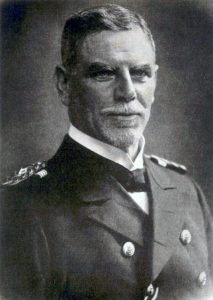

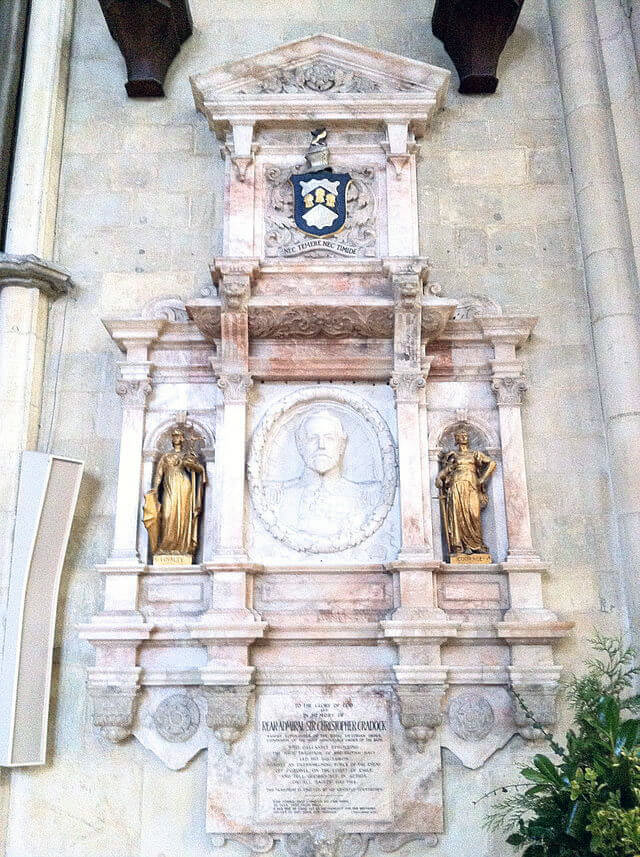

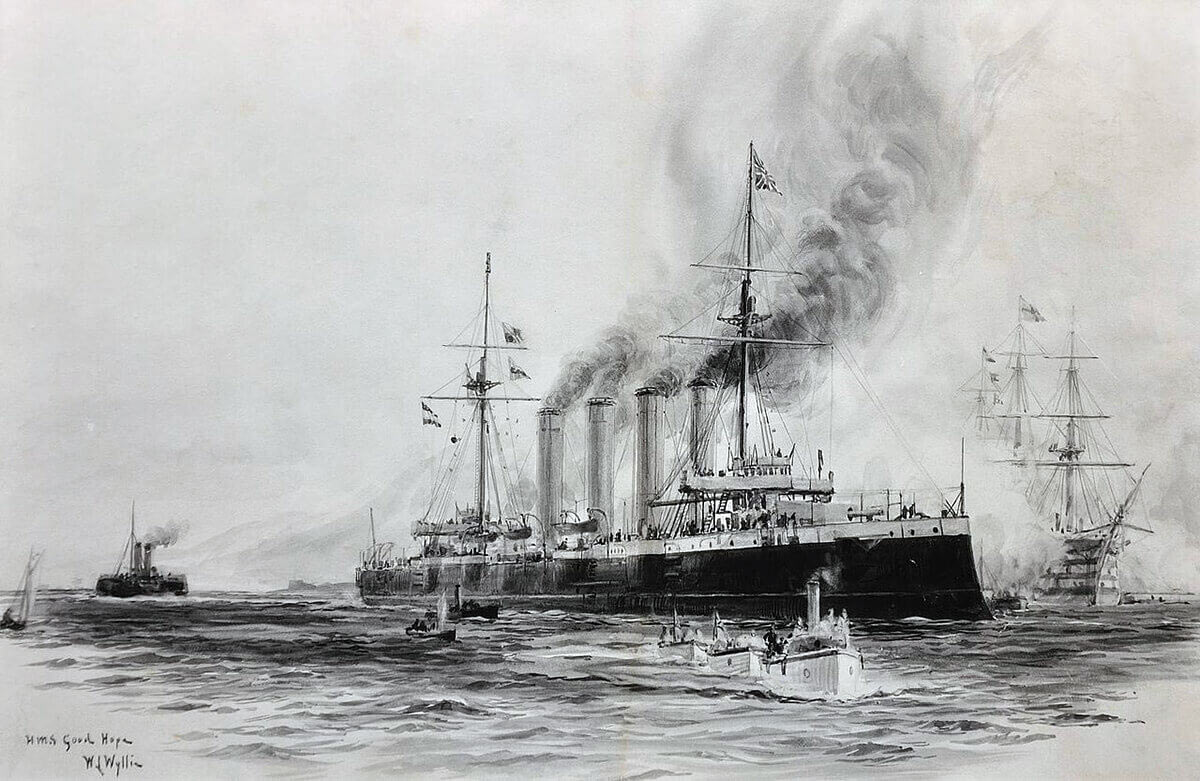

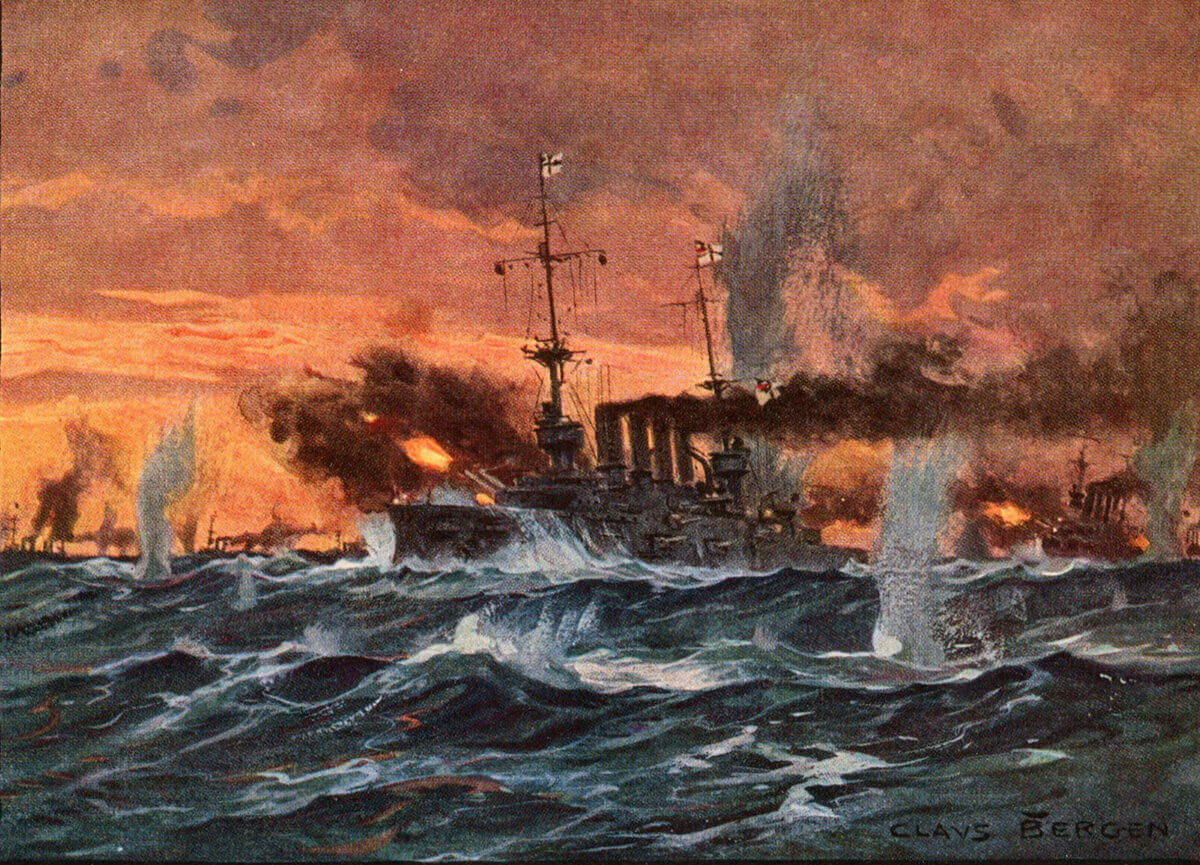

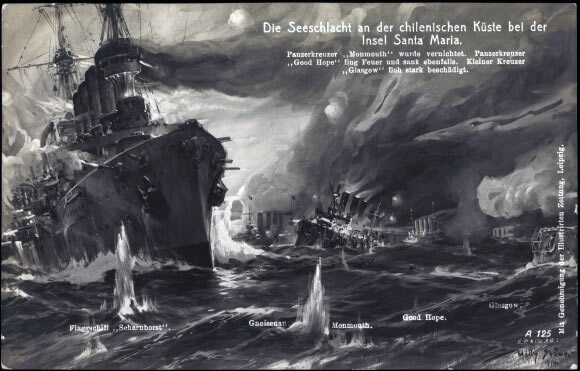

The first major naval battle of the First World War, fought on 1st November 1914: shocking Britain with the loss of her ships to Admiral Graf Spee’s Pacific Squadron and the death of Admiral Sir Christopher Cradock

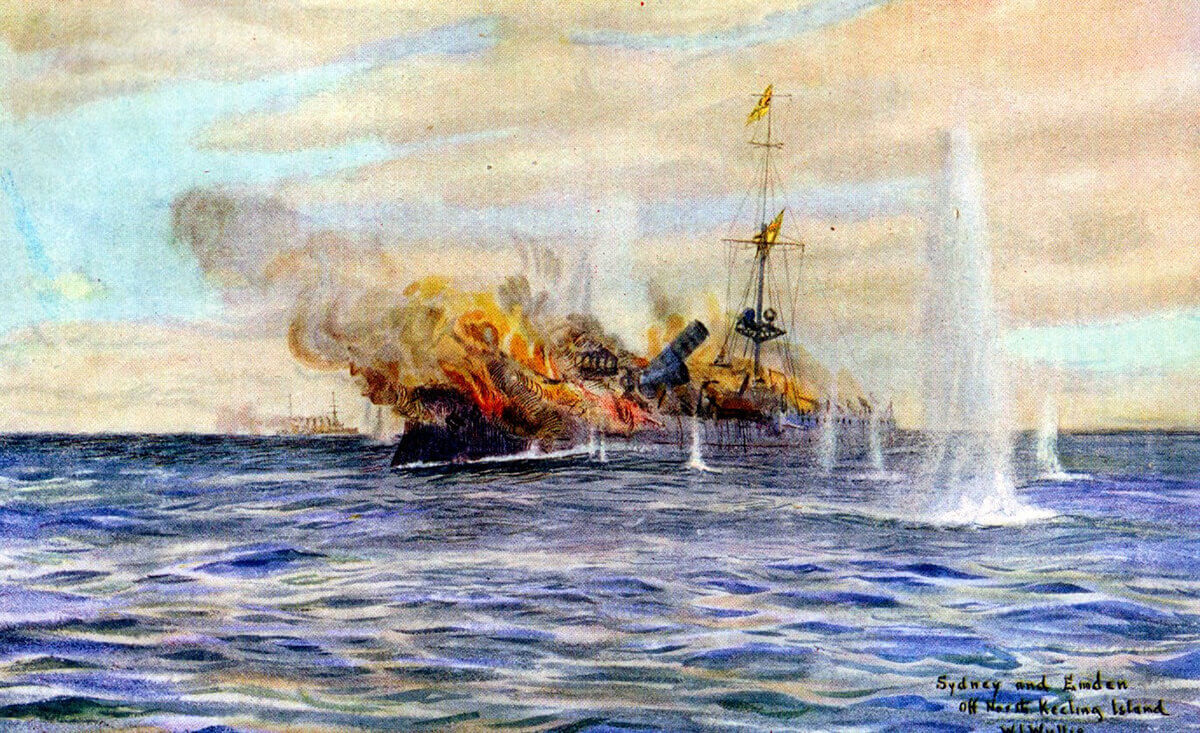

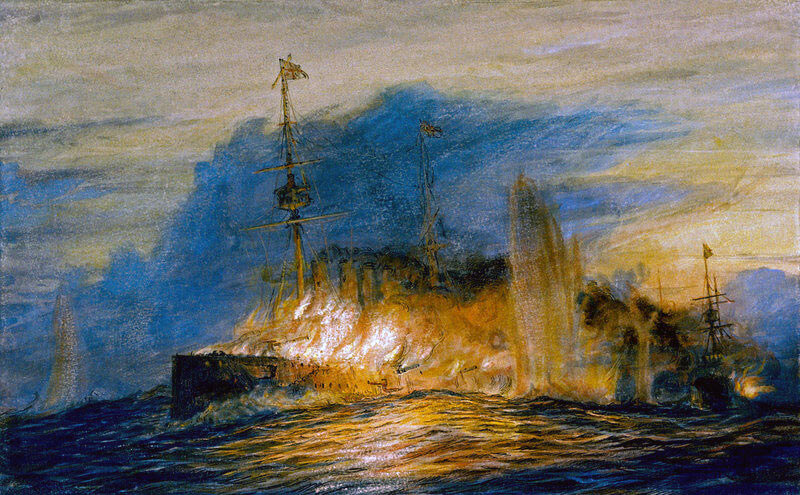

HMS Good Hope on fire towards the end of the Battle of Coronel, 1st November 1914 in the First World: picture by Lionel Wyllie

The previous battle in the First World War is the Texel Action

The next battle in the First World War is the Battle of the Falkland Islands

Two doomed Admirals; Cradock and von Spee:

————————————————

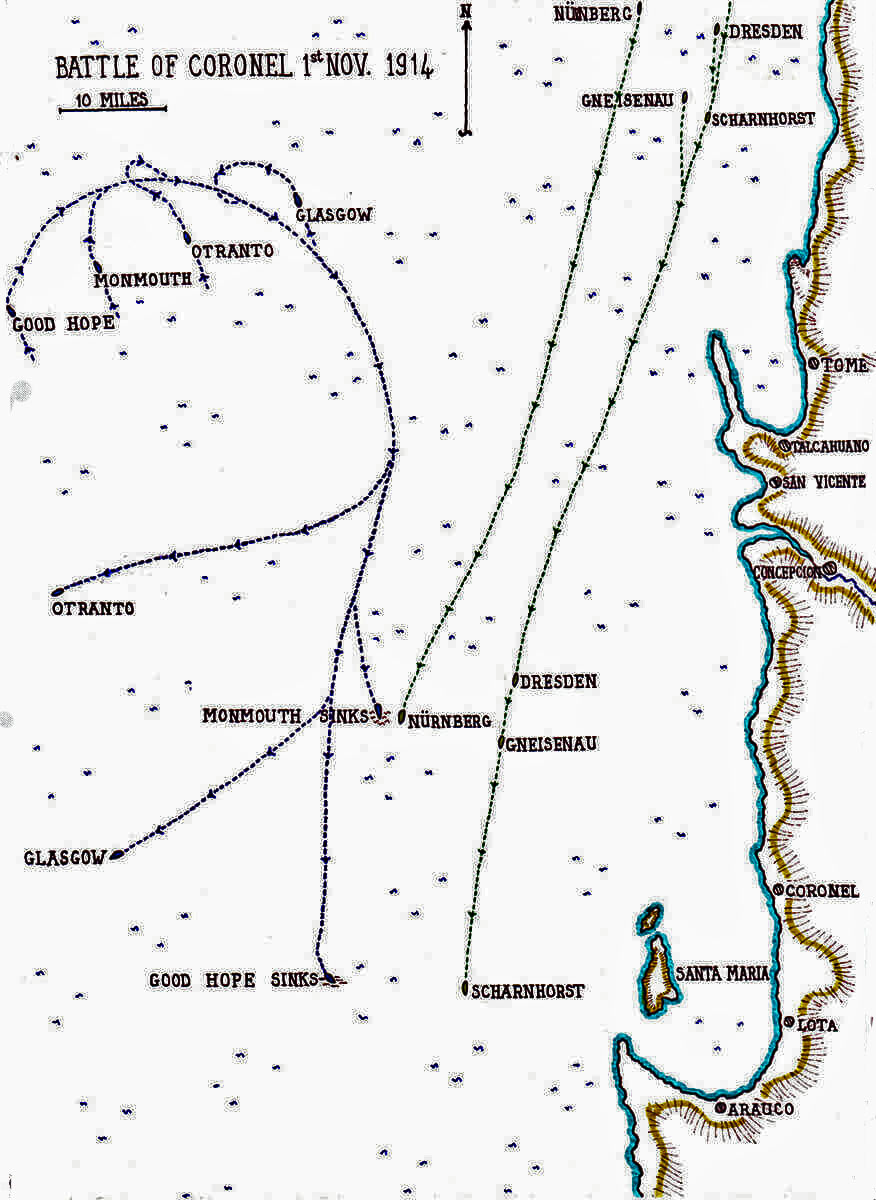

Battle: Coronel

Date of the Battle of Coronel: 1st November 1914

Place of the Battle of Coronel: Off the coast of Chile in the Pacific Ocean.

War: The First World War known also as ‘The Great War’.

Contestants at the Battle of Coronel: A British Royal Navy squadron against an Imperial German Naval squadron.

Ships involved in the Battle of Coronel:

The Royal Navy:

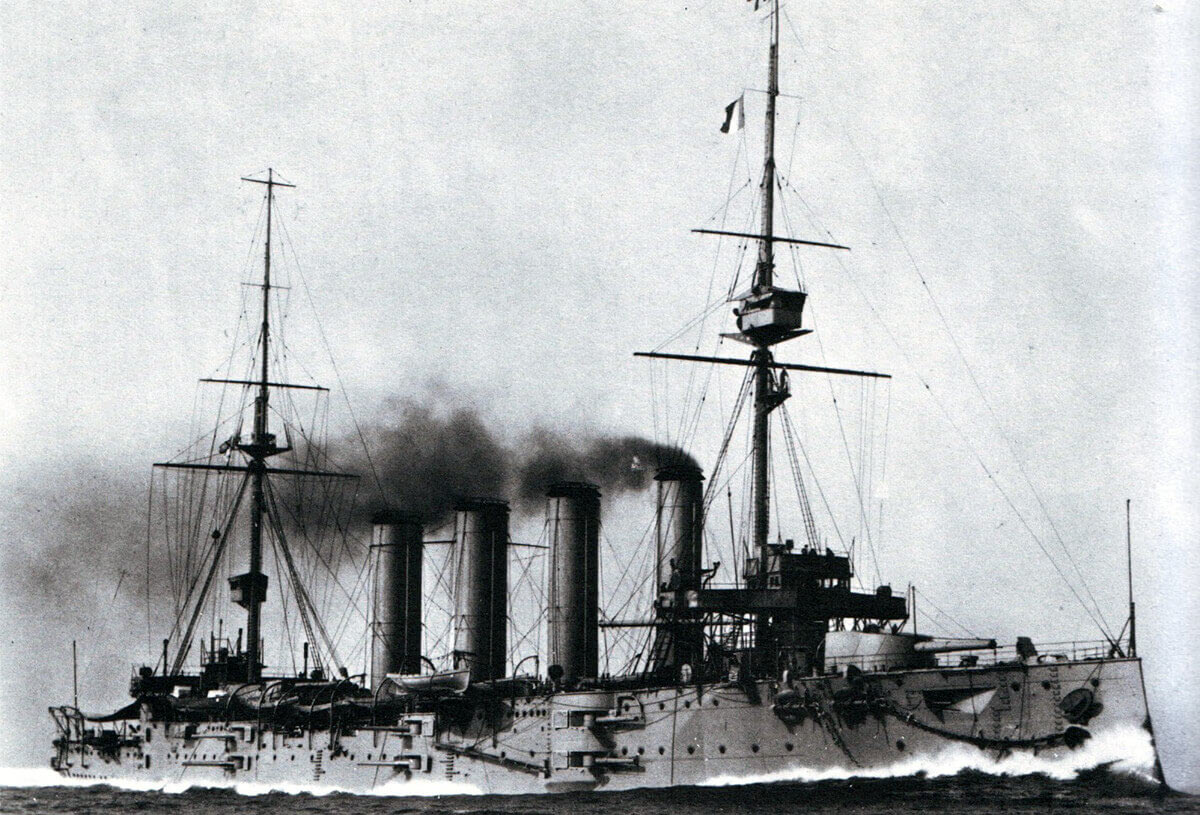

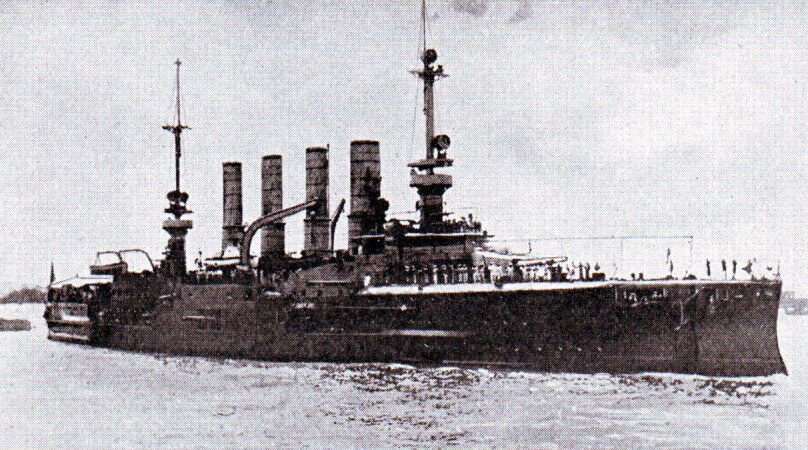

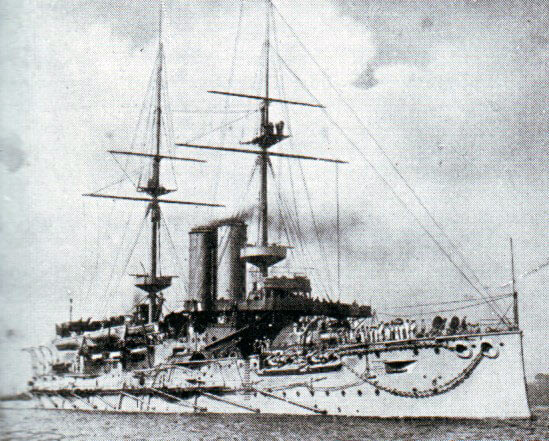

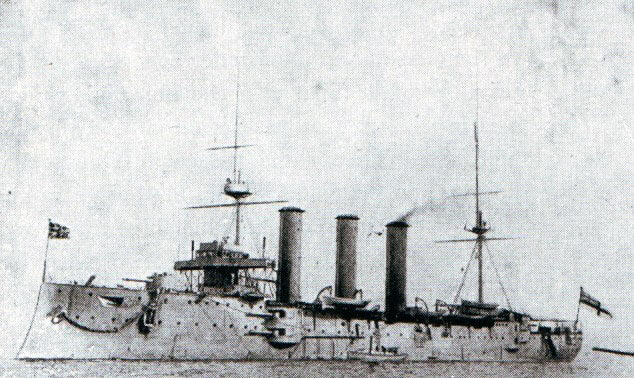

HMS Good Hope: Armoured (Heavy) Cruiser-completed in 1902-14,100 tons-main armament 2 X 9.2 inch and 16 X 6 inch guns-maximum speed 24 knots.

Flagship of Rear Admiral Sir Christopher Cradock the armoured cruiser HMS Good Hope: Battle of Coronel on 1st November 1914 in the First World War

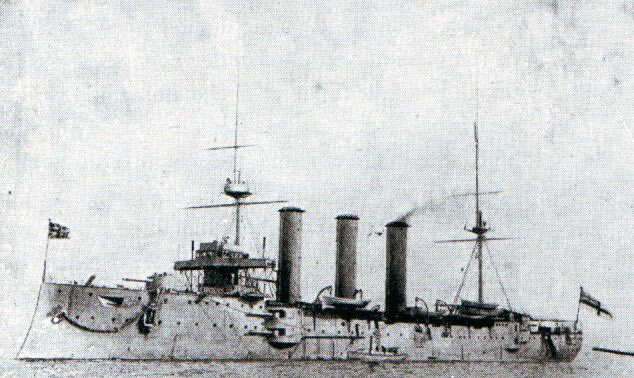

HMS Monmouth: Armoured (Heavy) Cruiser-completed in 1903-9,800 tons-main armament 14 X 6 inch guns-maximum speed 24 knots.

Rear Admiral Sir Christopher Cradock’s second armoured cruiser HMS Monmouth: Battle of Coronel on 1st November 1914 in the First World War

The Times History of the Great War states of these two ships: ‘The Good Hope represented one of the worst and most expensive types of ship ever built for the Navy in modern times. She was an immense target and much under-gunned for her displacement. The Monmouth, also of nearly 10,000 tons, carried no gun larger than a 6 inch.’

Both these ships mounted 6 inch guns in casemates on the sides of the ship. The lower guns could only be used in calm waters and probably were not brought into action at Coronel.

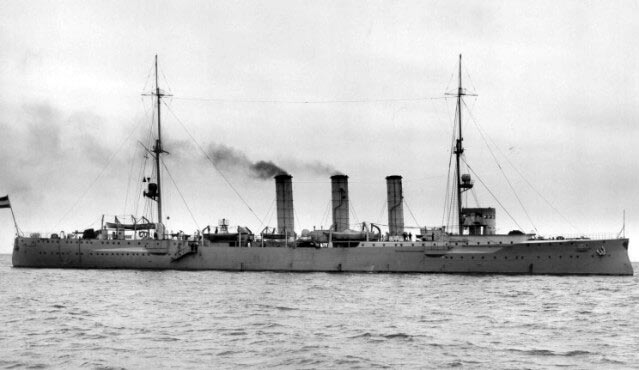

HMS Glasgow: Light Cruiser-completed in 1911-4,800 tons-main armament 2 X 6 inch and 10 X 4 inch guns-maximum speed 25 knots.

HMS Otranto: auxiliary cruiser (ex-civilian liner)-12,100 tons- main armament 6 X 4.6 inch guns: maximum speed 18 knots.

HMS Canopus: obsolete worn out Battleship-completed in 1897-12,950 tons-main armament 4 X 12 inch and 12 X 6 inch guns-maximum speed 16.5 knots. Canopus was 250 miles from the action and took no part, although a ship of Cradock’s squadron.

German Imperial Naval Ships:

Admiral Graf von Spee’s German East Asiatic Squadron at Tsing Tao: Battle of Coronel on 1st November 1914 in the First World War

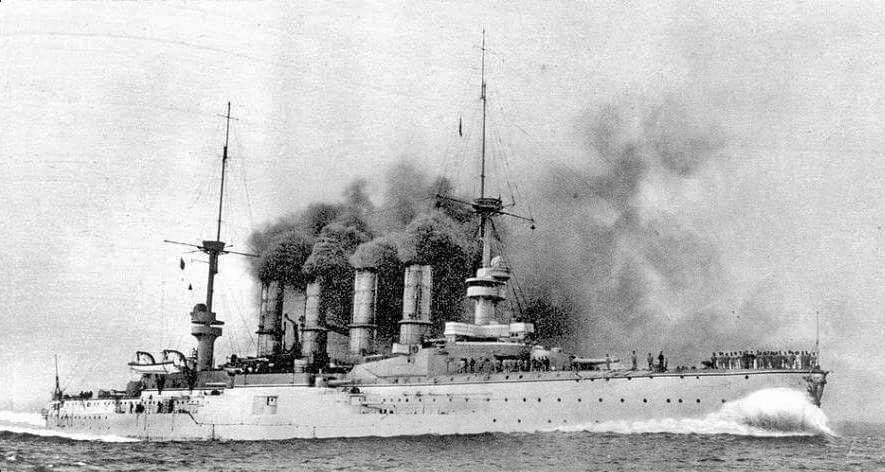

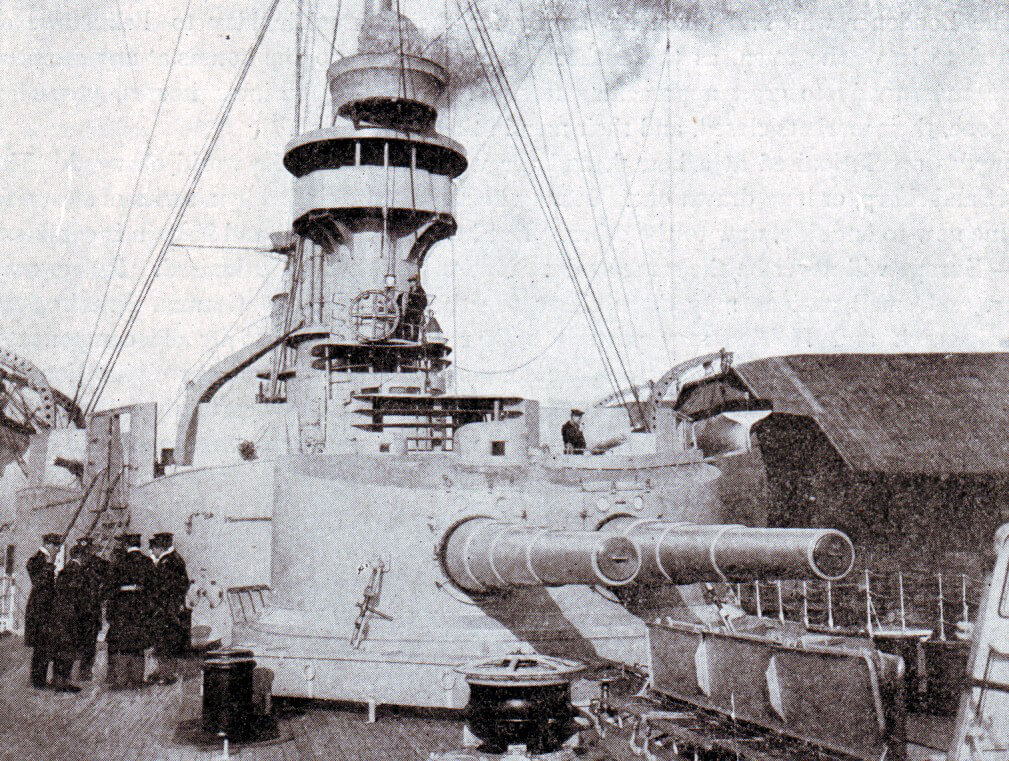

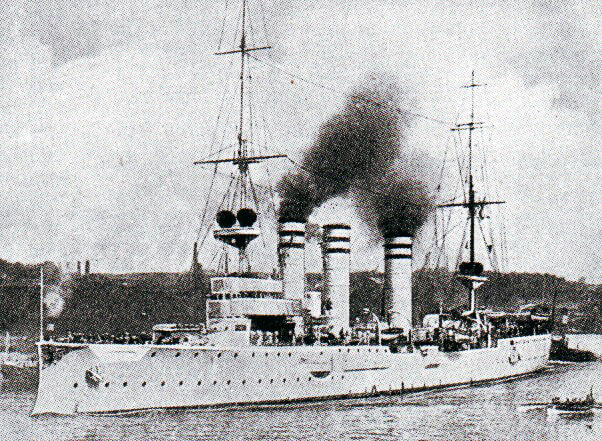

SMS Scharnhorst: Armoured (Heavy) Cruiser-completed in 1907-11,600 tons-main armament 8 X 8.2 inch and 6 X 6 inch guns-maximum speed 21 knots.

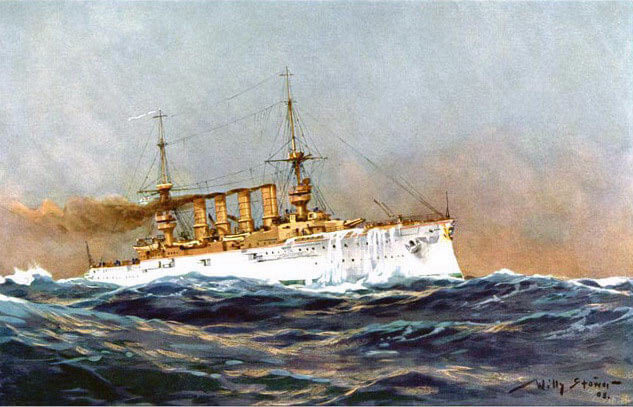

Admiral Graf von Spee’s flagship the protected cruiser SMS Scharnhorst at sea: Battle of Coronel on 1st November 1914 in the First World War

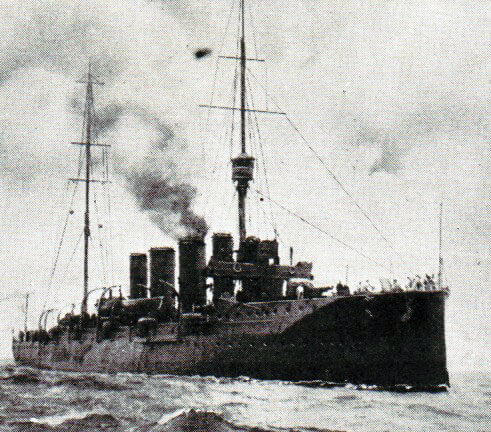

SMS Gneisenau: Armoured (Heavy) Cruiser-completed in 1907-11,600 tons-main armament 8 X 8.2 inch and 6 X 6 inch guns-maximum speed 24.8 knots.

SMS Leipzig: Light Cruiser-completed in 1906-3,250 tons-main armament 10 X 4.1 inch guns-maximum speed 24 knots.

SMS Dresden: Light Cruiser-completed in 1909-3,600 tons-main armament 10 X 4.1 inch guns-maximum speed 24 knots.

Admiral Graf von Spee’s light cruiser SMS Dresden: Battle of Coronel on 1st November 1914 in the First World War

SMS Nürnberg: Light Cruiser-completed in 1908-3,600 tons-main armament 10 X 4.1 inch guns-maximum speed 22.5 knots.

All the above ships except Otranto carried smaller guns, machine guns and torpedo tubes.

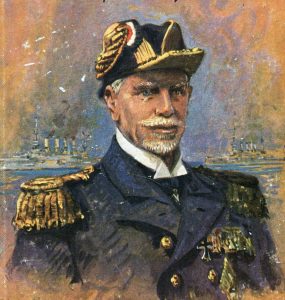

Admirals at the Battle of Coronel: The British Royal Navy Squadron was commanded by Rear Admiral Sir Percy Sir Christopher Cradock. The German squadron was commanded by Vice Admiral Reichsgraf Maximilian von Spee.

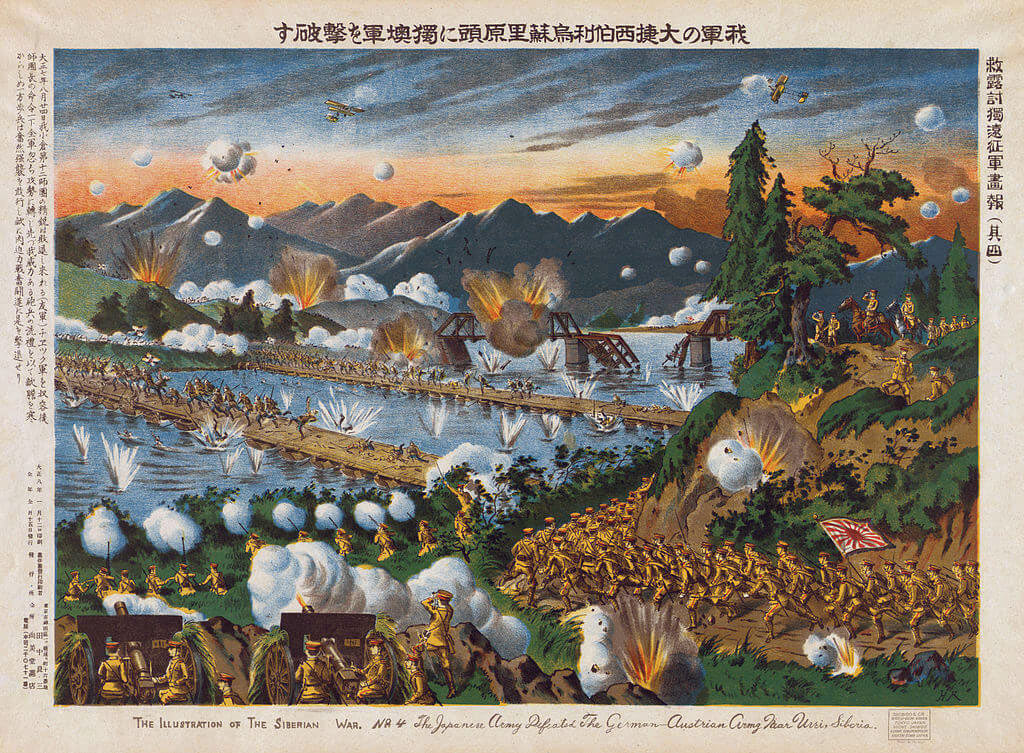

Japanese lithograph of the attack on Tsing Tao in 1914: Battle of Coronel on 1st November 1914 in the First World War

Winner of the Battle of Coronel: This was a resounding victory for the German Navy that caused jubilation in Germany and dismay in Britain. The German ships sank the Good Hope and the Monmouth. Glasgow, damaged, got away to take part in the Battle of the Falklands. Otranto got away. Canopus took no part in the battle, being too slow to keep up with the rest of Cradock’s squadron.

German naval officers at dinner in the wardroom: Battle of Coronel on 1st November 1914 in the First World War

Background to the Battle of Coronel:

At the outbreak of the First World War the main German High Seas Fleet was quickly blockaded into the complex of naval bases along the short German North Sea shore and into the Baltic by the British Grand Fleet and the Royal Navy ships stationed on the east coast of Britain. Only by way of powerful forays could the German navy break this blockade.

Germany maintained a significant presence in the Pacific Ocean, possessing German New Guinea, the Bismarck Archipelago and islands in the Solomons, Caroline, Ladrone, Pellew, Marshall Groups of Islands and in Samoa.

Of particular importance was the German presence in North-Eastern China. The German Navy maintained a naval base at Tsing Tao (now Qingdao), the home of the German Navy’s East Asiatic Squadron. The colony was administered by the Imperial German Navy not the German colonial authorities, the governor in August 1914 on the outbreak of war being Admiral Meyer Waldeck.

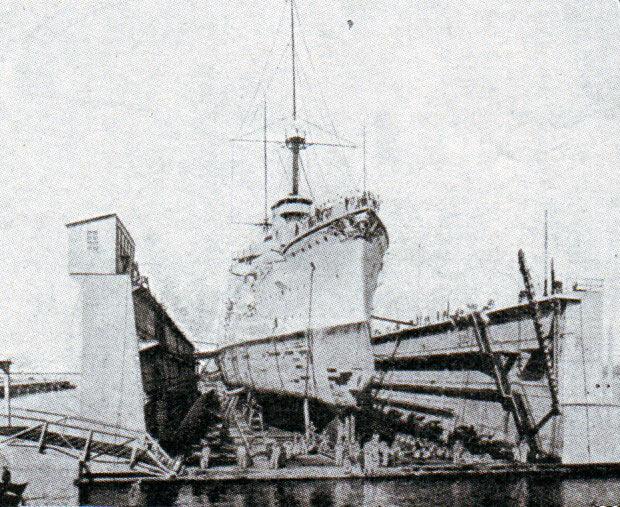

Dry dock in the German naval base of Tsing Tao in North-East China: Battle of Coronel on 1st November 1914 in the First World War

Japan, on her entry into the First World War on the side of the Britain, France and Russia, immediately launched a naval and army assault on Tsing Tao with the assistance of British troops and ships. The attack began on 31st October 1914.

The German East Asiatic Squadron was commanded by Vice Admiral Reichsgraf Maximilian von Spee. The two largest ships in the squadron were Armoured or Protected Cruisers (Panzerkruiser), SMS Scharnhorst and Gneisenau. His light cruisers were SMS Emden, Nürnberg and Leipzig.

Before the War Scharnhorst won the Kaiser’s gold medal for big ship shooting, while the Gneisenau won the Kaiser Prize for the Cruiser (China) Squadron in 1913.

The German radio station at Tsing Tao damaged by Japanese naval gunfire: Battle of Coronel on 1st November 1914 in the First World War

All the ships in Spee’s squadron were well drilled experienced ships with modern guns, commanded by determined and resourceful officers.

At the end of June 1914 Spee left Tsing Tao with Scharnhorst and Gneisenau, heading for Samoa, far to the east-north-east of New Zealand. Spee reached Ponape in the Caroline Islands on 17th July 1914, where he was joined by the light cruiser Nürnberg from the North American coast on 6th August 1914. On that day Spee’s squadron sailed north-west to complete his mobilisation for war on the remote Pagan Island in the Mariana Islands. Spee’s supply ships were to leave Tsing Tau and meet his squadron at Pagan Island. Spee also summoned the Emden to this rendezvous.

On the declaration of war on 3rd August 1914 the Royal Navy did not know where Spee’s squadron was. A major difficulty for the British, Australian and New Zealand authorities was the number of German civilian vessels that were known to be ready for conversion into naval surface raiders on the outbreak of war and that were in the area of the Indian and Pacific Oceans.

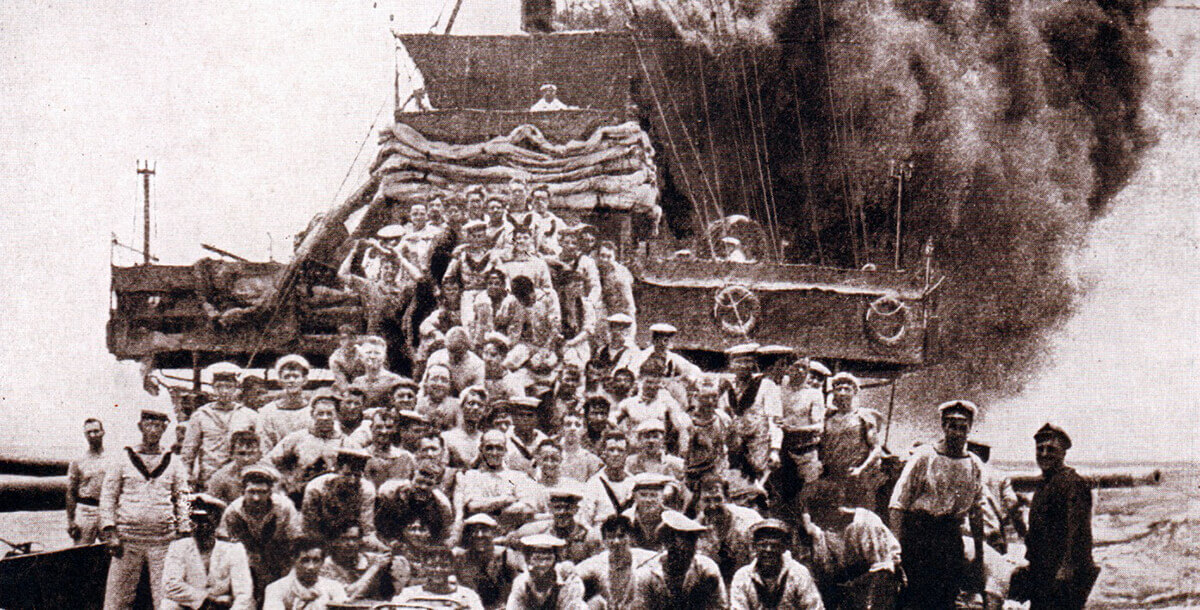

Landing party from SMS Emden after destroying the Australian Radio station on the Cocos Islands, immediately before Emden was intercepted and destroyed by HMAS Sydney on 9th November 1914

In the years leading up to war the German authorities identified large numbers of civilian liners and cargo vessels for immediate conversion into surface raiders in the event of war. The plan required these ships to meet supply ships anywhere in the world to be equipped with guns and ammunition.

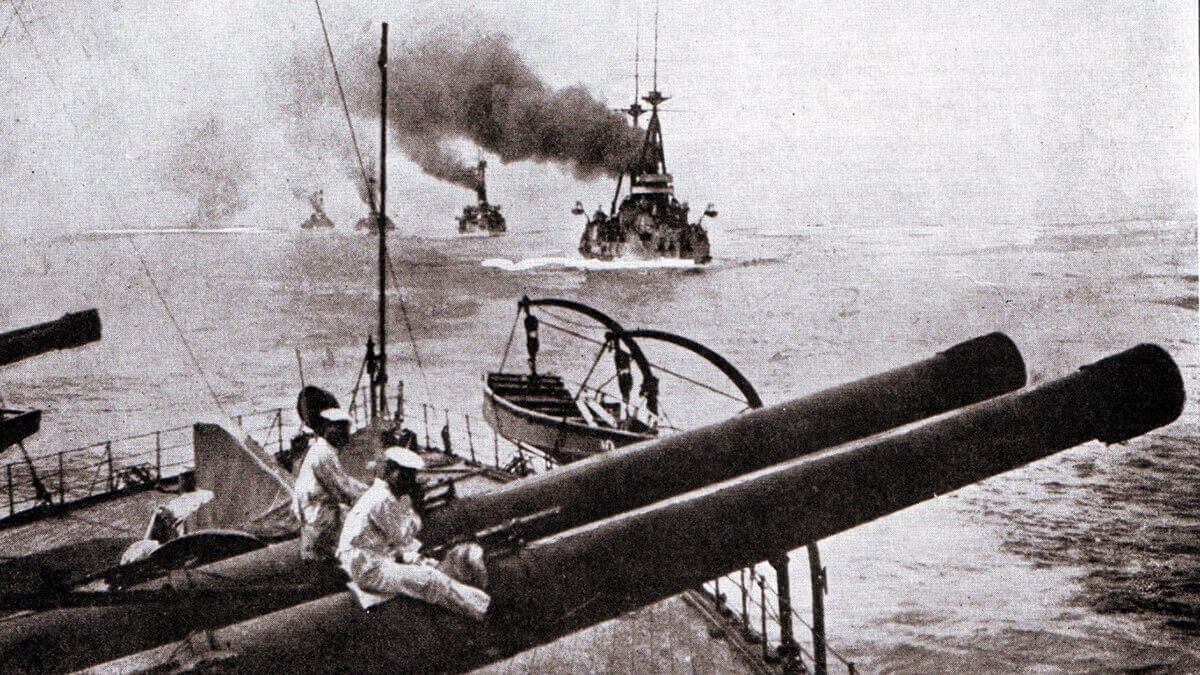

A major war role of Spee’s light cruisers was to act as commerce raiders. Of these the most notorious turned out to be the Emden in the Pacific. Other such cruisers were Königsberg off the East African coast and the Karlsruhe in the Atlantic.

The Royal Navy deployed a substantial number of ships in the area of the Indian and Pacific Oceans. The Navy’s main commitments were to protect the diverse British commercial sea traffic and in particular the transport of Indian, Australian and New Zealand troops to Europe and the Middle East. Another important commitment was to protect the web of radio stations across the area and the ocean bed telegraph cables where they landed.

Tracking down and destroying the individual German commerce raiders and cruisers in the vast area of the Indian and Pacific Oceans was enough of a problem. The presence somewhere at sea of Spee’s powerful squadron was altogether of a different magnitude.

Corbett in his history of naval operations points out the effect of Spee’s squadron in influencing British naval deployments all over the world.

Up to the Japanese entry into the War on the side of Britain, France and Russia, Admiral Jerram, the British naval commander on the China Station based at Wei-hei-Wei, was concerned to neutralise the importance of the German base at Tsing Tau. Following their declaration of war the Japanese immediately dispatched two powerful naval forces to attack Tsing Tau and Jerram was enabled to concentrate on finding and destroying Spee’s squadron and eliminating the network of German radio stations across the Pacific.

An area of concern remained the west coast of America, where the German light cruisers Leipzig and Nürnberg were known to be. Although the Nürnberg left to join Spee, this was not known and it was assumed that both German cruisers were in American waters.

Admiral Patey, commanding the Australian and New Zealand squadron, on 9th August 1914 attacked German New Guinea in the expectation of finding Spee with the Scharnhorst and Gneisenau, but no ship was found. The next target for the New Zealand and Australian squadron was Nauru and then the German sections of Samoa. It was Patey’s justified belief that Spee was heading for the American coast.

On 12th August 1914 the German light cruiser SMS Emden joined Spee at Pagan Island with her attendant auxiliary ships. Spee immediately dispatched Emden to the south. At the same time Spee decided to move his squadron to American waters. Tsing Tau, under threat of siege by the British and, as and when they joined the war, the Japanese, was no longer a feasible base and he could expect more favourable treatment from South American countries, particularly from Chile and Brazil, and could join up with the light cruiser SMS Leipzig. It would also be easier for him to break for Germany from that area.

Spee seems to have been particularly concerned to avoid the Battle Cruiser HMAS Australia (Invincible type), Admiral Patey’s flagship, which outgunned Spee’s whole squadron, having 8 X 12 inch guns and a maximum speed of 25 knots.

On 13th August 1914 Spee’s squadron heard radio messages from HMAS Australia of a strength to suggest she was not far off. On that day Spee sailed for the Marshall Islands, his next coaling stop on his route east.

On 15th August 1914 Japan presented Germany with an ultimatum demanding the surrender of Tsing Tau. The British began a blockade of Tsing Tao on 20th August 1914. On 27th August 1914, following the rejection of Japan’s ultimatum by Germany, two Japanese task forces began a blockade of Tsing Tao, releasing the British ships from that role. In addition the Japanese put two ships under British command.

On 20th August Spee sailed with his squadron in an easterly direction.

Admiral Jerram’s intention was that dealing with Spee’s squadron should be a priority for all British and Empire naval resources in the Indian and Pacific Ocean. Admiral Patey agreed, but the demands on naval resources made this difficult. The German light cruiser Königsberg, a fast modern ship, was based in Dar es Salaam and had to be covered. A large convoy was about to take Australian and New Zealand troops to the Middle East and Europe. Civil shipping all over the area had to be covered.

Jerram’s estimate was that Spee would move his squadron to Java preparatory to raiding into the Indian Ocean. He was partly right in that this was where the German cruiser Emden headed, but the rest of Spee’s powerful squadron continued on its route to the American coast.

By the beginning of October 1914 Admiral Patey secured German New Guinea and the Bismarck Archipelago to its north and was sailing north to intercept Spee, if he should attempt to enter the Indian Ocean.

Doubts on the whereabouts of the various German ships delayed the convoy of ANZAC troops to Europe. Two Japanese cruiser squadrons joined the search for the German ships.

Then on 2nd October 1914 news came in that Spee’s squadron had bombarded Tahiti. This confirmed that Spee was heading for America and not the Indian Ocean, changing the strategic situation in the region.

By this time the powerful Japanese Second Squadron, comprising the Battleship Satsuma and light cruisers Yahagi and Hirado, was heading for Rabaul.

On 4th October 1914 a radio message from Scharnhorst was intercepted (the code was known by the British) stating ‘Scharnhorst on the way between the Marquesas and Easter Island.’ A further message in clear warned of British and Japanese ships moving east. It was now certain that Spee was heading for America, where the German light cruiser Leipzig was believed already to be operating.

Admiral Graf von Spee’s second protected cruiser SMS Gneisenau: Battle of Coronel on 1st November 1914 in the First World War

Sufficient ships were available to protect British and Canadian interests off the coast of British Columbia: Captain Powlett with light cruisers HMS Newcastle (1908, 2 X 6 inch guns 26 knots) and HMCS Rainbow (1891, 2 X 6 inch guns 19.5 knots) and the Japanese ships; heavy cruiser Idzumo (1899, 4 X 8 inch, 22 knots) and the battleship Hizen (1900 ex-Russian, 4 X 12 inch guns, 18 knots).

On 1st October 1914 crews from two British ships taken by the Leipzig reached the American main land and confirmed that the German cruiser was operating off the South American coast. The conclusion of the British naval authorities in the Pacific was that Spee was heading for the same area to join up with the Leipzig. This would bring the German squadron into the area of Admiral Cradock’s command.

Rear-Admiral Sir Christopher Cradock on the outbreak of war commanded the 4th Cruiser Squadron in the West Indies (HMS Suffolk [flag], Lancaster, Essex and Berwick; all 9,800 tons, 8 to 14 X 6 inch guns, 23 knots).

Cradock’s main concerns were the German light cruisers Dresden and Karlsruhe, both known to be in the West Indies, and the 14 German liners in New York and other American harbours capable of being transformed into powerful auxiliary naval cruisers.

Cradock received his ‘War Telegram’ ordering mobilisation of the Royal Navy on 4th August 1914.

Admiral Sir Christopher Cradock’s flagship the armoured cruiser HMS Good Hope: Battle of Coronel on 1st November 1914 in the First World War: picture by Lionel Wyllie in 1901

On 12th August 1914 Cradock sailed to Halifax in Nova Scotia where he was joined by HMS Good Hope. Cradock moved his flag into Good Hope and on 16th August 1914 sailed to the southern ocean, leaving Suffolk, Essex, Lancaster, Carmania and the battleship Glory to deal with the northern commerce routes. His move coincided with the formal opening of the Panama Canal.

Captain Frank Brandt RN, captain of HMS Monmouth: Battle of Coronel on 1st November 1914 in the First World War

The eastern coast of South America was the concern of Captain Luce in HMS Glasgow. On 13th August 1914 HMS Monmouth arrived in Las Palmas on the Argentine coast and was ordered by the commander there, Admiral Stoddart, to join Luce’s command.

Dresden was now thought to be operating from a secret base on the eastern coast of Brazil. Dresden had been under orders to return to Germany on the outbreak of war. The British blockade made this impracticable and she was directed to join Spee in the Pacific instead.

On 4th September 1914 Admiral Phipps Hornby took over Cradock’s original command.

Dresden continued south down the coast of Brazil while Luce searched for her further north with Glasgow, Monmouth and Otranto.

Rear Admiral Sir Christopher Cradock’s armed merchant cruiser HMS Otranto: Battle of Coronel on 1st November 1914 in the First World War

It was believed by the British naval authorities in the South Atlantic from intercepted radio traffic and other observations that a concentration of German cruisers from the Pacific and the Atlantic in the Straits of Magellan, at the southern tip of South America, was imminent, with a possible attack on the Falkland Islands.

Cradock was confirmed in his decision to investigate and the Admiralty ordered HMS Canopus to join Cradock from the Cape Verde Islands, in order to give him a ship of force. Cradock moved south from Montevideo. By this time it was reported that the ships in the area of the Straits of Magellan were German coal transports and not naval vessels. It was feared that they were there to support Spee’s squadron on its imminent arrival off the South American coast. Cradock ordered the cruisers HMS Bristol and Cornwall to join him in the South Atlantic in anticipation of action with Spee’s squadron.

Intelligence gathering and communications in the area of the South Atlantic, South America and the Pacific were extremely difficult and unreliable. The German cruisers did their utmost to avoid detection and hid themselves away in remote coastal inlets and islands. When they moved they did so on constantly changing courses. Intelligence on the position of German cruisers came from ships in the area, crews from captured ships put ashore by the Germans and from coastal populations, much of which in South America was German sympathising, if not actually German. Often identification of German ships was out of date by the time it was received or just wrong. Radio communication was haphazard and easily jammed. Long range communication, i.e. to London, had to be conducted through telegraph from neutral South American countries. Many South American telegraph stations refused to accept messages in code.

On 14th September 1914 the Admiralty informed Cradock that the battleship HMS Defence was crossing the Atlantic to join him and ordered Cradock to search the Straits of Magellan and then return to cover the Falkland Islands. He was to ensure that he had the Canopus and at least one cruiser with his flagship HMS Good Hope until Defence arrived.

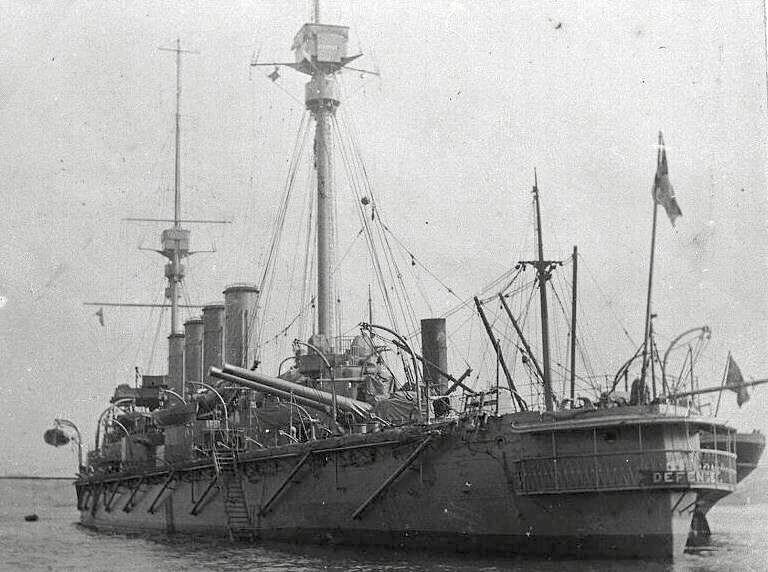

British Armoured Cruiser HMS Defence (sunk at Jutland in 1916): Battle of Coronel on 1st November 1914 in the First World War

Cradock received these instructions at Santa Catharina off the southern Brazilian coast where he found Captain Luce with HMS Glasgow, Monmouth and Otranto.

In the meantime the German cruiser Dresden was steaming south in the Atlantic to round the Horn into the Pacific and join Spee.

Cradock headed south leaving Bristol and Cornwall to continue the search for Dresden and Karlsruhe off the Atlantic Brazilian coast.

The next news was that Spee’s squadron had appeared in Samoa in the Pacific and headed north-west. This was a blind and Spee once out of sight of land turned back towards South America. The news was sufficient for Cradock’s instructions to be cancelled. Cradock was ordered to send two cruisers and an armed liner to attack German shipping off the South American coast.

On 25th September 1914 Cradock fell in with the SS Ortega, whose Captain Kinnier informed him that he had been fired on by a 3 funnelled cruiser off the Chilean coast, clearly the Dresden.

It was this information that decided Cradock to take his squadron into the Pacific. Further information reported that the German tender SS Seydlitz was putting to sea from Valparaiso, the Chilean capital on the west coast of South America, all indicators of a concentration of German war ships off the Chilean coast.

Account of the Battle of Coronel:

Cradock arrived at Punta Arenas, the Chilean port in the Straits of Magellan, to be informed by the British Consul that the Germans were using Orange Bay in Hoste Island near to Cape Horne as a base. Cradock carried out a covert raid on the bay but there were no German transports present.

After a return to the Falklands to coal and a resumption of station in the Straits of Magellan the information came in to Cradock with increasing urgency that Spee was heading for Easter Island off the Chilean coast. Cradock ordered Luce to take his division north to Valparaiso to reconnoitre and take in supplies, while he remained in Good Hope.

The Admiralty instructed Cradock to prepare to meet Scharnhorst and Gneisenau and possibly one Dresden class light cruiser. However communications were extremely uncertain, messages taking up to a week to pass between Cradock and London, due to atmospherics and local political constraints. It was apparent to Cradock that the Admiralty underestimated the strength of Spee’s squadron. Cradock was of the view that Spee would have three light cruisers, Leipzig, Nürnberg and now Dresden.

On hearing that Spee was in Samoa the Admiralty had ordered HMS Defence to the Dardanelles, but without informing Cradock that he was losing the ship.

German Armoured Cruiser SMS Scharnhorst Flagship of Admiral Graf von Spee at the Battles of Coronel and Falklands in 1914 in the First World War: picture by Willy Stoewer in 1905

On 8th October 1914 Cradock sent a telegram to London saying that there should be two forces sufficient to meet Spee, one in the Pacific and one in the South Atlantic. Cradock’s reasoning was that if Spee managed to pass the Horn unintercepted he might head for the West Indies, causing chaos to Allied trade or to the coast of Africa where he could interfere with Allied operations there. This message was not received until 12th October.

On 12th October in the light of Cradock’s message the Admiralty realised that Spee’s squadron was indeed heading for America and was now a major priority. Cradock’s plan was approved. He would act in the Pacific with Good Hope, Canopus, Monmouth, Glasgow and Otranto, while Admiral Stoddard operated in the River Plate area with Carnarvon, Cornwall, Bristol, two merchant cruisers and Defence, again ordered to the South Atlantic.

On 15th October Captain Luce in HMS Glasgow reported that Valparaiso was ‘full of German ships some of which have been out supplying cruisers’.

Rear Admiral Sir Christopher Cradock’s light cruiser HMS Glasgow: Battle of Coronel on 1st November 1914 in the First World War

Preparing to move north from the Straits of Magellan Cradock faced a considerable problem in HMS Canopus. The aged battleship was intended by the Admiralty to provide Cradock with the heavy guns needed to combat the two German armoured cruisers Scharnhorst and Gneisenau. Canopus arrived in the Falklands on 22nd October 1914, a week late, in a bad state and required three days of repairs. Even then she could only achieve around 14 knots, which was inadequate to keep up with the rest of Cradock’s squadron of which the slowest was Otranto with 18 knots, the rest of the ships being capable of around 24 knots.

Cradock warned the Admiralty that Canopus would reduce his squadron to an overall speed of 12 knots making it a matter of luck whether he brought Spee’s squadron to action.

Cradock appears to have considered the Admiralty’s instruction to him to ‘search and protect trade’ an order to fight Spee whatever the consequences.

On departing from Port Stanley, Cradock left a letter to be forwarded to his friend Admiral Hedworth Meux in the event of his death, stating that he did not intend to suffer the fate of Rear-Admiral Ernest Troubridge, who faced court-martial for failing to engage the German warships Goeben and Breslau in the Mediterranean in August 1914. The Governor of the Falklands and his aide both reported that Cradock did not expect to survive his squadron’s foray into the Pacific. In the event Troubridge was acquitted at his court martial, but was not again given a sea going appointment.

Spee arrived at Easter Island, a Chilean possession some 2,000 miles from the coast of South America. His squadron were there joined by Dresden and Leipzig. Spee sailed again on 18th October 1914 for Mas-a-fuera, the next island group on the route to Chile, where he met the colliers and supply ships from Valparaiso.

The day Cradock left the Falklands for the Pacific news came in that the German cruiser Karlsruhe had been located off the Brazilian coast and was not, as believed, in the Pacific with Spee.

On 26th October 1914 Cradock joined Captain Luce at the secret base on the Pacific side of the Straits of Magellan. It seems clear that Cradock considered he was under orders to intercept and attack Spee’s squadron. Cradock took the view that the Canopus was so slow that to have the ship in company with the rest of his squadron would make it impossible to intercept a squadron as fast as Spee’s. Cradock directed Canopus to escort the supply ships in the rear while he pressed ahead with his four cruisers.

Rear Admiral Sir Christopher Cradock’s aged battleship HMS Canopus: Battle of Coronel on 1st November 1914 in the First World War

The comparison with Troubridge’s situation is interesting. Troubridge declined to attack the Goeben and the Breslau because he had no guns of the range of Goeben’s 12 inch guns and his ships must therefore attack for a considerable period under fire from these guns before his own guns would be in range. The result must inevitably be the destruction of his squadron of cruisers.

Without Canopus’ 12 inch guns Cradock had no gun to compare with the armament of Scharnhorst and Gneisenau, while with Canopus his squadron would be too slow to catch the German squadron. Cradock appeared to know that in order to comply with his orders as he interpreted them he faced the destruction of his ships and probably his own death.

The Admiralty, now headed by Churchill and Fisher, sent a further message to Cradock informing him that he was not required to fight Spee’s squadron without Canopus. This message did not reach Cradock.

On 27th October Cradock sent Luce in Glasgow on to Coronel in the hope of receiving further instructions from the Admiralty via the telegraph station there, to relieve him of the fatal obligation to intercept Spee’s squadron.

On 28th October Cradock instructed Canopus with the supply ships to move north and join him. Otranto was dispatched to check Puerto Montt.

Rear Admiral Sir Christopher Cradock’s flagship the armoured cruiser HMS Good Hope: Battle of Coronel on 1st November 1914 in the First World War

In the area of Santa Maria Island, where he was looking for a German sailing ship, Luce intercepted a series of wireless messages between German ships. They were in code but indicated the imminence of Spee’s squadron. On receipt of this information Cradock decided to sail north with Good Hope and Monmouth at 6am on 30th October. In the meantime he was joined by Canopus and the accompanying supply ships.

On arrival Canopus was found to be in need of repairs which required her to go into an anchorage for 24 hours.

In view of the radio traffic Glasgow patrolled to the north and north-west of Santa Maria Island rather than enter Coronel. Early on 1st November both she and Otranto rejoined Cradock’s squadron. At 1am Glasgow heard Leipzig giving her call sign on the radio, apparently very close.

Cradock formed the view at this stage that Spee was heading north for the Galapagos Islands, off the coast of Ecuador, and the Panama Canal, while Leipzig was still in the south. It seems that Cradock was unaware that the Anglo-Japanese squadron was under orders to cover that area. Cradock considered it his duty to press on after Spee.

Cradock radioed Canopus ordering her to bring up her two colliers to St Felix, an island 500 miles to the north of the islands of St Juan Fernandez, presumably intending to refuel there.

Glasgow was sent into Coronel with telegrams to the Admiralty explaining Cradock’s intention to move north after coaling at St Juan Fernandez, and ordered to meet the rest of the squadron 50 miles west of Coronel at noon on 1st November 1914.

Further strong radio signals indicated the presence of Leipzig, causing Cradock to form a line of search moving north.

Sir Julian Corbett in his ‘Naval Operations Volume I’ speculates that Cradock assumed that as two weeks had passed since Spee was expected to arrive in the area he must have taken his squadron north to the Panama Canal and that any action against him would be by the Anglo-Japanese North Pacific Squadron with its Japanese battleship, and that he may have considered that he would be part of a powerful force dealing with the German ships. Corbett finds it hard to believe that Cradock would have deliberately brought an action that he knew he could not win and that was very likely to lead to the destruction of most of his ships. Yet this appears to be what Cradock believed would happen and that his orders did not permit him to avoid such a cataclysm.

Spee arrived at Easter Island on 12th October 1914 and there met up with SMS Dresden. On 18th October, after replenishing his supplies, Spee sailed for Mas-a-fuera, where he was joined by the German auxiliary cruiser Prinz Eitel Friedrich. On 27th October Spee sailed again and at midday on 30th October he was fifty miles off Valparaiso.

On 31st October Spee heard of the presence of HMS Glasgow in Coronel and sailed to catch her. He arrived after Glasgow had left for the rendezvous 50 miles to the west.

At this time Cradock was sailing north in the expectation of catching Leipzig, while Spee was sailing south hoping to surprise Glasgow. Neither force was aware of the presence of the other.

At around 2.30pm on 1st November 1914 Glasgow rejoined the squadron.

At 2.30pm Admiral Cradock formed his squadron to conduct a sweep to the north, looking for Leipzig, ordering his ships to take station 15 miles apart on a line north-north-west with his flag ship Good Hope on the outer flank and the other ships in the order Monmouth, Otranto and Glasgow, at a speed of 10 knots.

Admiral Graf von Spee’s light cruiser SMS Leipzig: Battle of Coronel on 1st November 1914 in the First World War

The wind was strong from the south-east and there was a heavy sea, conditions which precluded the use of the lower 6 inch gun casemates on the sides of Good Hope and Monmouth in any action.

At 4.20pm the British ships were still forming line when Glasgow saw smoke on her starboard bow. Glasgow turned east to investigate.

At 4.40pm Glasgow reported that the smoke was from the Scharnhorst, Gneisenau and a light cruiser. The German ships were sailing south with Scharnhorst, Gneisenau and Leipzig in the lead and Dresden and Nürnberg further behind, having been concerned in the pursuit of a small coaster.

The German squadron turned towards Glasgow, which turned away and steamed at full speed towards Good Hope, which was rushing towards her, followed by Monmouth and Otranto.

As the battle developed Canopus, the ship the Admiralty intended to give Cradock the fire power he needed to fight Spee on anything like equal terms was 300 miles to the south, toiling north with her colliers.

German records describe the wind as from the south strength 6 with a high sea running, the worst possible conditions for Good Hope and Monmouth’s lower 6 inch gun casemates.

At 5pm Glasgow saw Good Hope and 10 minutes later Cradock ordered his ships to concentrate on Glasgow, steaming at full speed, to be as near the German squadron as possible.

As they ran towards Good Hope the three British ships were on a course west-south-west. Spee turned his line to conform to this course, but turned back to south-west after 10 minutes.

At about 6pm Spee saw Good Hope, which by this time was in line ahead leading the other three British ships. The British and German squadrons were on broadly parallel courses about 15 miles apart heading in a generally southerly direction down the South American coast.

Memorial in the Canadian Royal Naval College to the four Canadian midshipmen killed on HMS Good Hope: Battle of Coronel on 1st November 1914 in the First World War

Spee was sailing at around 14 knots, with only some of his ships’ boilers fired. Spee ordered all boilers to be lit and for the rear ships to close up. He worked his speed up to 20 knots, heading south in order to avoid the British squadron working around to his eastern flank, possibly to enable it to escape into Chilean neutral waters.

Cradock’s intention seems to have been to cut across the bows of the German squadron. His course was south-east. Cradock soon found this manoeuvre impracticable in view of Otranto’s maximum speed of 15 knots and turned to south-south-east and then finally to south, accepting that the action must be fought in parallel with the German ships.

The German squadron was about 12 miles to the east of the British. At about 6pm the British ships all turned four points to port, in an attempt to bring themselves closer to the German line. The Germans responded by turning away in succession to keep the distance between the squadrons at 18,000 yards (10 miles). Both squadrons were now sailing approximately south on slightly converging courses, about 10 miles apart.

At 6.15pm Cradock ordered an increase in speed to 17 knots, directing Otranto to keep up as best she could, and turned one point towards the German line, expecting his ships to comply. Cradock radioed Canopus, informing her that he was about to attack the German squadron.

By now Dresden was on station at the rear of the German line. Cradock reduced speed to 16 knots and called up Otranto. In fact Otranto now overtook Glasgow and pulled over to her starboard.

Admiral Graf von Spee commander of the German East Asiatic Squadron at the Battle of Coronel 1st November 1914 in the First World War: picture by Claus Bergen

Conditions were bad. The sun was setting (sunset was at approximately 7pm). The wind was strong and blowing up squalls and rain. If Cradock could force an action before the sun set the advantage would be his as the German gunners would have the sun in their eyes. As soon as the sun set the situation would reverse. The German ships would be in darkness and the British ships in silhouette against the sunset glow.

Spee held off until the sun set. His line was still not properly formed, with excessive gaps between Gneisenau and Leipzig and Leipzig and Dresden. All the ships were rolling heavily.

At around 7.05pm at a range of 12,000 yards the German ships opened fire on the British squadron.

Corbett makes the comment: ‘Under such conditions of light, with heavy seas breaking over their engaged bows, what chance had our comparatively old ships, which had had no opportunity of doing their gunnery since they were commissioned for the war (with largely naval reserve crews in Good Hope and Monmouth), against the smartest shooting squadron in the German service, and that squadron superior in numbers, design, speed and gun power?’

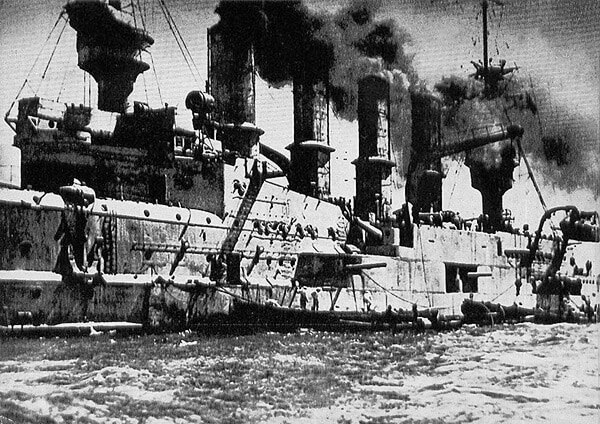

With her third salvo Scharnhorst put Good Hope’s forward big gun out of action, before it could be fired. Otranto observed a sheet of flame from Good Hope.

Gneisenau fired salvoes into Monmouth which was on fire within 3 minutes of the German armoured cruiser’s first shots. Leipzig and Dresden opened fire on Glasgow which fired back. Otranto quickly pulled out of the line, being too large and too under gunned to take part in the battle and watched from the west.

Rear Admiral Sir Christopher Cradock’s second armoured cruiser HMS Monmouth: Battle of Coronel on 1st November 1914 in the First World War

The British gunners were unable to respond to the German shellfire in the conditions. The German ships could not be seen in the dark and the bad weather conditions, while the British ships stood out against the sunset glow. Further fires broke out on Monmouth which was unable to keep her position.

Glasgow steered between Monmouth and Good Hope and opened fire on the Scharnhorst and the Gneisenau, hitting both and causing a fire on Scharnhorst. Leipzig and Dresden continued to fire on Glasgow. Although for some time untouched Glasgow finally received a hit on her waterline from a German light cruiser, making a 6 foot square hole. She continued to fight on.

For the two British armoured cruisers the end was approaching. The range was down to 5,500 yards and Good Hope was being hit by salvo after salvo from the invisible Scharnhorst. She had been on fire since the beginning of the action and a further major fire broke out in the bridge area. Good Hope was still firing but had lost her station, veering towards the German cruiser.

Main forward gun turret on SMS Scharnhorst mounting two 8.2 inch guns: Battle of Coronel on 1st November 1914 in the First World War

It was dark with the moon hidden by clouds and rain squawls. Suddenly there was an immense explosion on Good Hope, a sheet of flame rose to 200 feet, and she ceased firing.

Scharnhorst now joined Gneisenau in firing on Monmouth. The British ship turned away to the west and managed to extinguish the fires on board so that she could no longer be seen. Glasgow followed her, firing at the German ships. Every time Glasgow fired the whole German line returned her fire.

SMS Scharnhorst at the Battle of Coronel on 1st November 1914 in the First World War: picture by Claus Bergen

As Glasgow followed Monmouth she found that the armoured cruiser had turned north, to present her stern to the following sea, being badly down at the bows and making water forward.

The moon was now up, although largely obscured by the clouds and squalls, and the German squadron closed in on the two British ships. Spee ordered his light cruisers to make a torpedo attack when the circumstances were right.

Glasgow could do nothing further to assist Monmouth and turned away to the west to escape. An unarmoured ship, Glasgow estimated that 600 rounds were fired at her. She had suffered five hits on the waterline but the full load of coal she carried cushioned the impact. She had not been on fire. Glasgow made off to the west at full speed followed by Otranto, escaping into the dark.

Spee endeavoured to take his squadron around the British ships to put them against the moon, thereby missing Glasgow and Otranto.

A German postcard celebrating the victory of Coronel, called the Battle of the Island of Santa Maria: Battle of Coronel on 1st November 1914 in the First World War

After extinguishing the fires caused by Gneisenau’s initial salvos, Monmouth managed to disappear into the dark, heading north. Unfortunately Nürnberg passed close by her while coming up to take station at the rear of the German line and saw the British cruiser. Nürnberg opened fire. Monmouth was listing heavily to port so that her guns were unusable.

Admiral Graf von Spee’s light cruiser SMS Nürnberg: Battle of Coronel on 1st November 1914 in the First World War

After a period of firing Nürnberg ceased firing to give Monmouth the opportunity to haul down her colours and surrender, pointedly shining her searchlight on the British Ensign. Monmouth did not do so. Nürnberg resumed firing at point blank range and Monmouth capsized and sank.

HMS Monmouth sinking under fire from SMS Nürnberg: Battle of Coronel on 1st November 1914 in the First World War: picture by Lionel Wyllie

The German ships then searched for Good Hope, which had sunk. Everybody in the crews of the two British armoured cruisers, Good Hope and Monmouth, was lost.

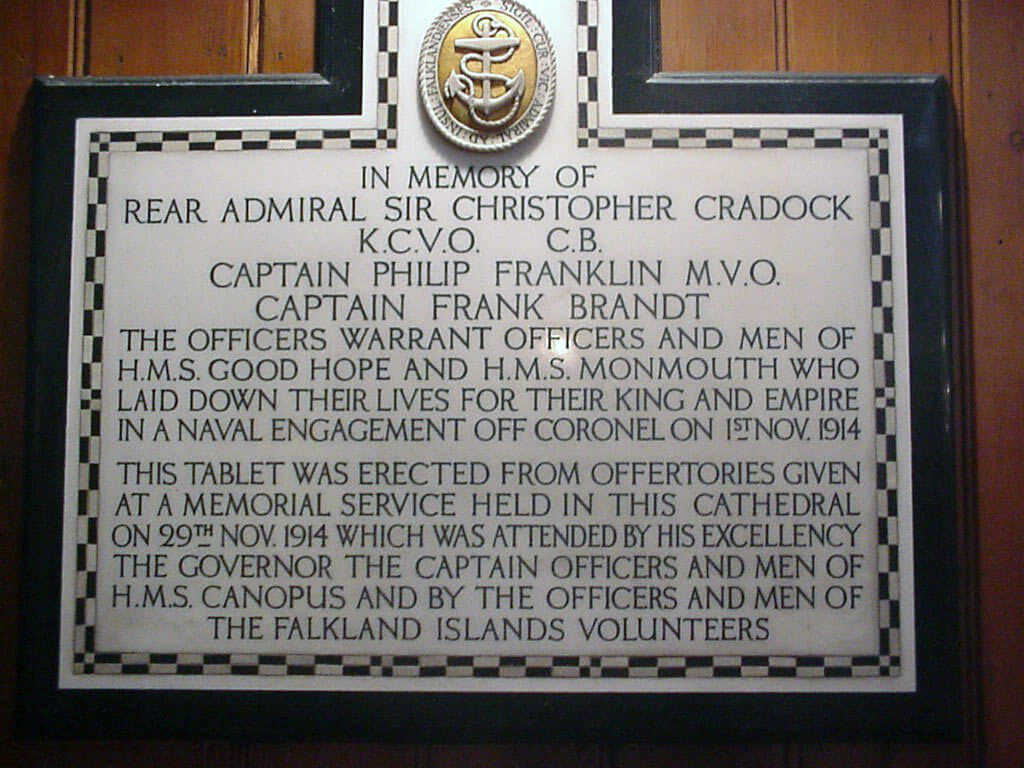

Casualties at the Battle of Coronel:

British Squadron:

HMS Good Hope: Admiral Sir Christopher Cradock and 919 officers and men, the whole crew, lost.

HMS Monmouth: 735 officers and men, the whole crew, lost.

HMS Glasgow: 5 wounded.

Memorial in Stanley Cathedral to the crews of HMS Good Hope and Monmouth: Battle of Coronel on 1st November 1914 in the First World War

HMS Otranto: no casualties.

German squadron:

SMS Scharnhorst inflicted around 40 hits on Good Hope, firing 422 8.2 inch shells, leaving 350. She suffered no casualties.

SMS Gneisenau suffered 3 wounded. She fired 244 8.2 inch shells leaving 528.

The other German ships suffered no casualties.

Aftermath to the Battle of Coronel:

Following the battle Spee was aware, possibly through Glasgow’s radio messages, that there was a battleship in the rear of Cradock’s squadron. He believed it to be a ‘Formidable’ class ship and did not feel able to take the risk of following up his success by continuing south. Spee took the Scharnhorst, Gneisenau and Nürnberg north to Valparaiso, leaving Leipzig and Dresden to search for the Glasgow and Otranto.

Admiral Graf von Spee’s squadron off Valparaiso; Scharnhorst and Gneisenau at the back left, with Nürnberg to their right: Battle of Coronel on 1st November 1914 in the First World War

Admiral Graf von Spee in Valparaiso after the Battle of Coronel on 1st November 1914 in the First World War

Having spent the permitted twenty-four hours in port Spee took his ships to his island base of Mas-a-fuera to await the return of the two light cruisers.

The surviving British ships made for the Falkland Islands as quickly as they could.

The naval success caused a sensation in Germany and dismay in Britain.

See the entry for the Falklands Battle to take up the account.

Spee was under no illusions as to the precariousness of his position. He forbade the holding of any celebrations by the German community in Valparaiso and when presented with a bouquet of flowers said they could be put on his grave.

Medals and Plaque commemorating the Battle of Coronel awarded for Stoker 2nd Class John Smith. R.N. of HMS Good Hope, killed in action at the Battle of Coronel on 1st November 1914 in the First World War

Anecdotes and traditions from the Battle of Coronel:

- Medals were issued in Germany commemorating the German victory at Coronel.

- HMS Good Hope and HMS Monmouth were ships of the reserve at the outbreak of war, without crews and in dock. Both ships were mobilised and provided with crews, largely Royal Navy reservists. Four midshipmen from the Royal Canadian Naval College were drafted to Good Hope. The Battle of the Coronel took place before either ship’s crew could settle down and in particular before they could become proficient in gunnery.

Medal issued in Germany celebrating the German victory at the Battle of Coronel on 1st November 1914 in the First World War

Reverse of Medal issued in Germany celebrating the German victory at the Battle of Coronel on 1st November 1914 in the First World War

- As an interesting insight into the difficulties faced by the Royal Navy on the outbreak of war; the Battleship HMS Triumph lay demobilised and without a crew in Hong Kong harbour. On the mobilisation of the fleet four Royal Navy gunboats were laid up in the Yangtze River and their crews transferred to the Triumph. This left a shortfall that was filled with two officers and one hundred and six soldiers from 2nd Duke of Cornwall’s Light Infantry, stationed in China. After a month of naval service the soldiers were returned to their battalion, replacement sailors arriving from Britain.

- The suggestion was made in contemporary accounts of the Battle of Coronel that the Germans failed to make any effort to rescue survivors from the Good Hope and the Monmouth. In particular a story emerged that a German pastor in Chile asked why there were no British survivors and was told by German seaman that they were ordered by their officers to make no rescue effort although it would have been possible. In fact by the time the two ships sank it was dark and the sea and weather conditions such that no boat could have been launched. Corbett makes the comment that boats could not be launched.

- Admiral Graf von Spee was accompanied in his squadron by his two sons, both lieutenants: Otto on Nürnberg and Heinrich on Gneisenau.

- Many of the large ships in the Pacific of all nationalities carried armour manufactured by Krupp of Germany.

- In 1918 the United States Naval Authorities named a new neighbourhood for dockyard workers at Portsmouth, Virginia, ‘Cradock’ in memory of Admiral Cradock.

- Captain Kinnier in SS Ortega was carrying 300 French reservists returning to France when he was fired on by SMS Dresden on 23rd September 1914. Kinnier put on all speed and headed straight into the uncharted and highly dangerous Nelson Strait, thereby escaping Dresden. The Admiralty appointed Kinnier an RNR Lieutenant and awarded him the DSC.

References for the Battle of Coronel:

• Naval Operations in the Great War Volume 1 by Sir Julian Corbett

• Jane’s Fighting Ships of World War 1

• Times History of the Great War Volume 2

Photograph of some of the officers of HMS Good Hope taken in the Falkland Islands in October 1914. None of these officers survived the destruction of the Good Hope at the Battle of Coronel on 1st November 1914 in the First World War. The three Canadian midshipmen are third, fourth and seventh in the front row (Mid. A. W. Silver, RCN; Mid. M. Cann, RCN; Mid. W. A. Palmer, RCN).

The previous battle in the First World War is the Texel Action

The next battle in the First World War is the Battle of the Falkland Islands