The account of General Braddock’s expedition to Fort Duquesne in 1755:

Part 6: Braddock’s march to Will’s Creek, via Alexandria, Frederick and Winchester

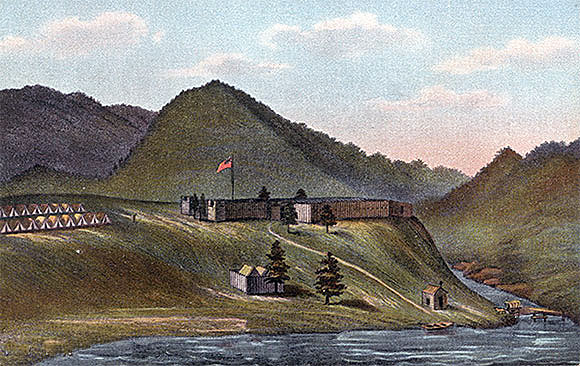

Fort Cumberland in 1755 (mistakenly given a USA Flag): the Potomac is in the foreground with Will’s Creek on the right: Death of General Edward Braddock on the Monongahela River on 9th July 1755 in the French and Indian War

The previous section on Braddock’s defeat on the Monongahela in 1755 is Part 5: Braddock’s regiments, Halkett’s 44th and Dunbar’s 48th, and his departure for Virginia.

The next section on Braddock’s defeat on the Monongahela in 1755 is Part 7: Braddock’s army at Fort Cumberland in Maryland in May 1755.

To the French and Indian War index

The arrival of General Braddock’s deputy quartermaster general in Virginia:

The deputy quartermaster general for Braddock’s force, Sir John Saint Clair, sailed in His Majesty’s Ship Gloucester in early November 1754 with Ellison and Mercer, appointed lieutenant-colonels in Shirley’s and Peperrel’s, the new regiments to be raised in the northern colonies of America. Saint Clair left before General Braddock reached England from France on 17th November 1754 in answer to the Duke of Cumberland’s summons to receive his appointment as commander-in-chief in America, so there was no opportunity for Braddock and Saint Clair to confer before leaving Britain.

Sir John Saint Clair arrived at Hampton in Virginia on 9th January 1755 and immediately travelled to Williamsburg, the Virginia capital, to meet the Deputy Governor of Virginia Robert Dinwiddie and begin his work.

Saint Clair arrived well in advance of the main force, with instructions to carry out several preparatory tasks. These included establishing a hospital at Hampton, overseeing the recruitment of men for the two regiments from Ireland Halkett’s 44th and Dunbar’s 48th and the new Virginia companies, speeding up the assembly of wagons and horses for the movement of baggage and supplies, ensuring that supplies were gathered for the troops for the march to Fort Duquesne, checking that suitable buildings were available at Will’s Creek to establish a forward base for the force and ensuring that the upper section of the Potomac was navigable to enable the troops, artillery and baggage to be transported up the river to Will’s Creek.

Sir John’s first task was to acquire a building at the port of Hampton for a military hospital, in anticipation of significant numbers of sick among the soldiers, following the voyage from Britain. There was no building sufficiently large for this purpose, forcing Saint Clair to make a board and lodging arrangement throughout the town. In the event, there appear to have been no soldiers requiring hospital treatment from the voyage, or so it was claimed by Braddock. One soldier was lost overboard.

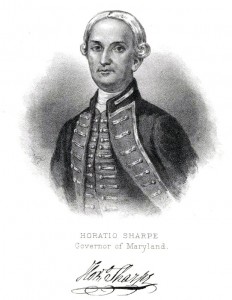

Dinwiddie’s agents were recruiting men for Braddock’s regiments and the Virginia companies across the colony, collecting them at Fredericksburg, Winchester and other centres of population. Horatio Sharpe, Lieutenant Governor of Maryland, similarly organised recruiting in his colony.

An early recommendation made by Saint Clair was that the regiments from Ireland be retained on board ship and taken straight up the Potomac River to Alexandria, to be there disembarked. Causing the army to march across country from Hampton to Alexandria would take some three weeks longer, Saint Clair estimated after consulting with Dinwiddie. Saint Clair seems to have changed his mind and proposed putting the men into camp to recover from the voyage and conduct training. Braddock rejected this proposal as wasting too much time and adopted Saint Clair’s original scheme of disembarking the army at Alexandria. It had been the expectation of the Duke of Cumberland that the troops could be taken by ship much if not all of the way up the Potomac River to Wills’ Creek.

During the preparations for the campaign Dinwiddie and the Virginia authorities made several assurances to Saint Clair and Braddock; that a sufficient number of wagons and horses (150 wagons with 4 horses each) would be forthcoming from Virginia as transport for Braddock’s army; that sufficient supplies would be provided in Virginia; that the roads in Virginia were adequate to accommodate the force and its transport; that the distance from Will’s Creek to Fort Duquesne was around 15 miles; and that there was a road from Will’s Creek to Fort Duquesne.

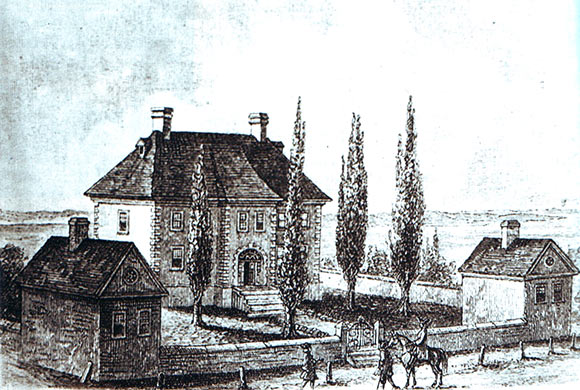

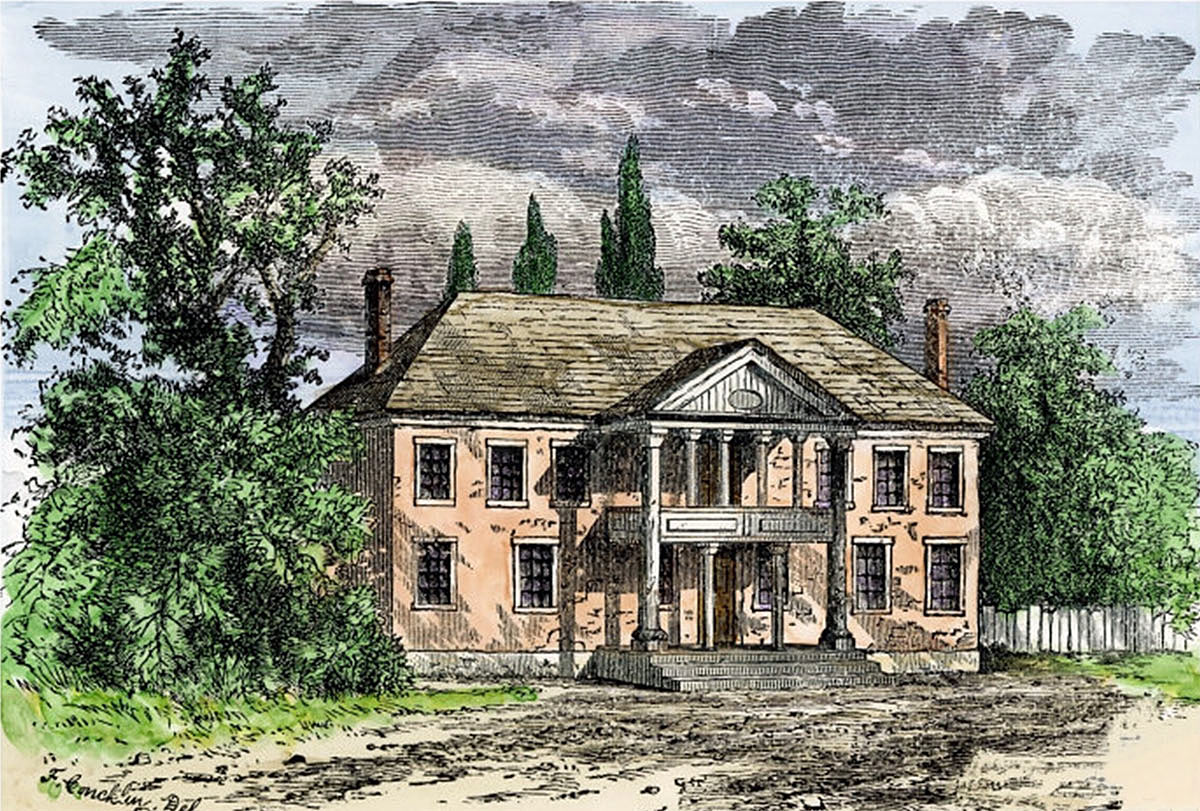

Governor’s Mansion at Williamsburg: Death of General Edward Braddock on the Monongahela River on 9th July 1755 in the French and Indian War

With respect to every one of these assertions Dinwiddie and the Virginia authorities either knew or suspected that they were untrue or had no reason to believe that they were true. The Virginia authorities misled the British government for their own purposes and gain; their aim being to ensure that Braddock’s army marched to Will’s Creek through Virginia and constructed a road from Virginia to the grant of land to the Ohio Company at the Ohio Forks.

On 16th January 1755 Saint Clair set out for Will’s Creek, the forward base for the march to Fort DuQuesne situated at the north-western tip of Virginia on the most northern bend of the Potomac River. The duties Saint Clair undertook on his journey were; to inspect the recruits for the regiments from Ireland and the Virginia companies assembled at the various places on his way to Will’s Creek; to ensure that the fort at Will’s Creek was in suitable order for the arrival of the army and to inspect the Potomac River route to Will’s Creek.

On 18th January 1755 Saint Clair reached Fredericksburg and on 22nd January 1755 he arrived at Winchester, where he stayed with Lord Fairfax before travelling on to Will’s Creek, arriving there on 26th January 1755. Saint Clair reported his findings in letters to Braddock which awaited the general’s arrival at Hampton.

Saint Clair was unimpressed by the roads in north-west Virginia, which he described as being the worst roads he had encountered (Saint Clair seems to have travelled extensively across Europe). He complained that in many places the road simply followed the course of a stream, the traveller constantly wading in water.

Saint Clair was critical of the selection of Will’s Creek as a base. He described the fort as simply an area of ground surrounded by a fence.

Saint Clair was emphatic that the place from which to begin the march to Fort Duquesne was not Will’s Creek, but a point a few miles further up the Main Branch of the Potomac at the confluence with the Savage River.

After attempting to travel by boat down the Potomac from Will’s Creek to Alexandria, Saint Clair stated that it was not feasible to use the river for transportation from Alexandria upstream to Will’s Creek due to the rapids and extensive reaches of shallow water.

In most of the other areas, in spite of his efforts, Saint Clair was almost completely unsuccessful. No horses, wagons or supplies were available for the march to Will’s Creek and Fort Duquesne. A constant theme in Saint Clair’s letters, subsequently taken up by Braddock in his reported to London, was the ignorance of the Virginians of their own colony and its resources and particularly of the remote area in the north-west.

Governor Horatio Sharpe of Maryland was in Fredericksburg, Virginia, on 26th January 1754, reviewing the recruits enlisted for Braddock’s force. Sharpe then travelled to Williamsburg to see Robert Dinwiddie, checking the progress in recruiting as he travelled, before returning to Maryland on 13th February 1754 via Fredericksburg. Sharpe reported being unimpressed by the recruits and discharged a number as unsuitable for service. Sharpe found one recruit to be missing a leg.

Although Sharpe had only been in America since August 1753, he was to provide Braddock with useful advice in preparing his army and on how to conduct the advance through the wilderness to the Ohio Forks. Braddock largely ignored this advice.

Saint Clair was impressed by a body of 80 recruits raised by Sharpe in Maryland which he allocated to the 44th and 48th regiments.

The threat posed by the French colony of New France (French Canada) to the British colonies in America:

The population of New France appears in 1755 to have been around 60,000. This compared with the population of the British colonies of 1,170,760, of whom 236,420 were black slaves. The population of Pennsylvania was 119,666 and of Virginia 231,033, of whom 101,000 were black slaves. Nine of the British colonies in North America each had, in 1755, populations the same or greater than that of New France.

The source of recruits for Braddock’s force:

It is one of the most persistent claims in relation to the Braddock expedition that the final battle showed the difference in fighting methods between British and Americans. For this claim to have validity it must be possible to distinguish between the two nationalities in Braddock’s force.

Recruitment in America for Braddock’s force in 1754 and 1755 was into a general pool, from which the best material was enlisted into the two regiments from Ireland, the 44th and the 48th, with the balance formed into the Virginia companies of Rangers and Carpenters. Once the 44th and 48th regiments were in America, each conducted recruiting drives on its own account, keeping the men enlisted.

The soldiers recruited in America would seem to have been mainly recent immigrants from England, Scotland and Ireland. Many were indentured servants from Britain, Ireland and Europe, who used the recruitment route to escape their bondage.

While there was a Virginian population of long standing in the colony, it seems that few took part in Braddock’s expedition. Of those that did serve many did so as officers, one being George Washington.

Even then many of the officers in the Virginia companies were recent immigrants, mostly from England and Scotland.

Needing more subalterns for the 44th and 48th Regiments, Braddock commissioned a number of new officers from long-standing Virginian and Maryland families. There were probably as many ‘American’ officers in the 44th and 48th as in the Virginia companies.

There was a small residue of soldiers from the Virginia Regiment of 1754 still at Will’s Creek, following Washington’s Fort Necessity debacle in July 1754. Many of these soldiers were recent immigrants from England, Scotland and Ireland. It would appear that the remnants of the Virginia Regiment were left at Will’s Creek as a garrison for Fort Cumberland, when Braddock marched to the Monongahela, and took no part in the final battle.

The tendency to see a distinction between the performance of British and American troops is further encouraged by the practice of some authorities of referring to units other than the 44th, the 48th, the artillery and the seamen as ‘American’. In fact the three independent companies from New York and South Carolina were regular British troops, if elderly and retired.

Probably the nearest to a genuinely American unit was the company brought by Captain Bryce Dobbs from North Carolina. This company was under Dunbar’s command and not present at the battle.

The expectations of the British:

Pargellis and other informed commentators on the French and Indian War state that not until British generals began fully to understand the problems of warfare in North America; the distances, the virgin forests, the apparently quixotic behaviour of the native inhabitants, the make-up and racial origins and political leanings of the various sections of the colonial population, the intransigence of many of the colonists, the waterways and the problems of supply, did progress in the war become possible.

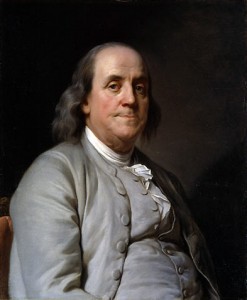

Braddock was the first of these generals. His successors had the reports of their predecessors to act on, if they chose. Braddock went to America with the plan for his first campaigning season imposed upon him by the Duke of Cumberland; being to march to the Ohio and take Fort Duquesne, then march up the Allegheny to take the French forts at River Le Boeuf before moving on to Fort Niagara. In conversation with Benjamin Franklin, as described in Franklin’s autobiography, Franklin recorded that Braddock said “After taking Fort Duquesne I am to proceed to Niagara and having taken that, to Frontenac, if the Season will allow time; and I suppose it will; for Duquesne can hardly detain me above three or four days; and then I see nothing that can obstruct my March to Niagara.”

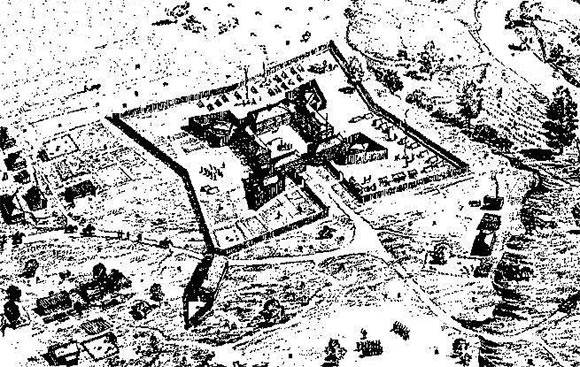

Fort Le Boeuf, one of the three French forts between Lake Erie and the Le Boeuf River (later known as Frenchman’s Creek)

In fact the march from Frederick, where Braddock made this assertion, to the Ohio Forks took Braddock’s force just over two months, not three or four days. In addition to underestimating completely the distances involved and the immense difficulty of moving bodies of troops equipped with guns and supplies across inland America, Cumberland, Braddock and the other British officers failed to grasp the nature of the wilderness to which they were committing their troops. As has been repeatedly stated, they were not assisted by the wilful misrepresentations of the Virginia authorities.

On 12th May 1755 at Fort Cumberland (Will’s Creek), Braddock issued an order stating that any soldier who prevented a local from bringing produce to the market at the fort would suffer death. This was a revealing order. In European warfare, an army on the march would encamp at the end of a day’s journey and the local inhabitants would bring their produce to a market in the camp for sale to the officers and soldiers, who were responsible for feeding themselves. Braddock ordered a market to be set up at Fort Cumberland, but no locals came in with their produce. Braddock’s assumption must have been that soldiers were intercepting the locals and buying or stealing their produce. Braddock had not grasped that he and his army were in the middle of a wilderness and that there were no locals. The threat of a death sentence shows the degree of concern that the lack of supplies was causing Braddock and his senior officers.

Transport and Supply:

The only vehicles Braddock’s force brought with them from England were the few carts especially adapted for transporting ammunition and the expedition’s cash. Transport for the soldiers’ equipment and supplies of food were to be obtained in Virginia through the offices of Dinwiddie, the Deputy Governor of Virginia. Dinwiddie was also directed by the Home Government to stockpile the supplies of food the force would need.

Dinwiddie complied with neither of these requirements. He did not have the finance and it would seem that Virginia did not have the stocks of agricultural wagons usually available in a European theatre of war or, as a tobacco economy, the foodstuffs required by the troops. Virginia imported its staple foods from the Northern Colonies and the West Indies.

The practice in Europe was that wagons supplied to armies came with the driver. It may be that with the slave economy in Virginia, plantation owners were not prepared to allow their drivers to leave the area of their estates for fear they would abscond.

Braddock was rescued by the intervention of Benjamin Franklin, who hired the wagons required and obtained supplies in Pennsylvania. A delay of around three weeks in beginning the march to Fort Duquesne was thereby incurred.

Transport continued to be a significant problem and the troops at no time had sufficient supplies of food. A large quantity of flour was destroyed by rain. By the end of the march to the Ohio Forks in early July 1755, Braddock’s troops were under-nourished and suffering from the onset of scurvy and other ailments arising from an inadequate diet. Never a competent military force, the efficiency of Braddock’s troops was further significantly undermined.

In spite of the colony’s failure to supply the transport and foodstuffs required for Braddock’s force, the Virginians complained when Dunbar’s 48th Regiment took a route to Will’s Creek via Frederick in Maryland. As Braddock pointed out in one of his furious letters to Napier in London, he had little choice but to march through Maryland, as the carters from that colony with the small number of wagons available refused to cross into Virginia.

The rapids on the Potomac River above Rock Creek, unnavigable to the sort of boats available to Braddock

Braddock’s arrival in Virginia:

Braddock’s ship arrived from England at Hampton, Virginia, on 23rd February 1755. The fleet with the rest of Braddock’s force arrived at Hampton in the period up to 11th March 1755.

On arrival, Braddock went straight to Williamsburg to confer with Dinwiddie and Saint Clair. Saint Clair recommended that the troops disembark and go into encampments at various locations across Virginia, to recover from the journey and establish their training and discipline. Braddock was not having any delay or splitting up of the force. Braddock directed that the soldiers remain on board the transports and be taken immediately up the Potomac to Alexandria, the highest point on the river to which seagoing ships had access, as Saint Clair and Sharpe had established during their reconnaissance to Will’s Creek.

The transports arrived at Alexandria on around Sunday 23rd March 1755. The soldiers had been on board ship for three months.

Other Ohio Company Personnel immediately involved in Braddock’s campaign:

Thomas Cresap, living on the north bank of the Potomac River within 7 miles of Will’s Creek, was appointed an agent for Braddock’s Army by Dinwiddie. Cresap was one of the founding members of the Ohio Company, although not a Virginia gentleman. His failure to perform his duties was one of the reasons for the delay at Fort Cumberland and the inadequacies of Braddock’s Army’s supply.

Christopher Gist, who had conducted several explorations of the Ohio country for the Ohio Company, was, on Dinwiddie’s recommendation, appointed Braddock’s personnel guide. This made sense in that Gist was fully conversant with the route to be taken through the area where he had for a period lived (Gist’s Plantation) and which he had surveyed.

Gist’s son Richard was sent to recruit Cherokee Indians from North Carolina for Braddock’s Army. He returned without any recruits.

George Croghan, another erstwhile employee of the Ohio Company, was given the task of raising a force of Indians for Braddock’s Army.

Alexandria:

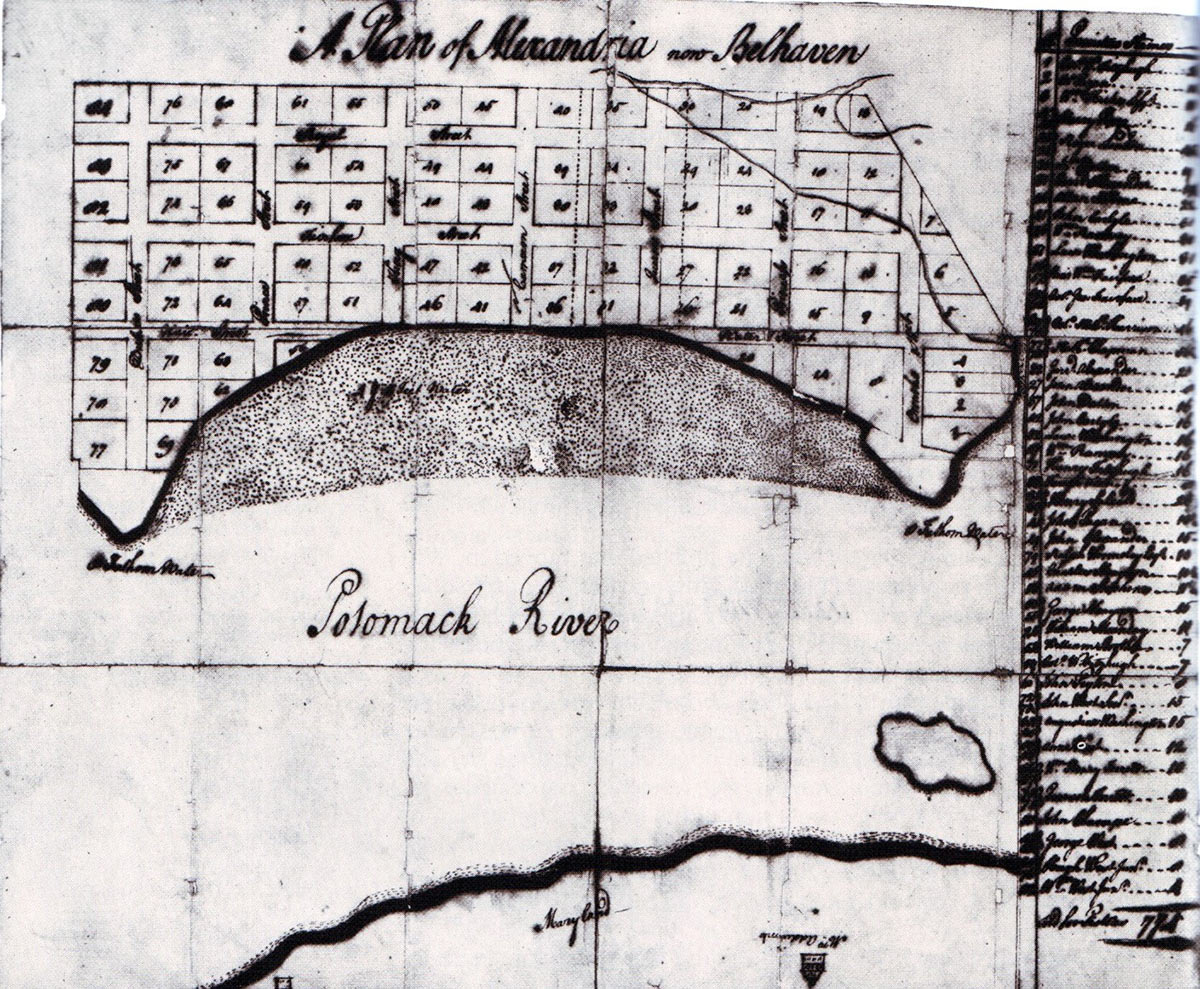

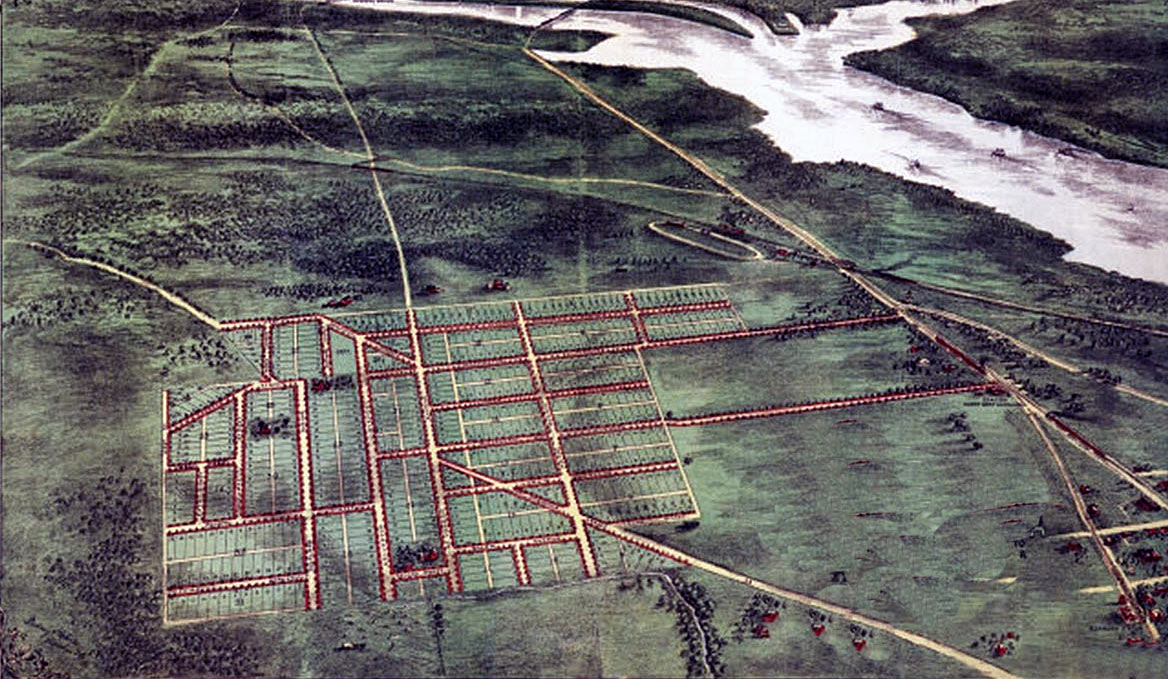

Alexandria was founded in 1753 on the southern bank of the Potomac in Virginia. It comprised a criss-cross of streets with houses to be built or being built on the plots between the streets. Few were complete and the town was far from finished. The troops went ashore and established a camp to the west of the town. Alexandria would be the base for Braddock’s force until it was ready to move up to Will’s Creek and begin the march to the Ohio Forks.

Plan of the new town of Alexandria, with its projected new name of Belhaven which was not implemented

The 44th and 48th Regiments boarded the transports in Ireland in early January 1755 in considerable confusion. As the companies arrived at Cork harbour, they embarked with the minimum of delay onto whichever transport was ready to receive them. This was a standard procedure to avoid troops realising they were being sent abroad while they could still abscond. If a soldier deserted it was almost impossible to take action against him, even if subsequently apprehended, as the officers and NCOs who might identify him and prove his desertion were overseas. Into this hurried embarkation were introduced the drafts of soldiers from the other regiments, who also needed to be kept in the dark as to their fate.

Only once the troops were put ashore at Alexandria could the confusion be sorted out and the drafted soldiers allocated to each of the two regiments.

It is clear from the entries in the order books relating to the punishment of desertion that soldiers began to desert as soon as they landed in America, although many returned once they found there was nowhere for them to go.

Recruits in America:

Saint Clair, in his reports to Braddock, stated that it would be necessary to recruit one or more companies of ‘Carpenters’. Saint Clair realised that, in advancing through the wilderness beyond Will’s Creek which he had now experienced, the army would have to cut its way through virgin forest and build bridges over the numerous streams and areas of bog. It would be the duty of these ‘Carpenters’ to carry out this work.

Around 700 recruits were raised in Virginia prior to Braddock’s arrival. Saint Clair and Sharpe were unimpressed by the quality of these men. Saint Clair, in a letter to Braddock dated 9th February 1755, stated: “By what I saw of them, I am afraid the Officers who recruited them, have looked more to their numbers than to the goodness of the men”.

In all, the need was for some 500 men for the 44th and 48th Regiments to bring them up to a war establishment and a further 500 men for the 7 companies of Virginia Rangers and Carpenters. Once the Virginia Companies were recruited they had to be armed and trained.

British army recruiting sergeant at work: Death of General Edward Braddock on the Monongahela River on 9th July 1755 in the French and Indian War

The two regular regiments appear to have been augmented by 50% to bring them to a war establishment. Of their original soldiers at least one third were drafted in from other regiments. The 700 men forming the new Virginia companies were all recruits. A high proportion of the junior officers for the two regular regiments and all the officers for the new Virginia companies were commissioned in Virginia.

Braddock had a largely inexperienced and untrained force. It would have been prudent to have spent time training these men and permitting the units to settle down before committing them to a demanding, under-resourced and frightening form of campaign. But Braddock was determined to press on with a minimum of delay.

On 18th February 1755, Sir John Saint Clair saw 160 men at Fredericksburg. On 19th February 1755, Saint Clair saw a further detachment of 70 men at Winchester in Western Virginia.

Saint Clair travelled on to Wills Creek, where he found Governor Sharpe of Maryland with the Independent Company from South Carolina, two Independent Companies from New York (Gates’ and Rutherford’s) and a body of 80 Marylanders.

Saint Clair commented that the New York companies looked as if they had been ‘drafted out of Chelsea’ (i.e. Chelsea Pensioners or elderly). He was more impressed by the Independent Company from South Carolina and the Marylanders and commented that the remaining 150 recruits needed for the 44th and 48th might be best obtained from Maryland.

With a significant shortfall in the number of recruits, the two regiments, on arrival in America, sent recruiting parties into Virginia and Maryland, where they found a good source of recruits to be male indentured servants.

The system of ‘indentured Europeans’ has been overshadowed by the infinitely greater abuse of slavery of black Africans. The system of indenture was nevertheless objectionable. Impoverished families and individuals from Germany, Holland, Ireland and Britain obtained passage to the American colonies against an agreement to pay the ship’s captain or owner on arrival. This payment was often made by the passenger being sold into indentured service, the purchasing colonist paying the ship’s captain for the servant. Significant differences from black slavery in the colonies were that the period of indenture was finite and was followed by complete citizenship, often with a grant of money or tools, and the indentured servant retained his or her ordinary rights under the law. Many indentured servants were convicts deported to America from Britain, some of them Jacobite rebels captured after the rebellion in 1745-6. Others were simply kidnapped.

Layout of Alexandria in Virginia, before building began: Death of General Edward Braddock on the Monongahela River on 9th July 1755 in the French and Indian War

Many male indentured servants saw enlistment in the British regiments as an escape from years of bondage.

The recruiting of indentured servants caused friction with the colonists, who saw their investment in purchasing the men lost when they enlisted. Complaints went up to governor level. It is said that the 44th Regiment agreed to release enlisted indentured servants, while Dunbar of the 48th ignored the protests.

Benjamin Franklin, in his autobiography, wrote that he approached Braddock on behalf of Pennsylvanians to seek the release of indentured servants from the two British regiments and that Braddock agreed. Franklin stated that Dunbar initially agreed to release such men from his 48th Regiment, but in the event refused to do so.

It is said that none of the substantial German population of Maryland enlisted in the British regiments.

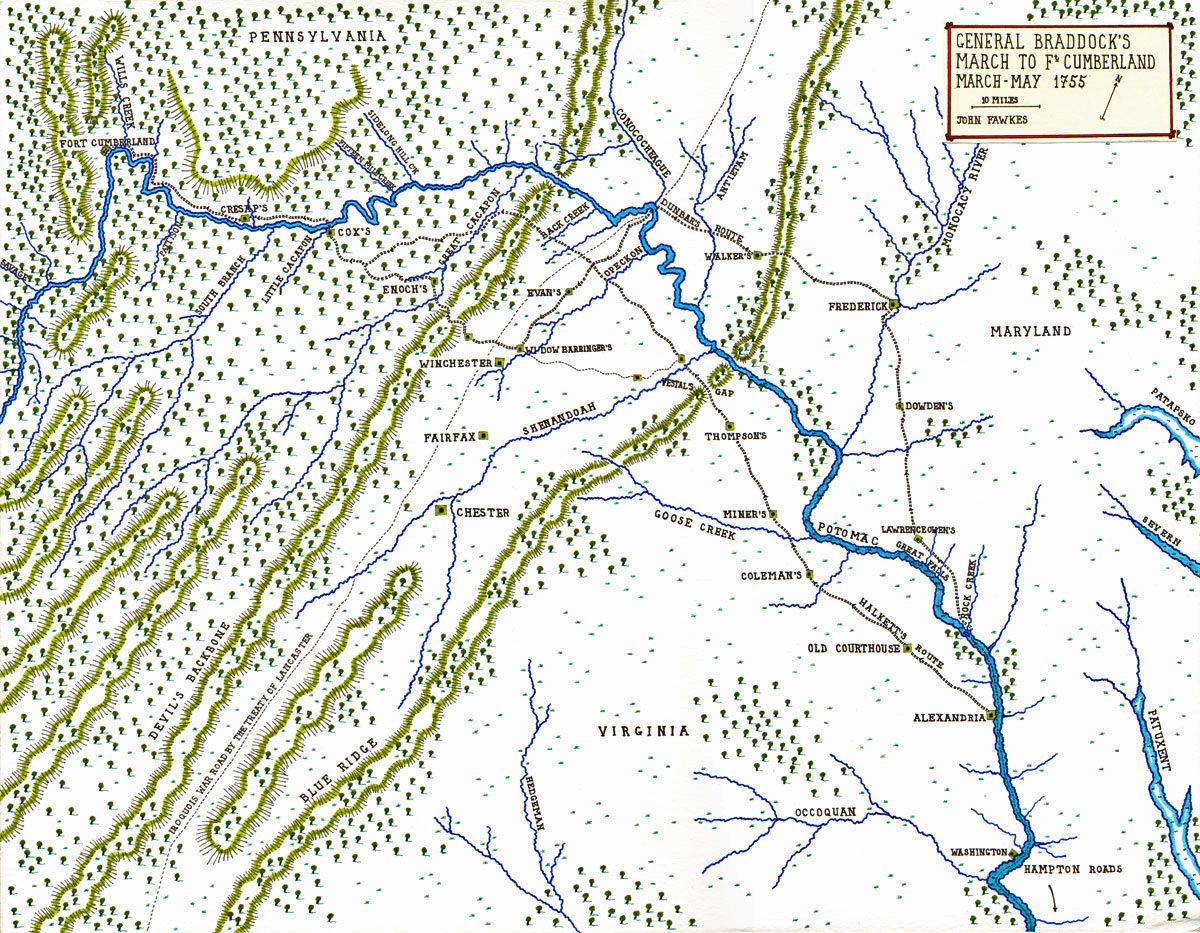

Braddock’s march to Wills’ Creek (Fort Cumberland):

On 2nd March 1755, Braddock’s aide de camp (ADC) Captain Robert Orme wrote to George Washington offering him a post as ADC to General Braddock. Washington replied on 15th March, accepting.

On 22nd March 1755, Braddock left Williamsburg for Alexandria, accompanied by Dinwiddie and Commodore Keppel, arriving on 26th March.

Braddock intended his force’s stay in Alexandria to be as short as possible, but there was a substantial delay caused while the ships were unloaded and wagons and supplies were procured. This period of delay was used to raise more recruits, attempt to train the troops and try to establish discipline, which was proving a significant problem.

Major John Carlyle of Alexandria, Commissary of Stores for General Braddock’s army

Major John Carlyle:

John Carlyle was born in Dumfriesshire in Scotland in 1720 and came to Virginia probably in the late 1730s. Through his own business abilities and his marriage into the Fairfax family, Carlyle became a member of the Virginia elite. Carlyle was one of the founding members of the Ohio Company in 1748.

With the decision taken in January 1754 to send the Virginia Regiment to the Ohio Forks to build the fort, John Carlyle was appointed Commissary of Stores for the supply of the force with food, transport, guns, small arms and ammunition. He was also responsible for paying the Virginia troops, recouping his expenditure from the Virginia Government. It was through this commission that Carlyle was appointed major.

Carlyle did not perform his duties competently, giving rise to a letter of censure from Governor Dinwiddie.

With the arrival of the Royal Troops under Braddock in early 1755, Carlyle continued in his post of Commissary for Stores.

By letter dated 10th April 1755, General Braddock appointed Carlyle ‘Storekeeper of all the Provisions, Arms Ammunition Baggage of all kinds..”

As Braddock was forced to turn to Benjamin Franklin and Pennsylvania to obtain the stores and transport he needed, again Carlyle failed to carry out his function.

Braddock and his staff were guests of Major John Carlyle during their stay in Alexandria. Major John Carlyle was probably the most prominent citizen of Alexandria, owning a large house built on a double plot in the centre of the town.

The Camp at Alexandria:

On 23rd March 1755, Captain Cholmeley’s batman (of the 48th Regiment) recorded that his regiment pitched camp (in Alexandria) and sent two recruiting parties into Maryland.

On 27th March 1755, Braddock’s issued his first orders to the army. It is apparent from these orders that Braddock had three overriding concerns: The first was the high incidence of desertion by the soldiers, although many of them returned after they discovered the inhospitable nature of the country surrounding Alexandria.

The order began with the exhortation: ‘Any soldier who shall desert tho’ he returns again will be hanged without mercy,’ (there is no record of any soldier being executed during the course of the campaign).

Braddock’s second major concern arose from the lack of a food supply in Virginia. The system in all European armies was that soldiers bought their own food with their pay. In Virginia there was little food for them to buy. In the Alexandria area the population was sparse and in any case the crop grown in Virginia was almost exclusively tobacco.

Braddock directed that the soldiers be given a daily allowance of provisions, known as the ‘King’s Allowance’. This arrangement had to be maintained throughout the campaign, as there was no time at which the soldiers could be expected to obtain provisions for themselves. The Lords of the Admiralty had had the foresight to equip the naval squadron with a substantial number of barrels of salted meat and butter for the use Braddock’s army in case it should be needed.

A daily ration of fresh or salted meat and bread with no apparent provision of vegetables or fruit carried the inevitable consequence of scurvy, which was one of the disorders that struck Braddock’s army during the march to Fort Duquesne. Several barrels of salted meat were condemned at Fort Cumberland as being too old to be fed to the troops.

Braddock’s third major concern was that the behaviour of the soldiers in camp in Alexandria was highly undisciplined. Officers and non-commissioned officers were not obeyed or treated with respect. Soldiers of all non-commissioned ranks were frequently drunk. It seems likely that there was a steady stream of injuries from careless handling of muskets, as orders were required to forbid the discharge of firearms in camp.

General Braddock’s March to Fort Cumberland through the Northern Neck of Virginia and through Maryland – March – May 1755 – Map by John Fawkes: Death of General Edward Braddock on the Monongahela River on 9th July 1755 in the French and Indian War

The ‘King’s Allowance’ was to be withheld from soldiers who were drunk, negligent or disobedient. It seems unlikely that this threat was implemented.

A striking feature of Braddock’s first order was the number of men to be on duty in the various guards across the camp. Braddock’s order provided for the main camp picquet to comprise; 1 captain, 3 lieutenants and 100 men. This was in addition to the quarter guards maintained by each of the two regiments and the artillery, of probably around 30 men for each, and the guard for the General’s quarters of 1 lieutenant and 30 men. On 28th March 1755 a provost marshal was appointed and provided with a guard of 1 sergeant, 1 corporal and 12 men. Each independent and provincial company probably maintained a picquet of around 10 men.

At any one time there would appear to have been around 250 men on picquet and guard duties. The roll of 8th June 1755 puts the number of officers and soldiers in the regiments and companies at 2,572, so that around 10% of the force encamped at Alexandria was, at any one time, on picquet duty to prevent misbehaviour by the other soldiers.

Braddock’s order directed that officers were to call the ‘Roll morning noon and night’. This step will have been to keep desertion in check and to restrain drunkenness.

Belts and swords were taken into store to prevent them being used in outbreaks of disorder (a small sword or ‘hanger’ was standard equipment for every foot soldier and often featured in incidents of violence).

Grenadier of foot, with a fifer and drummer of the Foot Guards: picture by David Morier

On 28th March 1755, a court martial was ordered to sit with Lieutenant Colonel Gage of the 44th as president and 12 other officers, with William Shirley as the judge advocate. This court martial seems to have been convened to try a soldier of the 48th, James Anderson. The charge is not given, but is likely to have been desertion, insubordination or offering violence to a superior. The sentence was 1,000 lashes with the cat of nine tails. This sentence was remitted in part, although no detail is given of the extent.

Braddock’s penultimate direction in the order of the 27th March 1755 was: ‘The nature of the country makes it impossible to provide magazines of forage. Soldiers are not to be alarmed by straggling fire from Indians on the line of march.’ It may be that Braddock felt it necessary to include this passage to attempt to allay the soldiers’ fear of the Indians. Soldiers’ gossip would focus on the rumoured war practices of the Indians; attacks with tomahawks, whooping through the trees, scalping of both live and dead enemies and the torturing of prisoners.

On 30th March 1755, one of the companies of Virginia carpenters marched out of Alexandria for Winchester, to work on improving the road from Winchester to Will’s Creek. This proved to be an impossible task in the time available.

On 31st March 1755, the artillery unloaded their guns and equipment from the ships at Alexandria with the assistance of working parties from the two regiments of foot.

On 1st April 1755, the 44th and 48th Regiments drew cartridges from the ordinance train to check that they fitted the men’s firelocks.

On Wednesday 2nd April 1755, the two regiments drew sufficient powder and shot from the artillery train to make up 24 cartridges for each soldier, the standard battle issue carried in the leather pouch hung on the shoulder belt. The Virginia Ranger Companies were attached to each of the infantry regiments: Stephen’s, Peyroney’s and Cock’s to Halkett’s 44th and Waggoner’s, Hogg’s and Polson’s to Dunbar’s 48th. Lieutenant Allen of the 44th was assigned to the Virginia companies to assist with their training. The British regiments were directed to find 3 corporals for each of the Virginia Ranger Companies. The two companies of carpenters were the concern of Sir John Saint Clair, the Deputy Quartermaster General, as their role was to make the roads at Sir John’s direction.

Colonel Halkett’s order book gave this order: “….. All officers and non-commission officers expressly forbidden to reprimand or converse with drunken soldiers but immediately confine him and deal with him when sober.”

On 3rd April 1755, Captain Robert Orme stated in his journal that the General was impatient to leave Alexandria due to the problem of the soldiers’ drunkenness in the town.

Orme recorded that Braddock went to Annapolis in Maryland on 3rd April 1755, to meet the Northern Governors; Sharpe of Maryland, Shirley of Massachusetts, Delancey of New York and Morris of Pennsylvania. The governors failed to appear, other than Governor Sharpe. Braddock ran out of patience and returned to Alexandria on 7th April 1755.

On Saturday 5th April 1755, a corporal and 6 men of the 48th Regiment marched out of Alexandria for Frederick in Maryland with the hospital stores. Each soldier carried six day’s provisions, his equipment, blanket and 24 rounds of ammunition.

Also on 5th April 1755, Braddock directed that the clothing and tents for the Virginia companies be brought ashore from the ships as soon as possible. The Virginia companies were still without uniforms, tents or weapons.

An entry in Braddock’s orders for Sunday 6th April 1755 illustrated the difficulty being experienced with drunkenness among the soldiery of all non-commissioned ranks: “a report to be made every morning to Sir Peter Halkett of the sergeants, corporals, drummers and private men who are drunk upon duty, the sergeants of the companies they belong to, to keep an exact roll of their names, Sir Peter Halkett being determined to put a stop to any more provisions being drawn for such men. Sergeants, Corporals, Drummers and private men who appear drunk in camp though they are not on duty will have their provisions stopped for one week”.

It was perhaps a novel and self-defeating form of military punishment to starve a soldier. It was almost certainly a threat that was not put into effect. The significance of the repeated orders in relation to drunkenness and misbehaviour are their revelation that Braddock’s force lacked the most basic military discipline with large numbers of soldiers of every non-commissioned rank regularly drunk and insubordinate. It is far from surprising that in the moment of crisis on 9th July 1755 this force collapsed entirely.

The next day the work began of loading wagons with equipment and supplies to be moved to Will’s Creek. An officer with a party of men marched to Rock Creek to organise the crossing of men and equipment to the north bank of the Potomac River, for the march to Frederick in Maryland by the 48th Regiment.

On Monday 7th April 1755, the Virginia companies were supplied with their uniforms and marched out for Winchester, where they would receive their weapons. The muskets had been brought from England in the ships. Presumably a decision was made that it would be better to issue them at Winchester, rather than Alexandria. No reason is given for this decision. It may be that it was to reduce the opportunity for drunken discharges, or to avoid men deserting with their weapons, or to reduce the burden on untrained men in the initial march.

On Tuesday 8th April 1755, Braddock issued directions in relation to the kit to be taken on the march to Will’s Creek: “Soldiers to leave their shoulder belts, waist belts and hanger behind and only take 1 spare shirt, 1 spare pair of stockings, 1 spare pair of shoes and 1 pair of brown gaiters.”

As the leather cartridge box hung on the shoulder belt, this being its sole purpose, it is difficult to see how the soldiers could be expected to carry the 24 cartridges issued to each man in Alexandria and carried as a matter of course throughout the marches to Will’s Creek and then to the Ohio Forks without the shoulder belt. The 24 cartridges were a bulky item and the purpose of carrying them in the leather cartridge box was to ensure they were ready to hand when it was necessary to reload the musket in battle. No mention is made of putting the cartridge boxes in store. But how were they to be carried without either shoulder or waist belt? It is to be expected that this part of the order was ignored.

On Wednesday 9th April 1755, Braddock issued a further order stating: “Officers to see that their men are provided as soon as possible with a bladder or thin leather to put between the lining and crown of their hats to guard against the heat of the sun”.

It is clear that the senior officers put some thought into reducing the uniform and equipment worn by the soldiers and into protecting them against the expected weather conditions.

On 9th April 1755, the 5 companies of Virginia Rangers and Captain Stewart’s Virginia Light Horse marched out of Alexandria for Winchester. Sir Peter Halkett’s orders stated: “As soon as they arrive at Winchester the commanding officer of companies to provide their men with arms as soon as possible, and to make application to Sir Peter Halkett for their direction. Capt Stewart is to apply immediately to Sir Peter Halkett for 34 hangers [short infantry swords] for his men which they are to take with them.”

On Friday 11th April 1755, 6 companies of the 44th Regiment marched out of Alexandria for Winchester, on the way to Will’s Creek, under Colonel Sir Peter Halkett. Lieutenant Colonel Gage commanded the 4 companies remaining in Alexandria to provide an escort for the artillery and ordinance stores when they moved.

The route prescribed for each day’s march for Halkett and his 6 companies of the 44th Regiment was:

“To the old Court House 18 miles

To Mr Colemans on Sugar Land Run where there is Indian Corn 12 miles

To Mr Miners 15 miles

To Mr Thompson the Quaker where there is 3000 wt corn 12 miles

From Mr Thompson to Winchester 23 miles”

Each man was required to carry 8 days provisions.

There was clearly some doubt as to whether there was a bridge over the Opecken River and a viable road by that route. The artillery was to be met by a detachment of the 44th Regiment and Virginia Rangers and escorted to Will’s Creek. If it turned out that the road by the Opecken bridge was usable, the artillery with its escort was to take that route direct to Will’s Creek, not via Winchester, thereby avoiding a substantial detour away from the Potomac.

Other than the artillery escort, the 44th Regiment and the 5 companies of Virginia Rangers were to remain at Winchester, until it was clear that sufficient flour had arrived at Will’s Creek from Pennsylvania and Maryland for their subsistence.

On the same day, Sir Peter Halkett issued an order indicating that there was trouble on the lines of march from disorderly soldiers, stating: “Where as complaint has been made to the general that the soldiers upon their march get drunk and abuse the people of the country and hurt their horses…. All men so offending will be most severely punished.”

In his autobiography Benjamin Franklin contrasted the oppressive conduct of Braddock’s regiments with the impeccable behaviour of the French marching through the American colonies in 1781, saying of the British troops of 1755: “In their first march too, from their landing (at Alexandria) until they got beyond the settlements (in Western Virginia and Maryland), they had plundered and stripped the inhabitants, totally ruining some poor families, besides insulting, abusing and confining the people if they remonstrated.”

On Saturday 12th April 1755, Colonel Dunbar’s 48th Regiment marched out of Alexandria, heading for Rock Creek where they would cross the Potomac River and march to Frederick in Maryland. A party of seamen; 1 officer and 30 men [including the author of ‘The Seaman’s Journal’, who as a midshipman was probably the officer] accompanied the 48th. A man was drowned during the river crossing at Rock Creek.

The route laid down for each day’s march for the 48th to Frederick was:

“Rock Creek to Owen’s Ordinary 15 miles

to Dowden’s Ordinary 15 miles

To Frederick 15 miles.”

On Sunday 13th April 1755, the artillery wagons left Alexandria for Will’s Creek, taking the Virginia route south of the Potomac River, escorted by a company of the 44th Regiment.

On the same day, the Provincial Governors arrived in Alexandria to confer with Braddock.

On Monday 14th April 1755, in the house of Captain John Carlyle in Alexandria, Braddock held his delayed conference with the Governors of the British North American colonies. Attending the conference with Braddock were Commodore Keppel, Royal Navy, Governor Shirley of Massachusetts, Lieutenant Governor Delancey of New York, Lieutenant Governor Dinwiddie of Virginia, Lieutenant Governor Sharpe of Maryland and Lieutenant Governor Morris of Pennsylvania. This was the first time some of them had met Braddock.

The conference was Braddock’s opportunity to discuss the whole campaign for North America, with the operation to be mounted against Fort Niagara, the threat in northern New York, and the assaults to be mounted against Crown Point in northern New York and Fort Beausejour in Nova Scotia and, of course, the march to Fort Duquesne.

A particularly pressing issue was the fund to finance the military operations in North America, conceived by the Duke of Cumberland and the Government in London to be established and maintained by the colonies. Braddock was disabused by the governors of any notion that sufficient money would be forthcoming from their colonial assemblies for this purpose.

Also Braddock was now realising that the attack on Fort Duquesne as the first and primary operation of the 1755 campaigning season was misconceived. The pressing threat from the French was in the north, not in the west and, in any case, if they were pushed back from Niagara, it was inevitable that the French abandon Fort Duquesne and retreat to Canada or Louisiana, depending on which route remained open to them.

The original justification given by the Duke of Cumberland for making the first attack on Fort Duquesne at the Ohio Forks had been that if operations began early in the year this was sufficiently far south for the rivers and countryside to be free of ice and snow. The delays had been such that it was now well into spring across North America and the argument no longer held good. However Braddock was bound by the most express direction from the Duke of Cumberland to make the attack on Fort Duquesne before any other action and, in any case, he was so far committed along the road to the Ohio Forks as to make any change of plan extremely difficult. It is a matter of some irony that the 48th on their march to Frederick encountered a heavy fall of snow.

The Large Parlour in the Carlyle House, where Braddock held his conference with the Northern Governors on 14th April 1755

On 15th April 1755, Dunbar’s 48th with its party of seamen reached Dowden’s Ordinary in Maryland, where they camped (an ‘Ordinary’ was a simple overnight rest house for travellers). In a few hours the weather changed from pleasant spring sunshine to a blizzard that covered the ground in snow to a depth of a foot and a half.

On 17th April 1755, the 48th Regiment reached the town of Frederick in Maryland, after crossing the Monocacy River on flats [rafts] made and operated by the seamen. The Seaman, in his journal, gave a description of Frederick: “This town has not been settled above 7 years and there are about 200 houses and 2 churches 1 English 1 Dutch. The inhabitants chiefly Dutch are industrious but imposing people. Here we got plenty of provisions and forage.”

The Grenadier Company of the 48th was sent on to Conacacheague on the Potomac, where the main route from the north crossed the river, to assist the wagons and supplies arriving from Maryland and Pennsylvania to cross the Potomac and continue on to Will’s Creek.

On Thursday 17th April 1755, the Conference with the Governors completed, Braddock left Alexandria with his ADCs Captains Orme and Morris and Secretary Shirley, the son of the Governor of Massachusetts.

On the same day, 8 wagons of gunpowder left Alexandria for Will’s Creek, with an escort of 30 men under a lieutenant from the 44th Regiment.

On Saturday 19th April 1755, Captain Cholmeley’s batman of the 48th at Frederick recorded that 4 soldiers were whipped, 1 for desertion and 3 for drunkenness, 200 lashes each.

The general hospital with a number of sick soldiers was left at Alexandria for the time being with an escort from the 48th. Charlotte Brown, author of a diary and the matron of the hospital, and her brother, a member of the medical staff, remained with the hospital.

On Monday 21st April 1755, Braddock arrived in Frederick, three days later than expected. He found the troops there in need of supplies and sent out around the countryside to purchase foodstuffs. Sir John Saint Clair, the deputy quartermaster general, arrived in Frederick soon after.

On Wednesday 23rd April 1755, Horatio Sharpe, Governor of Maryland, arrived in Frederick.

Benjamin Franklin, at this point, became an important protagonist in Braddock’s expedition. Franklin described in his autobiography that he was sent by the Pennsylvania Assembly to counter the prejudices that General Braddock was believed to have formed against Pennsylvania. Accompanied by his son, William, he met Braddock at Frederick and described dining with the general daily over a period of several days.

Franklin procured from the Pennsylvania Assembly funds to provide supplies for each of the 20 subaltern officers of the 48th Regiment. Each officer received a horse carrying sugar, tea, coffee, chocolate, biscuits, cheese, rice, raisins, ham, Madeira wine and rum. Colonel Dunbar and General Braddock were suitably appreciative.

Franklin found Braddock in some anxiety over the results of his efforts to collect wagons from Maryland and Virginia. Franklin was about to leave Frederick when the returns for the wagons obtained for the army came in.

Braddock’s officers assessed that the army needed a minimum of 150 wagons to move its supplies and baggage to Will’s Creek and then to Fort Duquesne. The returns showed that the number of wagons available was 25, some of them unserviceable. Braddock and his officers were outraged. It was even said that the expedition could not continue. They inveighed against the ministers in England for causing them to land in a colony [i.e. Virginia] that did not have the resources to support the expedition .

Franklin wrote: “I happen’d to say, I thought it was a pity they had not been landed rather in Pennsylvania, as in that Country almost every Farmer had his Wagon. The General eagerly laid hold of my Words, and said, “Then you, Sir, who are a Man of Interest there, can probably procure them for us; and I beg you will undertake it.” I ask’d what terms were to be offer’d to the Owners of the Wagons; and I was desir’d to put on Paper the Terms that appear’d to me necessary. This I did, and they were agreed to, and a Commission and Instruction accordingly prepar’d immediately. What those Terms were will appear in the Advertisement I publish’d as soon as I arriv’d at Lancaster.”

The Advertisement, dated Lancaster April 26 1753 [Franklin’s mistake: the year was 1755], stated that Braddock’s need was for 150 wagons with 4 horses to each wagon and 1,500 pack horses [again Franklin is in error in his autobiography: the need was for 250 horses]. The pay for a wagon, 4 horses and a driver was to be 15 shillings a day; for each pack horse with saddle, 2 shillings a day; and for a horse with no saddle 18 pence a day. The pay was to commence on joining at Will’s Creek, on or before 20th May, with an allowance for travelling to and from Will’s Creek. No driver was to be required to do military duty. 7 days pay in advance was to be paid on signing the contract. A mechanism was set for valuing any lost or damaged wagon with a guarantee for payment of compensation.

A ‘Connestoga’ Wagon from Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, in 1910. This form of wagon is thought to have been used in the area from the early 18th Century.

In an open letter, Franklin pointed out that this was an opportunity for the locality to earn upwards of £30,000 if the campaign lasted for 120 days. The cost of hiring wagons and pack horses was going to be £10,000 a month.

In a letter to Colonel Napier, The Duke of Cumberland’s adjutant, dated 13th June 1755, written from the camp at the Little Meadows on the march from Fort Cumberland to the Monongahela, Sir John Saint Clair stated that he believed the cost of the wagons would approach £40,000.

In the open letter, Franklin stated: “The service will be light and easy, for the army will scarce march above 12 miles per day…” In fact, during the march from Fort Cumberland to the Monongahela, Braddock’s army covered an average of 7.18 miles a day over the 20 day march; but in hard conditions due to the lack of any road and the mountainous and boggy nature of the country. On several occasions wagons had to be winched up the sides of mountains and down the far side. The service was far from ‘light and easy’.

Franklin stated in his autobiography: “I receiv’d of the General about £800 to be disbursed in Advance-money to the Wagon-owners etc: but that Sum being insufficient, I advanced upwards of £200 more, and in two Weeks, the 150 Wagons with 259 carrying horses were on their March for the Camp……..The General .. was highly satisfied in my Conduct in procuring him the Wagons..thanking me repeatedly and requesting my further Assistance in sending Provisions after him.”

The cost of the wagons threw the finances of Braddock’s expedition into chaos. Braddock sailed with a ‘float’ of £10,000 loaned to the British Government by John Hanbury to cover unforeseen expenditure. That was all Braddock had, as the main financing was intended to come from the ‘Fund’ set up and maintained by the colonies.

Pay for the two regiments was £1,000 a month. By the end of April 1755 the two regiments of foot would have been owed at least two months pay, being £4,000. The 5 companies of Virginia Rangers and 2 companies of Virginia Carpenters were not intended to be paid from Braddock’s resources as they were the obligation of the colonies. It seems unlikely that this obligation was met and that Braddock will have been forced to provide the pay for these troops.

The costs of pay and transport alone was probably at least £15,000 a month. Braddock had to fund supplies for his troops, in European conditions paid for by the soldiers out of their pay. In New York and New England the two new regiments of foot needed pay, subsistence and transport. Braddock was forced to concede the ‘King’s Allowance’ to the two new regiments in the north, when faced with an incipient mutiny.

Braddock had no specialist staff officers, only his two ADCs and a secretary, to help him keep abreast of the administration and finance.

The misrepresentation of the distance from Will’s Creek to the Ohio Forks meant that the wagons would be needed for a substantial period longer than that initially expected by Braddock.

Braddock wrote to the Duke of Cumberland’s adjutant, Colonel Robert Napier, on 19th April 1755, immediately after the Governors’ Conference at Alexandria. The letter indicates that Braddock had been led to believe that the distance from Will’s Creek to Fort Duquesne was around 15 miles. By the time he wrote this letter he understood the distance to be between 60 and 70 miles. In fact the army marched 113 miles from Will’s Creek to the point where it was attacked, 7 miles short of Fort Duquesne.

On 23rd April 1755, Captain Cholmley’s batman recorded that the 48th Regiment recruited a number of indentured servants.

George Washington wrote that he set out to join Braddock as his ADC. He described meeting the five governors at Alexandria, but clearly not Braddock, as he recorded his expectation of meeting the general at Will’s Creek. Presumably the five governors stayed on in the town after Braddock left for Frederick.

There was then considerable irritation on the part of Dinwiddie and the Virginia authorities that Maryland seemed to be making the running as Braddock’s route to Will’s Creek.

On 24th April 1755, Captain Cholmley’s batman (48th at Frederick) recorded: “Enlisted several indentured servants kidnapped in England and sold to the Planters. Several prisoners punished for being drunk. One for not learning his exercise (weapons drill).”

On Friday 25th April 1755, Captain Cholmley’s batman (48th at Frederick) recorded: “Drew Indian corn for 6 days. Told marching on Tuesday. Whipped several men for drinking.”

On the same day, the Seaman (with the 48th at Frederick) recorded: “received orders to be ready to march on Tuesday next. Arrived here 80 recruits and some ordnance stores.”

On Sunday 27th April 1755, the artillery marched out of Alexandria with their 12 pounder and 6 pounder guns, escorted by Captain Hobson’s company of the 44th Regiment and accompanied by the 44th Regiment’s staff, the remaining companies of the regiment still in the town and those members of the Virginia companies who had been in hospital but had recovered. 10 days provisions were carried. The order directing the march ended by declaring that any man “that shall be found any way in liquor …. when the company marches will be severely punished”. The route taken was through Virginia. A party of pioneers marched in advance to ensure the road was in a state to receive the wagons and guns of the artillery.

That night this force reached the Old Court House where they encamped. The orders were: “1 sergeant 1 corporal and 12 men to mount guard immediately upon the wagons. The pioneers to march tomorrow at 4am. The horses to be harnessed by 6am and the general to beat at 7am when the party is to parade and march directly.”

On 29th April 1755, the 48th Regiment with its party of sailors marched out of Frederick in Maryland for Will’s Creek. The route directed was:

“29th April road to Conocacheague 17 miles

30th April to Conocacheague 18 miles

1st May to John Evans 16 miles

2nd May rest

3rd May to the widow Baringer 18 miles

4th May to George Poll’s 9 miles

5th May to Henry Enoch’s 15 miles

6th May rest

7th May to Cox’s at the mouth of the little Cacaphon 12 miles

8th May to Col Cresap’s 8 miles

9th May to Will’s Creek 16 miles

129 miles.

Take 3 days provisions; at Conocacheague more and at Widow Baringer’s 5 days, at Col Cresap’s 1 or more days, and at all these places oats or Indian corn for the horses but no hay.

At Conocacheague troops cross the Potomac in a float. When troops have marched 14 miles from John Evans they are to make the new road to their right which leads to the Opeckon Bridge.

When the troops have marched 14 miles from George Polle’s they come to the great Cacaphon pass the river on a float and turn right.

If the water in the Cacaphon is high the troops must encamp opposite to Cox’s.

At the mouth of the little Cacaphon the Potomac is to be crossed in a float. 4 miles beyond they cross Town Creek if the float not finished canvas will be provided.

If the bridges not finished over Will’s Creek and Evans Creek, wagons will be ordered to carry the men across. Proper to get 2 days provisions if not arrive at Col Cresap’s until 10th.”

On 29th April 1755, the Seaman recorded: “We began our march [from Frederick] at 6 but found much difficulty in loading our baggage so that we left several things behind us, part the men’s hammocks. We arrived at 3 at one Walker’s 18 miles from Frederick and encamped there on good ground. This day we passed the South Ridge or Shanandoah Mountains, very easy in the ascent. We saw plenty of hares, deer and partridges. This place is wanting of all refreshments.”

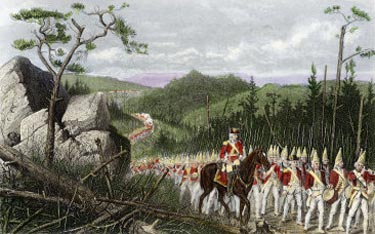

British troops on the march to Will’s Creek

Still in Alexandria with the General Hospital, Charlotte Brown, to her delight, on this day received a letter from her children left in England. It was dated 4th February.

Lieutenant Colonel Gage with the artillery and his 4 companies of the 44th Regiment camped that night at Miner’s in Virginia.

On 30th April 1755, the 48th Regiment with the party of sailors reached Conococheague Creek, the crossing point on the Potomac River for the wagons coming south from Pennsylvania and Maryland. The junction of the Conococheague with the Potomac was where the path to the south used by the Indians was confirmed by the Treaty of Lancaster.

On 1st May 1755, the 48th Regiment with the sailors crossed the Potomac to the south bank and marched to the Widow Evans’. The Sailor commented “The roads now begin to be very indifferent.”

Orme’s journal recorded that Braddock went to Winchester in Western Virginia, expecting to meet Indians prepared to serve with him. There were none, so he went on to Fort Cumberland. The timing of Braddock’s arrival at Will’s Creek would indicate that he stayed several days in Winchester.

Lieutenant Colonel Gage with the artillery and his 4 companies of the 44th Regiment marched to Mr Thompson’s on their route through Virginia, where they camped. The regiment’s order stated: “Sergeant and 12 men to mount the baggage guard and sentries to be posted on the wagon horses. General at 3am at which time the horses are to be put to the wagons. Wagoners to be told if any horses not ready or any missing they will be punished.”

On Friday 2nd May 1755, the Sailor stated: “As is customary in the army to halt a day after 3 days march, we halted today to rest the Army and sent the horses to grass.”

Lieutenant Colonel Gage with the artillery and his 4 companies of the 44th Regiment marched on to the Shenendoah River, where they camped.

On 3rd May 1755, Captain Cholmley’s batman (48th Regiment) stated: “marched to Widow Billinger’s [Barringer’s] 19 miles received 2 day’s provisions. Drummed a woman out of camp.” This camp was a few miles from Winchester in Western Virginia.

The route taken by the 48th crossed over the 44th’s route, so that the 48th was now to the south of the 44th, who were marching along the Potomac River bank.

In Alexandria, Charlotte Brown was visited in her lodgings by Mrs Sarah Carlyle. As Mrs Brown did not have chairs for them to sit on, Mrs Carlyle sent to her house for three chairs.

Lieutenant Colonel Gage with the artillery and his 4 companies of the 44th Regiment camped at Dick’s Plantation. There was continuing difficulty with the wagon horses. Orders stated: “1 corporal and 9 men to guard on the artillery and baggage. 1 sergeant to take the number of horses as they are put into the pasture. 1 tent to be pitched in the front of the artillery and another in the rear of the baggage. General at 4am and march immediately.”

On 4th May 1755, the Seaman [with the 48th Regiment] recorded: “Marched at 5am in our way to one Potts – 9 miles from the Widow’s- where we arrived at 10am. The road this day very bad: we got some wild turkeys here: in the night it came to blow hard at North-West.”

In Alexandria, Charlotte Browne recorded: “This day was obliged to quit our grand parlour, the man of the house being at a loss for a room for the soldiers to drink cider and dance jigs in.”

This entry is perhaps revealing in suggesting that the inhabitants of Virginia (and Maryland?) did very well out of the soldiers drinking habits.

On Monday 5th May 1755, the Seaman [with the 48th Regiment] recorded: “Marched at 5am in our way to one Henry Enock’s, a place called the forks of Cape Capon being 16 miles from Potts where we arrived at 2pm. The road this day over prodigious mountains and between the same we crossed over a run of water 20 times in 3 miles distance. After going 15 miles we came to a river called Kahapetin, where our men ferried the Army over and got to our ground where we found a company of Peter Halkett’s [44th Regiment] encamped.”

Lieutenant Colonel Gage with the artillery and his 4 companies of the 44th Regiment marched to Widow Littler’s Mills.

In Alexandria, Charlotte Browne recorded: “Removed into our first floor. It consisted of a bed chamber and dining room not over large. The furniture was 3 chairs, a table, a case to hold liquor and a tea chest.”

George Washington wrote to William Fairfax from Winchester, saying: “I overtook the General at Frederick Town in Maryland and thence we proceeded to this place, where we shall remain till the arrival of the 2nd Division of the Train (which we hear left Alexandria on Tuesday last); after that we shall continue our march to Wills Creek; from whence it is imagined we shall not stir till the latter end of this month, for want of wagons and other conveniences to transport our baggage over the mountains.”

On 6th May 1755, the Seaman [with the 48th Regiment] recorded: “We halted this day to refresh the army. The officers for passing away the time made horse races and agreed that no horse should run over 11 hands and to carry 14 stone.”

Captain Cholmley’s batman [48th Regiment] recorded: “halted received 5 day’s provisions but no forage for horses. Nothing to be bought. Would have starved without King’s Allowance.”

In Alexandria, Charlotte Browne recorded: “This unhappy day 2 years deprived me of my dear husband and ever since to this day my life has been one continual scene of anxiety and care.”

George Washington wrote from Winchester to Lord Fairfax: “The general sets out tomorrow and proceeds directly to Wills Creek… A very fatiguing ride and long round brought me to the general (the day I parted with you) at Frederick Town, a small village 15 miles below the Blue Ridge in Maryland from thence we proceeded to this place where we have halted since Saturday last and shall depart for Wills Creek tomorrow.

I find there is no probability of marching the army from Wills Creek till the latter end of this month or the first of next so that you may imagine time will hang heavy upon my hands. I meet with a familiar complaisance in this family, especially from the general, who I hope to please without difficulty, for I may say it can scarce be done with as he uses, and requires less ceremony than you can well conceive.”

By ‘family’ Washington means General Braddock’s staff.

On Wednesday 7th May 1755, the Seaman [with the 48th Regiment] recorded: “We marched at 5am in our way to Cox’s, 12 miles from Enock’s. This morning was very cold but by 10 it was prodigiously hot. We crossed another run of water 19 times in 2 miles and got to our ground at 2 and encamped close to the Potomack.”

Halkett’s Order Book [the 4 companies of the 44th accompanying the artillery] directed: “THE WOOD THREE MILES SHORT OF MRS JENNINGS: 1 sergeant and 12 men for guard on artillery and baggage from the front to the rear. General at 6am and march immediately after.”

On Thursday 8th May 1755, Captain Cholmley’s batman [48th Regiment] recorded: “Marched to Colonel Cresap’s and crossed Potomac 9 miles.”

Colonel Cresap’s was on the Maryland bank of the Potomac River, some 16 miles to the east of Will’s Creek, and was near the point where the various parties crossed back to the north bank of the Potomac from the Virginia side, for the final march to Fort Cumberland at Will’s Creek.

The Seaman [with the 48th Regiment] recorded: “We began to ferry the Army over the river into Maryland which was completed by 10 and then we marched on our way to one Jackson’s 8 miles from Cox’s. At noon it rained very hard and continued so till 2pm when we got to our ground and encamped on the banks of the Potomack. A fine situation with a good deal of clear ground about it. Here lives one Colonel Cressop, a rattle snake colonel and a vile rascal: calls himself a Frontier man as he thinks he is situated nearest the Ohio of any inhabitants of the country and is one of the Ohio Company. For his defence has built a log fort round his house. This place is the track of the Indians and Warriors when they go to war either to the Northward or Southward. There we got plenty of provisions etc and at 6 the General arrived here with his attendants and company of light horse for his guard and lay at Cressop’s. As this was a wet day the general ordered the army to halt tomorrow.”

On Saturday 10th May 1755, the Seaman [marching with Colonel Dunbar’s 48th Regiment] described their arrival at Will’s Creek (Fort Cumberland), and their encounter with the North American Indians assembled at the camp: “Marched at 5 on our way to Will’s Creek, 16 miles from Cressops, the road this day very pleasant by the water side. At 12 the general passed by, the drums beating the Grenadier March. At 1 we halted and formed a circle when Col Dunbar told the army that as there were a number of Indians at Will’s Creek our friends, it was the general’s positive orders that they do not molest them or have anything to say to them, directly or indirectly for fear of affronting them. We marched again and heard 17 guns fired at the fort to salute the general. At 2 we arrived at Will’s Creek and encamped to the westward side of the fort on a hill and found here 6 companies of Sir Peter Halkett’s regt, 9 companies of Virginians and a Maryland company.…. ”

General Braddock’s army was now at Fort Cumberland and beginning the final preparations for the advance to Fort Duquesne on the Ohio River.

The previous section on Braddock’s defeat on the Monongahela in 1755 is Part 5: Braddock’s regiments, Halkett’s 44th and Dunbar’s 48th, and his departure for Virginia.

The next section on Braddock’s defeat on the Monongahela in 1755 is Part 7: Braddock’s army at Fort Cumberland in Maryland in May 1755.

To the French and Indian War index