The trench fighting outside Sevastopol in 1854 and 1855 during the Crimean War, a foretaste of the terrible warfare of the American Civil War and the First World War

French troops storming the Malakhov on 8th September 1855: Siege of Sevastopol September 1854 to September 1855

The previous battle in the Crimean War is the Battle of Inkerman

The next battle in the British Battles sequence is the Siege of Delhi

Battle: Siege of Sevastopol

War: Crimean War

Date of the Siege of Sevastopol: September 1854 to September 1855

Account of the Siege of Sevastopol:

The central theme running through the Crimean War was the appalling siege of Sevastopol, a foretaste of the trench fighting of the American Civil War, ten years later, and finally the First World War from 1914 to 1918.

Daily, hundreds of cannon battered down fortifications that the Russian troops were forced to re-dig before the next day’s bombardment. French and British soldiers manned the siege trenches through two harsh winters, in the first with almost no winter equipment. Sorties led to hand to hand fighting along the entrenchments. The Russians developed the art of sniping from the ‘rifle pits’ dug in no man’s land. The predominant experts were the engineers and the artillerymen; the flamboyant actions of the cavalry a world away.

Following the successful Battle of the Alma on 20th September 1854, the British and French allies resolved not to make a direct attack on the Russian Naval Base and City of Sevastopol from the north, but to march around the city and besiege it from the south and east.

On the 25th and 26th September 1854, the British and French armies, with a Turkish contingent, completed the march, by the Traktir Bridge over the Tchernaya River and onto the Fedioukine Hills.

While the British and French armies marched around the city, the Russian commander, Prince Menshikoff, took the preponderance of his army out of Sevastopol, across the Tchernaya and off to the north-east. Menshikoff’s aim was to prevent his army being bottled up in the city and to enable him to receive the reinforcements that were on their way from the north of the Crimea and other parts of Russia.

The British and French prepared for the formal siege of Sevastopol. Each army needed a secure base on the Black Sea, through which to bring in their heavy siege guns, ammunition and supplies and equipment needed to maintain the siege lines.

The British selected the fishing harbour of Balaclava, leaving the French to move to the left of the siege lines and establish their base in the small port of Kamiesh, on the south western tip of the Crimea.

The British and French engineers and troops began to build the siege lines along the Chersonese Uplands to the south of the City, digging redoubts, batteries for the guns and lengths of trench.

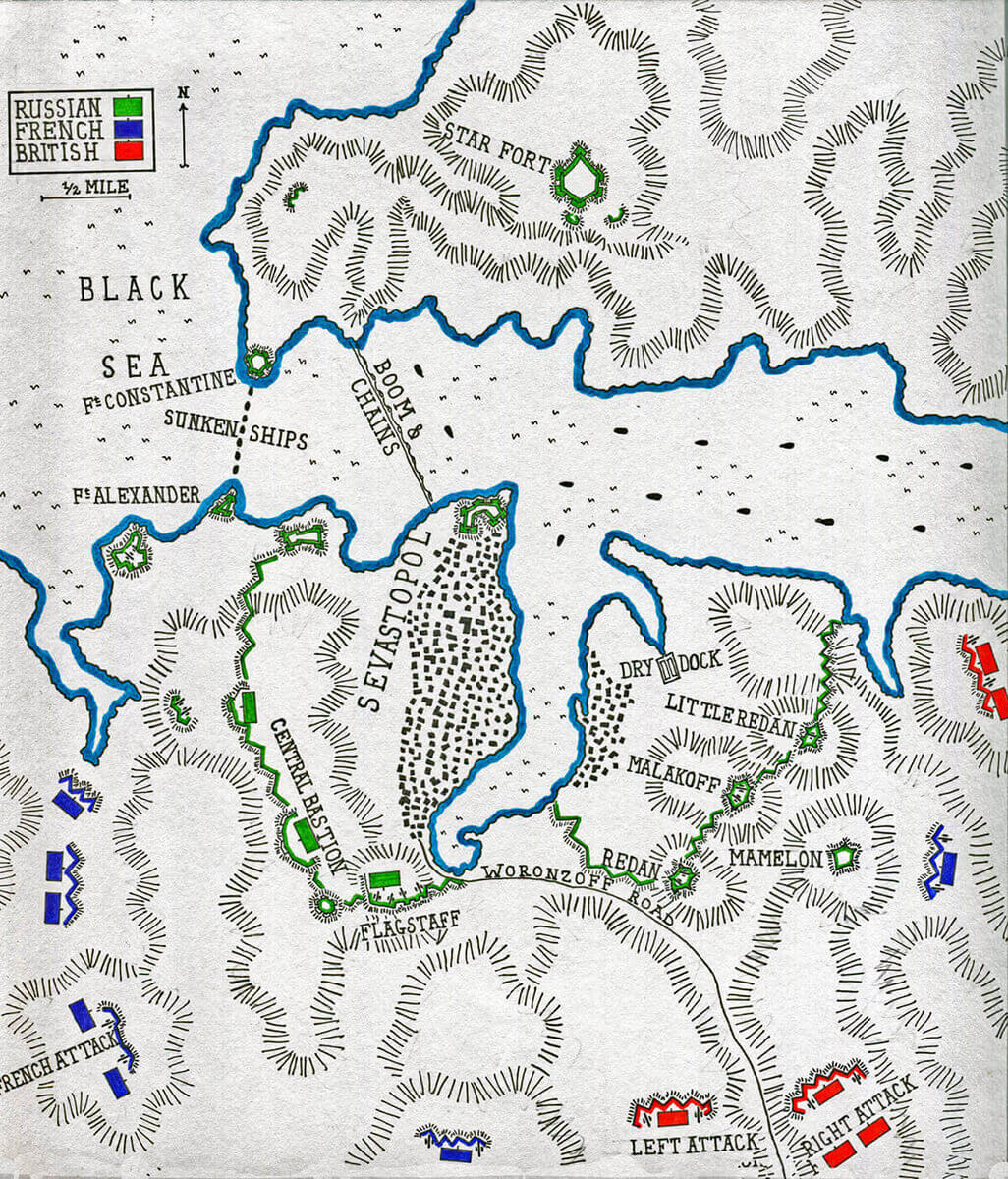

Sevastopol harbour is joined to the Black Sea by a four-mile creek, its mouth guarded by two forts, Constantine on the north side and Alexander on the south. Other forts lay along the creek and further out to sea. The city of Sevastopol lay on the south bank of the creek. To the east and some miles away, the River Tchernaya flowed in a curve around the city. The Chersonese plateau overlooked the city borders and, to the east, the plateau was cut by a number of deep ravines, the site of the Battle of Inkerman.

Around the edge of the city, along its fortifications, stood a number of redoubts that were to be fought over during the siege: the Malakhov, the Redan, Flagstaff Bastion, the Little Redan and others.

A great ravine ran north to south across the Chersonese, marking the divide between the French lines on the left and the British on the right.

Immediately following their defeat on the Alma, the Russians sank a line of warships across the entrance to Sevastopol harbour, to prevent the Allied fleets from entering.

From the beginning of the siege and, particularly after Prince Menshikoff left the city with his field army, the defence of Sevastopol was led and inspired by Admiral Kornilov, until his death, and Lieutenant Colonel Todleben, Menshikoff’s chief engineer.

Menshikoff left in the city: 4,500 militia, 2,700 gunners, 4,400 marines, 18,500 naval seamen and 5,000 workmen: a garrison of 35,100 men.

After the Battle of the Alma, the British and French were seen to march around the city and appear on the Chersonese Uplands, demonstrating to the Russians that the siege would be fought out on the south side of the city.

At this point, earth batteries and stone walls ran from the Great Ravine to the sea. Elsewhere, the proposed defences along the south side of the city were marked out, but little of the work was completed. Todleben set his men to build further defences and armed the new works with heavy guns, many from the ships sunk across the harbour entrance. Other ships were used to cover points accessible to naval gunfire from the harbour and the creek.

British troops storming the Redan: Siege of Sevastopol September 1854 to September 1855: picture by Henri Dupray

On 2nd October 1854, the Russians sent all non-combatants out of the city to the north.

On 9th October 1854, the French ‘broke ground’ (began to dig their trench system) and the British followed suit on the next night. By 16th October 1854, the Allied positions were ready and equipped with 126 guns in batteries. The Russians mounted 118 guns in batteries. A further 200 Russian guns were in place to fire on attacking infantry.

It was intended that the Allied bombardment of the defences would begin on 17th October 1854. The generals wished the French and British fleets simultaneously to attack the forts at the entrance to the harbour, an operation the admirals were reluctant to undertake, the advantage lying very much with the defence.

At 6.30am on 17th October 1854, the Allies began the bombardment of Sevastopol. At 10.30am a Russian shell exploded in the magazine of the French battery on Mount Rudolph, blowing it up and destroying the battery. The remaining French guns were soon silenced. The general infantry assault that was to follow the bombardment was abandoned.

The British fire on the Malakhov Redoubt was equally effective. The magazine was blown up and many of the guns in the redoubt silenced. Admiral Korniloff, who was directing the defence of the Malakhov, was killed. The Russians were thrown into considerable disarray. If the British had continued with the intended assault, it is thought that the Malakhov would have fallen and probably with it the city. But no assault was launched in view of the condition of the French army, after the explosion in the Mount Rudolph battery.

Hot Day in the British Batteries: Siege of Sevastopol September 1854 to September 1855: picture by William Simpson

The British and French Fleets bombarded the Russian forts for some hours, suffering considerable damage and inflicting little in return, before retiring out to sea.

On the 18th October 1854, the British resumed the bombardment without the assistance of the French guns. Dawn revealed that the Russians had almost entirely rebuilt the great sections of parapet thrown down in the previous day’s bombardment. The Allies experienced for the first time the phenomenon that, however much was destroyed in a day’s bombardment, the Russians would usually repair the damage overnight.

During the rest of October and November 1854, the siege continued, while the Battle of Balaclava and the Battle of Inkerman took place beyond the siege works.

Loss of the Prince in the storms on 14th November 1855: Siege of Sevastopol September 1854 to September 1855

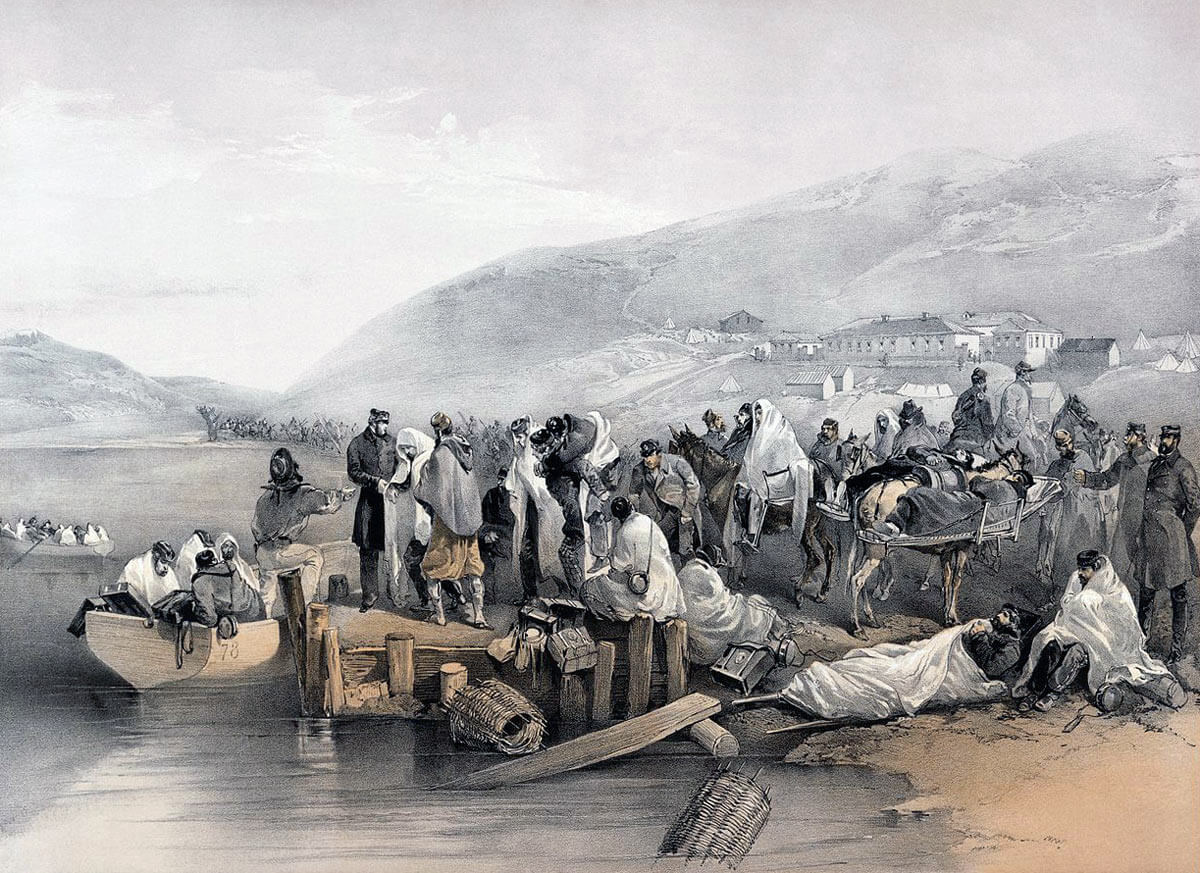

In November 1854, the weather turned from mild autumn to winter. On 14th November 1854, the Great Hurricane struck, destroying much shipping in the British and French bases and tearing away the tents in which the troops had been living. 21 ships were wrecked in Balaclava, containing the stores needed for survival through the winter and to conduct the siege. On the evening of the storm it began to snow.

Russian Cossacks on the move: Siege of Sevastopol September 1854 to September 1855: picture by OFilippov

The siege for the Allies became a nightmare, with the trenches flooded and no proper shelter for the troops when off-duty.

Over the winter, lack of proper supply systems brought the British Army in the Crimea to the brink of starvation. Huge numbers of troops fell sick and the horses and mules died in droves.

During the winter of 1854/1855, Todleben laboured to extend the fortifications around the Redan, the Flagstaff Bastion and the Malakhov. Sir John Burgoyne, the British chief engineer and son of Major General John Burgoyne of the Battle of Saratoga in the American Revolutionary War, was of the view that the capture of the Malakhov was the key to taking Sevastopol. Siege works were opened, to bring the Allied troops near enough to assault the Malakhov.

After the Battle of Inkerman, the Russians gave up the idea that the British and French could be defeated in the field and infiltrated men from the field army back into Sevastopol to reinforce the garrison.

Todleben evolved the idea of digging rifle pits overnight, from which to snipe at the besiegers. The idea was successful and the Russians extended the system all along the line. On 20th November 1854, a party of the Rifles attacked a line of pits and overcame them.

In the same month, the French began a mine under the Flagstaff Bastion. The Russians dug countermines and a system of warfare to be seen sixty years later, on the Western Front in France, established itself with attacks to capture the lips of blown mines.

In November 1854, the activities of the combatants focused on a small hill in front of the Malakhov, called the Mamelon. The fighting to capture this feature raged through the winter of 1854, to March 1855, when the Russians finally took the Mamelon.

On the night of 22nd March 1855, the Russians launched a sortie of some 5,500 men against the French positions covering the Mamelon. The French troops resisted stoutly and finally the Russians were driven back into Sevastopol. Simultaneous with the assault on the French, the Russians attacked the siege works at several points but were driven out in every case.

In February 1855, the Russians attempted to capture Eupatoria, a town some thirty miles to the north of Sevastopol, held by Turkish troops. The attack was repelled, substantially due to naval support.

Also in February 1855, the Russians sank a second line of ships across the entrance to Sevastopol harbour.

With the arrival of spring, the circumstances of the British and French armies improved out of recognition. A city of huts sprang up along the Uplands. The troops were properly clothed and fed. The horses were restored to health. A railway was built from Balaclava to the siege lines, to bring up supplies. A vast concentration of guns was established along the British and French lines, with an abundance of ammunition: 378 French guns and 123 British guns.

On Easter Sunday, 8th April 1855, the British and French began a heavy bombardment of the city’s defences. A weapon that made its first appearance was a mortar, firing an exploding projectile in a high arc from a position out of sight of the enemy.

Over the next 10 days, the British and French silenced the fire of the Russian guns along the defence lines. However, there was no British or French infantry assault. During this period, the Russians lost 6,000 killed and wounded from their gunners and infantry. The British and French lost 1,600 men.

On 21st February 1855, The Tsar Nicholas II died and his son Alexander II took the Russian throne.

On 19th April 1855, Lieutenant Colonel Egerton attacked the rifle pits in front of the Redan, with his 77th Regiment. The 77th drove the Russians out at the point of the bayonet, without firing a shot. The 77th suffered many casualties and later that night Colonel Egerton was himself killed. His men carried him back to camp, meeting his wife on the track.

On 16th May 1855, General Canrobert resigned command of the French Army and was replaced by General Pélissier.

On 22nd May 1855, the British and French sent an expedition to capture and sack the eastern Crimean port of Kertch.

Russian troops inside the Malakhov: Siege of Sevastopol September 1854 to September 1855: picture by Grigory Shukaev

On the night of 21st May 1855, a savage battle took place between the French and the Russians over a length of trench the Russians had built at the western end of the siege works. The next night, the French renewed the attack and captured the trench. Casualties for each side during the two nights of fighting were around 600 men.

British 10th Hussars and French Chasseurs D’Afrque driving back the Russians at the Battle of the Tchernaya: Siege of Sevastopol September 1854 to September 1855: picture by Orando Norie

On 25th May 1855, General Canrobert, now a divisional commander, crossed the Traktir Bridge and drove the Russians back, before returning to the southern side of the Tchernaya River.

British 10th Hussars and French Chasseurs D’Afrque driving back the Russians at the Battle of the Tchernaya: Siege of Sevastopol September 1854 to September 1855: picture by Orando Norie

It was at this time, that a contingent of 15,000 troops arrived from the Kingdom of Sardinia, commanded by General La Marmora, and took up position on the French right.

French, Turkish and Sardinian infantry driving back the Russians at the Battle of the Tchernaya on 16th August1855: Siege of Sevastopol September 1854 to September 1855

At 3 pm on 6th June 1855, a heavy bombardment opened. The French batteries on Mount Inkerman fired on the Malakhov. The British bombarded the Malakhov and the Redan. 540 guns fired from each side.

French troops storming the Mamelon on 7th June 1855: Siege of Sevastopol September 1854 to September 1855

Overnight, the Russians wrought their usual near miraculous restoration of the works. The bombardment resumed on 7th June 1855 and threw down the defensive works again.

At 6.30 pm the French launched their attack. At 5.30 am the next morning, the attack was renewed and the Mamelon captured by three columns of French Zouaves, Turcos and Chasseurs, commanded by General Bosquet.

The French, in their enthusiasm, continued the attack up to the Malakhov, but were driven back to the Mamelon. Further French attacks took place along the line and, by dawn, the Russians had been driven from all their outworks, which the French converted into their front line. French casualties were 5,440 killed, wounded or captured, British 693 and Russian 5,000.

This very successful form of operation; a full day’s bombardment with an hour’s bombardment the next morning, followed by an infantry assault; was to be repeated by the French and the British on 17th/18th June 1855.

General Pélissier, the French Commander-in-Chief then committed two blunders: in a fit of pique, he replaced the experienced and popular General Bosquet, as the commander of the French assault, with a general who had arrived in the Crimea only two days before and knew little of the area. The second blunder was, at the last moment, to dispense with the short morning bombardment, that, in the first attack, knocked down the Russian defences, re-built overnight.

The Russians, alert to the attack, equipped the forward positions with field guns, which mowed down the attacking parties: the morning bombardment would have destroyed these guns.

Only in one section of the line was the attack successful. General Eyre, with a brigade of 2,000 British troops, captured buildings and a cemetery at the bottom of Picket House Ravine. The troops held this position all day under heavy artillery fire. The cemetery was fortified overnight by the Royal Engineers and became part of the allied line. Eyre was wounded in the fighting and 600 of his men became casualties.

Losses in the bombardment and assault were: French 3,500 killed, wounded or captured, English 1,500 and Russian 5,400. Of the six British and French commanders in the attack, four were killed and one severely wounded.

The failure of the 18th June 1855 attack and the heavy casualties are said to have weighed heavily on Lord Raglan, the British commander-in-chief and, on 28th June 1855, after a bout of relatively minor cholera, he died. It is said that the French commander-in-chief, General Pélissier, stood by his deathbed and wept for an hour.

During the bombardment in early June 1855, the Russian garrison in Sevastopol lost 1,000 to 1,500 men a day. The British and French works everywhere encroached upon the defences.

On 9th August 1855, Prince Gorschakoff convened a council of war of the senior Russian officers. It was resolved that the Russian field army attack the French and Sardinian troops on the Fedioukine Hills.

The attack was made by General Liprandi on 15th August 1855. His troops crossed the Tchernaya River and made several assaults upon the French positions, but each time were driven off with heavy loss. Liprandi finally withdrew away to the north-east. The effort to relieve Sevastopol had failed.

The final assaults on the city took place on 8th September 1855.

The French observed that the Russians relieved the garrisons in the major works daily at midday. To avoid the overcrowding and consequent loss from having the old and the new garrisons in the works at the same time, the Russian practice was to march out the old before bringing in the new. Consequently, for a time around midday, the defensive works were denuded of men. The assault was to take place at that time.

Roadways were prepared through the siege works, to enable the attacking troops to mass in the front line. The areas of the defences to be attacked were; the Malakhov, the Curtain, the Little Redan and the Flagstaff Bastion. The Redan was to be assaulted by General Codrington and the British Light Division, with General Markham’s Second Division.

The British and French bombardment began on 5th September 1855 and continued on 6th and 7th. Two Russian naval ships in Sevastopol harbour were set alight by the cannonade.

French troops storming the Malakhov on 8th September 1855 : Siege of Sevastopol September 1854 to September 1855: picture by Adolphe Yvon

As before, the Russians rebuilt the damaged works each night. On the morning of 8th September 1855, the Russians manned the defences with infantry and field guns, expecting the assault to take place, as before, in the early morning after a hurricane bombardment.

But it was not until midday that the assault began and the surprise of the Russians worked out as the French commander-in-chief calculated. There was little fire on the attacking columns of General Bosquet, as they stormed the Russian positions.

French troops storming the Malakhov on 8th September 1855 : Siege of Sevastopol September 1854 to September 1855: picture by Horace Vernet

The French poured into the Malakhov and took the advanced works. The Russians emerged from the interior of the bastion and counter attacked. The fighting in the Malakhov raged until 4pm, when finally the French took the bastion. Equally savage fighting raged over the Little Redan and the Curtain, before they were taken.

British attack on the Great Redan on 8th September 1855: Siege of Sevastopol September 1854 to September 1855 in the Crimean War

The British had less success against the Redan. The rocky nature of the ground prevented the digging of works to protect the attacking columns and the assault failed.

British attack on the Redan on 8th September 1855: Siege of Sevastopol September 1854 to September 1855: picture by Robert Hillingford

The loss of the Malakhov, with its dominant position overlooking Sevastopol and its defences, caused the Russians finally to give up the struggle. The French in the bastion were treated to the view of the Russian garrison crossing the bridges to the north side of the harbour, leaving the city in ruins to the British and French.

In the final attack, the French lost 5 generals killed and 4 wounded. French casualties were 7,567 officers and men. The British lost 2,271 officers and men. 3 British generals were wounded. Russian casualties on the last day of fighting were 12,913. 2 Russian generals were killed and 5 wounded.

On 11th September 1855, the Russians burnt the remaining ships of the Black Sea Fleet. The siege was effectively over. The war did not last much longer.

100,000 Russians are said to have died in the defence of Sevastopol.

British Regiments in the Crimean War: Number of Victoria Crosses awarded:

King’s Dragoon Guards: now the Queen’s Dragoon Guards.

4th Dragoon Guards: later the 4th/7th Royal Dragoon Guards and now the Royal Dragoon Guards.

5th Dragoon Guards: later the 5th Inniskilling Dragoon Guards and now the Royal Dragoon Guards.

6th Dragoon Guards: later the 6th Carabineers and now the Royal Scots Dragoon Guards.

1st Royal Dragoons: now the Blues and Royals.

Royal Scots Greys: now the Royal Scots Dragoon Guards. 2

4th Light Dragoons: later the 4th Hussars, then the Queen’s Royal Irish Hussars and now the Queen’s Royal Hussars. 1

Inniskilling Dragoons: later the 5th Inniskilling Dragoon Guards and now the Royal Dragoon Guards. 1

8th Hussars: later the Queen’s Royal Irish Hussars and now the Queen’s Royal Hussars.

10th Hussars: later the Royal Hussars and now the King’s Royal Hussars.

11th Hussars: later the Royal Hussars and now the King’s Royal Hussars. 1

12th Lancers: now the 9th/12th Royal Lancers.

13th Light Dragoons: later the 13th/18th Royal Hussars and now the Light Dragoons.1

17th Lancers: later the 17th/21st Lancers and now the Queen’s Royal Lancers. 3

Royal Artillery: 9

Royal Engineers: 7

Grenadier Guards: 4

Coldstream Guards: 3

Scots Fusilier Guards: now the Scots Guards. 5

Lieutenant James Lindsay of the Scots Fusilier Guards winning the Victoria Cross at the Battle of Inkerman: picture by Louis Desanges

1st Royal Regiment: later the Royal Scots and now the Royal Regiment of Scotland. 1

3rd Regiment, the Buffs: later the East Kent Regiment and now the Princess of Wales’s Royal Regiment. 2

4th King’s Own Royal Regiment: later the King’s Own Royal Border Regiment and now the Duke of Lancaster’s Regiment. 1

7th Royal Fusiliers: now the Royal Regiment of Fusiliers. 5

Lieutenant William Hope of 7th Royal Fusiiers winning the Victoria Cross by coming to the aid of his adjutant Lieutenant Hobson: Siege of Sevastopol September 1854 to September 1855 in the Crimean War: picture by Louis Desanges

9th Regiment: later the Royal Norfolk Regiment and now the Royal Anglian Regiment.

13th Light Infantry: later the Somerset Light Infantry and now the Rifles.

14th Regiment: later the West Yorkshire Regiment and now the Yorkshire Regiment.

17th Regiment: later the Royal Leicestershire Regiment and now the Royal Anglian Regiment. 1

18th Royal Irish Regiment: disbanded in 1922. 1

19th Regiment: later the Green Howards and now the Yorkshire Regiment. 2

20th Regiment: later the Lancashire Fusiliers and now the Royal Regiment of Fusiliers.

21st Regiment, the Royal Scots Fusiliers and now the Royal Regiment of Scotland

23rd Royal Welch Fusiliers and now the Royal Welsh: 4

Captain Bell of the Royal Welch Fusiliers winning the Victoria Cross at the Battle of the Alma: picture by Louis Desanges

Assistant Surgeon Sylvester of the Royal Welch Fusiliers, winning the Victoria Cross on 8th June 1855 at Sevastopol, by treating his wounded adjutant Lieutenant Dyneley under fire: picture by Thomas Jones Barker

28th Regiment: later the Gloucestershire Regiment and now the Rifles.

30th Regiment: later the East Lancashire Regiment and now the Duke of Lancaster’s Regiment. 1

31st Regiment: The East Surrey Regiment and now the Princess of Wales’s Royal Regiment.

33rd Regiment: later the Duke of Wellington’s Regiment and now the Yorkshire Regiment.

34th Regiment: later the Border Regiment and now the Duke of Lancaster’s Regiment. 2

38th Regiment: later the South Staffordshire Regiment and now the Mercian Regiment.

39th Regiment: later the Dorsetshire Regiment and now the Rifles.

41st Regiment: later the Welsh Regiment and now the Royal Welsh. 2

42nd Royal Highland Regiment, the Black Watch.

44th Regiment: later the Essex Regiment and now the Royal Anglian Regiment. 1

46th Regiment: later the Duke of Cornwall’s Light Infantry and now the Light Infantry.

47th Regiment: later the Loyal North Lancashire Regiment and now the Duke of Lancaster’s Regiment. 1

Private John McDermond of the 47th Regiment winning the Victoria Cross by coming to the aid of his colonel at the Battle of Inkerman in the Crimean War: picture by Louis Desanges

48th Regiment: later the Northamptonshire Regiment and now the Royal Anglian Regiment.

49th Regiment: later the Berkshire Regiment and now the Rifles. 3

50th Regiment: later the Royal West Kent Regiment and now the Princess of Wales’s Royal Regiment.

55th Regiment: later the Border Regiment and now the Duke of Lancaster’s Regiment. 2

56th Regiment: later the Essex Regiment and now the Royal Anglian Regiment.

57th Regiment: later the Middlesex Regiment and now the Princess of Wales’s Royal Regiment. 2

62nd Regiment: later the Wiltshire Regiment and now the Rifles.

63rd Regiment: later the Manchester Regiment and now the Duke of Lancaster’s Regiment.

68th Regiment: later the Durham Light Infantry and now the Light Infantry. 1

71st Highland Light Infantry, later the Royal Highland Fusiliers and now the Royal Regiment of Scotland.

72nd Highlanders: later the Seaforth Highlands, then the Queen’s Own Highlanders then the Highlanders and now the Royal Regiment of Scotland.

77th Regiment: later the Middlesex Regiment and now the Princess of Wales’s Royal Regiment. 2

79th Highlanders, the Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders: later the Queen’s Own Highlanders and now the Highlanders.

82nd Regiment: later the South Lancashire Regiment and now the Duke of Lancaster’s Regiment.

88th Connaught Rangers: disbanded in 1922.

89th Regiment: later the Royal Irish Fusiliers; disbanded in 1922.

90th Regiment: later the Scottish Rifles; disbanded in 1966. 2

93rd Regiment: later the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders and now the Royal Regiment of Scotland. 2

95th Regiment: later the Sherwood Foresters and now the Mercian Regiment.

97th Regiment: later the Royal West Kent Regiment and now the Princess of Wales’s Royal Regiment.

Rifle Brigade: now the Rifles. 7

Corporal Robert Shields of the Royal Welch Fusiliers, winning the Victoria Cross on 8th June 1855 at Sevastopol, by bringing in his wounded adjutant Lieutenant Dyneley: picture by Louis Desanges

Anecdotes and Traditions from the Crimean War:

- The French artist Louis Desanges painted a series of pictures portraying the early winners of the Victoria Cross. Many of Desanges’s pictures were purchased by Lord Wantage who, as Lieutenant Lindsay in the Scots Fusilier Guards, won the VC at the Battle of the Alma. Lord Wantage held the pictures in a Victoria Cross Gallery in Wantage. The gallery passed to the local authority, which allowed the pictures to be inadequately stored in the Second World War and largely lost to damp.

References for the Siege of Sevastopol:

Sir John Fortescue’s History of the British Army

The War in the Crimea by General Sir Edward Hamley

British Battles Volume III by James Grant

The previous battle in the Crimean War is the Battle of Inkerman

The next battle in the British Battles sequence is the Siege of Delhi