The victory of the English over the Scots in the ‘War of the Rough Wooing’ on 10th September 1547

The previous battle of the Anglo-Scottish Wars is the Battle of Flodden

The next battle in the British Battles series is the Spanish Armada

To the Anglo-Scottish Wars index

War: the period of the extended Anglo-Scottish Wars in Tudor times known as the ‘Eight Years War’ or the ‘War of the Rough Wooing’.

Date of the Battle of Pinkie: 10th September 1547

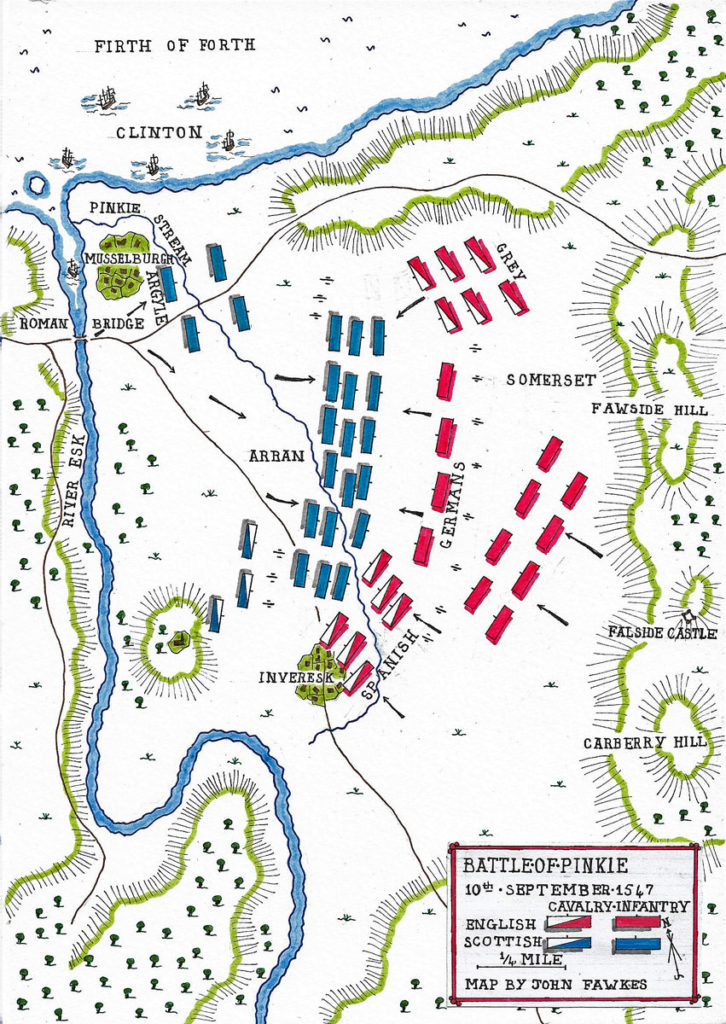

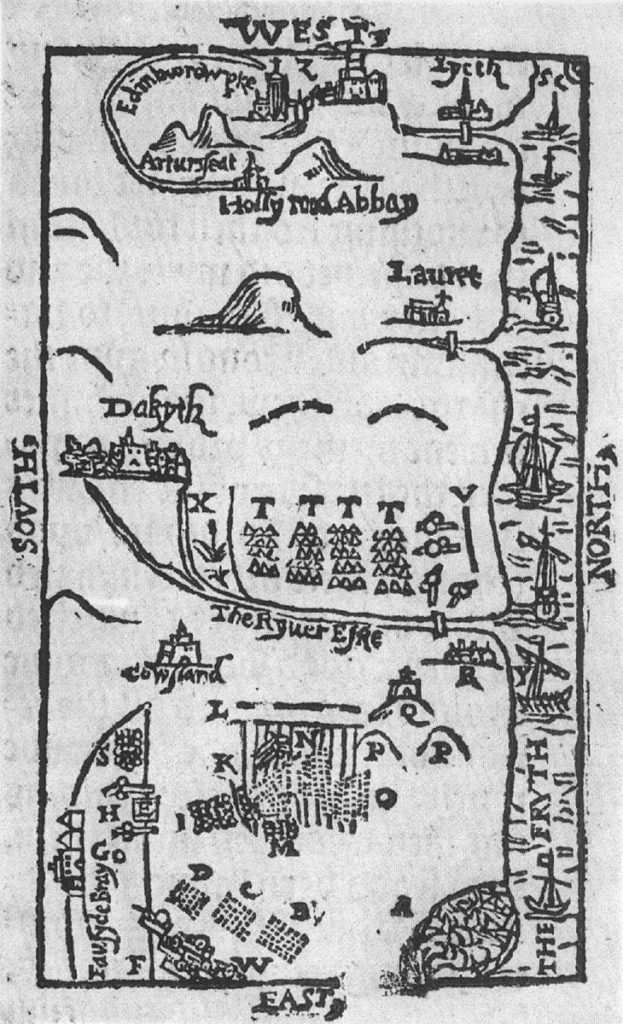

Place of the Battle of Pinkie: On the east bank of the estuary of the River Esk at Musselburgh on the east coast of Scotland.

Combatants at the Battle of Pinkie: English against the Scots.

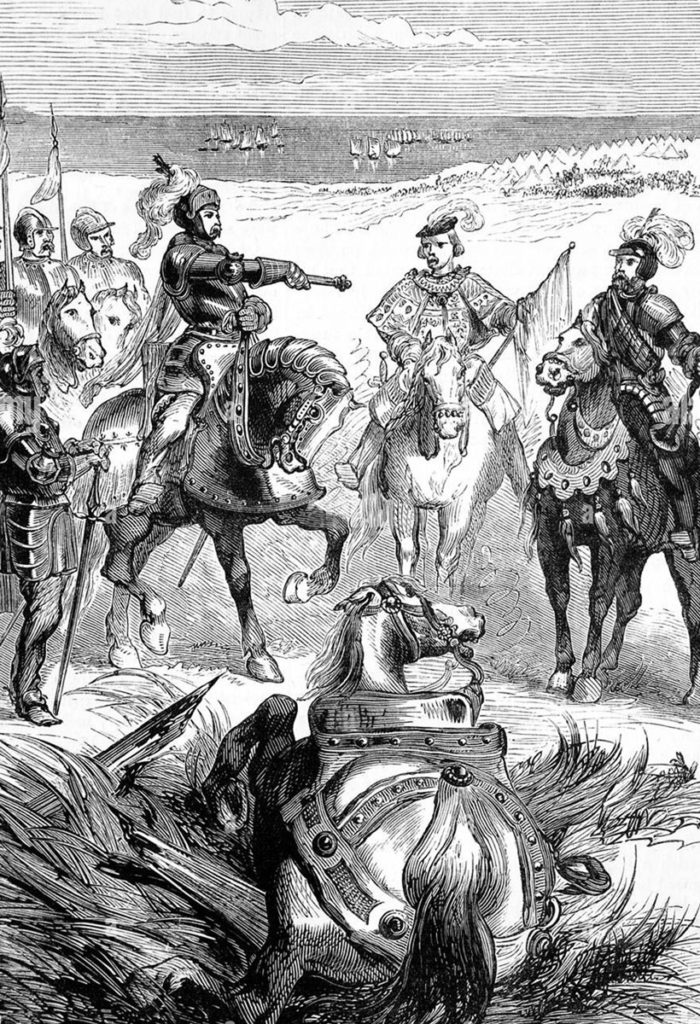

Commanders at the Battle of Pinkie: Edward Seymour, Duke of Somerset, the Lord Protector of England during the minority of King Edward VI, led the English army. James Hamilton, Earl of Arran, Regent of Scotland, led the Scottish army.

Size of the armies at the Battle of Pinkie: The English army numbered around 14,000 men. The Scottish army numbered around 25,000 men.

Uniforms, arms and equipment at the Battle of Pinkie:

While the Scottish army heavily outnumbered the English, the Scottish cavalry were few, around 1,000 Border horsemen or Reivers, experienced in fighting, but equipped for banditry rather than battle, armed with swords and spears, but wearing rudimentary armour and mounted on poor quality horses or ponies.

The main body of Scottish infantry fought with the 6-yard-long pike introduced into Scotland by the French before the Battle of Flodden and adopted with enthusiasm by the Scots who hoped to emulate the success of the weapon in the hands of the Swiss.

The Scots were by this time experienced in the use of the pike in battle and readily adopted the most appropriate formation, three ranks presenting a hedgehog effect to an attacking enemy.

‘The first rank knelt, the second sloped, the third stood erect; but all three with their weapons pointed at three angles towards the enemy.’

Otherwise, the ordinary soldiers of the Scottish army were armed with whatever weapons they could bring to war, including the agricultural implements from their everyday work.

Patten described the Lowland infantry as being clad ‘all alike in jackes covered with white leather, doublets of the same or white fustian, and most commonly all white hosen.’

There was a sprinkling of archers in the Scottish ranks.

The highland clans fought with target shield and sword, many armed with the heavy two-handed weapon.

Whereas the Scottish army was armed in the style of the Middle Ages, the English army boasted equipment, weapons and tactics from the early Renaissance, particularly firearms.

The English army was described by Patten as the ‘best ordered that had ever entered Scotland’.

Both armies comprised artillery, but the English train was larger in numbers and more sophisticated, with 15 guns.

In the English army were three important bodies of mercenaries: a force of Spanish cavalry, commanded by Pedro de Gamboa, heavily armoured and armed with long wheel-lock pistols.

The second, German infantry, commanded by Peter Mewtas, armed with the arquebus, an early form of musket fired with a bipod support.

Both these bodies of mercenaries wore extensive armour, in the case of the Spanish cavalry the horses being ‘barded’ or protected by horse armour.

An additional corps d-elite was the King’s band of Gentlemen Pensioners commanded by Sir Thomas Darcy.

A further mercenary corps was a body of some 2,000 mounted men-at-arms from Boulogne, captained by Edward Shelley. These well-drilled and disciplined horsemen were English ex-members of the Boulogne garrison, held at this time for the English king, along with the neighbouring port of Calais.

The main cavalry force in the English army was the 4,000 mounted men-at-arms commanded by Lord Grey of Wilton, Lieutenant of Boulogne and Sir Ralph Vane, the High Marshal.

Sir Francis Bryan led the 2,000 English light horse.

The rest of the army was made up of infantry soldiers with a wide variety of weapons and a substantial number of archers armed with the long bow, the most significant weapon for English armies throughout the late Middle Ages.

The English army was supported by a fleet of 30 ships of war and 32 transports, commanded by Lord Clinton, which lurked in the Esk Estuary and fired on the Scots as they crossed the River Esk, moving towards the English at the beginning of the battle and away from them in flight at the end.

Winner of the Battle of Pinkie:

The Scots were heavily defeated.

Events leading to the Battle of Pinkie:

In his later years King Henry VIII of England schemed to arrange the marriage of his infant son Edward to Mary Queen of Scots, also an infant.

Broadly, the Scottish aristocracy, although many entered into a league to work towards the marriage, opposed the match, which was likely to lead to union between England and Scotland, as Henry VIII intended.

The Scots, on the whole, preferred the proposal put forward by the King of France of a marriage between Mary and his son.

Such an arrangement was in keeping with the Auld Alliance between Scotland and France and would leave Scotland independent of England.

In his later years, Henry VIII waged war against France and France needed the assistance of its ally, Scotland, to divert the attention of the English by invasion across the border.

King Henry VIII died in 1547, leaving instructions that the match between the now King Edward VI and Queen Mary be pursued, in spite of the Scottish lack of enthusiasm.

The Duke of Somerset, the Protector of the infant King Edward, resolved to bring matters to a head and force the Scots to accept the match by attacking Scotland.

The Earl of Arran, Regent of Scotland in the light of the Queen’s infancy, worked hard to prepare for the impending invasion.

Somerset marched his army into Scotland along the east coast, shadowed by an English fleet commanded by Lord Clinton, in September 1547, his troops laying waste to the countryside as they passed.

The Earl of Arran assembled the Scottish army at Inveresk on the northern bank of the River Esk on the North Sea coast, covering the city of Edinburgh.

The River Esk was wide and deep with high banks, creating a strong defensive position for the Scots army encamped on its north side.

The Earl of Huntly commanded the Scots left wing.

Next in the Scottish line was the Earl of Argyll with 3,000 Highland bowmen.

Arran commanded the Scottish centre, with the main battle along the Edmonstone Edge.

The Earl of Angus commanded the vanguard, positioned on the right, with the Scottish cavalry on his right, commanded by the Earl of Home, protected by a bog to their front.

The main crossing point over the River Esk was the old Roman bridge near the coast, which the Scots barricaded and covered with cannon and archers, that is other than at low tide when a number of fords across the estuary became usable.

The English encamped on the raised ground to the south-east of the river.

A stream, the Pinkie, meandered across the valley before flowing into the River Esk.

The English Fleet anchored off Musselburgh at the entrance to the Esk Estuary. The commander, Lord Clinton, came ashore to confer with Somerset, providing him with information on the Scottish deployment behind the Esk.

On the morning of 9th September 1547, the Scottish cavalry under the Earl of Home crossed the River Esk and galloped about in front of the English lines, challenging the English to give battle.

Somerset ordered Lord Grey to attack the Scots with the English heavy cavalry.

A fierce combat took place between the ill-equipped and outnumbered Scottish horsemen and the English men-at-arms, the Scots being overwhelmed and driven back.

The Earl of Home fell wounded from his horse and was taken prisoner with his son and bodyguard, with two other gentlemen and two priests.

Later that day, Somerset conducted a reconnaissance of the ground and saw that there was a small hill near the sea which overlooked the Scottish camp across the river. On this hill was the church of Inveresk.

A lane led to the west roughly following the direction of the River Esk.

This lane led up to another area of raised ground on a feature called the Fawside.

Through the middle of this ground ran the Pinkie stream.

Somerset resolved to position his artillery on these two features to fire on the Scots across the river once the battle was begun.

On his way back to camp, Somerset was overtaken by a mounted Scottish herald with a trumpeter.

The herald informed Somerset that he brought a message from the Earl of Arran.

After proposing an exchange of prisoners, the herald informed Somerset that Arran proposed that the English army be permitted to withdraw across the border to avoid an ‘effusion of Christian blood’.

Somerset rejected this proposal.

The herald said that in that case the Earl of Arran proposed that the issues between the two countries should be settled by a combat between the two commanders with a small group of knights.

Somerset rejected this proposal, pointing out that as the Protector for the infant King of England he could not possibly subject himself to such a risk.

That night the confident Scottish leaders played dice for the disposal and ransom of the senior Englishmen they expected to capture in the battle to come.

Somerset wrote to Arran saying that the English army would withdraw from Scotland if the Scots undertook to keep Mary Queen of Scots in Scotland until she came of age, thereby preventing her from marrying the French prince.

This proposal was rejected.

Account of the Battle of Pinkie:

In the early hours of 10th September 1547, the English army was on the move, advancing towards the Scottish positions.

The advance was angled towards Inveresk and the coast.

It is said that the Scottish Regent, the Earl of Arran, misread Somerset’s intentions, believing his plan to be to embark his army on the English fleet and escape defeat by the significantly more numerous Scottish army.

Whatever the cause, the Scots left their powerful position behind the Esk and swarmed across the river, many by the Roman bridge, others by fords and other crossing points.

The two armies now confronted each other on the southern bank of the River Esk athwart the Pinkie stream.

Arran commanded the Scottish centre, comprising 18,000 men from the clans of Strathearn, the men of the Lothians, Kinross and Stirlingshire, described as the flower of the Scottish infantry; with them a corps of 800 men from Edinburgh led by their Provost.

The right wing comprised 6,000 West Highlanders and men from the Isles, commanded by the Earl of Argyle and the chiefs of Macleod and Macgregor.

Scottish artillery flanked the right wing.

On the Scottish left wing were 10,000 men of the eastern counties commanded by the Earl of Angus.

This division was supported by more artillery and light horse.

In the ranks of the Scots left wing marched a contingent of 1,500 monks, wearing armour and surcoats marked by a cross, the colours marking them as Black, Grey or Red Friars.

These monks or friars were drawn into battle through fear of the spread of the English Reformation in Scotland.

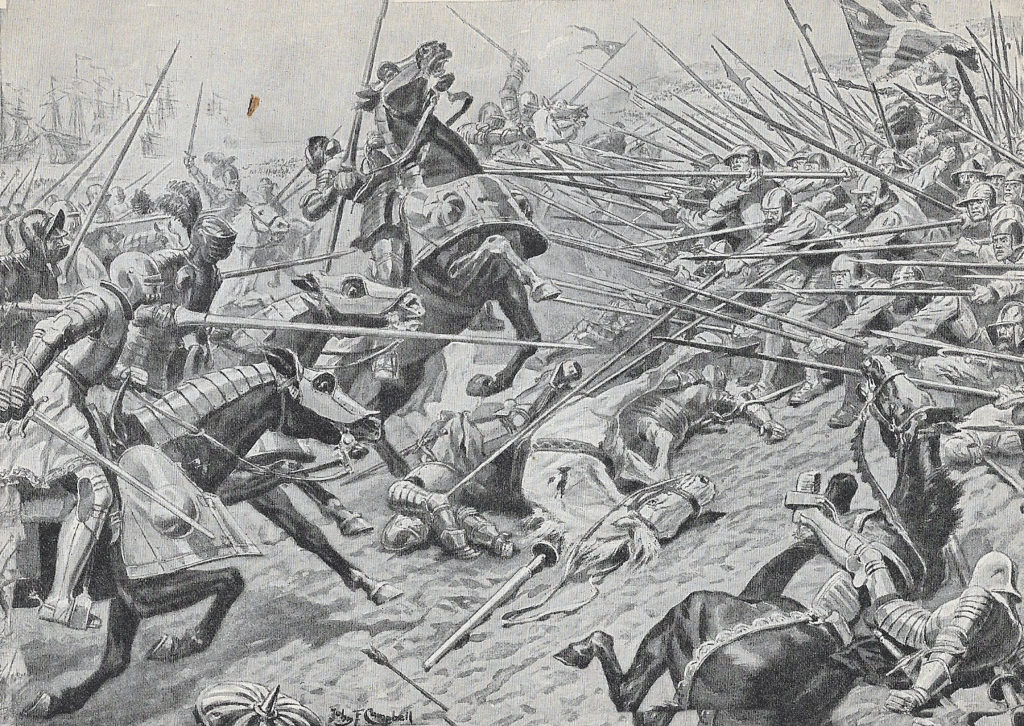

Once across the Esk, the Scottish infantry converged to form a bristling phalanx of spearmen.

That is other than Argyle’s highlanders, who came under a heavy artillery fire as they crossed the river and left the battlefield.

After a rapid advance the massed Scottish pikemen in their huge schiltron halted.

The English army was in three columns, advancing in parallel.

The Earl of Warwick commanded the first column, the Duke of Somerset the second column and Thomas, Lord Dacres commanded the third.

The English cavalry charged Huntly’s division on the Scottish right, but were thrown back.

A second cavalry attack was launched against Arran’s troops, but again the horsemen were repelled by the steady ranks of spears.

During this combat the English Royal Standard, carried by Sir Andrew Flammock, was nearly taken. Sir Andrew escaped from the struggle with the Standard less its staff.

The English cavalry attack, while failing to penetrate the ranks of the Scottish spearmen, brought their advance to a halt, enabling Somerset to bring up the slow-moving English artillery train.

The English sakers were brought into action at a range of 350 paces, from where their discharges wrought havoc among the closely packed Scottish spearmen.

Soon after the bombardment by the English cannon began, the Spanish mounted troops rode down the flanks of the Scottish schiltron discharging their pistols into the packed Scottish ranks.

The Spanish horsemen were supported in their attack by the German hackbutiers under Sir Peter Mewtas, who marched forward and fired volleys into the Scottish spearmen.

Somerset continued the assault by bringing forward the English infantry, whose archers began a rain of arrows on the reeling Scots schiltron.

A heavy rainstorm broke over the battlefield, increasing the confusion in the Scottish ranks.

Seeing the Scottish army beginning to disintegrate, Somerset launched the English cavalry in a further attack.

The English cavalry charge was the final blow. The Scots army began to break up and flee the field.

Some Scots fled towards Dalkeith, others across the Esk in the direction of Edinburgh and others along the seashore heading for Leith.

The English broke ranks for the pursuit, slaying the fleeing Scots in their thousands.

Lord Clinton’s English fleet came further into the estuary mouth and opened fire on the Scots fleeing across the Esk, adding to the slaughter.

Casualties at the Battle of Pinkie:

Scottish casualties are said to have been around 10,000 killed and wounded, many in the lengthy pursuit after the Scots army broke up.

Most of the monks were slain and their banner was found on the field of battle.

Among the more prominent Scots dead were Lords Elphinstone, Cathcart and Fleming, Sir James Gordon of Lochinvar, Sir Robert Douglas of Lochleven and many others, including Findlay Mhor Farquharson., of Invercauld, the bearer of the Royal Standard of Scotland.

English casualties are said to have been around 500 men killed, mainly from the heavy cavalry.

Among the more prominent English casualties were Edward Shelley, Lieutenant of the Bulleners, Ratcliff, Preston, Clarence and other veteran English officers of the heavy cavalry, killed during the furious attacks on the Scottish pikemen.

Follow-up to the Battle of Pinkie:

After the battle, Somerset remained in the neighbourhood of Edinburgh for a week before marching his army back to England.

Mary Queen of the Scots married the son of the French king in due course.

The English victory seemed to have achieved little, other than to further inflame the hatred between the two nations.

Anecdotes and traditions from the Battle of Pinkie:

- A detailed account of the English invasion of Scotland was published by Master William Patten, the Judge-Marshal to the invading English army, under the title ‘The Expedition into Scotland of the most worthy fortunate Prince, Edward, Duke of Somerset, made in the First Yere of his Maistie’s Most Prosperous Reign, and set out by waye of Diarie by W. Patten, London. Vivat Victor! Out of the Parsonage of St. Mary Hill, in London, this xxviii of January, 1548.’

- The Battle was called ‘The Battle of Pinkie Cleugh’ by the Scots and remembered as ‘The Black Saturday of Pinkie’. The English called the Battle, Inveresk or Musselburgh.

References for the Battle of Pinkie:

Battles in Britain 1066 to 1547 Volume 2 by William Seymour

British Battles by Grant.

British Battles on Land and Sea

The previous battle of the Anglo-Scottish Wars is the Battle of Flodden

The next battle in the British Battles series is the Spanish Armada

To the Anglo-Scottish War index