Robert the Bruce’s iconic victory of the Scots over the English fought on 23rd and 24th June 1314

The previous battle in the Scottish Wars of Independence is the Battle of Falkirk

The next battle in the Scottish Wars of Independence is the Battle of Dupplin Moor

To the Scottish War of Independence index

16. Podcast of the Battle of Bannockburn: Robert the Bruce’s iconic victory of the Scots over the English in 1314: John Mackenzie’s britishbattles.com podcast

Dates of the Battle of Bannockburn: 23rd and 24th June 1314.

Place of the Battle of Bannockburn: In Central Scotland, to the South of Stirling.

The Royal Arms of England at

the time of Edward II: Battle of Bannockburn 23rd June 1314: picture

by Mark Dennis,

Ormond Pursuivant

War: The Scottish War of Independence against the English Crown of Edward I and Edward II.

Contestants at the Battle of Bannockburn: A Scots army against an army of English, Scots and Welsh.

Commanders at the Battle of Bannockburn: Robert the Bruce, King of the Scots, against Edward II, King of England.

Size of the Armies at the Battle of Bannockburn: There is great controversy over every aspect of the Battle of Bannockburn due to the lack of contemporary accounts. The eminent Scottish historian William Mackenzie came to the conclusion that the English army comprised around 3,000 mounted men, knights and men-at-arms, and around 13,000 foot soldiers, including a detachment of Welsh archers. William Mackenzie put the Scots at around 7,000 men. Robert de Bruce’s army comprised foot soldiers with a force of around 600 light horsemen commanded by Sir Robert Keith, the Marischal.

Winner of the Battle of Bannockburn: The Scots trounced the English in the 2 day battle.

Uniforms and equipment at the Battle of Bannockburn:

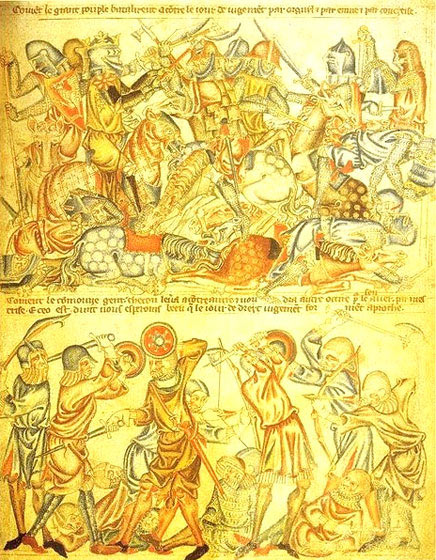

In order to re-conquer Scotland from Robert the Bruce King Edward II of England summoned his feudal army. The most important element in the feudal array was the mounted knighthood of Angevin England. A fully equipped knight wore chain mail, re-enforced by plate armour, and a steel helmet. He carried a shield, long lance, sword and, according to taste, axe or bludgeon and dagger. He rode a destrier or heavy horse strong enough to carry a fully equipped rider at speed. The heraldic devices of the knight were emblazoned on his shield and surcoat, a long cloth garment worn over the armour, and his horse’s trappings. An emblem might be worn on the helmet and a pennon at the point of the lance. Other knights on the field, including enemies, would be able to identify a knight from the heraldic devices he wore. Socially inferior soldiers such as men-at-arms would wear less armour and carry a shield, short lance, sword, axe, bludgeon and dagger. They rode lighter horses.

Knights of the period of the Battle of Bannockburn 23rd and 24th June 1314: picture by Edward Burne-Jones

Within each army units comprised men raised from particular areas or a nobleman’s household knights and men-at-arms. In the English army the King’s household provided a sizeable and homogenous fighting force.

The foot soldiers on each side fought with whatever weapons they had, which might be bows, spears, swords, daggers, bill hooks, bludgeons or any other implement capable of inflicting injury. They wore metal helmets and quilted garments if they could get them. Traditional feudal armies of the time considered battle to be an exercise between mounted knights. No account was taken of those further down the social scale and little sensible use made of them. For the English the battle was to be decided by the attack of their cavalry. The dismounted soldiers were present for other purposes, largely menial, in the eyes of the knighthood.

Because of the nature of the guerrilla war Robert de Bruce and the Scots had been fighting over the previous years against the English they had few mounted knights available for the battle. The Scots army comprised foot soldiers mostly armed with spears and that was the force Robert the Bruce had to rely upon.

While Bannockburn is held up as an important event for Scottish nationalism it is intriguing to remember that the knights on each side were essentially of the same stock, Norman-French or Northern European. The language spoken was in many instances still French.

As the Middle Ages progressed the limitations of mounted knights attempting to win battles alone were repeatedly revealed: the Battles of Charleroi, Crecy and Agincourt were three examples.

Bannockburn was again to show the inadequacy of largely unsupported heavy cavalry.

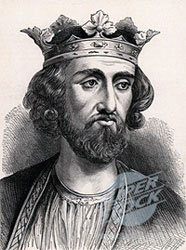

Edward I, King of England, Maleus Scotorum, and father of Edward II, 1239 to 1307: Battle of Bannockburn 23rd and 24th June 1314

The Background to the Battle of Bannockburn:

Edward I, King of England from 1239 to 1307 and father to King Edward II, conquered Scotland as he conquered Wales. Once the local forces had been overcome in open battle Edward’s system of occupation was to build a network of stone castles or walled towns each occupied by an armed force under a loyal local or English knight.

Edward I died on 6th July 1307 and his son Edward II became King of England. The King had to contend with a number of powerful noblemen each with large regional estates and substantial military resources. A similar politico-social system was in place in most areas of Western Europe. It took a king of considerable military and political acumen and ruthless resolve to keep the English nobility in order and to force them to pursue the national or royal interest as opposed to their own individual interests. Edward I was such a king while his son Edward II certainly was not. Edward II’s reign was blighted by simmering dispute, frequently breaking into outright warfare, between King and Nobles. A particular source of discord was Edward II’s reliance upon his favourite, Piers Gaveston, a Gascon knight, whom Edward made Earl of Cornwall. Gaveston was hated by most of the senior nobility of England, a group of whom finally assassinated him in 1312.

Robert de Bruce and his Scots followers rejoiced openly at the death of King Edward I. The Bruce now embarked on his war to push the English out of Scotland and to establish his dominance over his Scottish rivals as King of the Scots.

The English castles while a powerful mechanism for dominating occupied country with garrisons of small groups of armed knights and men had a major weakness which lay in its day to day security. During their campaign against the occupying English the Scots became masters of the art of taking fortifications by trick and surprise. A standard piece of kit for the Scots, the use of which they perfected, was the scaling ladder. There were rarely enough men in a castle to watch the length of the fortifications fully and inevitably there were periods when such watch as there was lapsed. Approaching with stealth the Scots would scale the walls and take the castle or town. The classic was the capture of Edinburgh Castle on 14th March 1313 by Randolph Earl of Moray. The castle watch actually looked over the wall at the point where the Scots were preparing to attack, before loudly moving on, leaving the Scots to scale the wall and open the gate to the waiting force, which then stormed the castle.

A particularly popular tale is the taking of Linlithgow Castle by William Bannock in September 1313. Bannock drove up in a cart filled with fodder for the garrison’s horses and stopped the cart in the gateway thereby preventing the garrison from closing the gate. Armed men leaped from beneath the fodder and, assisted by a band of men that rushed the gate, the castle was stormed.

As each castle or town was captured the fortifications built over many years by the English were destroyed so that the English could not re-establish their control of the country, even if the place was re-taken.

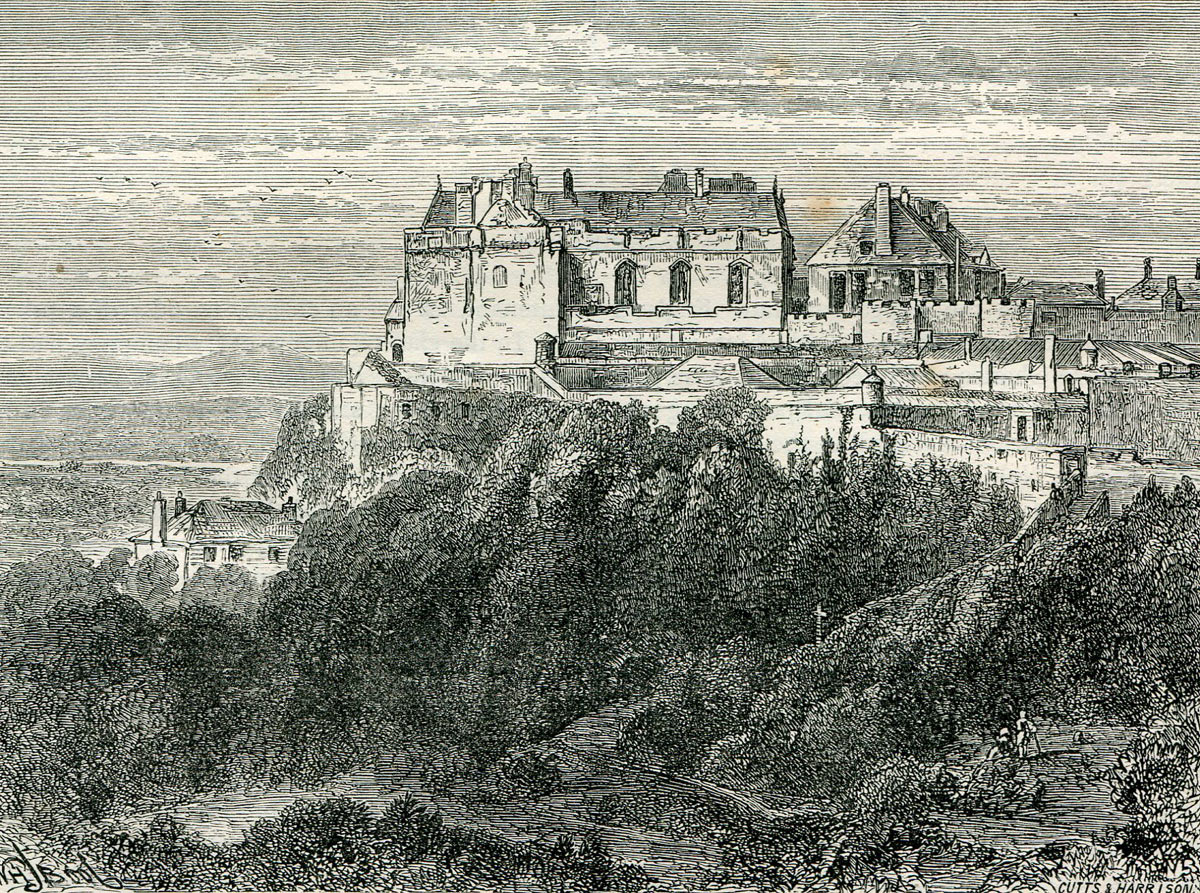

Finally few castles remained. One of these was Stirling Castle held for Edward II by Sir Philip de Mowbray. In around February 1313 the brother of King Robert de Bruce, Edward de Bruce, began a siege of Stirling Castle. In June 1313 de Mowbray put an offer to Edward de Bruce. The offer was that if Stirling Castle was not relieved by Midsummer’s Day 1314, 24th June, de Mowbray would surrender the castle to de Bruce. To comply with this requirement the relieving English army would need to be within 3 miles of the castle within 8 days of that date. De Bruce appears to have accepted this offer without thinking through the implications, or possibly without caring. His brother the king was, on the other hand, fully aware of the consequences of this rash agreement, which in effect compelled Edward II to launch a new invasion of Scotland.

At the end of 1313 Edward II issued the summonses for his army to assemble. The wording of these documents indicated that while the relief of Stirling Caste was the pretext, the intention was to re-conquer Scotland for the English Crown.

The shaky hold Edward II maintained over his nobility is illustrated by the number of powerful noblemen who refused to answer the call to arms: the Earl of Lancaster, the Earl of Warwick, the Earl of Warenne and the Earl of Arundel among others. The King’s call was answered by Henry de Bohun, Earl of Hereford and Constable of England, the Earl of Gloucester and the Earl of Pembroke. The Scottish Earl of Angus supported Edward.

Knights answering Edward’s summons were: Sir Ingram de Umfraville, Sir Marmaduke de Tweng, Sir Raoul de Monthemer, Sir John Comyn and Sir Giles d’Argentan, several of them Scottish. Other knights joined Edward’s army from France, Gascony, Germany, Flanders, Brittany, Aquitaine, Guelders, Bohemia, Holland, Zealand and Brabant. Foot soldiers came from all over England and archers from Wales.

Edward’s army assembled at Berwick in May 1314. There was complete confidence in victory over the Scots. The army began its advance into Scotland on 17th June 1314, the column covering a considerable area accompanied by numerous flocks of sheep and cattle to provide rations and carts carrying the baggage of the members of the army and the quantities of fodder required for the knight’s heavy fighting horses.

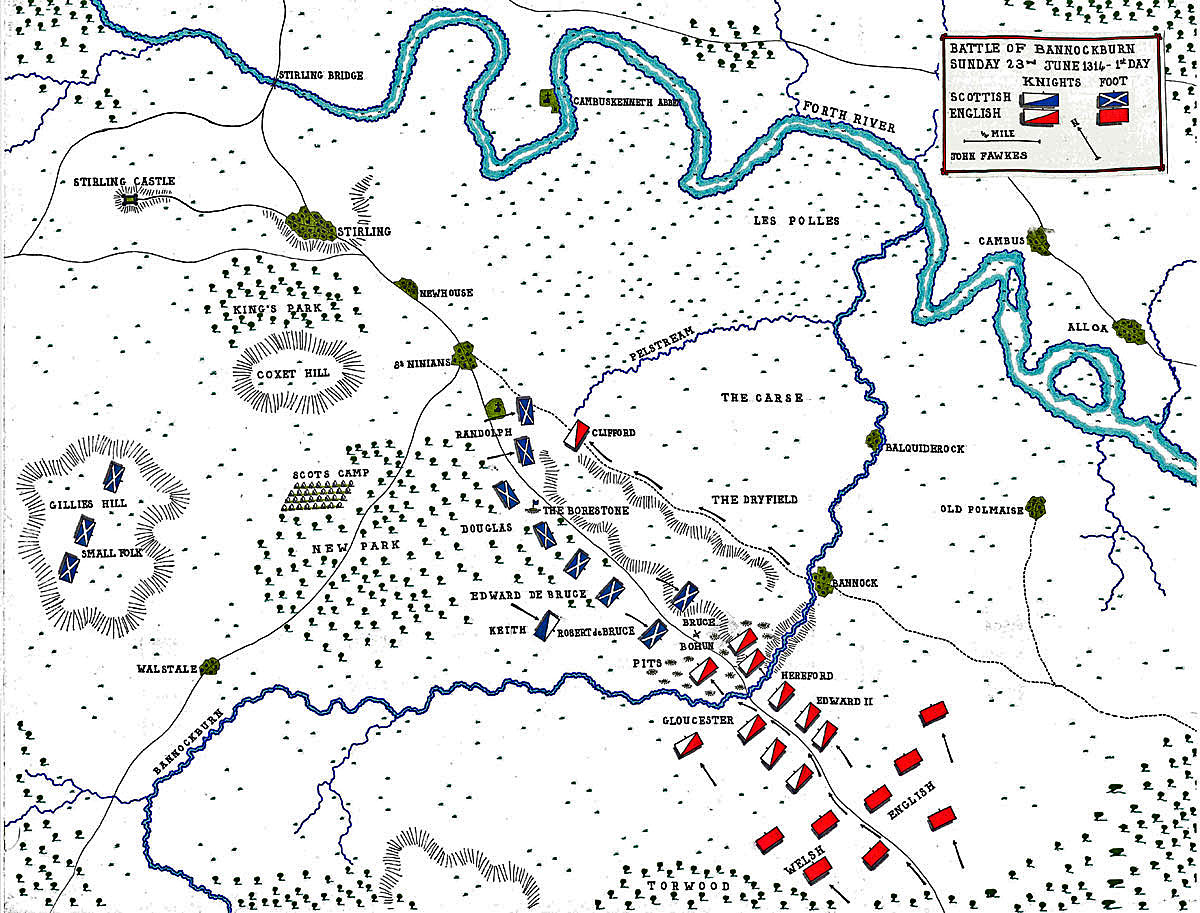

The army marched to Edinburgh and took the old Roman road to Stirling. Beyond Falkirk the road passed through the forest of Torwood, also known in French as Les Torres, before crossing the Bannockburn stream into the New Park and on to Stirling. To the right of the route wound the tidal waters of the River Forth. Along the river was the scrubland area known as Les Polles. The area to the north of the Bannockburn ford on the road route was known as the Dryfield of Balquiderock. A small tributary of the Bannockburn called the Pelstream Burn curled around to the West. Beyond the Pelstream a boggy area led down to the Forth.

Robert de Bruce assembled his army of Scottish foot soldiers to the South of Stirling and formed them into 4 battalions commanded by himself, Thomas Randolph Earl of Moray, James Douglas and his brother Edward de Bruce. These battalions were given the name of ‘Schiltrons’. The King’s schiltron comprised men from his own estates in Carrick and the Western Highlands. The other schiltrons men from the estates of their commanders and their associates. Randolph led men from Ross and the North: Edward de Bruce led men from Buchan, Mar, Angus and Galloway: Douglas men from the Borders. The small force of mounted knights and men-at-arms was commanded by Sir Robert Keith, Marischal to the King of Scotland.

Several of the Highland clans under their chiefs marched with the Scots army: William Earl of Sutherland, Macdonald Lord of the Isles, Sir Malcolm Drummond, Campbell of Lochow and Argyle, Grant of Grant, Sir Simon Fraser, Mackays, Macphersons, Camerons, Chisholms, Gordons, Sinclairs, Rosses, Mackintoshes, MacLeans, MacFarlanes, Macgregors and Mackenzies among them.

Some Scottish clans fought for Edward II: MacDougalls and MacNabs.

Robert the Bruce positioned his army in the New Park with Randolph’s schiltron to the fore and his own immediately behind it. The chosen method of combat was for each schiltron to form a bristling mass of spears which the English knights would be unable to penetrate. The Scots dug concealed pits across the front of their position and along the bank of the Bannockburn to break up any mounted charge against them.

Account of the Battle of Bannockburn:

The Scots soldiery was aroused at around day break on Sunday 23rd June 1314. Maurice the aged blind Abbot of Inchaffray celebrated mass for the army after which Robert de Bruce addressed his soldiers, informing them that anyone who did not have the stomach for a fight should leave. A great cry re-assured him that most were ready for the battle. The camp followers, known as the ‘Small Folk’, were sent off to wait at the rear of the field, probably on the hill called St Gillies’ Hill. The Schiltrons were formed for battle fronting the fords over the Bannockburn that the English must cross.

Edward’s army had marched some 20 miles on Saturday 22nd June 1314 arriving at Falkirk in the evening. Edward had left it late in leaving Berwick if he was to reach Stirling by Midsummer’s Day and it was necessary to make up lost time. Sir James Keith led a mounted to patrol to watch the arrival of the English Army and he found this a daunting sight as Edward’s men camped over a wide area, the sun glinting on a myriad of weapons and armour.

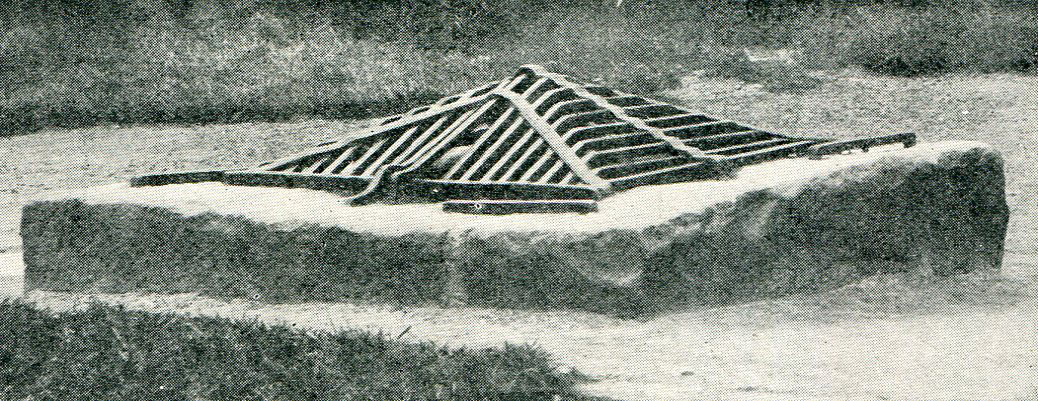

The bore-stone where Robert the Bruce’s standard was fixed: Battle of Bannockburn on 23rd and 24th June 1314

The English army was formed in 10 divisions; each led by a senior nobleman or experienced knight.

On Sunday 23rd June 1314 Edward’s army began its final march up to the Bannockburn. The King was met by Sir Philip de Mowbray who had ridden out of Stirling Castle with a body of horseman, taking the path through the boggy ground by the Forth leading to the Carse and across the Bannockburn.

De Mowbray tried to persuade Edward to abandon his advance to battle. De Mowbray seems to have had grave reservations as to the outcome, not shared by the headstrong nobles and knights that Edward led.

A body of some 300 horsemen under Sir Robert Clifford and Henry de Beaumont rode back to Stirling Castle with de Mowbray to re-enforce the garrison. This body took the path de Mowbray had ridden out on and passed under the noses of Randolph’s shiltron. Randolph received a stinging rebuke from his King, who remarked “See Randolph, there is a rose fallen from your chaplet. Thoughtless man. You have permitted the enemy to pass.”

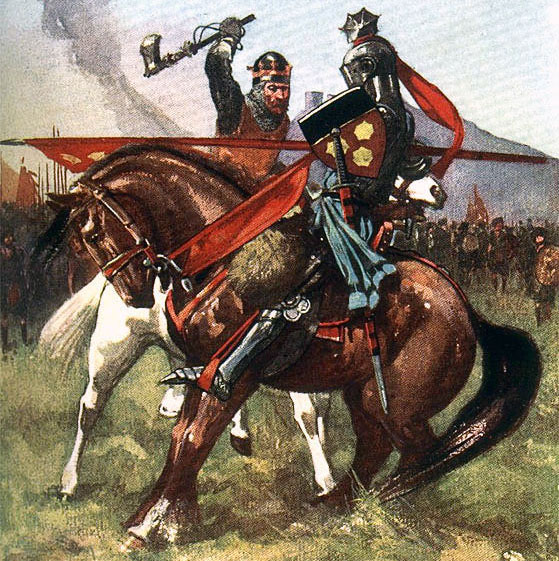

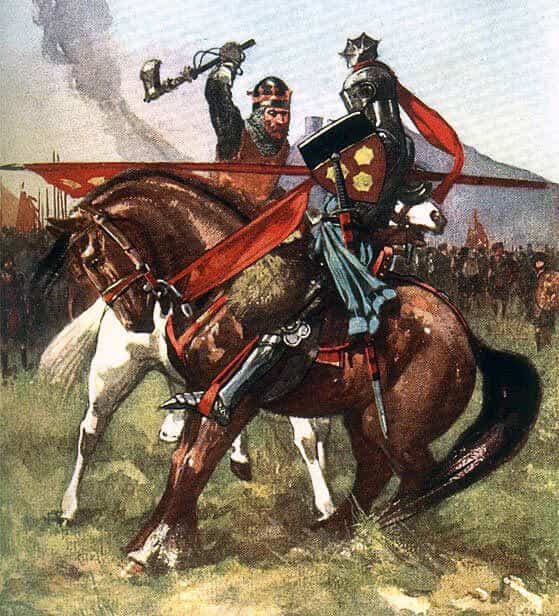

Robert de Bruce kills Sir Henry de Bohun in single combat on the first day of the Battle of Bannockburn on 23rd June 1314

Randolph rushed his foot soldiers down to the path to block the route of Clifford’s and de Beaumont’s force. A savage fight took place with the English horsemen unable to penetrate the spear points of Randolph’s hastily formed schiltron. The Scots were hard pressed and Douglas moved his men forward to give help but saw that the English were giving way. The English squadron broke in two with half riding for the castle and the remainder returning to the main army. In the initial attack Sir Thomas Grey was brought from his horse and taken, while Sir William D’Eyncourt was killed.

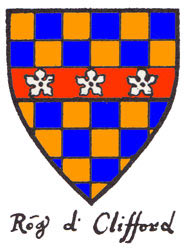

Shield of Sir Robert de Clifford,

knight in the English army: Battle of Bannockburn 23rd and 24th June 1314

While Clifford and de Beaumont were engaged with Randolph the main English Army moved out of the Torwood. The English advance continued inexorably with the advance guard under the Earls of Hereford and Gloucester riding to cross the Bannockburn and attack the Scots in the forest beyond. To the English it seemed inevitable that the Scots would withdraw and avoid battle in view of the enormous disparity in numbers and arms. It was at this point that Hereford’s nephew Sir Henry de Bohun galloped ahead of the advancing English array to challenge the Scots King to single combat.

Robert de Bruce rode forward to meet de Bohun. The contrast in their equipment was stark. De Bohun was fully armoured with lance and shield and rode a heavy destrier horse. De Bruce rode a light palfrey and was armed with sword and short axe. He was mounted to command infantry not to take part in a heavy cavalry charge. De Bohun rode at de Bruce with lance couched. De Bruce evaded de Bohun’s lance point and as the Anglo-Norman thundered past him struck him a deadly blow on the head with his axe. De Bohun fell dead.

Following their king’s triumph the Scots infantry rushed on the English army struggling to clear the Bannockburn, where the ford had compelled the mass of horsemen to pack into a narrow column. A terrible slaughter ensued, the English knights impeded by the shallow pits concealed with branches. Among the extensive English casualties the Earl of Gloucester was wounded and unhorsed, being rescued from death or capture by his retainers.

Robert de Bruce strikes and kills Sir Henry de Bohun with his axe in single combat before the Battle of Bannockburn on 23rd June 1314: picture by John Hassall

After the engagement such of the English as had come through the ford re-crossed the Bannockburn and the Scots infantry returned to their positions in the forests of the New Park. The English army had been convincingly repelled. Robert de Bruce’s immediate lieutenants reproached him for the risk he had taken in giving de Bohun single combat and the King simply regretted his broken axe.

With the end of the day Robert de Bruce consulted with his commanders as to the future conduct of the battle. The King proposed that the Scots army might withdraw from the field, leaving the English army to attempt a re-conquest of Scotland until a lack of supplies forced it to withdraw south of the border. On the other hand the Scots could renew the battle the next day. Bruce’s commanders urged a resumption of the battle. Soon afterwards a Scottish knight, Sir Alexander Seton, arrived from the English camp, having decided to resume his fealty to the Scottish King, and advised de Bruce that morale was low in the English army. Seton said “Sir, if you wish to take all of Scotland, now is the time. Edward’s army is grievously discouraged. You may beat them on the morrow with little loss and great glory.”

In the English camp on the far side of the Bannockburn the infantry was more than discouraged. The word was that the war was unrighteous and this had been the cause of the day’s defeat. God was against the English army. Order broke down and the horde of foot soldiers ransacked the supply wagons and drank through the night. Heralds declared the victory was certain in the morning but few were convinced.

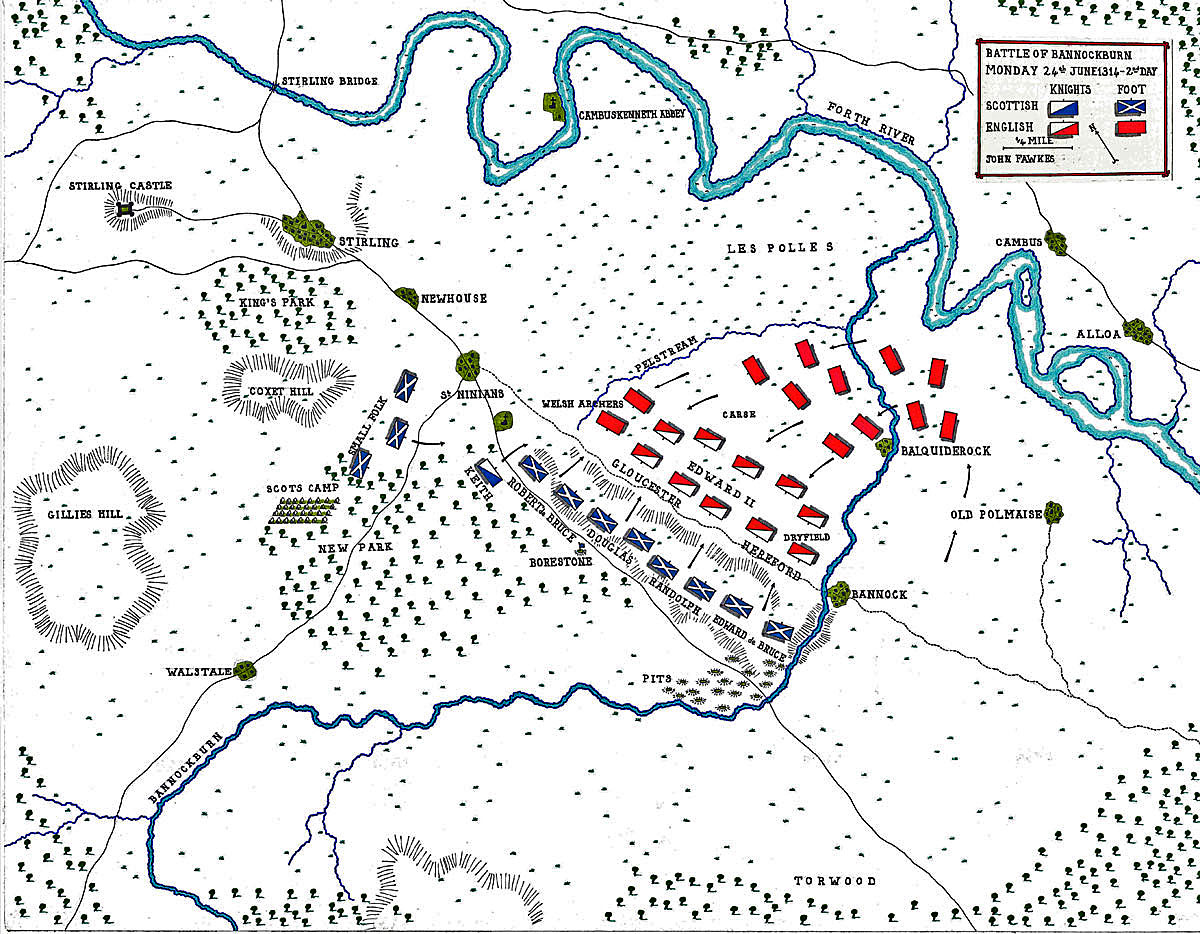

It was decided that the assault in the morning should be brought about by crossing the Bannockburn nearer to the River Forth to avoid the area of pits. The English knights would then deploy and charge the Scots positioned in the New Park.

Early in the morning the English crossed the Bannockburn and formed up along the edge of the Carse of Balquiderock, ready to charge the Scots. It was not a good position. The left of the English line lay on the Bannockburn, the right was hemmed in by the Pelstream. There were too many English for the narrow area.

The Abbott of Inchaffray again passed among the Scots soldiery, blessing them. Again he held mass. The Abbott had brought relics of St Fillan and Abbott Bernard of Arbroath had brought the reliquary casket of St Columba to encourage the simple and superstitious soldiery. Seeing the kneeling Scots Edward commented to de Umfraville that they were craving his forgiveness for opposing him. De Umfraville answered that they were craving divine forgiveness.

Shield of Sir Pain de Tiptoft knight in the English army: Battle of Bannockburn 23rd and 24th June 1314

As part of the morning’s ceremony de Bruce knighted those of his army he considered had distinguished themselves on the previous day including Walter Stewart and James Douglas.

The Scots army then began to advance to the astonishment of the English that foot soldiers should advance against mounted knights.

Shield of Sir Edmund de Mauley,

knight in the English army: Battle of Bannockburn 23rd and 24th June 1314

Edward said to de Umfraville “Will these Scotsmen fight?” de Umfraville said “These men will gain all or die in the trying.” Edward said “So be it” and signalled for the trumpets to sound the charge.

First off the mark was the Earl of Gloucester. Edward had treated his suggestion of a day to recover from the previous day’s battle as cowardice and Gloucester intended to disprove this slur. The English knights hurled themselves onto the Scottish spear line with a terrible crash. The charge fell on Edward de Bruce’s schiltron. Many of the English knights were killed in the impact: Gloucester, Sir Edmund de Mauley, Sir John Comyn, Sir Pain de Tiptoft, Sir Robert de Clifford among them.

Robert de Bruce strikes and kills Sir Henry de Bohun with his axe in single combat before the Battle of Bannockburn on 23rd June 1314: picture by Ambrose de Walton

Randolph’s and Douglas’s schiltrons came up on the left flank and attacked the unengaged English cavalry waiting to charge in support of the first line.

On the extreme English right flank the Welsh archers came into action causing a pause in the Scots attack until they were dispersed by Keith’s force of light horsemen.

Supporting the assault of the spearmen of the schiltrons the Scots archers poured volleys of arrows into the struggling English cavalry line as it was pushed back across the dry ground into the broken area of the Carse.

The Scots spearmen pressed forward against the increasingly exhausted and hemmed in English army. The cry went up “On them. On them. They fail. They fail.”

The final blow was the appearance of the ‘Small Folk’, the Scots camp followers, shouting and waving sheets. The English army began to fall back to the Bannockburn with ever increasing speed and confusion and foot soldiers and horsemen attempted to force their way across the stream. High banks impeded the crossing and many are said to have drowned in the confusion. Many escaped across into the area of tidal bog land known as Les Polles where they fell prey to their exhaustion, heavy equipment and the knives of the Small Folk.

Aftermath to the Battle of Bannockburn:

Once it was clear that the day was lost, the Earl of Pembroke seized King Edward’s bridle and led him away from the battle field surrounded by the Royal retainers and accompanied by Sir Giles de Argentan. Once the King was safe de Argentan returned to the battle and was killed.

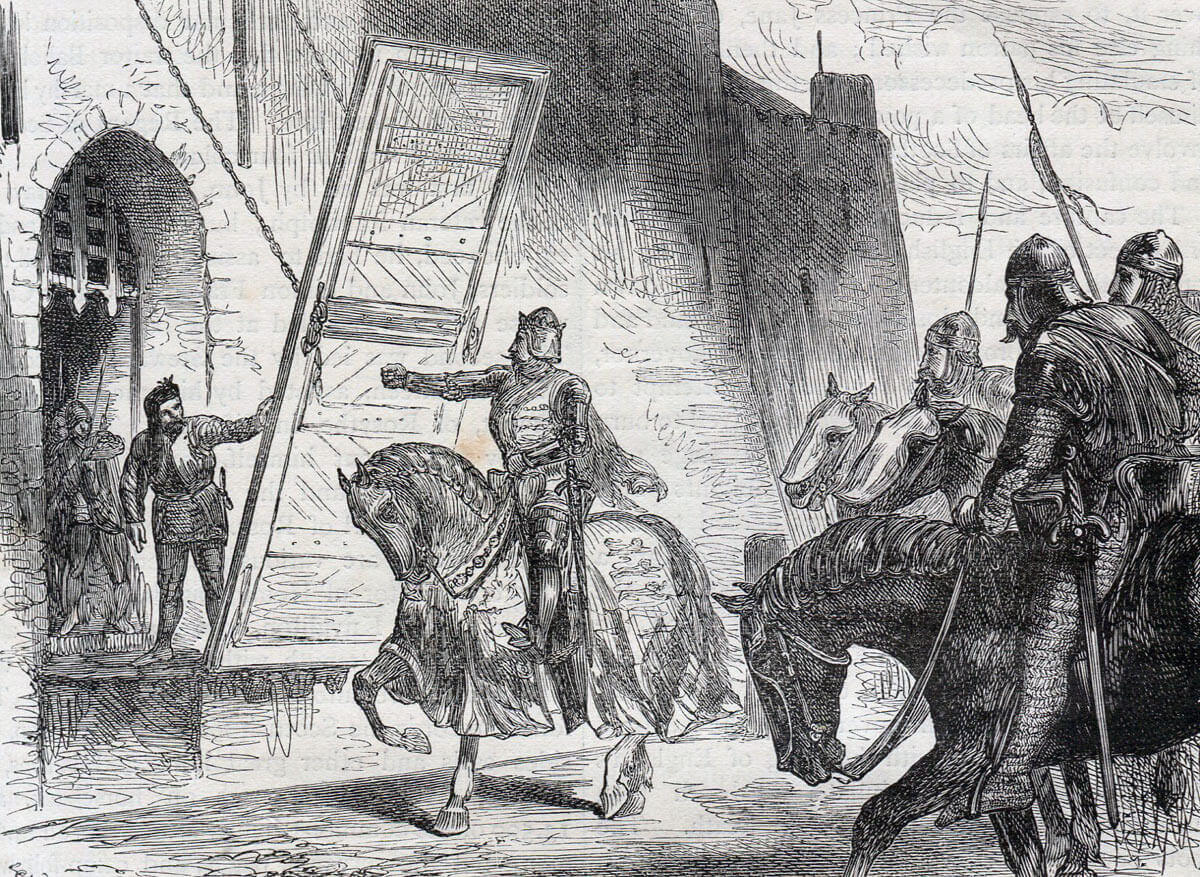

King Edward II of England refused entry to Stirling Castle after the battle by Sir Philip de Mowbray, the governor: Battle of Bannockburn 23rd and 24th June 1314

Shield of Sir Raoul de

Monthemere, knight in the English army:

Battle of Bannockburn 23rd and 24th June 1314

Edward was taken to the gates of Stirling Castle. Here de Mowbray urged the King not to take refuge in the castle as he would inevitably be taken prisoner when the castle was forced to surrender to the Scots. Edward took this advice and with his retinue skirted around the battlefield and rode for Linlithgow. He then rode to Dunbar and took boat to Berwick.

The memorial to Sir Edmund de Mauley in York Minster: Sir Edmund died fighting in the English army: Battle of Bannockburn 23rd and 24th June 1314

A group of nobles, the Earl of Hereford, Robert de Umfraville Earl of Angus, Sir Ingram de Umfraville and others fled to Bothwell Castle where they were taken and handed to the Scots by the Castle Constable Sir Walter FitzGilbert.

The Earl of Pembroke led his Welsh archers away from the battle field and after a tortuous and hazardous march brought them back to Wales. One of these archers may have been the source for the account of the battle in the Valle Crucis Abbey chronicle.

Coat of Arms of Sir Marmaduke de Tweng of the English Army captured at the battle by the Scots: Battle of Bannockburn 23rd and 24th June 1314

Others among the prisoners were Sir Marmaduke de Tweng and Sir Raoul de Monthemere.

King Robert de Bruce returned the bodies of Gloucester and Sir Robert de Clifford to Berwick for burial by their families. De Bruce conducted a vigil over the body of Gloucester to whom he was related.

Casualties at the Battle of Bannockburn:

There is little reliable evidence on the number slain. The English probably lost around 300 to 700 mounted knights and men-at-arms killed in the battle with many more killed in the flight from the field.

Few foot soldiers are likely to have been killed in the battle. It is unknown how many Scots were killed.

Memorial in Copthorne Church of Sir Edmund de Twenge who fought with the English army: Battle of Bannockburn 23rd and 24th June 1314

The war against the English continued with years of Scots invasions of England and some counter invasions. Berwick changed hands several times. The Pope, acting on the English account, excommunicated King Robert de Bruce and a number of prominent Scots clergy and placed Scotland under interdict. In 1320 the Declaration of Arbroath was signed in Arbroath Abbey under the seals of 8 Scottish Earls and sent to the Pope. It contained a statement of the origins of the Scottish people and a declaration of their independence from England.

Heraldic representation of Robert the Bruce, King of Scotland: Battle of Bannockburn 23rd and 24th June 1314

© The Heraldry Society of Scotland 2004

The statue of Robert de Bruce on the battlefield: Battle of Bannockburn 23rd and 24th June 1314 by Pilkington Jackson

In 1327 Edward II was deposed by his nobles and senior clergy. His son Edward III became the new king. Edward II died in Berkeley Castle on 21st September 1327 under suspicion that he had been murdered.

The Treaty of Edinburgh bringing the long wars between England and Scotland to an end was signed on 17th March 1328 and ratified by Edward III on 4th May 1328.

King Robert de Bruce died at Cardross on 7th June 1329.

Anecdotes from the Battle of Bannockburn:

- Before the Battle of Bannockburn Friar Baston of King Edward II’s entourage wrote a ballad celebrating the coming victory over the Scots. Baston was captured and required to re-write his ballad to record the true victors. He did so and it remains a valuable record. He was then released by Robert de Bruce.

- The Earl of Hereford was exchanged for King Robert’s wife and daughter who had been held for a number of years by the English, Queen Mary in a cage on the wall of Roxburgh Castle, and some 12 other Scots prisoners held by Edward.

- During the night of the First Day of the Battle of Bannockburn the Earl of Athol, a Scots nobleman who supported Edward II, raided the Scottish baggage train at Cambuskenneth Abbey on the North East bank of the Forth, killing the guard under Sir William de Erth of Airth and ransacking the baggage. After the battle Athol was forced to flee to England where he died.

- The Scottish song ‘Scots wa hae’ commemorates the Battle of Bannockburn.

- In August 1320 a plot against King Robert de Bruce’s life was discovered among a group of Scottish knights. Sir David de Brechin, a knight of considerable repute for his conduct in the Crusades, was found to have knowledge of the plot and was hung, drawn and quartered in Perth. Sir David had fought for the English at the Battle of Bannockburn before giving his allegiance to King Robert.

References for the Battle of Bannockburn

Battle of Bannockburn by William Mackenzie

British Battles by Grant.

Battles in Britain 1066-1547 by William Seymour.

The Art of War in the Middle Ages Volume Two by Sir Charles Oman

The previous battle in the Scottish Wars of Independence is the Battle of Falkirk

The next battle in the Scottish Wars of Independence is the Battle of Dupplin Moor

To the Scottish War of Independence index

16. Podcast of the Battle of Bannockburn: Robert the Bruce’s iconic victory of the Scots over the English in 1314: John Mackenzie’s britishbattles.com podcast