The Duke of Marlborough’s spectacular defeat of the hitherto invincible French army of Louis XIV on 2nd August 1704

Duke of Marlborough leads the attack at the Battle of Blenheim 2nd August 1704 in the War of the Spanish Succession: picture by Harry Payne

The previous battle in the British Battles series is the Battle of Worcester

The next battle in the War of the Spanish Succession is the Battle of Ramillies

To the War of the Spanish Succession index

Battle: Blenheim

War: Spanish Succession

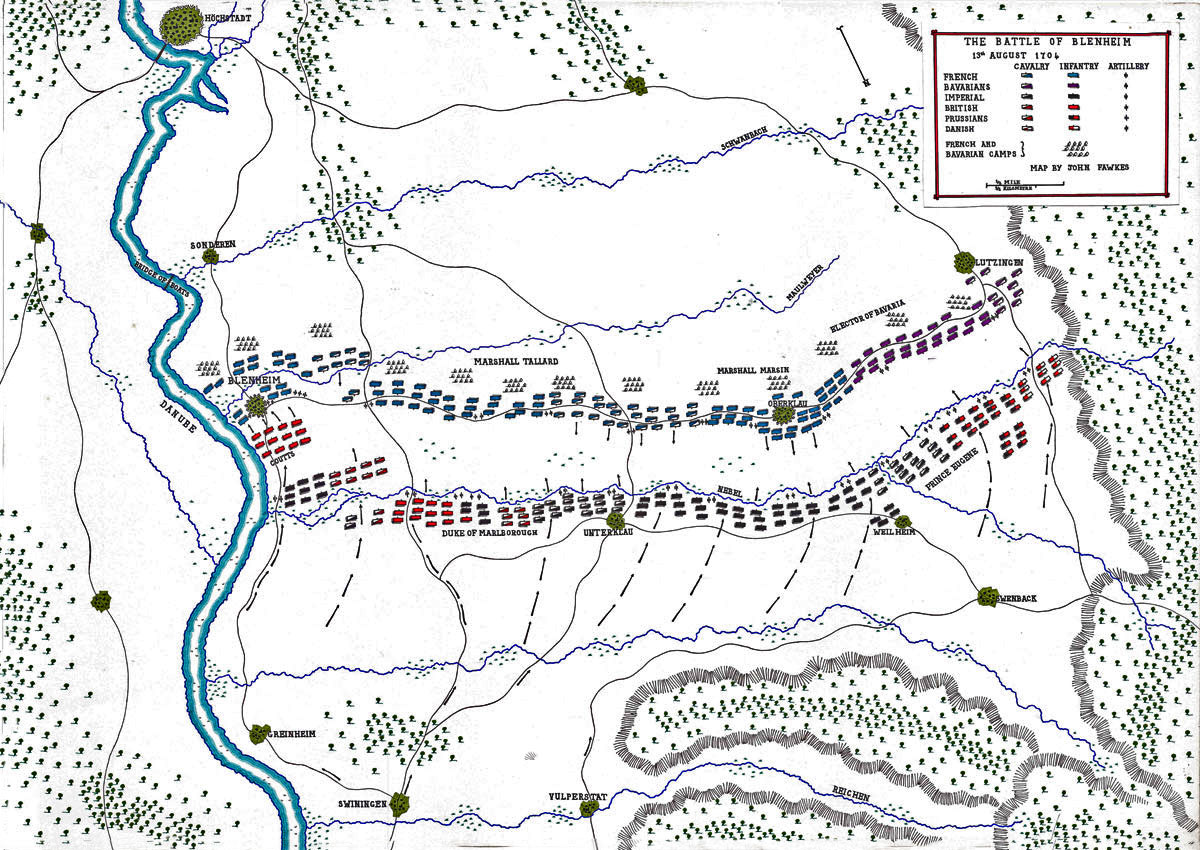

Date of the Battle of Blenheim: 2nd August 1704 (Old Style) (13th August 1704 New Style). The dates in this page are given in the Old Style. To translate to the New Style add 11 days

Place of the Battle of Blenheim: On the Danube in Southern Germany.

Combatants at the Battle of Blenheim: British, Austrians, Hungarians, Hanoverians, Prussians, Danes and Hessians against the French and Bavarians.

John Churchill Duke of Marlborough: Battle of Blenheim 2nd August 1704 in the War of the Spanish Succession

Generals at the Battle of Blenheim: The Duke of Marlborough and Prince Eugene of Savoy against Marshall Tallard, Marshall Marsin and the Elector of Bavaria.

Size of the armies at the Battle of Blenheim: There is considerable dissent on the size of the respective armies.

The French and Bavarian armies probably comprised 60,000 men (69 battalions of foot and 128 squadrons of horse) and around 60 guns. The Allied army comprised 56,000 men (51 battalions of foot and 92 squadrons of horse), of which 16,000 (14 battalions of foot and 18 squadrons of horse and dragoons) were British and 52 guns.

There is considerable variation in the numbers attributed to the French and Bavarian armies: some authorities put their strength as high as 72,000 men with 200 guns.

French sources quoted by Sullivan in his book “The Irish Brigades” give the relative strengths as:

French and Bavarians: 43,900 men, in 78 battalions and 127 squadrons, with 90 cannon.

British and Allies: 60,150 men in 66 battalions and 181 squadrons, with 66 cannon

(French battalions having 400 men to the Allied 500 and the French squadrons 100 to the Allied 150).

Uniforms, arms and equipment at the Battle of Blenheim:

The British Army of Queen Anne comprised troops of Horse Guards, regiments of horse, dragoons, Foot Guards and foot. In time of war the Department of Ordnance provided companies of artillery, the guns drawn by the horses of civilian contractors.

These types of formation were largely standard throughout Europe. In addition the Austrian Empire possessed numbers of irregular light troops; Hussars from Hungary and Bosniak and Pandour troops from the Balkans. During the 18th Century the use of irregulars spread to other armies until every European force employed hussar regiments and light infantry for scouting duties.

Horse and dragoons carried swords and short flintlock muskets. Dragoons had largely completed their transition from mounted infantry to cavalry and were formed into troops rather than companies as had been the practice in the past. However they still used drums rather than trumpets for field signals.

Infantry regiments fought in line, armed with flintlock musket and bayonet, orders indicated by the beat of drum. The field unit for infantry was the battalion comprising ten companies, each commanded by a captain, the senior company being of grenadiers. Drill was rudimentary and once battle began formations quickly broke up. The practice of marching in step was in the future.

French soldiers marching to join their regiment: Battle of Blenheim 2nd August 1704 in the War of the Spanish Succession: picture by Jean Anthoine Watteau

The paramount military force of the period was the French army of Louis XIV, the Sun King. France was at the apex of her power, taxing to the utmost the disparate groupings of European countries that struggled to keep the Bourbons on the western bank of the Rhine and north of the Pyrenees.

Marlborough and his British regiments acted as an uncertain mortar in keeping the edifice of the Imperial cause in Flanders intact.

Duke of Marlborough at the Battle of Blenheim 2nd August 1704 in the War of the Spanish Succession: Blenheim Palace Tapestry

The War of the Spanish Succession was an early outing for the new British Army established after the Restoration in 1685. The regiments that took the field were the forebears of powerful Victorian institutions; Foot Guards, King’s Horse, Royal Dragoons, Royal Scots, Buffs, Royal Welch Fusiliers, Cameronians, Royal Scots Fusiliers and several other prestigious corps.

Britain fell behind its continental enemies and allies in many respects. There was no formal military education for officers of the Army, competence coming from experience on the field of battle. Commissions in the horse, dragoons and foot were acquired by purchase, permitting the wealthy to achieve often unmerited promotion.

French Infantry on the march: Battle of Blenheim 2nd August 1704 in the War of the Spanish Succession: print after Jean Anthoine Watteau

Support services were not formally established and depended on the commander. A major contributing feature to the Duke of Marlborough’s success in the field was his concern that his soldiers be properly supplied and by his consummate ability to organise and administer that supply.

While every army had formal and explicit rank structures the realities of command and influence were still largely decided by social standing, particularly between armies of different nationality. It was a matter of necessity for John Churchill to have the status of Duke of Marlborough to enable him to exercise decisive influence over the fractious foreign officers he had to work with and over some of his own nationality. In reality his status as duke, while probably of greater significance than his military rank of Captain General, was insufficient to enable him to act as a true commander-in-chief rather than as quasi-chairman of a committee of Dutch, Austrian and British generals.

Marlborough’s cavalry attacks: Battle of Blenheim 2nd August 1704 in the War of the Spanish Succession: picture by John Wootton

The uniform of the British Regiments was the long red coat turned back at the lapels and cuffs to show the facings of the regimental colour; dark blue for guards and royal regiments; yellow, green, white or buff for many of the others. The Royal Horse Guards wore blue uniforms; as did the artillery, an organization not yet incorporated into the army proper.

Headgear was the tricorne hat, except for the company of grenadiers in each battalion of foot, the Horse Grenadier Guards, the Royal North British Dragoons (Scots Greys), the three regiments of fusiliers (Royal, Royal North British and Royal Welch) and the drummers of dragoons and foot, all of whom wore the mitre cap.

For the infantry a cross belt carried the cartridge case hanging on the right hip. A second cross belt carried the bayonet and hanger sword. Ammunition, carried in the cartridge case, comprised cartridges of paper wrap containing the ball and gunpowder.

Surrender of Marshal Tallard at the Battle of Blenheim 2nd August 1704 in the War of the Spanish Succession

Winner of the Battle of Blenheim: Decisively the army of the Duke of Marlborough and Prince Eugene.

British Regiments at the Battle of Blenheim:

King’s Regiment of Horse; later the King’s Dragoon Guards and now the 2nd Queen’s Dragoon Guards.

3rd Regiment of Horse; later the 3rd Carabineers and now the Royal Dragoon Guards.

5th Regiment of Horse; later the 5th Inniskilling Dragoon Guards and now the Royal Dragoon Guards.

6th Regiment of Horse; later the 3rd Carabineers and now the Royal Scots Dragoon Guards.

7th Regiment of Horse; later the 4th/7th Royal Dragoon Guards and now the Royal Dragoon Guards.

Royal North British Regiment of Dragoons, the Royal Scots Greys; now the Royal Scots Dragoon Guards.

5th Dragoons; later the 16th/5th Royal Lancers and now the Queen’s Royal Lancers.

1st Regiment of Foot Guards; now the Grenadier Guards.

The Royal Regiment; now the Royal Scots.

3rd Foot, the Buffs; now the Princess of Wales’s Royal Regiment.

8th King’s Foot; now the King’s Regiment.

10th Foot; later the Lincolnshire Regiment and now the Royal Anglian Regiment.

15th Foot; later the East Yorkshire Regiment and now the Prince of Wales’s Regiment of Yorkshire.

16th Foot; later the Bedfordshire Regiment and now the Royal Anglian Regiment.

Royal Irish; disbanded in 1922.

Royal Welch Fusiliers.

24th Foot; later the South Wales Borderers and now the Royal Regiment of Wales.

26th Foot, the Cameronians; later the Scottish Rifles, disbanded in 1968.

37th Foot: later the Royal Hampshire Regiment and now the Princess of Wales’s Royal Regiment.

Royal Artillery.

Officer of the 21st Royal Scots Fuzileers: Battle of Blenheim 2nd August 1704 in the War of the Spanish Succession: statuette by Pilkington Jackson

British Foot’s Order of Battle:

Row’s Brigade:

10th Foot

23rd Royal Welch Fusiliers

24th Foot

21st Royal North British Fuzileers

3rd Buffs

Hamilton’s Brigade:

8th King’s Foot

20th Foot

16th Foot

1st Battalion, 1st Royal Regiment

1st Foot Guards

Ferguson’s Brigade:

15th Foot

37th Foot

26th Foot

2nd Battalion, 1st Royal Regiment

Background to the Battle of Blenheim:

In November 1700 Charles II, King of Spain, died leaving his throne in his will to the Duke of Anjou, grandson to Louis XIV, King of France. Louis XIV permitted his grandson to accept the throne of Spain, thereby plunging Europe into a general war. The main antagonists were France and the Austrian Habsburg Empire, whose emperor would not stand by and see the Bourbons absorb Spain. The Low Countries, comprising Flanders and Holland, as in so many wars became one of the main theatres of military operations. The Dutch turned to Britain for troops and money under its treaty commitments and the British Army prepared to join its allies in the Low Countries.

In June 1702 John Churchill, Duke of Marlborough took up his appointment as commander-in-chief of the allied armies in Flanders. During the campaigns of 1702 and 1703 Marlborough grappled with the lack of co-operation from his Dutch allies and their apparent determination to avoid full-scale battle with the French armies attempting to overrun Flanders.

In 1704 Louis XIV turned away from the Low Countries. He intended this to be a year of overwhelming conquest for the French over the Austrian Hapsburgs. His plans saw the French commander, Marshall Villeroy assuming the defensive in Flanders as an army under Marshall Tallard advanced across the Rhine, another under Marshall Marsin and the Elector of Bavaria moved against the Hapsburgs from the Danube and the French army in Italy attacked through the Tyrol, thereby bringing Austria to her knees and suing for peace.

Consumed with anxiety over French intentions Marlborough took the field in April 1704, implementing his scheme to counter Louis XIV’s strategy by taking his army to Southern Germany. Drawing up his plans over the preceding winter and expecting the usual obstruction-the Dutch could be expected to put up fierce resistance to removing the army from the Low Countries-Marlborough revealed his full intentions to only a select few.

In May 1704 Marlborough began his march south. In early June 1704 he halted in southern Germany to allow his various forces to catch him up; his brother Charles Churchill with the British infantry, Prince Lewis of Baden with the Hessians, Hanoverians and Prussians and Prince Eugene of Savoy with the Imperial troops. Prince Eugene marched on to block any French attempt to cross the Rhine while Marlborough and Prince Lewis moved against the Elector of Bavaria, positioned on the Danube and barring entry into his country.

On 21st June 1704 British and allied troops stormed the position known as the Schellenburg held by the French and Bavarians, forcing the Elector to retire into the fortified city of Augsburg.

The French general Marshall Tallard marched south to reinforce the Bavarian and French troops, meeting the Elector north of Augsburg. Prince Eugene hurried to join Marlborough on the Danube, arriving at Hochstadt. These generals made their rendez-vous on 26th July 1704.

British Engineer Officer: Battle of Blenheim 2nd August 1704 in the War of the Spanish Succession: picture by Richard Simkin

On 29th July 1704 Prince Eugene received the alarming news that the French and Bavarian armies were crossing the Danube some three miles to the west of his position. He hurriedly moved east to the Kessel River, a tributary of the Danube, sending urgent requests for support to Marlborough, still marching up to the south bank of the Danube.

On 31st July 1704 Marlborough’s army crossed the Danube at Donauworth, turned west to cross the Wornitz and marched to join Prince Eugene on the Kessel tributary of the Danube. The combined army of Marlborough and Prince Eugene was now some 5 miles short of the French and Bavarians.

Tallard’s army held a position stretching north from the village of Blenheim on the Danube. Tallard, Marsin and the Elector had no expectation that Marlborough and Prince Eugene would seek battle against their more powerful army, well positioned behind the marshy Nebel, with its flanks secured by the Danube and the fortified village of Blenheim on the right and the fortified village of Lutzingen and rising hills on the left. Their expectation was that the British and their allies as they ran short of supplies would retire north without a fight. Marlborough and Prince Eugene planned otherwise.

The axis of Tallard’s position was Blenheim with its garrison of 26 battalions and 12 squadrons. Marsin and the Elector concentrated the strength of their separate army protecting the villages of Lutzingen and Oberglau; 22 battalions and 36 squadrons masking Lutzingen on the far left. Positioned forward of the line the hamlet of Oberglau was held by 14 battalions including the three Irish regiments in the French service. Between Oberglau and Blenheim, where the division fell between Tallard’s army and the army of Marsin and the Elector, lay 80 squadrons of horse and 7 battalions of foot.

If an attack had been expected it may be that more troops would have been moved out of the villages into the intervening ground. The lack of infantry and a unified command at this point was to prove fatal for the French and Bavarians.

Map of the Battle of Blenheim 2nd August 1704 in the War of the Spanish Succession: map by John Fawkes

Account of the Battle of Blenheim:

On the evening of 1st August 1704 the Duke of Marlborough and Prince Eugene studied the terrain between the armies from a church steeple. They saw that the ground was cut by a number of tributary streams flowing North West to South East into the Danube and that the village of Blenheim lay beyond the point where one of the streams, the Nebel joined the main river. The French and Bavarian troops were encamped on the ground behind the Nebel between Blenheim and Lutzingen, a distance of some 2½ miles. The road from Donauworth to Dillingen passed through Blenheim, crossing the Nebel by a stone bridge now partly destroyed.

At 2am on 2nd August 1704 the British and their allies broke camp, crossed the Kessel stream in eight columns and began their advance against the French and Bavarians. Once on the plain the army formed up with the cavalry in the centre and the infantry on the flanks, the ground by the river being unsuitable for mounted action. The artillery column wound its way along the highway.

With one third of the approach march completed a further column of infantry formed on the bank of the Danube comprising among other nationalities 14 British battalions. Command of this column fell to Lord Coutts.

16th Foot advances to attack Blenheim: Battle of Blenheim 2nd August 1704 in the War of the Spanish Succession

As Marlborough’s army approached the French lines Prince Eugene marched his Imperial contingent away to the right to make his attack on the Elector’s Bavarians.

At around 6am the first skirmishes of the battle took place with the French pickets driven in. It was a foggy morning and in spite of the fights between the cavalry vedettes Marshall Tallard remained convinced that Marlborough was on the march north to restore his lines of communications, not seeking a general action. Many of the French and Bavarian cavalry regiments were dispersed across the countryside on the perennial chore of gathering forage for their horses.

Brigadier Rose’s brigade advances: Battle of Blenheim 2nd August 1704 in the War of the Spanish Succession

At 7am the fog lifted revealing to the French commanders the attacking army deployed on the far side of the Nebel River, just half a mile distant. Drums beat, trumpets sounded and the cavalry foragers were hastily recalled as the regiments formed up and the artillery bombardment began.

“Salamander” Coutts’ column of British and German foot moved forward on the extreme left, preparing to attack Blenheim while in the centre Marlborough’s engineer officers repaired the stone bridge over the Nebel and threw five pontoon bridges across the stream for the passage of the attacking columns.

Duke of Marlborough and the Earl of Cadogan at the Battle of Blenheim 2nd August 1704 in the War of the Spanish Succession: picture by Pieter van Bloemen

Coutts advanced with his contingent in six lines; Row’s British Brigade followed by a brigade of Hessians, Ferguson’s British Brigade, a brigade of Hanoverians and two further lines of foot. Marlborough deployed the rest of his force away to the centre and right in four lines; foot, cavalry, foot and then again cavalry.

On the extreme right Prince Eugene hurried to complete his extended deployment against the Bavarian flank, finding his movement impeded by the irregular nature of the ground.

At 8am the French artillery opened fire returning the bombardment from the British and German guns. Marlborough waited impatiently for news that Prince Eugene’s Imperial troops were in place so the attack could begin.

French supply column: Battle of Blenheim 2nd August 1704 in the War of the Spanish Succession: picture by Jean Anthoine Watteau

At 12.30pm Prince Eugene reported that he was in place and ready and Marlborough ordered Coutts to assault Blenheim. By 1pm Row’s Brigade of 1st Guards, 10th Foot, 21st Foot, 23rd Royal Welch Fusiliers and 24th Foot were advancing on the village under heavy fire. The British Foot was ordered not to return the fire, so as not to delay the advance, until the brigadier himself struck the first fortification. The Foot was then to storm the village at the point of the bayonet.

Memorably Brigadier Row stuck his sword into the wooden barricade and was promptly shot down together with his staff and around one third of his battalions. As the remnant of the brigade fell back they were charged in flank by the French Gens D’Armes, who were in turn repelled by the following Hessians.

At Coutt’s request five squadrons of British Horse and Dragoons came up on his left, struggling across the Nebel and repulsed the Gens D’Armes with a charge.

First Foot Guards advance to attack Blenheim: Battle of Blenheim 2nd August 1704 in the War of the Spanish Succession

Ferguson’s British Brigade of Foot resumed the advance with the remnants of Row’s Brigade. Storming into the outskirts of Blenheim they engaged in hand to hand fighting with the French Foot but were unable to make further progress into the village.

On the right centre the Prince of Holstein-Beck launched his infantry assault in the direction of the fortified village of Oberglau. Holstein-Beck led forward the German Brigades of Wulwen and Heigdenbregh, but had considerable difficulty crossing the Nebel stream, here closely defended by French Foot positioned behind the stream, well forwarded of the main French position in Oberglau. Four battalions managed to cross the Nebel including Benheim’s and Goor’s Regiments, only to be attacked by several battalions of foot from the Oberglau garrison. The two German regiments were nearly annihilated.

Conducting the assault were Irish Regiments in the French service (the battalions of Lee, Dorrington and Lord Clare) with the French Regiments of Champagne and Bourbonnois. The Prince of Holstein-Beck was severely wounded and some 2,000 Allied soldiers captured during the attempted assault on Oberglau.

No real progress was made in taking Oberglau and the hamlet held out until the collapse of Tallard’s army brought about the precipitate retreat of the French and Bavarian left wing.

Further to the Allied right Prince Eugene struggled to maintain his position against the Elector of Bavaria, three vigorous attacks being beaten back by the Bavarian troops, also positioned well forward on the edge of the Nebel River.

In the centre of the battlefield Marlborough’s main force crossed the Nebel, the first line of foot followed by a second line of cavalry. Tallard launched his horse on the British cavalry, disordered after the troublesome river crossing. The British were relieved by the counter attack of the Prussian cavalry of General Bothmar, driving the French back from the stream.

26th Foot ‘the Cameronians’ advance to attack Blenheim: Battle of Blenheim 2nd August 1704 in the War of the Spanish Succession

In spite of the setbacks in the attacks on Blenheim, Oberglau and Lutzingen, the French and Bavarians in the three villages were contained sufficiently to enable Marlborough to bring the whole of his cavalry force across the Nebel and launch them at the French troops positioned in the open ground between Blenheim and Lutzingen, the site of the join between Tallard’s and Marsin’s commands. Marsin’s regiments fell back towards their infantry in Oberglau leaving Tallard’s force isolated and exposed. In the face of a further mass charge by Marlborough’s squadrons, Tallard’s cavalry fled behind Blenheim and on towards the River Danube. In the confusion Marshall Tallard was wounded and captured and many of his men drowned in their attempt to escape across the Danube. Marsin and the Elector, witnessing the collapse of Tallard’s army set fire to Oberglau and Lutzingen and retreated precipitously to the North West.

Surrender of Marshal Tallard at the Battle of Blenheim 2nd August 1704 in the War of the Spanish Succession: Blenheim Palace Tapestry

Marlborough’s troops swept around the rear of Blenheim surrounding the large French garrison. Charles Churchill, Marlborough’s brother was preparing to assault the village when the French proposed a parley. The French sought terms that would enable their regiments to leave with honour but only complete submission was acceptable and 24 battalions of French Foot with 4 regiments of dragoons surrendered to Marlborough, the Regiment of Navarre burning its colours rather than deliver them to the British.

The overthrow of the French and Bavarian army was absolute.

Duke of Marlborough signing his dispatch to Queen Anne:Battle of Blenheim 2nd August 1704 in the War of the Spanish Succession

Casualties at the Battle of Blenheim: Total allied losses were 12,000 killed and wounded. Of these, British casualties were 200 officers and 2,000 soldiers. French and Bavarian casualties were 40,000 killed, wounded and captured. Marshall Tallard went into captivity in England. The French lost 11,000 prisoners, including 2 generals, most of their guns, 129 colours, 171 cavalry standards and the whole of their camp.

Follow-up to the Battle of Blenheim: The immediate result of Blenheim was the collapse of Louis XIV’s assault on Austria. The war continued for some years in Flanders, but Louis XIV’s grand strategy was thwarted.

Regimental anecdotes and traditions of the Battle of Blenheim:

- At the order of Queen Anne a medal was struck to commemorate the battle.

- An inn-keeper in England greeted the captive Marshall Tallard with the words “Welcome sir. We have another room prepared here for your master.”

- The house built by the Duke of Marlborough at Woodstock in Oxfordshire is named Blenheim Palace after the battle.

- One of the regiments in Brigadier Row’s brigade was his own regiment, the Royal North British Fusiliers (21st Foot-later the Royal Scots Fusiliers). When Row fell, shot down as he stuck his sword in the French ramparts, his two field officers, Lieutenant Colonel Dalzell and Major Campbell, rushed to his assistance only themselves to be killed. The regiment lost all three senior officers along with an unknown number of other officers and soldiers.

- See the British Battles blog on the tapestries commemorating the Duke of Marlborough’s victories during the War of the Spanish Succession at Blenheim Palace.

References for the Battle of Blenheim:

- Marlborough as military commander by David Chandler

- Fortescue’s History of the British Army Volume 1.

- Creasy’s Fifteen Decisive Battles of the World.

- Sullivan’s Irish Brigades in the Service of France.

The previous battle in the British Battles series is the Battle of Worcester

The next battle in the War of the Spanish Succession is the Battle of Ramillies

To the War of the Spanish Succession index