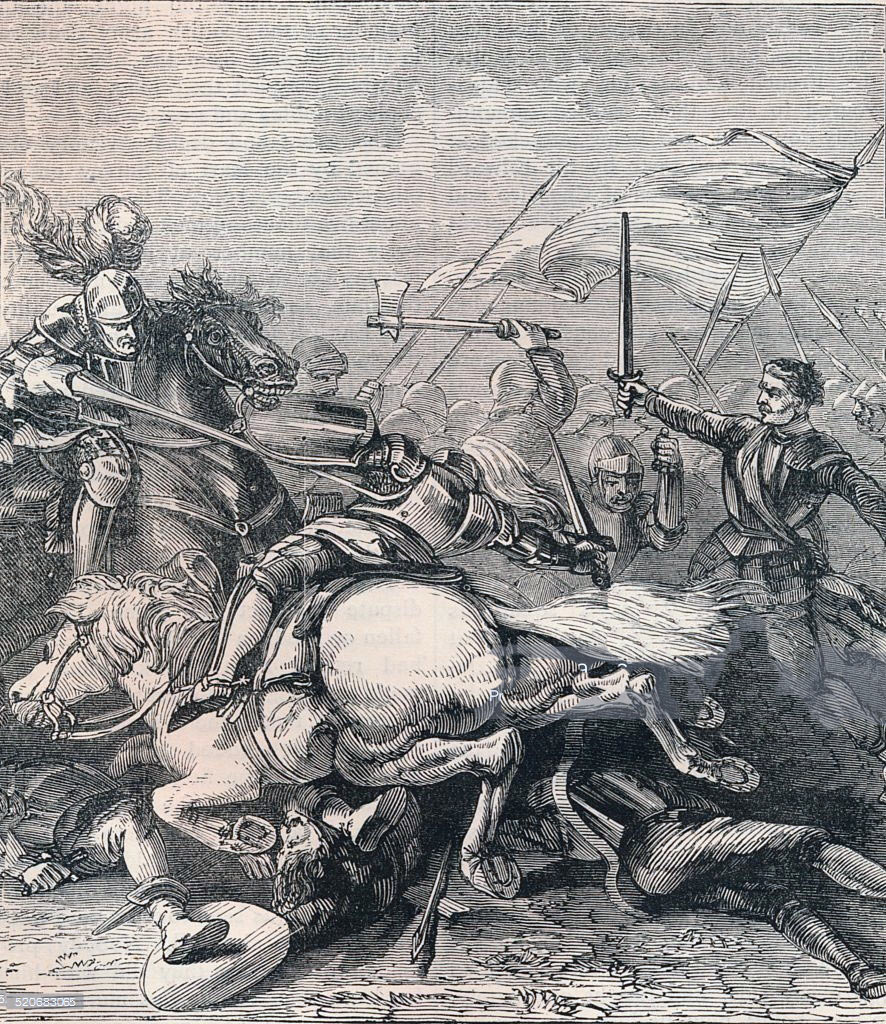

The defeat on 9th September 1513 at the hands of the English that annihilated a generation of Scottish aristocracy including King James IV

News of the Battle of Flodden on 9th September 1513 brought to Edinburgh: picture by Thomas Jones Barker

![]() 72. Podcast on the Battle of Flodden: the defeat on 9th September 1513 at the hands of the English that annihilated a generation of Scottish aristocracy including the Scots king, King James IV: John Mackenzie’s britishbattles.com podcasts

72. Podcast on the Battle of Flodden: the defeat on 9th September 1513 at the hands of the English that annihilated a generation of Scottish aristocracy including the Scots king, King James IV: John Mackenzie’s britishbattles.com podcasts

The previous battle in the British Battles series is the Battle of Bosworth Field

The next battle in the Anglo-Scottish War is the Battle of Pinkie

To the Anglo-Scottish War Index

War: Anglo-Scottish Wars

King James IV of Scotland, the commander of the Scottish army at the Battle of Flodden in 1513; his death at the battle, with many of his nobles and soldiers, plunged Scotland into crisis for many years

Date of the Battle of Flodden: 9th September 1513

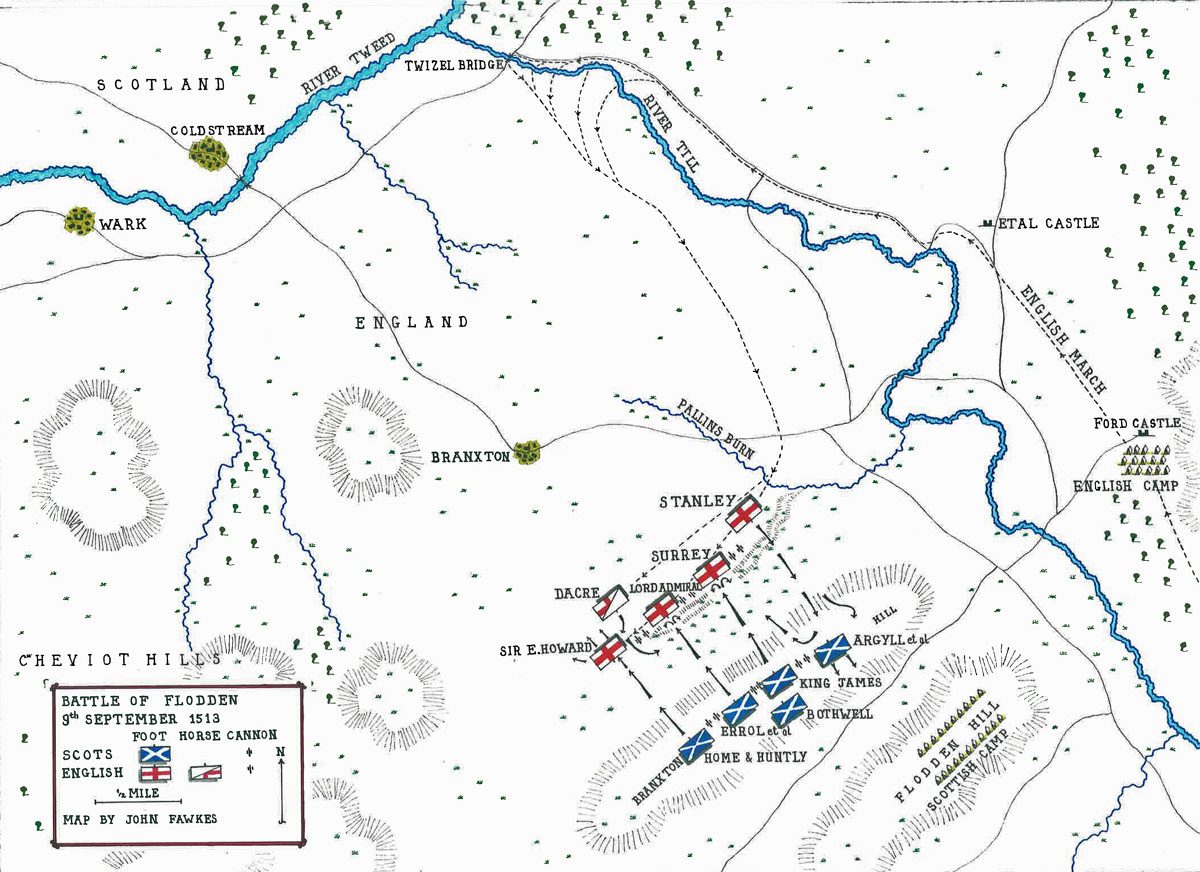

Place of the Battle of Flodden: The South Bank of the River Tweed on the border between Scotland and England.

Combatants at the Battle of Flodden: An invading Scottish army against an English army.

Generals at the Battle of Flodden: King James IV commanded the Scottish Army and the Earl of Surrey commanded the English Army.

Size of the armies at the Battle of Flodden: The 2 armies were much the same size, at 20,000 to 30,000 men, the English army larger than the Scottish.

Winner of the Battle of Flodden: The Scottish were overwhelmingly defeated by the English, with the death of King James IV and many of his accompanying Scottish nobles and citizens.

Uniforms, arms and equipment at the Battle of Flodden:

The 16th Century saw the transition across Europe from Medieval warfare with its feudal formations to armies with a more modern form; a change that was quicker on the mainland of Europe, where new forms of battlefield tactic were being introduced by the Swiss, Spanish and the Swedes.

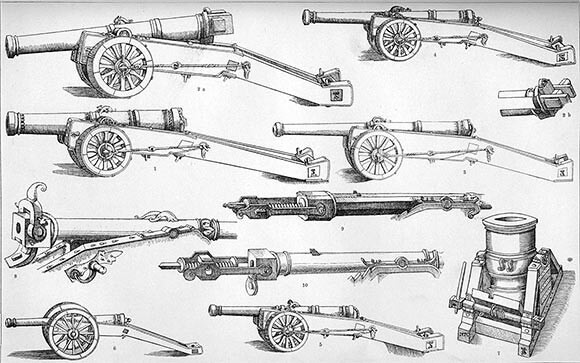

Both sides at Flodden used cannon on the battlefield, although their size and weight made them difficult to manoeuvre. It is said that the 30 Scottish guns, 17 of them large, required 400 oxen and 28 horses to draw them and the ammunition. Loading was slow, propellant was unreliable and the solid projectiles caused little damage to troop formations. Cannon was at its most useful against town and castle walls.

English archers in battle with the longbow in the Middle Ages: Battle of Flodden on 9th September 1513

The Scottish cannon was considered of better quality than the English. The Scottish cannon master, Robert Borthwick, cast his guns and oversaw their use on the battlefield. Seven of his guns were known as the ‘Seven Sisters of Borthwick’. At Flodden, the English guns were more numerous and better served than the Scottish. While the Scottish cannon were cast, the English were made using the outdated system of hoops and bars.

Robert White described the Scots army, in the Cambridge History of the Renaissance: “The principal leaders and men at arms were mounted on able horses; the Border prickers rode those of less size, but remarkably active. Those wore mail, chiefly of plate, from head to heel; that of the higher ranks being wrought and polished with great elegance, while the Borderers had armour of a very light description. All the others were on foot, and the burgesses of the towns wore what was called white armour, consisting of steel cap, gorget and mail brightly burnished, fitting gracefully to the body, and covering limbs and hands. The yeomen or peasantry had the sallat or iron cap, the hauberk or place jack, formed of thin flat pieces of iron quilted below leather or linen, which covered the legs and arms, and they had gloves likewise. The Highlanders were not so well defended by armour, though the chiefs were partly armed like their southern brethren, retaining, however, the eagle’s feather in the bonnet, and wearing, like their followers, the tartan and the belted plaid. Almost every soldier had a large shield or target for defence, and wore the white cross of Saint Andrew, either on his breast or some other prominent place. The offensive arms were the spear five yards in length, the long pike, the mace or mallet, two-handed and other swords, the dagger, the knife, the bow and sheaf of arrows; while the Danish axe, with a broad flat spike on the opposite side to the edge, was peculiar to the Islemen, and the studded targe to the Highlanders.”

King James IV met the feudal army of Scotland on the Burgh Muir at Edinburgh. He planted his Royal Standard in the Hare Stone, by the highway leading to Braid.

The core of the army was the body of Scottish nobility, most of whom attended with their sons and retainers, except, by custom, the oldest sons, who remained at home to continue the family line in case of disaster; an appropriate precaution in the case of Flodden.

The rest of the army was made up of those men liable for military service; that is every small or large landowner with his family and retainers.

A Scottish Act of Parliament, passed in 1491, required every man to have provisions for 40 days. The Act stated that every possessor of £10 worth of land or more “shall have a helmet or salade, gorget or pisane, and mail for the limbs, a sword, spear and dagger.”

“All other yeomen of the realm, betwixt sextie and sextene, shall have sufficient bowes and sheaves, sword, buckler, knife, speare, or any gude axe instead of bow.”

“Every man must be accoutered in white harness or good jacks, with gloves of plate, and well-horsed “correspondent to his lands and goods.”

The best sword blades and armour were made by Andrea de Ferrara, the renowned Scottish armourer. A Ferrara blade was required to bend double and spring back into true and continued to be much sought after by Scottish officers into the 19th Century.

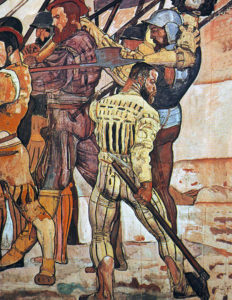

The arrival of two French dignitaries, La Motte and D’Aussi, brought a significant change in the Scottish army, as they introduced the long pike, used to such devastating effect by the Swiss Cantoniers.

This was an unfortunate move, as there was not time for the Scottish soldiers to become sufficiently adept with this cumbrous weapon (the pike was 5 yards long) and to learn to act in concert, as the long pike required to be effective.

The Scottish army possessed little in the way of cavalry, other than the mounted nobles.

A strong Highland contingent joined King James IV’s army. They remained armed in their traditional manner, with swords, daggers and target shields or simply with bill hooks for the poorer men.

The dignitaries in the Scottish army wore good suits of armour in battle.

The English army had its own train of artillery, which in the event did better service than its more technically advanced Scottish equivalent.

Swiss soldiers of the period carrying the 5 yard pike, that the French introduced into the Scots army for the invasion of England in 1513 and that proved so inappropriate at the Battle of Flodden on 9th September 1513

As with the Scots, the English army had few mounted men, other than Lord Dacre’s body of Northern ‘Prickers’ or light horsemen.

A high proportion of the English soldiers carried and were adept in the use of the longbow, King Henry VIII’s favourite weapon. The longbow delivered a volley of arrows up to 600 yards or aimed shots at 200 yards. The longbow was a decisive weapon at Flodden, as the Scottish army did not have sufficient bowmen to counter the English archers.

Robert White described the armaments of the English army: “.. Again, the nobility, knights, and men at arms were on horseback, each accompanied by attendants according to his rank. They wore also plate armour from head to foot, some sorts of which, belonging to superior men, were brightly polished and occasionally inlaid with silver or gold, while their steeds were richly caparisoned with housings embroidered with the devices of their respective owners.

“Among the spearmen and billmen, who were on foot, plate mail had given way to armour, similar to that mentioned previously in the Scottish army, being composed of small steel or iron plates, of a square form, overlapping each other, and quilted either upon or within linen or leather. Such a covering was flexible, yielding to every turn of the body, and kept the wearer often safe from the thrust of a spear or the stroke of a sword.

“Many of the archers wore the brigantine or jack, like the spearmen or billmen, while others, as in the preceding reign, were clad in a shirt of chain mail with very wide sleeves, and over this a small vest of red cloth laced in front, with hose on the legs and braces on the left arm.

“The horsemen had the mace or battle axe in addition to the lance, the sword and the dagger. The spearman, whose name indicated the weapon he bore, had also the sword and dagger, and indeed the two latter were girded on almost every soldier in the army. The two-handed sword was not in much request; but of the several mentioned, the most effective was the large bill – a strong blade with an edge from eighteen to twenty-four inches long, mounted on a handle of sufficient length, and wielded by a powerful and able-bodied peasantry of England.

“The archer, again, with his bow cased in coarse cloth, and a sheaf of arrows, beside the dagger and sword, on the hilt of which was usually a small buckler, had often a leaden moll which he bore on his back, and as the bow was useless in close combat, such a hammer was often fatal as the great bill.

Swiss soldiers of the period carrying the 5 yard pike, that the French introduced into the Scots army for the invasion of England in 1513 and that proved so inappropriate at the Battle of Flodden on 9th September 1513

“According to the fashion of the previous reign, white was the prevailing hue of the whole army, save that of the mariners brought by the admiral, and all wore the red cross of St George except a dignitary of the church or an officer at arms.”

Background to the Battle of Flodden:

King James IV came to the throne of Scotland in 1488 at the age of 15, following a sharp civil war with his father, King James III. James IV’s followers defeated his father at the Battle of Sauchieburn and killed him, contrary to the son’s specific instructions. James IV is reputed to have born the burden of this regicide badly throughout the rest of his life, wearing an iron chain around his waist, with an additional ring added each year, as penance and frequently going into religious retreat.

Otherwise, James IV was an effective and popular King of Scotland.

In 1502, James IV married Margaret Tudor, daughter of Henry VII, King of England. The marriage assisted in keeping the peace between the two countries, although James IV made the mistake of supporting the pretender, Perkin Warbeck, in his claim to the English throne, against Henry VII, as one of the Princes in the Tower.

James IV stood by the ‘Auld Alliance’ between Scotland and France, but declined to be drawn into war with England for much of his reign.

In 1509, King Henry VII of England died and was succeeded by the bombastic and difficult Henry VIII. Initially, James IV managed to avoid any substantial problem with the new King of England, although there were minor disputes: Henry VIII refused to deliver the jewels Henry VII bequeathed to his daughter, Margaret and English ships attacked and killed Sir Andrew Barton, one of James IV’s favoured ship captains, on the pretext that he was a pirate.

Margaret Tudor, daughter of King Henry VII, sister of King Henry VIII, Queen of Scotland and wife of King James IV. In 1513 Margaret watched James leave for the war from a tower of Linlithgow Palace, now called Margaret’s Bower: Battle of Flodden on 9th September 1513

In 1511, King Henry VIII joined the Holy League against France, with the Pope, Emperor Maximillian, Spain and Venice. England would soon be at war alongside these states, precipitating a crisis in relations with Scotland.

In 1512, King James IV formally renewed the ‘Auld Alliance’ between Scotland and France. If England attacked France, Scotland would be bound to fight alongside France.

In early 1513, James IV formally offered peace to Henry VIII, provided he did not attack France. This proposal was rejected by Henry.

In the meantime, ties between France and Scotland were strengthened. A French envoy, La Motte, came to the Scottish court, bringing wine, gun powder and other munitions, together with some English ships he captured on his journey.

The French Queen, Anne of Brittany, sent James IV 14,000 crowns and a ring of gold and turquoise, with a letter couched as if to a lover, imploring James IV to be her ‘true knight’ and to invade England, if England attacked France, if only up to 3 feet in distance.

Queen Margaret beseeched King James not to invade England and asked “Why he preferred the Queen of France to her his wife, the mother of his children, whom he had wedded in her girlhood.”

Account of the Battle of Flodden:

The concerns of the French court were justified, as, in June 1513, King Henry VIII with a large army invaded France. In compliance with his treaty obligations, King James IV prepared to invade England.

James IV’s Queen and his nobles were deeply worried and urged James not to take such a drastic step. In a final attempt to avoid war with England, James IV, on 26th July 1513, sent his Lyon King of Arms to Henry VIII, requiring him to withdraw from France. Henry VIII sent back a bombastic and dismissive reply, which did not reach King James before the Battle of Flodden.

To his worried nobles, King James said that Henry was gone to France with all England’s soldiers leaving no one behind capable of defending the country.

King Henry was, throughout, fully aware that the Scots were likely to invade England. Before leaving for France, Henry said to the Earl of Surrey, when appointing him Lord Lieutenant of the North, ‘My Lord, I trust not the Scots, therefore I pray you be not negligent.’ Surrey was sixty nine, and showed himself far from negligent (Surrey was the son of the Duke of Norfolk, who had lost his dukedom by fighting for Richard III against Henry VII, at Bosworth Field, in 1485).

King James pressed ahead with plans to invade England, in accordance with his treaty obligations to France, summoning all Scots liable for military service to gather at Edinburgh. Queen Margaret and many of the nobles were dismayed at the prospect of what was seen as an unnecessary war with England.

Immediately before King James left his palace for the invasion of England, an incident occurred in St Catherine’s Aisle of the Chapel Royal at Linlithgow Palace. It was described by a contemporary account:

“There entered by a door a man of strange and solemn aspect, clad in a blue weed, belted with a piece of linen. The man approached King James and said ‘Sir King. My mother has sent me to thee, desiring thee not to pass at this time where thou art purposed, for if thou dost, thou wilt not fare well in thy journey, nor any who pass with thee…. “

The man vanished through the hands of the attendants who tried to stop him. The incident was thought to be a device by Queen Margaret. It had no effect on the King.

King James IV of Scotland confers with his advisers before the Battle of Flodden on 9th September 1513

Margaret withdrew to a tower in Linlithgow Palace to watch King James leave for Edinburgh and the invasion of England. The tower is known as Queen Margaret’s Bower. This was the last time the Queen saw her husband.

James’ intention was a limited attack, to compel Henry to give up the invasion of France and return to England. It may be that James expected the English would be unable to raise an army sufficient to resist his and that there would be little opposition to his limited operation.

James was a popular king and his call to arms was enthusiastically received in all quarters of Scotland. The Scottish Army began to gather at Edinburgh in August 1513.

The place of assembly was the Burgh Muir or Borough Moor.

It is said that the army the King gathered was the largest and best equipped army ever to leave Scotland for an invasion of England.

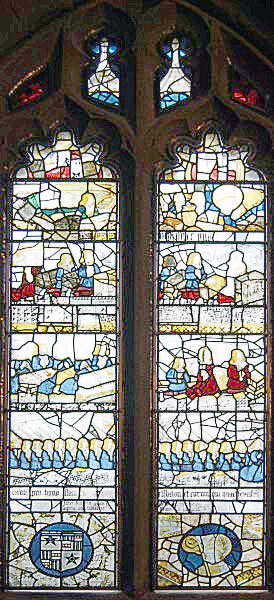

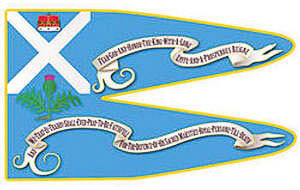

“The Standard of the Crafts within the Burgh” of Edinburgh, known colloquially as “The Blue Blanket”, carried in war by the tradesmen of Edinburgh when led by their King: Battle of Flodden 9th September 1513

The tradesmen of Edinburgh possessed a banner, “The Standard of the Crafts within the Burgh”, known informally as ‘The Blue Blanket’, said to have been hand embroidered by the then Queen and awarded by King James III for assisting his escape from Edinburgh Castle.

The Blue Blanket was displayed when an audience was sought with the King or when the tradesmen of Edinburgh followed their King to war. In August 1513, Provost Alexander Lauder of Blyth led out the burgesses of Edinburgh, to join their King’s army on the Burgh Muir. Few would return.

As the Scottish cannon were being brought during the night to the assembly point, a strange wailing voice was heard at the City Cross, known as the ‘Summons of Platcock’, giving the list of nobles who would not return from the campaign. It proved prescient. All named died but one, who threw down a coin as a plea for release from the list.

“The Standard of the Crafts within the Burgh” of Edinburgh, known colloquially as “The Blue Blanket”, carried in war by the tradesmen of Edinburgh, when led by their King: Battle of Flodden 9th September 1513

A French contingent commanded by the Comte D’Aussi provided training to the Scottish soldiers in the weapon being widely adopted in Europe following its successful use by the Swiss, the long 5 yard pike.

Contingents joined James IV’s army from the Borders, the Lowlands, the Highlands and the Isles. Several clans turned out to fight; Macleods, Mackenzies, Macleans and Campbells. Estimates for the size of the army that left Edinburgh range between 30,000 and 40,000 men.

The army was quickly affected by desertion, particularly once there had been an opportunity to gather loot.

In early August 1513, The English Borderers carried out a raid into Scotland. Choosing not to wait for his King, Alexander, Lord Home, who held the posts of Warden of the Marches and Chamberlain of Scotland, gathered a force of some 3,000 Borders horsemen and carried out a retaliatory raid into England. After a successful foray, Home was returning with substantial booty when, on 13th August 1513, he was ambushed at Milfield by Sir William Bulmer, whose archers killed some 400 Scots, took 200 prisoners and put the rest to flight. The English recovered all the booty taken by Home’s men and Home’s foray was labelled by the Scots the ‘Ill Raid’.

On 22nd August 1513, the Scots army crossed the River Tweed into England. Probably James’ eventual aim was to march on Newcastle. On the south bank of the Tweed, the Scots captured Wark Castle and marched east down the Tweed to besiege Norham Castle, which surrendered after 6 days.

James resumed his march to the south-east capturing the castles of Etal and Ford, on the east bank of the River Till.

Ford Castle on the River Till in Northumbria, captured by King James IV and burnt before the Battle of Flodden on 9th September 1513

Ford Castle belonged to Sir William Heron, held hostage by James for the surrender of his natural brother, ‘The Bastard John Heron’, considered responsible for the murder of one of James’ officials, Sir Robert Ker, the Laird of Cessford and Warden of the Scottish Middle March.

A modern representation by Ruth O’Leary of the Sacred Banner

of St Cuthbert. The original was destroyed in the Reformation: Battle of Flodden 9th September 1513

Sir William’s wife, Lady Elizabeth Heron, surrendered Ford Castle to the Scots and entered into an agreement with the Scots King that if the English would release Lord Johnstone and Alexander Hume, the Scots would not destroy Ford Castle (Lady Heron was released to enable her to seek these terms from the Earl of Surrey. Surrey agreed to the terms, but James destroyed Ford Castle nevertheless).

In the meantime, Surrey was assembling the English forces. He rode north through London with his 500 tenants and followers on 22nd July 1513, reaching Pontefract in Yorkshire on 1st August. Surrey dispatched Sir William Bulmer and Lord Dacre to the border area with their followers, to watch for the Scots incursion and wrote to the noblemen and gentlemen of England, requiring them to be prepared to attend the army with their retinues.

Surrey received the news that King James had crossed the border into England on 22nd August 1513 three days later on 25th August. On that day, Surrey wrote to all the northern gentlemen requiring them to join his army with their retinues at Newcastle on Thursday 1st September 1513.

On 30th August 1513, Surrey passed through Durham where he attended mass and received from the prior of the convent the sacred banner of St Cuthbert, considered to be a sure pledge of victory, having been carried at several previous English victories over the Scots. The banner was carried by Sir John Forster.

Thomas Howard Earl of Surrey commander of the English army at the Battle of Flodden 9th September 1513; his sons Edmund and Thomas commanded the first two divisions of the English army at the battle. Surrey was made Duke of Norfolk by King Henry VIII after the battle

Surrey was joined by his son, Sir Edmund Howard, Thomas, Lord Dacre of Gilsland with his force of border light horsemen, known as ‘Prickers’, Sir William Bulmer of Burnspeth Castle, fresh from his rout of Lord Home, Sir Marmaduke Constable and other northern noblemen.

In Surrey’s army was John Winchcombe, known as ‘Jack of Newbury’, with 100 of his employees from his cloth business.

A strong contingent joined from the north-west of England, primarily Cheshire, Lancashire and Cumberland, largely composed of longbow men.

On the next day, Surrey marched north, in such terrible weather that he feared for the safety of his son Thomas Howard, the Lord Admiral, then at sea and due to bring him 5,000 officers and men from the fleet.

Surrey conferred with Dacre, Bulmer, Sir Marmaduke Constable and others as to his future course of action and resolved to take the field on 4th September 1513. Troops were pouring in to the army from all over the north-west and north-east of England, to an extent that the army was unable to linger in Newcastle due to the lack of sufficient accommodation and advanced to Alnwick on Saturday 3rd September, where his son, the Lord Admiral, landed with his force of 5,000 experienced sea fighters.

On that day, Surrey sent a message to King James, challenging him to remain where he was in the area of Ford Castle and to meet the English army in battle the following Friday, 9th September 1513. At the same time, his son, Thomas Howard, sent an insulting message to King James saying: “As Lord High Admiral of England, I have come to justify the death of that pirate Sir Andrew Barton, of which your majesty has so often complained, and I will be in the vanguard of the English army; I expect no quarter and will give none, other than to your majesty, should you be delivered into my hands.”

King James ignored the letter from Howard, but answered Surrey saying: “to meet the English in battle is so much my wish, that had your message found me at Edinburgh, I should have relinquished all other business to meet you in the field.”

Surrey took this to mean that the Scots army would remain at Ford and meet him on the Friday, on the east side of the River Till. In fact, James’s army broke camp, crossed the Till and took up a strong position along the crest of Flodden Hill, facing south, with a marsh at one end of the hill and the Cheviot Hills at the other end.

Surrey took this as a breach of the undertaking given in James’s letter. The move presented him with the problem of how to get at the Scots without undertaking a hazardous uphill assault.

Many of the Scots nobles considered that the requirements of the treaty with France were complied with by invading England and that the Scots army should now withdraw across the border. They met in council, presided over by Lord Lindsay of the Byres.

By this time, the Scots army was being fast reduced by desertion, as soldiers left to take their booty home. Information was coming in on the increasing strength of the English army. In addition, the Scots leaders were starkly aware of the implications for their country of the defeat of an army comprising most of the nobility and prominent men of Scotland, as against a victory over an English army singularly lacking important men, most of whom were with King Henry VIII in France. There was a looming sense of foreboding in the Scottish ranks.

Following this council, Lindsay presented the view of the Scottish nobles that the army should return to Scotland. King James was transported with rage and said he would fight the English alone if necessary. He also said that if he survived the battle he would have Lindsay hanged over his own castle gate.

The elderly Earl of Angus, known as ‘Bell the Cat’ accused the Frenchman, La Motte, of encouraging the King in his rash conduct. The King replied “Angus, if you are afraid, go home.”

Angus was deeply offended and left the army. However Angus’ sons, the Master of Angus and Sir William Douglas, remained with 200 Douglas gentlemen and vassals. Both sons were killed in the battle and the Earl withdrew to a monastery, dying the following year.

Death of Sir Andrew Barton at sea in 1511; one of the grievances King James held against the English. Thomas Howard, the Lord Admiral of England, was responsible for the defeat and death of Barton: Battle of Flodden 9th September 1513

Surrey dispatched his challenge to King James from the area of Wooler, some 6 miles up the River Till from the Scots encampment. Surrey then advanced his army to within a few miles of the Scots position on Flodden Hill, from where he could see that there was no prospect of a successful assault.

Surrey sent James a further letter, complaining that his adoption of such a strong position, after Surrey’s initial challenge, was against the usage of war and that the Scots should come down off the hill to give battle. James refused even to receive the letter, presumably after being told its content.

Surrey’s army was now suffering badly from shortage of provisions. There had been little time to assemble supplies and reliance was placed on foraging. But the presence of a large Scots army ensured there was little local produce left for the English army. It is said that, on 9th September 1513, the only commodity available for the English troops was water.

Surrey’s army was joined by the Bastard John Herron, condemned as an outlaw by the Scots for the murder of the Laird of Cessford. Queen Catherine of Aragon, the wife of Henry VIII and Regent in his absence, annulled the declaration of outlawry, enabling Heron to hurry north and assist Surrey. The Heron family owned Ford Castle and Heron knew the area well, from years of banditry along the Border.

With Heron’s advice, Surrey devised a plan to march around the Scottish position on Flodden Hill by way of the east bank of the Till, make as if to invade Scotland, cross the Till near its junction with the Tweed and appear in the rear of the Flodden Hill position. It was to be hoped that the Scots would thereby be lured down from the high ground.

The English army crossed to the east bank of the River Till on Thursday 8th September 1513 and marched north along the river, to a position opposite the Scots camp on Flodden Hill, where they pitched camp.

While the English were in the area of Ford Castle, the Lord Admiral climbed the hills to the east of the castle and confirmed the presence of the Scots army along the crest of Flodden Hill. The Scottish cannon master, Borthwick, brought some of his cannon down to the river and fired at parties of English on the far bank.

On Friday 9th September 1513, the English army continued its march north along the east bank of the Till and, guided by Heron, the English cannon and Vanguard crossed the Till at the Twizel Bridge, near the junction of the Till with the Tweed. The rest of the army crossed the Till by such fords as they could find. The English army was now between the Scots and the Border.

Giles Musgrave, an Englishman in favour with King James, tried to convince the King that the English intended to invade Scotland and that he should bring his army down from Flodden Hill to the level ground, to give battle to the English. James declined to follow Musgrave’s advice.

However, James decided that he must move his army forward on to Branxton Hill, to stop that position being occupied by the English. The Scots broke camp and made the move, the cannon being trundled across the intervening valley to the new high ground. As the Scots camp was taken down, the waste was fired, smoke billowing across the field.

Once across the Till, the English army marched south down the west bank of the river towards the Scots’ position.

Thomas Howard, the Lord Admiral, and commander of one of the English divisions at the Battle of Flodden. The portrait shows Howard as the 3rd Duke of Norfolk: Battle of Flodden 9th September 1513

Robert White described the English formation: “The [English army] was separated into two bodies or wards, nearly equal in number, each having a centre and a right and left wing- the foreward being on the right, and rear or mainward on the left. The former was commanded by Lord Thomas Howard the admiral, with Henry Lord Clifford, usually called “the Shepherd Lord,” aged sixty, Richard Nevill Lord Latimer, Lord Scrope of Upsal, Sir Christopher Ward, Sir John Everingham, Sir Nicholas Appleyard, Sir William Sydney of Penshurst, Thomas Lord Conyers of Sockburn, John Lord Lumley, William Baron of Hylton, Sir William Bulmer and others, being the power of the Bishoprick under the banner of Saint Cuthbert, Robert Lord Ogle, Sir William Gascoigne the elder of Leasingcroft, Sir John Gower, and divers gentlemen of Yorkshire and Northumberland, with their tenants and followers, also the mariners brought by the admiral himself, the whole amounting to about nine thousand men. “

“Westward of the foreward, but near to it, was the extreme right wing under Sir Edmund Howard, brother to the admiral, and Marshall of the host, with whom were Sir Bryan Tunstall and one hundred men, Sir Thomas Butler of Beausy, Sir John Bothe, Sir John Lawrence of Dun, Sir Richard Bold with his vassals and archers from Lancashire, Sir Richard Cholmolndeley of Cheshire, Sir John Bigot, Sir Thomas Fitz-William, Sir Robert Warcop, the men of Hull, the king’s tenants of Hatfield, many from Lancashire and the county palatine of Chester, and two hundred men from the south of England, numbering altogether above three thousand. “

“East of the Admiral’s battalion was his left wing, under charge of Sir Marmaduke Constable of Flamburgh, who was seventy years of age, William Constable, his brother, Sir Robert, Marmaduke, and William, his sons, Sir William Percy, his son in law, with a large number of retainers of his brother Earl Percy, Sir John Constable, others from Yorkshire and Northumberland, and all their respective followers, together with one thousand men from Lancashire, almost approaching in number to those who formed the right wing. Such was the foreward, and it was considerably in advance of the other portion of the army.

“The centre of the rearward was commanded by the Earl of Surrey, in company with Sir Philip Tylney, Henry Lord Scrope of Bolton, Sir John Radcliffe of Lancashire, Sir George Dacre, Christopher Pickering, George Darcy, Sir Richard Tempest, Sir John Mandeville, Sir Christopher Clapham, William Gascoigne the younger, Bryan Stapleton, John Willoughby, John Stanley with the Bishop of Ely’s servants, Sir Lionel Percy with an hundred followers and the Abbot of Whitby’s tenants, the citizens of York and others, with their retainers, numbering, as records tell us, about five thousand men.

“Westward of Surrey, forming his right wing, though placed somewhere behind the other divisions, that assistance might be rendered when required, was Lord Dacre with fifteen hundred horse, the bowmen of Kendal wearing milkwhite coats and red crosses, and the men of Keswick, Stanmore, Alston Moor, and Gilsland, chiefly bearing large bills. In company with Dacre was the Bastard Heron, commanding another troop of horse, trained to Border depradation, and ready at any time for battle.

“On the eastern edge of the field, forming Surrey’s left wing, was a numerous division, both of horse and foot, headed by Sir Edward Stanley, a knight whose father having married the mother of Henry VII, brought him into close relationship with the king. Saving Sir William Molyneux of Seftonhall, in Cheshire, and Sir Henry Kickley, it is difficult to glean from our chronicles who were his gallant companions in arms, but his own son of the same name bore his banner, and his influence being extensive, he commanded the chief power of Cheshire and Lancashire- men well adapted for war, and exceedingly dexterous in the use of the bill and long bow.”

Robert White estimates the strength of Stanley’s division as 3,000 and Dacre’s division as something less than that figure. White puts the English army at around 26,000 and the Scots army at 20,000 to 24,000 at the time of the battle, the Scots suffering continuing desertion.

With this clear disparity in numbers and the aggressive advance of Surrey’s English army, the senior Scots noblemen urged King James not to take part in the battle, but to watch from a distance. In case matters went badly for the Scots, the King would survive to rule Scotland. They proposed that command of the Scots army be divided, so that the Earls of Huntley, Argyle and Crawford would lead the highland clans from the North, the Earl of Glencairn and Lords Graham and Maxwell would lead the men from the West and the Earls of Angus and Bothwell, with Lord Home, would lead the men from the Borders.

King James rejected this proposal out of hand and arranged his army for the coming battle.

Robert White describes the deployment of the Scots army: “They were divided into five battalions, each numbering probably from four to five thousand, the king himself heading that in the centre, whereby he was supported by two wings on every side. Four of these divisions occupied the whole front of Branxton Hill, looking to the north, and ranging in lines from west to east, with the artillery placed both before each body of men and in the open spaces between them. That which remained, forming the fifth, was placed behind the king on his right, and leaned towards the rear of that on the eastern side of the field. Farthest to the west was the extreme left wing, under Alexander Earl of Huntley and the Lord Home- the former commanding Highlanders from Aberdeenshire and other places, and the latter, being Warden of the Marches, guiding the fierce Borderers, who were inured, from boyhood, to the strife and commotion of war.“

“Next was another division from the central part of the Lowlands and from Forfarshire, north of the entrance to the Firth of Tay, under charge of John Earl of Crawford and William Earl of Montrose. The third, towards the east, being the main body, was commanded by the king himself, the principal men of the Church, and the nobility, with the gentry, many of whom fought like common soldiers, and the whole comprised the very best and bravest warriors of Scotland.”

“Eastward again, in front, was the extreme right wing of the Scottish army, strong in numbers, but consisting chiefly of undisciplined mountaineers from the west of Scotland and the Isles, led on by Matthew Earl of Lennox and Archibald Earl of Argyle.“

“The last battalion, already alluded to, consisted chiefly of yeomen and others from the Lothians, with the burghers of the larger towns on the coast, under the guidance of Hepburn Earl of Bothwell. This was a division of reserve stationed to yield help where it was requisite, but more especially to wait upon and succor the king.”

Matters began badly for the Scots on Friday 9th September 1513. It was rumoured that the man of Linlithgow, who approached the King in his chapel, appeared again in the Royal Tent overnight. It was also reported that, during the night, field mice gnawed the lining of the King’s helmet and that the King’s tent was wet from a red liquid. During a council meeting, a hare started and escaped all attempts to kill it; all incidents of ill omen (contrast with the Battle of Culloden in 1746 when a hare starting in the Government ranks was seen as a good omen).

Several of the Scottish leaders urged James to attack the English while they were crossing the River Till. Borthwick begged for permission to open fire with his cannon. James refused, saying to Borthwick that he would hang him if he fired a single shot, adding “I shall have all the enemy in the plain before me, and assay them what they can do.”

The advancing English columns crossed the Palinsburn stream and began to march across the Scottish front at Branxton Village. Edmund Howard’s men led and were followed by his brother, Thomas Howard, the Lord High Admiral. The third column comprised the men led by the Earl of Surrey himself, followed by Sir Edward Stanley’s men. Lord Dacre’s horsemen followed in the rear of Surrey’s body. Inevitably, with the difficulty of finding places to cross the Till and with such large numbers passing the river, the English army was strung out, with a substantial distance, in particular, between the Lord Admiral’s men and Surrey’s.

The Scots army formed on Branxton Hill, with Lord Home’s Borders Scots and Huntly’s Highlanders in the left hand division. On the their right, was the division commanded by Lords Errol and Crawford and the Duke of Montrose. The next and largest division was commanded by King James himself and contained the flower of Scottish nobility. The right division commanded by Lords Argyll and Lennox comprised the Highland clans. In the rear, behind the centre division, stood the troops commanded by Bothwell and the Frenchman, D’Aussi. The space between the divisions was said to be a bow’s shot.

The advancing English did not initially see the Scots on Branxton Hill. But as soon as the Lord Admiral realised that the Scots were significantly nearer than he had expected, having earlier seen them on Flodden Hill, he dispatched an urgent plea to his father to bring up the divisions forming the left wing of the English army as quickly as possible, re-enforcing the urgency of his request by sending the religious emblem he habitually wore round his neck, an “Agnus Dei”.

Battle began at 4pm, with the cannon on each side opening fire. The chronicler describes the effect: “Then out burst the ordnance with fire, flame, and hideous noise, and the master gunner of the English slew the master gunner of Scotland, and beat all his men from their guns, so that the Scottish ordnance did no harm to the Englishmen, but the Englishmen’s artillery shot into the midst of the King’s battle, and slew many persons, which seeing, the King of Scots and his brave men made the more haste to come to joining.”

The Scots army left its position on the high ground and advanced down the hill against the English.

There is perplexity as to why the Scots army gave up the advantage of the higher ground for their rash attack, which in the end lost them the battle.

There are a number of factors. It is clear from the last passage, that the English cannon fire was, at least in part, instrumental in provoking the Scots to leave their positions on Branxton Hill and attack the English army.

The armies of the period were ad hoc assemblages, put together for a particular war from a wide range of social classes and areas of the country. There was no obvious and easily understood structure of command. Local prejudices and methods of fighting will have been stronger than any army wide sense of purpose.

The first Scots formation to attack down the hill was the division commanded by Home and Huntley on the left flank and they charged against the column of Sir Edmund Howard at the head of the English advance.

Home’s Borderers and Huntly’s highlanders were particularly wild and wilful warriors, whose traditional methods of fighting were to close with the enemy and use sword, spear, bill or bludgeon. Although nominally in command, it is likely that Home and Huntley and the other nobles and gentlemen in the division were not really able to control such a large mass of excited warriors, keen to get to grips with their enemies, apparently at their mercy at the bottom of the hill. It may even be that an immediate charge was the preference of the commanders; to give them the best opportunity to despoil the enemy. Certainly, Home’s conduct during the rest of the battle does not suggest that he was particularly concerned with the fate of his King and the rest of the army.

If Sir Edmund Howard’s men followed the cannonade with discharges of arrows, the urge of Home’s men to close with them may have been even more pressing.

Howard’s men, positioned on level ground, were overwhelmed by Home’s Border men and Huntley’s highlanders and Howard’s standard taken, the English soldiers fleeing the battlefield. Howard himself was rescued by a force of English Border men led by the Bastard John Heron.

In the turmoil of their success, Home’s wild Border Scots dispersed to loot, while Huntly’s men were held in check by Lord Dacre and his ‘Prickers’, who rode up in support. Sir Bryan Tunstall, Howard’s deputy commander, was killed in this fight. Edmund Howard escaped to join his brother, the Lord Admiral.

Seeing the success of the attack by Home and Huntley, King James resolved to lead the central divisions of his army down the hill and charge the English opposite them. For this attack, the King dismounted and directed his noblemen and gentlemen to do the same. All would go into battle on the same terms, on foot.

The King’s division and the division of Erroll, Crawford and Montrose advanced down the north face of Branxton Hill, followed by the division of Bothwell and D’Aussi, leaving only Argyll’s and Lennox’s highlanders of the right flank still on Branxton Hill.

It is said that the Scots advanced in silence, “In the German manner”; that is without sounding trumpets, beating drums or cheering.

The two central divisions, comprising the majority of the Scots army, crossed the boggy moorland at the base of Branxton Hill, forded a ditch and scrambled up the slope to the columns commanded by the Lord Admiral and The Earl of Surrey.

It was here, in two hours of terrible hand to hand fighting along the muddy ditch that fronted the English line, that the battle was lost for Scotland.

The long pikes carried by many of the Scots soldiers proved a significant disadvantage. These unwieldy implements were not suitable for fighting in broken country and there had been insufficient time for the Scots to become proficient in their use. The English soldiers used their shorter bills to cut the pikes and their handlers to pieces.

King James’s decision to fight the battle on foot was intended to inspire his men. This heroic but misguided act deprived the Scots army of a hard core of mounted men and rendered the King’s party vulnerable, floundering through the mud in their heavy armour. In addition, the commanders could not exercise proper control of their troops, when on foot.

View of the Scots position from the English position before the battle: Battle of Flodden 9th September 1513

Nevertheless, the impact of the charge by the two central divisions of the Scottish army was hard for the English centre to resist. James could well have expected the division of Home and Huntley to throw itself on the right flank of Howard’s men. As it was, it was the English mounted troopers of Lord Dacre who attacked on the western flank, Home and Huntley’s men having dispersed to loot, while the commanders looked on, apparently considering that they had done all that could be required of them.

In the course of this remorseless struggle in and around the muddy ditch and bank King James of Scotland was killed, with many of his nobles, retainers and soldiers.

On the eastern flank, Sir Edward Stanley’s column arrived on the field, significantly later than the rest of the English army. Stanley immediately advanced up Branxton Hill and attacked Argyll’s and Lennox’s highlanders. Stanley’s longbow men kept up a steady barrage of arrows on the highlanders, who wore no armour. Part of Stanley’s force moved round to their left to take the Scots in the flank. The highlanders did not wait for the impact of the English charge, but fled the field, leaving Argyll and Lennox and a small party to face the English attack and perish.

With the collapse of the Scottish right, Stanley reformed his column and attacked the rear of the Scottish centre at the base of the hill. By this time, after two hours of gruelling hand to hand struggle, King James and many of his soldiers were dead.

Those Scots who could get away retreated north. They continued to fight the English as they withdrew into Scotland and several English knights were taken by the Scots during this retreat.

Lord Home appeared the following morning, but was driven away by the English, who were left in command of the field of battle, one of the classic measures of victory.

Casualties at the Battle of Flodden:

Reports of casualties at the Battle of Flodden differ widely. It may be that around 10,000 Scots were killed and perhaps as few as 1,500 English. The boggy valley floor, where much of the Scots army was trapped during the final attacks of Dacre and Stanley on the Scots flanks and rear, led to many Scots being slaughtered, as they were no longer able to defend themselves or to get away. The King’s decision to fight on foot effectively prevented any of the nobility from escaping the rout.

Survivor of the battle returns “The Blue Blanket” to the Edinburgh City Council: Battle of Flodden 9th September 1513

The effect of Flodden was to wipe out much of the current generation of Scottish nobility, from the King down. Among the Scots dead were: the Archbishop of St Andrews, the king’s natural son, the Bishops of Caithness and the Isles, the Grand Prior of the Knights of St John, the Abbot of Inchaffray, the Dean of Glasgow, 9 earls (Argyll, Bothwell, Caithness, Cassilis, Crawford, Errol, Lennox,Montrose and Rothes), 10 lords, 113 knights and a large number of family heads and clan chiefs.

It was not just the nobles who suffered. The Scottish dead were from all parts of the country and from all social levels. Edinburgh sent much of its male population to the army. They fought in the King’s division and many perished.

In the English army, from Sir Edmund Howard’s division: Sir Bryan Tunstall, Sir William Fitzwilliam, Sir John Lawrence, Sir Wynchard Harbottle and Sir William Warcop were killed: Sir Henry Grey and Sir Humphrey Lisle were captured. Otherwise few men of significance were lost.

Supporters of the Earls of Arran and Angus fighting in the streets

of Edinburgh in the “Cleansing of the Causeways” in 1515

Follow-up to the Battle of Flodden:

The result of the battle was terrible confusion in Scotland. The governing dynasty at every level and in every area of life was largely eliminated. The harvest was temporarily abandoned as Scotland gave itself up to grief.

A wave of transactions arose from the death of so many land owners. Special dispensations from feudal dues were applicable for those who had died in battle following the king, in accordance with an edict issued by King James before crossing the English border.

Queen Margaret married the Earl of Angus, to protect the succession of her young son, who became James V. A struggle ensued between the Earl of Arran and the Earl of Angus as to who should be Regent during the king’s minority, leading to fighting between their supporters in the streets of Edinburgh. Queen Margaret fled to Stirling Castle with her two young sons.

The defeat at Flodden ensured there was no significant fighting between England and Scotland for some 30 years.

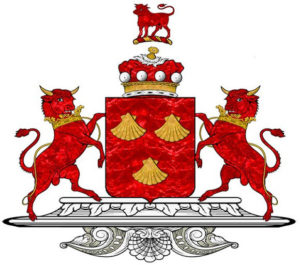

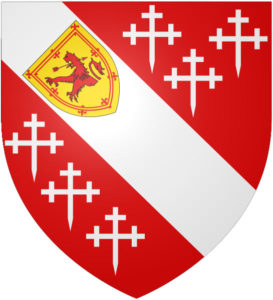

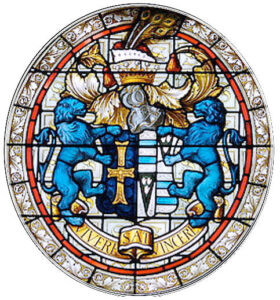

Arms of the Molyneux family. Sir William Molyneux led a party of archers at the Battle of Flodden, for which he was thanked in a letter from King Henry VIII: Battle of Flodden 9th September 1513

Anecdotes and traditions of the Battle of Flodden:

- It is said that Flodden was the victory of the English Bill over the Scots Pike. However, there is no doubt that the effectiveness of the English longbow and of the English cannon contributed significantly to the Scots defeat.

- Many of the soldiers in the central Scots divisions are reported as having removed their boots and shoes during the fighting to achieve a firmer foothold. It seems more likely that footwear was sucked off by the mud, indicating starkly the terrible conditions through which the Scots were forced to advance in the boggy area in front of Surrey’s position.

- Lord Dacre and Sir William Scot, a Scots knight and personal attendant on the King, with difficulty identified the body of King James. The King’s wounds were a deep gash down the neck, his left hand was nearly severed and he was pierced by several arrows.

- The body of King James IV was taken to London, put in a lead coffer and stored in a lumber room at Sheen Priory to the south-west of London. It was not until the time of Queen Elizabeth that the body was buried, but without a proper service.

- Legends persisted in Scotland that King James IV had not died in the battle but escaped abroad, perhaps for a pilgrimage to Palestine.

- In early 1513, Pope Leo X directed that King James IV be excommunicated for his support of the French King. Following Flodden, the Pope issued an order permitting James IV’s body to be buried in consecrated ground with full funeral rites. In spite of this, no burial was conducted. This may reflect contemporary concerns that the body was not the King’s.

- King James’ bloody surcoat was sent to the Queen, Catherine of Aragon in London. Catherine sent it on to Henry VIII in France.

- King James’ sword and a ring from his hand were passed to the College of Heralds in London, where it is still held. It may be that this was the turquoise ring sent by Anne of Brittany to encourage James to invade England.

- Sir William Molyneux is buried in St Helens Church, Sefton. His tomb commemorates his part in leading the archers of Lancashire at Flodden and refers to the letter of thanks he received from King Henry VIII.

- Sir Robert Ashton, who commanded a party of archers at Flodden, installed a window in his parish church at St Leonard’s, Middleton, now in Greater Manchester, commemorating each of the 17 archers and their chaplain.

- The ‘Archers of Ettrick’ were known in Scotland as ‘The Flowers of the Forest’. They perished nearly to a man at Flodden and the mournful tune of the same name is used at funerals in Scotland for the Dead March. Indeed it is considered a bad omen to play the tune, ‘The Flowers of the Forest’ on any other occasion.

- The Earl of Surrey knighted some 45 gentlemen from his army who had distinguished themselves in the battle, including his son Edmund Howard.

- Comment is made on the lack of activity, other than besieging border castles, by the Scots army, once it had crossed the border. The weather was terrible, with constant rain and cold. Nevertheless, the Scots were well provisioned and could have marched south to take Newcastle and then York, thereby preventing Surrey from building up such a large army. The plea from Anne of Brittany was for the Scots to enter “Three feet into England”. It may be that James felt that a short incursion over the Border was sufficient to discharge his obligation to France and to bring Henry VIII back to England.

- 11 years before the Battle of Flodden, in 1502, it was The Earl of Surrey who escorted Margaret Tudor to Scotland, to be married to King James IV. Surrey and the Scottish King were on cordial terms over a number of years. After the battle, the Earl of Surrey was restored to his family’s title of the Duke of Norfolk, with arms reflecting the victory at the Battle of Flodden.

References for the Battle of Flodden:

- British Battles by Grant

- Battles in Britain by William Seymour

- Cambridge History of the Renaissance, the Battle of Flodden by Robert White

![]() 72. Podcast on the Battle of Flodden: the defeat on 9th September 1513 at the hands of the English that annihilated a generation of Scottish aristocracy including the Scots king, King James IV: John Mackenzie’s britishbattles.com podcasts

72. Podcast on the Battle of Flodden: the defeat on 9th September 1513 at the hands of the English that annihilated a generation of Scottish aristocracy including the Scots king, King James IV: John Mackenzie’s britishbattles.com podcasts

The previous battle in the British Battles series is the Battle of Bosworth Field

The next battle in the Anglo-Scottish War is the Battle of Pinkie

To the Anglo-Scottish War Index