The battle in Cornwall that was a personal triumph for King Charles I, fought from 11thAugust to 2nd September 1644

The previous battle in the English Civil War is the Battle of Marston Moor

The next battle in the English Civil War is the Second Battle of Newbury

To the English Civil War index

Battle: Lostwithiel

War: English Civil War

Date of the Battle of Lostwithiel: 11th August to 2nd September 1644

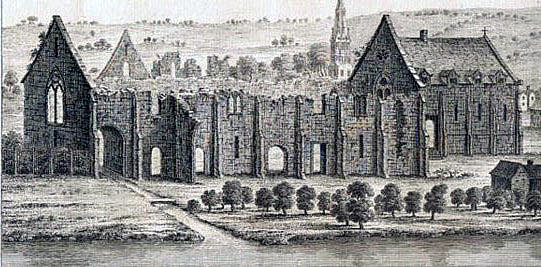

Duchy Palace at Lostwithiel: Battle of Lostwithiel 11th August to 2nd September 1644 in the English Civil War

Place of the Battle of Lostwithiel: Lostwithiel on the south coast of Cornwall.

Combatants at the Battle of Lostwithiel:

The Royalist forces of King Charles I against the forces of Parliament.

King Charles I: Royalist Commander at the Battle of Lostwithiel 11th August to 2nd September 1644 in the English Civil War: engraving by Wenceslaus Hollar

Generals at the Battle of Lostwithiel: King Charles I commanded his army in person and conducted the short successful campaign.

Robert Devereux, 3rd Earl of Essex commanded the Parliamentary Army but left his subordinate commanders Sir William Balfour of the cavalry and Sergeant-Major-General Philip Skippon of the Foot with considerable discretion, finally escaping by sea and leaving Skippon in command.

Size of the armies at the Battle of Lostwithiel:

Several Royalist forces combined for the Lostwithiel campaign: The King’s main army from Oxford, Prince Maurice’s, Sir Ralph Hopton’s and Sir Richard Grenvile’s forces. The King’s eventual force probably comprised around 6,000 Horse and Dragoons and some 10,000 Foot.

The Earl of Essex was led to expect significant recruiting for the Parliamentary side in Cornwall which did not occur. His army in Lostwithiel probably comprised around 3,000 Horse and Dragoons and around 7,000 Foot. He lost some 45 guns in the campaign.

Winner of the Battle of Lostwithiel: King Charles I won a striking victory at Lostwithiel with the flight of the Parliamentary Commander the Earl of Essex and the surrender of the Parliamentary Army, less its cavalry which escaped led by Sir William Balfour.

Robert Dereux, 3rd Earl of Essex, Parliamentary Commander at the Battle of Lostwithiel 11th August to 2nd September 1644 in the English Civil War: engraving by Wenceslaus Hollar

Uniforms, arms and equipment at the Battle of Lostwithiel:

See this section in the Battle of Edgehill.

Background to the Battle of Lostwithiel:

The origins of the English Civil War are dealt with under this section in the Battle of Edgehill.

At the beginning of 1644 the army of the Scots Covenanters invaded the north of England in alliance with the English Parliament. This Scots invaders, joining the Parliamentary armies of Lord Fairfax and the Earl of Manchester forced the Royalists commanded by the Earl of Newcastle onto the defensive, eventually putting them under siege in the City of York.

In the South of England, the Royalist Army of Prince Maurice, after taking a number of towns in Hampshire, Dorset and Devon began the siege of the important Parliamentary port of Lyme (now Lyme Regis).

King Charles I left Oxford with his army and, after a pursuit by the armies of the Earl of Essex and Sir William Waller on 29th June 1644 fought Sir William Waller at the Battle of Cropredy Bridge, defeating Waller and ruining his army.

Leaving Sir William Waller to deal with King Charles I’s army the Earl of Essex, on receipt of instructions from Parliament to relieve Lyme marched to the South-West.

Essex’s entry into Dorset caused Prince Maurice to abandon his siege of Lyme Regis and retreat to the west. This completed Essex’s instructions, but Essex was persuaded by one of his senior officers Lord Robartes that if he took his army into Cornwall he could expect recruits to come forward in considerable numbers in support of the Parliament, enabling him to conquer the whole south-west of English from the Royalists.

On 19th June 1644 Essex convened a council of war at Weymouth. The council supported Essex’s plan to continue to march west. The council’s advice was reported to the Parliament in London causing Parliament to confirm that Essex should continue his march to the west to prevent Prince Maurice from raising forces there for the Royalist cause.

Sir William Balfour, Parliamentary Cavalry Commander at the Battle of Lostwithiel, 11th August to 2nd September 1644 in the English Civil War: a contemporary engraving by an unknown artist

King Charles I after fighting the Battle of Cropredy Bridge and receiving news of the Royalist defeat at Marston Moor, but not yet realising the extent and disastrous consequences of Marston Moor marched his Royalist Army to the West Country.

On 23rd July 1644 Essex’s army reached Tavistock in Devon, forcing the Royalist Commander Sir Richard Grenvile to lift his siege of Plymouth and withdraw into Cornwall, taking up a position on the Tamar River at Horsebridge.

On 26th July 1644, as the King’s Army reached Exeter Essex crossed the Tamar into Cornwall forcing the withdrawal of Grenvile’s small force.

From then King Charles I forced the pace, reaching the Cornish town of Launceston as Essex marched into Bodmin.

Essex was finding that far from welcoming the forces of Parliament the country folk of Cornwall were actively hostile and that in addition to the King’s army Prince Maurice’s, Sir Ralph Hopton’s and Sir Richard Grenvile forces were converging on him.

Essex marched south to Lostwithiel from where he could through the port of Fowey make contact with the fleet, entirely in the hands of Parliament and commanded by the Earl of Warwick.

As the Royalist Army prepared for battle sweeping changes were made in its senior ranks.

On 8th August 1644 the Royalist Lieutenant-General of Horse Lord Wilmot was arrested at the head of his troops for high treason and sent under escort to Exeter. Lord Goring newly arrived from Prince Rupert’s army after the Battle of Marston Moor was appointed in Wilmot’s place.

Sir Ralph Hopton was given command of the Royalist Artillery in place of Lord Henry Percy, a close associate of Lord Wilmot.

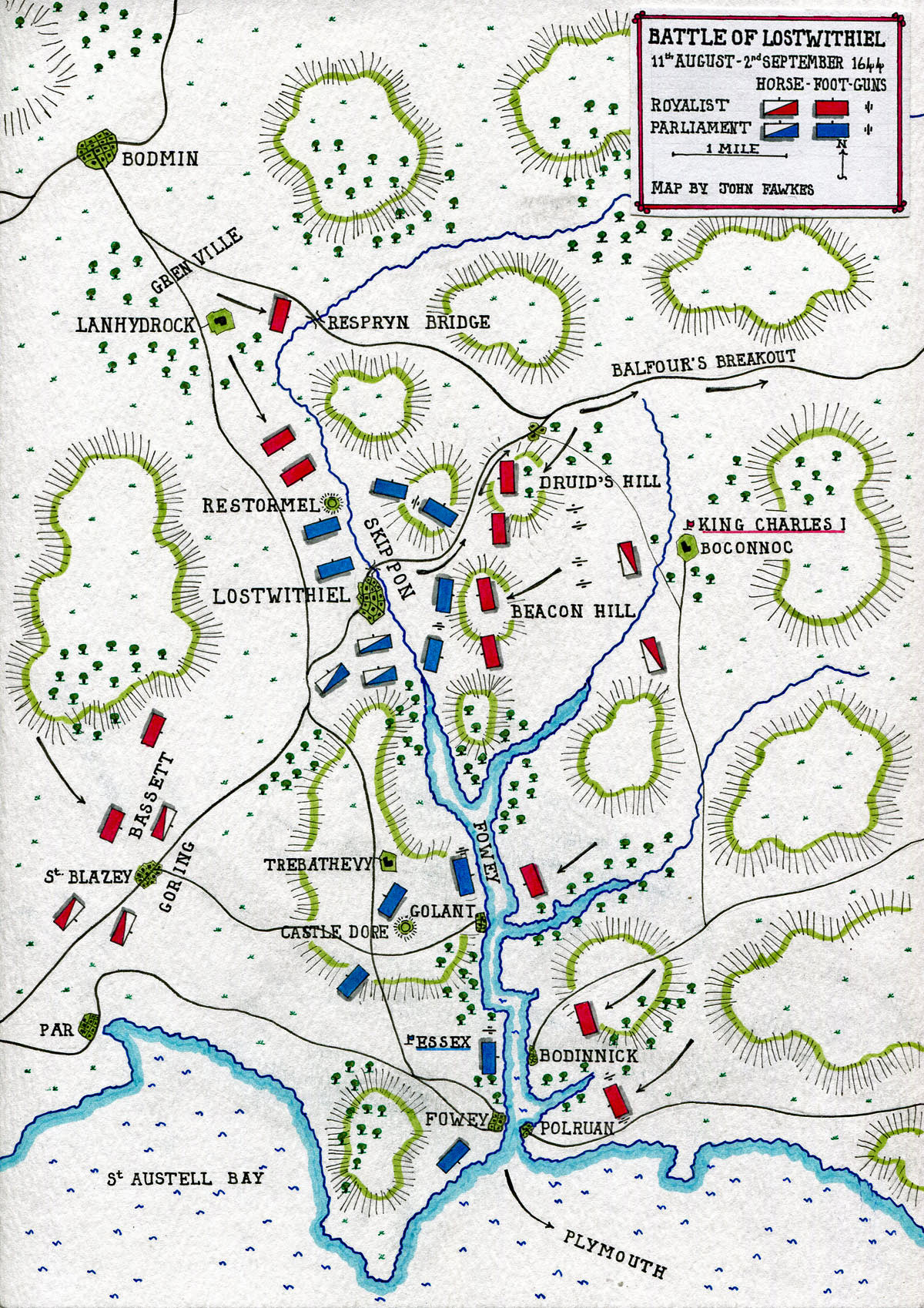

Map of the Battle of Lostwithiel 11th August to 2nd September 1644 in the English Civil War: map by John Fawkes

Account of the Battle of Lostwithiel:

The Parliamentary Army took up positions around Lostwithiel. Essex dispatched a contingent of Foot to hold Fowey Town and await the arrival of Warwick’s ships. Essex stationed the rest of his Foot on the east side of the Fowey River, around the high ground of Beacon Hill, and on the west side of the river at Restormel Castle to the north.

The Parliamentary Horse covered the army’s flanks and patrolled the areas between the two main detachments of Foot.

On 11th August 1644 the Royalist Commander Sir Richard Grenvile occupied Bodmin and marched south to take Respryn Bridge enabling him to have immediate contact with King Charles I’s Army on the east bank of the Fowey River. Grenvile then moved on to Lanhydrock.

On 13th August 1644 Lord Goring and Sir Jacob Astley advanced south down the east bank of the Fowey River as far as the coast and the next day garrisoned Polruan fort with 200 foot and some guns, which effectively shut off access to the Fowey Estuary for the Parliamentary Fleet and left detachments to guard Boddinnick Ferry and the ground opposite Golant.

The Earl of Essex was hoping for assistance from his old Parliamentary Rival Sir William Waller. General Sir John Middleton was marching with a force of Horse and Dragoons from Waller’s army to reinforce Essex but was turned back from Bridgewater by a Royalist force under Sir Francis Doddington.

The rest of Waller’s army no longer constituted a reliable fighting force after its defeat at the Battle of Cropredy Bridge.

Cavaliers’ Encampment: Battle of Lostwithiel 11th August to 2nd September 1644 in the English Civil War

King Charles established his headquarters at Boconnoc to the north-east of Lostwithiel and on 17th August rode down the ‘fair walk’ along the east bank of the Fowey River at Bodinnick Ferry examining the Parliamentary positions on the west bank of the river.

Parliamentary guns fired on the royal party, killing a fisherman standing nearby but without disconcerting the King.

The Battle of Beacon Hill:

King Charles I’s Royalist Army launched its attack on 21st August 1644 from its positions from Lanhydrock to Boconnoc. The assault began at 7am through the early morning mists.

On the west bank of the Fowey River Sir Richard Grenvile advanced on the Parliamentary position in Restormel Castle. Colonel John Weare’s Devonshire Regiment of Foot hastily abandoned the castle.

On the east bank of the Fowey River the Royalist attack captured Beacon and Druid Hills. Prince Maurice advanced with a column across the Liskeard Road and took the prominent hill on the far side.

By nightfall the Royalists were established along the hillsides overlooking the town of Lostwithiel.

During the night of 21st August the Royalist troops built a redoubt on Beacon Hill, brought up their guns and opened fire from the redoubt across the river into the town.

Parliamentary activity over the next days died away causing the Royalists to deduce that Essex’s army had withdrawn towards Fowey Town. Acting on this assumption the King sent half his mounted force across the Respryn Bridge to support Sir Richard Grenvile in an advance on Lostwithiel down the west bank of the Fowey River.

As this advance began it became clear that the Parliamentary forces were still in Lostwithiel in strength and Grenvile’s attack was halted on the King’s order.

On 26th August Lord Goring with 2,000 Horse and Sir Thomas Bassett with a force of Foot marched in a south-westerly direction to St Blazey to shut in Essex’s army still further and to prevent supplies reaching it from the coast. Detachments from this force took St Austell and the coastal village of Par four miles from Fowey Town.

Essex’s Parliamentary Army was now confined to the strip of land from Lostwithiel down the west bank of the Fowey River to Fowey on the coast, two miles wide and two miles long.

On the same day a substantial Royalist supply train reached the King’s army from Dartmouth replenishing the army’s ammunition reserves with 1,000 barrels of gunpowder.

In contrast Essex’s Parliamentary Army was short of food and ammunition. Warwick’s Fleet was prevented from sailing down the Channel to the Fowey Estuary by persistent westerly winds. Essex realized his army’s days were numbered.

During the evening of 30th August 1644 Sir Richard Grenvile learned from Parliamentary deserters that Essex intended a major move with his cavalry breaking out to the east while the remaining Foot and guns with a small mounted force withdrew to Fowey Town.

The King’s forces were immediately alerted with orders to attack any Parliamentary troops trying to escape.

A cottage on the Lostwithiel to Liskeard road was fortified and garrisoned by fifty Royalist musketeers to prevent the passage of any Parliamentary cavalry along the road to the east.

Royalist horse at Saltash were ordered to break down the bridge over the Tamar River.

Break-out of the Parliamentary Horse: Battle of Lostwithiel 11th August to 2nd September 1644 in the English Civil War

At 3am on 31st August 1644 Sir William Balfour broke out of Lostwithiel with the majority of the Parliamentary Cavalry, some 2,000 men, riding across the bridge over the Fowey River and setting off up the road to Liskeard. Balfour achieved complete success crossing the Tamar River by ferry and reaching Plymouth with his force largely intact. No musketeer in the cottage fired a shot. Some Royalist guns hearing the commotion on the Liskeard Road discharged a few rounds with no effect.

Major-General Philip Skippon, Parliamentary Commander at the Battle of Lostwithiel 11th August to 2nd September 1644 in the English Civil War

The next morning the Earl of Cleveland set off in pursuit of Balfour with the 500 men of his Brigade of Horse but was too late to catch him.

On the morning following the escape of Balfour’s Horse the Parliamentary Foot and guns marched out of Lostwithiel to the south.

Major-General Philip Skippon commanded the Parliamentary rearguard whose colours King Charles I could see on the high ground to the south of Lostwithiel from Beacon Hill.

The King ordered his army forward. At 7am a thousand musketeers stormed the bridge over the Fowey River into Lostwithiel preventing its destruction by a Parliamentary party and driving the few remaining troops out of the town.

Royalist guns were brought through Lostwithiel and opened fire on Skippon’s rearguard. Skippon’s troops fell back pressed by Royalist attacks that drove them from field to field heading south.

The Battle of Castle Dore:

While the main body of the Royalist Foot was advancing south through the town of Lostwithiel towards Fowey Town King Charles I led his Regiment of Life Guards from Beacon Hill to the Fowey River and crossed to the west bank by a ford situated to the south of Lostwithiel, meeting Sir Thomas Grenville’s Cornish troops leading the Royalist advance from the town.

The Royalists encountered evidence of the disorderly Parliamentary retreat in an abandoned wagon loaded with muskets and five cannon left in different places, two of them sizeable pieces.

The Parliamentary Foot made a more determined stand immediately to the north of Fowey Town forcing the Cornish Royalists to fall back.

The Royalist Foot rallied under the leadership of Lieutenant-Colonel William Leighton of the King’s Regiment of Life Guard of Foot in the fields to the west of Trebathevy Farm.

King Charles launched his mounted Life Guard in a counter-attack and the Parliamentary Foot were beaten back through several fields driven from the hedgerows by the mounted Cavaliers, in spite of a heavy musketry.

The Royalist Foot caught up with the mounted advance at around 2pm and the rest of the day was spent in what Clarendon calls ‘several smart skirmishes’.

Sir Thomas Basset arriving from St Blazey attacked the Parliamentary left flank, while Colonel Appleyard led the van of the main Royalist army in the assault from Lostwithiel, pushing the Parliamentary Foot back towards Fowey Town.

At 4pm Essex launched his remaining force of mounted troops with the support of his own regiment of Foot in a counter-attack, driving back the Royalist troops and capturing two Royalist colours, until the King’s Life Guard came up and the Parliamentary counter-attack fell back.

Lord Goring arrived with his force of cavalry from St Blazey and was ordered to continue on across the battlefield and join the pursuit of Sir William Balfour’s Parliamentary Horse to the east.

In the early evening Skippon launched his final attempt to stem the Royalist advance with a counter attack from Castle Dore, an Iron Age fort. Over the next hour the Royalists were driven through two fields but then pushed the Parliamentary troops back to Castle Dore.

Spencer Compton 2nd Earl of Northampton: Battle of Lostwithiel 11th August to 2nd September 1644 in the English Civil War

The Earl of Northampton’s Brigade of Horse came up and joined the Royalist assault.

The onset of night brought the Royalist advance to a halt.

The Earl of Essex made off to Fowey Town where he resolved to leave his army by small boat to Plymouth and then to London taking his personal staff and Lord Robartes who had originally urged the incursion into Cornwall. Skippon was left in command of the Parliamentary Army but with no clear instructions.

Skippon commanded five regiments of Foot at Castle Dore spread along a line to the west and east of the castle. The morale of the Parliamentary Foot was sinking fast and during the night many of the troops deserted their posts.

King Charles I spent the night in the field among his men. At times Parliamentary guns were fired in the King’s direction but without effect.

There was little activity on the next day 31st August 1644. The Royalists knew it was simply a matter of time before the trapped Parliamentary force requested terms and the King was reluctant to spill more of his subjects’ blood even rebels.

On 2nd September 1644 Skippon’s Parliamentary Army surrendered and was permitted to march away after handing over 42 guns, 100 barrels of gunpowder and 5,000 muskets and pikes.

Casualties at the Battle of Lostwithiel:

The casualties during the Lostwithiel campaign are hard to assess. Balfour lost around 200 men during his break out to Saltash and crossing the Tamar River into Devon. The remainder of Essex’s Parliamentary Army left in Lostwithiel probably suffered some 500 in killed, wounded and captured before surrendering on 2nd September 1644 and being permitted to march to Southampton. The 6,000-man force probably suffered up to 50% desertions during that march.

All the Parliamentary artillery of some 45 guns was lost to the Royalist Army, either abandoned during the withdrawal from Lostwithiel to Castle Dore or handed over under the terms of the surrender.

Royalist casualties were probably around 500 killed or wounded. All captured Royalists were given up under the terms of the surrender.

Follow-up to the Battle of Lostwithiel:

A Royalist force escorted the surrendered Parliamentary troops as they marched to Southampton, but they were thoroughly plundered on their way, particularly by the locals. The justification given, as in every such case during the Civil War, was that the Parliamentary troops carried loot seized from the locality.

The Lostwithiel campaign, although in the end of no significance in deciding the outcome of the Civil War, showed King Charles I at his best. The King fought a resourceful battle and showed great personal bravery, sharing the hardships of his soldiers in the field and acting with great restraint towards the beaten Parliamentary Army, considering them to be still his subjects and deserving of his consideration in conserving their lives.

In the two battles of Cropredy and Lostwithiel King Charles I’s Royalist Armies destroyed the two main southern Parliamentary Armies. Unfortunately for the Royalists the Parliament was well able to overcome these substantial setbacks.

Lord Wilmot, Royalist Commander at the Battle of Lostwithiel, 11th August to 2nd September 1644 in the English Civil War

Anecdotes and traditions from the Battle of Lostwithiel:

- The reason for Lord Wilmot’s arrest on 8th August 1644 was his unauthorised contact with the Earl of Essex with a proposal for peace. This contact was reported to King Charles I by Lord Digby. Wilmot remained in custody until his release was secured by his patron the Queen. Wilmot was restored to favour and accompanied the Prince of Wales on his escape following the Battle of Worcester.

- Clarendon blamed Lord Goring for the break out by Sir William Balfour with the Parliamentary Horse saying: ‘The notice and orders (from the King to watch for and intercept the escaping Parliamentary Horse) came to Goring when he was in one of his jovial exercises. He received them with mirth, slighting those who sent them as men who took alarms too warmly, and he continued his delights till all the enemy horse were passed through his quarters, nor did he pursue them at any time. Excepting such who by the tiring of their horses became prisoners…’ Peter Young points out that Goring was at St Blazey well to the west of Lostwithiel when Sir William Balfour broke out to the east and could not have acted to contain the Parliamentary Horse. Young states that the distribution of the Royalist forces around Lostwithiel from Polruan to Par while necessary to prevent supplies reaching the Parliamentary army made it difficult to block a determined break-out by a large force of cavalry.

- In the forefront of the charge by the King’s Life Guard at Trebathevy Farm was Captain Edward Brett leading the Queen’s Troop. Brett was shot in the left arm at the beginning of the attack but continued to lead his men driving the Parliamentary Foot before them. As he returned from the charge to seek treatment for his arm King Charles I called him over and drawing Brett’s sword knighted him from the back of his horse. Brett was promoted major. After the English Civil War Brett took service with William of Orange and died in 1683 aged 75 years then holding the post of Sergeant Porter to the King.

References for the Battle of Lostwithiel:

Lostwithiel 1644 The Campaign and the Battles by Stephen Ede-Borrett

The English Civil War by Peter Young and Richard Holmes

History of the Great Rebellion by Clarendon

Cromwell’s Army by CH Firth

British Battles by Grant Volume I

The previous battle in the English Civil War is the Battle of Marston Moor

The next battle in the English Civil War is the Second Battle of Newbury

To the English Civil War index