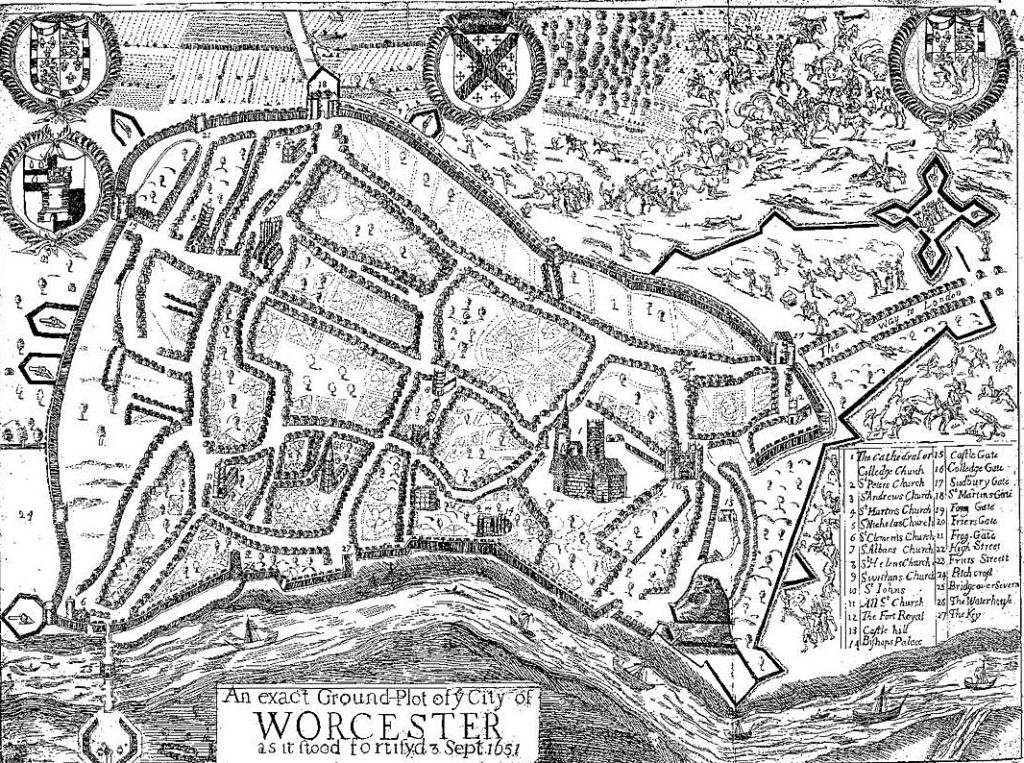

Royalist parties set to work repairing Worcester’s delipidated fortifications and building new defences against the expected attack by Cromwell’s pursuing army, in particular the substantial fieldwork in the north-east of the city known as ‘Fort Royal’.

Cromwell’s marched with his main army into Evesham, some 15 miles from Worcester, on 27th August 1651, where he was joined by several junior commanders, General Fleetwood, Lord Grey of Groby and General Desborough from Reading, giving Cromwell an army of 28,000 men, nearly twice the size of Charles II’s army of 16,000 men.

Charles II conducted a council of war in the afternoon of 29th August 1651 with his subordinate commanders, Sir David Leslie commanding the large Scottish contingent, the Duke of Buckingham and General Middleton among them.

Account of the Battle of Worcester:

The Battle of Worcester began with a Royalist attack on the battery mounted by Cromwell on Red Hill to the east of Worcester which had begun a bombardment of the city and another attack on a fortification being built on the bank of the River Severn.

These attacks were betrayed by a Puritan tailor from Worcester and the 1,500-man Royalist force led by General Middleton and Colonel Keith was repelled with heavy losses.

The tailor was identified and hanged the next day.

The Royalist General Massey was sent with a force of 300 men to defend the crossing of the River Severn at Upton-on-Severn, 9 miles south of Worcester.

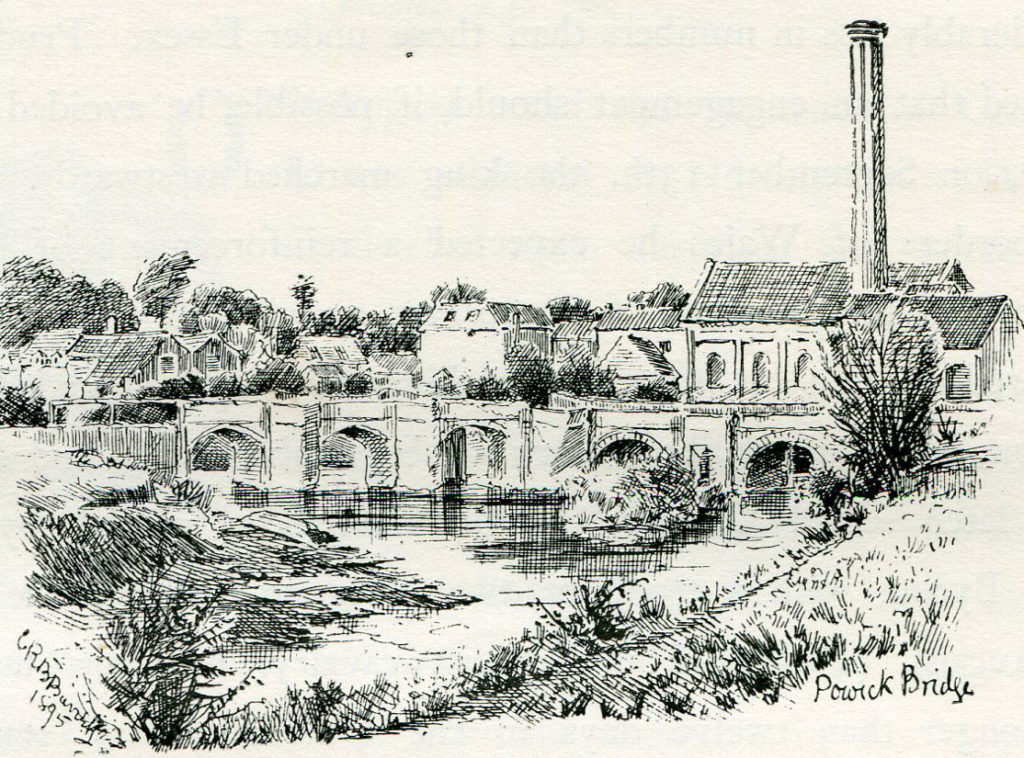

The bridge across the River Severn at Upton was destroyed with a single plank left to provide a crossing for the locals.

During the night of 29th August 1651, the Parliamentary commander, General Lambert, arrived with a force that heavily outnumbered Massey’s, on the east bank of the River Severn opposite Upton with the duty of forcing a crossing. Lambert sent 18 dragoon volunteers to cross the river by the plank.

Massey’s men were unaware of the arrival of the Parliamentary troops and the dragoons were able to cross the broken bridge to the west bank unseen.

The 18 dragoons were identified and attacked, but took shelter in the neighbouring church, where they held out until a large force of Parliamentary dragoons crossed by a ford further down the river and came to their relief.

Massey fought to hold back Lambert’s incursion, but was heavily outnumbered and forced to retreat north towards Worcester, leaving Upton and the crossing point over the River Severn in Lambert’s hands.

The bridge was quickly repaired, enabling the whole of General Fleetwood’s Parliamentary army to cross to the west bank.

As a preliminary to advancing to attack the Royalist army in Worcester, Fleetwood’s army collected sufficient boats to build two floating bridges for the crossing over the Rivers Teme and Severn immediately outside Worcester.

The various elements of the Parliamentary army were ready for the attack on the Royalists in Worcester by 2nd September 1652, but Cromwell directed that the attack be on the following day, 3rd September 1652, the first anniversary of his victory at the Battle of Dunbar.

In the early hours of 3rd September 1652, the Parliamentary troops of Generals Fleetwood and Lambert began their advance north towards Worcester, up the western bank of the River Severn.

The advance was slowed by the need to tow the twenty large boats making up the two bridges of boats to be used in the attack across the River Teme.

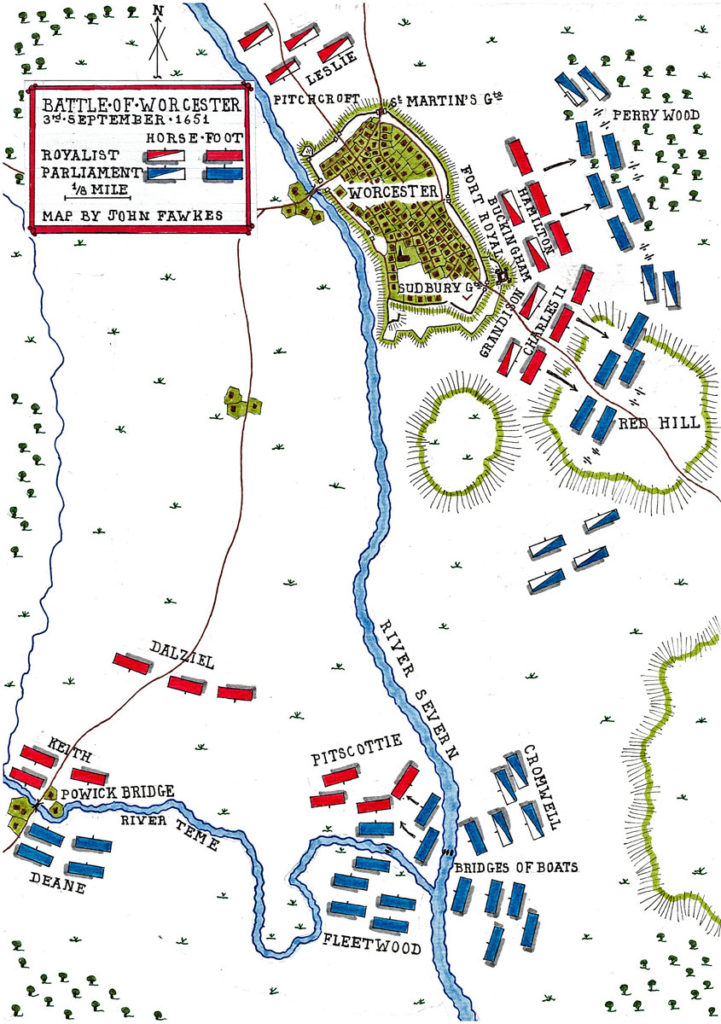

Major-General Robert Montgomery commanded the Royalist troops holding the two-mile line of the River Teme between Powick and the River Severn, comprising the brigades of Colonel Keith, Pitscottie and Major-General Dalziel.

Keith held the bridge across the River Teme at Powick which had been partially destroyed, leaving enough fabric for the locals to cross.

Fleetwood’s and Lambert’s force reached the River Teme in the loop just west of the River Severn and the bridges of boats were put in place in a very short time, one across the River Teme near to its confluence with the River Severn and the other across the River Severn itself just north of the junction of the two rivers.

The Parliamentary guns on Red Hill and in Perry Wood to the east of Worcester on the far side of the River Severn maintained a heavy barrage on the Royalists in the city to divert them from the attack on the far side of the River Severn.

General Deane led the Parliamentary assault on Powick Bridge, but was unable to force his way across.

Lambert’s men crossed the bridge of boats but were driven back by Pitscottie’s highlanders.

King Charles II, at the beginning of the battle watched the fighting along the River Teme, which was described as ‘extremely bitter’, from the tower of Worcester Cathedral.

The King soon took to his horse and rode to the bank of the River Teme to give his personal encouragement to his troops.

Cromwell was also watching the struggle along the River Teme from the high ground on the east bank of the River Severn.

Seeing the difficulties the Parliamentary troops were having in crossing the River Teme and how little progress they were making, Cromwell led three brigades across the second bridge of boats that had, with considerable foresight, been laid across the River Severn with exactly this scenario in mind: the Parliamentary troops on the west bank of the River Severn suddenly requiring urgent reinforcement from Cromwell’s more powerful force on the east bank.

As the second bridge of boats had been moored to the north of the River Teme junction, Cromwell’s three brigades crossed straight onto the ground north of that river, immediately outflanking the Royalists resisting Fleetwood’s troops.

Pitscottie’s Highlanders, fighting Lambert’s men coming over the bridge of boats to their front, were now attacked by Cromwell’s brigades over the River Severn by the other bridge of boats on their left flank.

Facing overwhelming numbers, the Highlanders fell back leaving Keith’s men at Powick Bridge exposed. They retreated in considerable confusion, leaving Keith to be captured.

All the Royalist contingents along the River Teme fell back in disorder, in some cases amounting to rout, to the City of Worcester, crossing by the main city bridge.

While the battle to the west of the River Severn raged for some two hours, King Charles II rode back through Worcester and launched an attack by two columns of Royalist infantry on the Parliamentary right wing.

Charles led the right-hand column against the Parliamentary troops on Red Hill, while the Duke of Hamilton attacked into Perry Wood, the two forces marching out through the Sudbury Gate, covered by the fire from the guns in Fort Royal.

The Parliamentary troops in these positions comprised inexperienced militia and fell back all along the line, under the pressure of the Royalist assault.

The few Parliamentary cavalry still on the east bank of the River Severn hurried to support the line of militia, but they few in number and were pushed back by the Royalist attack.

In considerable haste, Cromwell recrossed the River Severn to the east bank, by way of the bridge of boats, with his three brigades and hurried to the relief of the recoiling militia, turning the tide against the now heavily outnumbered Royalists of King Charles II’s two columns.

The Royalists were driven back through the Sudbury Gate in increasing confusion, all order lost, the soldiers anxious to escape the pursuing Parliamentarians.

King Charles II had fought with considerable courage. He now found his escape blocked by an ammunition waggon, immobilised in the Sudbury Gate. Charles abandoned his armour and squeezed through, finding another horse and joining the Earl of Cleveland, Sir James Hamilton, Colonel Wogan and others in attempting to rally the Royalist troops.

However, the battle was lost. Cromwell’s men were pressing into the city from the east while Fleetwood’s troops crossed the bridge into the city from the south.

Leslie’s Scottish cavalry, supine throughout the battle on Pitchcroft to the north of the city, continued to refuse to take part in the battle.

The Royalist officer, Sir Alexander Forbes, refused to surrender Fort Royal which was stormed and captured by the Essex Militia, who then turned the fort’s guns on the melee in the city.

All the gates of Worcester were now taken by Parliamentary troops, other than St Martin’s Gate leading to the north, where a dreadful slaughter took place of the Royalist soldiers attempting to escape into the countryside.

Lord Rothes, Sir William Hammond and Colonel Drummond continued to resist on Castle Mound in the middle of Worcester until persuaded to surrender on terms by Cromwell himself.

Cleveland and Hammond with a party of Royalist troopers escorted King Charles II out of the city and enabled him to escape the collapse of his army.

Casualties at the Battle of Worcester:

A large proportion of the Royalist army that fought at the Battle of Worcester were Scotsmen from the Covenanting army of Sir David Leslie. 2,000 to 3,000 of them were killed in the battle. 10,000 were captured on the battlefield or as they attempted to escape to Scotland, travelling up through the north of England.

Many of the captured Scottish soldiers died in makeshift prison camps in London, while several hundred were transported to the American colonies to become indentured servants to the colonists, an early form of slavery.

Some 640 Royalist officers became prisoners.

The Duke of Hamilton died of his wounds after the attack on the Red Hill.

The Earl of Derby was captured in Cheshire. He was tried by Parliamentary court-martial and sentenced to death for treason. In spite of a request for clemency lodged by Cromwell himself the Earl was beheaded in Bolton.

General Massey, General Montgomerie and the wounded Sir Alexander Forbes were taken prisoner with the Scottish officers Pitscottie and Keith and the English Lord Grandison.

The Parliamentarians used Worcester Cathedral as a temporary prison for the captured Royalists.

The Parliamentary army is said to have suffered a few hundred casualties.

The senior Scottish generals Leslie and Lauderdale were captured and held prisoner until the Restoration in 1660.

Follow-up to the Battle of Worcester:

After the Battle of Worcester, King Charles II escaped with a small party of senior Royalist officers. After a detour across Worcestershire the King turned west and finally headed for the south coast.

During a stay at Boscobel House King Charles II hid in an oak tree as Parliamentary troops searched the surrounding woods.

The King eventually reached Shoreham on the south coast in Sussex and took ship to France.

The King remained on the Continent until the Restoration in 1660.

The Battle of Worcester ended the Civil War.

After the Battle of Worcester Cromwell sheathed his sword and did not fight again.

Anecdotes and traditions from the Battle of Worcester:

- The day after the Battle of Worcester, Cromwell wrote to the Speaker of the House of Commons saying: ‘The dimensions of this mercy are above my thoughts. It is, for aught I know, a crowning mercy.’

References for the Battle of Worcester:

British Battles by Grant.

History of the British Army by Fortescue Volume 1

Battles in Britain by William Seymour

British Battles by Grant.

The previous battle of the English Civil War is the Battle of Dunbar

The next battle in the British Battles series is the Battle of Blenheim

To the English Civil War index