The battle, fought on 18th June 1643, that hamstrung the Earl of Essex’s army

Prince Rupert Royalist Commander at the Battle of Chalgrove 18th June 1643 in the English Civil War: picture by Ernest Crofts

The previous battle in the English Civil War is the Battle of Wakefield

The next battle in the English Civil War is the Battle of Adwalton Moor

To the English Civil War index

Battle: Chalgrove

War: English Civil War

Date of the Battle of Chalgrove: 18th June 1643

Place of the Battle of Chalgrove: 10 miles to the south-east of Oxford.

Combatants at the Battle of Chalgrove:

The forces of King Charles I against the forces of Parliament.

Colonel John Hampden, second in command of the Earl of Essex’s Parliamentary army, mortally wounded at the Battle of Chalgrove 18th June 1643 in the English Civil War

Generals at the Battle of Chalgrove:

Prince Rupert led the Royalist raiding force into Oxfordshire, fighting the Battle of Chalgrove on his return.

The Earl of Essex commanded the Parliamentary Army in Oxfordshire in June 1643.

Sir Philip Stapleton was in command in the town of Thame on the night of Prince Rupert’s raid and dispatched the Parliamentary troops in pursuit of the Royalists. Stapleton arrived in the field after the battle.

The senior Parliamentary officer in the field during the battle was Colonel John Hampden who was fatally wounded.

Size of the armies at the Battle of Chalgrove:

The Royalist force commanded by Prince Rupert on his raid into Oxfordshire comprised 1,000 Horse, 500 Dragoons and 500 Foot.

Prince Rupert encountered Parliamentary troops at Tetsworth, Postcombe and at Chinnor.

The Royalist force was followed by Parliamentary Horse and Dragoons after it left Chinnor commanded by Major Gunter comprising around 300 men.

Sir Philip Stapleton dispatched 750 Horse from Thame towards Chalgrove to intercept the Royalist force before it could re-cross the bridge over the Thame River (not the River Thames) into Royalist held country.

These 750 Horse encountered the night watch of 300 Horse and immediately before the Battle of Chalgrove joined Major Gunter’s contingent of 300 Horse and Dragoons so that the Parliamentary force that attempted to stop Prince Rupert’s men was around 1,400 Horse and Dragoons.

Prince Rupert Royalist Commander at the Battle of Chalgrove 18th June 1643 in the English Civil War: picture by Anthony van Dyck

Winner of the Battle of Chalgrove: Chalgrove was a convincing Royalist success.

Uniforms, arms and equipment at the Battle of Chalgrove:

See this section in the Battle of Edgehill.

Background to the Battle of Chalgrove:

The origins of the English Civil War are dealt with under this section in the Battle of Edgehill.

With the opening of the 1643 campaigning season the Earl of Essex took the field with an army significantly larger than the Royalist army based at Oxford.

Essex moved on Reading and captured the town in April 1643. The fear on the Royalist side was that Essex would march on Oxford and attempt to take the city.

Essex moved into Oxfordshire but only as far as Thame. Essex’s motive for this advance was to block a Royalist march on London.

Following a report from his scoutmaster-general that the place was badly defended, on 17th June 1643 Essex dispatched a force to take Islip a crossing point over the River Cherwell to the north-east of Oxford as a preliminary for a possible attack on Oxford itself.

Funeral of John Hampden from his statue in Aylesbury: Hampden was mortally wounded at the Battle of Chalgrove 18th June 1643 in the English Civil War

A force of 3,000 Royalist Horse at Bletchingdon quickly took up positions on the ridge overlooking the Cherwell at Islip causing the Parliamentary force to abandon the venture and return to its quarters, some of the troops marching back to Chinnor, the town where they were billeted, involving these men in a march there and back of 40 miles.

In early June 1643 a Scottish Officer Colonel John Urry deserted from the Earl of Essex’s army and made his way to Oxford to offer his services to King Charles I.

Urry conferred with Prince Rupert disclosing to him details of the disposition of the Earl of Essex’s Parliamentary Army. Urry also disclosed that a convoy was daily expected at Thame from London carrying £21,000 in pay for Essex’s army.

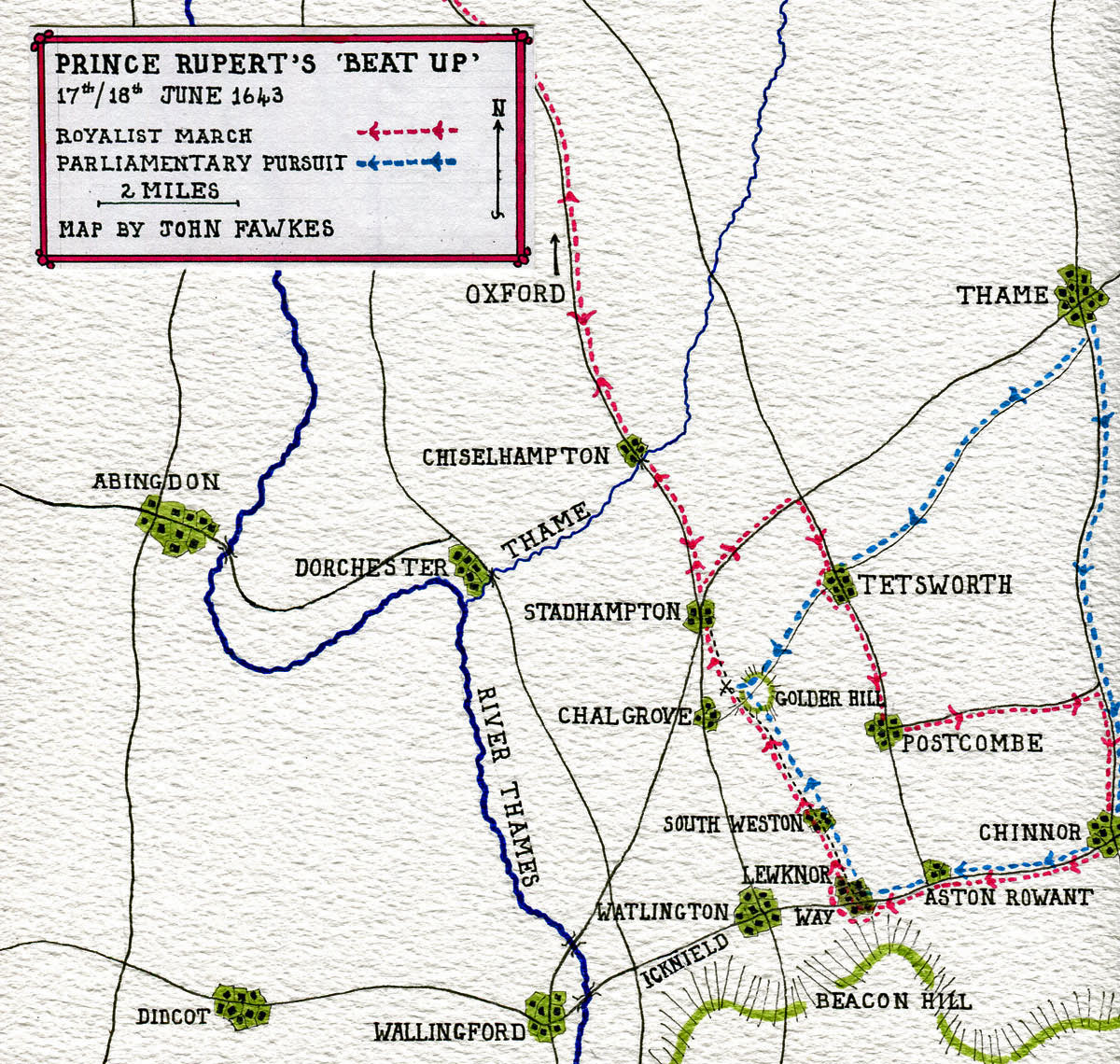

Prince Rupert decided to mount a raid into Parliamentary territory on the south-east side of the Thame River. His force would cross the Royalist held bridge at Chiselhampton and march to Chinnor on the convoy’s expected route, the London to Thame road.

The raid was to be a ‘beat-up’ to capture the convoy and attack as many Parliamentary formations as possible in reprisal for the raid on Islip.

Map of Prince Rupert’s march on 17th and 18th June 1643: Battle of Chalgrove 18th June 1643 in the English Civil War: map by John Fawkes

Account of the Battle of Chalgrove:

Prince Rupert’s force marched out of Oxford across Magdalen Bridge during the afternoon of 17th June 1643, the day of the Parliamentary incursion to Islip.

Prince Rupert’s force comprised three regiments of Horse (Prince Rupert’s Regiment, the Prince of Wales’ Regiment and Lord Henry Percy’s Regiment), the two troops of his own mounted Life Guard, Lord Wentworth’s Regiment of 500 Dragoons and 500 Foot commanded by Colonel Lunsford; 2,000 men in all.

Military train: Battle of Chalgrove 18th June 1643 in the English Civil War: picture by Richard Beavis

The Royalists crossed the Chiselhampton Bridge at around 9pm marched into Stadhampton and turning north marched to the main London to Oxford Road where they turned onto the road and marched south-east.

Passing through Tetsworth at 1am the Royalists came under musket fire from the church grounds.

At Postcombe Prince Rupert’s force encountered men from Colonel Morley’s Regiment of Parliamentary Horse quartered in the village, capturing 9 of Colonel Morley’s troopers, horses and weapons and Colonel Morley’s standard.

Prince Rupert’s men moved on to the small town of Chinnor which they surrounded by 5am. Major Legge led the attack into Chinnor with the advanced guard.

The Parliamentary troops in Chinnor back the previous day from the 40-mile march to Islip and back and exhausted were asleep with inadequate guards posted.

In the ensuing fight the Parliamentary troops were overwhelmed losing 50 dead and 150 prisoners from Sir Samuel Luke’s Regiment of Foot. 3 colours from Luke’s Regiment, many weapons and a quantity of other booty were taken by the Royalist troops.

There was no sign of the Parliamentary convoy carrying the £21,000 in pay. Some reports have it that the convoy was warned and hid in woods. It would seem however that the convoy had already passed along the road and was at Thame by the time Prince Rupert’s force was in Chinnor.

The timings of Prince Rupert’s march do not allow for any significant search of the area. It seems likely that the capture of the Parliamentary troops in Chinnor revealed that the pay convoy had passed through the town the day before.

At 6am the Royalist Foot left Chinnor heading south-west along the Icknield Way in the direction of Watlington. They were weighed down by the booty taken in Chinnor and delayed by the number of prisoners to be escorted.

Prince Rupert led the mounted regiments along the same road out of Chinnor half an hour later at 6.30am.

The Royalist column on the march will have stretched for some two miles.

At 7.30am the Royalist Horse reached the village of Aston Rowant only 2 miles from Chinnor where they encountered 3 troops of Parliamentary Horse, the troops of Major John Gunter, Captain James Sheffield and Captain Richard Crosse.

A Parliamentary picket was seen on Beacon Hill to the Royalist column’s left.

In Thame Sir Philip Stapleton the senior Parliamentary commander who ‘had the watch’ heard the firing at Chinnor and sent two troops of Dragoons to investigate.

A party quickly returned to inform Sir Philip Stapleton that the garrison at Chinnor had been wiped out by a large force of Royalists who were making off towards Watlington along the Icknield Way.

The rest of the Parliamentary Dragoons sent to Chinnor set off in pursuit of Prince Rupert, catching them up at Aston Rowant where Major Gunter’s Horse were endeavouring to interfere with the Royalist withdrawal.

On the march: Battle of Chalgrove 18th June 1643 in the English Civil War: picture by Richard Beavis

At the Parliamentary headquarters in Thame it was clear to Sir Philip Stapleton that the Royalists were intending to reach Oxford via the Chiselhampton Bridge over the Thame River (not to be confused with the main River Thames of which the Thame is a tributary) turning off the Icknield Way around Lewknor and marching through South Weston.

Stapleton dispatched Captain Dundasse’s troop of dragoons towards Chalgrove to intercept the Royalists while he assembled a larger force to follow.

It is an important and remarkable feature of the Battle of Chalgrove that the Parliamentary force sent from Thame later that morning comprised the troop and company commanders of the Earl of Essex’s army who had assembled in Thame to collect the pay for their troops and companies.

The Parliamentary Army was widely distributed in quarters over the east of Oxfordshire. With the dispatch of the two troops of Dragoons to Chinnor and Captain Dundasse’s troop of Dragoons to Chalgrove the only body of mounted soldiers immediately available to Sir Philip Stapleton was the assemblage of troop and company captains.

Sir Philip Stapleton ordered these officers to form a mounted body comprising some 750 men and march as quickly as possible to intercept the Royalist force. The body of officers marched out of Thame at around 8am. Many of these officers were from the Foot and they had not before fought as a single unit.

In the meantime the Royalist force heavily encumbered with Parliamentary prisoners and captured weapons and booty from the Parliamentary regiment routed in Chinnor was passing through South Weston, harassed in the rear by the 300 Horse and Dragoons led by Major Gunter.

Prince Rupert’s Life Guard commanded by Lieutenant-Colonel Daniel O’Neale and Lord Percy’s Regiment of Horse attacked Gunter’s men and drove them off in disorder.

Medieval brass in Chinnor Church with bullet holes: Battle of Chalgrove 18th June 1643 in the English Civil War

Soon after this engagement Captain Dundasse’s Dragoons came up with Major Gunter and Gunter dispatched Dundasse to Thame to inform Sir Philip Stapleton of the developments. Dundasse reached Thame at around 9.30am.

Also at around 9.30am Major Gunter’s force of Horse and Dragoons was joined by the body of troop and company captains from Thame and Gunter took overall command of the force.

Also in the area was Colonel John Hampden, second-in-command to the Earl of Essex accompanied by Colonel John Dalbier, the Parliamentary quartermaster-general and Sir Samuel Luke, whose regiment had been annihilated in Chinnor. Hampden, who had no cavalry experience joined Captain Crosse’s troop (one of the troops from Aston Rowant) in Gunter’s ad hoc force now numbering around 1,000 mounted men, many of them infantry officers, for the attack on Prince Rupert’s retreating force.

Gunter faced three Royalist Regiments of Horse of proven aggression and skill on the battlefield commanded by Prince Rupert, a ruthlessly effective commander of cavalry. The two forces of cavalry were roughly equal in size.

The Royalist column strung out with prisoners and looted weapons and valuables stretched over 2 miles of the track, the Foot with the prisoners and wagons to the front, followed by the Dragoons and then the body of Horse.

The route to the Chiselhampton bridge took the Royalist column along a track bounded by a ‘Great Hedge’ that acted as a parish boundary. The ‘Great Hedge’ was a double hedge running east to west with a narrow track between the two sections of hedge and was of sufficient height to be strock-proof, probably shoulder height.

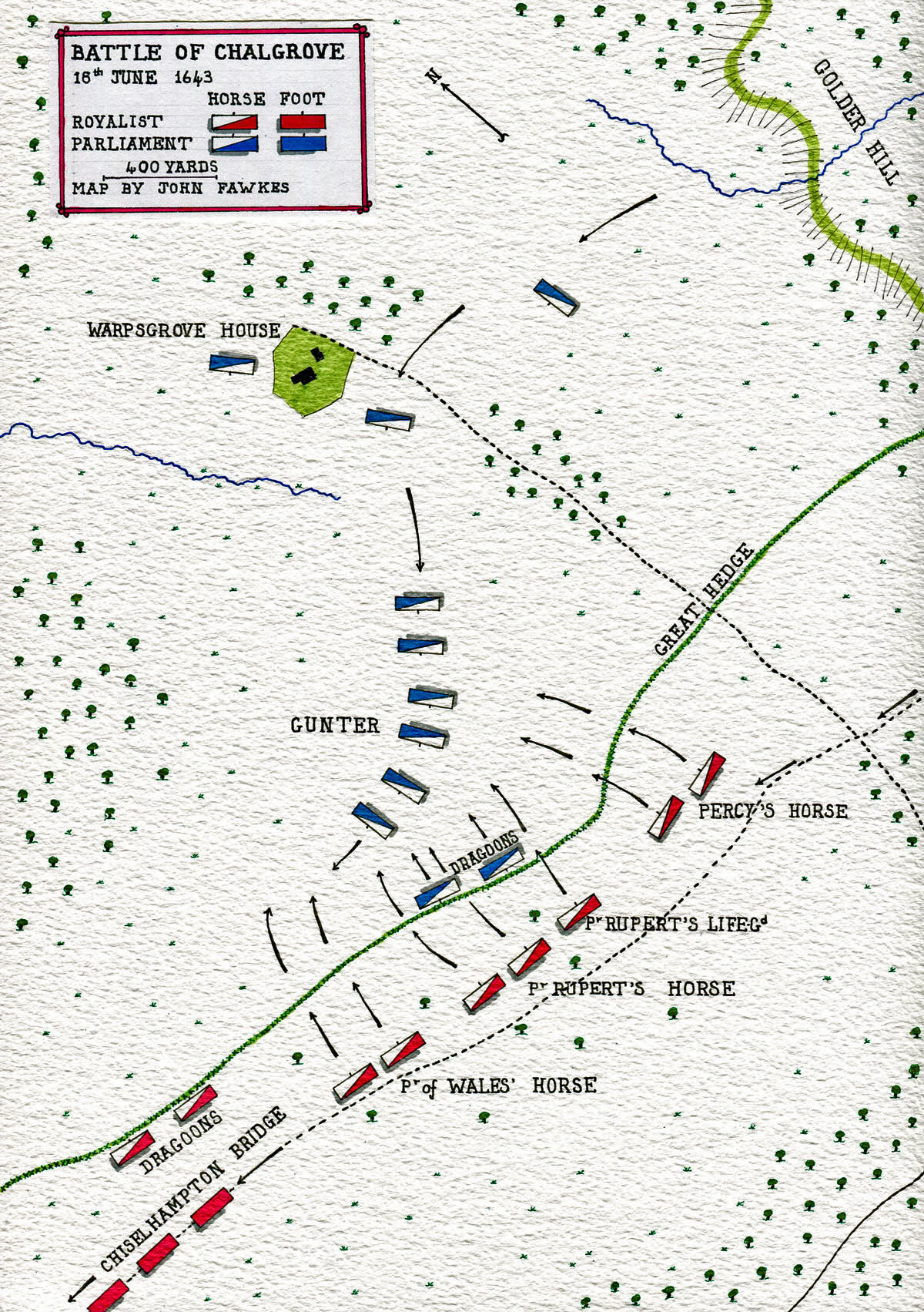

On reaching the area of Chalgrove Prince Rupert wheeled his regiments of Royalist Horse into line in a field facing the Parliamentary cavalry that were appearing over Golder Hill to the south-east while the Royalist Foot continued along the track to the Chiselhampton bridge with the prisoners, captured weapons and other loot. The Dragoons acting as a rearguard to the Foot dismounted and lined the hedgerows in ambush against any Parliamentary pursuit.

The Royalist Horse formed with Prince Rupert’s Regiment in the centre with the Prince’s Life Guard to its right, the Prince of Wales’ Regiment on the left flank and Lord Percy’s Regiment on the right flank.

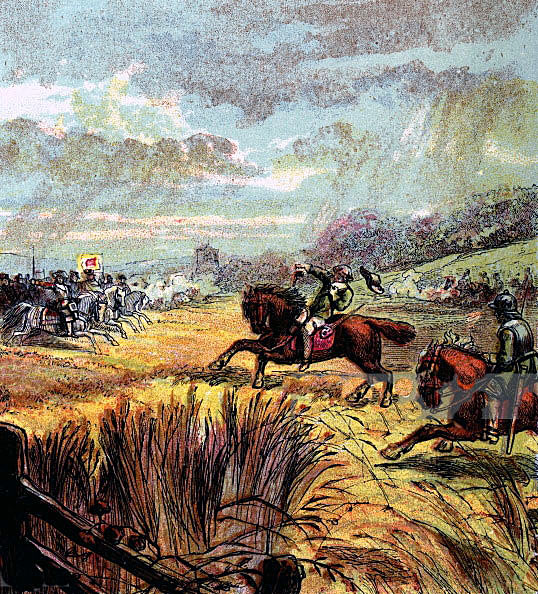

Cavalry action at the time of the English Civil War: Battle of Chalgrove 18th June 1643 in the English Civil War: picture by Pieter Meulener

The Parliamentary Horse approached down the slope of Golder Hill from the direction of Thame entering a long field separated from the Royalist Horse by the Great Hedge. The Parliamentary Horse held back at the top end of this long field.

Prince Rupert ordered his troopers to continue the retreat after the Royalist Foot to entice the Parliamentary force to approach nearer. It would seem that at this stage Prince Rupert had in mind to lure the Parliamentary Horse into the ambush set further along the track by the Royalist Dragoons.

The Parliamentary Horse and Dragoons moved down the field towards the Great Hedge, the Horse turning to follow the direction of the Royalist column moving parallel to it along the Great Hedge, while the Parliamentary Dragoons dismounted took positions behind the Great Hedge and opened fire on the Royalist Horse, inflicting some casualties.

This main body of Parliamentary Horse is described in ‘the late beat up’ as comprising 8 troops or cornets of men. ‘The late beat up’ describes a reserve of three troops of Parliamentary Horse at the top of the field near to Warpsgrove House while a further small reserve was at the base of Golder Hill.

The advice of his senior officers to Prince Rupert was to continue after the Foot and permit the Parliamentary Horse to encounter the ambush set by the Royalist Dragoons further along the track. Prince Rupert took the view that the Parliamentary force was too close for such a course. He was resolved to attack, as was always his inclination.

The fire of the Parliamentary Dragoons caused Prince Rupert to retort ‘Yeah their insolency is not to be endured’ and wheeling his horse he leapt the Great Hedge. Prince Rupert was immediately followed by 15 men of his Life Guard that he formed into a line. The rest of the Life Guard got through or over the Great Hedge, described in the Royalist account as ‘jumbled over after him’.

The Parliamentary Dragoons remounted and hurried away back up the hill.

Field near Chalgrove seen over the Great Hedge: Battle of Chalgrove 18th June 1643 in the English Civil War

Lieutenant-Colonel Daniel O’Neale led Prince Rupert’s Regiment around the Great Hedge to the left of Prince Rupert’s Life Guard putting his regiment immediately in front of the Parliamentary Horse. The Parliamentary Horse fired two pistol and carbine volleys before Prince Rupert’s Regiment led by O’Neale charged home on them.

Prince Rupert charged the left flank of this body of Parliamentary Horse with his Life Guard and was followed into the attack by Lord Percy’s regiment which had found a way through or around the Great Hedge.

At the other end of the Royalist Horse line the Prince of Wales’ Regiment led by Major Daniel attacked the right flank of the Parliamentary Horse.

The Parliamentary Horse would seem to have been largely still in column and received the Royalist charge at the halt with small arms fire, always a fatal response to a mounted charge.

The Royalist account describes the Parliamentary Horse as putting up an unusually stiff resistance with pistol fire. This is consistent with the troops being largely officers.

Inevitably the Parliamentary Horse were driven back on the 3 troops positioned near Warpsgrove House which were in turn routed.

Prince Rupert’s three regiments pursued the defeated Parliamentary Horse for a mile and a quarter back over Golder Hill towards Thame before halting and returning to their original route for the Chiselhampton bridge.

The defeated and fleeing Parliamentary Horse and Dragoons were met further up the Thame Road by Sir Philip Stapleton coming up with his regiment. Stapleton stopped the rout but did not pursue the Royalist force.

Both in the initial charge and in the subsequent melee with pistols and swords the Parliamentary Horse and Dragoons were severely handled and suffered substantial casualties one of whom was Colonel John Hampden fighting as a trooper. Major Gunter was killed in the fight by the Great Hedge.

The Royalist force reached Oxford at 2pm and was greeted with an ecstatic welcome as it entered the city with its haul of prisoners and booty and accounts of the successful cavalry action.

Cavalry battle: Battle of Chalgrove 18th June 1643 in the English Civil War: picture by Palamades Palamadesz

Casualties at the Battle of Chalgrove:

It seems that the Parliamentary side suffered 100 men killed in the battle (at Chinnor and Chalgrove) and lost 200 prisoners to the Royalists (120 taken at Chinnor and 80 at Chalgrove).

The significant feature of the loss for Parliament was that the casualties at Chalgrove comprised a number of the troop and company commanders from across Essex’s Parliamentary army assembled in Thame to collect their soldiers’ pay and sent in the emergency to intercept the Royalist raiders.

A Parliamentary source complained that 13 captains and 18 other men of note were murdered in Oxford Prison after the battle. It seems more likely that they died in the battle.

Old Nags Head in Thame used by the Parliamentary army as a quarter: Battle of Chalgrove 18th June 1643 in the English Civil War

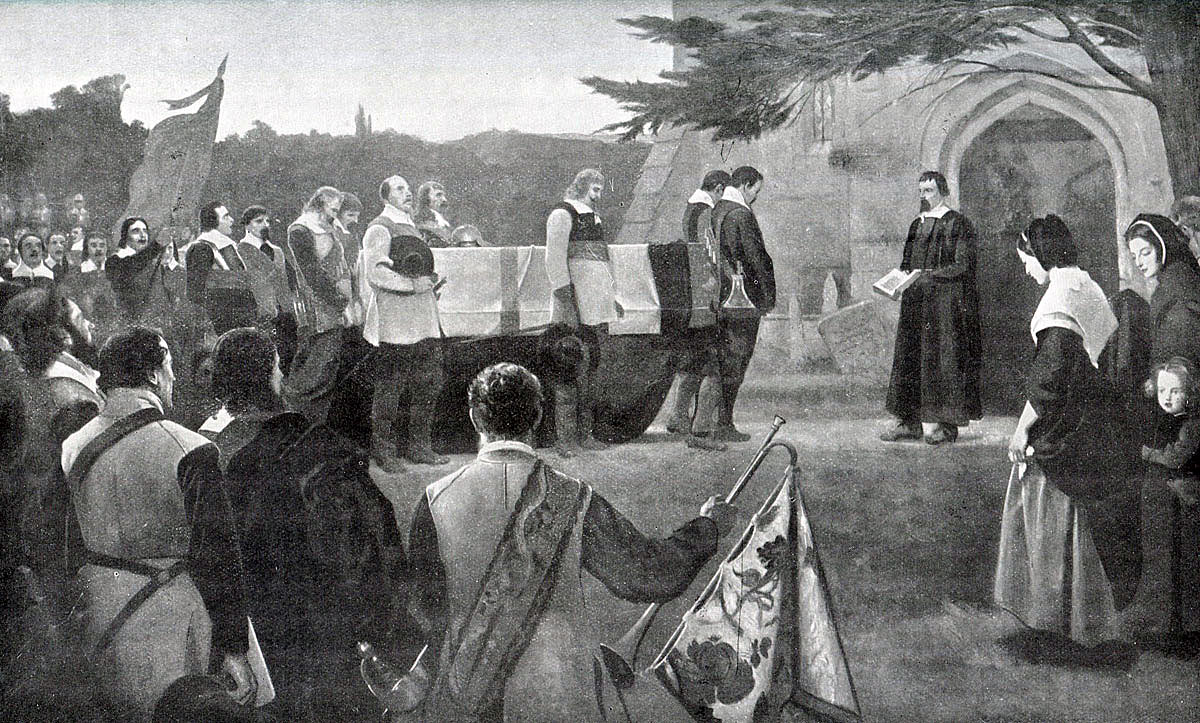

A substantial loss to the Parliamentary side was the death of John Hampden. Hampden received two bullets in the shoulder during the melee by the Great Hedge. He was taken to the Greyhound Inn in Thame where he died on 24th June 1643.

Royalist losses were insignificant and are not reported.

Follow-up to the Battle of Chalgrove:

The Earl of Essex’s Parliamentary Army is considered to have collapsed after the Battle of Chalgrove.

This is far from surprising. The important sub-unit in a regiment was the troop or company. The officers commanding these sub-units were the officers known to the soldiers and to whom the soldiers felt loyalty. The troop or company commander was responsible for paying the men in his sub-unit, hence their presence in Thame when Sir Philip Stapleton took the unfortunate decision to dispatch these officers ‘en masse’ to intercept Prince Rupert. As the colonel, lieutenant-colonel and major in a regiment also commanded a company it may be that a number of field officers fought as troopers in the battle and were among the Parliamentary casuatlies.

At a stroke Essex’s army lost a significant number of middle ranking officers who could only be replaced by more junior and less experienced men.

The sudden loss of so many troop and company commanders in an already dispirited army would have led to a further deterioration in morale and discipline and increased desertion.

A week after the Battle of Chalgrove Colonel John Urry led a Royalist raiding party in an attack on West Wycombe where they surprised a force of Parliamentary Recruit Dragoons, killing many of them.

Before the Battle of Chalgrove Queen Henrietta Maria was in Bridlington with a convoy of armaments unable to move for fear of being intercepted by the Earl of Essex. Nine days after the Battle of Chalgrove Essex withdrew his army to the area of St Albans in Hertfordshire enabling the Queen to bring her convoy to Oxford, escorted by Prince Rupert.

Funeral of John Hampden, mortally wounded at the Battle of Chalgrove 18th June 1643 in the English Civil War

Anecdotes and traditions from the Battle of Chalgrove:

- The main Royalist account of the Battle of Chalgrove appeared in a pamphlet entitled “His highnesse prince Rupert’s late beating up of the rebels quarters” (referred to as ‘the late beating up’) while the Parliamentary version was contained in a pamphlet entitled ‘A True Relation of a Gret Fight Between the Kings Forces and the Parliaments, At Chinner neer Tame on Saturday last’ and two letters from the Earl of Essex to Parliament which discounted the seriousness of the Parliamentary defeat. The Parliamentary accounts are considered unreliable.

- John Hampden: In his book ‘History of the Great Rebellion’ the Earl of Clarendon speaks at length of the outstanding character and ability of John Hampden even though Clarendon was a Royalist and Hampden supported Parliament. While the Ship Money tax imposed by King Charles I in the 1630s was widely resisted across the country the main case was brought against John Hampden and rumbled on in the Court of the Exchequer until finally the judges ruled against Hampden. The decision was a pyrrhic victory for King Charles I. Hampden was one of the five Members of Parliament that the King attempted to arrest in 1642 leading directly to the outbreak of the English Civil War. Hampden raised his own regiment of Parliamentary Foot. Hampden’s diplomatic skills acted to smooth the friction between the Earl of Essex and Parliament once the Civil War began. Clarendon described the death of Hampden as causing to the Parliamentary faction ‘as great a consternation of all that party as if their whole army had been defeated or cut off.’

- Colonel John Hampden’s Parliamentary Regiment of Foot was in quarters at Watlington and took no part in the Battle of Chalgrove.

- Colonel John Urry: Urry saw service on the Continent before returning and joining the Scottish Covenanter Army. With the outbreak of the English Civil War Urry joined the Earl of Essex’s Parliamentary Army and fought at the Battle of Edgehill and the Battle of Brentford before changing sides. Urry was knighted on the evening after the Battle of Chalgrove. Urry with Sir Charles Lucas commanded the successful Royalist Left Wing at the Battle of Marston Moor. After the battle Urry deserted to the Parliamentary side and was sent to Scotland to fight against the Marquess of Montrose. Urry was defeated by Montrose at the Battle of Auldearn following which he again deserted to the Royalist side. Urry was captured by the Scottish Covenanters and executed in Edinburgh on 29th May 1650.

- The expression ‘beat up’ was used to describe an unexpected raid on the opposing side’s quarters during the English Civil War. Prince Rupert’s Chinnor/Chalgrove Raid was undoubtedly the most successful example in the English Civil War but was closely followed by the Parliamentary Commander Sir William Waller’s raid on Alton on 13th December 1643.

References for the Battle of Chalgrove:

The Military and Political Importance of the Battle of Chalgrove (1643) by Derek and Gill Lester

English Heritage Battlefield Report: Chalgrove 1643

The King’s War by C.V. Wedgwood

The English Civil War by Peter Young and Richard Holmes

History of the Great Rebellion by Clarendon

Cromwell’s Army by CH Firth

British Battles by Grant Volume I

The previous battle in the English Civil War is the Battle of Wakefield

The next battle in the English Civil War is the Battle of Adwalton Moor

To the English Civil War index