Nelson’s crushing defeat of the French and Spanish Navies on 21st October 1805, establishing Britain as the dominant world naval power for a century, but at the cost of Nelson’s life

The previous battle of the Napoleonic Wars is the Battle of Copenhagen

The next battle of the Napoleonic Wars is the Battle of Maida

War: Napoleonic

Date of the Battle of Trafalgar: 21st October 1805

Place of the Battle of Trafalgar: At Cape Trafalgar off the South-Western coast of Spain, south of Cadiz.

Combatants at the Battle of Trafalgar: The British Royal Navy against the Fleets of France and Spain.

Commanders at the Battle of Trafalgar: Admiral Viscount Lord Nelson and Vice Admiral Collingwood against Admiral Villeneuve of France and Admirals d’Aliva and Cisternas of Spain.

Admiral Villeneuve French commander at the Battle of Trafalgar on 21st October 1805 during the Napoleonic Wars

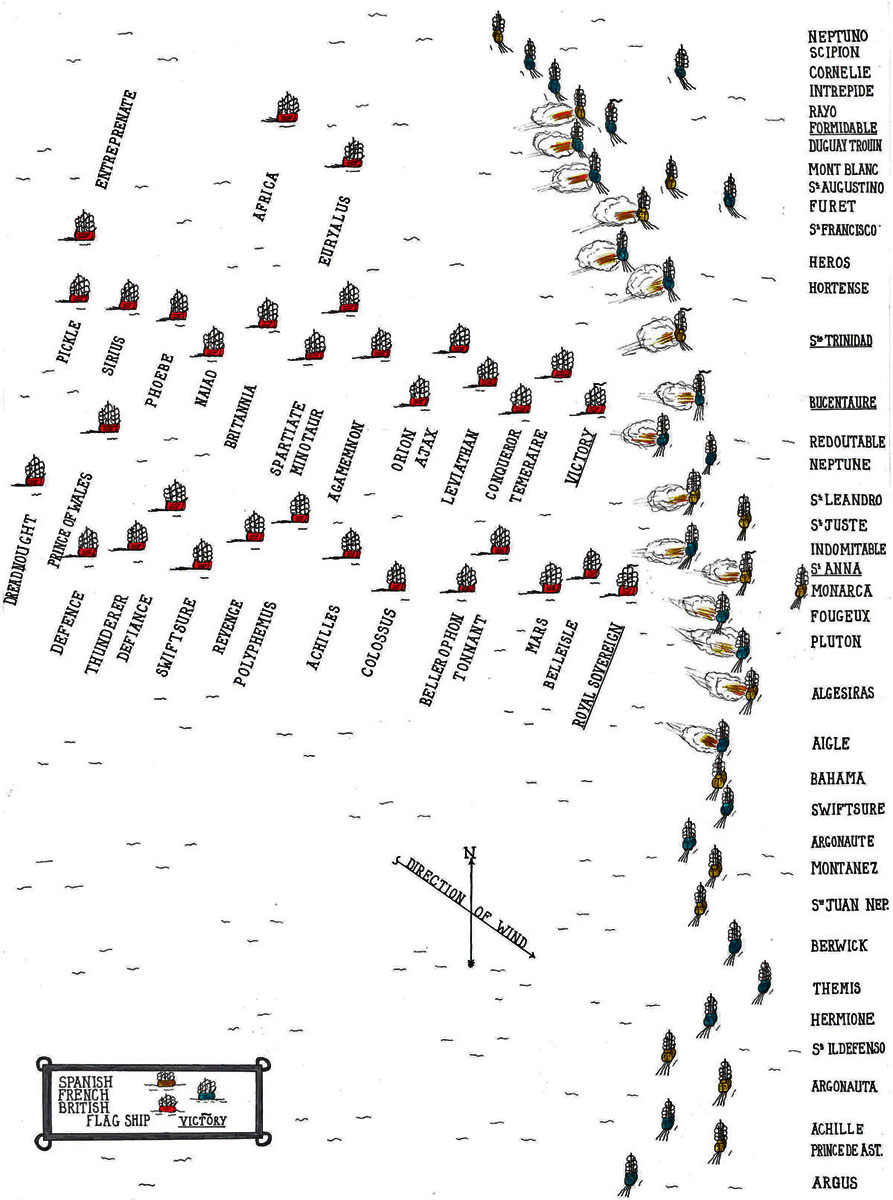

Size of the fleets at the Battle of Trafalgar: 32 British ships (25 ships of the line, 4 Frigates and smaller craft), 23 French ships and 15 Spanish ships (33 ships of the line, 7 Frigates and smaller craft). 4,000 troops, including riflemen from the Tyrol, were posted in small detachments through the French and Spanish Fleets.

Winner of the Battle of Trafalgar: Resoundingly, the Royal Navy.

British Ships at the Battle of Trafalgar (name of captain and number of guns):

Vice Admiral Cuthbert Collingwood commander of the British Leeward Squadron at the Battle of Trafalgar on 21st October 1805 during the Napoleonic Wars: picture by Henry Howard

Admiral Lord Nelson’s Division: HMS Victory (Flagship of Admiral Lord Nelson: Captain Thomas Hardy, 104), Temeraire (Captain Eliab Harvey, 98), Neptune (Captain Thomas Fremantle, 98), Conqueror (Captain Israel Pellew, 74), Leviathan (Captain Henry Bayntun, 74), Ajax (Lieutenant John Pilford, 74), Orion (Captain Edward Codrington, 74), Agamemnon (Captain Sir Edward Bury, 64), Minotaur (Captain Charles Mansfield, 74), Spartiate (Captain Sir Francis Laforey, 74), Euryalus (Captain Henry Blackwood, 36), Britannia (Flagship of Rear Admiral Lord Northesk: Captain Charles Bullen, 100), Africa (Captain Henry Digby, 64), Naiad (Captain Thomas Dundas, 38), Phoebe (Captain Thomas Capel, 36), Entreprenante (Lieutenant Robert Young, 10), Sirius (Captain William Prowse, 36) and Pickle (Lieutenant John La Penotière, 6).

Vice Admiral Collingwood’s Division: HMS Royal Sovereign (Flagship of Vice Admiral Cuthbert Collingwood: Captain Edward Rotheram, 100), Belleisle (Captain William Hargood, 74), Mars (Captain George Duff, 74), Tonnant (Captain Charles Tyler, 80), Bellerophon (Captain John Cooke, 74), Colossus (Captain James Morris, 74), Achilles (Captain Richard King, 74), Polyphemus (Captain Robert Redmill, 64), Revenge (Captain Robert Moorsom, 74), Swiftsure (Captain William Rutherford, 74), Defiance (Captain Philip Durham, 74), Thunderer (Lieutenant John Stockham, 74), Prince of Wales (Captain Richard Grindall, 98), Dreadnought (Captain John Conn, 98) and Defence (Captain George Hope, 74).

French Ships at the Battle of Trafalgar (name of captain and number of guns): Bucentaure (Flagship of Vice Admiral Villeneuve: Captain Magendie, 80), Formidable (Flagship of Rear Admiral Le Pelley: Captain Letellier, 80), Scipion (Captain Berrenger, 74), Intrépide (Captain Infernet, 74), Cornélie (Captain Martineng, 40), Duguay Truin (Captain Touffet, 74), Mont Blanc (Captain Lavillegris, 74), Heros (Commander Poulain, 74), Hortense (Captain Lamellerie, 40), Neptune (Commodore Maistral, 80), Redoutable (Captain Lucas, 74), Indomptable (Captain Hubert, 80), Fougueux (Captain Baudoin, 74), Pluton (Captain Cosmao-Kerjulien, 74), Aigle (Captain Gourrège, 74), Swiftsure (Captain L’Hospitalier, 74), Argonaute (Captain Épron-Desjardins, 74), Berwick (Captain de Camas, 74), Hermione (Captain Mahé, 40), Thémis (Captain Jugan, 40), Achille (Captain Deniéport, 74) Rhin (Captain Chesneau, 40), Furet (Lieutenant Dumay, 18) and Argus (Lieutenant Taillard, 16).

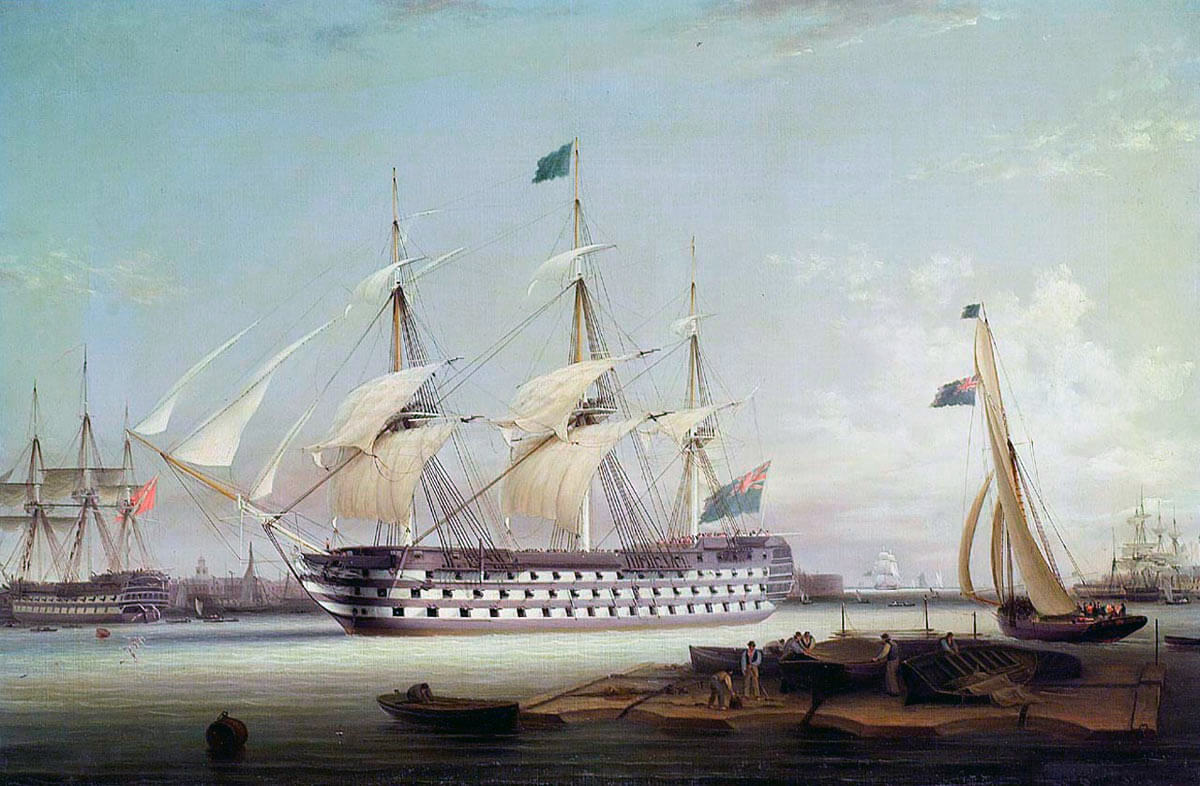

HMS Victory at sea: Battle of Trafalgar on 21st October 1805 during the Napoleonic Wars: picture by Monamy Swaine

Spanish Ships at the Battle of Trafalgar (name of captain and number of guns): Santa Anna (Flagship of Vice Admiral de Alava: Captain de Gardoqui, 112), Santissima Trinidad (Flagship of Rear Admiral de Cisneros: Captain de Uriarte, 136), Neptuno (Captain Flores, 80), Rayo (Captain MacDonnell, 100), San Augustin (Captain Cagigal, 74), San Francisco d’Assisi (Captain Flores, 74), San Leandro (Captain Quevedo, 64), San Justo (Captain Gaston, 74), Monarca (Captain Argumosa, 74), San Ildefenso (Captain Vargas, 74), Algeciras (Flagship of Rear Admiral Magon: Commander Tourneur, 74), Bahama (Commodore Galiano, 74), Montanes (Captain Bustamente, 74), San Juan Nepomucano (Commodore Elorza, 74), Argonauta (Captain Pareja, 80) and Prince de Asturias (Flagship of Admiral Gravina: Commodore Hore, 112).

HMS Britannia entering Portsmouth Harbour: Battle of Trafalgar on 21st October 1805 during the Napoleonic Wars: picture by Robert Strickland Thomas

Ships and Armaments at the Battle of Trafalgar: Sailing warships of the 18th and 19th Century carried their main armaments in broadside batteries along the sides. Ships were classified according to the number of guns carried or the number of decks carrying batteries.

At the Battle of Trafalgar, Nelson’s main force comprised 8 three decker battleships carrying more than 90 guns each. The enormous Spanish ship Santissima Trinidad carried 120 guns and the Santa Anna 112 guns.

Gun on a Royal Navy ship in action: Battle of Trafalgar on 21st October 1805 during the Napoleonic Wars

The size of gun on the line of battle ships was up to 24 pounder, firing heavy iron balls, or chain and link shot designed to wreck rigging. Trafalgar was a close fleet action. Ships manoeuvred up to the enemy and delivered broadsides at a range of a few yards. To take full advantage of the close range, guns were ‘double shotted’ with grape shot on top of ball. It is said that the crews in some French ships were unable to face this appalling ordeal, closing their gun ports and attempting to escape the fire.

Collingwood’s Royal Sovereign fired its first broadside at the Battle of Trafalgar into the stern of the Spanish ship Santa Anna causing her massive damage.

The discharge of guns at close range easily set fire to an opposing vessel. Fires were difficult to control in battle and several ships were destroyed in this way, notably the French ship Achille.

Ships carried a variety of smaller weapons on the top deck and in the rigging, from swivel guns firing grape shot or canister (bags of musket balls) to hand held muskets and pistols, each crew seeking to annihilate the enemy officers and sailors on deck.

British captains expected their ships to clear for action in 10 minutes. Cabin walls were dismantled; gun crews formed up; the gunner and his mates opened the magazine and distributed ammunition to the guns; decks were wetted and sprinkled with sand; the surgeon laid out his implements in the cockpit; the marines assembled to take post on the decks or in the rigging. The final act of preparation was for the gun ports to be opened and the guns run out, the truck wheels rumbling through the ship.

The discharge of guns at close range easily set fire to an opposing vessel. Fires were difficult to control in battle and several ships were destroyed in this way, notably the French ship Achille.

Death of Nelson at the Battle of Trafalgar on 21st October 1805 during the Napoleonic Wars: picture by Henri Dupray

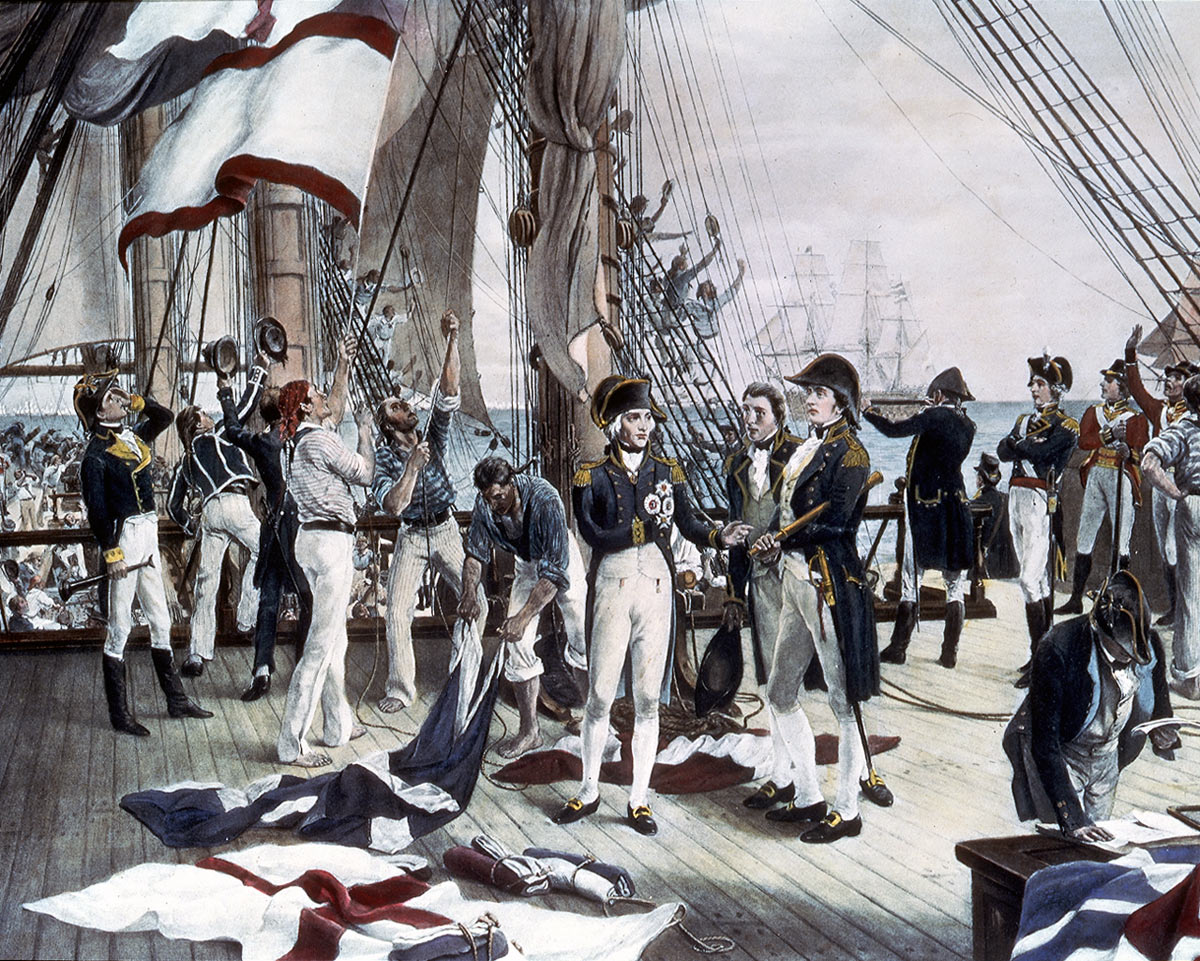

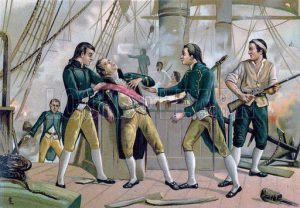

The aim in battle was to lock ships together and capture the enemy by boarding. Savage hand to hand fighting took place at Trafalgar on several ships. The crew of the French Redoutable, living up to the name of their ship, boarded Victory but were annihilated in the brutal struggle on Victory’s top deck.

Crew of the French ship Redoutable boarding Victory during the Battle of Trafalgar on 21st October 1805 during the Napoleonic Wars: picture by E.S. Hodgson

Wounds in Eighteenth Century naval fighting were terrible. Cannon balls ripped off limbs or, striking wooden decks and bulwarks, drove splinter fragments across the ship causing horrific wounds. Falling masts and rigging inflicted crush injuries. Sailors stationed aloft fell into the sea from collapsing masts and rigging to be drowned. Heavy losses were caused when a ship finally succumbed.

Unexpected member of a French crew rescued at the Battle of Trafalgar on 21st October 1805 during the Napoleonic Wars

Ships’ crews of all nations were tough. The British, with continual blockade service against the French and Spanish, were well drilled. British gun crews could fire three broadsides or more to every two fired by the French and Spanish.

The British officers were hard bitten and experienced. A young officer joining the Royal Navy in 1789, when the French Wars began, would have served for 16 years of warfare by the time of the Battle of Trafalgar, much of it continuously at sea.

View from HMS Victory’s Mizzen Starboard Shrouds at the Battle of Trafalgar on 21st October 1805 during the Napoleonic Wars: picture by Joseph Mallord William Turner

British captains were responsible for recruiting their ship’s crew. Men were taken wherever they could be found, largely by means of the press gang. All nationalities served on British ships including French and Spanish. Loyalty for a crew lay primarily with their ship. Once the heat of battle subsided there was little animosity against the enemy. Great efforts were made by British crews to rescue the sailors of foundering French and Spanish ships at the end of the battle.

HMS Victory flanked by Euryalus and Temeraire heading for the French and Spanish line at the Battle of Trafalgar on 21st October 1805 during the Napoleonic Wars: picture by Thomas Whitcombe

Life on a warship, particularly the large ships of the line, was crowded and hard. Discipline was enforced with extreme violence, small infractions punished with public lashings. The food, far from good, deteriorated as ships spent time at sea. Drinking water was in constant short supply and usually brackish. Shortage of citrus fruit and fresh vegetables meant that scurvy easily and quickly set in. The great weight of guns and equipment and the necessity to climb rigging in adverse weather conditions frequently caused serious injury.

Above all, a life spent carrying out blockade duty was monotonous in the extreme. The prospect of a decisive battle against the French and Spanish put the British Fleet in a state of high excitement.

Account of the Battle of Trafalgar:

In July 1805, the French Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte secretly left Milan and hurried to Boulogne in France, where his Grande Armée waited in camp to cross the English Channel and invade England.

French ship Redoutable dismasted and sinking at the Battle of Trafalgar on 21st October 1805 during the Napoleonic Wars: picture by Auguste Mayer

Napoleon only needed Admiral Villeneuve to bring the joint French and Spanish Fleet from South Western Spain into the Channel, for the invasion of England to take place.

The First Sea Lord in London appointed Admiral Lord Nelson Commander in Chief of the British Fleet, assembling to attack the French and Spanish ships.

Nelson on the deck of HMS Victory at the Battle of Trafalgar on 21st October 1805 during the Napoleonic Wars: picture by William Heysham Overend

Admiral Nelson selected His Majesty’s Ship Victory as his flagship and sailed south towards Gibraltar. As the British ships intended for his Fleet were made ready, they sailed south to join Nelson.

In October 1805, the French Admiral Villeneuve, the commander of the joint French/Spanish Fleet was still in harbour at Cadiz. Villeneuve received a stinging rebuke from Napoleon, accusing him of cowardice, and Villeneuve steeled himself to leave harbour and make for the Channel.

Battle of Trafalgar on 21st October 1805 during the Napoleonic Wars: picture by William Clarkson Stanfield

Villeneuve was encouraged in his resolve to sail north, by the belief that there was no strong British Fleet nearby and that Nelson was still in England. Leaving picket frigates to watch Cadiz harbour, Nelson kept his main fleet well out to sea.

Death of the Spanish Admiral Gravina aboard Prince de Asturias at the Battle of Trafalgar on 21st October 1805 during the Napoleonic Wars

On 19th October 1805 at 9am, HMS Mars relayed the signal received from the British frigates that the Franco-Spanish Fleet was emerging from Cadiz.

At dawn on 21st October 1805, with a light wind from the west, Nelson signalled his fleet to begin the attack.

The British captains understood fully what was required of them. Nelson had explained his tactics repeatedly over the previous weeks, until every ship’s captain knew his role.

At 6.40am on 21st October 1805, the British Fleet beat to quarters and the ships cleared for action: cooking fires were thrown overboard, the movable bulwarks stored, the decks sanded and ammunition carried to each gun. The gun crews took their positions. The Royal Marines lined the decks and rigging.

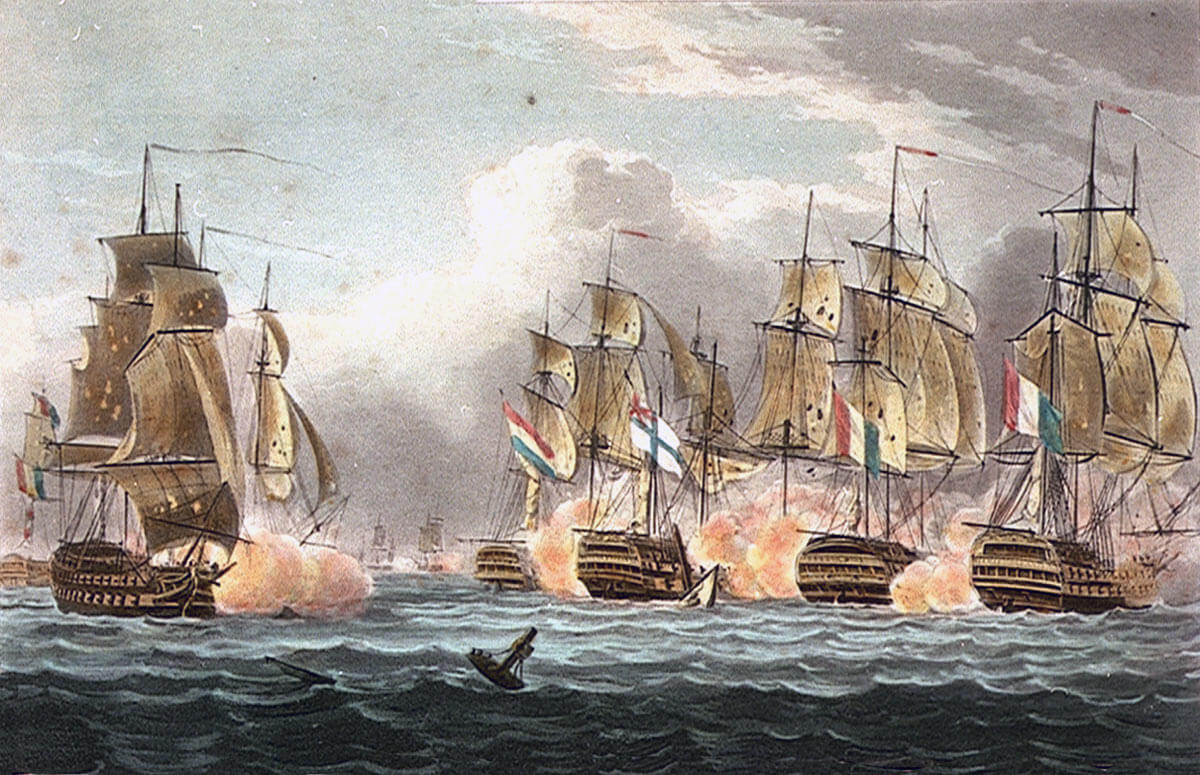

The French and Spanish Fleets were sailing in line ahead in an arc like formation. The British Fleet attacked in two squadrons in line ahead; the Windward Squadron, led by Nelson in Victory, and the Leeward (southern or right squadron), headed by Collingwood in Royal Sovereign; the ships of the Fleet were divided between the two squadrons.

Nelson aimed to cut the Franco-Spanish Fleet at a point one third along the line, with Collingwood attacking the rear section. In the light wind, the van of the Franco-Spanish Fleet would be unable to turn back and take part in the battle, until too late to help their comrades, leaving the section of the Franco-Spanish Fleet under attack heavily outnumbered.

Nelson seems to have been entirely confident of success. He told his Flag Captain, Hardy, he expected to take twenty of the enemy’s ships. He was also convinced of his impending death in the battle. Nelson told his friend Blackwood, the captain of the Euryalus, when he came on board Victory before the battle, ‘God bless you, Blackwood. I shall never see you again.’ Nelson wore dress uniform with his decorations, a conspicuous figure on the deck of the Victory.

HMS Bellerophon (ship in centre) at the moment of the death of Captain Cook at the Battle of Trafalgar on 21st October 1805 during the Napoleonic Wars

In his long and eventful naval career, Nelson had lost his right arm and his right eye. Perhaps, like Wolfe at Quebec, Nelson preferred to die at the moment of supreme victory, rather than live on in a disabled state.

The two British squadrons, led by the Flagships, sailed towards the Franco-Spanish line, Collingwood’s Royal Sovereign significantly ahead of Victory. Anxious that the admiral should not be excessively exposed to enemy fire, the captain of Temeraire attempted to overtake Victory, but was ordered back into line by Nelson.

Battle of Trafalgar on 21st October 1805 during the Napoleonic Wars: picture by William Lionel Wyllie

The first broadside was fired by the French ship Fougueux into Royal Sovereign, as Collingwood burst through the Franco-Spanish line. Royal Sovereign held her fire until she sailed past the stern of the Spanish Flagship, Santa Anna. Royal Sovereign raked Santa Anna with double-shotted fire, a broadside that is said to have disabled 400 of her crew and 14 guns.

Royal Sovereign swung round onto Santa Anna’s beam and the two ships exchanged broadsides. The ships following in the Franco-Spanish line joined in, attacking Collingwood; Fougueux, San Leandro, San Justo and Indomptable, until driven off by the rest of the Leeward Squadron as they came up. Royal Sovereign forced Santa Anna to surrender, when both ships were little more than wrecks.

Battle of Trafalgar on 21st October 1805 during the Napoleonic Wars: picture by William Clarkson Stanfield

Victory led the Windward Squadron towards a point in the line between Redoutable and Bucentaure. The Franco-Spanish Fleet at this point was too crowded for there to be a way through, and the Victory simply rammed the Redoutable, firing one broadside into her and others into the French Flagship, Bucentaure, and the Spanish Flagship, Santissima Trinidad. The British ship Temeraire flanked Redoutable on the far side and a further French ship linked to Temeraire, all firing broadsides at point blank range.

The following ships of Nelson’s squadron, as they came up, engaged the other ships in the centre of the Franco-Spanish line. The leading Franco-Spanish squadron continued on its course away from the battle, until peremptorily ordered to return by Villeneuve.

HMS Victory in action at the Battle of Trafalgar on 21st October 1805 during the Napoleonic Wars: picture by Joseph Mallord William Turner

During the fight with Redoutable, the soldiers and sailors in the French rigging fired at men exposed on the Victory’s decks. A musket shot hit Nelson, knocking him to the deck and breaking his back. The admiral was carried below to the midshipmen’s berth, where he constantly asked after the progress of the battle. Eventually Hardy, Victory’s captain, was able to tell Nelson, before he died, that the Fleet had captured fifteen of the enemy’s ships. Nelson knew he had won a substantial victory.

‘Fall of Nelson’ at the Battle of Trafalgar on 21st October 1805 during the Napoleonic Wars: picture by Denis Dighton

The battle reached its climax in the hour after Nelson’s injury. Neptune, Leviathan and Conqueror, as they came up, battered Villeneuve’s Flagship Bucentaure into submission, and took the surrender of the French admiral. Temeraire, while fighting with the Redoutable, fired a crippling broadside into the Fougueux. Leviathan engaged the San Augustino, bringing down her masts and boarding her.

In the Leeward Squadron, Belleisle was stricken into a wreck by Achille and the French Neptune, until relieved by the British Swiftsure. Achille was then battered by broadsides, until fires reached her magazine and she blew up.

Ships in action (Bucentaure and Temeraire) at the Battle of Trafalgar on 21st October 1805 during the Napoleonic Wars: picture by Auguste Mayer

All the French and Spanish ships of that part of the line were destroyed, captured or fled: of the 19 French and Spanish ships, 11 were captured or burnt, while 8 fled to leeward. Many of these ships fought hard. Argonauta and Bahama lost 400 of their crews each. San Juan Nepomuceno lost 350. When she blew up, Achille had lost all her officers, other than a single midshipman. The resistance of the French ship Redoutable was in keeping with her name.

The Franco-Spanish van, commanded by Admiral Dumanoir, passed the battle, firing broadsides indiscriminately into comrade and enemy, and returned to Cadiz.

Taking of the French ship Duguay Trouin at the end of the Battle of Trafalgar on 21st October 1805 during the Napoleonic Wars: picture by Charles Edward Dixon

Casualties at the Battle of Trafalgar: British casualties were 1,587 men killed and wounded. The French and Spanish casualties were never revealed, but are thought to have been around 16,000 men killed, wounded or captured.

Destruction of the French ship Achille at the end of the Battle of Trafalgar on 21st October 1805 during the Napoleonic Wars: picture by Richard Brydges Beechey

Follow-up to the Battle of Trafalgar: Following the battle, a storm blew up, wrecking many of the ships damaged in the action. Of those captured, only four survived to be brought into Gibraltar.

The consequences of the battle were far reaching. Napoleon’s plan to invade Britain was thwarted. He broke up the camp at Boulogne and marched to Austria, where he won the great victory of Austerlitz against the Austrians and Russians.

French ships scattered in the storm that followed the Battle of Trafalgar on 21st October 1805 during the Napoleonic Wars

The victory at the Battle of Trafalgar ensured that Britain’s dominance at sea remained largely unchallenged for the rest of the ten years of war against France, and continued worldwide for a further one hundred and twenty years.

Admiral Villeneuve was taken a prisoner to England. On his release, Villeneuve travelled back to France, but died violently on the journey to Paris.

Lord Nelson’s body was brought to England and the admiral given a state funeral. Nelson’s body is entombed in St Paul’s cathedral in London.

George Perceval’s Naval General Service Medal 1847 with clasp for the Battle of Trafalgar on 21st October 1805 during the Napoleonic Wars

Medals for the Battle of Trafalgar:

The Naval General Service Medal 1848 was issued to all those serving in the Royal Navy in specified actions during the period 1793 to 1840 and applied for the medal. The medal was only issued to those entitled to one of the 231 clasps.

The Battle of Trafalgar was such a clasp for the medal.

One of those awarded the Naval General Service Medal 1848 was George Perceval, who left Harrow School to serve in the Royal Navy as a powder monkey on HMS Orion.

Medals were also struck privately to commemorate the Battle of Trafalgar.

The Birmingham industrialist Matthew Boulton caused a white metal medal to be produced and awarded to those who served at the Battle of Trafalgar on British ships.

Anecdotes and traditions from the Battle of Trafalgar:

- As the British Fleet bore down on the Franco-Spanish line, Nelson directed Lieutenant Pascoe, the signals officer of Victory, to send the signal to the Fleet ‘Nelson confides every man will do his duty.’ Captain Hardy and Pascoe suggested this be changed to ‘England expects every man will do his duty’. Nelson agreed. As the signal ran up Victory’s halyard, the Fleet burst into cheers. Nelson followed this with his standard battle signal ‘Engage the enemy more closely’.

- Nelson was a remarkable man. He combined a gentleness of character with an extreme ruthless aggression in action. This characteristic, combined with his technical brilliance at sea, made him an invincible enemy. Nelson’s tactic at Trafalgar was simple but devastatingly effective. Nelson was widely feared. If Villeneuve had known that the British admiral was present outside Cadiz harbour, it seems unlikely that even the scathing messages from Napoleon would have enticed him to sea. An American captain sailing into Cadiz assured the French admiral that Nelson was still in London.

- Nelson default instruction to his officers was ‘No captain can do wrong if he puts his ship alongside the nearest enemy’.

- HMS Victory, Nelson’s Flagship at the Battle of Trafalgar, lies in Portsmouth Harbour, preserved as it was at the time of the battle.

- In his final letter, Nelson asked that the Nation look after his mistress, Lady Emma Hamilton, and their daughter, Horatia. Nelson’s brother was ennobled and Nelson’s wife awarded a pension. Nothing was done for Lady Hamilton. She died in reduced circumstances in Calais in 1815.

- The naming of the warships: Many of the Spanish ships carried religious titles: Santa Anna, Santissima Trinidad, Sant Juan Nepomuceno. Classical labels were popular with the British and French: Mars, Ajax, Agamemnon, Minotaur (British); Scipion, Pluton, Hermione, Argus, Neptune (French). There were Swiftsures and Achilles in the British and French Fleets. The French had an Argonaute and the Spanish an Argonauta. Three British ships held French names: Belleisle, Tonnant and Bellerophon, marking that these ships or their predecessors had been captured from France. The French took names from heroic characteristics: Redoutable, Indomitable, Intrépide. Two British names reflected great size: Colossus, Leviathan. All three navies possessed a ship named after the classical god Neptune.

HMS Belleisle after the Battle of Trafalgar on 21st October 1805 during the Napoleonic Wars: picture by William Lionel Wyllie

References for the Battle of Trafalgar:

The Royal Navy, a History by Sir W. Laird Clowes

Life of Nelson by Robert Southey

Nelson by Carola Oman

Nelson’s death on HMS Victory at the Battle of Trafalgar on 21st October 1805 during the Napoleonic Wars: picture by Arthur William Devis

British Battles on Land and Sea edited by Sir Evelyn Wood

British Battles by Grant

The previous battle of the Napoleonic Wars is the Battle of Copenhagen

The next battle of the Napoleonic Wars is the Battle of Maida