Frederick’s heavy defeat at the hands of the Russians on 12th August 1759

The fighting in the Kuh-Ground at the Battle of Kunersdorf on 12th August 1759 in the Seven Years War: picture by Kotzbue

The previous battle in the Seven Years War is the Battle of Hochkirch

The next battle in the Seven Years War is the Battle of Liegnitz

Battle: Kunersdorf

Date of the Battle of Kunersdorf: 12th August 1759.

Place of the Battle of Kunersdorf: In Neumark, east of the Oder.

War: The Seven Years War.

Contestants at the Battle of Kunersdorf: Prussians against a Russian Army and a strong Austrian contingent.

Generals at the Battle of Kunersdorf: King Frederick II of Prussia, known as Frederick the Great, commanding the Prussian Army against General Saltykov commanding the Russian Army. General Loudon commanded the Austrian contingent.

Size of the Armies in the Battle of Kunersdorf:

Prussians: 36,900 infantry, 13,000 cavalry and 140 heavy guns.

Russians: 41,000 and 200 guns. Austrians: 18,523 and 48 guns.

Winner of the Battle of Kunersdorf: The Russians and Austrians.

Uniforms and equipment at the Battle of Kunersdorf: The Prussian infantry and artillery wore a dark blue coat turned back at the lapels, cuffs and skirts, with britches and black thigh length gaiters. Each soldier carried on a cross belt an ammunition pouch, bayonet and ‘hanger’ or small sword. Headgear for the line companies was the tricorne hat, with a flattened front corner, bound with white lace. Grenadiers wore the distinctive mitre cap with a brass plate at the front. Fusilier infantry regiments and artillery wore a smaller version of the grenadier cap.

The infantry carried a musket as the main weapon. This single shot firearm could be loaded and fired by a well trained soldier around 3 to 4 times a minute. As an early improvement Frederick introduced the iron ramrod and then the reversible ramrod (the soldier did not have to worry whether he had the ramrod the right way round) which increased the rate of fire of his infantry, the old wooden ramrod being liable to break in the stress of battle.

The Prussian infantry regiment was based on the cantonment with soldiers joining their local regiment. In peacetime soldiers were released for key agricultural times, sowing and harvesting. In the autumn, reviews were conducted of all regiments to check they were up to the required standard. Each year regiments were selected to undergo review at Potsdam under the eye of the King. Officers whose soldiers’ performance was considered by Frederick to be substandard were subject to a public tongue lashing and in extreme cases dismissal on the spot.The efficiency of the Prussian regiments at drill enabled them to move about the battlefield with a speed and manoeuvrability that no other European Army could equal. The Battle of Rossbach is a striking example of this facility.

During the peace between the sets of wars Frederick devised and practised his ‘oblique’ formation in attack. The technique was to deliver an assault on the flank of an enemy army. The Prussian infantry battalions would advance to the attack ‘in echelon’, or each battalion, after the leading battalion, setting off 50 paces after its predecessor. The Battle of Leuthen was the only battle in which Frederick was able to deliver a complete ‘oblique’ attack and did so with devastating success.

Heavy cavalry of the period comprised cuirassiers and dragoons. The Prussian cuirassiers wore a white coat, steel cuirass, white britches and thigh boots. Prussian Dragoons wore a light blue coat. The headgear was a tricorne hat. Weapons were a heavy cavalry sword and single shot flintlock carbine.

The light cavalry arm was provided by the Prussian Hussar regiments. The true hussars were Hungarians in the Austrian service. The hussars of other armies were given the same dress as the original hussars and required to perform a similar light cavalry role of reconnaissance and harassing the enemy’s outposts and supply columns.

Following the Battle of Mollwitz and in particular after the First Silesian War the Prussian Hussars were re-organised and re-trained to provide an efficient scouting and light cavalry service. Frederick found in Colonel von Zieten the ideal officer to implement the improvements in the hussar regiments. The Prussian Hussars wore the traditional hussar dress of tunic, britches, dolman (slung jacket), busby (fur hat) with bag, sabretache (leather wallet on straps hanging from the belt) and curved sword.

Unlike the original Hungarian Hussars of the time who were considered to be little more than indisciplined freebooters the Prussian Hussars were well able to take a position in the cavalry line and perform valuable service in battle, as at the Battle of Hohenfriedburg and on other occasions.

The Austrian infantry wore white coats with lapels, cuffs and skirts turned back showing the regimental lining colour. Headgear was the tricorne hat for line infantry and bearskin cap for grenadiers. The infantry weapons were musket, bayonet and hanger small sword. Heavy cavalry wore white coats and hats as for the infantry and were armed with a heavy sword and carbine. The Austrian army contained a large number of irregular units such as the Pandours from the Balkans who wore their ethnic dress without uniformity. Hungarian Hussars provided the light cavalry arm. These Hussars were dressed as described for the Prussian Hussars, were considered to be little more than bandits but were highly effective in all the roles required of light cavalry.

The artillery of each army was equipped with a range of muzzle loading guns.

Prussian Leibregiment zu Pferde No 3: picture by Adolph Menzel as part of his series of pictures ‘Die Armee Friedrichs des Grossen

in ihrer Uniformierung’

In most respects the Russian army mirrored that of the western powers in structure, uniforms and weapons. The Russian infantry wore green coats. The cavalry comprised cuirassier, dragoon and hussar regiments. The Russians relied upon a large force of Cossack irregular cavalry. The Cossacks pillaged far and wide and were of limited use to the Russian commanders, often being too busy looting to spend much time on the pursuits of scouting and harassing enemy troops.

Frederick implemented significant improvements to the Prussian Army between the two Silesian wars. The eleven years of peace before the Seven Years War enabled Frederick to bring the various arms of the Prussian service to a further high pitch of efficiency. Each year the regiments were subjected to a training cycle that culminated in reviews at Potsdam under the King’s exacting eye. Autumn manoeuvres were held in Silesia, the area where much of the expected warfare would be conducted (see the benefit of these manoeuvres at the Battle of Leuthen).

The Prussian infantry was a tested and established asset and required little improvement. Most of the innovation was targeted at the cavalry, artillery and technical arms.

One unfortunate development from the Silesian Wars was that Frederick formed the view that his infantry could win their battles simply by the steadiness of their advance. The Seven Years War began with the Prussian infantry doctrine being to advance with muskets at the shoulder and not to pause to fire on the enemy. The Battle of Prague showed this doctrine to be badly misguided and it was abandoned after causing the Prussians substantial casualties.

The Prussian infantry was soon trained to advance making brief halts to fire and reload, enabling it to deliver successive volleys as it marched up to the opposing army, a technique used to devastating effect at the Battle of Rossbach.

During the course of the Seven Years War Frederick extensively re-organised the artillery. New equipment was introduced, the guns standardised and the artillery formations overhauled. Frederick introduced horse artillery that could move around the battlefield.

Frederick brought the Prussian cavalry to a level of effectiveness unrivalled by any other European Army of any period. The basic requirement was a high standard of horsemanship in every soldier. A trooper was required to ride his horse every day, an exacting obligation in peacetime. Contrast this with the practice of the British regiments of horse and dragoons of the time, in which as a measure of economy the horses had their shoes struck off and were put out to grass unridden for the whole of the summer (see Viscount Molesworth’s standing orders for his dragoon regiment).

Every year Frederick exercised the cavalry during the autumn manoeuvres. Frederick required the cuirassier and dragoon regiments to form line at the gallop and deliver a charge, with the troopers so close that they rode knee behind knee with the horses touching. Frederick developed the capability of the cavalry year by year. Finally he required his mounted regiments to be able to deliver three such charges one after the other at full gallop.

Austrian cavalry attacking Prussian infantry at the end of the Battle of Kunersdorf on 12th August 1759

The effect of this exacting training was graphically illustrated by the performance of the Prussian cavalry force led by General von Seydlitz against the Russians at the Battle of Zorndorf on 25th August 1758. Seydlitz’s squadrons crossed the Zabern-Grun stream, climbed the steep far bank and moved through an area of scrub, before forming two lines of hundreds of troopers at the gallop, so close together that the horses were touching, and delivering a devastating charge at full gallop against unshaken Russian infantry, who were overwhelmed. Against cavalry of this quality it mattered little whether the infantry was in line or square.

This extraordinary ability contrasted with most other European cavalry regiments which would form for the charge at the halt and then attack in a loose formation which would be lost in the course of the charge, ending with the horses blown and all cohesion gone. If the infantry under attack seemed unduly aggressive, the attacking cavalry would be liable to swerve around them or pull up.

It was Frederick’s order that any Prussian cavalry commander receiving a charge at the halt would be tried by court-martial. Commanders had the discretion to attack if they considered that a favourable opportunity existed, without waiting for orders.

The Battle of Rossbach is another good example of the quality of the Prussian heavy cavalry and its ability to deliver battle winning charges through remaining under the tight control of its commander.

Background to the Battle of Kunersdorf:

Following the Austrian defeat of Frederick’s Prussian army at the Battle of Hochkirch on 14th October 1758 the balance of the year was a success for the Prussians. The Austrians were manoeuvred away from the Saxon capital Dresden, which was held by the Prussians, and the Silesian town of Neisse was recovered for Frederick.

1759 started with Frederick waiting to see what action would be taken against him by his principal adversaries, the Austrians, Russians and the German Reichsarmée. At the beginning of July 1759 Frederick received the information he needed. Daun was moving with an army of 75,000 Austrians towards Lusatia and General Saltykov was assembling a Russian army of 60,000 at Posen in Western Poland with the intention of crossing the Oder and invading Brandenburg, the heart of Prussia.

General Dohna commanded the Prussian army of 28,000 men east of the Oder River with the role of holding back the Russians. Dohna failed completely to prevent Saltykov’s advance towards the Oder.

At the end of July 1759 Frederick sent Lieutenant General Kurt Heinrich von Wedel to replace Dohna and attack the Russians.

Saltykov managed to march around Wedel and positioned his army across Wedel’s lines of communications. Wedel attacked the Russians at Paltzig on 23rd July 1759. In a disastrous battle the Prussians were thrown back with casualties of around 8,000 men. Saltykov continued his advance to the Oder and prepared to take the city of Frankfurt.

Account of the Battle of Kunersdorf:

Following receipt of the news of Wedel’s defeat at the hands of the Russians Frederick immediately put his army in motion from Sagan in Central Silesia towards the Oder. Frederick’s aim was to prevent Saltykov and his Russians from crossing the Oder River and invading Brandenburg. Frederick left his brother Prince Henry with an army of 44,000 Prussians to hold Silesia against the Austrians.

Slightly in advance of Frederick’s departure Daun despatched 2 corps of Austrians under Generals Haddik (17,500 men) and Loudon (25,000 men) to join Saltykov.

Frederick hearing of the potential reinforcement of the Russians attempted to overtake the 2 Austrian corps. He intercepted Haddik’s baggage train but Haddik had already given up the attempt to reach the Oder before Frederick. The deviation from the Prussian’s most direct route gave Loudon the opportunity to join Saltykov before Frederick came up with the Russians. Loudon crossed the Oder and joined Saltykov on 5th August 1759.

Prussian Husaren-Regiment von Zieten No 2: picture by Adolph Menzel as part of his series

of pictures ‘Die Armee Friedrichs des

Grossen in ihrer Uniformierung’

On his arrival on the west bank of the Oder Frederick formed a camp at Mulrose to the South of Frankfurt-an-Oder and went through the operation of incorporating Wedel’s defeated troops into his own army. In addition Frederick was joined by a force of Prussians under Lieutenant General Fink which had been covering Berlin.

Frederick determined to carry out against Saltykov the same plan he had implemented against his predecessor, General Fermor, at the Battle of Zorndorf: that is to cross the Oder well downstream of the Russian positions and return by the right or eastern bank of the river.

Frederick’s army marched down the Oder to a point at Göritz, just short of Custrin, and there established a bridgehead followed by the necessary bridges. The army crossed the Oder during the night of 10th August 1759 and began the march south, arriving at Bishofsee just short of the Russian positions around Kunersdorf before dawn of 11th August 1759.

Prussian Husaren-Regiment von Belling No 8: picture by Adolph Menzel as part of his series of pictures ‘Die Armee Friedrichs des

Grossen in ihrer Uniformierung’

With dawn Frederick observed the terrain and the Russian positions in order to devise his plan of attack. A local squire and a forestry official were questioned by the King but seemed incapable of providing useful information about the area.

Frederick conducted a personal reconnaissance from the Trettiner Spitz-berg and saw that the Russians had prepared positions along a low ridge or series of hillocks stretching off towards the right diagonally from a point to the front of where he stood. Frederick spent the 11th August 1759 preparing the plans for his attack. General Fink would remain on the north side of the Russian positions while Frederick took the main body around the Russian right and attacked their positions in the rear.

One of the main purposes of this plan was to cause the Russians to leave their prepared positions and face in the opposite direction. What Frederick did not realise was that Saltykov had expected the Prussian attack to come from the South so that his entrenchments faced in that direction. With the approach of the Prussians from the North the Russians had faced about. Frederick’s outflanking march would take the Prussians around to the Russian front and not their rear.

The weather was baking hot and the Prussian troops were exhausted by their long approach march. The terrain was dry and sandy. Movement was difficult and the soldiers suffered from heat and thirst.

As Frederick’s main army emerged into the area to the south of the Russians the King saw that there was a row of large ponds stretching from the Russian lines at right angles which limited the area in which he could manoeuvre to that immediately in front of the eastern section of the Russian position. Instead of attacking along the Russian front the attack would have to be confined to the Russian flank. The forced change of plan took place at short notice and the Prussian columns were required to change direction to focus on the Russian flanking positions.

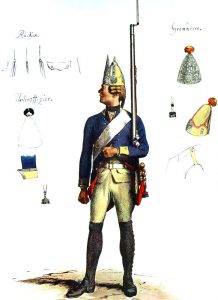

Prussian Füsilier-Regiment Prinz Heinrich No 35: picture by Adolph Menzel as part of his series of pictures ‘Die Armee Friedrichs des

Grossen in ihrer Uniformierung’

Sixty Prussian guns were established in 3 batteries on the Walk-Berge, Kloster-Berg and the Kleiner-Spitzberg. At around 11.30am these guns opened a heavy barrage on the end Russian position on the Muhl-Berge.

The garrison of the redoubt on the Muhl-Berge comprised 5 large regiments of the Russian Observation Corps with 40 guns. The Prussian barrage overwhelmed the Russian garrison so that when the Prussian infantry launched their assault on the Muhl-Berge the Russians were quickly overwhelmed.

The capture of the Muhl-Berge was a devastating blow for the Russians. A quarter of the Russian line was lost with some 80 guns taken or destroyed and heavy casualties amongst their infantry.

Senior Prussian generals, Fink and probably Seydlitz, pressed Frederick to abandon any further attack as the Russians would inevitably be forced to retreat. The ferocious heat made the battle a terrible ordeal for all the troops involved. But Frederick was looking for a decisive defeat of the Russians. He insisted that the attack must continue.

The Prussian heavy batteries were hauled over to the positions in the Muhl-Berge for the next phase of the battle. Once in position they opened fire on the Russians.

Prussian Füsilier-Regiment von Kursell No 37 (the regiment lost 16 officers and 992 men in the battle) : picture by Adolph Menzel as part

of his series of pictures ‘Die Armee Friedrichs des Grossen in ihrer Uniformierung’

Following the barrage the Prussian infantry began their attack across the Kuh-Grund that lay between the Muhl-Berge and the next Russian redoubt in the line. The Kuh-Grund was a narrow sandy valley. It was heavy going for the Prussian infantry and the Russians brought substantial forces and numbers of guns to this point, knowing that the Prussian attack was now on a narrow front.

Frederick brought up more infantry and sent them into the attack. Fink assaulted the northern side of the Russian redoubt. The fighting ranged along the southern and northern sides of the Russian position.

The Prussian cavalry were committed to the battle in small packets to support the infantry. The Austrian and Russian cavalry counter-attacked and were in turn driven back as more Prussian cavalry under Seydlitz joined the fight.

Seydlitz was injured and left the battle. Major-General Puttkamer was killed leading his regiment of White Hussars into the assault following an earlier attack by Lieutenant General the Prince of Württemburg.

In the late afternoon with the other senior Prussian cavalry commanders casualties Lieutenant General Platen led the Prussian cavalry into an attack on the Russian position in the Grosser Spitzberg. The regiment of Schorlemer Dragoons was wiped out by Russian gunfire. As the remaining regiments attempted to form up they were charged by Lieutenant General Loudon leading Austrian and Russian cavalry. The Prussian cavalry was decimated in the attack.

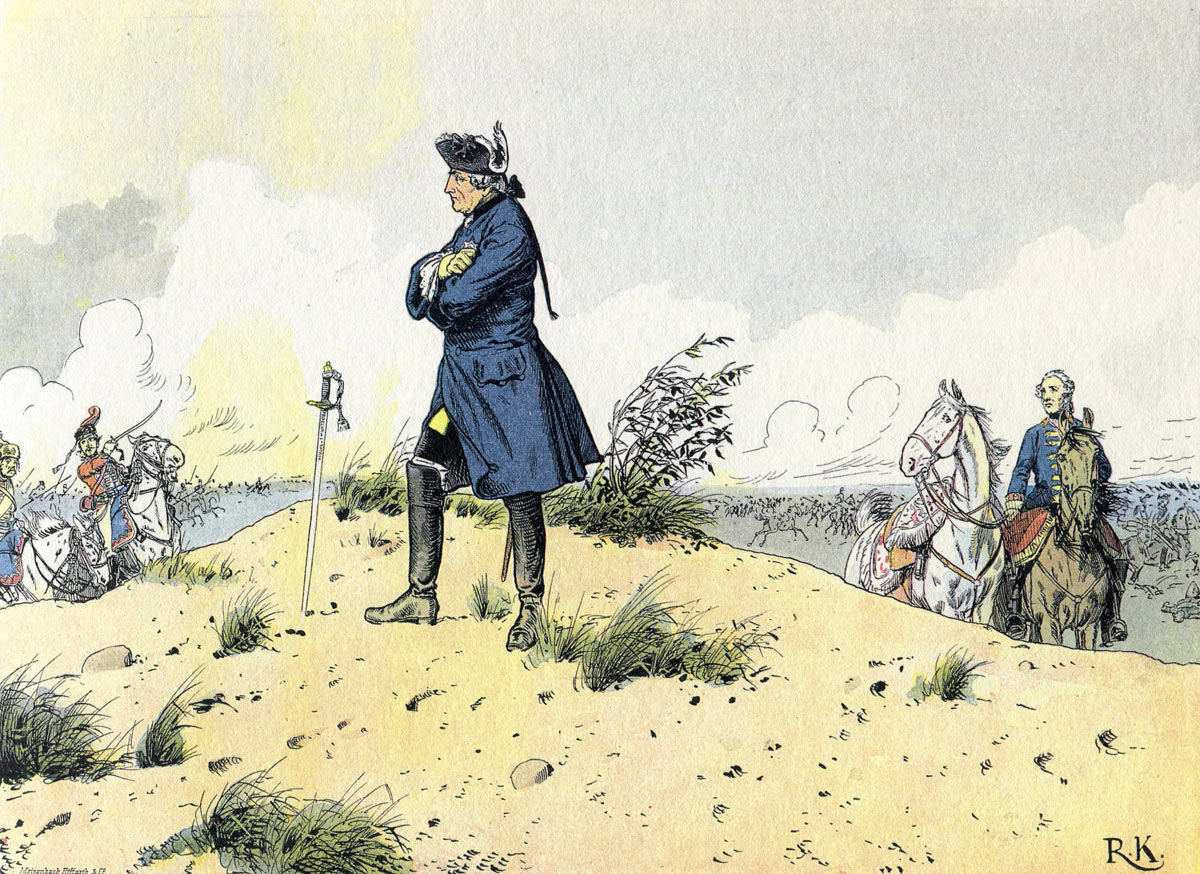

Frederick the Great at the Battle of Kunersdorf 12th August 1759 in the Seven Years War: picture by Richard Knötel

By now the Prussian infantry and cavalry, unable to make any significant impression on the Russian positions, were collapsing in flight. Frederick had to be rescued from a party of Cossacks by his escort of Zieten Hussars commanded by Captain Prittwitz.

The Prussian army fled North and crossed the Oder at Göritz. Frederick was prostrated both emotionally and physically and abdicated command to Fink. He expected the Prussian state to collapse following this dreadful defeat.

Casualties at the Battle of Kunersdorf: Prussian losses: 19,100 men killed, wounded and captured and 172 guns lost. Russian losses: 13,500 killed, wounded and captured. Austrian losses: 2,000 men killed, wounded and captured.

Prussian Dragoner-Regiment von Schorlemer No 6: picture by Adolph Menzel as part of his

series of pictures ‘Die Armee Friedrichs des Grossen in ihrer Uniformierung’

Aftermath to the Battle of Kunersdorf:

Immediately following the battle the Prussian army crossed the Hühner-Fliess where it spent the night. A rain-less thunder storm caused the night to be illuminated by lightning. Frederick crossed to the west bank of the Oder River but then returned to be with his defeated army as his officers attempted to restore some semblance of order and discipline to the defeated and disintegrated regiments. On 14th August 1759 Frederick led the army across the Oder River to the West Bank.

One of the most striking features of Frederick the Great’s military genius was his resilience and ability to recover from the disastrous defeats the Prussian army suffered. Kunersdorf was particularly bitter for Frederick in that he knew that it was substantially his fault. Frederick had badly underestimated the fighting qualities of the Russian army in spite of his previous experience of the tenacity of the Russian soldier at the Battle of Zorndorf on 25th August 1758. Frederick had failed to heed the advice of his generals to end the battle with the successful capture of the Mühl-Berge. After a period of deep depression during which he wrote to Count Schmettau permitting him to surrender Dresden, which he duly did, Frederick recovered and resumed the field.

Frederick was rescued by the failure of the Austrian and Russian generals fully to exploit the victory of Kunersdorf. Saltykov crossed the Oder River into Brandenburg, threatening Berlin, and Daun marched north from Saxony with a large Austrian army. But when Daun’s lines of communication were threatened by Prince Henry with a Prussian army Daun retreated to Saxony. Saltykov marched to the South East re-crossed the Oder River and retreated into Poland.

Prussian Füsilier-Regiment von Rohr No 47: picture by Adolph Menzel as part of his series

of pictures ‘Die Armee Friedrichs des Grossen in ihrer Uniformierung’

Anecdotes from the Battle of Kunersdorf:

- The Prussian officer Frederick consulted on the local topography before the battle was Major Linden. Linden had been in the habit of hunting in the Kunersdorf area before the war. Linden turned out to be unable to describe the lay of the land to Frederick in any useful form. A senior local forestry official was also consulted but was equally unhelpful. It seems that the official was overwhelmed to find himself addressed by his king.

- The weather on the day of the battle was hot and dry. The Prussians found the heat very difficult. The dryness had the effect of making the going over the sandy ground slow and hard, particularly in the Kuh-Grund dip which had to be crossed to reach the main Russian position.

- In the course of Fink’s infantry attacks from the North East a unit that particularly distinguished itself was the battalion of the Regiment Hauss (No. 55) commanded by Major Ewald von Kleist. Kleist was known in the Prussian army as a poet. Kleist led his men against the Russian emplacements and suffered wound after wound, finally falling from his horse, shot down by the battery he was attacking. Kleist died the next day.

- Attempting to rally his infantry Frederick seized a colour from the Regiment of Prince Henry (No 35) and called out “If you are brave soldiers, follow me.” None did. Frederick attempted to make a stand on the Muhl-Berge with the regiments of Lestwitz (No 31) and the Diericke Fusiliers (No 49) but both regiments were cut down by the Russian artillery fire.

References for the Battle of Kunersdorf:

- Frederick the Great by Thomas Carlyle

- Frederick the Great by Christopher Duffy

- The Army of Frederick the Great by Christopher Duffy

- The Army of Maria Theresa by Christopher Duffy

- Russia’s Military Way to the West by Christopher Duffy

The previous battle in the Seven Years War is the Battle of Hochkirch

The next battle in the Seven Years War is the Battle of Liegnitz