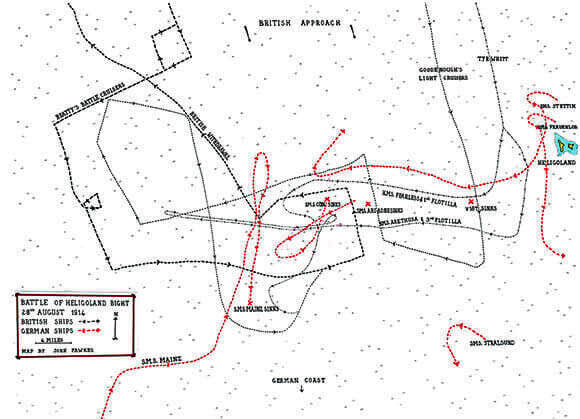

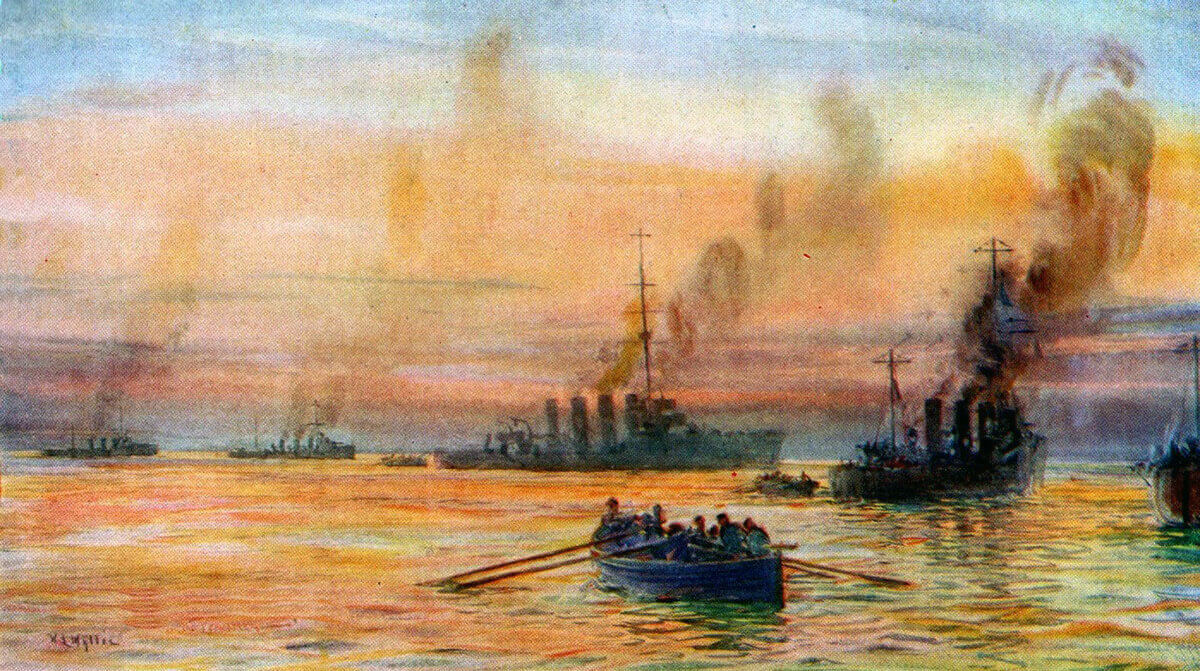

The first naval encounter of the First World War, on 28th August 1914, between the British and German fleets, in the North Sea off the North German coast

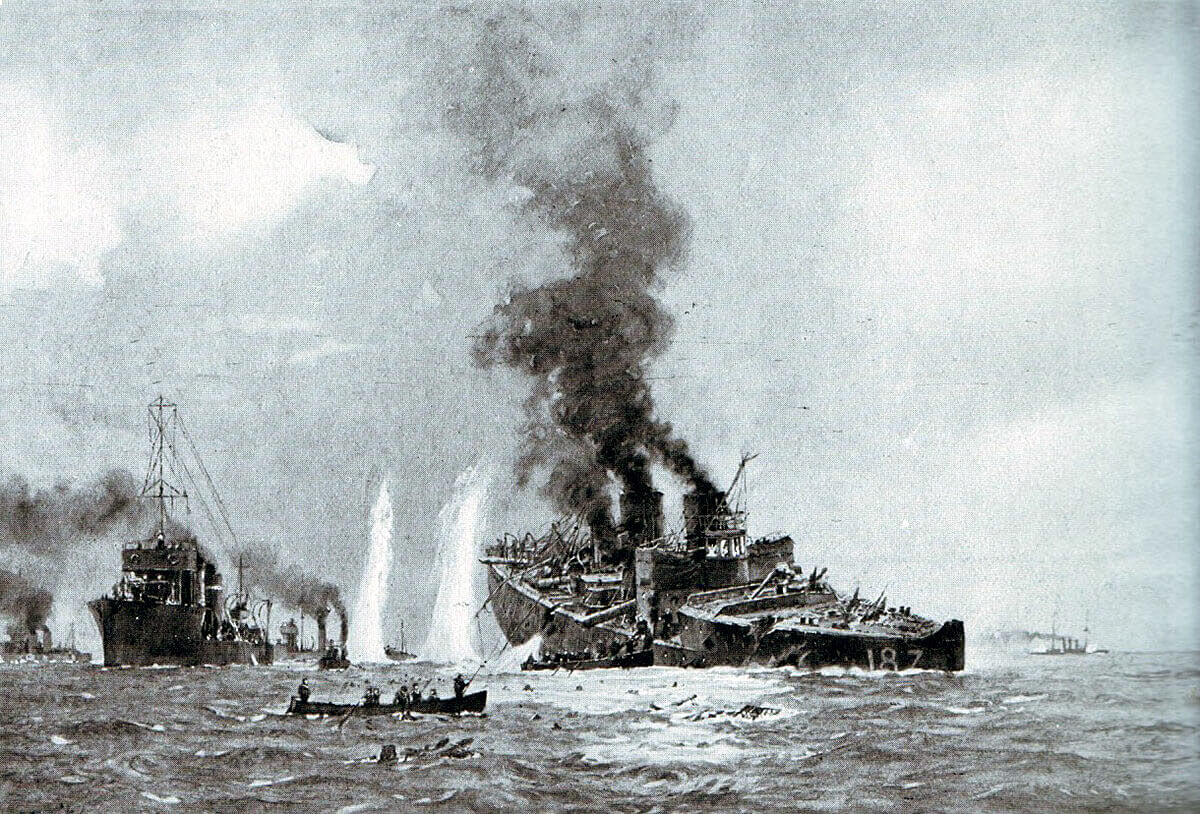

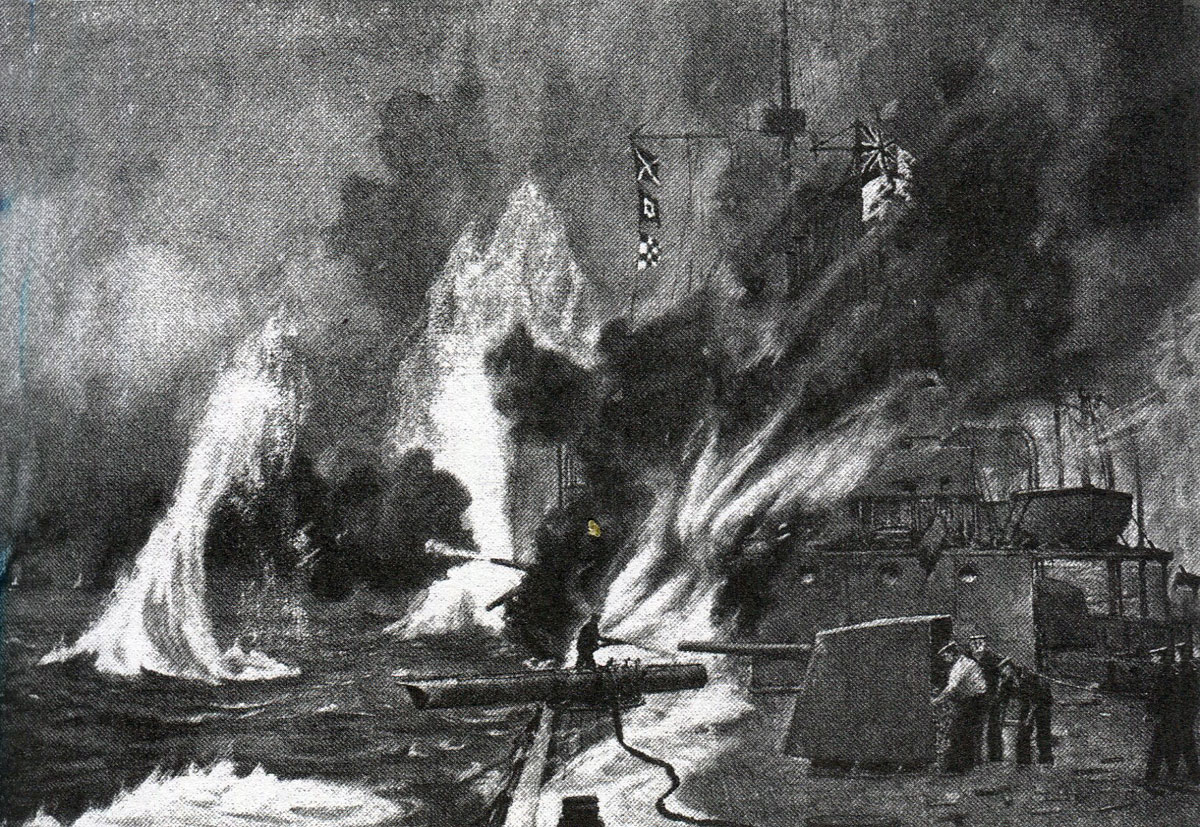

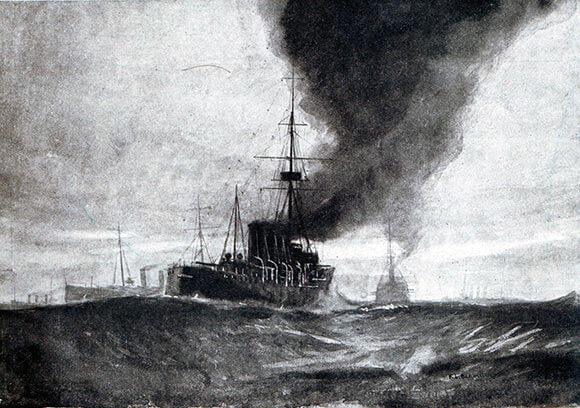

German destroyer V187 sinking during the Battle of Heligoland Bight on 28th August 1914 in the First World War

The previous battle in the First World War is the Battle of Étreux

The next battle in the First World War is the Battle of Néry

Battle: Heligoland Bight

Date of the Battle of Heligoland Bight: 28th August 1914

Place of the Battle of Heligoland Bight: In the North Sea, to the west of the Island of Heligoland, which guards the entrances to the main German naval bases.

War: The First World War, also known as ‘The Great War’.

British post card commemorating Battle of Heligoland Bight on 28th August 1914 in the First World War

Contestants at the Battle of Heligoland Bight: The British Royal Navy against the Imperial German Navy.

Ships involved in the Battle of Heligoland Bight:

Royal Navy ships

Note: In the Royal Navy, the class of ship originally termed ‘torpedo boat destroyer’, by the Great War, was abbreviated to ‘destroyer’. The German navy did not have an equivalent term. The smaller vessels were referred to as ‘torpedo boats’, whether they were what the Royal Navy would have classed as torpedo boats or destroyers. Smaller vessels in the Imperial German Navy were given an initial and a number and not a name, as with Royal Navy submarines.

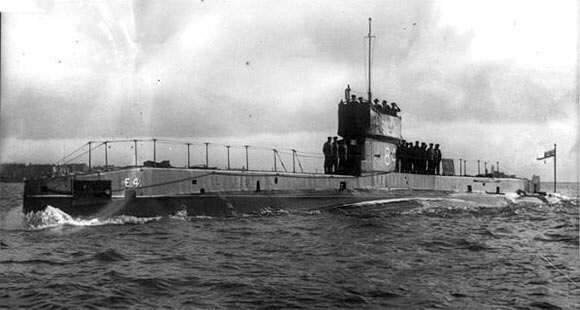

8th ‘Oversea’ Submarine Flotilla, comprising the destroyers, HMS Lurcher (Commodore Keyes) and Firedrake (both 2 X 4 inch guns), and submarines: D2, D3, E4, E5, E6, E7, E8 and E9.

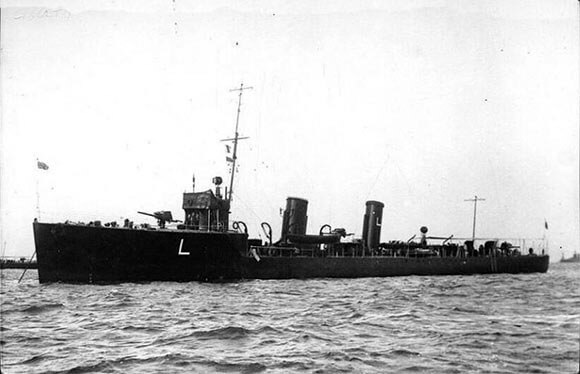

British destroyer HMS Firedrake, one of the two destroyers that acted as ‘flotilla leaders’ for the submarines of 8th ‘Oversea’ Submarine Flotilla, and took part in the Battle of Heligoland Bight on 28th August 1914 in the First World War

1st Flotilla, comprising HMS Fearless (8 X 4 inch guns) (Captain Blunt), light cruiser, and destroyers: Division 1; Acheron, Attack, Hind and Archer (all 2 X 4 inch guns): Division 2; Ariel (2 X 4 inch guns), Lucifer and Llewellyn (3 X 4 inch guns): Division 3; Ferret, Forester, Druid and Defender (all 2 X 4 inch guns): Division 4; Badger, Beaver, Jackal and Sandfly (all 2 X 4 inch guns): Division 5; Goshawk, Lizard, Lapwing and Phoenix (all 2 X 4 inch guns).

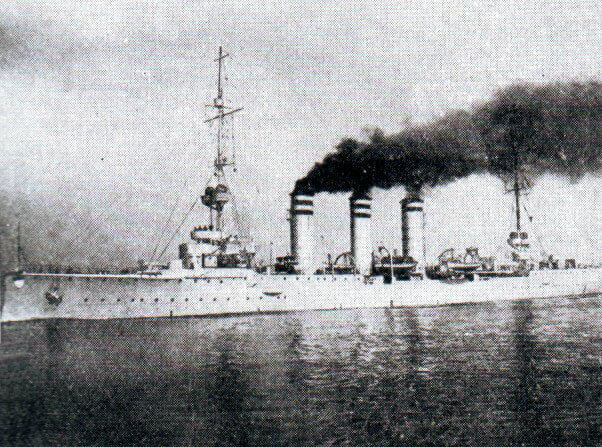

British light cruiser HMS Arethusa, Commodore Tyrwhitt’s flagship in the Battle of Heligoland Bight on 28th August 1914 in the First World War

3rd Flotilla, comprising HMS Arethusa, light cruiser (3 X 6 inch and 4 X 4 inch guns) (Commodore Tyrwhitt), and destroyers: Division 1; Lookout, Leonidas, Legion and Lennox (all 3 X 4 inch guns): Division 2; Lark, Lance, Linnet and Landrail (all 3 X 4 inch guns): Division 3; Laforey, Lawford, Louise and Lydiard (all 3 X 4 inch guns): Division 4; Laurel, Liberty, Lysander and Laertes (all 3 X 4 inch guns).

HM Destroyer Lark, one of the ships of the British 3rd Flotilla in the Battle of Heligoland Bight on 28th August 1914 in the First World War

Light Cruiser Squadron, comprising Division 1; HMS Southampton, (8 X 6 inch guns) (Commodore Goodenough) and Birmingham (9 X 6 inch guns): Division 2; Falmouth (8 X 6 inch guns) and Liverpool (2 X 6 inch and 10 X 4 inch guns): Division 3; Nottingham and Lowestoft (both 9 X 6 inch guns).

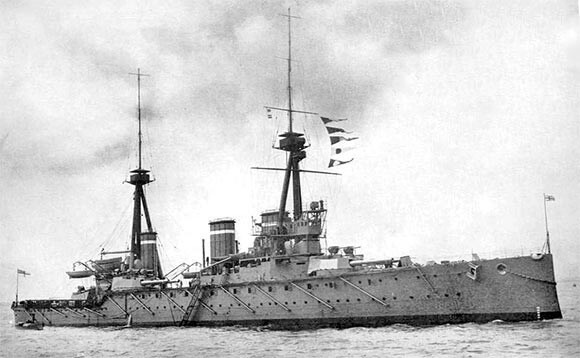

Armoured Cruisers: HMS Euryalus (2 X 9.2 and 12 X 6 inch guns) (Admiral Christian) and Amethyst, light cruiser, (2 X 6 inch and 8 X 4 inch guns): HMS Bacchante (Rear-Admiral Campbell), Cressy, Hogue and Aboukir (all 2 X 9.2 inch and 12 X 6 inch guns).

HMS Aboukir, one of the British Armoured Cruisers that took part in the Heligoland Bight operation on 28th August 1914. Aboukir, Cressy and Hogue were all sunk by the German submarine U9 on 22nd September 1914: Battle of Heligoland Bight on 28th August 1914 in the First World War

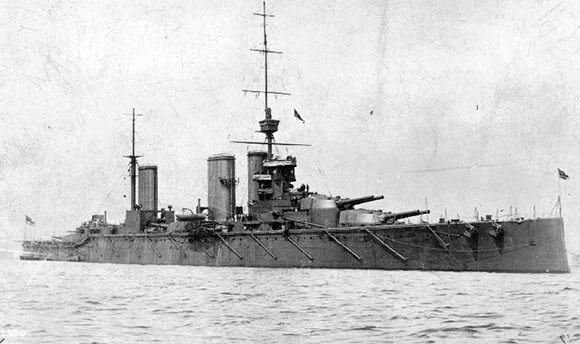

Battle Cruisers: HMS Invincible and New Zealand (both 8 X 12 inch and 12 X 4 inch guns) from the Humber (Hull) and HMS Lion (Admiral Beatty), Queen Mary and Princess Royal (all 8 X13.5 inch guns).

Map of the Battle of Heligoland Bight on 28th August 1914 in the First World War: map by John Fawkes

German ships:

Outer Patrol Line

I Torpedo Boat Flotilla

V187 (Commander Wallis), V188, V189, V190, V191, G197, G196, G193 and G194.

Inner Patrol Line

III Minesweeping Division

D8 (Lieutenant-Commander Wolfram), T25, T29, T31, T33, T34, T35, T36, T37, T49, T71 and S73.

Reinforcement

V Torpedo Boat Flotilla

G12 (Commander von dem Knesebeck), V1, V2, V3, V6, S13, G7, G9, G10 and G11.

(V187 and the other destroyers probably all 2 X 8cm guns),

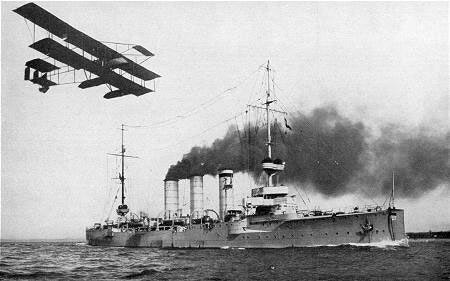

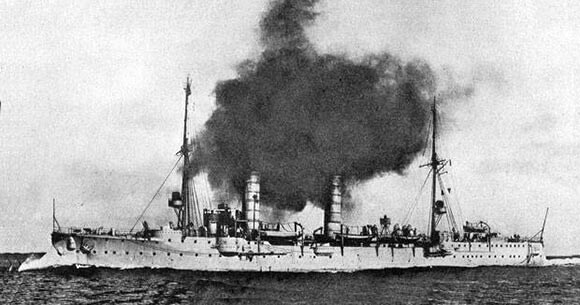

Light Cruisers: SMS Stettin (10 X 10.5 cm guns), Frauenlob (10 x 10.5 cm guns), Stralsund (12 X 10.5 cm guns), Mainz (12 X 10.5 cm guns), Cöln and Ariadne (10 X 10.5 cm guns). (10.5cm = 4.1 inches).

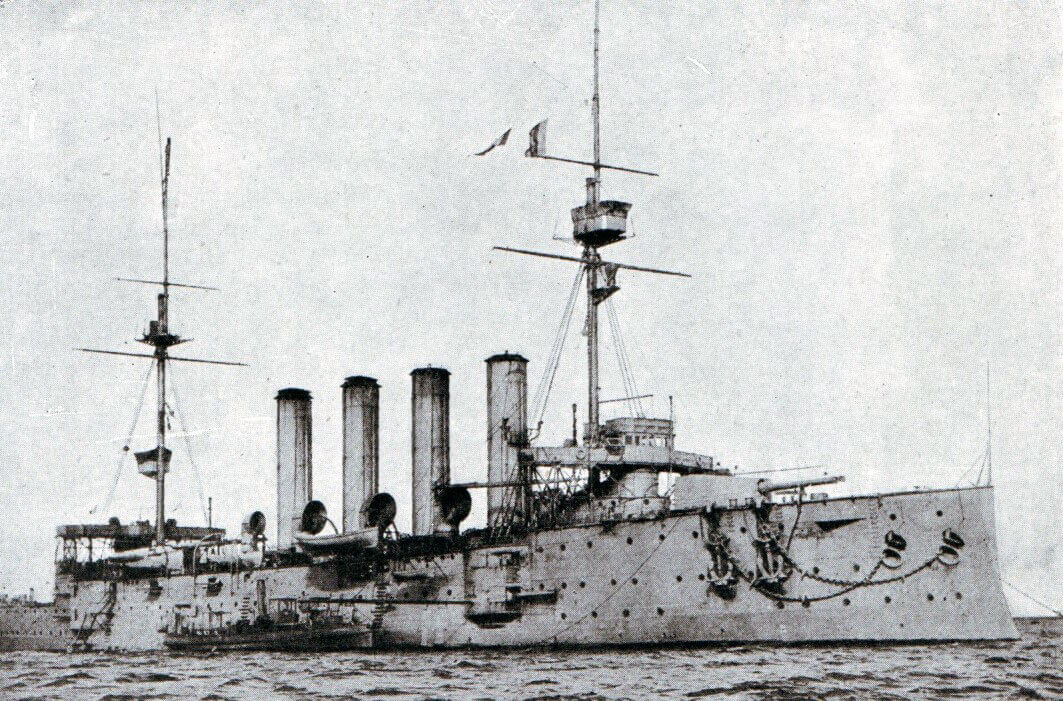

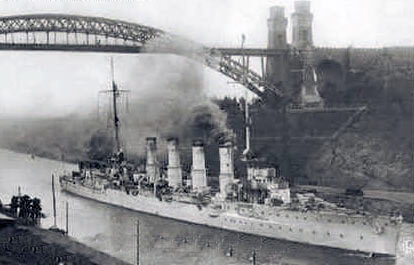

German light cruiser SMS Cöln, flagship of Admiral Maass in the Battle of Heligoland Bight on 28th August 1914 in the First World War, sunk by Admiral Beatty’s battle cruisers

All ships were equipped with ancillary armaments, including anti-aircraft guns and torpedo tubes. With engines powered by coal, or in the case of the more modern ships oil, speeds of around 25 knots were achievable by the battle cruisers and newer light cruisers and destroyers, with the older ships significantly slower depending on their condition. Communication was by radio, known then as wireless. Guns were capable of firing up to several miles, but gun control was by sight.

SMS Mainz, the German light cruiser sunk during the Battle of Heligoland Bight on 28th August 1914 in the First World War

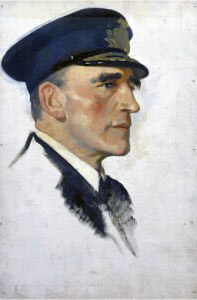

Commodore Reginald Tyrwhitt RN, commander of 1st and 3rd Destroyer Flotillas in the Battle of Heligoland Bight on 28th August 1914 in the First World War

Admiral Maass, commander of the German light cruiser squadron in the Battle of Heligoland Bight on 28th August 1914 in the First World War. Maas went down with SMS Cöln, sunk by Admiral Beatty’s battle cruisers

Commanders at the Battle of Heligoland Bight: There was no clear command structure for the British ships. Commodore Tyrwhitt commanded the force of destroyers that conducted the sweep. Commodore Keyes commanded the decoy submarines from his destroyer, HMS Lurcher. Rear Admirals Christian and Campbell commanded the supporting cruisers, which took no active part. Rear Admiral Beatty commanded the battle cruisers, with Commodore Goodenough commanding the light cruisers, from the Grand Fleet.

The German Guard Flotilla was commanded from V187 by Commander Wallis.

Rear Admiral Leberecht Maass commanded the supporting light cruisers from SMS Cöln.

Winner: While several British ships were damaged by gunfire, none were sunk; three German ships were sunk; a British victory.

Background to the Battle of Heligoland Bight:

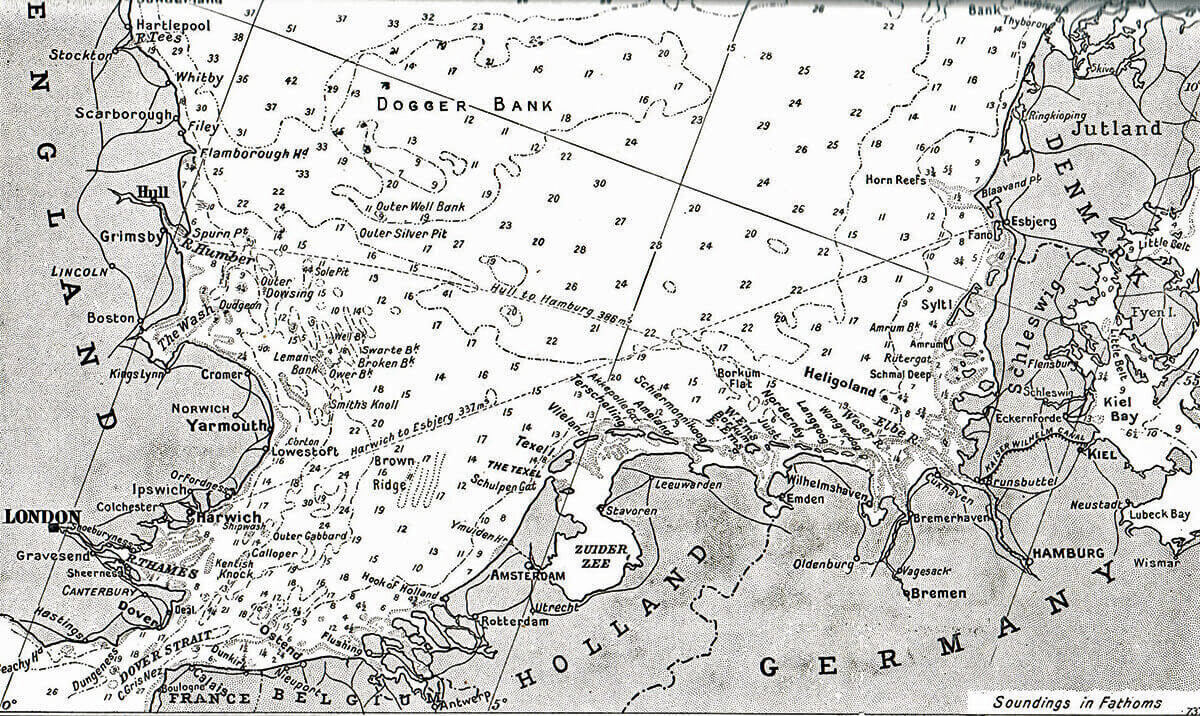

In the years preceding the First World War, as it became clear that the likely British adversary would be Germany, not, as in previous wars, France or Spain, the Royal Navy changed its home focus from facing south-west and west to facing south-east. The next naval war would primarily be fought against Germany in the North Sea.

Map of the continental North Sea coast: Battle of Heligoland Bight on 28th August 1914 in the First World War

The Royal Navy established presences in several east coast ports: Harwich, Hull, Rosyth, and built a new fleet base at Scapa Flow in the Orkney Islands. A fleet refuge for the Grand Fleet was constructed at Gairloch on the west coast of Scotland.

The German Imperial High Seas Fleet based itself in the group of ports situated on the German North Sea coast, to the south west of Denmark, in a number of estuaries; the main ports being Emden, Wilhelmshaven, Bremerhaven and Cuxhaven. Access to the Baltic Sea from these ports was established by building the Kiel Canal.

Fortifications on the German island of Heligoland in 1914: Battle of Heligoland Bight on 28th August 1914 in the First World War

Various islands provided protection for the network of German naval bases, the most important being the heavily fortified Heligoland. The recessed area of German coastline, in which several of the bases lay, is known as the ‘Heligoland Bight’. The Island of Heligoland lies mid-way across the opening to the Bight, fifty miles out to sea.

The German North Sea coast is relatively short, around 150 miles in length, along the west-east stretch, where these harbours lie, and then another 150 miles up the south-north stretch to the Danish border. Wilhelmshaven is on the same latitude as Manchester. British naval forces approaching from Harwich had to sail for around 250 miles north-north-east, to reach the German coast. Ships from Scapa Flow, base to the British Grand Fleet, and Scotland faced a voyage of around 500 miles, travelling south-east, to reach the German coast.

German destroyer at sea: Battle of Heligoland Bight on 28th August 1914 in the First World War: picture by JG Siehl Freystett

With Britain’s declaration of war on Germany at midnight on 4th/5th August 1914, and the despatch of the four divisions of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) to France between 12th and 17th August, the Royal Navy was required to mount a substantial operation, to shield the ships conveying the troops across the English Channel from German attack.

At the end of the month, it became necessary to extract the Royal Marine brigade, sent to Ostend, to evade the advancing German army. Again substantial Royal Navy cover was required for the operation.

The plan for the Heligoland Bight attack was already under consideration, with the additional reasons for the attack being that a diversion would be useful to dissuade the German Fleet from intervening in the Ostend operation, and then the operation to cover the Channel crossing of the 4th Division of the BEF (joining the 1st, 2nd, 3rd, 5th and Cavalry Divisions), followed by additional army reinforcements.

From the outset of the war, a routine of patrolling the area outside the German fleet bases was established by the British Royal Navy’s 8th ‘Oversea’ Submarine Flotilla, commanded by Commodore Keyes (HMS Lurcher), and operating from Harwich. The German Imperial Navy responded with submarine and destroyer patrols.

British submarine HMS E4, one of the vessels from 8th ‘Oversea’ Submarine Flotilla, based in Harwich, that routinely patrolled in the Heligoland Bight and acted as ‘bait’ in the Heligoland Bight operation on 28th August 1914. E4 was commanded by Lieutenant Commander Leir (see Anecdotes). She rescued the crew of HMS Dolphin’s whaler: Battle of Heligoland Bight on 28th August 1914 in the First World War

Commodore Roger Keyes RN as Rear Admiral RN in 1918. Keyes commanded the 8th ‘Oversea’ Submarine Flotilla, based at Harwich and devised the plan for the Heligoland Bight operation. Keyes was present during the Battle of Heligoland Bight on 28th August 1914 in the First World War on HMS Lurcher

The British submarines established that the German navy mounted a patrol by destroyers, moving out from Heligoland each evening to the west and north-west, and returning at dawn. These destroyers were led out and met by light cruisers. A daytime patrol covered the same area, with much the same pattern. There was further routine German ship movement around dawn.

Commodore Keyes devised a plan to attack the German night patrol as it returned in the morning, using significantly larger forces to overwhelm the German ships.

Keyes’ plan was accepted by the British Admiralty, except that it was decided to carry out the operation against the German day patrol of destroyers and light cruisers. These German ships were to be lured out to sea by a small number of British submarines, and then attacked by a large formation of British destroyers and light cruisers, supported by battle cruisers, the whole force coming from the east coast English bases.

British submarines were to take position off the German coast. More submarines were to show themselves and lure the German destroyer patrols out to sea. The British 1st and 3rd Flotillas (fifteen and sixteen destroyers), each led by a light cruiser and based in Harwich, would carry out the attacks on these German vessels. The submarines would attack any German ship that left harbour during the operation and returned to harbour at the end.

The two battle cruisers from the Humber, HMS Invincible and New Zealand, would provide immediate support to the 1st and 3rd Flotillas.

British battle cruiser HMS Invincible, one of the two battle cruisers initially allocated to support the light cruisers, destroyers and submarines conducting the sweep in the Battle of Heligoland Bight on 28th August 1914 in the First World War

Two supporting cruiser squadrons (Rear Admirals Christian and Campbell) would lie off Terschelling on the Dutch coast, and intervene if needed.

On 25th August 1914 the Ostend evacuation was ordered and it was decided to carry out the attack on the German naval patrols in the Heligoland Bight on 28th August.

British battle cruisers HMS Lion, Princess Royal and New Zealand: Battle of Heligoland Bight on 28th August 1914 in the First World War: picture by AB Cull

On 27th August when the British naval units were at sea and moving into position for the attack, the Commander-in-Chief of the Grand Fleet at Rosyth decided to send Admiral Beatty with his three battle cruisers, HMS Lion, Queen Mary and Princess Royal, and Commodore Goodenough with his six light cruisers, HMS Southampton, Birmingham, Falmouth, Liverpool, Nottingham and Lowestoft, to support the British attack.

Rear Admiral David Beatty RN. Beatty’s battle cruiser squadron was despatched by the Commander-in-Chief of the Grand Fleet, to provide support for the Battle of Heligoland Bight on 28th August 1914 in the First World War. Beatty’s ships were crucial in winning the battle, sinking the German light cruisers Cöln and Ariadne

The radio messages giving this late decision reached Admiral Christian, but did not reach the commodores commanding the destroyers and submarines, with the result that the Grand Fleet ships were nearly attacked by the British force when they arrived at the rendezvous. The submarines could not be contacted and warned of the additional British ships in the area at any stage in the operation. This led to considerable difficulty and constrained the use of the Grand Fleet ships.

A British destroyer at sea photographed from an RNAS aircraft: Battle of Heligoland Bight on 28th August 1914 in the First World War

Account:

By 4am on 28th August 1914 the British submarines were in position: E6, E7 and E8 on a north-south line 30 miles west of Heligoland Island; D2 and D3 on a north-south line south-west of Heligoland and E4, E5 and E9 around the island. All were on the surface to act as ‘bait’, to lure the German ships from harbour.

The plan was that the two British destroyer flotillas, after the approach to the area north of Heligoland, would turn south and steam to a point twelve miles to the west of Heligoland, with the battle cruisers to their starboard, reaching this point at 8am on 28th August 1914 and then turn west and begin the sweep to catch the German destroyers lured out to sea by the British submarine line.

The Germans were warned of the presence of a significant British force off their coast by the increased radio traffic late on 27th and early on 28th August. The German navy implemented its own plan, which was the converse of the British; to deploy destroyers to lure any approaching British ships nearer the German shore and attack them with light cruisers. This plan clearly did not anticipate the presence of British ships of the force of battle cruisers, as the Germans were unable to put their own battle cruisers to sea until after the battle was over and the British had retired.

The weather was calm and misty, causing problems with observation and identification.

Commodore Tyrwhitt led the British approach in HMS Arethusa, a modern light cruiser, with the 3rd Flotilla (sixteen destroyers), followed, a mile astern, by the destroyers of 1st Flotilla (fifteen ships), headed by the light cruiser HMS Fearless.

British light cruiser HMS Fearless. Fearless led the 1st Destroyer Flotilla in the Battle of Heligoland Bight on 28th August 1914 in the First World War

Eight miles astern of the destroyers were Goodenough’s six light cruisers.

The five battle cruisers, led by Beatty, steamed on the starboard flank of the destroyers.

At 7am a German destroyer appeared 3 ½ miles to the south east of the British. It turned and headed into the Heligoland Bight, pursued by the four destroyers of Tyrwhitt’s 4th Division, where more German destroyers appeared. The two groups fired on each other at extreme range.

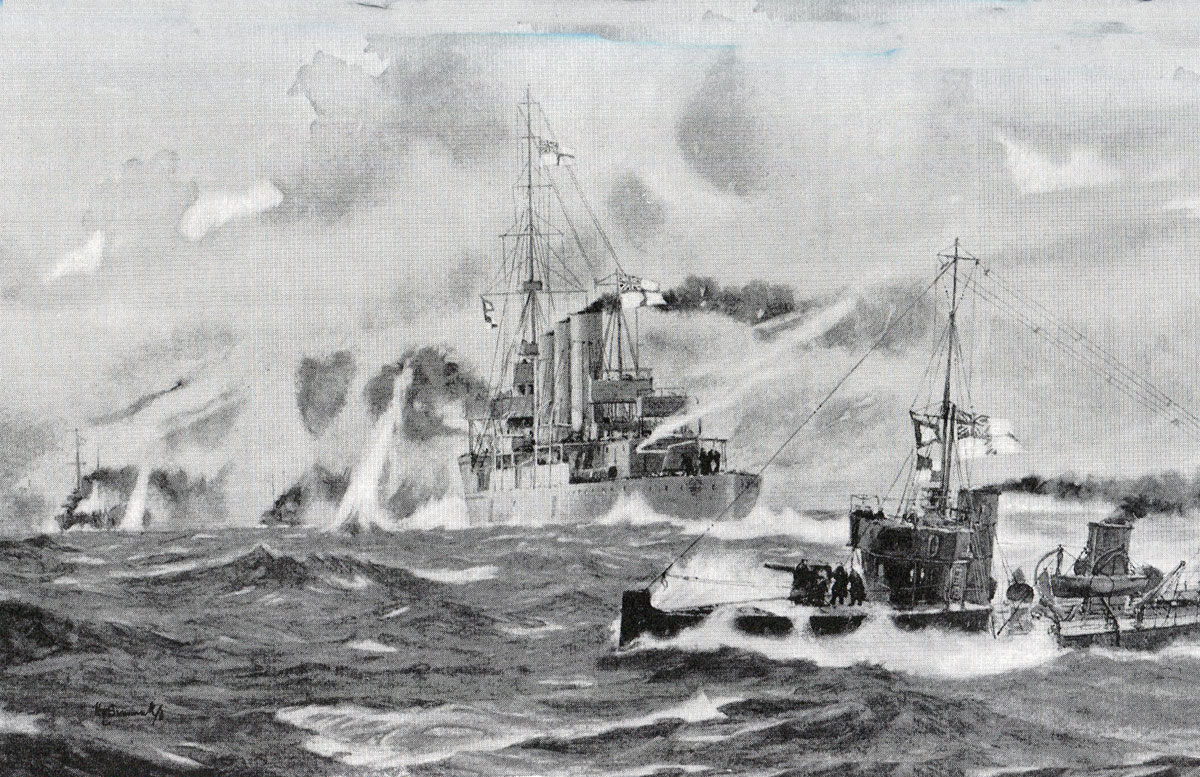

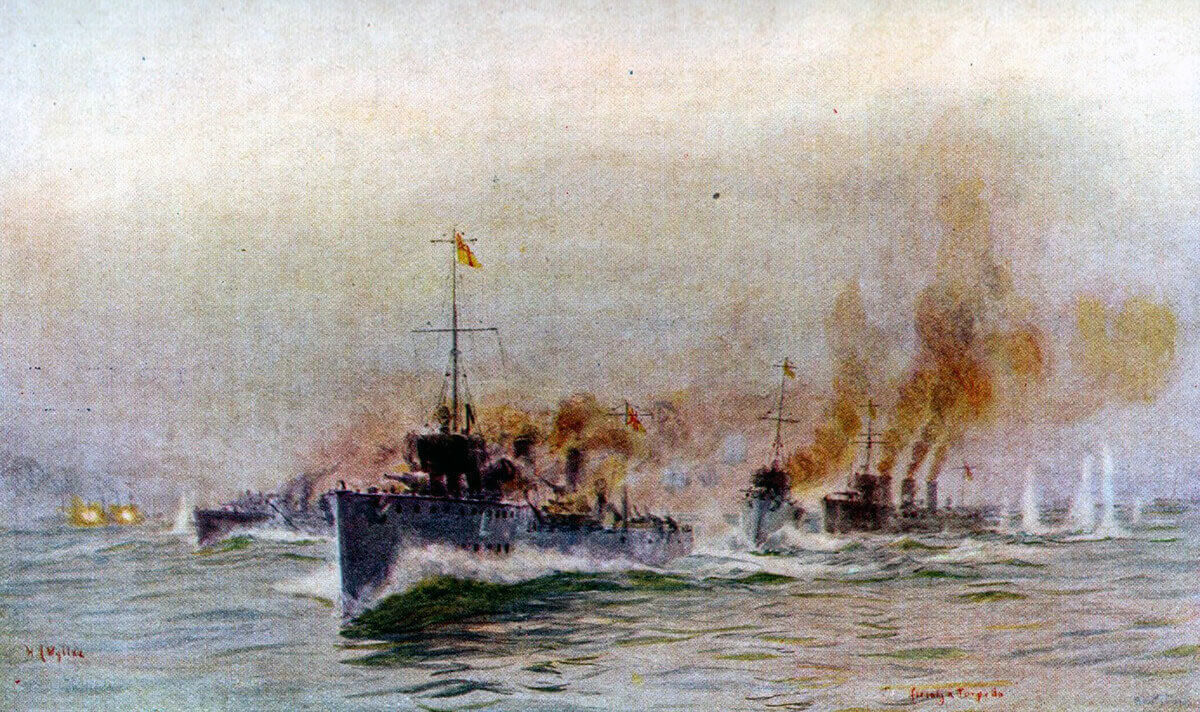

HMS Arethusa and the Harwich Destroyers engage German Torpedo Boats in the Battle of Heligoland Bight on 28th August 1914 in the First World War

All the ships involved, British and German, were at this point to the north-west of the Island of Heligoland.

More German destroyers appeared and Tyrwhitt at 7.40am turned two points to port and pursued both groups with his two British destroyer flotillas, firing at extreme range, although observation was hindered by the mist.

Operations throughout the day were hampered by the patches of mist, ships appearing and disappearing in the changing conditions.

This pursuit continued for around an hour, when at 8am, two German light cruisers, SMS Stettin and Frauenlob, came up on Tyrwhitt’s port side, converging with the British ships.

German light cruiser SMS Frauenlob, one of the German ships that attacked the British destroyers in the Battle of Heligoland Bight on 28th August 1914 in the First World War

Tyrwhitt’s ship Arethusa engaged the German light cruisers supported by the destroyers, but quickly received damage from the gunfire of the two German ships.

At around 8.15am Blunt in the British light cruiser HMS Fearless, came up with the British 1st Destroyer Flotilla and engaged Stettin, which turned away towards Heligoland pursued by Blunt’s ships.

German light cruiser SMS Stettin, one of the German ships that attacked the British destroyers in the Battle of Heligoland Bight on 28th August 1914 in the First World War

Tyrwhitt continued to engage Frauenlob, which steamed away to the south. Tyrwhitt’s ship Arethusa suffered significant damage with most of her guns out of action.

Some of the British destroyers engaged a tramp steamer attempting to lay mines in front of the Arethusa and others shot up a German torpedo boat.

At around 8.10am Tyrwhitt signalled the 1st Flotilla to begin the sweep to the West. Blunt took Fearless and his destroyers off on the sweep, while Tyrwhitt continued to engage Frauenlob.

HMS Arethusa engages SMS Stettin and Frauenlob in the Battle of Heligoland Bight on 28th August 1914 in the First World War

Frauenlob received a hit under the fore bridge, and made off towards Heligoland, heavily damaged. Tyrwhitt turned to join the westward sweep at around 8.30am.

Both British destroyer flotillas were now steaming west, away from the Island of Heligoland. Blunt’s 1st Flotilla, led by the light cruiser Fearless, was fifteen minutes into the sweep, further north and to the west of Tyrwhitt’s 3rd Flotilla.

Soon after beginning the sweep the 1st Flotilla encountered the German destroyer V187 . Blunt’s ships fired on V187, but then fearing the ship might be Commodore Keyes in HMS Lurcher Blunt permitted V187 to steam away to the south-west.

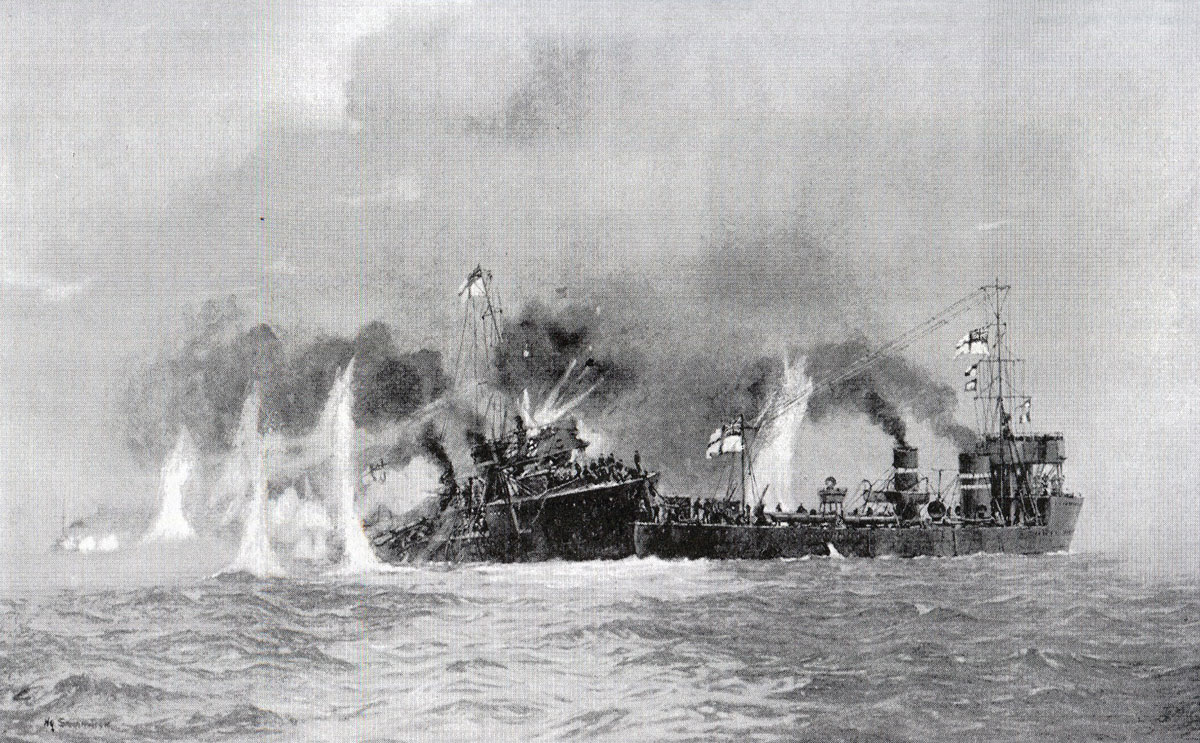

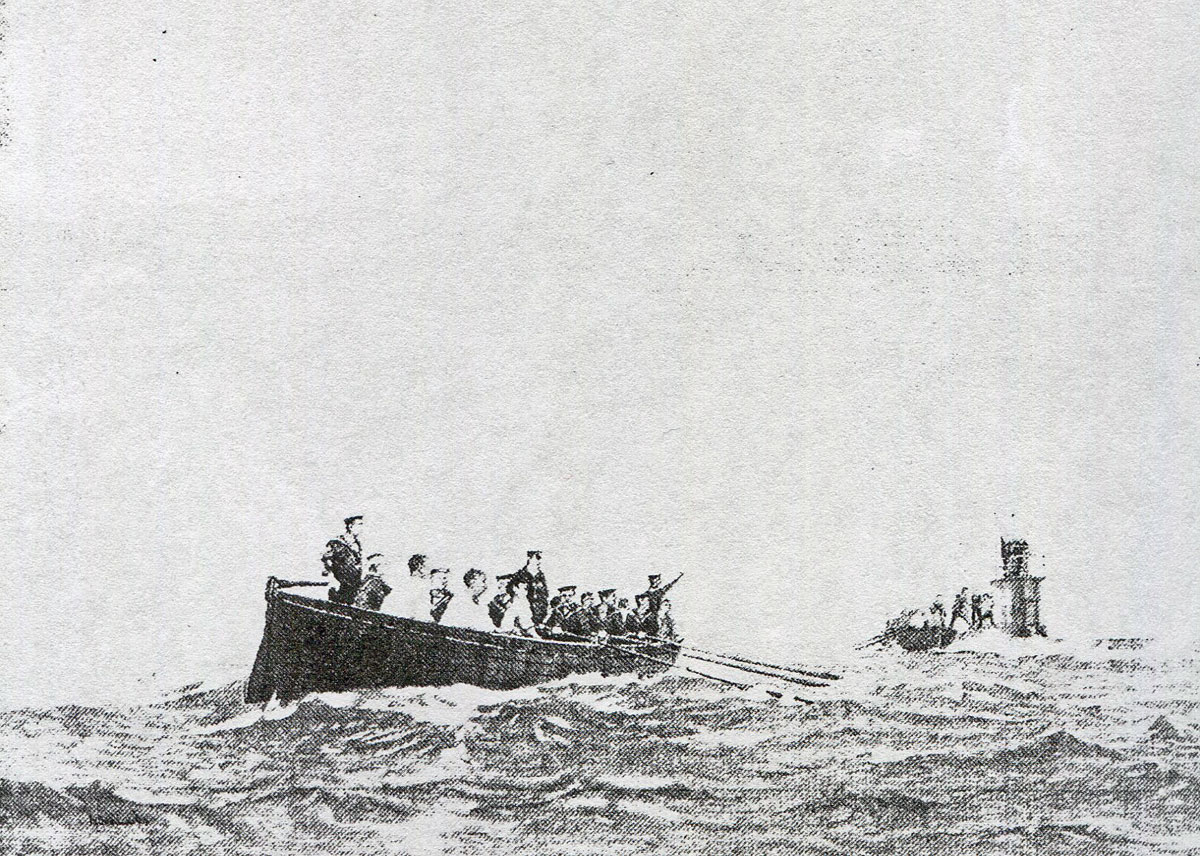

V187 then appears to have seen the two British light cruisers, Nottingham and Lowestoft, and turned back to the north, where she encountered the eight British destroyers of 1st Flotilla’s 3rd and 5th Divisions. The British destroyers opened fire on V187 and after putting up a strenuous resistance V187 was sunk.

German Torpedo Boat V187, sunk by Blunt’s destroyers during the westward sweep in the Battle of Heligoland Bight on 28th August 1914 in the First World War

At this point Admiral Beatty with the battle cruisers was in a position some fifty miles to the west-north-west of the Island of Heligoland. Commodore Goodenough with his light cruisers was in position west-south-west of Heligoland. Goodenough had detached HMS Nottingham and Lowestoft to assist Tyrwhitt in the fight with Stettin and Frauenlob. The rest of his squadron saw and pursued a number of German destroyers, all of which escaped in the mist.

British light cruiser HMS Lowestoft, part of Commodore Goodenough’s light cruiser squadron in the Battle of Heligoland Bight on 28th August 1914 in the First World War

During this period, 8 to 9am, an incident occurred that might have been disastrous for the British force. Commodore Keyes in the destroyer HMS Lurcher (Keyes commanded the submarine flotilla) was checking the area over which the battle cruisers HMS Invincible and New Zealand were due to pass for German submarines. Keyes was unaware that battle cruisers and light cruisers from the Grand Fleet had joined the British force. Keyes saw 2 ships in the mist, which were probably Nottingham and Lowestoft.

Keyes followed them and signalled the presence of German ships to the two battle cruisers.

Goodenough also heard Keyes’ signal and steamed up to assist Keyes. Keyes saw Goodenough’s ships approaching in the mist and being unaware of their presence in the force reported that there were four German cruisers and that he was pursued and attempting to lure them towards Invincible and New Zealand.

British battle cruiser HMS New Zealand during the Battle of Heligoland Bight on 28th August 1914 in the First World War

Goodenough turned away to the West, where he encountered a British submarine in the screen, which he attempted unsuccessfully to sink.

By about 9.05am all the British ships, whether aware of each other’s presence or not, had turned west and joined the sweep, except for Nottingham and Lowestoft which failed to receive the radio message.

There was then another hitch at around 9.45am, when Tyrwhitt received a further message that HMS Lurcher was being chased. He stopped his destroyer’s progression west and headed back towards the east to look for Lurcher with 1st and 3rd Flotillas.

6 inch gun in action on HMS Arethusa in the Battle of Heligoland Bight on 28th August 1914 in the First World War

SMS Stettin appeared from the east, was pursued by Tyrwhitt and disappeared into the mist.

Approaching Heligoland, Tyrwhitt was rejoined by 3rd and 5th Divisions of his flotilla, with reports that they had sunk V187 at around 9am. During this action a German light cruiser, probably the Stettin, had appeared and intervened. The effect of this intervention, although too late to save V187, already sinking, was to force the British destroyers hastily to leave the area, abandoning many of the German survivors still in the sea. In addition HMS Defender, under heavy fire from Stettin, was forced to leave her whaler which was rescuing German seamen. The British crews of two small boats were later recovered by HMS E4, which had been watching the fight. E4 made an unsuccessful attempt to torpedo the Stettin.

E4 surfaced at 10.10am took off the British seaman and selected three prisoners, treated the German wounded, supplied the remaining German seamen and gave them the correct course for Heligoland, before submerging.

British destroyer HMS Lurcher, flagship of Commodore Keyes RN in the Battle of Heligoland Bight on 28th August 1914 in the First World War

Tyrwhitt despatched his 1st flotilla, now complete with the 3rd and 5th Divisions, to resume the sweep to the west, retaining the 3rd Flotilla while he carried out emergency repairs to his own ship, HMS Arethusa.

Goodenough and Keyes had by this time sorted out the muddle over the presence of Goodenough’s light cruiser squadron and Beatty’s battle cruisers. There was however no way of informing the British submarines of the presence of the British light cruiser squadron and it was decided that Goodenough’s ships should withdraw from the area rather than risk an attack upon them by British submarines.

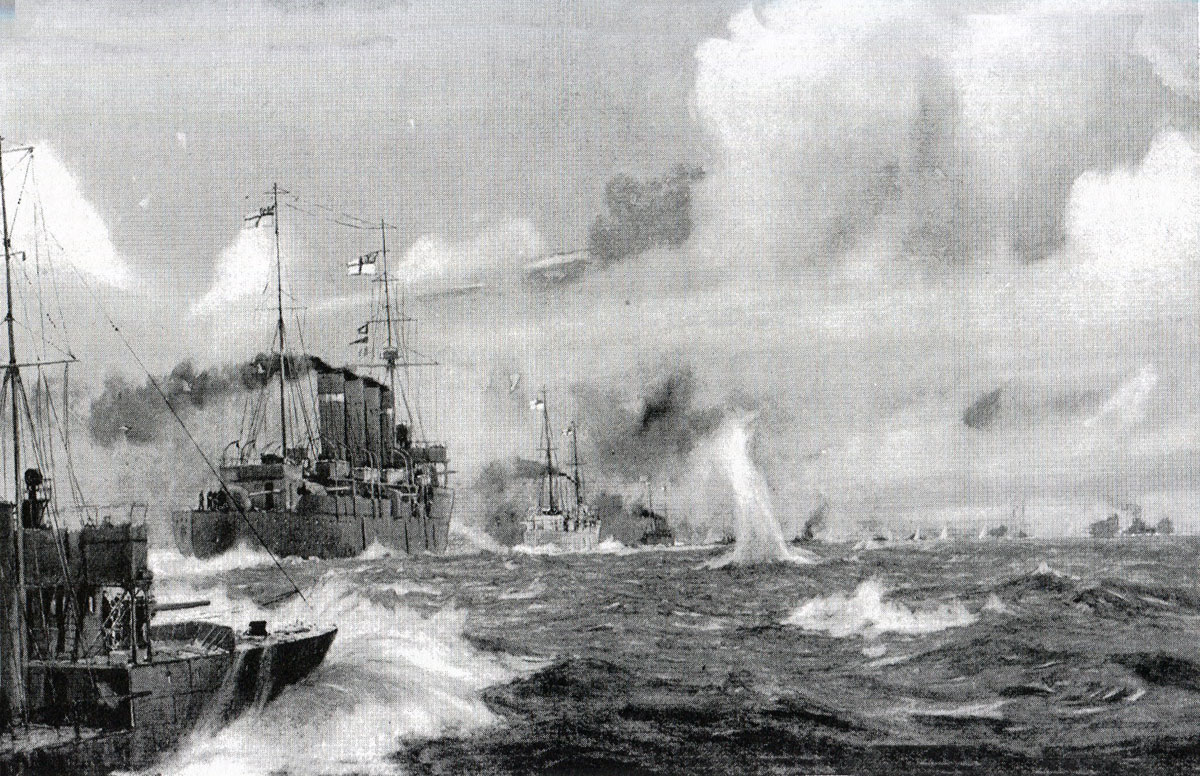

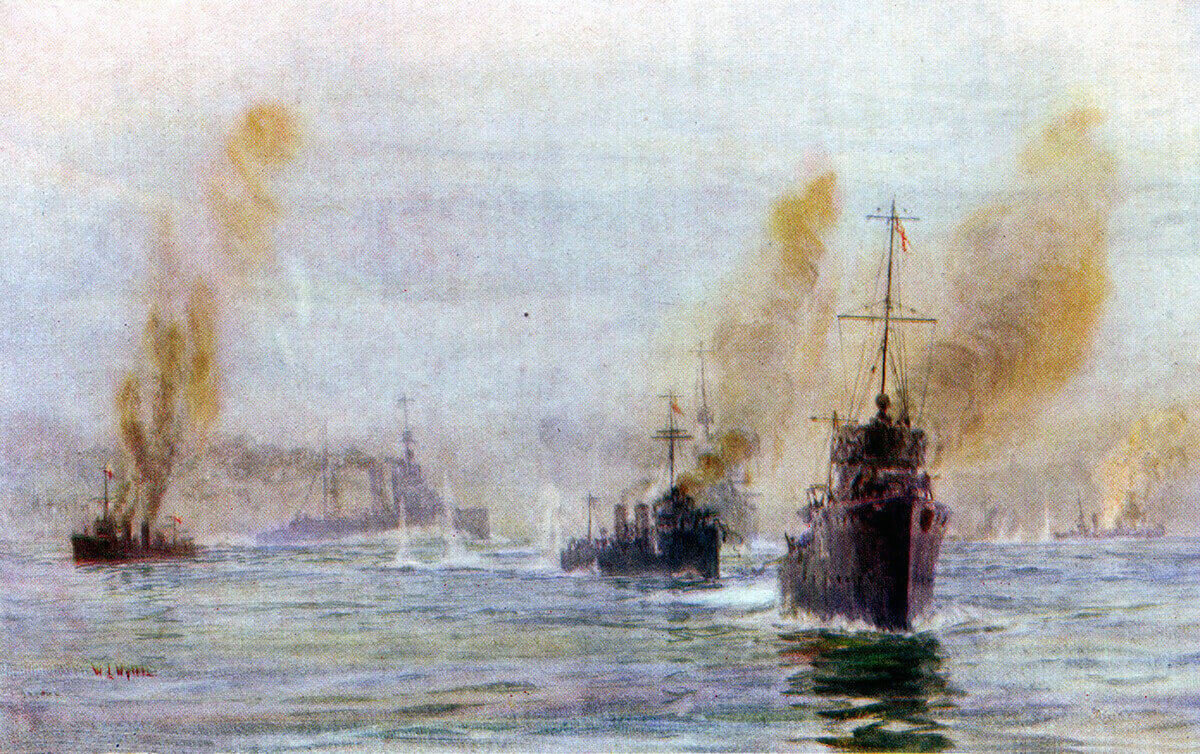

Commodore Goodenough’s Light Cruiser Squadron goes into action in the Battle of Heligoland Bight on 28th August 1914 in the First World War

At around 10.40am Commodore Tyrwhitt had completed sufficient repairs on Arethusa to bring several of her guns back into commission. Arethusa, Fearless and the destroyers of the 3rd Flotilla re-commenced the sweep to the west, away from Heligoland to which they were dangerously close.

Within ten minutes a German cruiser was spotted sailing up from the south-east towards the North. It proved to be SMS Stralsund which opened accurate and heavy fire on the damaged Arethusa, now, due to the damage received, capable of only ten knots.

German light cruiser SMS Stralsund, passing through the Kiel Canal. Stralsund was one of the German ships that attacked the British destroyers in the Battle of Heligoland Bight on 28th August 1914 in the First World War

Tyrwhitt called Blunt to his aid and Fearless and the 1st destroyer flotilla turned to assist in the attack on the Stralsund. Stralsund was hit and sheered off towards Heligoland. Tyrwhitt, fearing a trap, did not follow the German light cruiser.

While the action involving Stralsund was in progress, the 3rd Flotilla turned back towards the sound of gunfire. Tyrwhitt came up with Fearless and the sweep to the west was resumed by both flotillas.

British destroyers rescuing the crew of V187 during the Battle of Heligoland Bight on 28th August 1914 in the First World War

At this point SMS Stettin re-appeared from the east and opened fire on Fearless. The two British light cruisers turned back and the three cruisers began to fight it out, the British destroyers continuing the sweep to the west.

At 11.15am the destroyers of the 3rd Flotilla decided to support the two British cruisers and turned back towards Heligoland, heading for the sound of gunfire. As they approached Tyrwhitt signalled them to attack the Stettin with torpedoes. Tyrwhitt also radioed to Beatty for assistance.

British destroyers engaging SMS Mainz during the Battle of Heligoland Bight on 28th August 1914 in the First World War: picture by Lionel Wyllie

At 11.30am the Stettin withdrew from the fight, but was replaced by Stralsund, which re-appeared from the north and opened a heavy and accurate fire on Arethusa, damaging her further. Tyrwhitt repeated his call to Beatty for assistance.

The destroyers of the 3rd Flotilla raced to attack Stralsund with torpedoes. Although they did not achieve any hits, Stralsund turned away and again broke off action.

At 11.15am the 1st Flotilla, which was continuing to the west, saw a ship approaching from the south-west. This was the German light cruiser SMS Mainz, which had been seen by the British submarine D2 to leave Borkum in the Ems Estuary and make off at high speed to the east, heading towards Heligoland. During the course of this voyage Mainz was ordered to go to the assistance of Stralsund and turned to the north-east, meeting the British destroyers of the 1st Flotilla heading westwards.

British destroyer HMS Liberty; one of the destroyers of 4th Division of 1st Destroyer Flotilla, heavily damaged by gunfire from SMS Mainz during the Battle of Heligoland Bight on 28th August 1914 in the First World War

The divisions of the 1st Flotilla turned to the north to put themselves in line ahead for an attack on Mainz, now sailing north. Before this attack could develop, Commodore Goodenough’s four light cruisers appeared from the west, and opened fire on Mainz. Heavily outnumbered, Mainz turned to the south to make her escape.

The 3rd Flotilla had formed up on Arethusa to resume the westward sweep when the Mainz appeared, heading across their front to the south to escape from the fire of the British light cruisers of Goodenough’s squadron, which were closing in from its starboard quarter on a converging course.

British light cruiser HMS Arethusa limps into Harwich after the Battle of Heligoland Bight on 28th August 1914 in the First World War: picture by FL Blanchard

Arethusa and Fearless turned towards the south, and opened fire on the Mainz, signalling to the destroyers to engage the German ship. The British destroyers turned to attack. The position of the 4th Division put it nearest to the Mainz and the 4 destroyers of that division received a destructive fire from the Mainz: Laurel fired two torpedoes and was then hit by a salvo, Liberty was hit and her captain killed, Lysander was not hit and Laertes was hit by every shell from a salvo, bringing her to a complete stop.

British destroyer HMS Laertes, one of the destroyers of 4th Division of 3rd Destroyer Flotilla, heavily damaged by gunfire from SMS Mainz during the Battle of Heligoland Bight

Mainz avoided the torpedo attack from the destroyers, but was suffering badly from the gunfire of Arethusa and Fearless.Mainz turned towards the British destroyers, but was met with a heavy fire and a further torpedo attack, with one or possibly two hits. Mainz turned back towards the south to get away, but was now heading towards the closing British light cruisers of Goodenough’s squadron.

The fire from Arethusa, Fearless and the destroyers was proving decisive and Mainz’ engines failed, bringing her to a halt. Tyrwhitt signalled his ships to resume the sweep to the west, leaving the Mainz to Goodenough’s light cruiser squadron.

Goodenough’s ships opened fire on the German light cruiser. In a few minutes Mainz was a blazing wreck and at 12.50pm she struck her colours.

HMS Lapwing of 1st Flotilla attempting to take HMS Laertes of 3rd Flotilla in tow during the Battle of Heligoland Bight on 28th August 1914 in the First World War

After leaving Mainz, Tyrwhitt’s ships began to receive fire from the north. Arethusa caught sight of Stralsund through gaps in the mist, returning to the attack, and fired on her. Fearless moved across Arethusa’s stern to assist the destroyers of her 4th Division after the pounding they had received from Mainz. As she did so, Fearless saw a further two German light cruisers coming down from the north-east, SMS Cöln, flying the flotilla admiral’s flag, followed by Stettin. Further to the rear was the German light cruiser, SMS Ariadne.

The sinking of the German light cruiser SMS Mainz during the Battle of Heligoland Bight on 28th August 1914 in the First World War; photograph taken from the deck of a British light cruiser

Arethusa and Fearless with the destroyers of the 3rd Flotilla and the 4th Division of the 1st Flotilla were now in serious difficulty, under attack by the three German light cruisers.

Commodore Goodenough’s Light Cruiser Squadron at the Battle of Heligoland Bight on 28th August 1914 in the First World War

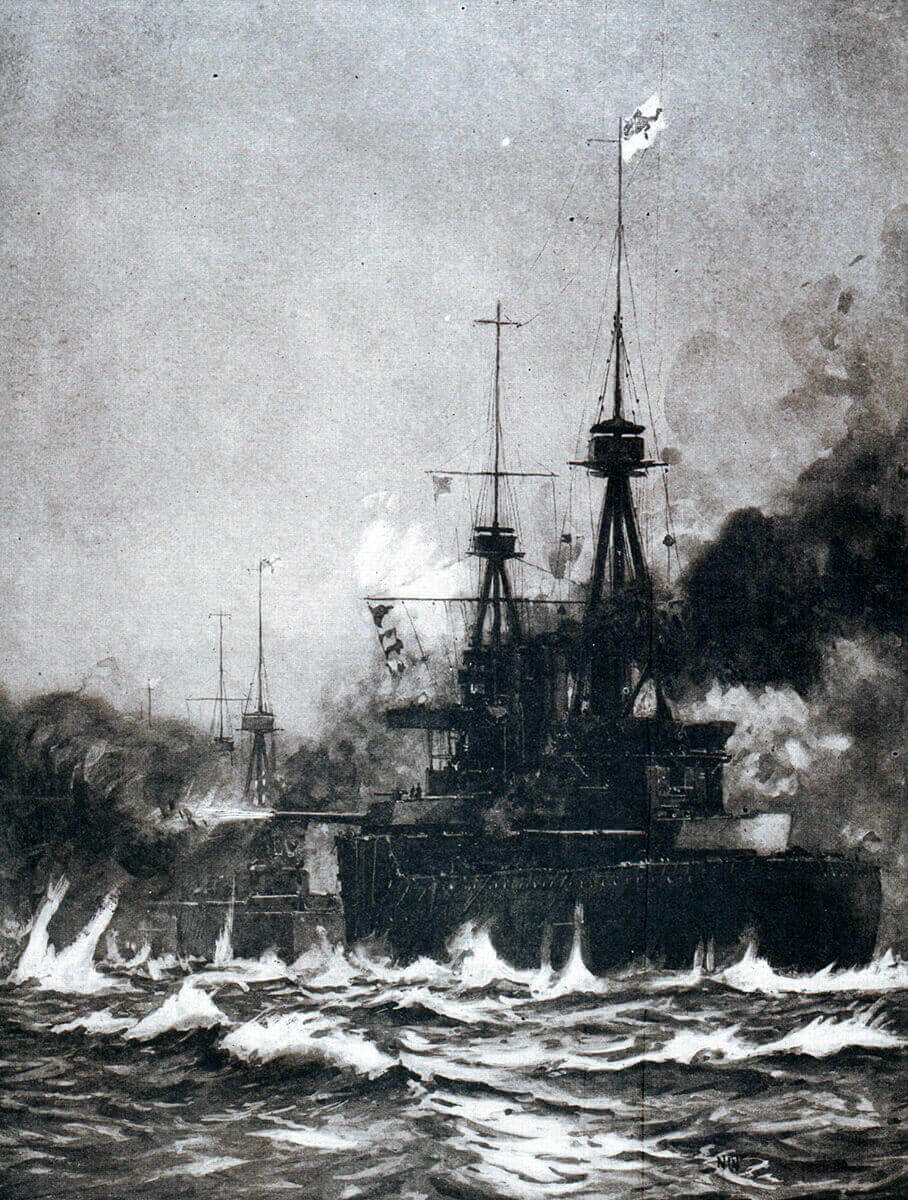

Admiral Beatty, commanding all five of the battle cruisers, had decided to follow the light cruisers of Commodore Goodenough’s squadron into the battle area, to provide further support in case it should be needed. It was a difficult decision as it took his valuable ships nearer to the German coast and into an area where there were likely to be submarines, both German and, unfortunately, British submarines that were unaware of the presence of his ships and might well attack him.

British battle cruiser HMS Lion, Rear Admiral Beatty’s flagship at the Battle of Heligoland Bight on 28th August 1914. The three ships of Beatty’s battle cruiser squadron, from the Grand Fleet based at Scapa Flow in the Orkneys, were sent to assist in the Battle of Heligoland Bight on 28th August 1914 in the First World War. Their presence proved decisive, the ships sinking the German light cruisers, SMS Cöln and Ariadne

When Beatty heard the firing further to the east, where Tyrwhitt’s ships heavily outgunned were combating the three German light cruisers. Beatty turned towards the firing with Goodenough’s ships, less Liverpool which was left to assist in recovering the survivors from Mainz.

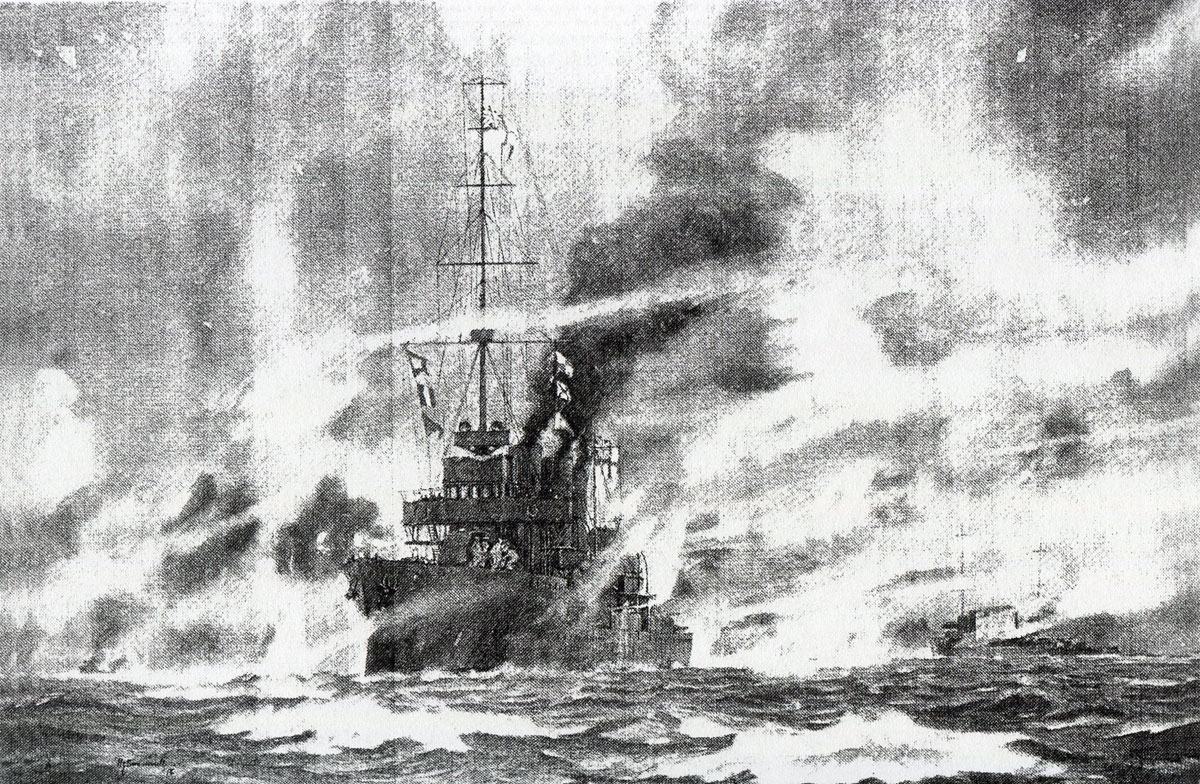

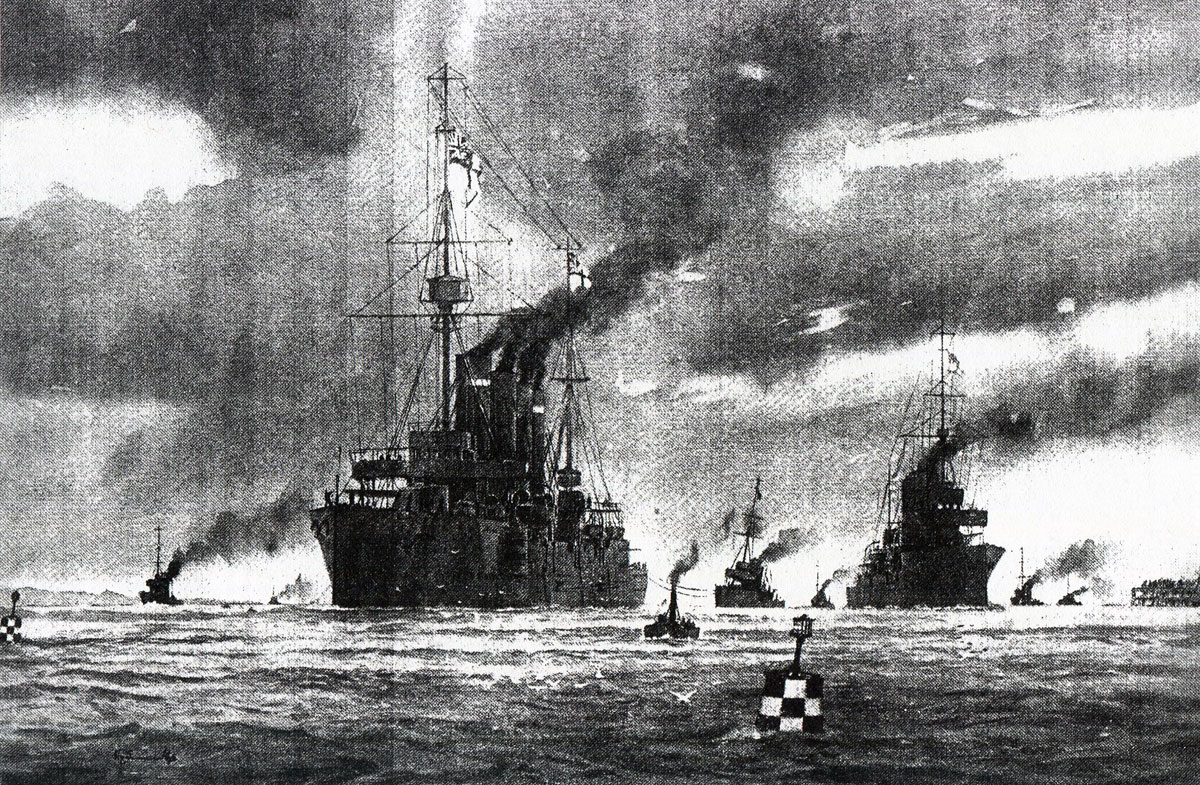

Beatty’s battle cruisers arriving in the nick of time at the Battle of Heligoland Bight on 28th August 1914 in the First World War: picture by Lionel Wyllie

As Arethusa and Fearless fought the three German light cruisers Beatty’s five battle cruisers loomed out of the mist from the west, followed by Goodenough and the rest of the 1st Flotilla.

Beattie’s battle cruisers in action at the Battle of Heligoland Bight on 28th August 1914 in the First World War

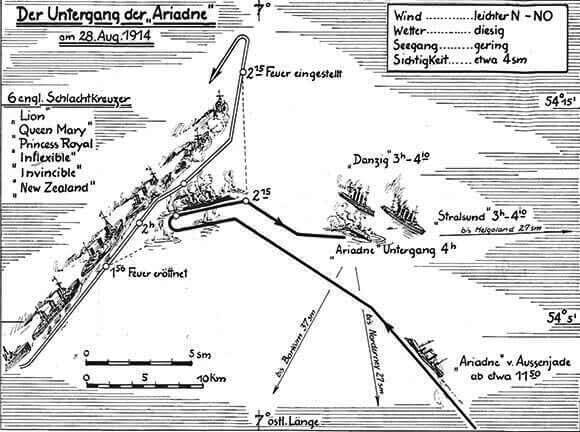

As soon as the leading British battle cruiser HMS Lion appeared, Cöln and Stettin turned and headed east. The five British battle cruisers pursued and slowly overhauled the two German ships. Course was altered and a devastating fire opened from the British heavy guns, hitting Cöln. Beatty was then notified by Arethusa of the presence of another German ship, SMS Ariadne. Beatty could not divide his force, in view of their precarious position so near to the main German naval bases. Beatty altered course with the whole force to intercept the Ariadne, leaving Cöln limping towards Heligoland.

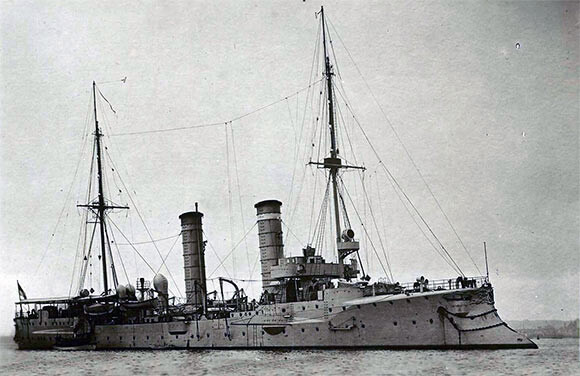

German light cruiser SMS Ariadne, sunk by Beatty’s battle cruisers during the Battle of Heligoland Bight on 28th August 1914 in the First World War

Ariadne was intercepted and quickly sunk by salvos from the heavy guns of the British battle cruisers. Beatty then returned to where Cöln had last been seen. Cöln had made little progress. At 1.25pm the mist lifted to reveal the badly damaged German light cruiser. Two salvos were sufficient to sink the Cöln.

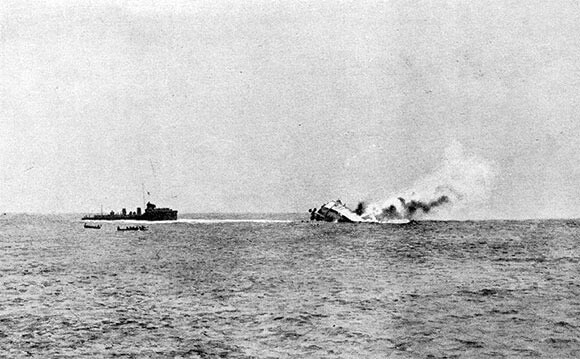

German light cruiser SMS Ariadne under attack by Beatty’s battle cruisers and about to sink during the Battle of Heligoland Bight on 28th August 1914 in the First World War

The British destroyers attempted to rescue the German survivors from the Mainz. In the end Keyes laid Lurcher alongside the German cruiser, in order to take off the wounded lying on the deck. Mainz capsized and went down very suddenly, narrowly missing the Lurcher. The German flotilla admiral, Admiral Maass, was lost with 380 crew.

German light cruiser SMS Mainz sinking during the Battle of Heligoland Bight on 28th August 1914 in the First World War. The ship on the left is HMS Lurcher taking off German survivors. The boats are from HMS Liverpool

Aftermathto the Battle of Heligoland Bight:

Once the battle was finished, the British ships withdrew from the area to their home bases. Arethusa had to be taken in tow by the cruiser Hogue.

German battle cruisers arrived in the area at some stage after the British withdrawal. The survivors of the Ariadne were rescued from the sea by the battle cruiser Von der Tann.

It is thought that the loss of three light cruisers and a destroyer as against no British ship losses, caused the Kaiser to restrict the actions of the German High Seas Fleet.

The battle raised British naval morale and put in serious doubt the German claim that their navy was the coming force, attacked successfully as they had been in their own ‘back yard’.

German plan of the final stage of the Battle of Heligoland Bight on 28th August 1914 in the First World War, showing the sinking of the German light cruiser SMS Ariadne. The plan is wrong in giving the presence of HMS Inflexible. Inflexible was in the Mediterranean Fleet

Winston Churchill wrote of the battle: “Henceforward the weight of British naval prestige lay heavy across all German sea enterprises …. the German Navy was indeed muzzled. Except for furtive movements by individual submarines and minelayers not a dog stirred from August to November.” (this was an exaggeration as there was significant German submarine activity, which led to the loss of the three British cruisers, HMS Hogue, Aboukir and Cressy, sunk by a German submarine the U9 on 22nd September 1914).

The performance of the Royal Navy’s submarines was a disappointment. Although they were involved with German destroyers no German losses were inflicted by the submarines during the action.

HMS Hogue tows HMS Arethusa into harbour after the Battle of Heligoland Bight on 28th August 1914 in the First World War

Casualties at the Battle of Heligoland Bight:

British: Arethusa: Lieutenant Westmacott and 10 men were killed. 1 officer and 16 men were wounded. The destroyer casualties were mainly in the 4th Division, shot at by Mainz. Overall there were around 35 killed and 40 wounded. Two destroyers in the 4th Division of 3rd Flotilla were badly damaged; Liberty and Laertes.

British ships moving casualties and prisoners by boat after the Battle of Heligoland Bight on 28th August 1914 in the First World War: picture by Lionel Wyllie

German: The German light cruisers SMS Mainz, Cöln and Ariadne were sunk: The whole crew of Cöln, less the one stoker picked up, were lost including the admiral; 380 men. 348 crew of Mainz were rescued and made prisoner. 32 died. Ariadne: the captain and 2 officers were lost with 70 men. The number of wounded is unknown. From V187, the German commodore, another officer and 26 men were taken prisoner. The remainder of the crew of V187 had to be left in boats to be picked up by German ships at a later time. German total casualties are thought to have been around 1,000.

Petty Officer A. Britton on HMS Laurel winning the DSM in the Battle of Heligoland Bight on 28th August 1914 in the First World War

Anecdotes and traditions from the Battle of Heligoland Bight:

Senior Stoker Olf Neumann, the sole survivor from the crew of the German light cruiser SMS Cöln, sunk by Admiral Beatty’s battle cruisers in the Battle of Heligoland Bight on 28th August 1914 in the First World War

• Some of the German survivors from Mainz were found to have been shot in the back by their own officers, presumably for attempting to leave the ship.

• It was a German complaint that the British failed to rescue the crew of SMS Cöln, leaving them in the sea. German ships searched the area and three days later found the one survivor, Senior Stoker Olf Neumann.

• The British were struck by the very determined resistance put up by V187 and by the accurate shooting from all the German ships, particularly the Mainz.

• The German tactics left a great deal to be desired. The light cruisers’ actions were ill-co-ordinated and hesitant, advancing and withdrawing, then advancing again.

• The British staffing of the action was un-impressive, in particular in the failure to ensure that all ships taking part in the operation were aware that Admiral Beatty’s battle cruisers and Commodore Goodenough’s light cruisers from the Grand Fleet had joined the force, albeit at the last moment. Commodore Keyes commented after the action “It means so much to a ship to know that, if she falls in with another, it is beyond the shadow of doubt a friend or an enemy; indeed it is the essence of good Staff work to ensure that this is possible.”

• It is clear that without these additional powerful ships (Beatty’s three battle cruisers) the force was inadequate for the task it was given. It was wholly foreseeable that German re-enforcements would intervene. It was lucky that the immediate intervention was only by four light cruisers.

• Commodore Keyes was admonished by the First Sea Lord, after the battle, for personally leading his submarines in HMS Lurcher. His role as commander of the submarine flotilla required him to remain on land. It was hard to make Keyes stick to his instructions. He was determined to lead his submarines from a ship. Keyes anticipated the war by cancelling all leave for his submarine flotilla several days before the formal mobilisation order for the Fleet and ordering his submarines to move from their peacetime stations on the South Coast to their war stations at Harwich on the East Coast. After a false start, which saw the submarines ordered to Grimsby, Keyes led his command to Harwich and prepared for war.

• HMS Arethusa and Fearless were well handled. In turn, these two ships were closely supported by the destroyers, which fought aggressively and resourcefully.

German Light Cruiser SMS Mainz sinking at the Battle of Heligoland Bight on 28th August 1914 in the First World War: picture by Willie Stoewer

• One of the two battle cruisers from the Humber, HMS Invincible, was to have an eventful and finally tragic war. An account of her experiences was written under the title ‘A Naval Digression’ by Gordon Findlay under the initials GF. GF wrote of the ship’s involvement in the Heligoland Bight battle: ‘The enemy tried to break away; evidently she hoped to escape in the mist, which was fast making the range of visibility very small. We took up the chase, dealing with the German Ariadne in our stride (she was left burning furiously, and in a sinking condition), and at 1.25pm again opened fire on the Koln. In ten minutes she was no more, and for the poor wretches on board those ten minutes must have been awful , as our squadron’s big guns literally raked her fore and aft; ‘twas little wonder that she so quickly caught fire, turned over and sank. Destroyers were sent on an errand of mercy, but not a single survivor could be seen.’ Invincible left the North Sea in November 1914 with HMS Inflexible, to confront Admiral Graf von Spee’s East Asia Squadron in the South Atlantic, sinking four of his ships at the Battle of the Falkland Islands on 8th December 1914. At the Battle of Jutland on 31st May 1916 HMS Invincible took a plunging shell in one of her magazines and exploded with the loss of all but six of her crew.

One of the surviving crew members from SMS Mainz (on the right), sunk in the Battle of Heligoland Bight on 28th August 1914 in the First World War being repatriated from Britain in 1917

• It is interesting to note that the approach of the British ships was given away by the increased radio traffic. The technique of radio silence was in its infancy, if used at all.

British submarine E14 sending the German wounded crew from V187 off with the bearing for Heligoland during the Battle of Heligoland Bight on 28th August 1914 in the First World War

• The commander of HMS E4, the British submarine that rescued the seamen from Defender’s boat and assisted the wounded German seamen from V187, was Lieutenant Commander Leir. Leir was notorious in the Royal Navy submarine service for pinching stores and had the nickname of Arch Thief. Leir was reputed to have appropriated three hundred tons of lead ballast while E4 was being built, leading the submarine to adopt the motto ‘We need no lead’. Leir is reputed to have taken items, including a fur lined leather flying jacket, from the stores at a Royal Naval Air Station after causing a diversion by setting off the fire alarm. Apparently the theft of naval stores was considered acceptable, provided the purpose was to improve the efficiency of the appropriator’s ship.

• One of the surviving officers from SMS Mainz, rescued and taken prisoner by a British ship, was Oberleutenant Wolfgang von Tirpitz, the son of Admiral von Tirpitz. Winston Churchill, First Lord of the Admiralty, sent notice to Admiral von Tirpitz that his son was safe.

References for the Battle of Heligoland Bight:

Naval Operations in the Great War Volume 1 by Sir Julian Corbett

Submarines and the War at Sea 1914-1918 by Richard Compton-Hall

Jane’s Fighting Ships of World War 1

A Naval Digression by GF

The previous battle in the First World War is the Battle of Étreux

The next battle in the First World War is the Battle of Néry