The Battle fought between 9th and 13th December 1813; Wellington’s army crossing the River Nive and moving further into France; a battle with some of the fiercest fighting of the Peninsular War

46. Podcast on the Battle of the Nive: fought between 9th and 13th December 1813 in the Peninsular War with Wellington’s army crossing the River Nive and moving further into France; a battle with some of the fiercest fighting of the Peninsular War: John Mackenzie’s britishbattles.com podcasts

The previous battle of the Peninsular War is the Battle of the Nivelle

The next battle in the British Battles Sequence is the Battle of St Pierre

War: Peninsular War

Date of the Battle of the Nive: 9th to 13th December 1813

Place of the Battle of the Nive: In the south-west corner of France near the Spanish border.

Combatants at the Battle of the Nive: British, German, Portuguese and Spanish troops against the French.

Commanders at the Battle of the Nive: General the Earl of Wellington against Marshal Soult.

Lieutenant General Sir Rowland Hill commanded the British, Portuguese and Spanish corps on the north bank of the River Nive that resisted Marshal Soult’s assault at the Battle of St Pierre on 13th December 1813.

Size of the armies at the Battle of the Nive:

Wellington commanded an army of 90,000 British, Portuguese and Spanish troops.

Soult commanded 67,000 French troops.

Winner of the Battle of the Nive: Wellington’s army of British, German, Portuguese and Spanish forced the line of the River Nive in a fiercely fought battle.

Background to the Battle of the Nive:

With the Battle of the Nivelle, Wellington’s army moved out of the Pyrenees Mountains into the area of France bounded by the River Nivelle to the south, the River Adour to the north-east and the Bay of Biscay to the north-west, with the town of Bayonne on the estuary of the River Adour.

The move from snow, wind and rain swept mountainsides to farmland saw desertion levels in Wellington’s army fall dramatically.

With his army on French territory, Wellington was determined the peasantry was not to be alienated by marauding soldiers and exercised rigorous control over his troops.

Many of the Spanish formations that could not be trusted not to loot French farms were moved back across the Spanish border.

Although a significant improvement, the new area was not sufficiently large to accommodate Wellington’s army for long, making further operations an urgent imperative.

Soult’s main position was at Bayonne, with a heavily fortified camp on the south bank of the River Adour, protected by an area of inundation.

The rest of the French army was positioned along the north bank of the River Nive.

The Battle of the Nive:

Wellington received news of Napoleon’s resounding defeat at the hands of the Russians, Prussians and Austrians at the Battle of Leipzig, won on 19th October 1813, as did Marshal Soult.

By the end of October 1813, instructions arrived from London for Wellington to continue his invasion of France, an advance he was already planning.

On 11th November 1813 heavy rainfall struck the region ruling out offensive operations for the time being.

As at the Battle of the Nivelle, the improvement in the weather on 19th November 1813 put Soult on the alert that he might be attacked.

However, the rains resumed and did not abate until 8th December 1813, when Wellington was enabled to put his offensive plans into operation.

The strength of Soult’s entrenched position around Bayonne, behind extensive inundation of the area, made a direct assault impracticable.

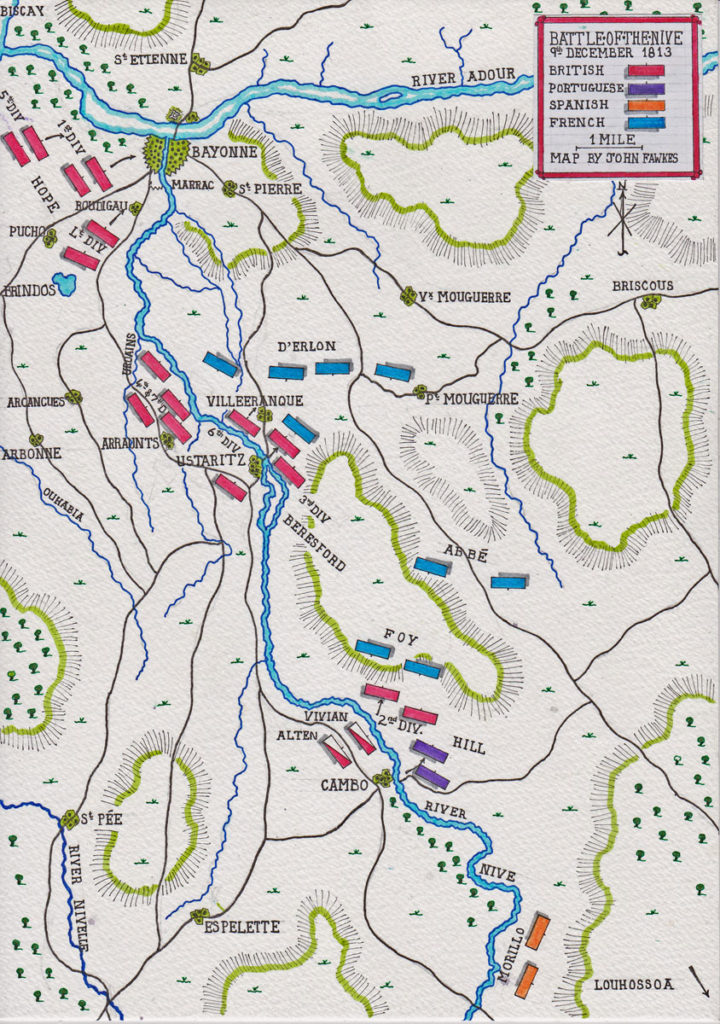

Wellington’s attack would be across the River Nive to the south-east of Bayonne.

The crossing of the River Nive would be accomplished by General Hill’s corps, crossing the river at Cambo, with the British Second Division, the Portuguese Division, Vivian’s and Victor Alten’s brigades of cavalry and Ross’s horse artillery troop.

Hill would advance west towards Bayonne and occupy a position 2 miles long, running east from Villefranque to Petit Mouguerre.

Beresford would support Hill by bridging the River Nive at Ustarits and crossing to the north bank with the British Third and Sixth Divisions.

In addition, further down the River Nive, the British Seventh and Fourth Divisions would move to the vicinity of Arrauntz and be ready to cross the river as additional support for Hill.

The Spanish General Morillo was to prevent the French at Louhassa from taking Hill in the rear.

Soult’s attention would be kept on Bayonne by a feint attack mounted by Hope with the British First and Fifth Divisions and the Light Division at Arcangues.

Soult was expecting a crossing of the River Nive and brought forward his two divisions of dragoons, one commanded by his brother, Pierre Soult, to cover the withdrawal of the French troops in Louhossoa.

Soult’s intention was to wait until Wellington’s forces were divided, with part on each side of the River Nive and then launch an attack on one or the other.

Wellington’s preparations were put in place on the night of 8th December 1813, with Beresford’s pontoon bridges laid across the River Nive.

In the early hours of 9th December 1813, a bonfire on a hill at Cambo gave the signal for the operation to begin.

The Sixth Division crossed the River Nive at Ustarits, driving back the French piquets, finalising the pontoon bridges and capturing a wooden bridge in addition.

Crossing the river, the Sixth Division drove Gruardet’s Brigade of Damargnac’s Division to Villefranque.

Hill crossed the River Nive higher up at Cambo and at two points downstream with little difficulty, even though the stream was running high due to the previous heavy rains.

Foy’s Division was guarding this section of the River Nive and fell back, contesting the ground vigorously, Foy’s two brigades withdrawing to Petit Mouguerre and Vieux Mouguerre.

Abbé’s Division moved forward to support Foy.

Berlier’s Brigade was forced to make a considerable detour to the east to reach Foy.

Hill was not able to follow Foy up as quickly as Wellington’s plan required, due to the saturated condition of the ground. He was only ready to move forward along the road from Loursinthoa towards Bayonne at around 3pm.

By this time, the whole of D’Erlon’s corps was deployed between Villefranque and Petit Mouguerre.

At 3pm, Madden’s Portuguese Brigade from Clinton’s Sixth Division drove the French brigade of Darmargnac’s Division out of Villefranque, after an initial repulse.

The descent of thick fog at the end of the afternoon brought fighting to an end.

On Wellington’s left flank, on the sea coast, in front of Bayonne, Hope’s British First Division marched up to the Heights of Barouillet and halted.

The British Fifth Division came up on the coast on the left.

Hope’s force wheeled to the right and advanced, pushing the French back to the edges of the Bayonne entrenchments.

On Hope’s right, the British Light Division pressed forward, also pushing the French troops it faced to the edge of the Bayonne entrenchments.

These positions enabled Wellington to make a detailed reconnaissance of the Bayonne entrenchments, assessing their vulnerability to an attack across the River Adour estuary.

At nightfall, Hope’s two divisions and the Light Division fell back to their previous quarters.

For the Foot Guards, this involved an exhausting march back to St Jean de Luz.

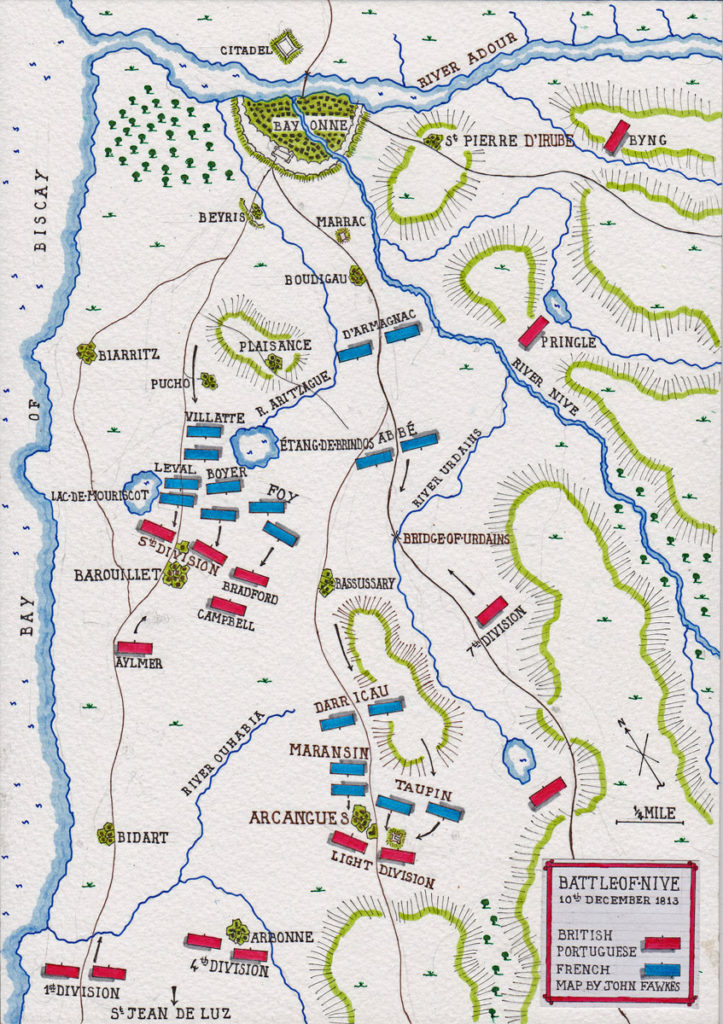

The Battle on 10th December 1813:

Soult now believed he had an opportunity to inflict a significant defeat on Wellington, with the British, Portuguese and Spanish forces deployed on either bank of the River Nive.

Fortescue considers that Wellington was not sufficiently aware of the danger he faced, underestimating the ability of the French to take the initiative.

At midnight on 9th December 1813, D’Erlon’s Corps, comprising the divisions of Foy, Darmagnac, Abbé and Darricau, withdrew from their positions to the south-east of Bayonne, marched towards the town and crossed the River Nive above Bayonne to the entrenched camp at Marrac.

From Marrac, D’Erlon’s divisions were to support the divisions of Taupin and Maransin, commanded by Clausel, in the forthcoming attack on the left wing of Wellington’ army.

These two divisions assembled at Boudigau, ¼ mile south of Marrac, with engineers and a battery, ready to begin the French attack.

On their right flank, the divisions of Leval and Boyer would advance from the entrenchments at Beyris.

Reille was instructed to lead his divisions, Leval’s and Boyer’s, to the heights at Plaisance, while Clausel advanced west through the gap between the River Nive and the River Aritzague.

Vilatte’s division remained in reserve behind Marrac.

For his attack, Soult concentrated nine infantry divisions, Sparre’s Dragoon Division and 40 guns.

On Wellington’s side there was no expectation of a French attack.

Following the previous day’s action, the First Division and Aylmer’s Brigade had returned to St Jean de Luz, twelve miles from the line of contact between the two sides.

The Fifth Division and Bradford’s Portuguese Brigade occupied the heights of Barrouillet and Bidart, with outposts from the Portuguese 8th Caçadores by Lake Mouriscot.

Wellington’s orders for trenches to be dug before Barrouillet and Bassussary had so far led only to a few abatis being constructed.

The British Light Division was positioned in Wellington’s centre, at Arcangues, but was under orders to fall back to Arbonne, a mile to the west-south-west.

The Light Division piquets occupied positions on three salient spurs between the eastern end of the Lac de Brindos and the junction of the River Urdains with the River Nive.

One brigade of the British Seventh Division filled the position on the right of the Light Division, between it and the River Nive at Urdains Bridge.

The second Seventh Division brigade was 3 miles to the rear, behind Ste. Barbe’s Hill.

The British Fourth Division was further to the rear in the forest of St Pée.

Of the British commanders, Hope was at St Jean de Luz and Wellington, Hill and Beresford were on the far side of the River Nive, preparing for a further advance on Bayonne.

Heavy rain fell in the night, delaying the French concentration for the attack.

In addition, there was an alteration to the French deployment, with Foy’s Division transferred to Reille’s command at Beyris.

At daybreak, the British Light Division forward picquets saw the French light troops assembling, albeit in a nonchalant manner; to the experienced officers a characteristic sign that they were about to attack.

Marshal Soult was seen in the area.

Alten, commander of the British Light Division, cancelled the order to withdraw to Arbonne and warned the Light Division to prepare for battle.

The attack on the Light Division’s forward positions began at 9.30am, with advancing French skirmishers enveloping the division’s piquets and taking several prisoners.

Alten formed his division around the church and chateau of Arcangues.

The churchyard was held by the 43rd Light Infantry, the walls providing protection against French cannon fire.

The chateau, also protected by a network of thick walls, was held by the 1st and 3rd Battalions of the 95th Rifles.

The 52nd Light Infantry and the rest of the Light Division was formed in the left rear of these two strongpoints.

Clausel brought up guns to cannonade the church, but his gunners were hampered by the fire of the British light infantrymen and all assaults by his infantry were easily repelled.

To the east, Abbé’s Division attempted an attack on the brigade of the Seventh Division holding Urdains Bridge, but were driven off, with the British suffering no casualties.

During the day’s fighting, four French divisions, Taupin’s, Maransin’s, Abbé’s and Darmagnac’s, held by the Light Division and an additional brigade, achieved nothing.

No attempt was made to outflank Alten’s Light Division by an advance into the valley of the River Ouhabia.

Fortescue describes the efforts of the left wing of Soult’s attack as ‘slow, feeble and unenterprising’.

The French attack by Soult’s right wing was more determined.

Following the beginning of Clausel’s attack on the Light Division, Leval’s Division advanced down the Great Road, that runs along the coast, towards Barouillet. Boyer’s Division marched on Pucho.

Foy’s Division, transferred from Clausel to Reille, came up in line.

The French advance met a determined defence by Campbell’s Portuguese Brigade (4th Caçadores and 1st and 16th Portuguese) in the defile between the lakes of Mouriscot and Brindos, which gave Hay time to bring up Robinson’s Brigade from his Fifth Division (1st/4th, Prov. Bn. of 30th and 44th, 2nd/47th, 2nd/59th Regiments and 1 Co. of Brunswick Oels) to positions before the village of Barrouillet.

Boyer’s Division attacked Barrouillet in column of battalions from the north, while Foy’s Division mounted an assault from the east, with Leval’s Division in reserve.

In confused fighting in the woods and hedged fields before Barrouillet, much of it around the isolated ‘Mayor’s House’, the French were driven back.

British and Portuguese battalions were now arriving from the direction of St Jean de Luz, enabling a second brigade to join the troops in Barrouillet.

Soult launched a second attack along the Great Road, attempting to bypass Barrouillet, but by this time more British and Portuguese troops had come up.

Three French brigades, Montfort’s, Gauthier’s and Berlier’s, each from a separate division, attacked in line down the Great Road, but met Aylmer’s Brigade (76th, 2nd/84th and 85th Regiments) and Bradford’s Portuguese (5th, 13th and 24th Regiments) coming up to meet them.

The French formations dissolved under the attack on their flanks and in front and fell into headlong retreat, with many prisoners taken.

The time was 2pm. The British First Division was within sight, coming up from St Jean de Luz.

Soult sent Foy’s second brigade to pass Barouillet by the valley of the River Ouhabia, while the German brigade of Villatte’s Division replaced it in support of the attack.

On the line of the River Nive, Wellington was crossing to the left bank with the British Third and Sixth Divisions.

Dalhousie’s second brigade moved west to fill the gap between Urdains and the Light Division, while the Third Division held Urdains and the bridge.

Cole’s Fourth Division moved up in support of the Light Division, with one brigade covering the gap on its left, thereby frustrating Soult’s last attempt on Barrouillet.

With the fall of night Foy and Vilatte fell back to Pucho, Boyer to Plaisance, while Leval’s Division remained before Barrouillet.

Clausel held the positions he had taken from the Light Division.

As the French formations withdrew, three German regiments in Napoleon’s service managed to hang back. Once clear of the French ranks, these German regiments surrendered by a secret prior arrangement. They were marched to the rear and given ship to Hamburg.

The loss of the German regiments was a considerable blow to Soult, forcing him to disarm his remaining German troops. He thereby lost some 1,200 men.

Soult’s attack brought home to Wellington the vulnerability of his position, with his army divided into sections on either side of the River Nive, particularly at a time of the year when sudden heavy downfalls of rain significantly raised the level of the river and damaged pontoon bridges.

Two new pontoon bridges across the River Nive were under construction at Ustarits, but only one was ready by 10th December 1813.

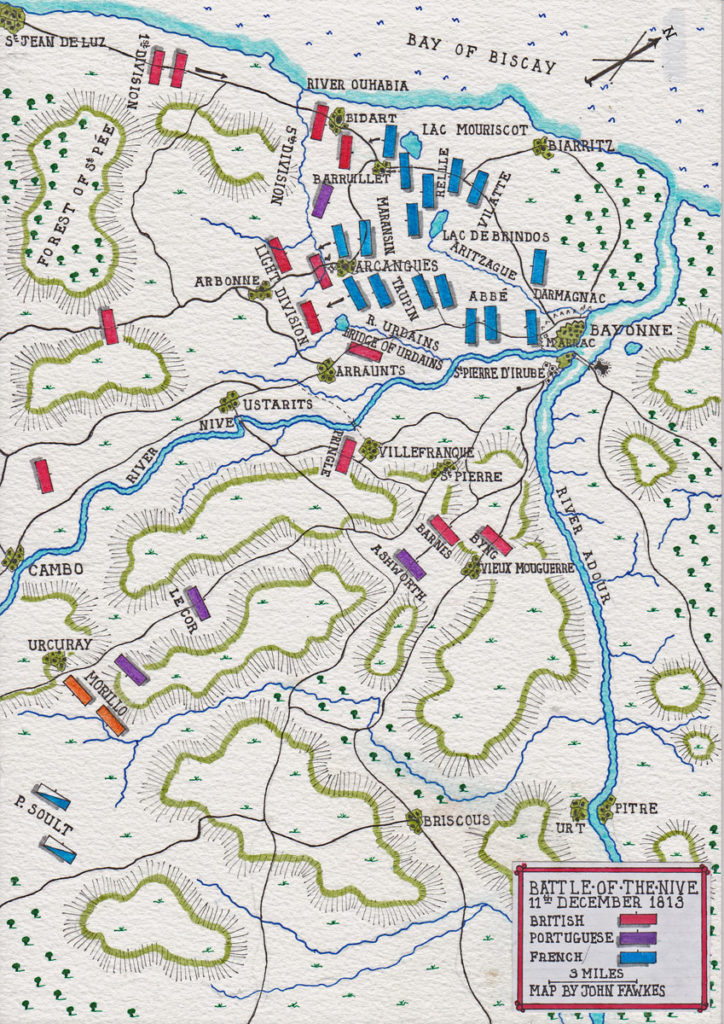

The renewed Battle of the Nive on 11th December 1813:

There was dense fog around Barouillet on the morning of 11th December 1813 as Wellington rode up from St Jean de Luz.

The French piquets withdrew towards Bassussary, leaving the British and Portuguese free to resume their original positions.

At around 10am the British 9th Regiment conducted a reconnaissance towards Pucho.

On entering Pucho, the 9th was heavily attacked, suffering around 100 casualties and had to be extracted by Portuguese infantry.

On the assumption that the French offensive in the area was ended, Wellington rode east to the banks of the River Nive to check on the bridges.

Rations were issued and Hope’s troops permitted to disperse and gather firewood, after their chilly morning march.

However, this was a rash move as in the early afternoon the French resumed their attack on Barrouillet.

Boyer’s Division marched up the Great Road, with Foy’s Division on its left flank.

Shortly after 2pm, Boyer’s Division launched its attack on Barrouillet, seizing the Mayor’s House and other areas of the village, while the British and Portuguese infantry hurriedly assembled.

There was then wild and confused fighting, with Sir John Hope personally rallying his men.

In the midst of the struggle, a British battalion fired into the French flank, while the Fifth Division, part of Aylmer’s Brigade and the Portuguese formed the first line from Lake Mouriscot, across the front of the Mayor’s House and into the valley of the River Ouhabia.

The British Foot Guards and the rest of Aylmer’s Brigade formed the second line.

The French attack was beaten off, their infantry withdrawing to their original advanced posts, leaving their artillery to continue firing into Barrouillet for the rest of the day.

Clausel’s Divisions remained in front of the British Light Division positions, without firing a shot and D’Erlon’s single division remained stationary, to their east, while Wellington’s bridge building continued.

By the evening of 11th December 1813, Wellington’s new bridge was completed, opposite Villefranque, easing the problem of moving troops from one side of the River Nive to the other.

On the morning of 12th December 1813, a visit by Pakenham, Wellington’s Adjutant-General, to the British advanced piquets caused the French to expect an attack. A heavy fire broke out from each side and continued for the rest of the morning, inflicting casualties, 100 on the British side.

The final day of the Battle of the Nive, on 13th December 1814, took place in the Battle of St Pierre, the next entry on britishbattles.com.

Casualties at the Battle of the Nive:

French losses on the first day of fighting, 9th December 1813, were probably around 900 killed, wounded and taken prisoner. Half of these casualties were suffered by the divisions of Boyer and Leval, facing Hope.

British, German and Portuguese casualties were about the same as the French, the Portuguese suffering half of the number.

The French lost 69 guns.

French casualties on the 10th December 1813, in the fighting west of the River Nive, were probably around 2,000, although Soult admitted to only 1,000 casualties.

The 39th and 65th Regiments of Foy’s Division suffered over 300 killed and wounded in the attack on the Mayor’s House outside Barouillet.

British and German casualties were probably around 600 killed, wounded and taken prisoner.

Portuguese casualties were probably around 1,000.

The British regiments that suffered the most were the 9th, 47th and 59th from Hay’s Fifth Division.

The Aftermath to the Battle of the Nive:

The immediate consequence of the battle was that the French army was shut up in Bayonne.

Medal and Battle Honour for the Battle of the Nive:

The Military General Service Medal 1848 was issued to all those serving in the British Army present at specified battles during the period 1793 to 1840 who were still alive in 1847 and applied for the medal. The medal was only issued to those entitled to one or more of the clasps. There were 21 clasps available for service in the Peninsular War.

The Battle of the Nive was one of the clasps.

The battle honour ‘Nive’ was awarded to the following regiments: 16th Light Dragoons, 1st, 2nd and 3rd Foot Guards, 1st, 3rd Buffs, 4th King’s Own, 9th, 11th, 28th, 31st, 32nd, 34th, 36th, 38th, 39th, 42nd Royal Highland Regiment, 43rd Light Infantry, 47th, 50th, 52nd Light Infantry, 57th, 59th, 60th Rifles, 61st, 66th, 71st Highland Light Infantry, 76th, 79th Cameron Highlanders, 84th, 85thLight Infantry, 87th, 91st Highlanders, 92nd Gordon Highlanders and 95th Rifles.

The award of a battle honour seems not to have been governed by any particularly reliable benchmark. In some instances, regiments were not given a battle honour when they were present and suffered casualties.

Anecdotes and traditions from the Battle of the Nive:

- Richard Gubbins, who fought as a captain in the 85th Duke of York’s Light Infantry, was the brother-in-law of the artist John Constable. Gubbins was promoted captain into the 85th from the 24th, to avoid being posted to India with the regiment’s 2nd Battalion. Gubbins was one of the officers selected by the Duke of York for the 85th on the regiment being designated with his name. Gubbins’ portrait, shown above, was painted by his famous brother-in-law.

References for the Battle of the Nive:

See the extensive list of references given at the end of the Peninsular War Index.

46. Podcast on the Battle of the Nive: fought between 9th and 13th December 1813 in the Peninsular War with Wellington’s army crossing the River Nive and moving further into France; a battle with some of the fiercest fighting of the Peninsular War: John Mackenzie’s britishbattles.com podcasts

The previous battle of the Peninsular War is the Battle of the Nivelle

The next battle in the British Battles Sequence is the Battle of St Pierre