Clive’s victory that set the British on the path to domination of the Indian sub-continent

Mughal Infantryman: Battle of Kaveripauk on 23rd February 1752 during the Anglo-French Wars in India (Second Carnatic War)

The previous battle in the Anglo-French Wars in India is the Battle of Arni

The next battle in the Anglo-French Wars in India is the Battle of Plassey

To the Anglo-French Wars in India index

Battle: Kaveripauk or Covrepauk (now Kaveripakkam in Tamil Nadu)

War: Anglo-French Wars in India (Second Carnatic War)

Date of the Battle of Kaveripauk: 23rd February 1752

Place of the Battle of Kaveripauk: In Tamil Nadu in South East India.

Nabob of Arcot: Battle of Kaveripauk on 23rd February 1752 in the Anglo-French Wars in India (Second Carnatic War)

Combatants at the Battle of Kaveripauk: The Nabob of Arcot, Chunda Sahib, assisted by the French against Mohammed Ali, the son of the previous Nabob of Carnatica, assisted by the British.

Generals at the Battle of Kaveripauk: Raju Sahib, son of Chunda Sahib, against Captain Robert Clive.

Size of the armies at the Battle of Kaveripauk:

Clive commanded 300 European troops and 1,300 sepoys (many of them captured from the French service at the Battle of Arni), making 1,600 in all, and 6 guns.

Raju Sahib commanded 2,500 horsemen, 400 European Troops and 2,000 sepoys, making 4,900 in all, and 9 guns and 3 mortars.

Winner of the Battle of Kaveripauk: Captain Robert Clive and his British and sepoy force.

Uniforms, arms and equipment at the the Battle of Kaveripauk:

The native Indian soldiers were armed with bows, swords and spears. There were some firearms.

The Indian princes possessed field guns but they were not well handled by the Indian gunners.

The significant component of warfare in India in the 1750s became the disciplined French and British infantry and artillery. There were few of these troops, and, while effective in the field against the native levies, they were susceptible to disease and quickly became casualties.

The answer for the French and the British to the small number of European troops and their vulnerability to tropical disease was to recruit native sepoys, arm them with muskets and train them in European battle drill. This both European nations began to do.

The European troops and sepoys raised by the East India Companies of Britain and France were equipped and armed in the same way as their national infantry. The weapons carried were a musket and bayonet and small sword, known in the British army as a ‘hanger’. On campaign, each soldier carried around 25 musket rounds made up in paper cartridges in a leather pouch hung from a shoulder belt. The uniform was a coat, red for the British and blue for the French, waistcoat and tricorne hat worn according to the demands of the weather. In some instances white was worn instead of blue or red. Sepoys wore shorter coats of their employing nation’s colour. The headgear for sepoys was a local variant of the tricorne.

European troops wore stockings, gaiters and heavy shoes. Sepoys wore native clothing on their lower body with sandals or bare feet.

Contemporary accounts of the wars refer to ‘European’ troops, rather than British or French. Both British and French East India Companies recruited whatever European soldiers were prepared to join their armies regardless of nationality. If captured, a European soldier was very likely to enlist with his captor rather than remain in prison, so that the British forces contained Frenchmen along with soldiers of many other European nationalities with a predominance of British. Equally so with the French.

The presence of the various European nationalities in India was initially to trade and there was a reluctance to become involved in the raising, training and paying large bodies of troops, until it became clear that this was unavoidable if a presence was to be maintained in India. The French and British quickly became a major force in Indian warfare, particularly in the South, due to their advanced technology and discipline.

Malleson states that the rate of fire for Indian gunners in the 1750s was around 1 shot every 15 minutes. The European rate of gunfire, 2 or 3 rounds a minute, came as a shock to their opponents. Malleson states that the battle tactics of Indian commanders were based on the erroneous assumption that once European guns were discharged there was a period of 15 minutes during which an attack could be launched while the guns were reloaded. Other features of French and British tactics that came as a surprise were disciplined volley firing and the aggression of European infantry assaults. (In these early days there were no European cavalry or sepoy cavalry in India and the French and British relied on native horsemen such as the Mahrattas)

The combination of these tactical characteristics with the adept and ruthless leadership shown by Robert Clive and other British officers and by some of the French officers such as M. Paradis explains how battles were won by small numbers of European troops and sepoys fighting large native armies.

French Sepoy: Battle of Kaveripauk on 23rd February 1752 in the Anglo-French Wars in India (Second Carnatic War)

As the French and British sepoy armies became stronger the two nations ceased to fight as proxies for local rulers and the fighting between them became direct, although the wars with the native rulers continued to be the most important component in the politics of southern India, particularly as the French lost ground to the British.

A constant threat from North-West India were the Mahrattas, better disciplined mounted warriors, who in the wars of the 1750s acted as allies to the British. Later, war was conducted by the British against the Mahrattas.

The Mahratta horsemen were armed with sabres and were accompanied by an equivalent number of foot soldiers armed with swords, clubs or spears. If a horse was disabled the rider continued fighting on foot. If a rider was disabled one of the foot soldiers would take over the horse.

Background to the Battle of Kaveripauk:

The predominant power on the Indian sub-continent in the mid-18th Century was the Muslim Mogul Emperor in Delhi. The Emperor maintained a loose rule over a system of sub-rulers of varying power and loyalty. These rulers struggled over the suzerainty of a number of states of differing sizes, the contests being particularly savage when a ruler died, leaving family and retainers to fight over the succession.

The British presence in India was by way of the trading organisation, the East India Company, with no direct British Crown involvement, although Royal Troops and ships assisted in the wars. The French equivalent was also an East India Company, although there was closer involvement by the French Crown.

In the south of India the native rulers in the Deccan, Mysore, Carnatica, Tanjore and other states turned to the two competing European powers, Britain and France, for assistance. The Carnatic Wars were a protracted struggle between rival Indian claimants to the Carnatic throne, supported by the French and the British.

Between 1748 and 1751, the French Governor Dupleix worked to build up French influence in the area. The departure of Boscawen’s British fleet for England in the autumn of 1749 with the arrival of the monsoon lifted a major restraint on French ambition and the French quickly established control of the Deccan, much of the Carnatic and other states in Southern India.

In July 1751 Chunda Sahib, the Nawab of Arcot, with a force of 8,000 native and 400 French troops, advanced to lay siege to Trichinopoly, held by Mohammed Ali, the Nawab of Tanjore, an ally of the British East India Company.

The British hurried such forces as they had to assist Mohammed Ali in holding Trichinopoly. If Trichinopoly was to fall, British prestige would suffer a heavy blow and most of its troops and officers would be lost. Ensuring that Trichinopoly held out and was relieved became an essential aim for the British.

Robert Clive, a junior officer in the service of the East India Company, and one of the few officers not immured in Trichinopoly, devised a plan to divert Chunda Sahib by attacking his capital, Arcot. Robert Saunders, the East India Company governor at Madras, adopted Clive’s plan and dispatched him with a small force of British troops and sepoys for the attack on Arcot.

Clive marched to Arcot, seized the fort in the city and held it against a force sent by Chunda Sahib and commanded by his son, Raju Sahib. See the Siege of Arcot.

After Clive’s successful defence of Arcot Raju Sahib retreated precipitately to Vellore and then south to the River Poondi, where he was resoundingly beaten again by Clive at the Battle of Arni.

Following the Battle of Arni Clive captured the fortified pagoda at Conjeveram, destroyed it and marched to Fort St David on the coast to the south of Pondicherry to prepare for the relief of Trichinopoly.

The fate of Trichinopoly was now essential for each side. Chunda Sahib, the Nawab of Arcot, and the French who besieged the city needed to take Trichinopoly to secure their hold on Tanjore and the city state of Arcot.

Mohammed Ali, the Nawab of Tanjore, needed to retain his capital if he was to stay in power and the British needed to ensure the safety of the city to maintain their newly established credibility as a power in Southern India.

Emperor Aurangzeb accompanied by Indian troops: Battle of Kaveripauk on 23rd February 1752 in the Anglo-French Wars in India (Second Carnatic War)

Once Clive was out of the field at Fort St David the French Governor Dupleix and Chunda Sahib took steps to divert him from relieving Trichinopoly. Chunda Sahib’s son, Raju Sahib, the loser at Arcot and Arni, assembled his scattered troops and marched to the town of Conjeveram. The pagoda at Conjeveram was repaired and garrisoned and Raju Sahib moved on to Vendalur, perilously close to the British base at Madras. During February 1752, Raju Sahib’s troops ravaged the area, burning the country houses of several of the British East India Company’s senior administrators.

The result was exactly as Dupleix and Chunda Sahib planned. Clive was abruptly ordered to abandon the preparations to relieve Trichinopoly, to return to Madras and defend the city.

Clive assembled a force of European troops and sepoys from the small garrison left at Madras, with troops from Bengal and part of the Arcot garrison, that he summoned to Madras.

On 22nd February 1752 Clive marched out of Madras with 300 European troops, 1,300 sepoys (many of them originally French sepoys, captured at Arni) and 6 guns, making for Vendalur where Raju Sahib and his army were last known to be.

Raju Sahib’s intelligence system kept him fully informed of proceedings at Madras. Clive’s intelligence seems to have been good, but not as good as Raju Sahib’s.

Clive reached Vendalur at 3pm on 22nd February 1752, to find that Raju Sahib’s army was gone, marching in dispersed groups and making for Kanchipuram, further west.

Clive reached Kanchipuram at 4am on 23rd February. Raju Sahib’s army again was gone. Clive was informed that Raju Sahib was heading for Arcot, with the intention of storming the fort.

Clive’s troops were now too exhausted to march further for the time being and a halt was called at Kanchipuram. The opportunity was taken to force the surrender of the fortified pagoda in the town.

Raju Sahib had marched for Arcot and intended to take the fort by means of treachery, two of the fort’s sepoy officers being in his pay and suborned to open the gate on a signal. When the arranged signal was made there was no response and it was clear that the plot to give up the fort had been foiled.

Raju Sahib immediately turned back to attack Clive’s force and marched to Kaveripauk, a town through which Clive’s troops would soon pass on their route west to Arcot.

In the course of these journeys, Raju Sahib’s men marched 58 miles in 30 hours.

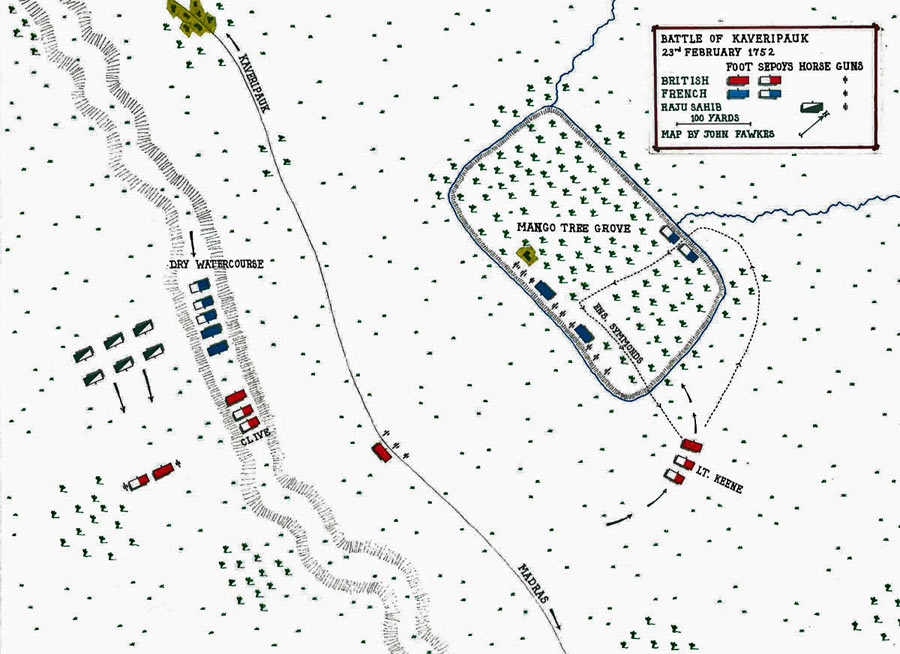

Map of the Battle of Kaveripauk on 23rd February 1752 in the Anglo-French Wars in India (Second Carnatic War): map by John Fawkes

Account of the Battle of Kaveripauk:

At sunset on 23rd February 1752 Clive’s troops approached the town of Kaveripauk, visible in the distance. As they marched in open formation down the road 9 French guns opened fire on them. Clive had marched into an ambush.

These French guns were positioned behind a ditch and a bank 250 yards to the right of the road on the edge of a dense mango tree plantation.

On the left side of the road, running parallel to it was a dry watercourse.

Raju Sahib’s force was positioned with some of his European troops and his guns in the mango tree plantation. The rest of his infantry were further up the road towards Kaveripauk with his mounted troops on the far side of the watercourse behind the infantry.

Clive quickly gave his directions. The baggage was sent to the rear with one of the guns and a platoon of infantry for protection. 2 more guns with a platoon of Europeans and 200 sepoys were positioned beyond the dry watercourse to keep Raju Sahib’s horsemen at bay. The remaining 3 guns stayed on the road to fight it out with the French guns in the mango grove, supported by 2 platoons of European infantry. The rest of the force took cover in the dry watercourse.

Raju Sahib’s French infantry entered the watercourse and advanced down it in files of 6, exchanging fire with Clive’s infantry further along.

The firing across the battlefield continued for two hours into the night, lit by the moonlight.

During this time Raju Sahib’s cavalry attempted to attack the 2 guns and infantry opposed to them and to take the baggage, but were repulsed.

The French guns, firing from the mango grove, were getting the better of the 3 British guns that were exposed on the road. Many of the gunners and supporting infantry became casualties.

By 10pm it was clear that Clive would have to retreat unless the French guns could be subdued. Ever aggressive, Clive resolved to attack the guns.

Clive sent a sepoy sergeant called Shawlum, who was a local man, to reconnoitre the far side of the mango grove with a small party of sepoys. Shawlum returned from his reconnaissance to say that there appeared to be no troops guarding the rear of the mango grove. This proved to be incorrect.

Yogini Goddess from Kaveripauk: Battle of Kaveripauk on 23rd February 1752 in the Anglo-French Wars in India (Second Carnatic War)

Clive assembled a force of 200 Europeans and 400 sepoy, from the troops in the watercourse and was guided by Shawlum to the rear of the mango grove. Clive’s force was half way to its destination when word came that with his departure the troops remaining in the watercourse had ceased firing and were on the verge of flight.

Clive left Lieutenant Keene to command the party heading for the back of the mango grove and returned to the watercourse where, with some difficulty, he restored the position and firing resumed.

Keene halted the assaulting party 300 yards from the mango grove and sent Ensign Symmonds on to carry out a final reconnaissance.

In the dark, Symmonds stumbled on a trench occupied by a force of French sepoys. Symmonds was challenged but answered in French and persuaded the sepoys that he was a French officer. Symmonds carried on and found himself behind the French gun line, supported by 100 French troops but with no sentries or observation to the rear.

Symmonds returned to the main party, taking care to avoid the area of trench occupied by the French sepoys and led Keene’s party up to the French gun positions.

Clive at the Battle of Kaveripauk on 23rd February 1752 in the Anglo-French Wars in India (Second Carnatic War)

The British troops fired a volley into the French gunners and infantry at 30 yards, causing the French immediately to flee without returning a shot.

Many of the French took refuge in a ‘choultry’ or lodging house in the grove. The British troops surrounded the choultry and summoned the French to surrender, which they did, the French soldiers coming out one by one and surrendering their weapons.

Indian Sepoy: Battle of Kaveripauk on 23rd February 1752 in the Anglo-French Wars in India (Second Carnatic War)

The sudden silence from the French battery showed Clive and his troops in the watercourse that the attack had succeeded. The French further up the watercourse found out what had happened when fugitives arrived from the battery. They promptly fled and their cavalry dispersed.

Clive’s force spent the rest of the night on the battlefield, gathering in and caring for the wounded. In the morning they found they had captured 9 guns, 3 coehorn mortars and 60 European troops.

Casualties at the Battle of Kaveripauk:

Raju Sahib’s force suffered 50 Europeans and 300 sepoys killed, with many more wounded. The British suffered 40 Europeans and 30 sepoys killed, with, many more wounded.

Battle Honour and Campaign Medal:

There is no Battle Honour or Campaign Medal for the Battle of Kaveripauk.

Follow-up to the Battle of Kaveripauk:

Casualties were heavy in the battle due to the prolonged period of artillery bombardment and the lack of cover for the party on the road. Making arrangements for the wounded of each army delayed a pursuit. During the morning following the battle Clive sent a message to the governor of the fort at Kavrepauk requiring him to surrender. The governor replied that he was not in a position to comply as there was a large number of fugitives from Raju Sahib’s army taking refuge in the fort outnumbering his own troops.

Clive sent a detachment to attack the fort but before they arrived the fugitives troops left and the governor surrendered.

Clive marched on to Arcot from where he proposed to advance on Vellore to capture the elephants used in the attack on Arcot with the baggage and weapons that Raju Sahib had deposited there.

Before he could undertake this march Clive received instructions to take his troops to Fort St David and press on with the operation to relieve Trichinopoly.

Regimental anecdotes and traditions from the Battle of Kaveripauk:

- Malleson includes Kavrepauk in his book ‘The Decisive Battles of India 1746-1859’ on the basis that it was this victory by Clive that convinced the native potentates that the British were a serious military power. For Malleson, following Kavrepauk, the British did not look back and British rule became the destiny for India. Malleson wrote his book in 1885. It is clear that for him any idea that India might cease to be ruled by Britain was unthinkable.

References for the Battle of Kaveripauk:

- Military Transactions by Orme

- The East India Military Calendar Volume II

- The Decisive Battles in India by Malleson

- History of the British Army by Fortescue Volume II

The previous battle in the Anglo-French Wars in India is the Battle of Arni

The next battle in the Anglo-French Wars in India is the Battle of Plassey

To the Anglo-French Wars in India index