The Battle of Waterloo on 18th June 1815; the battle that ended the dominance of the French Emperor Napoleon over Europe; the end of an epoch

The previous battle of the Napoleonic Wars is the Battle of Quatre Bras

The next battle in the British Battles series is the Battle of Ghuznee

15. Podcast of the Battle of Waterloo: the battle fought on 18thJune 1815 that ended the dominance of the French Emperor Napoleon over Europe and saw the end of an epoch. John Mackenzie’s Britishbattles.com podcast.

15. Podcast of the Battle of Waterloo: the battle fought on 18thJune 1815 that ended the dominance of the French Emperor Napoleon over Europe and saw the end of an epoch. John Mackenzie’s Britishbattles.com podcast.

“Scotland for ever!” Lady Butler’s iconic picture of the Charge of the Royal Scots Greys, 2nd Dragoons, as part of the Union Brigade at the Battle of Waterloo on 18th June 1815

War: Napoleonic Wars

Date of the Battle of Waterloo: 18th June 1815

Place of the Battle of Waterloo: South of Brussels in modern Belgium

Combatants at the Battle of Waterloo: British, Germans, Belgians, Dutch and Prussians against the French Grande Armée

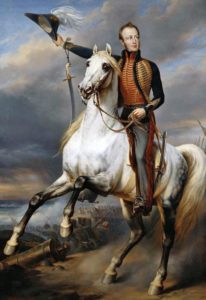

Commanders at the Battle of Waterloo: The Duke of Wellington, Marshal Blücher and the Prince of Orange against the Emperor Napoleon

Size of the armies at the Battle of Waterloo: 23,000 British troops with 44,000 allied troops and 160 guns against 74,000 French troops and 250 guns.

Winner of the Battle of Waterloo: The British, Germans, Belgians, Dutch and Prussian allies

Emperor Napoleon reviews his Guard: Battle of Waterloo on 18th June 1815: picture by Édouard Detaille

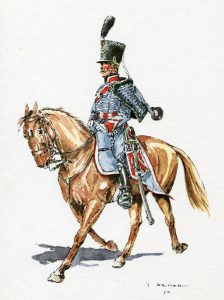

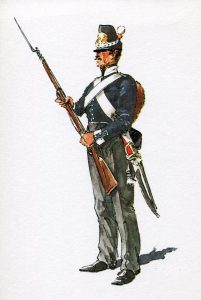

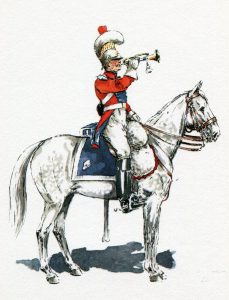

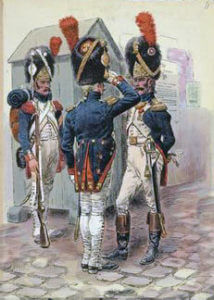

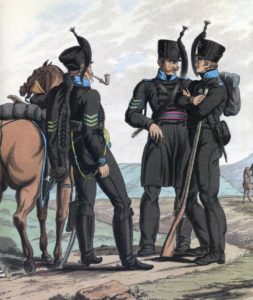

Uniforms, arms, equipment and tactics at the Battle of Waterloo:

The British infantry wore red waist jackets, grey trousers, and stovepipe shakos. Fusilier regiments wore bearskin caps. The two rifle regiments wore dark green jackets.

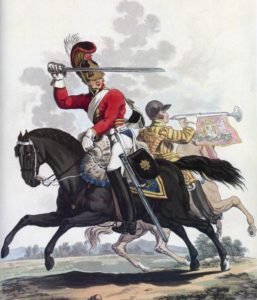

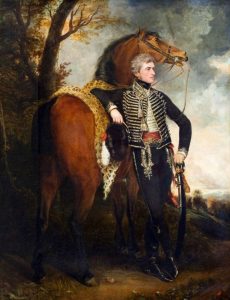

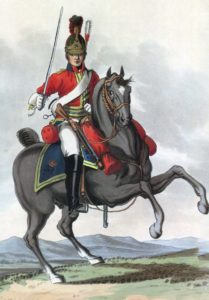

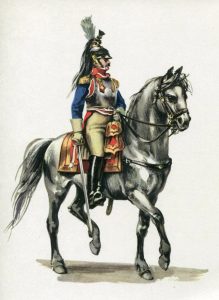

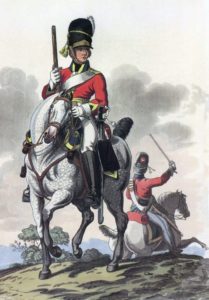

British heavy cavalry wore red tunics and roman-style crested helmets. The British light cavalry wore either the light blue of light dragoons or hussar uniforms of shabrach, dolman and busby.

The Royal Horse Guards and Royal Artillery wore blue tunics.

The Royal Horse Artillery wore blue uniforms with the old light dragoon style crested helmet.

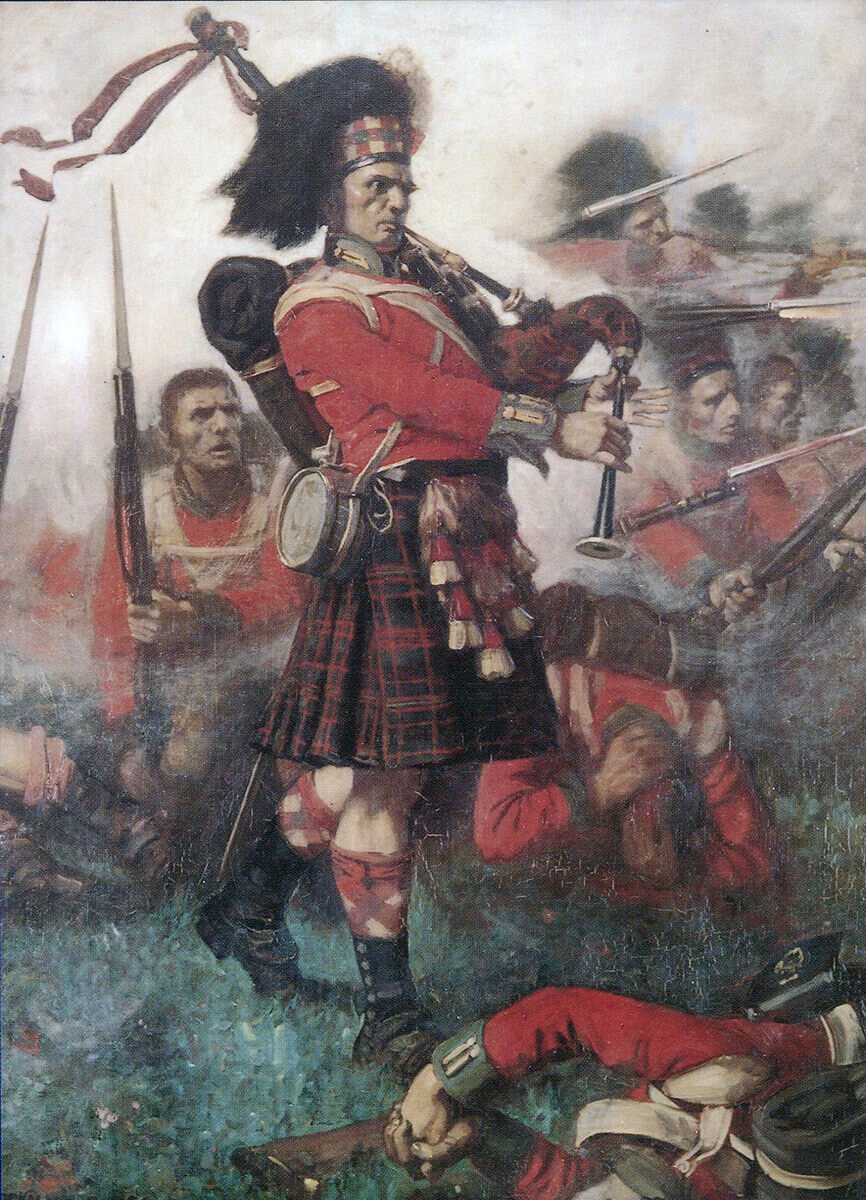

Highland regiments wore the kilt with red tunics and tall black ostrich feather caps.

Field Marshal Blucher, Prussian commander at the Battle of Waterloo on 18th June 1815: picture by Gebauer

The King’s German Legion (KGL) was the Hanoverian army in exile. The KGL owed its allegiance to King George III of Great Britain, as the Elector of Hanover, and fought with the British army. The KGL comprised both cavalry and infantry regiments. KGL uniforms mirrored the British, as did the regiments of the re-constituted Hanoverian army.

Belgians and Dutch wore dark blue.

The Brunswickers wore black uniforms.

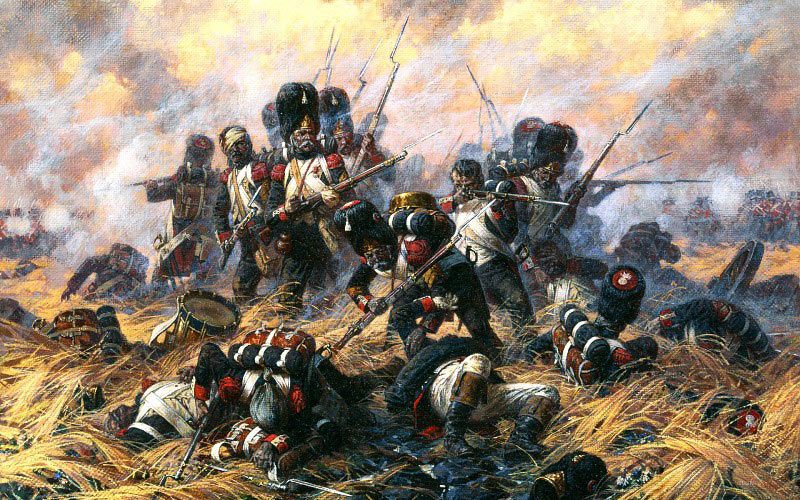

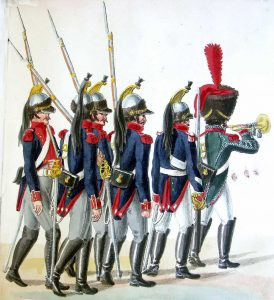

The French army wore a variety of uniforms. The basic infantry uniform was dark blue.

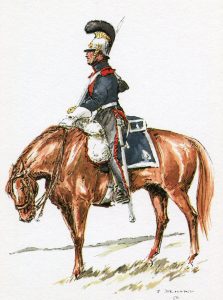

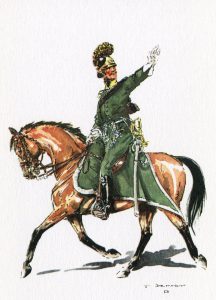

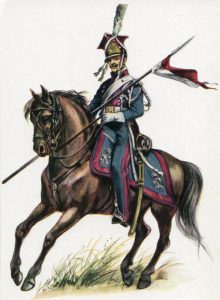

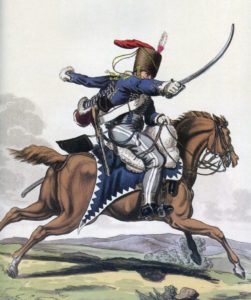

The French cavalry comprised Cuirassiers, wearing heavy burnished metal breastplates and crested helmets, Dragoons, largely in green, Hussars, in the conventional uniform worn by this arm across Europe, and Chasseurs à Cheval, dressed as hussars.

The Grenadiers of the Guard wore the characteristic tall bearskin that the British Foot Guards were to adopt after the battle.

The French foot artillery wore uniforms similar to the infantry, the horse artillery wore hussar uniforms.

The standard infantry weapon across all the armies was the muzzle-loading musket. The musket could be fired three or four times a minute, throwing a heavy ball inaccurately for a hundred metres or so. Each infantryman carried a bayonet for hand-to-hand fighting, which fitted the muzzle end of his musket.

The British rifle battalions (60th and 95th Rifles) carried the Baker rifle, a more accurate weapon but slower to fire, and a sword bayonet.

Field guns fired a ball projectile, of limited use against troops in the field unless those troops were closely formed. Guns also fired case shot or canister which fragmented and was highly effective against troops in the field over a short range. Exploding shells fired by howitzers, yet in their infancy. were of particular use against buildings. The British were developing shrapnel (named after the British officer who invented it) which increased the effectiveness of exploding shells against troops in the field, by exploding in the air and showering them with metal fragments.

Throughout the Peninsular War and the Waterloo campaign, the British army was plagued by a shortage of artillery. The Army was sustained by volunteer recruitment and the Royal Artillery was not able to recruit sufficient gunners for its needs.

Napoleon exploited the advances in gunnery technology of the last years of the French Ancien Régime, to create his powerful and highly mobile artillery. Many of his battles were won using a combination of the manoeuvrability and fire power of the French guns, with the speed of French columns of infantry, supported by the mass of French cavalry.

Provided the infantry were able to form square, they were largely impervious to cavalry attack, as neither the British nor the French cavalry horses could be brought to ride through an unbroken infantry line and the infantry could not be attacked in flank.

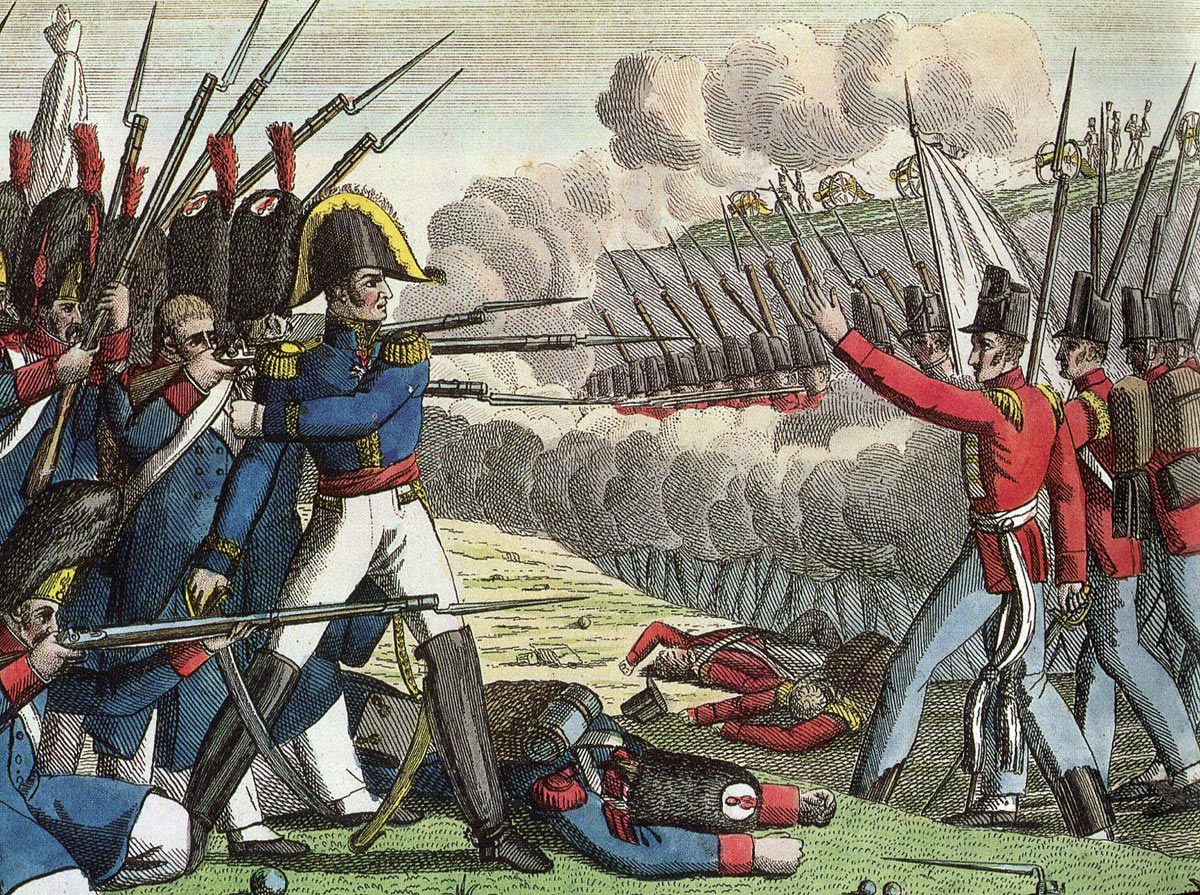

Third Regiment of Foot Guards (now Scots Guards) repulsing the attack of the Old Guard at the Battle of Waterloo on 18th June 1815: picture by Richard Simkin

While the French conscript infantry moved about the battle field in fast moving columns, the British trained to fight in line. The Duke of Wellington reduced the number of ranks to two, to extend the line of the British infantry and to exploit fully the firepower of his regiments.

British Regiments present at the Battle of Waterloo:

Royal Horse Artillery

1st Life Guards now the Life Guards

2nd Life Guards now the Life Guards

Royal Horse Guards now the Blues and Royals

King’s Dragoon Guards now the Queen’s Dragoon Guards

Royal Dragoons now the Blues and Royals

Royal Scots Greys now the Royal Scots Dragoon Guards

6th Inniskilling Dragoons later the 5th Inniskilling Dragoon Guards and now the Royal Dragoon Guards

7th Hussars later the Queen’s Own Hussars and now the Queen’s Royal Hussars

10th Hussars later the Royal Hussars and now the King’s Royal Hussars

11th Hussars later the Royal Hussars and now the King’s Royal Hussars

12th Light Dragoons now the 9th/12th Lancers

13th Light Dragoons later the 13th/18th King’s Royal Hussars and now the Light Dragoons

Duke of Wellington on the march from Quatre Bras to Waterloo: Battle of Waterloo on 18th June 1815; picture by Ernest Crofts

15th Light Dragoons later the 15th/19th Hussars and now the Light Dragoons

16th Light Dragoons later the 16th/5th Lancers and now the Queen’s Royal Lancers

18th Light Dragoons later the 13th/18th King’s Royal Hussars and now the Light Dragoons

23rd Light Dragoons (disbanded)

Royal Artillery

Royal Engineers

1st Foot Guards now the Grenadier Guards

2nd Coldstream Guards

3rd Foot Guards now the Scots Guards

1st Foot later the Royal Scots now the Royal Regiment of Scotland

4th King’s Own Regiment of Foot later the King’s Own Royal Border Regiment now the Duke of Lancaster’s Regiment

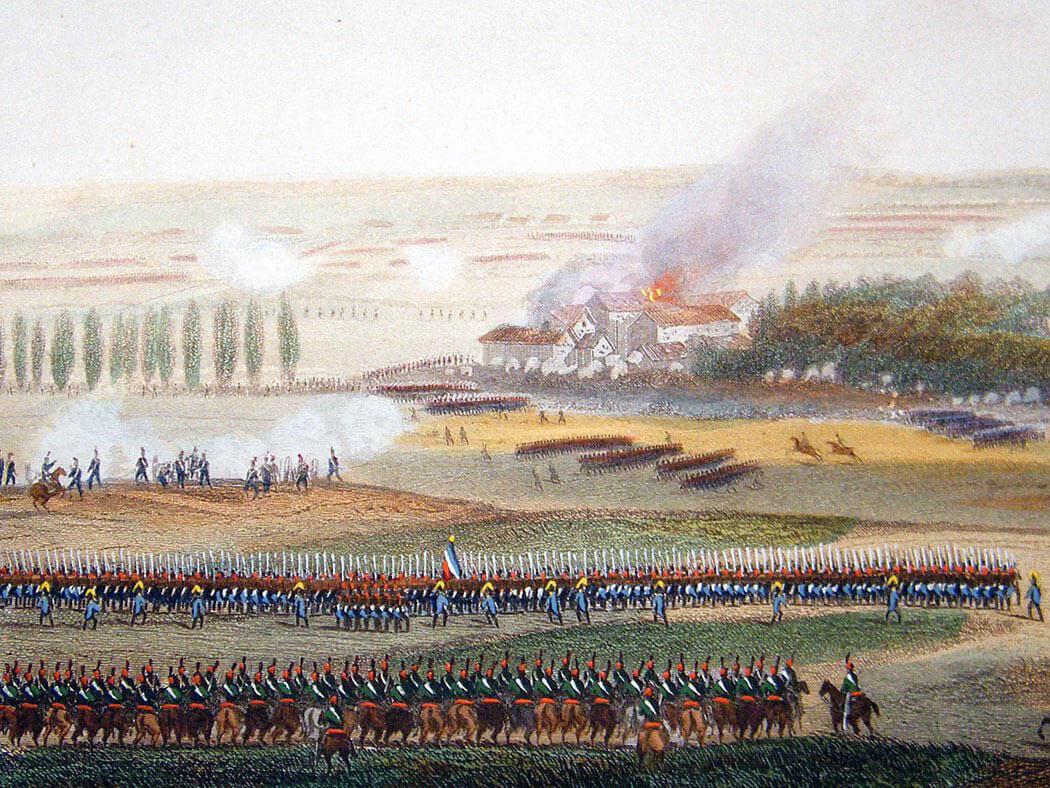

Final advance of the Allied line against the retreating French army at the Battle of Waterloo on 18th June 1815

14th Foot later the West Yorkshire Regiment later the Prince of Wales’s Own Regiment of Yorkshire now the Yorkshire Regiment

Royal Scots Greys 2nd Dragoons: Battle of Waterloo 18th June 1815: picture by Charles Hamilton Smith

23rd Royal Welch Fusiliers now the Royal Welsh

27th Foot, the Inniskilling Fusiliers and now the Royal Irish Regiment

28th Foot later the Gloucestershire Regiment and now the Royal Gloucestershire, Berkshire and Wiltshire Regiment now the Rifles

30th Foot later the East Lancashire Regiment later the Queen’s Lancashire Regiment now the Duke of Lancaster’s Regiment

32nd Foot later the Duke of Cornwall’s Light Infantry later the Light Infantry now the Rifles

33rd Foot the Duke of Wellington’s Regiment now the Yorkshire Regiment

40th Foot later the South Lancashire Regiment later the Queen’s Lancashire Regiment now the Duke of Lancaster’s Regiment

42nd Highlanders later the Black Watch (the Royal Highland Regiment) now the Royal Regiment of Scotland

44th Foot later the Essex Regiment and now the Royal Anglian Regiment

51st Light Infantry later the King’s Own Yorkshire Light Infantry later the Light Infantry now the Rifles

52nd Light Infantry capturing a French artillery battery at the Battle of Waterloo on 18th June 1815: picture by Ernest Crofts

Gunners of the Royal Artillery: Battle of Waterloo 18th June 1815: picture by Charles Hamilton Smith

52nd Light Infantry later the Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry later the Royal Green Jackets now the Rifles

69th Foot later the Welsh Regiment and now the Royal Regiment of Wales

71st Highland Light Infantry later the Royal Highland Fusiliers now the Royal Regiment of Scotland

73rd Highlanders the Black Watch now the Royal Regiment of Scotland

79th Highlanders later the Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders, later the Queen’s Own Highlanders now the Royal Regiment of Scotland

92nd Highlanders the Gordon Highlanders now the Royal Regiment of Scotland

95th Rifles later the Rifle Brigade later the Royal Green Jackets now the Rifles

Duke of Wellington and his staff at the Battle of Waterloo on 18th June 1815 with the Prince of Orange wounded in the bottom left corner

15. Podcast of the Battle of Waterloo: the battle fought on 18thJune 1815 that ended the dominance of the French Emperor Napoleon over Europe and saw the end of an epoch. John Mackenzie’s Britishbattles.com podcast.

15. Podcast of the Battle of Waterloo: the battle fought on 18thJune 1815 that ended the dominance of the French Emperor Napoleon over Europe and saw the end of an epoch. John Mackenzie’s Britishbattles.com podcast.

Background to the Battle of Waterloo:

In 1814, twenty-five years of war came to an end with the surrender of the Emperor Napoleon and his banishment to the Mediterranean island of Elba. The European powers began the task of restoring their continent to normality and peace. The Bourbons resumed their interrupted reign in France with King Louis XVIII.

On 1st March 1815, Napoleon escaped from Elba and landed in France. Nineteen days later, Napoleon was in Paris and resumed his title of Emperor. Napoleon’s army rallied to him. The many French soldiers, captured during the years of fighting up to 1814 and now released, enabled Napoleon to reform his powerful Grande Armée.

Morning of the Battle of Waterloo on 18th June 1815: the French await the Emperor Napoleon’s orders: picture by Ernest Crofts

The European allies reassembled their armies and prepared to resume the war to overthrow the Emperor yet again.

Napoleon resolved to attack the British, Prussian, Belgian and Dutch armies before the other powers could come to their assistance. He marched into the area that is now Belgium.

Napoleon defeated the Prussians, under Marshall Blücher, at the Battle of Ligny on 16th June 1815, driving the Prussians away to the east.

On the same day, Marshal Ney fought the Battle of Quatre Bras against troops of the Duke of Wellington’s allied army, forcing Wellington to fall back towards Brussels.

Napoleon sent Marshal Grouchy in pursuit of the Prussians, while he advanced on Wellington’s army.

Assured by Blücher that the Prussians would join him for the conclusive battle against Napoleon, Wellington, on the afternoon of 17th June 1815, halted his army to give battle to the French.

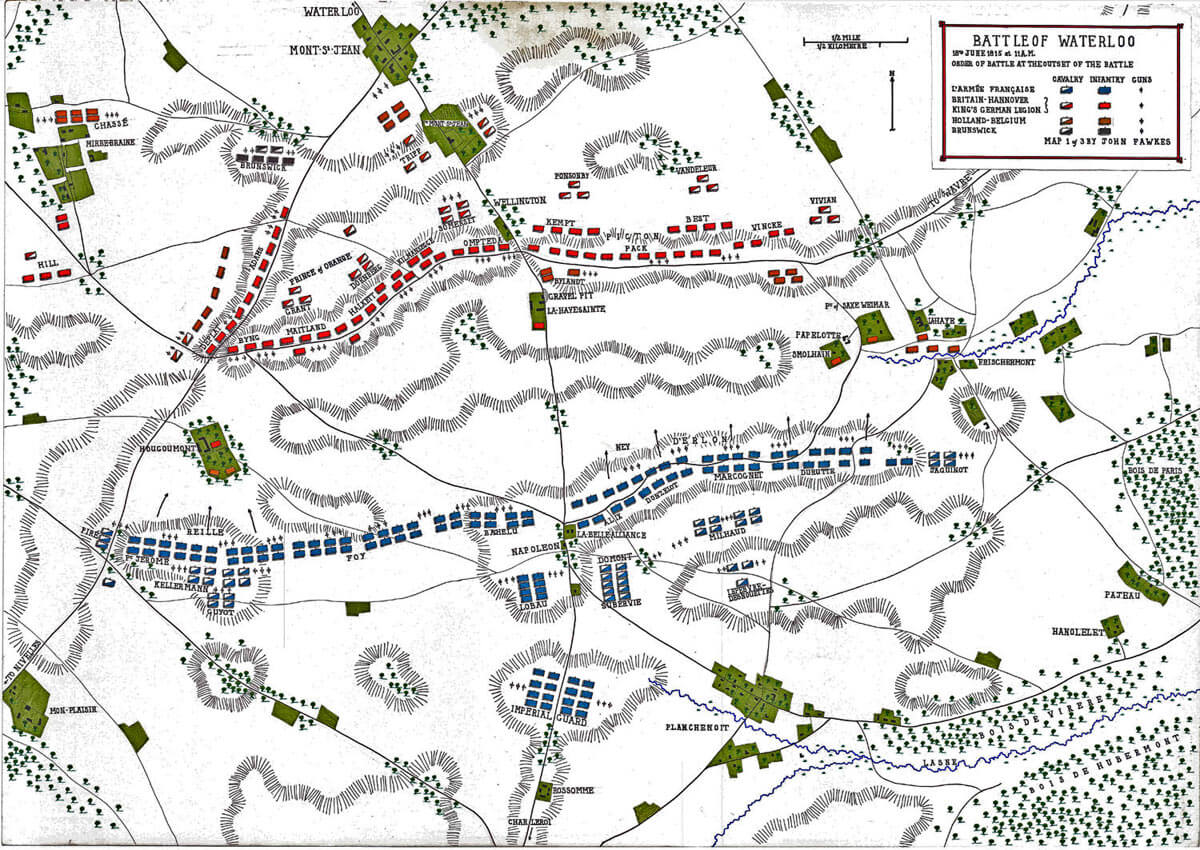

The Duke of Wellington took up a position on the Brussels road, where it emerges from the woods of Soignies, south of the village of Waterloo. The road crosses a low ridge, behind which Wellington positioned his army facing south, and descends into a valley before rising on the other side to a further ridge. In the valley, below the first crest, lay La Haye Sante Farm and on the road at the southern side of the valley, below the second crest, stood La Belle Alliance Farm.

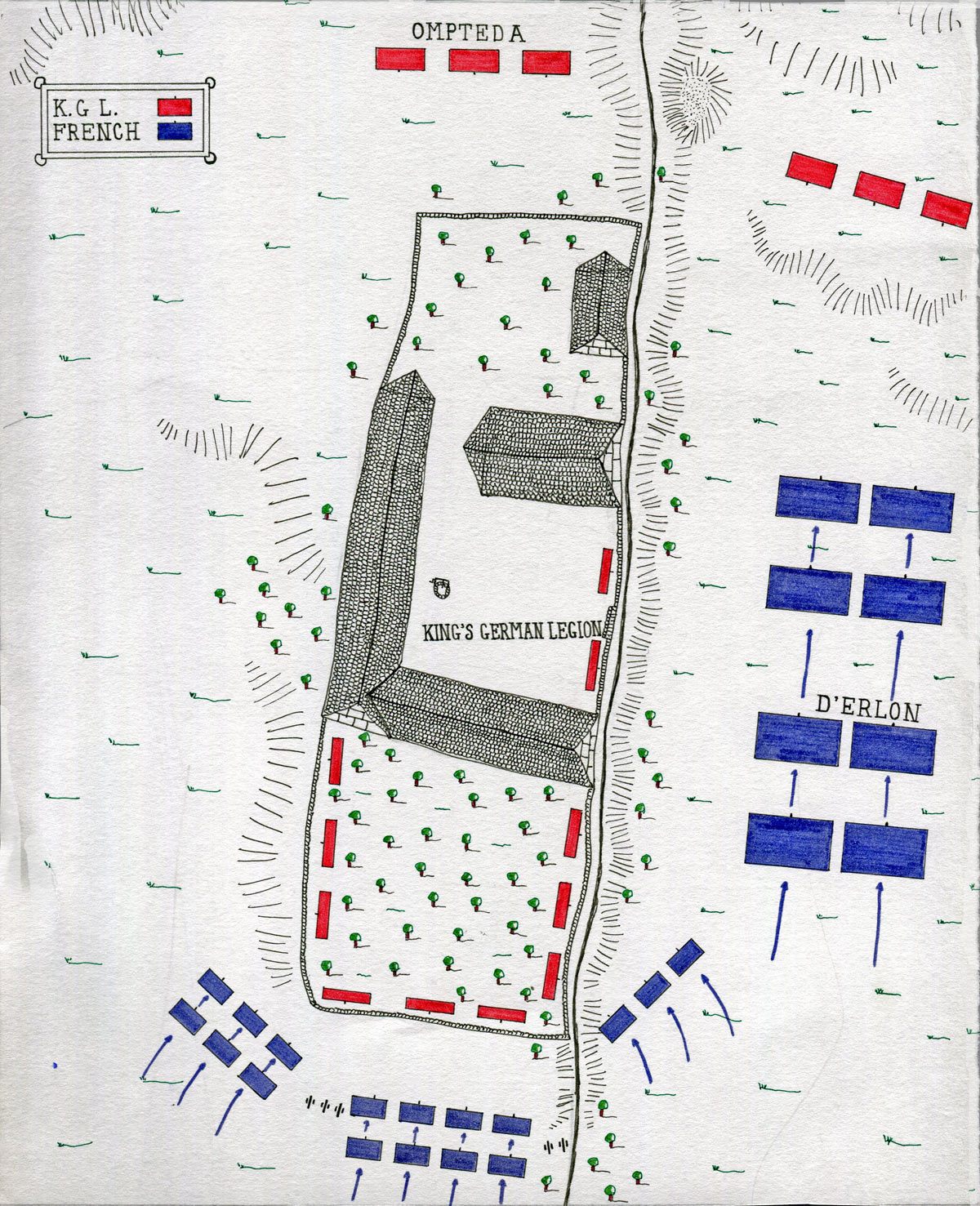

During most of the Battle of Waterloo, the Germans occupied La Haye Sante and the French used La Belle Alliance as a headquarters.

To the north of the first crest, the Namur road crossed the Brussels road. The main British, German, Belgian and Dutch positions lay along the Namur road, behind the first crest. The French approach to the battle was from the country to the South of La Belle Alliance and across the valley.

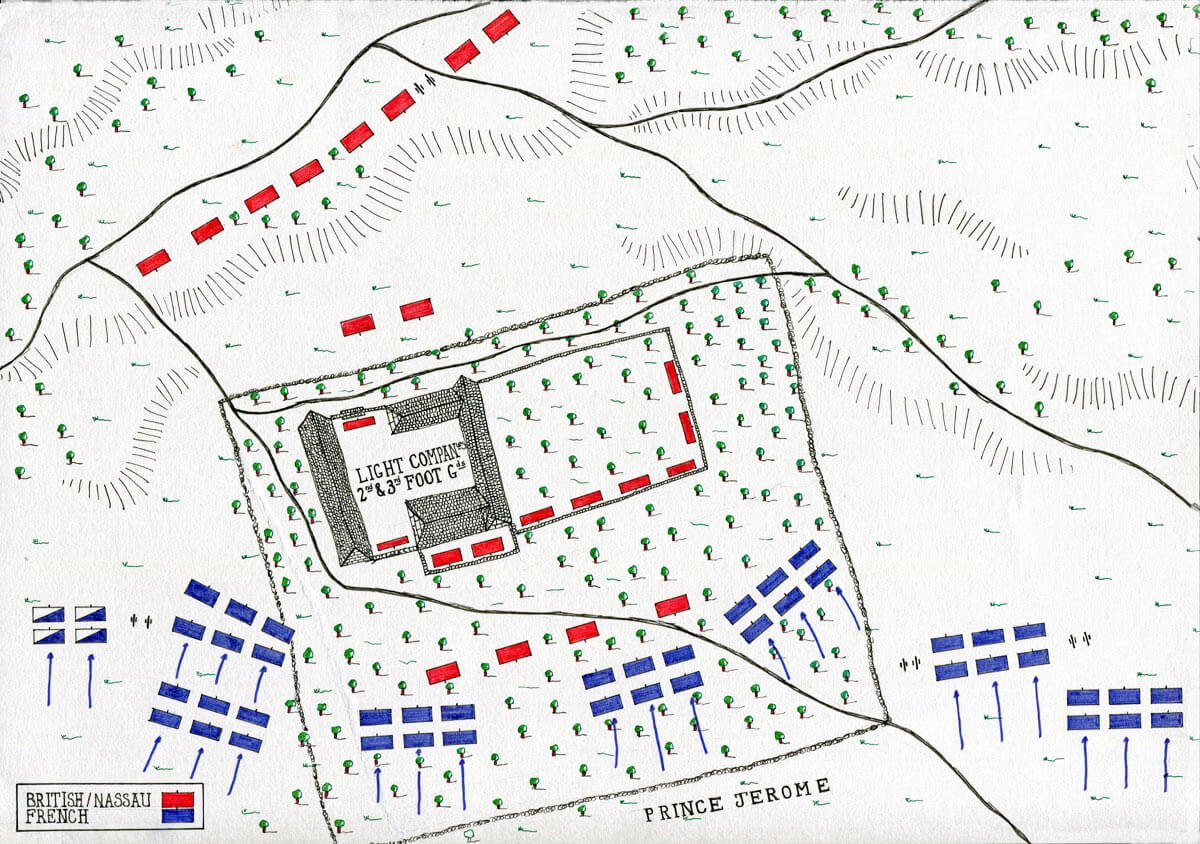

In the valley to the front of the right wing of the Allied line, stood Hougoumont Farm, the key to Wellington’s right flank. Held by the light companies of the British Coldstream and Third Guards, there would be fighting around Hougoumont all day during the battle.

‘Last Reveille’ sounded by French Dragoons: Dawn of the Battle of Waterloo on 18th June 1815: picture by Lady Butler

Lying by the road leading to the centre of Wellington’s position, the capture of La Haye Sante was a crucial goal for the French army.

To the east of the Duke’s army lay Papelotte, another farm that would be the centre of a ferocious struggle, particularly as the Prussian Army appeared on the field at the end of the battle.

In the Duke’s centre stood the farm of Mont St Jean, used as a headquarters and hospital.

Reveille for the Royal Scots Greys: Dawn of the Battle of Waterloo on 18th June 1815: picture by Lady Butler

It rained heavily during the night of 17th June 1815. The French artillery commanders insisted to Napoleon that the French attack did not begin until the ground had dried out sufficiently for the guns to manoeuvre without sticking in the mud.

The French attack began at 11am on 18th June 1815.

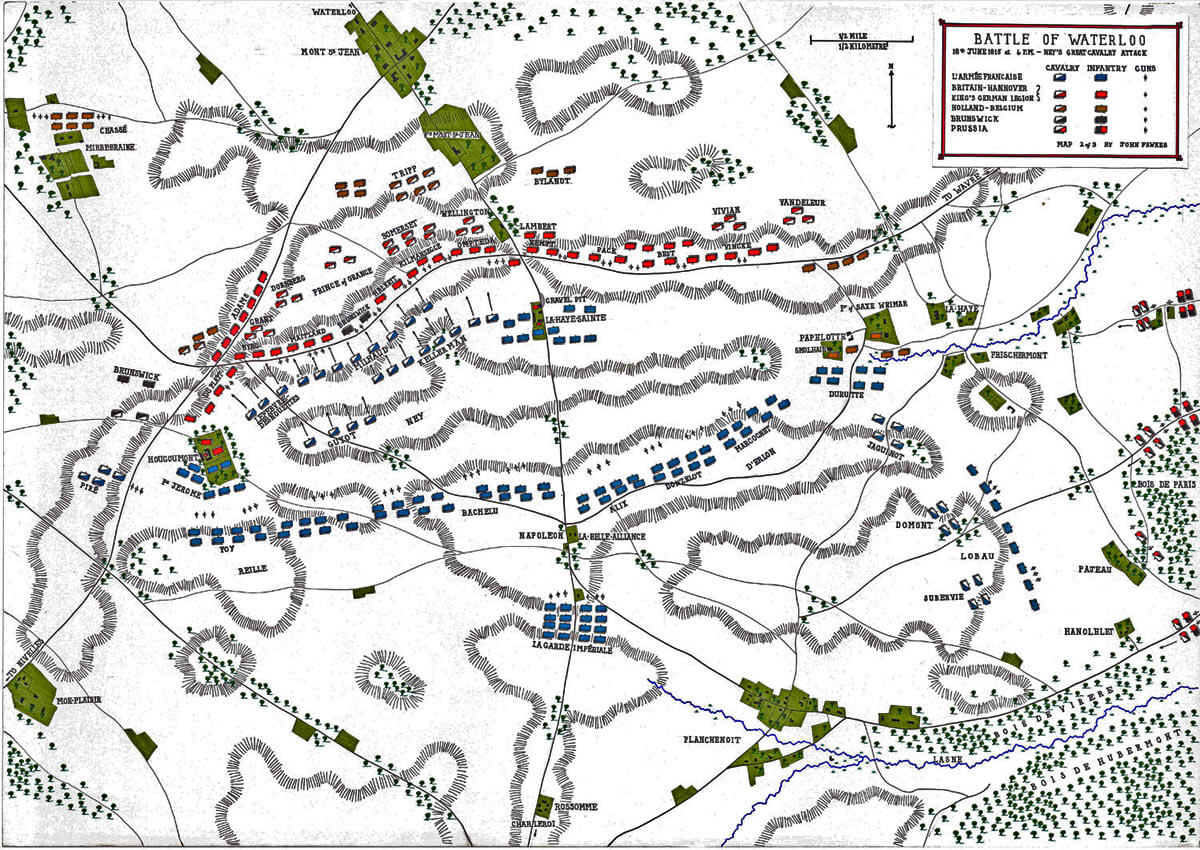

Map of the Battle of Waterloo at 4pm on 18th June 1815: Ney’s Great Cavalry Attack: map 2 by John Fawkes

Account of the Battle of Waterloo:

At 11am on 18th June 1815, the French bombardment of Hougoumont Farm, on the extreme right of the Allied line, began the battle. The British artillery on the ridge behind the farm replied, cannonading the French infantry massed for the attack on the far side of the valley.

At midday, Prince Jerome ordered the assault on Hougoumont and the French infantry columns of his division moved forward to begin the day long struggle around the farm buildings.

15. Podcast of the Battle of Waterloo: the battle fought on 18thJune 1815 that ended the dominance of the French Emperor Napoleon over Europe and saw the end of an epoch. John Mackenzie’s Britishbattles.com podcast.

15. Podcast of the Battle of Waterloo: the battle fought on 18thJune 1815 that ended the dominance of the French Emperor Napoleon over Europe and saw the end of an epoch. John Mackenzie’s Britishbattles.com podcast.

At about 1.30pm, Marshal Ney brought forward 74 French guns over the ridge opposite La Haye Sante, followed by the 17,000 infantry of D’Erlon’s corps, to begin the attack on the Duke of Wellington’s centre and left.

Charge of the British Life Guards at the Battle of Waterloo on 18th June 1815: picture by Luke Clennel

The French cannonade began and was later described by Allied veterans as the heaviest they had experienced. The Duke ordered his infantry battalions to move back behind the ridge and to lie down. This had the effect of shielding them from the worst of the cannonade. Only Bilandt’s Belgian-Dutch Brigade was left on the exposed slope and suffered heavily.

After half an hour, the barrage stopped, giving way to the roar of drums as Ney’s columns advanced to the attack.

The French infantry passed La Haye Sante and marched up to the crest of the ridge, where Picton’s 5th division was positioned.

As part of the French advance, a furious assault began on La Haye Sante, held by the King’s German Legion, which was to continue intermittently for the rest of the day, until the German troops ran out of ammunition and were finally overwhelmed.

As the French infantry approached the hedge at the top of the ridge, the line of British infantry stood up, fired a volley and charged, driving back the massed French columns.

Royal Horse Guards (the Blues) in the charge at the Battle of Waterloo on 18th June 1815: picture by Christopher Clark

Allied Cavalry formations, mostly British regiments, were ordered to charge in support of the infantry attack; the Household Brigade (1st and 2nd Life Guards and Royal Horse Guards), the Union Brigade (Royals, Scots Greys and Inniskillings) and Vivian’s Hussar Brigade (10th and 18th Hussars and 1st Hussars, King’s German Legion).

It is notoriously difficult to pull up cavalry committed to a charge, and the British regiments did not readily respond to recall orders. The Union Brigade continued to attack across the valley. These regiments charged up to the French gun line on the far ridge, where they were in turn overwhelmed by French cavalry.

Ponsonby’s Union Brigade (troopers from the 6th Inniskillings, Scots Greys and Royal Dragoons) charging at the Battle of Waterloo on 18th June 1815

General Ponsonby, commanding the Union Brigade was killed. It is of note that, of the three regiments in the Union Brigade, two, the Greys and Inniskillings, had not served in the Peninsular War and lacked battle experience.

British 10th Hussars attacking the French infantry at the Battle of Waterloo on 18th June 1815: picture by Denis Dighton

The time was 3pm and there was a lull in the battle, the only active fighting being the continuing attack on Hougoumont at the western end of the line, sucking in more and more of Reille’s French corps.

The battle began slowly to swing in the Allies’ favour as Blücher’s Prussian Army arrived on the field in the south-east.

British Union Brigade counterattacked by French Cuirassiers and Lancers at the Battle of Waterloo on 18th June 1815: picture by Chartier

Napoleon ordered Ney to capture La Haye Sante, considering the farm to be the key to the Allied position. Ney launched this assault with two battalions he found to hand and, during the operation, formed the view that the Allied army was withdrawing. It is likely that the movements he saw were casualties or prisoners moving to the rear.

Ponsonby’s Union Brigade (troopers from the Royal Dragoons) charging at the Battle of Waterloo on 18th June 1815

It was on this impetuous assumption that Ney launched his massive cavalry attack on the Allied line.

Initially the attacking force was Milhaud’s French Cavalry Corps of Cuirassiers.

Before the French could reach the Allied line, the infantry formed squares interlaced with artillery batteries. The French cuirassiers flowed around the squares, but were unable to penetrate them.

French Cuirassiers tumbling into the sunken road on the ridge during Ney’s Great Cavalry Attack: Battle of Waterloo on 18th June 1815

During the next three hours, some twelve French cavalry attacks were made up to the ridge and back.

Napoleon, while deprecating the initial attack as premature, felt bound to commit increasing numbers of cavalry to support the assault.

French cavalry attacking British squares during Ney’s Great Cavalry Attack: Battle of Waterloo on 18th June 1815: picture by Denis Dighton

At around 5.30pm, Ney launched the final French cavalry charge. There were too many regiments, fresh mingled with exhausted. The attack failed yet again.

French Cuirassiers attacking a Highland Regiment in Square at the Battle of Waterloo on 18th June 1815: picture by Felix Philippoteaux

Ney now launched the sustained infantry assault on La Haye Sante, which was overwhelmed.

This success was too late to change the outcome of the battle, as the Prussian assault in the south-east, on Plancenoit, was seriously threatening the French position.

Sure that the Allied line was at breaking point, Ney sent desperately to the Emperor for more troops to attack.

Emperor Napoleon and his Imperial Guard at the Battle of Waterloo on 18th June 1815: picture by Harry Payne

Napoleon was at this point deploying the Guard, to drive the Prussians back from Plancenoit. Once this had been achieved, Napoleon resolved to launch the Guard at the main Allied line.

By the time the Guard was available to carry out the attack on the ridge, Wellington had reorganised his forces, and the opportunity, that Ney had this time correctly identified, had passed.

As the Guard began its advance on the ridge, a deserting French cavalry officer galloped up to the Allied line and warned of the Guard’s approach.

The Guard marched up to La Belle Alliance, where Napoleon stood aside and left the command of the attack to Ney.

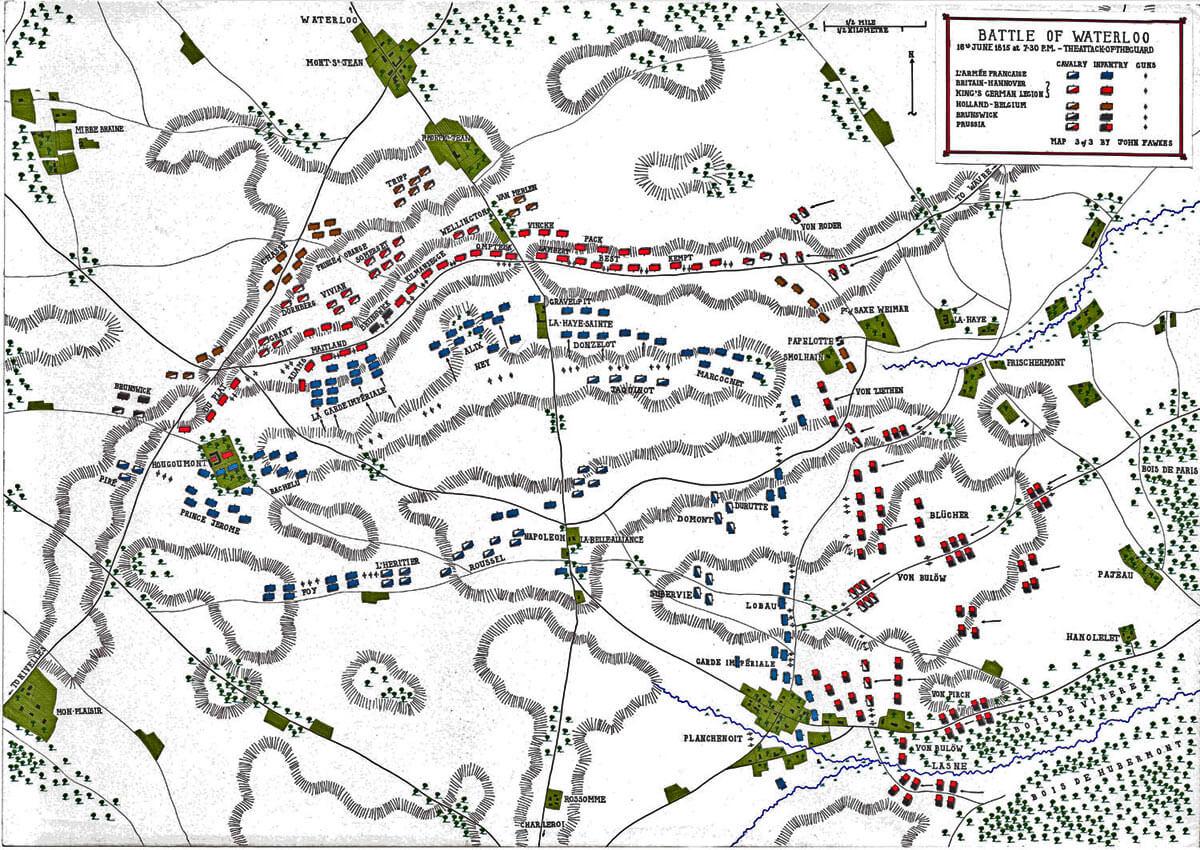

Map of the Battle of Waterloo at 7pm on 18th June 1815: the Attack of the French Imperial Guard: map 3 by John Fawkes

Ney led the five battalions up the left-hand side of the Brussels road. As they climbed the ridge, the columns came under fire from a curve of Allied batteries assembled to meet them.

The Middle Guard threw back the British battalions of Halkett’s Brigade, but were assaulted by the Belgian and Dutch troops of General Chassé and Colonel Detmers, who drove them back down the hill.

The 3rd Regiment of Chasseurs approached the ridge opposite Maitland’s Brigade of Foot Guards (2nd and 3rd Battalions of the 1st Foot Guards). Wellington called to the brigade commander ‘Now Maitland. Now’s your time’. One authority had Wellington saying ‘Up Guards, ready’. The 1st Foot Guards stood, fired a volley and charged with the bayonet, driving the French Guard back down the hill.

Attack of the 52nd Light Infantry on the Imperial Guard at the Battle of Waterloo on 18th June 1815: picture by Laslett J. Pott

The last of the French Guard regiments, the 4th Chasseurs, came up in support as the British Guards withdrew over the ridge.

Sir John Colborne brought the 52nd Foot round to outflank the French column, as it passed his brigade, fired a destructive volley into the left flank of the Chasseurs and attacked with the bayonet. The whole of the Guard was driven back down the hill and the French army began a general retreat to the cry of ‘La Garde recule’.

Within fifteen minutes, Wellington appeared on the skyline and waved his hat to give the signal for a general attack in pursuit of the French troops. The British, Belgian, Dutch and German troops poured forward and the French retreat became a route.

‘The Whole Line Will Advance’: the Duke of Wellington ordering the attack at the end of the Battle of Waterloo on 18th June 1815

Three battalions of the Old Guard fought to the end, to enable the Emperor to escape from the battlefield, as the Allied troops including the Prussians closed in. General Cambronne is reputed to have answered a call to surrender with the words ‘The Guard dies but does not surrender’.

The Battle of Waterloo ended with an historic meeting between the Duke of Wellington and Marshal Blücher, who had kept his promise to Wellington to come to his assistance.

Duke of Wellington meets Marshal Blücher at the end of the Battle of Waterloo on 18th June 1815: picture by William Heath

15. Podcast of the Battle of Waterloo: the battle fought on 18thJune 1815 that ended the dominance of the French Emperor Napoleon over Europe and saw the end of an epoch. John Mackenzie’s Britishbattles.com podcast.

15. Podcast of the Battle of Waterloo: the battle fought on 18thJune 1815 that ended the dominance of the French Emperor Napoleon over Europe and saw the end of an epoch. John Mackenzie’s Britishbattles.com podcast.

The Role of the Prussian Army under Marshal Blücher:

The effect of the Prussian attack on Napoleon’s right flank was decisive in enabling the Allies to win the Battle of Waterloo. The third map showing the position at 7pm on 18th June 1815 illustrates the effect of the Prussian assault on the French and the relief that it brought to the Allied army positioned along the ridge.

Prussian attack on Plancenoit at the Battle of Waterloo at around 7pm on 18th June 1815: picture by Adolf Northern

The British elevation of the Battle of Waterloo to the status of a national icon has resulted in many British accounts of the battle failing to do justice to the conduct at the battle of other nationalities forming the Allied army, particularly the contribution of the Prussian army.

General von Ziethen’s Prussian cavalry attacking the French right wing at the climax of the Battle of Waterloo on 18th June 1815

The Battle of Waterloo could not have been won if Marshal Blücher had not fulfilled his promise to the Duke of Wellington and delivered his devastating attack on Napoleon’s right flank around Plancenoit.

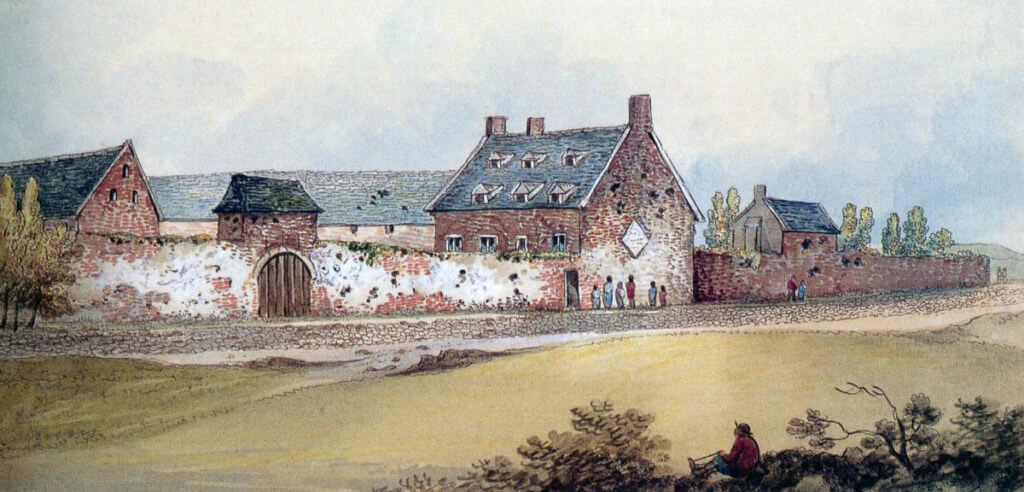

The Battle of Waterloo: Hougoumont Château

The small château of Hougoumont stood before the extreme right of the Allied position. The Duke of Wellington formed the view that the château was the key to his flank, and garrisoned it with the light companies of the Coldstream and 3rd Foot Guards under Lieutenant Colonel James MacDonnell of the Coldstream Guards. Nassauers and guardsmen held the woods to the front of the building.

French attack on Hougoumont Château at the Battle of Waterloo on 18th June 1815: picture by Ernest Crofts

The British troops took over the range of château buildings on 17th June 1815 and spent the night fortifying them, building fire steps and loop holing the walls. All the gates were blocked, other than the main gate on the northern side to provide access.

At 11am on 18th June, Prince Jerome’s division began the battle with his attack on Hougoumont, the French driving the Nassauers out of the woods and attacking the château.

The French surged around the buildings and charged the main gate, in the face of a rush of British guardsmen, headed by Colonel MacDonnell, to keep them out. The entrance was damaged and there ensued a struggle by the British to shut the gate and by the French to force it open.

The struggle to close the gates of Hougoumont Château: Battle of Waterloo on 18th June 1815: picture by Richard Gibb

Colonel MacDonnell and his party of officers and sergeants forced the gate shut and Sergeant Graham of the Coldstream Guards put the bar in place. The few French soldiers who had penetrated the entrance were hunted through the farm buildings.

During the rest of the day, Hougoumont was subject to sustained attack by Jerome’s troops, with assistance from a further French division. The château garrison was reinforced with more companies from the two Foot Guards battalions of Byng’s Guards Brigade, 2nd/2nd and 2nd/3rd Guards.

Coldstreamers defending the gate of Hougoumont Château at the Battle of Waterloo on 18th June 1815: picture by Ernest Crofts

When, during the afternoon the supply of ammunition in the château became critically low, Sergeant Fraser of the 3rd Guards went to the main line and returned with a wagon of cartridges, thereby enabling the defence to continue.

By the end of the battle, the château had been set ablaze by howitzer shells and the buildings were heaped with British casualties. The French were unable to capture Hougoumont, and their casualties filled the woods and fields around it.

The two battalions that defended Hougoumont suffered 500 dead and wounded out of a strength of 2,000 men.

Some years after the Battle of Waterloo, an English clergyman bequeathed £500 to be given to the bravest Briton from the battle. The selection was referred to the Duke of Wellington, who nominated Lieutenant Colonel McDonnell of the Coldstream Guards, for his defence of the Château of Hougoumont. Colonel McDonnell gave half the sum to Sergeant Graham, the soldier who put the gate bar in place.

Annually, the Coldstream Guards celebrate the defence of Hougoumont, with the ceremony of the hanging of the brick.

15. Podcast of the Battle of Waterloo: the battle fought on 18thJune 1815 that ended the dominance of the French Emperor Napoleon over Europe and saw the end of an epoch. John Mackenzie’s Britishbattles.com podcast.

15. Podcast of the Battle of Waterloo: the battle fought on 18thJune 1815 that ended the dominance of the French Emperor Napoleon over Europe and saw the end of an epoch. John Mackenzie’s Britishbattles.com podcast.

The Battle of Waterloo: La Haye Sante Farm

The farm of La Haye Sante stands on the west side of the main Brussels road, beneath the ridge, two hundred metres in front of the centre of the Allied position. As the Emperor Napoleon urged on Marshal Ney, La Haye Sante was the key to the Allied line and had to be taken at all costs.

The garrison, to whom it fell to resist the French attack, that began soon after D’Erlon’s assault, was from Major Baring’s 2nd Light Battalion of Colonel Baron Ompteda’s 2nd King’s German Legion Brigade.

La Haye Sainte after the battle: defended by the King’s German Legion at the Battle of Waterloo on 18th June 1815

The King’s German Legion expected only to spend the night in the farm, and did not discover until the morning that they were required to hold it for the battle. By then, the main gates had been burnt on the soldiers’ camp fires and little could be done to put the farm in a state of defence in the short time before the battle began.

The KGL soldiers of the farm garrison were largely spectators as D’Erlon’s attack swept past and up the ridge to the main Allied position, to be pursued back to their lines by the British cavalry counter-attack.

It was then that Ney’s attack on the farm was launched, on the orders of the Emperor Napoleon. From that moment, the King’s German Legion troops fought for their lives until late in the afternoon, when, with their ammunition finished and the farm in flames, the garrison was annihilated or driven out. 39 of some 360 soldiers survived the battle.

Charge of the Royal Scots Greys at the Battle of Waterloo on 18th June 1815: picture by Orlando Norie

Eagle of the French 45th of the Line, captured by the Royal Scots Greys at the Battle of Waterloo on 18th June 1815

Royal Scots Greys at the Battle of Waterloo:

At around 2pm, Major General Ponsonby’s Union Brigade of heavy dragoons, 1st Royal Dragoons, 2nd Royal Scots Greys and 6th Inniskilling Dragoons, charged D’Erlon’s infantry columns as they reached the British line.

As the Greys passed the 92nd Gordon Highlanders, the Gordons attempted to advance with them, holding the trooper’ stirrups.

The charge built up momentum and the British ‘Heavies’ launched themselves on the French infantry, the Greys shouting ‘Scotland for ever’.

Sergeant Ewart of the Royal Scots Greys capturing the Standard and Eagle of the French 45th of the Line at the Battle of Waterloo on 18th June 1815: picture by Sutherland

Sergeant Charles Ewart of the Greys rode at the officer of the 45th Infantry carrying the regimental standard, incorporating an Imperial Eagle at the top of the staff. Ewart cut down the four escorts and the standard bearer and bore the standard and eagle away.

The Union Brigade cut through the French infantry and, now out of control, continued the charge across the valley and up the far incline to the French guns, where they sabred a number of gunners.

Charge of the Royal Scots Greys at the Battle of Waterloo on 18th June 1815: picture by Henri Dupray

The British cavalry were counter-attacked by French Lancers and suffered such heavy casualties as to eliminate the brigade from the battle. The brigade commander, General Ponsonby, was killed.

As the Duke of Wellington grumblingly complained, ‘the British cavalry never know when to stop charging’.

Throughout this encounter, Ewart defended his captured French standard and eagle against repeated attacks by French cavalrymen, attempting to recover the lost emblem.

The Greys adopted the captured French eagle as the regiment’s badge. It is still the badge of the present regiment, the Royal Scots Dragoon Guards.

Royal Scots Greys and 92nd Gordon Highlanders at the Battle of Waterloo on 18th June 1815: picture by Stanley Berkeley

The Emperor Napoleon is said to have commented of the regiment, ‘Ah ces terribles chevaux gris’.

Sergeant Ewart of the Royal Scots Greys capturing the Standard and Eagle of the French 45th of the Line at the Battle of Waterloo on 18th June 1815: picture by Denis Dighton

The rest of the British Army wryly gave the Royal Scots Greys the nickname of ‘the Bird Catchers’.

After the battle, Sergeant Ewart was promoted ensign. The capture of the eagle was a powerful image in Victorian Scotland. Ewart died in England in 1846. His remains were buried in Edinburgh Castle.

Sergeant Ewart of the Royal Scots Greys defending the captured Standard and Eagle of the French 45th of the Line at the Battle of Waterloo on 18th June 1815: picture by Richard Ansdell

Casualties at the Battle of Waterloo:

The British, Belgians, Dutch and Germans lost 15,000 casualties or 1 in 4 engaged. The Prussians lost 7,000 men killed and wounded. The casualties in the French army are estimated at 25,000 dead and wounded, 8,000 prisoners and 220 guns lost.

15. Podcast of the Battle of Waterloo: the battle fought on 18thJune 1815 that ended the dominance of the French Emperor Napoleon over Europe and saw the end of an epoch. John Mackenzie’s Britishbattles.com podcast.

15. Podcast of the Battle of Waterloo: the battle fought on 18thJune 1815 that ended the dominance of the French Emperor Napoleon over Europe and saw the end of an epoch. John Mackenzie’s Britishbattles.com podcast.

Follow-up to the Battle of Waterloo:

Waterloo decisively saw the end of 26 years of fighting between the European powers and France. The French star was eclipsed and the German began its ascendancy.

For Britain, Waterloo is not just a battle. It is an institution (as well as a station).

Decorations and Battle Honours:

The Waterloo medal was issued to every officer and soldier who had taken part in the Battle of Waterloo, the Battle of Quatre Bras or the Battle of Ligny. In addition, two years seniority and pay was awarded. Each medal was inscribed with the recipient’s name around the rim.

The following British regiments received the battle honour of ‘Waterloo’: 1st and 2nd Life Guards, Royal Horse Guards, 1st King’ Dragoon Guards, 1st Royal Dragoons, 2nd Dragoons Royal Scots Greys, 6th (Inniskilling) Dragoons, 7th Queen’s Own Hussars, 10th Prince of Wales’s Own Royal Hussars, 11th Light Dragoons, 12th Light Dragoons, 13th Light Dragoons, 15th Hussars, 16th Light Dragoons, 18th Hussars, 1st Foot Guards, Coldstream Guards, 3rd Foot Guards, Royal Scots, 4th King’ Own, 14th Regiment, 23rd Royal Welch Fusiliers, 27th (Inniskiling) Regiment, 28th, 30th, 32nd, 33rd, 40th, 69th, 42nd Black Watch, 73rd Highlanders, 44th, 51st, 52nd Light Infantry, 71st Highlander Light Infantry, 79th Cameron Highlanders, 92nd Gordon Highlanders and 95th Rifles.

Anecdotes and traditions from the Battle of Waterloo:

- The Royal Dragoons captured the eagle of the French 105th of the Line, in the charge of the Union Brigade, and subsequently adopted the eagle as its badge. The eagle is now worn as an arm badge by the Blues and Royals, the successor regiment. As with the Greys the regiment was given the nickname of the ‘Bird catchers’.

- After the Battle of Waterloo, the 1st Foot Guards was given the title ‘the Grenadier Guards’, to commemorate the regiment’s role in overthrowing the French Grenadiers of the Old Guard. All ranks were given the bearskin cap to wear.

- 14th Foot: The 3rd Battalion of the regiment fought at Waterloo. The battalion had been newly raised and was awaiting disbandment, having seen no service, when Napoleon escaped from Elba. The battalion crossed to Belgium and won the battle honour for the regiment. Most of the soldiers were under 20 years of age.

- The Emperor Napoleon, some years before Waterloo, presented to each of his marshals a silver snuff box. Marshal Ney’s snuffbox was looted from his carriage after the battle by a British officer. Some years later the snuffbox was presented to the officers of the 19th Foot, the Green Howards, who used it in their mess for formal occasions.

- The 27th Inniskilling Fusiliers, in the course of Ney’s cavalry attacks, was bombarded by a French horse artillery battery. By the end of the battle, the battalion had suffered 478 casualties from a pre-battle strength of 750. An officer from a nearby battalion, Captain Kincaid, commented that the 27th seemed to be lying dead in its square. Kincaid, a veteran of the Peninsular War, said ‘I had never thought there would be a battle where everyone was killed. This seemed to be it.’

-

Cast of the skull of Corporal John Shaw, 2nd Life Guards, killed at the Battle of Waterloo on 18th June 1815

Corporal John Shaw of the 2nd Life Guards was a noted prize fighter and skilled swordsman. During the Regiment’s repeated charges at the Battle of Waterloo, Shaw was separated from his comrades and attacked by several French cuirassiers. Shaw is reputed to have killed ten of them, before being wounded by a colonel of cuirassiers. Shaw killed the colonel, fighting after his sword broke with his helmet as a bludgeon. Shaw crawled away and died during the night of his extensive injuries. Sir Walter Scott obtained a plaster cast of Shaw’s skull. The cast is now in the Household Cavalry Museum.

- The 71st Highland Light Infantry captured a French cannon and fired the last shot of the Battle of Waterloo at the retreating French army.

- The Duke of Wellington spent his early army service as the lieutenant colonel of the 33rd Foot. After the Duke’s death, Queen Victoria permitted the 33rd to adopt the title ‘the Duke of Wellington’s Regiment’, a fitting attribution for one of the army’s most persistently successful regiments of foot.

- 79th Cameron Highlanders: As the French cavalry approached for the attack, the regiment formed square. Piper Mackay marched around the square playing the pibroch ‘Peace or War’. The King subsequently presented Mackay with silver mounted pipes as a reward.

- In spite of their presence in the film ‘Waterloo’, the 88th Foot, Connaught Rangers, was not present at Waterloo. They were on the far side of the Atlantic fighting the Americans.

- The 95th had three battalions at Waterloo. After the battle the regiment was given the title of the ‘Rifle Brigade’ in place of its number, which was reallocated to a newly raised infantry regiment.

- In the closing moments of the battle, a cannon ball struck the Earl of Uxbridge as he rode with the Duke of Wellington. The Duke said ‘By God you’ve lost your leg.’ The Earl said ‘By God, so I have.’ The remains of the leg were amputated in a house nearby and the owner of the house buried the leg in his garden, a place of interest for some years.

- Every year after 1815, the Duke of Wellington held a ‘Waterloo’ banquet for his officers. The banquet is still held.

- Umbrellas at the Battle of Waterloo: Captain Mercer of the British Horse Artillery described the miserable night he and his troop spent on the field of Waterloo before the battle: ‘My companion (the troop’s second captain) had an umbrella, which by the way afforded some merriment to our people on the march, this we planted against the sloping bank of the hedge, and seating ourselves under it, he on the one side of the stick, me on the other side, we lighted cigars and became-comfortable’.

- The Duke, usually indifferent to the way his officers chose to dress, drew the line at umbrellas. ‘At Bayonne, in December 1814,’ wrote Captain Gronow of the 1st Foot Guards, ‘His Grace, on looking round, saw, to his surprise, a great many umbrellas, with which the officers protected themselves from the rain that was then falling. Arthur Hill came galloping up to us saying, Lord Wellington does not approve of the use of umbrellas during the enemy’s firing, and will not allow the ‘gentlemen’s sons’ to make themselves ridiculous in the eyes of the army.’ Colonel Tynling, a few days afterwards, received a wigging from Lord Wellington for suffering his officers to carry umbrellas in the face of the enemy; His Lordship observing, ‘The Guards may in uniform, when on duty at St. James’, carry umbrellas if they please, but in the field it is not only ridiculous but unmilitary.’ Standing orders for the army in the Peninsular War and in the Waterloo campaign stated categorically ‘Umbrellas will not be opened in the presence of the enemy.’ However, the surgeon of Captain Mercer’s troop of Horse Artillery was seen to be sheltering under the forbidden item during the early part of the Battle of Waterloo.

- Between 1830 and 1838, Captain William Siborne, after extensive research with veterans from the battle, produced a model of the Battle of Waterloo as at 7pm on 17th June 1815. This model is in the National Army Museum in London.

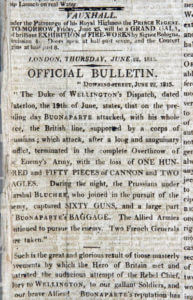

Official Bulletin in the Times newspaper dated 22nd June 1815 announcing the Battle of Waterloo fought on 18th June 1815

References for the Battle of Waterloo:

History of the British Army by John Fortescue Volume 10

British Battles on Land and Sea by James Grant Volume 2

A Near Run Thing by David Howarth

Wellington by S.G.P. Ward

The Waterloo Campaign: The German Victory by Peter Hofschröer

The Bloody Fields of Waterloo (account of the medical services at the battle and the circumstances of many individuals in the battle) by M.K.H. Crumplin

A Surgeon Artist at War: The Paintings of Sir Charles Bell by M.K.H. Crumplin and Captain P.H. Starling

Allied Order of Battle at the Battle of Waterloo:

The Duke of Wellington

Prince Willem of Orange

Lieutenant General Sir William Hill

Quartermaster General: Major General Sir George Murray

Adjutant General: Major General Sir Edward Barnes

The Cavalry: commanded by the Earl of Uxbridge:

Royal Horse Artillery:

Mercer’s Troop

Bull’s Troop

Ramsey’s Troop

The Rocket Troop

Household Brigade: Major General Lord Somerset

1st Life Guards

2nd Life Guards

Royal Horse Guards

King’s Dragoon Guards

Union Brigade: Major General Sir William Ponsonby

1st Royal Dragoons

2nd Dragoons, Royal Scots Greys

6th Inniskilling Dragoons

3rd Cavalry Brigade: Major General Dornberg

1st Light Dragoons, King’s German Legion

2nd Light Dragoons, King’s German Legion

23rd Light Dragoons (British)

4th Cavalry Brigade: Major General Sir John Vandeleur

11th Light Dragoons (British)

12th Light Dragoons (British)

16th Light Dragoons (British)

Lord Hill ordering the 13th Light Dragoons to attack at the Battle of Waterloo on 18th June 1815: picture by Harry Payne

5th Cavalry Brigade: Major General Grant

15th Hussars (British)

7th Hussars (British)

13th Light Dragoons (British)

6th Cavalry Brigade: Major General Sir Hussey Vivian

10th Hussars (British)

British Hussar Brigade attacks the French while the Duke of Wellington looks on at the Battle of Waterloo on 18th June 1815: picture by Denis Dighton

18th Hussars (British)

1st Hussars, King’s German Legion

7th Cavalry Brigade: Colonel Ahrentschildt

2nd Hussars, King’s German Legion

Netherlands Cavalry Division: commanded by Lieutenant General Baron de Collaert

Heavy Brigade: Major General Trip

1st Carabinier Regiment

2nd Carabinier Regiment

3rd Carabinier Regiment

1st Light Brigade: Major General Baron de Ghigny

4th Light Dragoon Regiment

8th Hussar Regiment

Hussar and Light Infantry of the Duke of Brunswick Oel’s Corps: Battle of Waterloo 18th June 1815: picture by Charles Hamilton Smith

2nd Light Brigade: Major General van Merlen

6th Hussar Regiment

4th Light Dragoon Regiment

Brunswick Cavalry:

2nd Hussar Regiment

Uhlans

Hannover Cavalry:

Duke of Cumberland Hussar Regiment

Infantry:

1st Foot Guards Division: commanded by Major General Cooke

1st Brigade: commanded by Major General Maitland

2nd Battalion 1st Foot Guards

3rd Battalion 1st Foot Guards

2nd Brigade: Major General Byng

2nd Battalion 2nd Coldstream Regiment of Foot Guards

2nd Battalion 3rd Foot Guards

2nd Division: commanded by Major General Sir Henry Clinton

3rd Brigade: commanded by Major General Adam

1st Battalion 52nd Light Infantry

1st Battalion 71st Highland Light Infantry

2nd Battalion 95th Rifles

1st Brigade, King’s German Legion: commanded by Colonel de Plat

1st Line Battalion, King’s German Legion

2nd Line Battalion, King’s German Legion

3rd Line Battalion, King’s German Legion

4th Line Battalion, King’s German Legion

3rd Hannover Brigade: commanded by Colonel Halkett

4 Landwehr battalions

3rd Division: commanded by Major General Alten

2nd Brigade, King’s German Legion: commanded by Colonel Baron Ompteda

5th Line Battalion, King’s German Legion

8th Line Battalion, King’s German Legion

1st Light Infantry, King’s German Legion

2nd Light Infantry, King’s German Legion

5th Brigade: commanded by Major General Sir Colin Halkett

2nd Battalion, 30th Foot

1st Battalion, 33rd Foot

2nd Battalion, 69th Foot

2nd Battalion, 73rd Foot

1st Hannover Brigade: commanded by Major General Kielmannsegge

2 Light Infantry Battalions

3 Battalions

Company of Jaegers

4th Division: commanded by Lieutenant General Colville

4th Brigade: commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Mitchell

1st Battalion, Royal Welch Fusiliers, 23rd Foot

3rd Battalion, 14th Foot

1st Battalion, 51st Light Infantry

5th Division: commanded by Lieutenant General Sir Thomas Picton

8th Brigade: commanded by Major General Kempt

1st Battalion, 28th Foot

1st Battalion, 32nd Foot

1st Battalion, 79th Highlanders

1st Battalion, 95th Rifles

9th Brigade: commanded by Major General Pack

2nd Battalion, 44th Foot

3rd Battalion, 1st Foot, the Royal Regiment

1st Battalion, 92nd Highlanders

1st Battalion, 42nd Highlanders

5th Hannover Brigade: commanded by Colonel von Vincke

Landwehr Battalion Hameln

Landwehr Battalion Gifhorn

Landwehr Battalion Hildesheim

Landwehr Battalion Peine

7th Queen’s Own Light Dragoons (Hussars): Battle of Waterloo 18th June 1815: picture by Charles Hamilton Smith

6th Division: commanded by Lieutenant General Sir Lowry Cole

10th Brigade: commanded by Major General Lambert

1st Battalion, 40th Foot

1st Battalion, 27th Foot

1st Battalion, 4th Foot, King’s Own Royal Regiment

4th Hannover Brigade: commanded by Colonel Best

Landwehr Battalion Osterode

Landwehr Battalion Minden

Landwehr Battalion Luneburg

Landwehr Battalion Verden

Brunswickers: commanded by Colonel Olferman

Jeager Battalion

Light Brigade:

Leib Light Infantry Battalion

1st Light Infantry Battalion

2nd Light Infantry Battalion

3rd Light Infantry Battalion

Line Brigade:

1st Line Battalion

2nd Line Battalion

3rd Line Battalion

Nassauers: commanded by Major General von Kruse

1st Battalion, 1st Line Infantry

2nd Battalion, 1st Line Infantry

Landwehr Infantry

2nd Netherlands Division: commanded by Lieutenant General Baron Perponcher-Sedlnitzky.

1st Brigade: commanded by Major General Graf van Bijlandt

7th (Belgian) Line Regiment

7th (Dutch) Militia

8th (Dutch) Militia

27th (Dutch) Jaeger Regiment

5th (Dutch) Militia

2nd Nassau Brigade: commanded by Major General Prince Bernard of Saxe-Weimar

3 battalions of the 2nd Nassau Regiment

2 battalions of the 28th Ober Nassau Regiment

Jaegers of the 28th Ober Nassau Regiment

3rd Netherlands Division: commanded by Lieutenant General Baron Chasse

1st Brigade: commanded by Colonel Detmers

35th (Belgian) Jaeger

2nd (Dutch) Line Regiment

4th (Dutch) Line Regiment

6th (Dutch) Line Regiment

19th (Dutch) Militia

2nd Brigade: commanded by Major General d’Aubreme

12th (Dutch) Line Regiment

13th (Dutch) Line Regiment

3rd (Dutch) Militia

10th (Dutch) Militia

3rd (Belgian) Jaeger

36th (Belgian) Jaeger

15. Podcast of the Battle of Waterloo: the battle fought on 18thJune 1815 that ended the dominance of the French Emperor Napoleon over Europe and saw the end of an epoch. John Mackenzie’s Britishbattles.com podcast.

15. Podcast of the Battle of Waterloo: the battle fought on 18thJune 1815 that ended the dominance of the French Emperor Napoleon over Europe and saw the end of an epoch. John Mackenzie’s Britishbattles.com podcast.

French Order of Battle at the Battle of Waterloo:

The Emperor Napoleon

Marshal Ney

Marshal Soult

Imperial Guard Corps: commanded by General Mortier

1st Division (Old Guard): commanded by General Friant

1st Grenadiers à Pied

2nd Grenadiers à Pied

1st Chasseurs à Pied

2nd Chasseurs à Pied

2nd Division (Middle Guard): commanded by General Morand

3rd Grenadiers à Pied

4th Grenadiers à Pied

3rd Chasseurs à Pied

4th Chasseurs à Pied

3rd Division (Young Guard): commanded by General Duhesme

1st Tirailleurs

3rd Tirailleurs

1st Voltigeurs

3rd Voltigeurs

Guard Cavalry:

Grenadiers à Cheval

Empress Dragoons

Chasseurs à cheval

Chevaux-legers lanciers

1st Corps: commanded by Marshall D’Erlon

Reserves:

7th Hussars

3rd Chasseurs à Cheval

3rd Lanciers

4th Lanciers

1st Division: commanded by General Allix

54th Regiment of the Line

55th Regiment of the Line

28th Regiment of the Line

105th Regiment of the Line

2nd Division: commanded by General Donzelot

13th Light Regiment

17th Regiment of the Line

19th Regiment of the Line

51st Regiment of the Line

3rd Division: commanded by General Marcognet

21st Regiment of the Line

46th Regiment of the Line

25th Regiment of the Line

45th Regiment of the Line

4th Division: commanded by General Durutte

8th Regiment of the Line

29th Regiment of the Line

85th Regiment of the Line

95th Regiment of the Line

2nd Corps: commanded by General Reille

Reserves:

1st Chasseurs à Cheval

6th Chasseurs à Cheval

5th Lancers

6th Lancers

5th Division: commanded by General Bachlu

2nd Light Regiment

61st Regiment of the Line

72nd Regiment of the Line

108th Regiment of the Line

Drummers and Fifers from various French Infantry Regiments: Battle of Waterloo on 18th June 1815: picture by Suhrs

6th Division: commanded by General Prince Jerome Bonaparte

1st Light Regiment

3rd Regiment of the Line

1st Regiment of the Line

2nd Regiment of the Line

7th Division commanded by General Girard

11th Light Regiment

82nd Regiment of the Line

12th Light Regiment

4th Regiment of the Line

9th Division: commanded by General Foy

92nd Regiment of the Line

93rd Regiment of the Line

100th Regiment of the Line

4th Light Regiment

Drum Majors from the 4th and 2nd of the Line : Battle of Waterloo on 18th June 1815: picture by Suhrs

3rd Corps: commanded by General Vandamme

Reserves:

4th Chasseurs à Cheval

9th Chasseurs à Cheval

12th Chasseurs à Cheval

8th Division: commanded by General Lefol

15th Light Regiment

23rd Regiment of the Line

37th Regiment of the Line

64th Regiment of the Line

10th Division: commanded by General Habert

11th Regiment of the Line

34th Regiment of the Line

22nd Regiment of the Line

77th Regiment of the Line

2nd Swiss Infantry

Cuirassiers and Trumpeter of the 1st Cuirassier Regiment: Battle of Waterloo on 18th June 1815: picture by Suhrs

11th Division: commanded by General Berthezène

12th Regiment of the Line

56th Regiment of the Line

33rd Regiment of the Line

86th Regiment of the Line

6th Corps: commanded by General Mouton

19th Division: commanded by General Zimmer

5th Regiment of the Line

11th Regiment of the Line

27th Regiment of the Line

84th Regiment of the Line

20th Division: commanded by General Jeannin

5th Light Regiment

10th Regiment of the Line

47th Regiment of the Line

107th Regiment of the Line

21st Division: commanded by General Teste

8th Light Regiment

40th Regiment of the Line

65th Regiment of the Line

75th Regiment of the Line

1st Cavalry Corps: commanded by General Pajol

Division Subervie:

1st Lancers

2nd Lancers

11th Chasseurs à Cheval

3rd Cavalry Corps: commanded by General Kellerman

Division L’Heritier:

2nd Cuirassiers

7th Dragoons

8th Cuirassiers

11th Cuirassiers

Division d’Hurbal:

1st Carabiniers

2nd Carabiniers

2nd Cuirassiers

3rd Cuirassiers

4th Cavalry Corps: commanded by General Milhaud

Division Wathier:

1st Cuirassiers

4th Cuirassiers

7th Cuirassiers

Division Delort:

5th Cuirassiers

10th Cuirassiers

6th Cuirassiers

British regimental casualties:

1st Life Guards 6 officers and 72 men killed and wounded

2nd Life Guards 1 officer and 46 men killed and wounded

Trooper of the Royal Dragoons suffering from a sabre cut: Battle of Waterloo on 18th June 1815: picture by Sir Charles Bell the surgeon who treated the soldier

Royal Horse Guards 5 officers and 80 men killed and wounded

King’s Dragoon Guards 7 officers and 140 men killed and wounded

Royal Dragoons 13 officers and 173 men killed and wounded

Royal Scots Greys 2nd Dragoons 11 officers and 185 men killed and wounded

6th Inniskilling Dragoons 6 officers and 183 men killed and wounded

7th Hussars 7 officers and 179 men killed and wounded

10th Hussars 7 officers and 60 men killed and wounded

11th Hussars 5 officers and 45 men killed and wounded

12th Light Dragoons 6 officers and 106 men killed and wounded

13th Light Dragoons 10 officers and 80 men killed and wounded

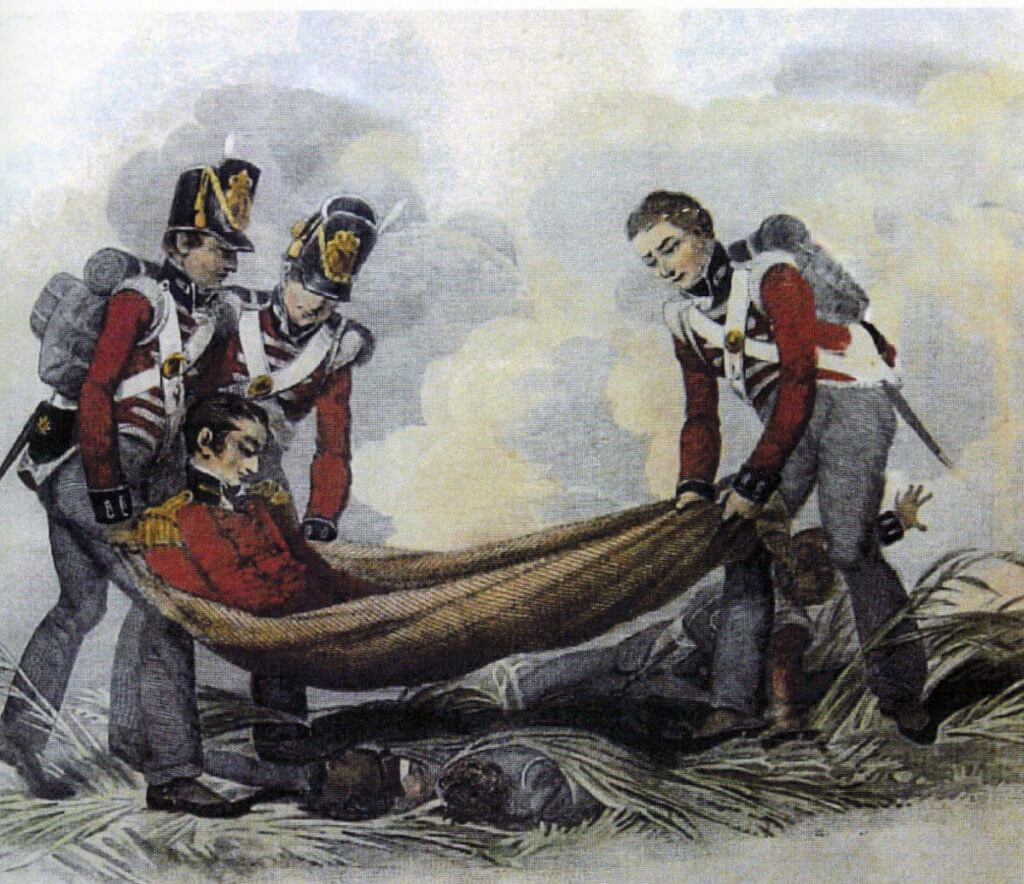

Fatally wounded Colonel Sir Alexander Gordon carried from the field at the Battle of Waterloo on 18th June 1815

15th Light Dragoons 5 officers and 69 men killed and wounded

16th Light Dragoons 5 officers and 36 men killed and wounded

18th Light Dragoons 2 officers and 83 men killed and wounded

Royal Artillery 29 officers and 265 men killed and wounded

Royal Engineers 0 officers and 0 men killed and wounded

1st Foot Guards (two battalions) 15 officers and 472 men killed and wounded

2nd Coldstream Guards 8 officers and 296 men killed and wounded

3rd Foot Guards 12 officers and 327 men killed and wounded

1st Foot 15 officers and 128 men killed and wounded

Surgeon Francis Burton of the 4th King’s Own Regiment amputating in the field at the Battle of Waterloo on 18th June 1815: picture by Jason Askew

4th King’s Own Regiment of Foot 8 officers and 125 men killed and wounded

14th Foot 1 officers and 28 men killed and wounded

Sergeant Anthony Tuttmeyer 2nd KGL left arm shattered by a shell: Battle of Waterloo on 18th June 1815: picture by Sir Charles Bell the surgeon who treated the soldier

23rd Royal Welch Fusiliers 10 officers and 89 men killed and wounded

27th Foot, 15 officers and 463 men killed and wounded

28th Foot 16 officers and 161 men killed and wounded

30th Foot 18 officers and 207 men killed and wounded

32nd Foot 9 officers and 165 men killed and wounded

33rd Foot 11 officers and 128 men killed and wounded

40th Foot 12 officers and 189 men killed and wounded

42nd Highlanders 6 officers and 44 men killed and wounded

44th Foot 4 officers and 61 men killed and wounded

51st Light Infantry 2 officers and 29 men killed and wounded

52nd Light Infantry 9 officers and 190 men killed and wounded

69th Foot 6 officers and 67 men killed and wounded

71st Highland Light Infantry 16 officers and 184 men killed and wounded

73rd Highlanders 6 officers and 225 men killed and wounded

79th Highlanders 13 officers and 171 men killed and wounded

92nd Highlanders 6 officers and 110 men killed and wounded

95th Rifles (three battalions) 30 officers and 396 men killed and wounded

The previous battle of the Napoleonic Wars is the Battle of Quatre Bras

The next battle in the British Battles series is the Battle of Ghuznee

References for the Battle of Waterloo:

History of the British Army by John Fortescue Volume 10

British Battles on Land and Sea by James Grant Volume 2

Wellington: The Road to the Lion’s Mound 1769-1815 by Daniel Res

A Near Run Thing by David Howarth

Wellington by S.G.P. Ward

The Waterloo Campaign: The German Victory by Peter Hofschröer

The Bloody Fields of Waterloo (account of the medical services at the battle and the circumstances of many individuals in the battle) by M.K.H. Crumplin

A Surgeon Artist at War: The Paintings of Sir Charles Bell by M.K.H. Crumplin and Captain P.H. Starling

15. Podcast of the Battle of Waterloo: the battle fought on 18thJune 1815 that ended the dominance of the French Emperor Napoleon over Europe and saw the end of an epoch. John Mackenzie’s Britishbattles.com podcast.