The decisive defeat and destruction of King Charles I’s Royalist Army by the Parliamentary New Model Army led by Sir Thomas Fairfax, fought in Northamptonshire on 14th June 1645

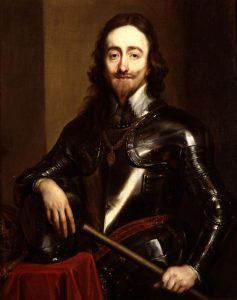

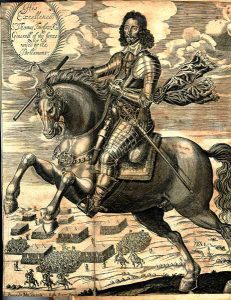

King Charles I and Prince Rupert before the Battle of Naseby 14th June 1645 during the English Civil War

The previous battle in the English Civil War is the Second Battle of Newbury

The next battle in the English Civil War is the Siege of Basing House

To the English Civil War index

Battle: Naseby

War: English Civil War

Date of the Battle of Naseby: 14th June 1645

Place of the Battle of Naseby: In the county of Northamptonshire.

Sir Thomas Fairfax Parliamentary commander at the Battle of Naseby 14th June 1645 during the English Civil War

Combatants at the Battle of Naseby:

The forces of King Charles I against Parliament’s newly formed New Model Army.

Generals at the Battle of Naseby: King Charles I was present although Prince Rupert commanded his Royalist Army.

Sir Thomas Fairfax commanded the New Model Army of Parliament with Oliver Cromwell as his deputy.

Size of the armies at the Battle of Naseby:

The Royalist army comprised around 4,000 Horse and 5,000 Foot. The Parliamentary army comprised around 7,000 Horse and 9,000 Foot. The number of guns in the battle is uncertain but they played a minor part firing probably a single round before the Royalist attack.

Winner of the Battle of Naseby: The Parliamentary New Model Army led by Sir Thomas Fairfax decisively defeated and dispersed the Royalist Army.

Uniforms, arms and equipment at the Battle of Naseby:

See this section in the Battle of Edgehill.

Background to the Battle of Naseby:

The origins of the English Civil War are dealt with under this section in the Battle of Edgehill.

Over the winter of 1644/5 Parliament implemented the idea put forward by Sir William Waller of replacing the various Parliamentary armies in the south of England with the New Model Army.

The preliminary administrative step was the Self-Denying Ordinance whereby Members of Parliament whether in the Commons or the House of Lords lost their military or naval appointments to be replaced by officers chosen for their merit rather than their political influence.

Sir Robert Fairfax was appointed to command the New Model Army. In February 1645 Fairfax came to London to establish the new army and choose its officers, a particular bone of contention with Parliament.

The basis for the New Model Army was the old armies of the Earl of Essex, the Earl of Manchester and Sir William Waller. Numbers were made up by recruiting and pressing men from the counties of the South-East of England.

Sir Marmaduke Langdale commander of the Royalist left wing at the Battle of Naseby 14th June 1645 during the English Civil War

The New Model Army comprised 11 regiments of Horse, each of 600 men, one regiment of Dragoons of 1,000 men and 12 regiments of Foot, each of 1,200 men; 22,000 soldiers in all. The artillery was given a separate establishment, with many of its guns captured from the Royalists. A corps of musketeers was raised to escort the guns, equipped with firelocks as posing less of a fire risk to the ammunition.

There was little time for training the new regiments as the New Model Army took the field in April 1645, Fairfax marching south-west to Taunton while Cromwell campaigned in Oxfordshire to keep the Royalists from advancing on London.

At a meeting on 8th May 1645 at Stow-on-the-Wold the Royalist commanders devised their strategy for the year. King Charles I and Prince Rupert would march north to relieve Chester and then tackle the Scots army besieging Pontefract, the ultimate aim being to make contact with the Earl of Montrose campaigning with great success in Scotland. Lord Goring would take his cavalry force to the west country.

Oliver Cromwell commander of the Parliamentary right wing at the Battle of Naseby 14th June 1645 during the English Civil War

Parliament directed Sir Robert Fairfax to send a brigade to relieve Taunton and to march with the rest of his army to attack Oxford in the absence of the King’s army.

On 19th May 1645 Fairfax arrived to begin a siege of Oxford and was joined by Cromwell. The threat to Oxford seriously alarmed the King. It became his priority to lure Fairfax to the Midlands.

Prince Rupert sent orders to Lord Goring to join his army at Market Harborough, but Goring determined to stay in the west ignored the order.

On 30th May 1645 the King’s army captured and sacked Leicester provoking Parliament to order Sir Robert Fairfax to abandon the siege of Oxford and tackle the Royalists.

Cromwell was detached to cover the eastern counties against any Royalist incursion following the capture of Leicester.

Prince Rupert of the Rhine the Royalist commander at the Battle of Naseby 14th June 1645 during the English Civil War

Fairfax marched north from Oxford on 5th June 1645. Fairfax’s Council of War resolved on giving battle to the King’s army, a course approved by Parliament. The King at Daventry in Northamptonshire was delighted that he was drawing Fairfax’s army into battle, although he did not expect it to move with such expedition.

On 12th June 1645 King Charles I was hunting when he received the surprising news that Fairfax’s army was at Kislingsbury, ten miles from the Royal Camp at Borough Hill to the south-east of Daventry.

The Royal army was reduced by desertion after the storming of Leicester and the detachment of a garrison for the captured town. The failure of Lord Goring to rejoin the army left the Royalist cavalry arm depleted.

On 13th June 1645 Cromwell rejoined Fairfax’s army with his cavalry.

Account of the Battle of Naseby:

As the Parliamentary army assembled the King withdrew north-east towards Market Harborough. Fairfax resolved to follow marching on 13th June 1645 to Guilsborough four miles south of Naseby. At Naseby a Parliamentary patrol surprised and captured a Royalist picket dining outside an inn. Again the Royalists were taken unawares by the speed of the New Model’s advance.

Royalist picket surprised in Naseby on 13th June 1645: Battle of Naseby 14th June 1645 during the English Civil War: picture by William Barnes Wollen

The King was informed of the imminence of the Parliamentary army at midnight and summoned a Council of War in the early hours of 14th June 1645. The policy of withdrawal was abandoned and it was determined to give battle.

Later that morning the Royalist army formed up on a ridge to the south of Market Harborough between the villages of East Farndon and Oxendon. A position in front of the ridge has the name ‘Rupert’s Viewpoint.

The Parliamentary army was by 3am on the road north to Naseby, marching into Naseby by 5am.

Sir Thomas Fairfax at the Battle of Naseby 14th June 1645 during the English Civil War: engraving by Joshua Sprig

Neither side seems to have known the whereabouts of the other at this point, although the New Model was better served by its scoutmaster-generals than were the Royalists. Fairfax wondered whether the Royalists were continuing to withdraw or intending to give battle and the King and Rupert were informed by the Royalist scoutmaster-general that he was unable to find the Parliamentary army and that it appeared to be nowhere at hand.

Both commanders Prince Rupert and Sir Robert Fairfax rode forward with mounted escorts to discover the true position and plan for the forthcoming battle, Prince Rupert presumably from ‘Rupert’s Viewpoint’.

While initially Fairfax intended to occupy the ground at the bottom of the valley on the Naseby to Clipston road, on Cromwell’s suggestion he decided to pull back to the ridge on the Naseby side of the valley to entice Prince Rupert to launch an

uphill cavalry attack against the Parliamentary line.

Prince Rupert seeing the advancing New Model troops resolved to take the Royalist army into the ground alongside the road between Sibbertoft and Naseby, parallel and to the west of the Clipston road to enable him to launch an attack on the Parliamentary left flank.

Before the battle: Battle of Naseby 14th June 1645 during the English Civil War: picture by Richard Beavis

The Royalist army marched through Clipston and turned west towards Sibbertoft before turning south again onto the Naseby road.

To conform to this route and prevent Prince Rupert working around the Parliamentary left flank Sir Thomas Fairfax moved his army to its left so that it straddled the Sibbertoft to Naseby road directly in the Royalist line of advance.

King Charles I at the Battle of Naseby 14th June 1645 during the English Civil War: picture by Henry Marriott Page

Prince Rupert halted the Royalist army and formed it on either side of the Sibbertoft to Naseby road confronting the Parliamentary position at the top of the ridge.

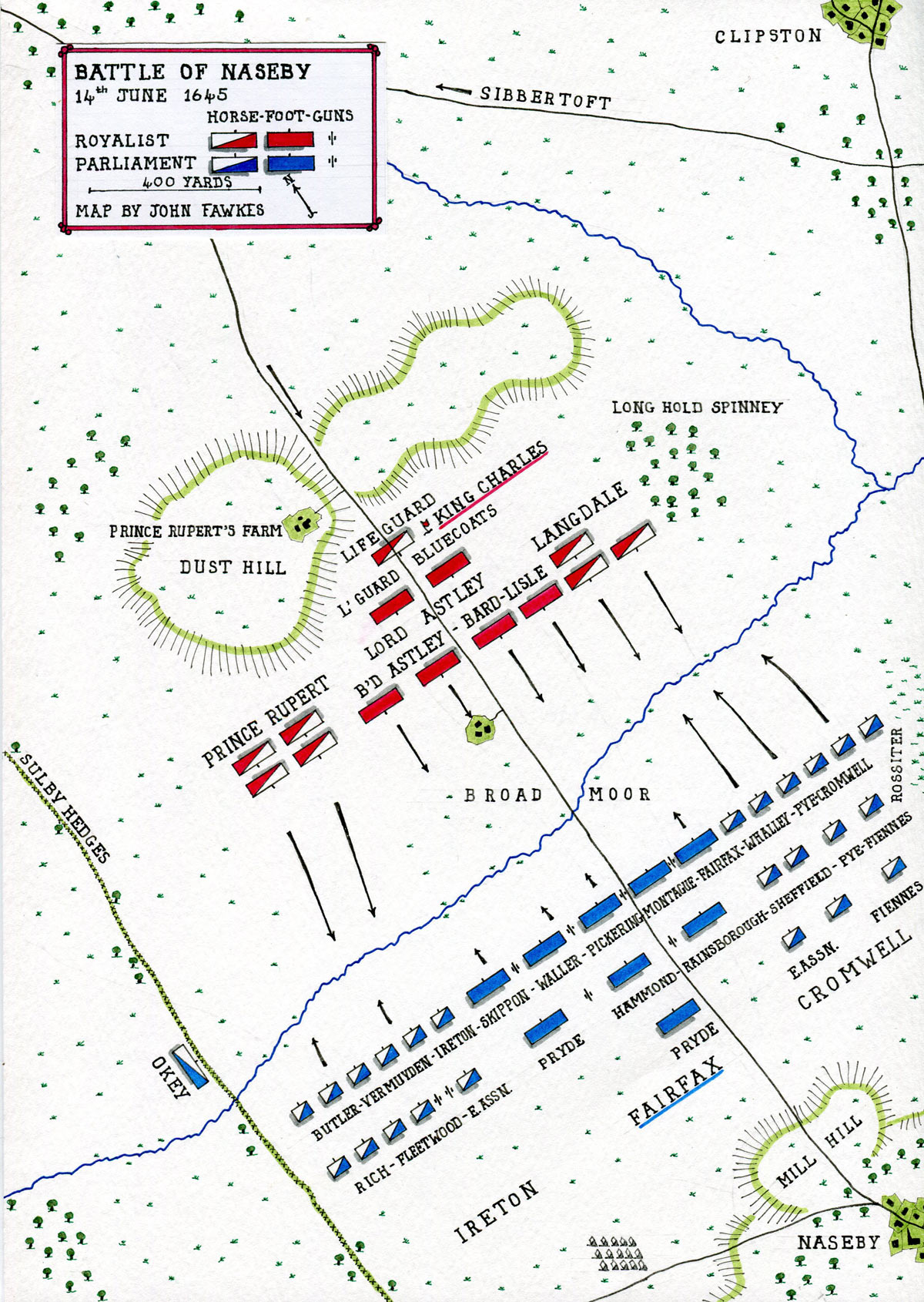

Led forward by King Charles I the Royalist army deployed in the same formation as in its earlier position: on the right immediately to the south of Dust Hill were 2,000 cavalry commanded by Prince Rupert himself; in the centre was the Foot commanded by Lord Astley, supported by 800 Horse commanded by Colonel Thomas Howard; on the Royalist left stood Sir Marmaduke Langdale with his Northern Horse, numbering 1,500. A reserve was formed by the Foot Lifeguard and Prince Rupert’s Bluecoats with the Lifeguard of Horse commanded by Lord Bernard Stuart and the Newark Horse comprising some 900 mounted men. The Royalist left rested on Long Hold Spinney.

The New Model Army of Sir Thomas Fairfax was now drawn up on the ridge with Broad Moor separating it from the Royalist army.

Major-General Philip Skippon, commanding the Parliamentary Foot in the centre of the army formed the front line of five regiments: from the left, Skippon’s, Hardress Waller’s, Pickering’s, Montague’s and Fairfax’s, with three regiments in the second line; from the left, Harley’s commanded by Lieutenant-Colonel Thomas Pryde, Hammond’s and Rainsborough’s. Part of Harley’s regiment formed a third line as a reserve.

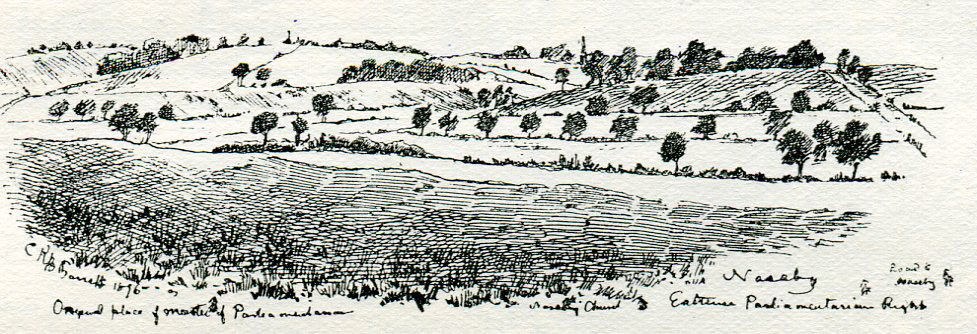

Battlefield of the Battle of Naseby 14th June 1645 during the English Civil War: drawing by C.R.B. Barrett

On the Parliamentary right stood a wing of Horse commanded by Oliver Cromwell, with Cromwell’s, Pye’s and Whalley’s in the first line; Fiennes’, Pye’s and Sheffield’s in the second line and Fiennes’ and the Eastern Association Horse in the third line. Rossiter’s Horse took up a position in the right of the wing due to its late arrival.

The King’s Horse move into position to charge at the Battle of Naseby 14th June 1645 during the English Civil War: picture by Sir John Gilbert

There was difficult broken ground on the right of the Parliamentary army which compressed Cromwell’s wing so that the regiments were deeper than intended.

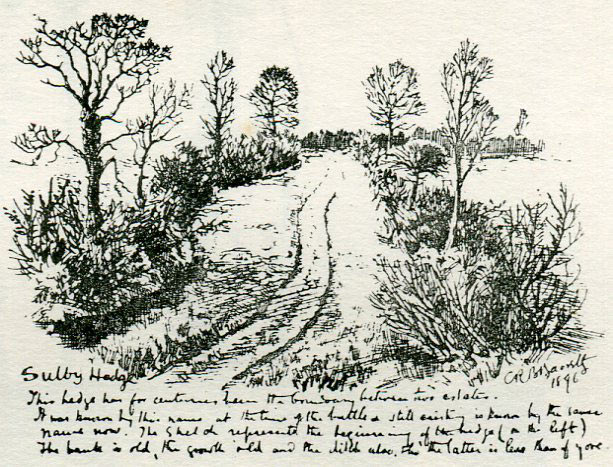

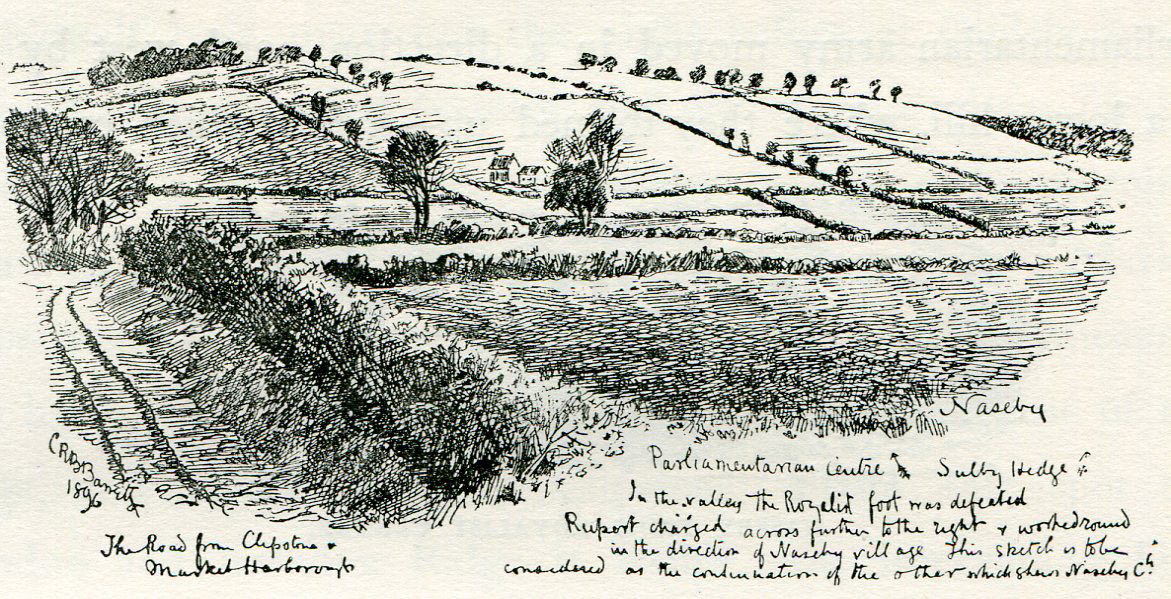

Battlefield of the Battle of Naseby 14th June 1645 during the English Civil War showing the Sulby Hedges: drawing by C.R.B. Barrett

Once the opposing armies were formed up for battle the frontage was about a mile across. A feature of the western side of the battlefield was the Sulby Hedges, a long double hedge marking the boundary between the Sulby and Naseby manor estates.

A major loss to the Royalist army was the absence of Lord Goring’s cavalry. Goring’s men would have gone a long way to redress the imbalance in cavalry numbers between the two sides.

In addition, the movement of the Royalist army over the previous weeks prevented the majority of the artillery from keeping up. In the event artillery played little part in the battle.

The final Parliamentary deployment was to place Colonel Okey’s Dragoons along the Sulby Hedges to fire into the flank of the inevitable Royalist cavalry attack on the western wing.

Soon after Okey’s Dragoons were in place the Royalist line began to advance. The Parliamentary line moved forward over the ridge to confront the attack.

The battle began at 10am. The Parliamentary guns fired a single round as did the musketeers before the two lines met in close battle.

Cavalry attack: Battle of Naseby 14th June 1645 during the English Civil War: picture by Palamedes Palamedesz

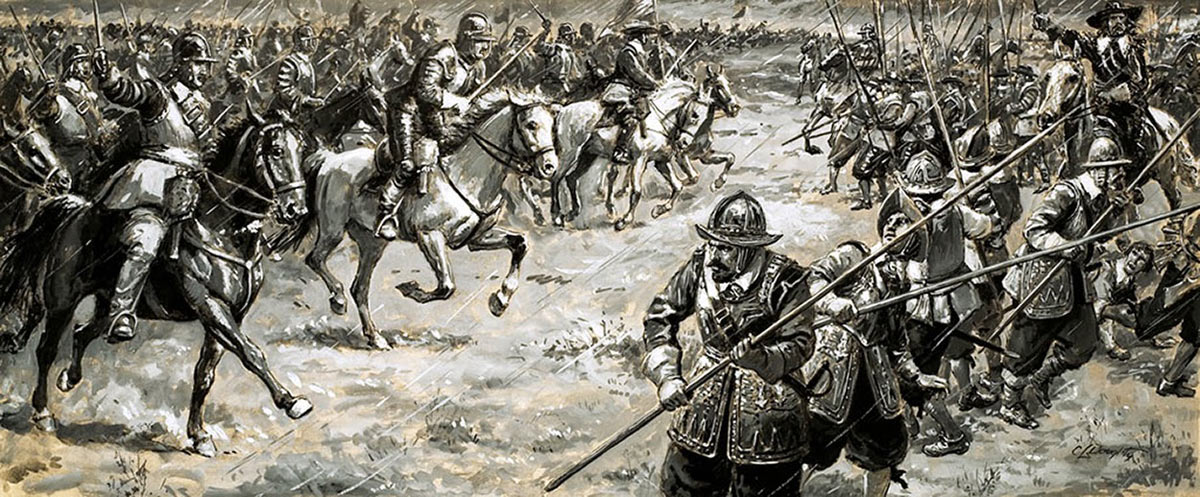

Prince Rupert led his Horse on the Royalist right wing across the valley and charged up the far slope at the Parliamentary Horse of Ireton and Butler. The Earl of Northampton commanded the Royalist second line of Horse.

The Parliamentary Horse on the left wing were routed by Prince Rupert’s regiments, making the perennial mistake of receiving the Royalist charge with pistol fire at the halt (as at the Battle of Edgehill and the Battle of Roundway Down). The Parliamentary Horse of the left wing was driven back.

As at the Battle of Edgehill Rupert’s victorious horsemen chased the Parliamentary troopers off the field and made for the Parliamentary camp near Naseby. Here the camp guard put up a vigorous resistance engaging the Royalist Horse for some time before they could be rallied and brought back.

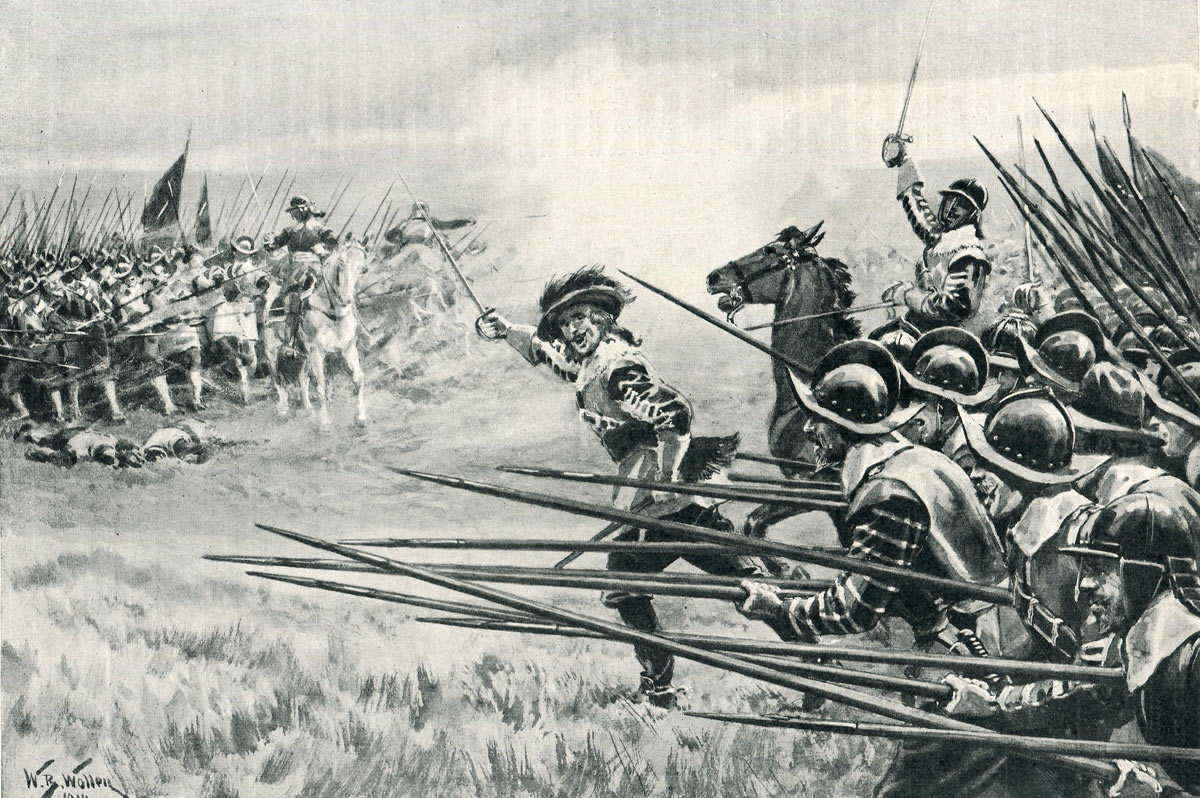

Charge of the Royalist Foot at the Battle of Naseby 14th June 1645 during the English Civil War: picture by William Barnes Wollen

On the main battlefield, at the same time that Prince Rupert struck the Parliamentary Horse of the left wing the outnumbered Royalist Foot reached the Parliamentary line and attacked ferociously.

Major-General Philip Skippon, commanding the Parliamentary Foot was early in the battle struck in the stomach by a musket ball penetrating both his breast plate and thick doublet. Skippon remained in the saddle but the news of his wounding undermined the morale of his soldiers.

The first line of Parliamentary Foot fell back on the second pursued by the Royalist Foot. Colonel Ireton led part of his regiment of Horse that had not been dispersed by Prince Rupert’s charge into an attack on the Royalist Foot, but was driven off by Astley’s men before they attacked the second line of Parliamentary Foot

It was on the Parliamentary right wing that the tide was decisively turned by Cromwell’s Horse. Here Sir Marmaduke Langdale’s Northern Horse advanced up the slope towards Naseby. Cromwell’s regiments attacked down the hill at the gallop sweeping Langdale’s Horse back down the hill.

Cromwell’s Horse attack the Royalist Foot at the Battle of Naseby 14th June 1645 during the English Civil War

It was at this point that Cromwell showed the results of the intense training of his ‘Ironsides’. Cromwell was able to halt his charging troopers and wheel them into an attack on the flank of Astley’s Royalist Foot, while dispatching two regiments, his own and Whally’s to maintain the attack on the broken remnants of Langdale’s Northern Horse.

King Charles I leading his Life Guard forward to the attack: Battle of Naseby 14th June 1645 during the English Civil War

King Charles I at the head of his Life Guard was about to charge the pursuing Parliamentary Horse when his bridle was seized by the Earl of Carnwarth, who is reported to have cried out ‘Will you go to your death in an instant?’ Carnwarth led the King to the rear followed by the Life Guard, which might otherwise have effectively intervened to rescue Langdale’s hard pressed troopers.

Cromwell’s main body of Horse cut into Astley’s Royalist Foot while Colonel Okey brought up his Dragoons, now mounted, from the Sulby Hedges and charged into the Royalist Foot’s other flank. These blows, one on each flank was too much for the Royalist Foot which collapsed into flight and surrender.

One body of Royalist Foot resisted to the end, probably Prince Rupert’s Bluecoats in the reserve, until they were attacked in the front and rear by Parliamentary Horse and annihilated.

Lord Carnwarth taking the King’s bridle at the end of the Battle of Naseby 14th June 1645 during the English Civil War

Seeing the collapse of the Royalist Foot Prince Rupert’s Royalist Horse on the right wing could not be induced to make a further charge and rode off.

Sir Robert Fairfax prevented the Parliamentary Horse from renewing the attack until the Foot were reformed and able to support them. Only then did Fairfax order a general advance finally overwhelming the Royalist Foot and driving the remnants of the Royalist Horse from the field.

On the battlefield of Naseby the main force of Royalist Foot was effectively destroyed.

Casualties at the Battle of Naseby:

As in most of the battles of English Civil War casualties are hard to assess. Probably around 1,000 Royalists were killed with around 4,500 mainly foot soldiers captured.

Among the Royalist prisoners were 8 colonels, 8 lieutenant-colonels, 18 majors, 70 captains and other officers amounting to 500.

The Parliamentary army probably lost around 1,000 killed.

Follow-up to the Battle of Naseby:

The Royalists were given no opportunity to rally, pursued by the Parliamentary Horse ordered on pain of death not to dismount to loot.

Gold Medal of Sir Thomas Fairfax issued by Parliament: Battle of Naseby 14th June 1645 during the English Civil War

All the Royalist guns were taken with most of the baggage. King Charles I’s coach was captured with his correspondence, revealing damaging letters on his attempts to raise Catholic and Continental support for his cause.

This correspondence was speedily published by the Parliament in a volume entitled ‘The King’s Cabinet Opened’.

A great deal of loot from the sack of Leicester was retrieved.

When the Royalist camp was overrun a large number of Welsh women were found. Of these around 100 women were killed by the outraged Parliamentary troops who took them for whores. The remainder of the women were mutilated in the face with their noses slit or other injuries.

King Charles I met Princes Rupert and Maurice at Leicester and rode on to Hereford where he vainly attempted to raise new forces but in effect the war was lost on the field of Naseby.

Oliver Cromwell cheered by his soldiers after the Battle of Naseby 14th June 1645 during the English Civil War: picture by William Barnes Wollen

Lord Carnwarth taking the King’s bridle at the end of the Battle of Naseby 14th June 1645 during the English Civil War

Anecdotes and traditions from the Battle of Naseby:

- Cromwell wrote to Parliament announcing the victory although etiquette dictated that this distinction should have been left to the army commander Sir Thomas Fairfax. Parliament indulged in a series of celebratory dinners assessing that the Battle of Naseby marked the final demise of the King’s fortunes in the war. The main dinner was given by City of London in the Grocer’s Hall when the 46th Psalm was sung ‘hilariously’:…… ‘God is our refuge and strength, a very present help in trouble. Therefore will not we fear, though the earth be removed, and though the mountains be carried into the midst of the sea..’

- The Sulby Hedges were an important feature of the Naseby battlefield marking the edge of the field and providing cover for Colonel Okey’s Parliamentary Dragoons. England was full of such fields widely used by the musketeers and dragoons of each side in the English Civil War for concealment and protection from the opposing side’s Horse. Hedges marked the boundaries between estates or parishes the primary purpose being to confine stock animals. The Sulby Hedges are in the plural because there were two hedges running parallel one belonging to each estate with a path or track between the two (see the drawing by C.R.B. Barrett above). When properly maintained the hedges were shoulder height and a skilled horseman could jump each in turn particularly when hunting. A similar pair of hedges called the ‘Great Hedge’ featured prominently in the Battle of Chalgrove.

- An important Parliamentary casualty was Major-General Philip Skippon shot early in the attack by the Royalist Foot. So important was Skippon to the Parliamentary side for his experience and skill in raising and training the Foot that physicians were sent from London to treat for him. Skippon recovered but it took some months. Skippon was yet another soldier whose career had been forged on the Continent in the Thirty Years War before the outbreak of the English Civil War. Before the war Skippon held an appointment with the Honourable Artillery Company and was made commander of the London Trained Bands.

- Oliver Cromwell’s son-in-law Commissary-General Henry Ireton was wounded in the battle as were the Parliamentary Officers Colonels Cook, Butler and Francis.

- Among the Royalist wounded were the Earl of Lindsay whose father was killed at the Battle of Edgehill, Lord Astley and Colonel John Russell, brother of the Earl of Bedford.

- 12 Royalist cannon, 100 pairs of colours, 8,000 stands of arms, 40 barrels of powder, 200 horses and 200 carriages were captured. The Parliamentary troops took quantities of food, particularly welcome as they were on short rations after the hurried march north.

- The Royalist prisoners were marched to London, held on the artillery ground at Tothill Fields and paraded through the streets of the City.

- Parliament struck an oval medal to commemorate the victory at the Battle of Naseby.

Cromwell after the Battle of Naseby 14th June 1645 during the English Civil War: picture by Landseer

References for the Battle of Naseby:

The English Civil War by Peter Young and Richard Holmes

History of the Great Rebellion by Clarendon

Cromwell’s Army by CH Firth

British Battles by Grant Volume I

The previous battle in the English Civil War is the Second Battle of Newbury

The next battle in the English Civil War is the Siege of Basing House

To the English Civil War index