The battle fought on 27th July 1880, where a force of British and Indian troops was overwhelmed by Afghan soldiers and tribesmen, a notorious Victorian military disaster

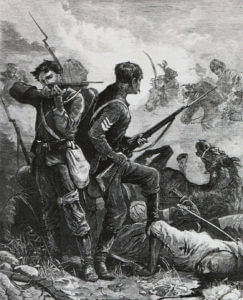

Last stand of the ‘Eleven’ from the 66th Regiment at the Battle of Maiwand on 27th July 1880 in the Second Afghan War: picture by Harry Payne

The previous battle in the Second Afghan War is the Battle of Ahmed Khel

The next battle in the Second Afghan War is the Battle of Kandahar

To the Second Afghan War index

Mohammad Ayoub Khan, Afghan commander at the Battle of Maiwand on 27th July 1880 in the Second Afghan War

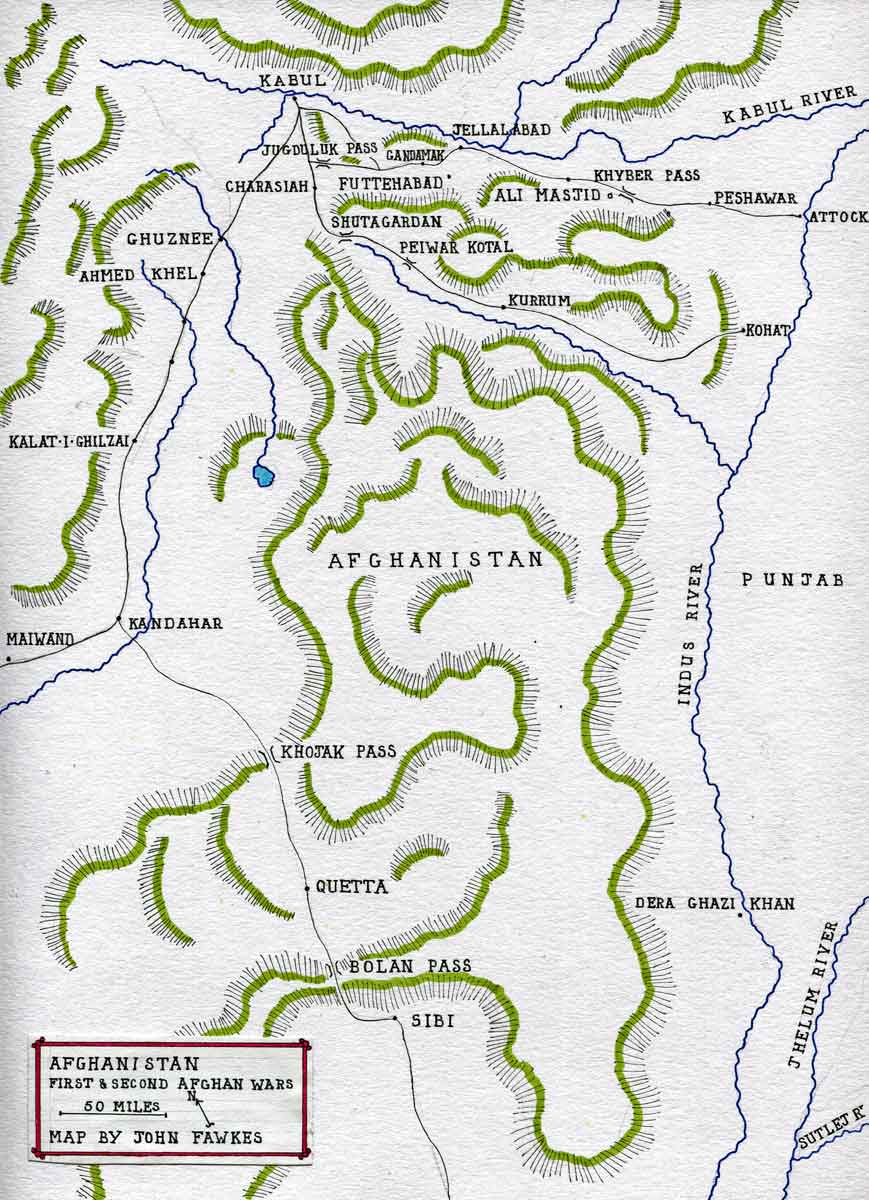

Battle: Maiwand

War: Second Afghan War

Date of the Battle of Maiwand: 27th July 1880.

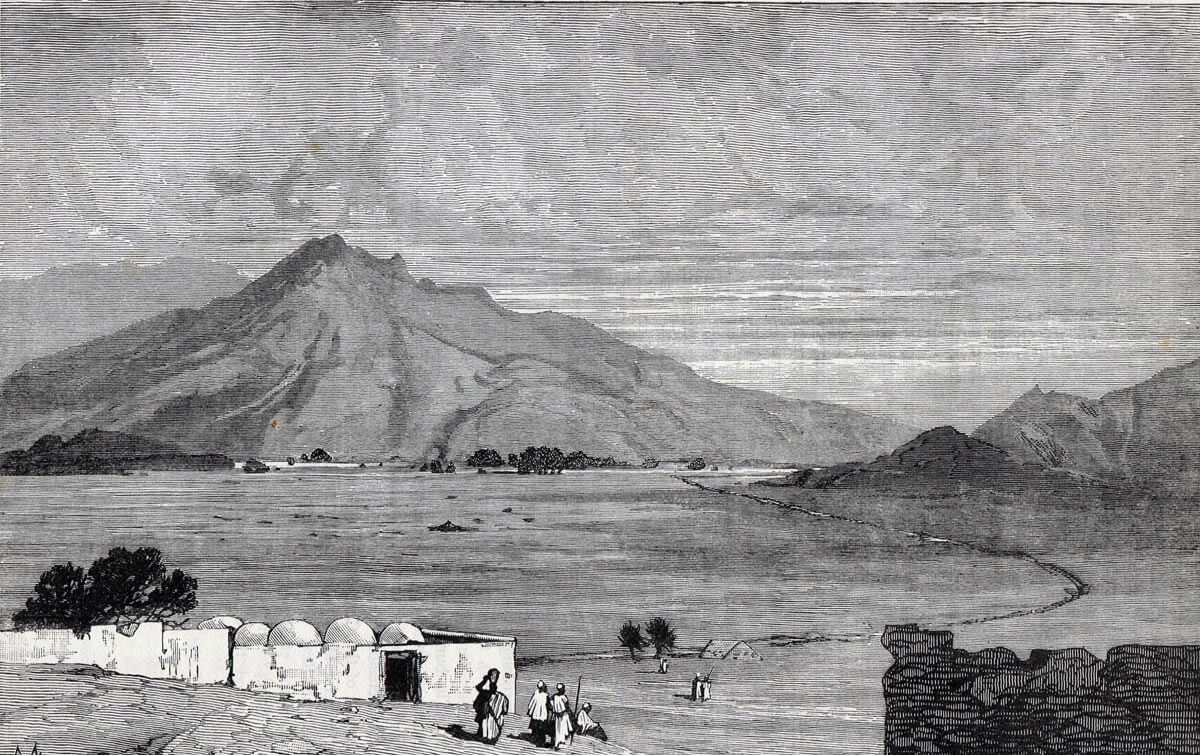

Place of the Battle of Maiwand: West of Kandahar in Southern Afghanistan.

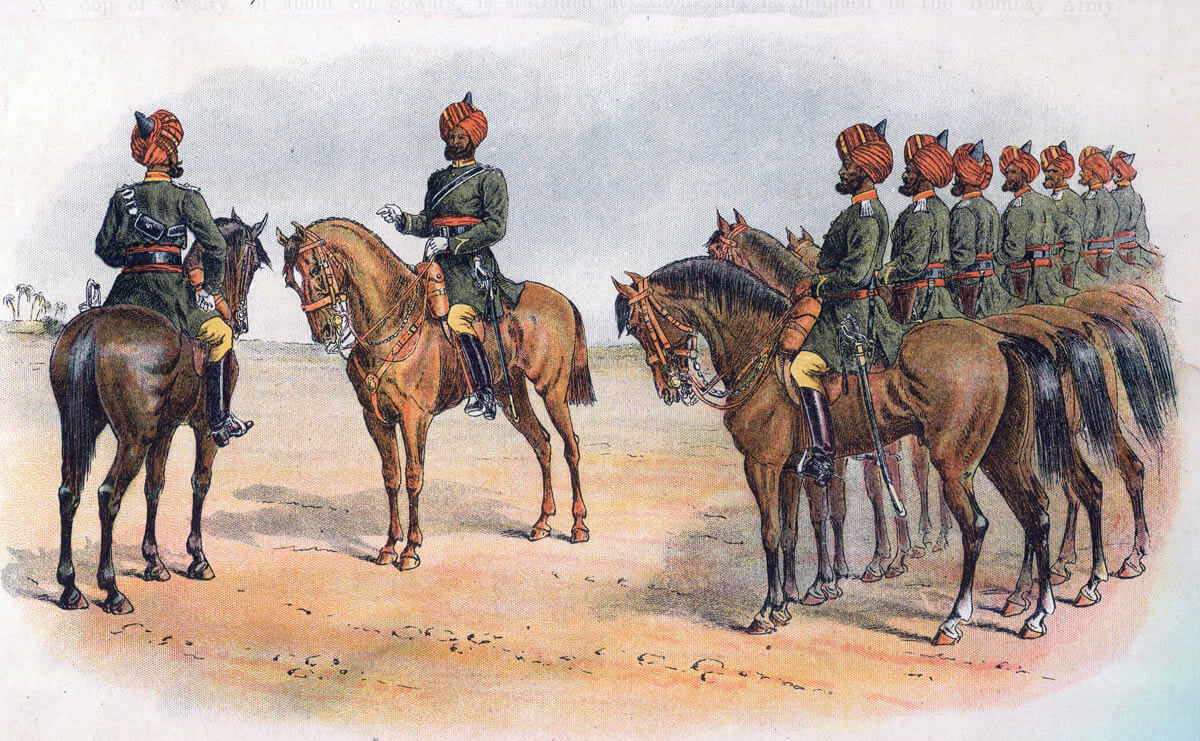

Combatants at the Battle of Maiwand: British troops and Indian troops of the Bombay Army against Afghan regular troops and tribesmen.

Generals at the Battle of Maiwand: Brigadier General Burrows against Ayub Khan.

Size of the armies at the Battle of Maiwand: 2,500 British and Indian troops with 6 RHA guns and 6 smooth bore guns against 3,000 Afghan cavalry and 9,000 infantry with 6 batteries of artillery (36 guns).

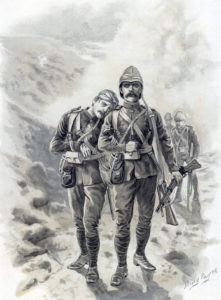

Bombay Grenadiers: Battle of Maiwand on 27th July 1880 in the Second Afghan War: picture by A.C. Lovett

Uniforms, arms and equipment at the Battle of Maiwand:

The British and Indian forces were made up, predominantly, of native Indian regiments from the armies of the three British presidencies, Bengal, Bombay and Madras, with smaller regional forces, such as the Hyderabad contingent, and the newest, the powerful Punjab Frontier Force.

The Mutiny of 1857 had brought great change to the Indian Army. Prior to the Mutiny, the old regiments of the presidencies were recruited from the higher caste Brahmins, Hindus and Muslims of the provinces of central and eastern India, principally Oudh. Sixty of the ninety infantry regiments of the Bengal Army mutinied in 1857 and many more were disbanded, leaving few to survive in their pre-1857 form. A similar proportion of Bengal Cavalry regiments disappeared.

The British Army overcame the mutineers with the assistance of the few loyal regiments of the Bengal Army and the regiments of the Bombay and Madras Presidencies, which, on the whole, did not mutiny. But principally, the British turned to the Gurkhas, Sikhs, Muslims of the Punjab and Baluchistan and the Pathans of the North-West Frontier for the new regiments with which Delhi was recaptured and the Mutiny suppressed.

66th Regiment in England before leaving for India: Battle of Maiwand on 27th July 1880 in the Second Afghan War: picture by Harry Payne

After the Mutiny, the British developed the concept of ‘the Martial Races of India’. Certain Indian races were more suitable to serve as soldiers, went the argument, and those were, coincidentally, the races that had saved India for Britain. The Indian regiments that invaded Afghanistan in 1878, although mostly from the Bengal Army, were predominantly recruited from the martial races; Jats, Sikhs, Muslim and Hindu Punjabis, Pathans, Baluchis and Gurkhas.

Prior to the Mutiny, each Presidency army had a full quota of field and horse artillery batteries. The only Indian artillery units allowed to exist after the Mutiny were the mountain batteries. All the horse, field and siege batteries were, from 1859, found by the British Royal Artillery.

In 1878, the regiments were beginning to adopt khaki for field operations. The technique for dying uniforms varied widely, producing a range of shades of khaki, from bottle green to a light brown drab.

As regulation uniforms were unsatisfactory for field conditions in Afghanistan, the officers in most regiments improvised more serviceable forms of clothing.

Every Indian regiment was commanded by British officers, in a proportion of some 7 officers to 650 soldiers, in the infantry. This was an insufficient number for units in which all tactical decisions of significance were taken by the British and was particularly inadequate for less experienced units.

Lieutenant McLaine bringing out the guns at the Battle of Maiwand on 27th July 1880 in the Second Afghan War: picture by Stanley L. Wood

The British infantry carried the single shot, breech loading, .45 Martini-Henry rifle. The Indian regiments still used the Snider; also a breech loading single shot rifle, but of older pattern and a conversion of the obsolete muzzle loading Enfield weapon.

The cavalry was armed with sword, lance and carbine, Martini-Henry for the British troopers, Snider for the Indian sowars.

The British artillery, using a variety of guns, many smooth bored muzzle loaders, was not as effective as it could have been, if the authorities had equipped it with the breech loading steel guns being produced for European armies. Artillery support was frequently ineffective and on occasions the Afghan artillery proved to be better equipped than the British.

The army in India possessed no higher formations above the regiment in times of peace, other than the staffs of static garrisons. There was no operational training for staff officers. On the outbreak of war, brigade and divisional staffs had to be formed and learn by experience.

The British Army had, in 1870, replaced long service with short service for its soldiers. The system was not yet universally applied, so that some regiments in Afghanistan were short service and others still manned by long service soldiers. The Indian regiments were all manned by long service soldiers. The universal view seems to have been that the short service regiments were weaker both in fighting effectiveness and disease resistance than the long service.

Winner of the Battle of Maiwand: Overwhelmingly, the Afghans.

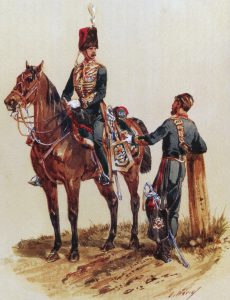

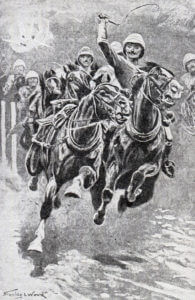

Royal Horse Artillery on exercise in England: Battle of Maiwand on 27th July 1880 in the Second Afghan War: picture by Orlando Norie

British and Indian Regiments at the Battle of Maiwand:

E/B Battery, Royal Horse Artillery, now Maiwand Battery, 29th Commando Regiment, Royal Artillery.

3rd Queen’s Own (Bombay Cavalry)

3rd Scinde Horse (Bombay Army)

HM 66th Regiment (less 2 companies), from 1882 Royal Berkshire Regiment and now the Rifles.

1st Grenadiers (Bombay Army)

30th Bombay Native Infantry (Jacob’s Rifles)

2nd Company Bombay Sappers and Miners (half company)

Account of the Battle of Maiwand:

When in March 1879 Lieutenant General Sir Donald Stewart marched north to Kabul with his division of Bengal Army and British regiments, Kandahar was left to the Wali, its Afghan ruler, and a replacement garrison of Bombay and British troops under Major General Primrose. The Bengal regiments in the north of Afghanistan were to withdraw to India during 1880, leaving only Kandahar Province occupied by British and Indian troops.

In early 1880, the word reached Kandahar that Ayub Khan, the younger brother of the deposed Ameer of Afghanistan Yakoub Khan, was about to march with his army from Herat to Ghuznee, passing to the north of Kandahar.

The Wali of Kandahar urged the British to intercept Ayub at Girishk, on the Helmond River, to prevent him from raising the whole countryside by his armed passage.

The Indian Government directed General Primrose to send a brigade to Girishk and to bring regiments up from the reserve division as replacements.

Primrose appointed Brigadier General Burrows commander of the field brigade, with Brigadier General Nuttall commanding the cavalry.

The two cavalry regiments, 3rd Bombay Light Cavalry and 3rd Scinde Horse marched out of Kandahar on 4th July 1880, followed by the infantry and guns the next day.

Burrows force joined the Wali’s troops at Girishk, only for the Wali’s men to mutiny, many joining Ayub Khan’s army. The British seized their six antiquated smooth bore guns and formed a makeshift battery, manned by soldiers from the 66th Regiment with Royal Horse Artillery officers under Captain Slade.

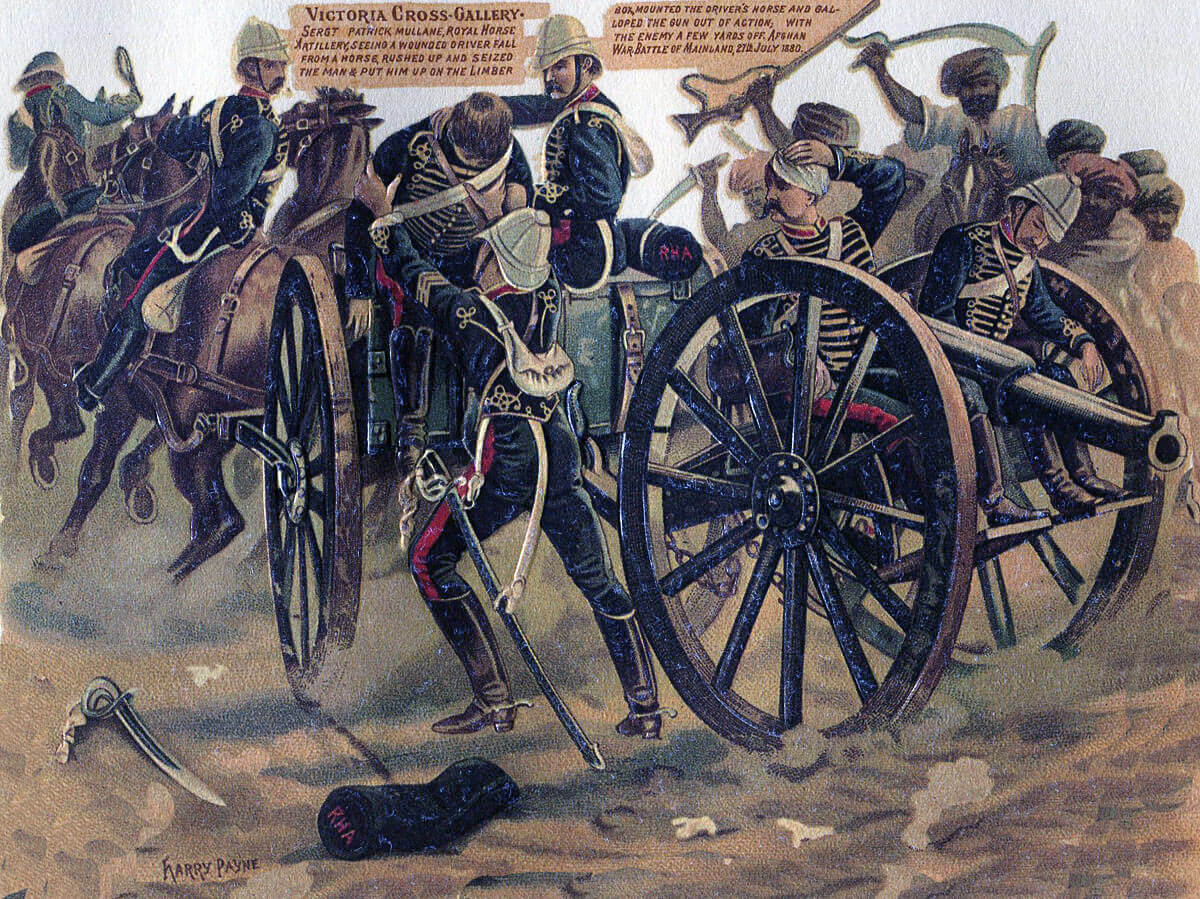

Saving the guns: E/B Battery Royal Horse Artillery at the Battle of Maiwand on 27th July 1880 in the Second Afghan War: picture by Richard Caton Woodville

Late on 26th July 1880, Burrows received intelligence that Ayub’s force was moving through the Malmund Pass and would reach the village of Maiwand the next day, poised to march on Ghuznee. If Burrows had moved on hearing the news, he might have reached Maiwand before Ayub. Instead the brigade marched in the early hours of the next day, after a particularly trying time assembling its baggage.

As the British/Indian brigade approached Maiwand, Ayub’s army could be seen marching across its front, in the swirling dust storms that swept the semi-desert area. Burrows formed the view that he could reach Maiwand before the Afghans and urged his troops forward.

Colonel Galbraith and the 66th Regiment at the Battle of Maiwand on 27th July 1880 in the Second Afghan War

Burrows force passed the village of Mundabad and found it had reached a substantial ravine twenty-five feet deep, running along its front. Instead of taking up defensive positions along the ravine and in the village, Burrows ordered his force across the ravine into the open plain beyond.

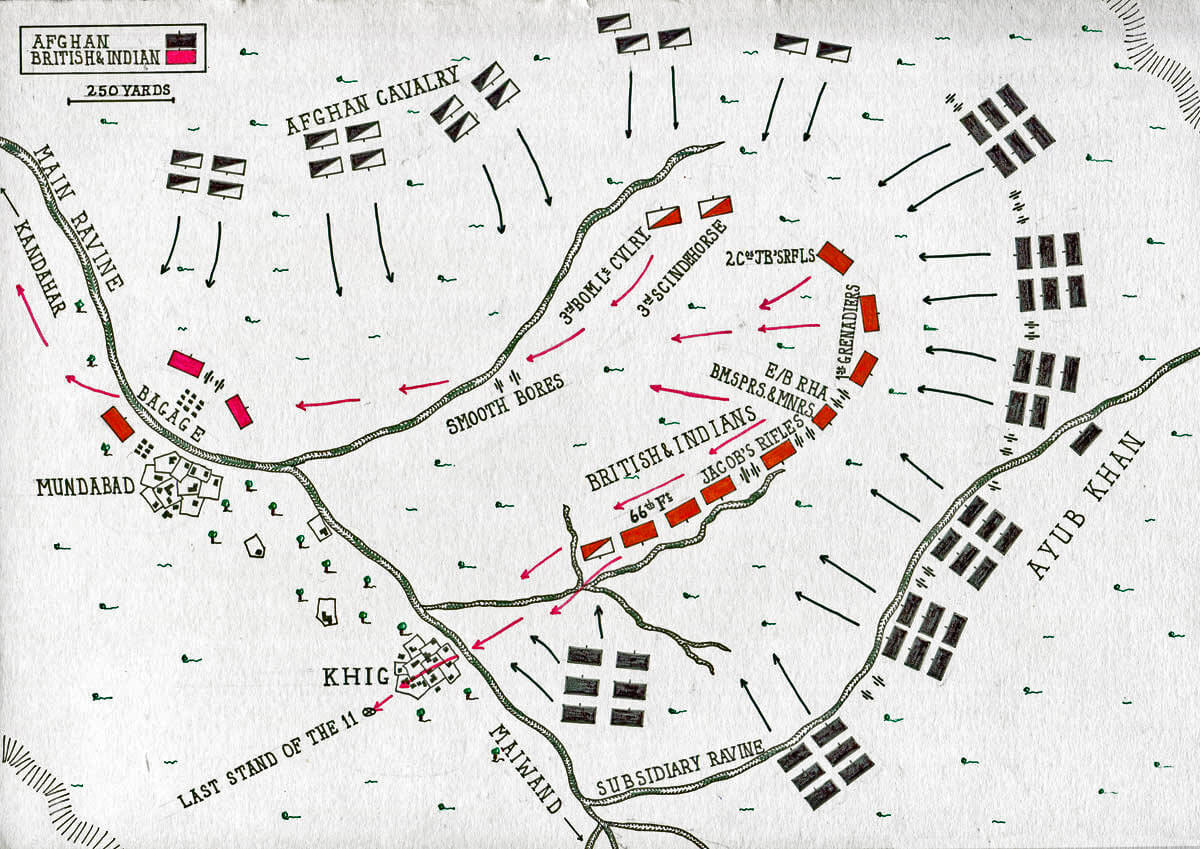

Ayub’s army comprised regular Afghan regiments from Kabul and Herat, the Wali’s force which had deserted to him and Afghan tribesmen, making the force up to around 12,000 men, including 3,000 cavalry. Burrows, by contrast, had available for his line around 1,500 infantry and 350 cavalry, after telling off the necessary baggage guards.

The British guns crossed the ravine and continued forward to a position where the Afghans were in range and opened fire.

The guns advanced considerably further than Burrows intended, the rest of his force hurrying up in support; the infantry in a line, with the 66th on the right, Jacob’s Rifles in the centre and the 1st Grenadiers on the left.

Saving the guns at the Battle of Maiwand on 27th July 1880 in the Second Afghan War: picture by James Prinsep Beadle

The first phase of the battle comprised an artillery duel; the Afghans out-shooting the British, having a greater number of more modern and heavier guns, including six state-of-the-art Armstrong guns. The 1st Grenadiers and the cavalry suffered significant casualties, while the 66th and Jacob’s Rifles were able to find cover from the bombardment.

Following the artillery exchange, the Afghan infantry massed in front of the British/Indian line for an assault. In a pre-emptive move, Burrows ordered the 1st Grenadiers to attack, but then cancelled the order even though the advance was making progress, fearing that the Grenadiers were suffering excessive casualties from the Afghan gunfire.

Saving the wounded at the Battle of Maiwand on 27th July 1880 in the Second Afghan War: picture by Lady Butler

The advance across the open plain exposed the British/Indian left flank; the threat from the enveloping Afghan cavalry causing Burrows to move two companies of Jacob’s Rifles to this flank and bolstering them with two of the smooth bore guns on their left, between Jacob’s Rifles and the troops of the baggage guard.

The British commanders had not realized that a hidden second ravine ran beside the force’s other flank, joining the main ravine in their right rear. The Afghans used this ravine during the battle to infiltrate down the British/Indian right flank, forcing the 66th Foot to wheel to face the Afghans, until the regiment faced at right angles to its neighbours, Jacob’s Rifles and the 1st Bombay Grenadiers.

‘Bobbie the Dog’ of the 66th Regiment, wearing his Afghan campaign medal ribbon: Battle of Maiwand on 27th July 1880 in the Second Afghan War

Burrows’ force was now seriously strung out, in a horse shoe formation, exposed by the abortive advance of the infantry line, with the Afghan cavalry massing on the left flank and Afghan tribesmen, infantry and guns infiltrating down the right flank, by way of the subsidiary ravine.

In the early afternoon, the two smoothbore guns ran out of ammunition and withdrew, a move which severely unsettled the two companies of Jacobs Rifles on the left flank, already suffering from the artillery fire and the heat.

With the departure of the smooth bores, the Afghan cavalry were enabled to infiltrate behind the British/Indian left flank. Efforts were made to counter this move with volley firing from the two companies of Jacob’s Rifles, but the fire was largely ineffective, the companies inexperienced and commanded by a newly joined officer, almost unknown to his soldiers and who did not speak their language.

On the British/Indian right flank, the Afghans continued to pass down the subsidiary ravine. A move was made by troops of the Scinde Horse to attack these Afghans but the cavalry was recalled.

Ayub brought two of his guns down the subsidiary ravine and commenced firing at short range, probably as short as three hundred metres, into the 1st Grenadiers.

In the early afternoon, the guns ceased firing and a mass of Afghan tribesman charged the British/Indian infantry line. The two companies of Jacob’s Rifles on the left fled, leaving the flank of the 1st Grenadiers wholly exposed.

The Afghans cut down numbers of the Grenadiers, the Indian soldiers apparently too exhausted and demoralized to resist.

The RHA guns positioned in the centre of the line fired a last salvo and withdrew in haste, the Afghans reaching within yards of the retreating guns and overwhelming the left section. Seeing the guns go, the remainder of Jacob’s Rifles dissolved into the left wing of the 66th, throwing the right of the line into confusion.

Burrows sent Nuttall an order to charge the Afghans with his cavalry, in an attempt to restore the situation. Only 150 cavalry sowars could be assembled and these men charged half-heartedly at the Afghans surrounding the Grenadiers and withdrew immediately after the contact. Burrows rode about the field attempting to bring about a further cavalry attack, but without success.

66th Regiment and E/B Battery Royal Horse Artillery at the beginning of the Battle of Maiwand on 27th July 1880 in the Second Afghan War: picture by Richard Caton Woodville

Lieutenant Charles William Hinde, Adjutant of 1st Bombay Grenadiers, killed at the Battle of Maiwand on 27th July 1880 in the Second Afghan War

The British guns fired from a position to the rear of the infantry and were then forced to withdraw across the main ravine, coming into action several times from positions further back.

The infantry fell back in two separate directions, the left wing retreating towards Mundabad, the right, comprising the 66th, the Sappers and Miners and most of the Grenadiers pushed towards the village of Khig. Many of the Grenadiers were killed during the retreat to the main ravine. The 66th, broken up by the collapse of the two Indian regiments, fell back in small fighting groups.

The 66th and the Grenadiers, pursued by large numbers of Afghans, crossed the ravine into Khig, where around a hundred officers and men made a stand in a garden on the edge of the village. Overwhelmed, the survivors withdrew through Khig, with a second stand in a walled garden. The final stand was made by eleven survivors of the 66th outside the village, 2 officers and 9 soldiers.

The remnant of the army was enabled to leave the field, the right wing of the Afghan army held off by the surviving companies of the Grenadiers, fighting until their ammunition was exhausted and then overwhelmed.

Last stand of the ‘Eleven’ at the Battle of Maiwand on 27th July 1880 in the Second Afghan War: picture by Frank Feller

Burrows, the British commander, made his way through Khig, giving up his horse to a wounded officer and being rescued by a warrant officer of the Scinde Horse, unaware that the remnant of his infantry right wing was fighting to the death behind him.

The escaping British and Indian troops and camp followers streamed up the road towards Kandahar, pursued by the Afghan cavalry. During the disorganized retreat, the pursuing Afghans were held off by a squadron of the Scinde Horse, the RHA battery and the infantry from the baggage guard, although many stragglers were caught and killed, particularly the wounded.

The Afghans on foot were distracted by the resistance in Khig and by the Grenadiers and the opportunity to loot the British and Indian baggage.

The survivors of the brigade struggled on towards Kandahar, until they were met by a small relieving force and the Afghan cavalry withdrew.

‘The Eleven’, the last stand of the 66th Regiment with Bobbie the dog at the Battle of Maiwand on 27th July 1880 in the Second Afghan War

Casualties at the Battle of Maiwand: The British and Indian force lost 21 officers and 948 soldiers killed. 8 officers and 169 men were wounded. The Grenadiers lost 64% of their strength and the 66th lost 62%, including 12 officers. The cavalry losses were much smaller.

A reliable estimate of Afghan casualties is 3,000, reflecting the desperate nature of much of the fighting.

Regimental casualties at the Battle of Maiwand:

E/B Battery, Royal Horse Artillery: 14 dead and 13 wounded

3rd Queen’s Own (Bombay Cavalry) 27 dead and 18 wounded

3rd Scinde Horse (Bombay Army) 15 dead and 1 wounded

HM 66th Regiment 286 dead and 32 wounded

1st Grenadiers 366 dead and 61 wounded

30th Bombay NI (Jacob’s Rifles) 241 dead and 32 wounded

2nd Company Bombay Sappers and Miners 16 dead and 6 wounded

Follow-up to the Battle of Maiwand: The Afghan victory led Ayub Khan to abandon his march on Ghuznee and lay siege to Kandahar. In spite of the losses at Maiwand, the British and Indian garrison was sufficient to resist until the arrival of General Roberts with a force from Kabul and the final battle of the war.

Anecdotes and traditions from the Battle of Maiwand:

Queen Victoria presenting campaign medals to soldiers of the 66th and to ‘Bobbie the Dog’: Battle of Maiwand on 27th July 1880 in the Second Afghan War

- Maiwand illustrated the knife-edged nature of the battles in Afghanistan: heavily outnumbered British and Indian forces winning against much larger forces of Afghans, provided they were experienced troops led by competent commanders. Although undoubtedly brave, Burrows had not commanded in battle and had no experience of commanding a mixed force of infantry, cavalry and guns. He permitted his force to advance into an exposed position and failed to press home the attack that might have retrieved the situation. At Ahmed Khel, General Stewart came close to disaster at the hands of an Afghan army with no guns. At Maiwand the Afghans had an overwhelming advantage in gun numbers and quality and in Jacob’s Rifles, one third of his infantry strength, Burrows had a seriously inadequate unit, insufficiently officered and with many of the men almost untrained recruits.

- Burrows failed to take into account the effect of the conditions. The battle was fought on an exposed, dusty, dry plain in excessive heat. Many of the soldiers had nothing to eat that day and the supply of water failed early in the battle. The infiltration of the Afghan cavalry between the fighting line and the baggage prevented the supply of food, water and ammunition and the rescue of casualties. The crucial smooth bore guns were permitted to run out of ammunition and retire, fatally undermining the morale of the two companies of Jacob’s Rifles occupying an important position on the left of the infantry line.

- The experience of the 66th was dramatically expressed in Rudyard Kipling’s poem ‘That Day’ (see below). McGonagall also committed the battle to rhyme, perhaps less convincingly.

- The 66th were accompanied into battle by the dog Bobbie, owned by Sergeant Kelly. Bobbie survived the final stand of the Eleven and escaped to join the retreat, although wounded, making her way to Kandahar. On the regiment’s return to England, Bobby was presented by HM Queen Victoria at Osborne House with the Afghan War campaign medal, along with other survivors of the battle.

- E Battery, B Brigade, Royal Horse Artillery, earned 2 Victoria Crosses and 8 Distinguished Conduct Medals for its conduct during the battle and the retreat. The battery was formally thanked by the Viceroy on parade for its conduct.

- The Indian troops that fought all the successful battles of the Second Afghan War in the north of the country were from the Bengal Army. The Battle of Maiwand was the first major engagement of the war fought by the Bombay Army. The defeat, with the near annihilation of three infantry regiments, brought heavy criticism on the Bombay Army.

- The Battle of Maiwand caused a sensation in Britain and Europe. Two senior officers from Burrows’ force were tried by court martial, but acquitted. The battery commander of the smooth bore battery, Captain Slade of the Royal Horse Artillery, received the CB for his conduct in the battle.

- The conduct of individual British soldiers varied widely. The 66th ‘Berkshire Regiment’, known as the ‘Biscuit Boys’ after the Reading biscuit firm of Huntley and Palmer, was considered a steady mainstream infantry regiment. The regiment fought hard to repel the Afghans, several officers and soldiers dying defending the regiment’s colours. The Afghans were impressed by the courage of the men who fought it out in Khig and particularly by the determination of the Eleven who shot down numbers of their attackers and, when ammunition was exhausted, charged with the bayonet to their deaths. During the retreat, a number of British soldiers became incapably drunk, after raiding the officers’ stores and had to be left behind to be slaughtered by the pursuing Afghans. Sergeant Mullane of the Royal Horse Artillery received the Victoria Cross for charging recklessly in among the tribesmen overwhelming the guns and rescuing a wounded gunner. Gunner Cullen won the Victoria Cross for his conduct during the retreat.

- Sherlock Holmes’ amanuensis and friend, Dr John Watson, received the wound that caused him to leave India for 221B Baker Street while serving as surgeon with the 66th at the Battle of Maiwand.

- The fallen of the 66th, subsequently 2nd Battalion, the Royal Berkshire Regiment, are commemorated by a lion in Forbury Park, Reading, the county town of Berkshire; a dignified and sad memorial to Colonel Galbraith and his men, engraved around the base with the names of the soldiers of the 66th who fell at the Battle of Maiwand and elsewhere in Southern Afghanistan in the Second Afghan War.

- The lion should equally be considered a memorial to the soldiers of the Royal Horse Artillery, the 3rd Bombay Cavalry, the 3rd Scinde Horse, the 1st Grenadiers, the 30th Bombay NI, Jacob’s Rifles, and the Bombay Sappers and Miners who died in the service of the British Crown at the Battle of Maiwand.

- The closing paragraph of ‘My God-Maiwand‘ (see below) reads: “He (Brigadier-General Suleiman of the Afghan Army in 1970) laughed and added ‘In any case, the threat of an armed peasantry in Afghanistan is now so well appreciated abroad that not even the British will ever dare invade us again!’

- ‘Good Luck to you. It’s all up with the Bally Old Berkshires’ is what a soldier of the 66th called out to the departing E/B Battery as they galloped off, leaving the 66th to be annihilated by the on-coming Afghans; as recorded by Robert Baden-Powell in his book ‘Indian Memories’, after visiting the site of the Battle of Maiwand.

- Baden-Powell wrote that he made his visit to the battlefield with Sir Oliver St John who had fought at the Battle of Maiwand. St John escaped after the battle with his Afghan orderly, only to find that his collie was missing. The Afghan orderly returned to the battle and retrieved the dog.

- Another Baden–Powell anecdote of the battle was of the Roman Catholic chaplain of the 66th who carried a water skin around aiding the wounded. As one of the gun teams of E/B Battery escaped from the battle, they grabbed the chaplain and took him out with them.

- The 66th Regiment at the Battle of Maiwand is remembered in the ‘Bugle Pub’ in Central Reading.

Scene of the last stand of the 66th Regiment at the Battle of Maiwand on 27th July 1880 in the Second Afghan War: picture by Henry John Nuthall, Bengal Staff Corps 1880

That Day

(the poem Kipling wrote to commemorate the experience of the 66th Regiment at the Battle of Maiwand).

‘Last request’: Battle of Maiwand on 27th July 1880 in the Second Afghan War: picture by Harry Payne

It got beyond all orders an’ it got beyond all ‘ope;

It got to shammin’ wounded an’ retirin’ from the ‘alt.

‘Ole companies was lookin’ for the nearest road to slope;

It were just a bloomin’ knock-out — an’ our fault!

Now there ain’t no chorus ‘ere to give,

Nor there ain’t no band to play;

An’ I wish I was dead ‘fore I done what I did,

Or seen what I seed that day!

We was sick o’ bein’ punished, an’ we let ’em know it, too;

An’ a company-commander up an’ ‘it us with a sword,

An’ some one shouted “‘Ook it!” an’ it come to sove-ki-poo,

An’ we chucked our rifles from us — O my Gawd!

There was thirty dead an’ wounded on the ground we wouldn’t keep —

No, there wasn’t more than twenty when the front begun to go;

But, Christ! along the line o’ flight they cut us up like sheep,

An’ that was all we gained by doin’ so.

I ‘eard the knives be’ind me, but I dursn’t face my man,

Nor I don’t know where I went to, ’cause I didn’t ‘alt to see,

Till I ‘eard a beggar squealin’ out for quarter as ‘e ran,

An’ I thought I knew the voice an’ — it was me!

Survivors of the 66th at the Battle of Maiwand on 27th July 1880 in the Second Afghan War: picture by Harry Payne

We was ‘idin’ under bedsteads more than ‘arf a march away;

We was lyin’ up like rabbits all about the countryside;

An’ the major cursed ‘is Maker ’cause ‘e lived to see that day,

An’ the colonel broke ‘is sword acrost, an’ cried.

We was rotten ‘fore we started — we was never disciplined;

We made it out a favour if an order was obeyed;

Yes, every little drummer ‘ad ‘is rights an’ wrongs to mind,

So we had to pay for teachin’ — an’ we paid!

The papers ‘id it ‘andsome, but you know the Army knows;

We was put to groomin’ camels till the regiments withdrew,

An’ they gave us each a medal for subduin’ England’s foes,

An’ I ‘ope you like my song — because it’s true!

An’ there ain’t no chorus ‘ere to give,

Nor there ain’t no band to play;

But I wish I was dead ‘fore I done what I did,

Or seen what I seed that day!

Graves of soldiers of the 66th Regiment after the Battle of Maiwand on 27th July 1880 in the Second Afghan War

References for the Battle of Maiwand:

My God-Maiwand by Maxwell: an exhaustive authoritative account of the battle by a Gunner Officer.

The Road to Kabul; the Second Afghan War 1878 to 1881 by Brian Robson.

The Afghan Wars by Archibald Forbes

Recent British Battles by Grant.

The previous battle in the Second Afghan War is the Battle of Ahmed Khel

The next battle in the Second Afghan War is the Battle of Kandahar

To the Second Afghan War index