Sir Robert Napier’s capture, on 13th April 1868, of the Fortress of Magdala, stronghold of the Emperor Theodore III of Abyssinia

The previous battle in the British Battles series is the Siege of Delhi

The next battle in the British Battles series is the Battle of Ali Masjid

Battle: Magdala

War: Abyssinian War

Date of the Battle of Magdala: 13th April 1868

Place of the Battle of Magdala: In Abyssinia, modern Ethiopia, to the east of the present capital, Addis Ababa.

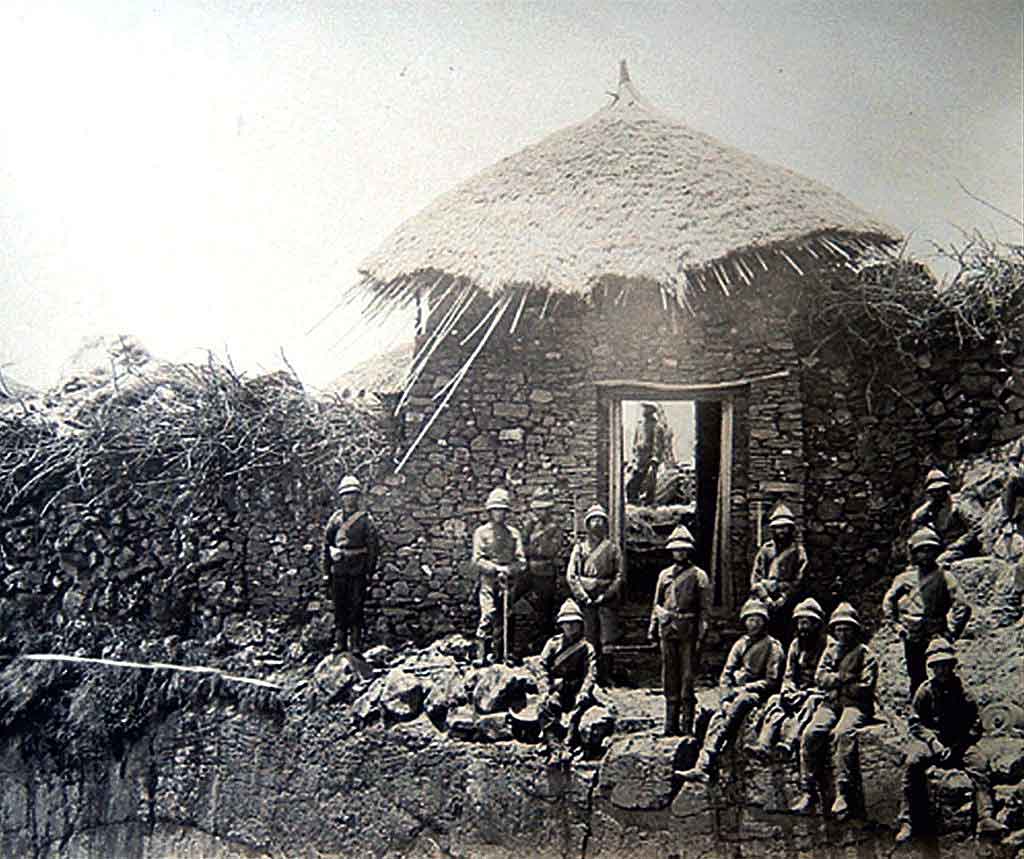

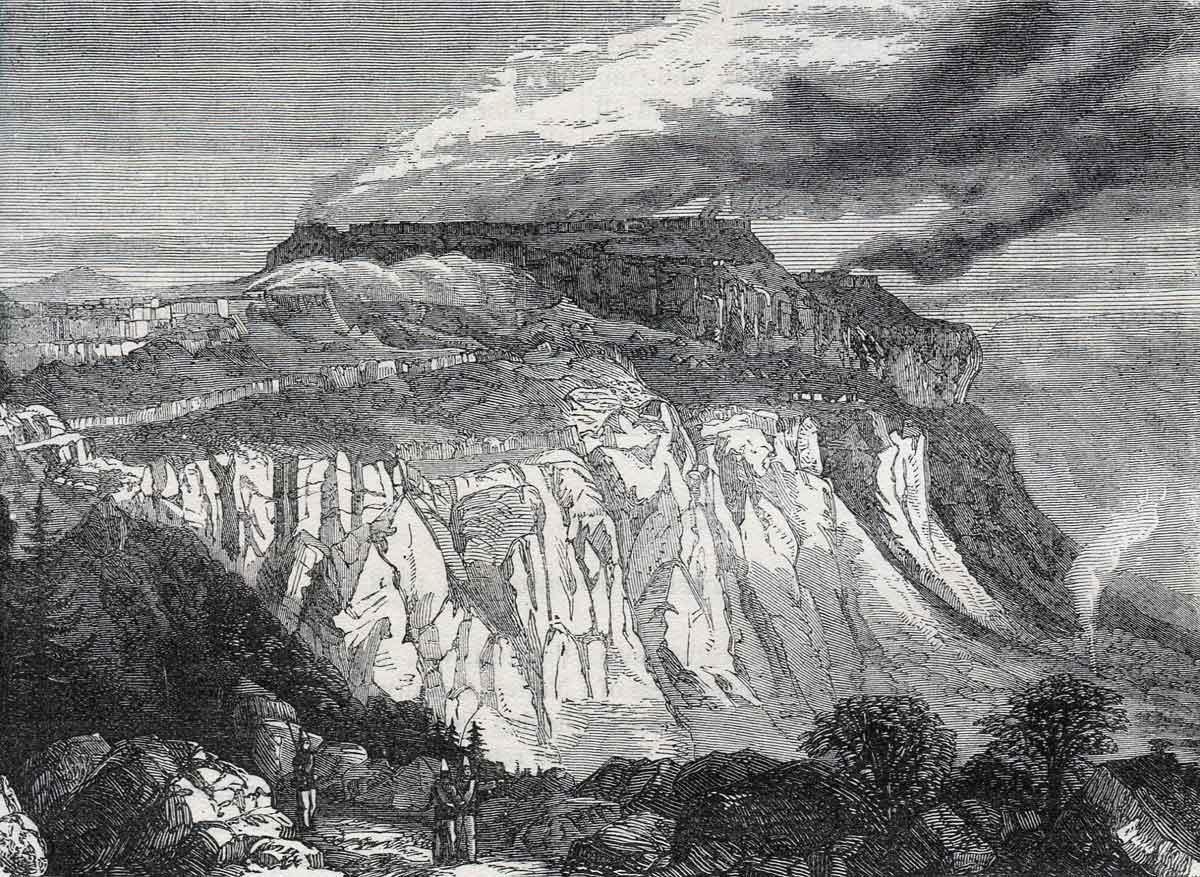

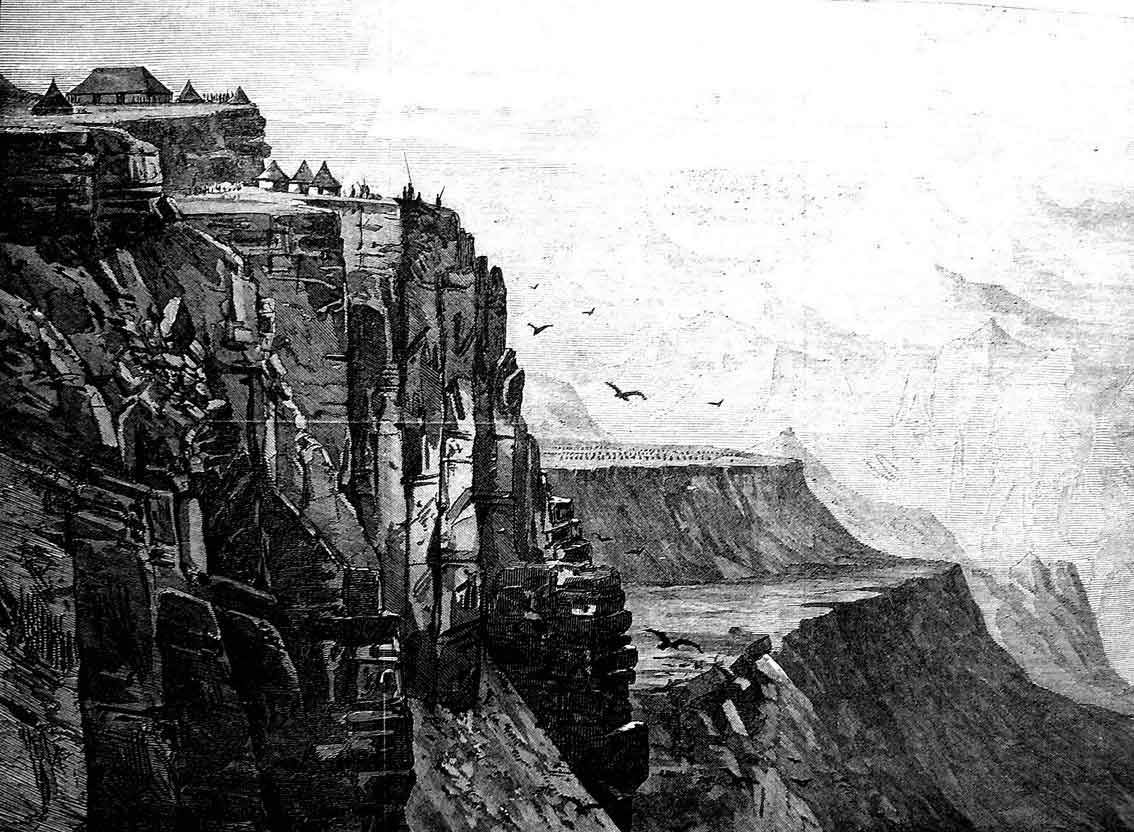

Storming the palace fortress of Magdala at the Battle of Magdala on 13th April 1868 in the Abyssinian War

Combatants at the Battle of Magdala: British and Indian troops against the army of the Emperor Theodore III of Abyssinia.

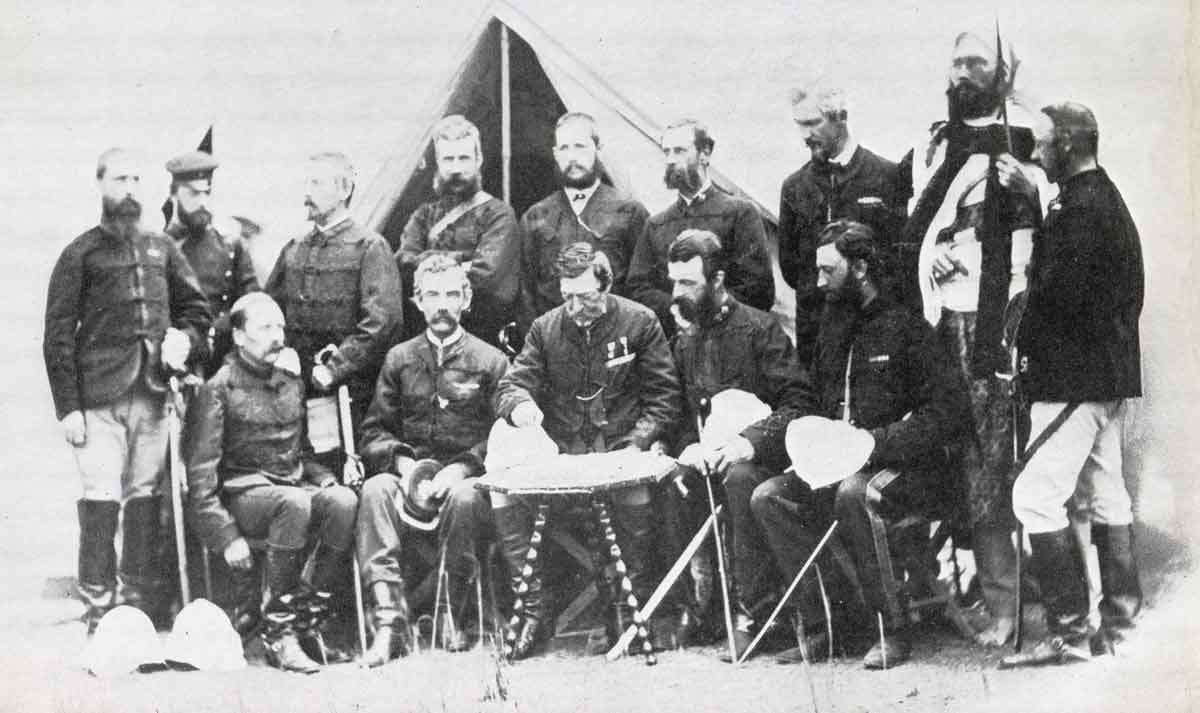

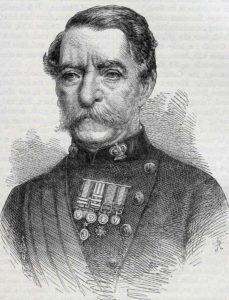

Sir Robert Napier, British commander at the Battle of Magdala on 13th April 1868 in the Abyssinian War

Commanders at the Battle of Magdala: Lieutenant General Sir Robert Napier, the general officer commanding the Bombay Army against the Emperor Theodore III of Abyssinia.

Size of the armies at the Battle of Magdala: The British force comprised 13,000 soldiers (2,674 British) from the British and Indian regiments of the Bombay, Bengal and Madras Armies, assisted by 3,000 men of the Bombay and Bengal Coolie Corps.

Emperor Theodore III of Abyssinia commanded a changing army, which at its largest probably comprised some 30,000 men.

Winner of the Battle of Magdala: The British and Indian army

Uniforms, arms and equipment at the Battle of Magdala: The British army was undergoing rapid change following the Crimean War and the Indian Mutiny. British regiments were equipped with new Snider-Enfield single shot breech loading rifles, delivered specifically for the Abyssinian Campaign. The Indian infantry regiments still carried smooth bore muskets.

In the aftermath of the Indian Mutiny, the British authorities chose not to equip Indian regiments with more modern firearms.

The Royal Artillery were equipped with modern Armstrong field guns.

The Abyssinians were armed with a wide variety of ancient and modern firearms, swords, spears and shields. They possessed a number of modern artillery pieces, overseen by German technicians, although apparently reluctantly.

3rd Dragoon Guards, officer in Home Service uniform: Battle of Magdala on 13th April 1868 in the Abyssinian War

British and Indian Regiments in the Abyssinian Expeditionary Force:

3rd Dragoon Guards, now the Royal Scots Dragoon Guards

10th Bengal Native Cavalry

12th Bengal Native Cavalry

3rd Bombay Native Cavalry

3rd Sind Horse

Royal Naval Rocket Batteries

Royal Artillery

Royal Engineers

Bombay Sappers and Miners

Madras Sappers and Miners

4th King’s Own Royal Regiment at the Battle of Magdala on 13th April 1868 in the Abyssinian War: picture by Richard Simkin

1st Battalion 4th King’s Own Royal Regiment, now the Duke of Lancaster’s Regiment

26th Foot, the Cameronians, now disbanded

33rd Foot, later the Duke of Wellington’s Regiment and now the Yorkshire Regiment

45th Foot, later the Sherwood Foresters and now the Mercian Regiment

21st Punjabi Bengal Native Infantry

23rd Punjabi Bengal Native Infantry

2nd Bombay Native Infantry (Grenadiers)

3rd Bombay Native Infantry

5th Bombay Native Infantry (Light Infantry)

8th Bombay Native Infantry

10th Bombay Native Infantry

18th Bombay Native Infantry

25th Bombay Native Infantry (Light Infantry)

27th Bombay Native Infantry (1st Baluchis)

27th Bombay Native Light Infantry in Abyssinia: Battle of Magdala on 13th April 1868 in the Abyssinian War

Background to the Battle of Magdala: The crisis between Britain and Abyssinia in 1867 arose from the character of Emperor Theodore III of Abyssinia.

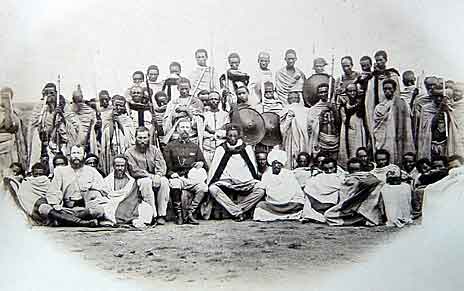

David Chandler described the Abyssinian ruler in these terms: ‘The Emperor Theodore was a most complex personality. He was a combination of robber-chief, idealist and madman. Periods of great courtesy and generosity frequently gave place to fits of insensate rage. Deep religious (Christian) convictions contrasted with a complete disregard for human life and suffering. In his last years his moods varied inconsistently and unpredictably from hour to hour, but at no time did his personal courage desert him.’

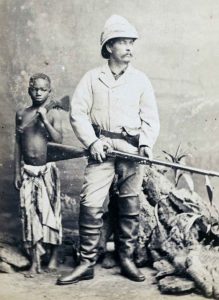

Emperor Theodore III of Abyssinia with his entourage: Battle of Magdala on 13th April 1868 in the Abyssinian War

Rising as a provincial governor, Theodore was crowned Emperor in 1855. Magdala, captured from the Gallas, became his mountain-fortress.

In 1862, the British Government sent Captain Charles Cameron as consul to the Abyssinian Court.

The Emperor wrote to Queen Victoria with various requests. Unfortunately, the Foreign Office in London overlooked the letter and no reply was sent. This discourtesy played on Theodore’s mind.

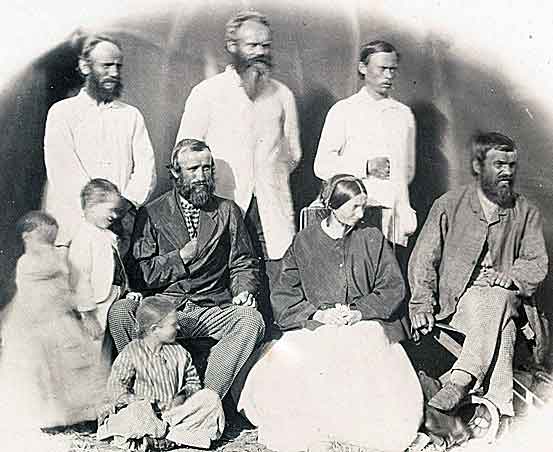

In 1864, convinced of British hostility, Theodore detained Captain Cameron and a number of European missionaries and traders and their families.

European prisoners of the Emperor Theodore III: Battle of Magdala on 13th April 1868 in the Abyssinian War

Negotiations took place in attempt to secure the release of the captives and at times it seemed as if Theodore would release them.

In around December 1866, the captives were moved to the palace fortress of Magdala and it became clear that they would not be freed.

A number of British domestic crises were resolved in 1866-7, leaving the British Government free to turn its mind to resolving the issue of the captives in Abyssinia, urged on by increasing public concern.

The main obstacle to action was the lack of knowledge of Abyssinia and its remoteness. The Suez Canal was not completed until 1869 requiring any force sent from Britain to journey around the southern tip of Africa.

The nearest substantial British garrison was the Bombay Army on the west coast of India. It was resolved that an expeditionary force would be sent from Bombay.

The planning and command of the expedition to Abyssinia was conferred on Lieutenant General Sir Robert Napier, the Commander in Chief of the Bombay Army.

Napier exercised his considerable administrative and military experience in organising the expedition to release the captives in Abyssinia.

In particular Napier insisted that a lightening raid by a small force was impractical and that a fully organised expedition was the only solution, in spite of it’s the cost, which Napier warned would be substantial.

Loading elephants in Bombay on board ship for use in Abyssinia: Battle of Magdala on 13th April 1868 in the Abyssinian War

A reconnaissance to the Red Sea shore of Abyssinia identified Annesley Bay as the most appropriate place to land the expeditionary force. There were no existing port or transport facilities available.

Napier’s force was confronted with the task of building jetties, camps, storage facilities, a railway line, communications and a water supply.

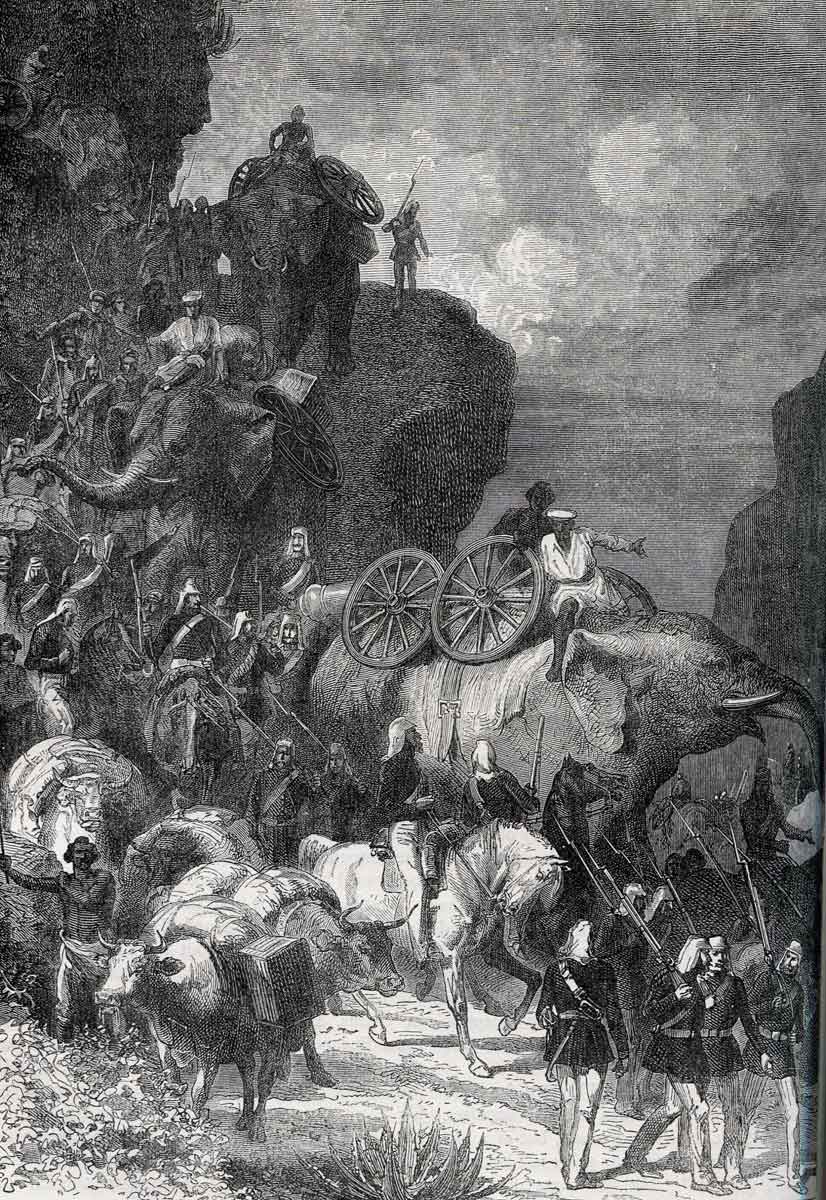

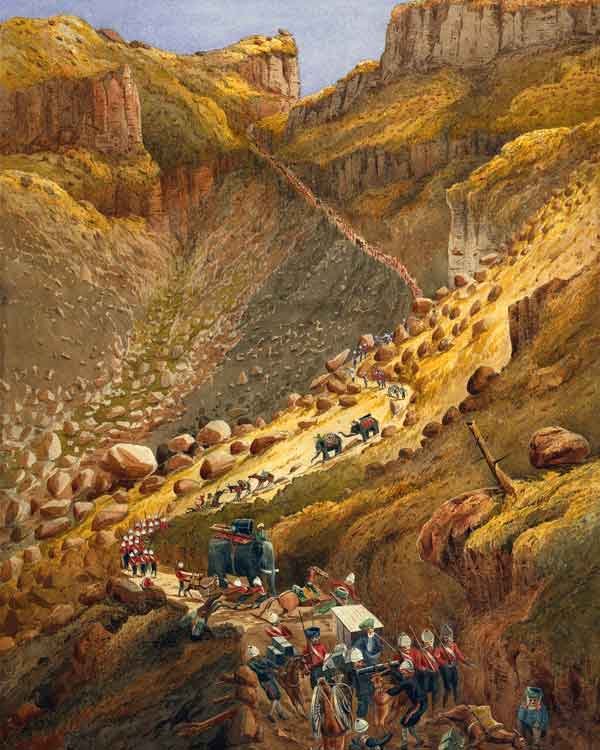

Some 35,000 baggage animals, mules, donkeys, camels, horses and elephants were acquired from a number of countries and transported to Annesley Bay.

241 ships were used to bring in supplies and the troops.

The advance guard of the expedition arrived in Annesley Bay on 21st October 1867. Sappers began construction of the camps around the village of Zula, roads to the port area and inland and a tramway.

Work was begun on the surveying and construction of a railway to carry troops and supplies inland.

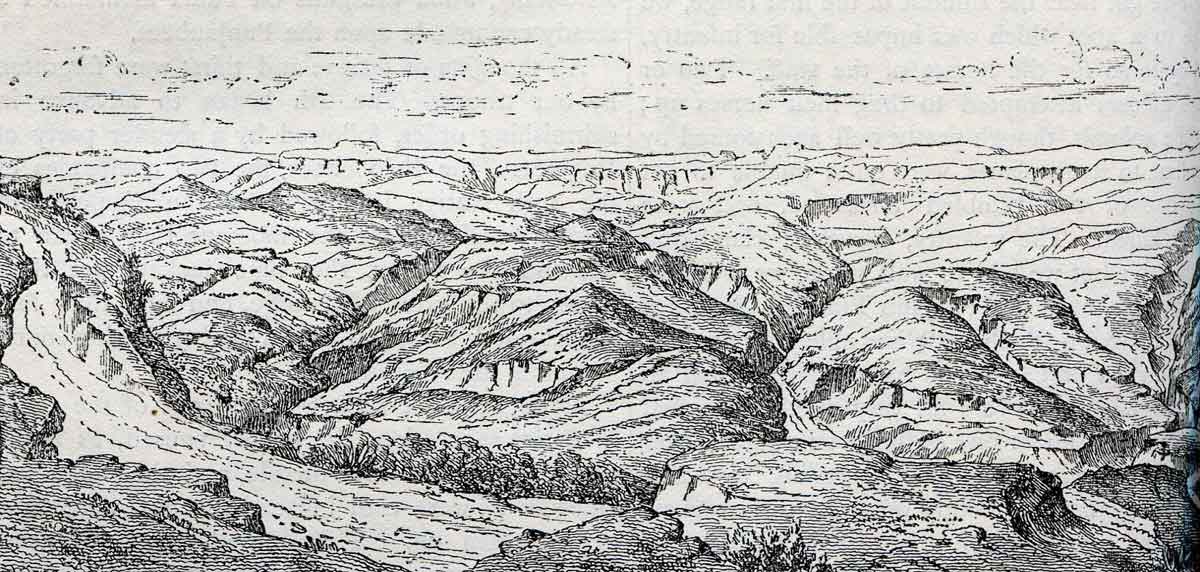

Napier’s army faced a lengthy march across the lowlands lying inland from the sea and then a long and difficult trek through the hills and mountains to the fortress of Magdala, which lay in the centre of Abyssinia.

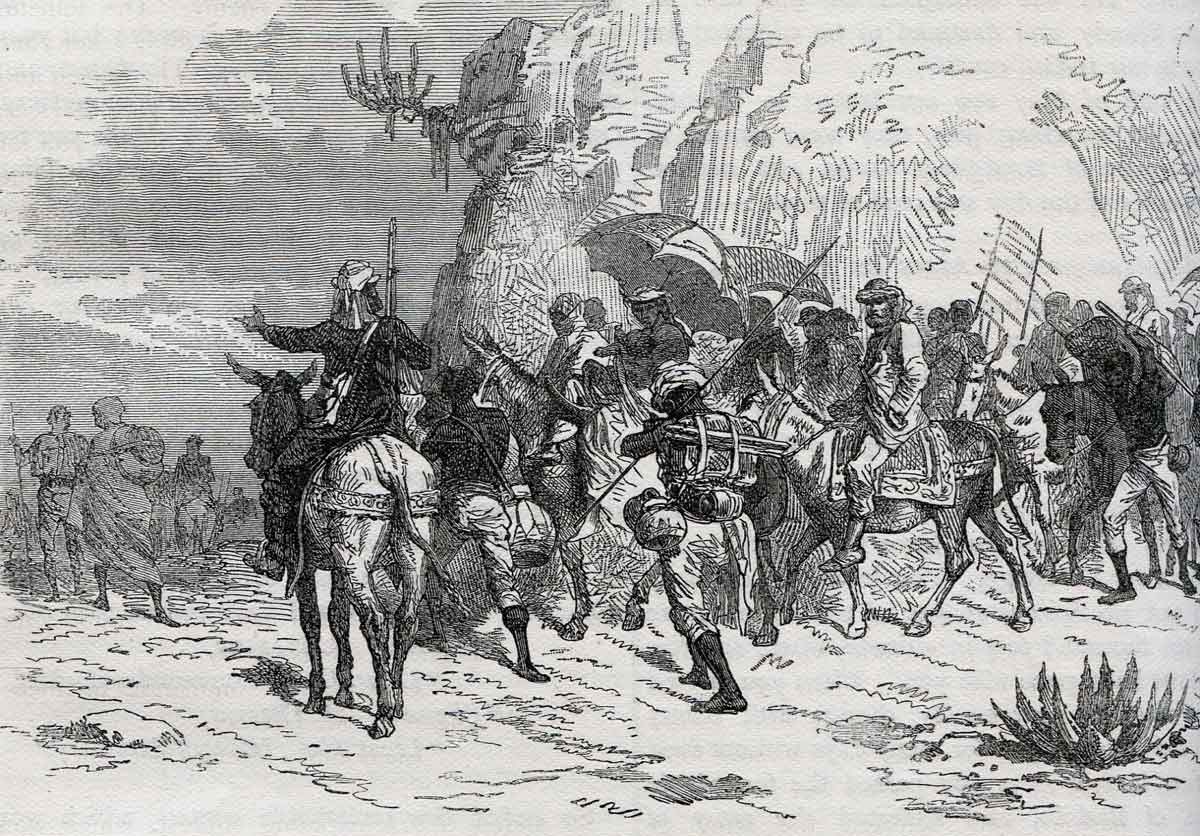

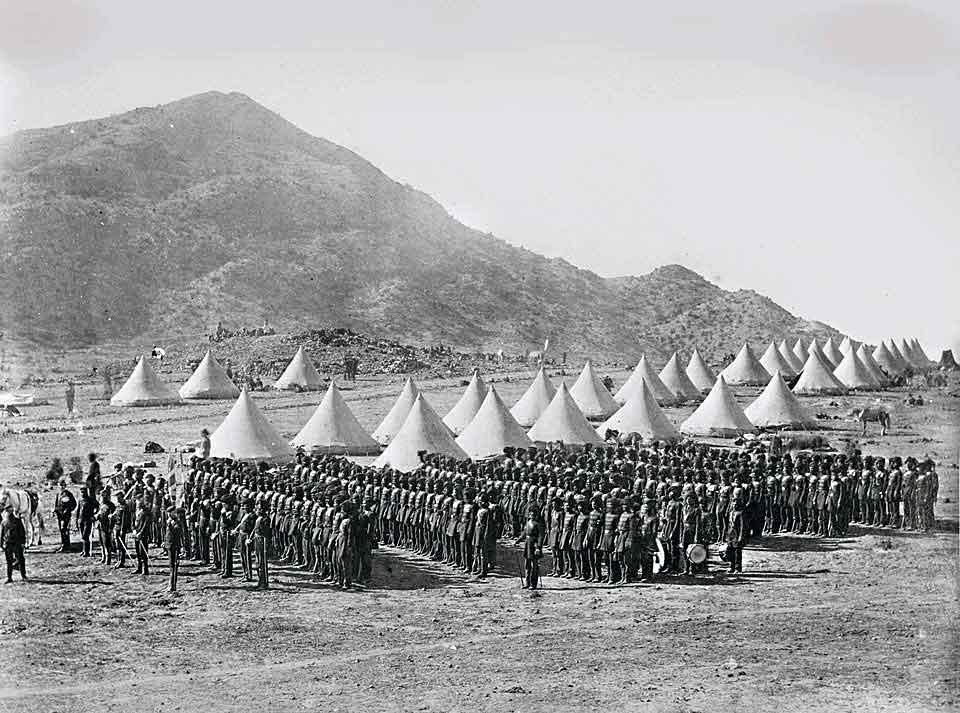

British and Indian Army on the march in Abyssinia: Battle of Magdala on 13th April 1868 in the Abyssinian War

Sir Robert Napier arrived on HMS Ocean in Annersley Bay on 2nd January 1868.

By this time, many of the troops, supply animals and supplies were ashore and accommodated around Zula.

A reconnaissance party was already in the mountains, making contact with local rulers, several of whom could be relied upon to assist against the Emperor Theodore.

British shipping in Annesley Bay in 1867: Battle of Magdala on 13th April 1868 in the Abyssinian War

A report, dated 18th December 1867, reached Napier from the interior reporting that the Emperor was moving from Debra Tabor to Magdala with a force of 8,000 warriors, 6 guns and a wagon column of ammunition.

Napier decided to march with his main force and attempt to cover the 400 miles from Zula to Magdala in time to forestall the Emperor Theodore.

The British Government was urging Napier to conduct a ‘rapid dash’ with a small force.

Napier was convinced that a methodical advance by a substantial army, leaving garrisons along the route, was the only safe way of proceeding.

Elephants transporting guns in Abyssinia: Battle of Magdala on 13th April 1868 in the Abyssinian War

A striking force of 5,000 men, formed as the First Division and commanded by Sir Charles Staveley, Napier’s deputy, set off for the interior on 25th January 1868.

The remaining troops, forming the Second Division, provided the garrisons for the lines of communication.

The advanced brigade reached Adigrat on 29th January 1868, the troops finding it a relief to leave the humid coastal region for the cooler mountains. Nevertheless, the going was arduous in the extreme.

Although the army marched from dawn to dusk, the distance covered in a day seldom exceeded 10 miles.

Account of the Battle of Magdala:

The advance brigade reached Antalo on 14th February 1868, having travelled 200 miles from the base at Zula.

An extended halt was called at Antalo, as the various formations marched in and Napier re-organised the army’s baggage arrangement.

From this point, no wagon could be used and all supplies and baggage would be carried by the draught animals.

In view of the extreme difficulty of making progress through the roadless mountains, the baggage allowance was reduced several times.

While at Antalo, Napier received news that Emperor Theodore had reached Magdala with his army and artillery, which included the emperor’s pride and joy, a 70-ton mortar named Theodorus.

It was clear that Napier needed to make the ‘final dash’ for Magdala, urged on him by the London and Indian governments for months, the concern being that Theodore would remove his captives to a more remote location.

The Emperor Theodore was in a perilous position. His fortress of Magdala was in effect under siege, thousands of hostile Gallas tribesmen blockading him to the south, with Napier advancing on him from the north.

3rd Dragoon Guards in Abyssinia: Battle of Magdala on 13th April 1868 in the Abyssinian War: picture by Orlando Norie

At the beginning of April 1868, Napier sent a message to the Emperor Theodore, requiring him to surrender. There was no reply.

On 9th April 1868, the Emperor Theodore watched from the top of Mount Fahla the approach of the distant columns of Napier’s army.

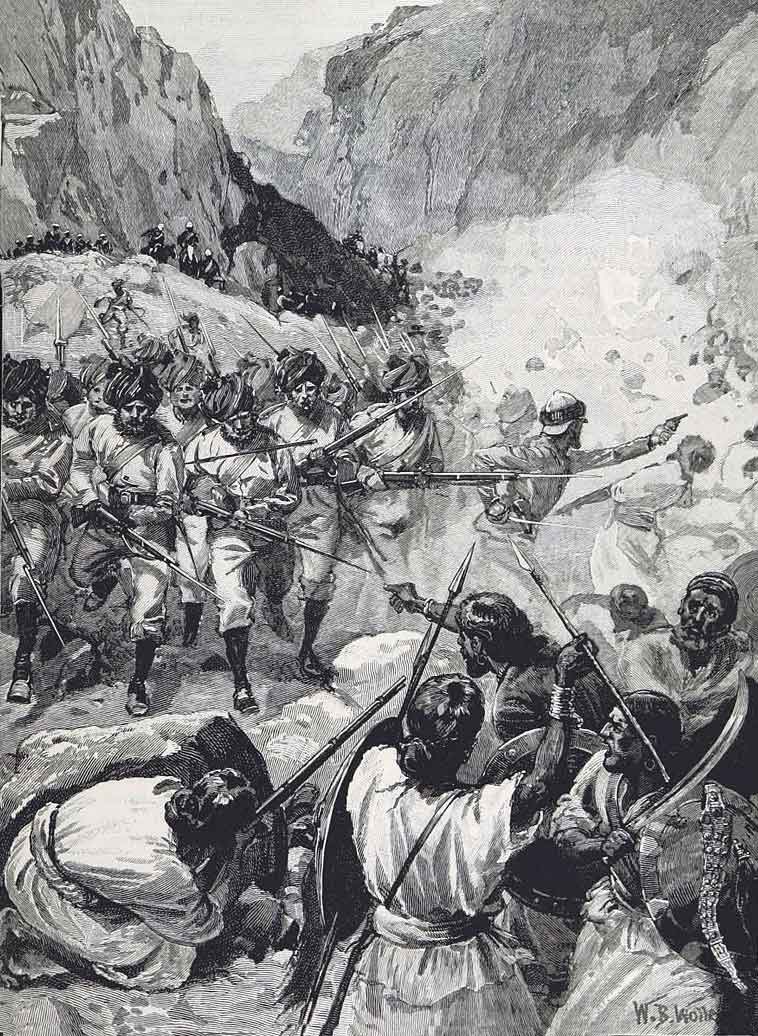

23rd Punjab Pioneers attack with the bayonet: Battle of Magdala on 13th April 1868 in the Abyssinian War: picture by William Barnes Wollen

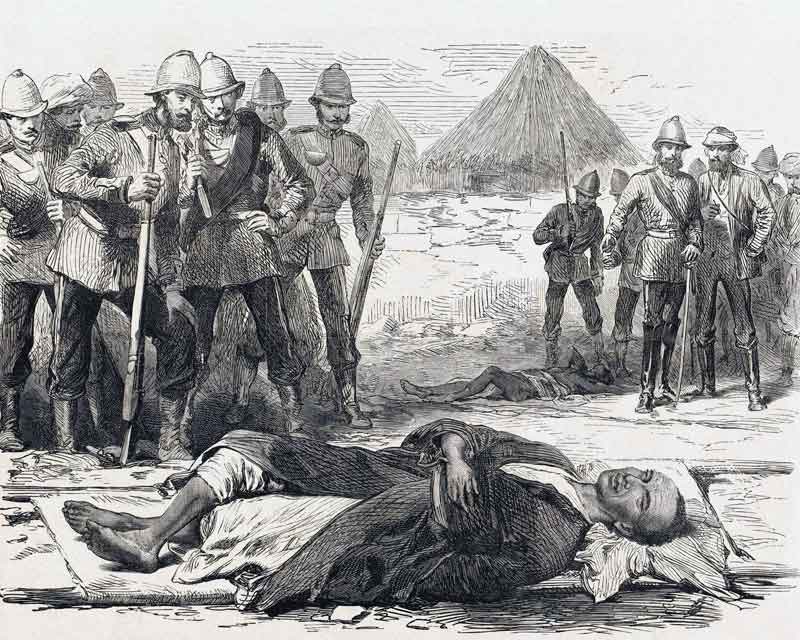

That night, in a blind rage, it is reported that Theodore executed several hundred Abyssinian prisoners, mainly Gallas, throwing them from the top of the cliff, manacled in pairs.

By the next morning, Theodore recovered his composure and marched out of Magdala with his army, now of around 30,000 men, to oppose the invaders from Mount Fahla, where his 7 guns and ‘Theodorus’ were in place.

On 10th April 1868, Napier’s troops moved down to the Bashilo River.

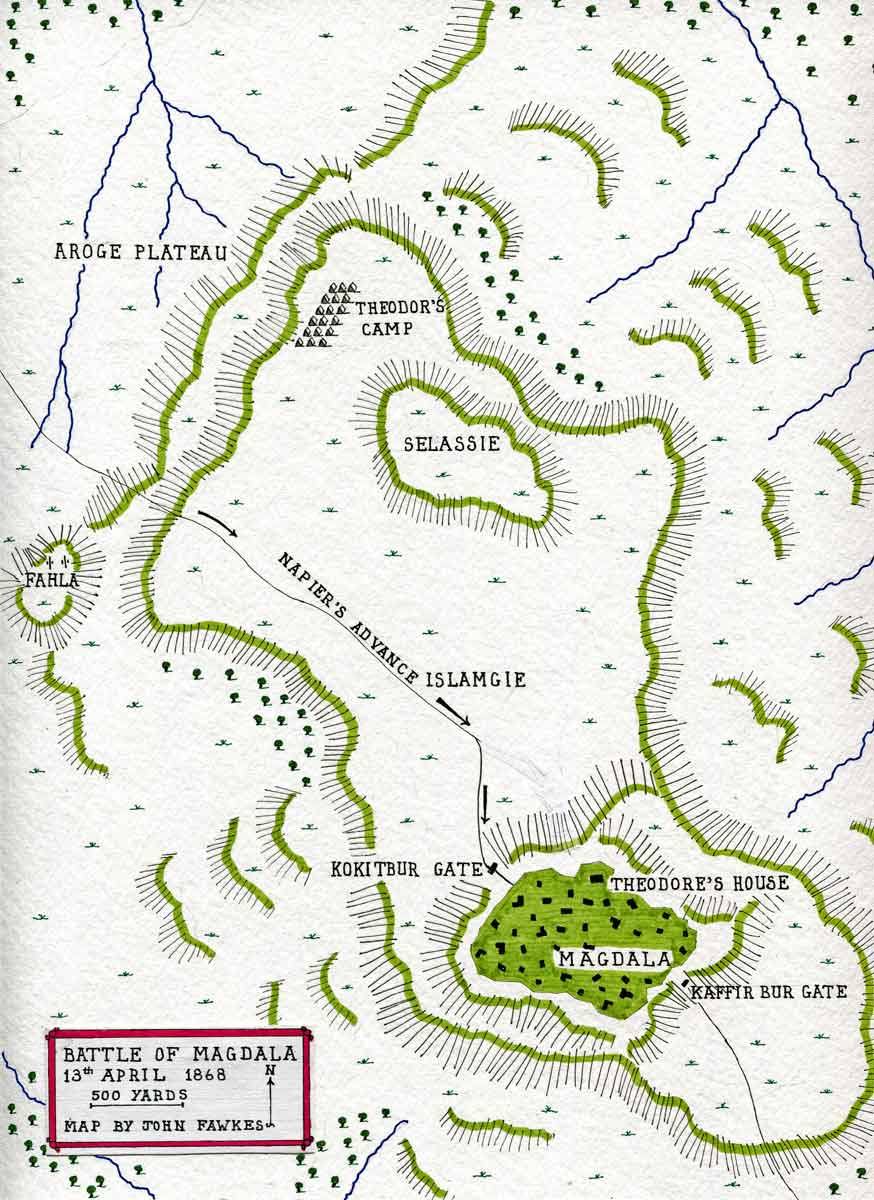

From there, Napier moved units up to occupy the point where the King’s Road from the north-east emerged from the Aroge ravine onto the Aroge plateau before Mount Fahla.

Other sections of the Second and First Brigades moved onto the Aroge plateau, beyond which lay the crescent of three mountains forming the Magdala chain, Fahla at the western end, Selasse in the middle and Magdala itself at the eastern end.

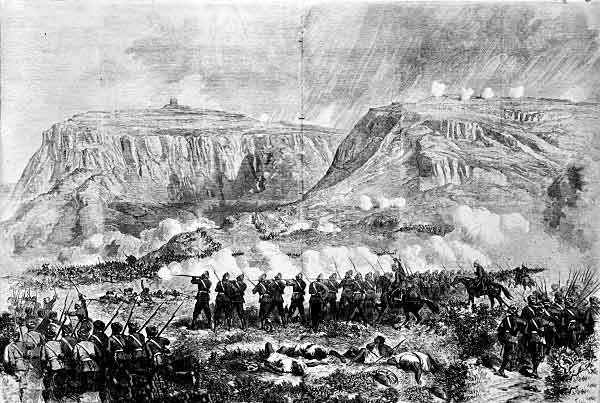

British and Indian troops in action at the Battle of Magdala on 13th April 1868 in the Abyssinian War

From his position on Fahla, at about 4pm, Theodore launched an assault across the Aroge plateau of 6,000 men, led by his favorite chief, Fitaurari Gabi and opened fire with his guns.

While the first round landed close to Napier and the British troops, thereafter the Abyssinians gunners lost the range and ceased to present a threat.

The 70-ton mortar, Theodorus, blew up on its first discharge.

Confused fighting developed across the Aroge plateau.

An Abyssinian attack on British guns positioned above the Aroge defile and defended by 2 companies of the King’s Own Regiment was driven off with considerable loss.

Elsewhere on the plateau the British and Indian regiments advanced and the Abyssinians fell back.

The British First and Second Brigades bivouacked at the entrance to the Aroge valley.

The Emperor Theodore was in despair. At midnight he sent a message to one of captives, Mr. Rassam, saying: ‘I thought that the people coming are women; I find that they are men. I have been conquered by the advanced guard alone. All my gunners are dead; reconcile me with your people.’

By dawn the British troops were advancing, when they met a flag of truce. By the evening the captives held by Theodore were released and in the British camp, but Theodore baulked at Napier’s demand for his unconditional surrender.

The British and Indian cavalry circled round Magdala Mountain to prevent Theodore’s escape, while the infantry and guns moved onto Mount Selasse, where some 20,000 Abyssinian troops surrendered.

Theodore withdrew into his palace fortress of Magdala.

Magdala itself rose, with steep cliff sides, some 300 feet above the central Islamgie plain. The top of Magdala was covered by the huts and houses of the palace compound.

Entrance to Magdala from the north was by way of a walled gate, the Kukitber Gate.

On 13th April 1868, a storming party from the 33rd Regiment, supported by Bengal and Bombay Sappers and Miners advanced on the gate.

Soldiers of the 33rd scaled the wall and forced the gate. The Abyssinian troops in Magdala thereupon surrendered.

Emperor Theodore III, rather than surrender, shot himself.

The palace fortress of Magdala fell to Napier’s troops without further struggle.

On 17th April 1868 Napier’s force began the march back to the coast with the released prisoners, leaving Magdala to Theodore’s Queen Masteeat.

Casualties at the Battle of Magdala:

In the fighting on the Aroge plain, British casualties were 20 wounded. The Abyssinians suffered 700 dead and 1,200 wounded.

There were virtually no casualties in the storming of Magdala on 13th April 1868.

During the whole campaign 11 officers and 35 British soldiers died, mainly through disease. Some 570 Indian soldiers were admitted to hospital, with an unspecified number of deaths.

Follow-up to the Battle of Magdala:

Napier withdrew to Annesley Bay, where the infrastructure established at Zula was dismantled and shipped back to India with the army and its followers.

By mid-June 1868, the British force left Abyssinia.

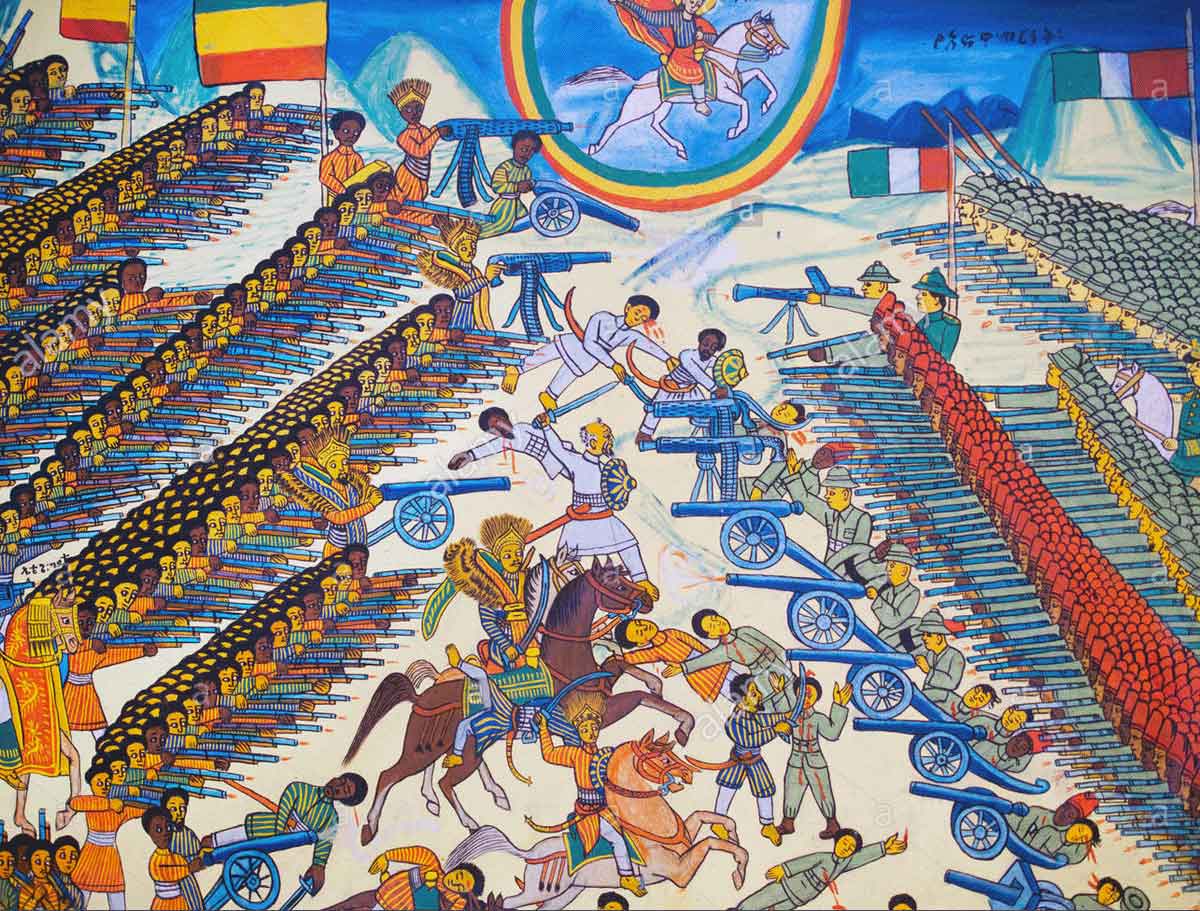

Ethiopian illustration of the Battle of Adowa in 1896 when an invading Italian army was annihilated by the Abyssinians

The new ruler of Abyssinia was King John, followed in 1881 by the Emperor Menelik, who resoundingly defeated an invading Italian army in 1896 at the Battle of Adowa.

Battle Honours and decorations:

Sir Robert Napier was promoted and given a peerage as Lord Napier of Magdala for his highly successful conduct of the Abyssinian expedition.

The Battle Honour ‘Abyssinia 1867-1868’ was awarded to the regiments that took part in the campaign.

A campaign medal was issued to the soldiers who took part.

Private Bergin and Drummer Magner of the 33rd Foot were awarded Victoria Crosses for their part in storming the wall by the Kukitber Gate into Magdala.

Anecdotes and traditions from the Battle of Magdala:

- For Napier’s war chest during the Abyssinia campaign, an arrangement was made with the Government in Vienna for the minting of several thousand Maria Theresa Thalers, this being the main form of currency in Abyssinia.

- After the capture of the palace fortress, Magdala was extensively looted by the British and Indian soldiers. The loot was taken from the soldiers and auctioned, with the proceeds being divided among the army. Valuable material was looted and sold, some of it ending up in the Victoria and Albert Museum in Kensington.

- The army was joined by the 45th Regiment, during the advance to Magdala, the regiment having marched 300 miles in 24 days through the difficult mountains, an average of 12 ½ miles a day.

- The Emperor Theodore II shot himself with one of a pair of pistols given to him by Queen Victoria some years before.

- One of the journalists accredited to Sir Robert Napier’s expeditionary force was H.M. Stanley, the American journalist who tracked down Livingstone and uttered the immortal words ‘Doctor Livingstone I presume’.

References for the Battle of Magdala:

Frontier and Overseas Expeditions from India Volume VI published by the Indian Army in 1911

British Battles by Grant

History of the British Army by Fortescue, Volume XIII

The Expedition to Abyssinia, 1867-8 by David Chandler (Victorian Military Campaigns edited by Brian Bond)

The previous battle in the British Battles series is the Siege of Delhi

The next battle in the British Battles series is the Battle of Ali Masjid