The first battle of Frederick the Great’s long struggle to conquer Silesia from the Austro-Hungarian Empire; a battle won by the incomparable Prussian infantry

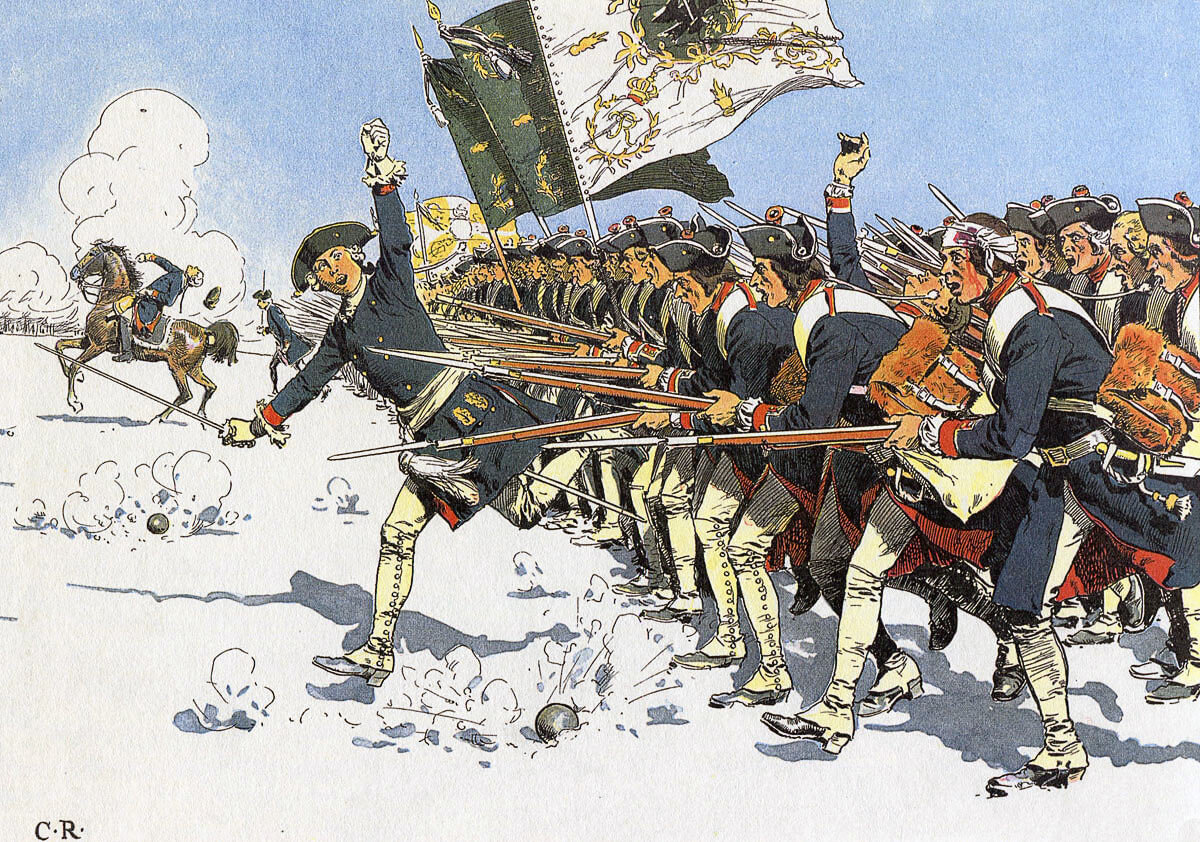

Prussian infantry assault at the Battle of Mollwitz on 10th April 1741 in the First Silesian War: picture by Carl Röchling

The previous battle in the British Battles series is the Battle of Culloden

The next battle in the First Silesian War is the Battle of Chotusitz

To the First Silesian War index

Battle: Mollwitz

Date of the Battle of Mollwitz: 10th April 1741.

King Frederick II of Prussia known as ‘Frederick the Great’: Battle of Mollwitz fought on 10th April 1745 in the First Silesian War

Place of the Battle of Mollwitz: At the village of Mollwitz on the approaches to Neisse, a Silesian town situated on the River Oder.

War: The First Silesian War.

Contestants at the Battle of Mollwitz: Prussians against an Imperial Austrian Army comprising the various nationalities that made up the Austrian Army (Austrians, Hungarians, Bohemians, Silesians, Croats, Italians and Moravians).

Generals at the Battle of Mollwitz: King Frederick II of Prussia and Field Marshall Von Schwerin against Field Marshall Neipperg, the Austrian Commander.

Size of the Armies at the Battle of Mollwitz:21,600 Prussians (16,800 infantry and 4,000 cavalry) against 19,000 Austrians (10,000 infantry and 8,000 cavalry).

Winner of the Battle of Mollwitz: The Prussians.

Prussian Infantry Regiment von Pannwitz No 10: Battle of Mollwitz fought on 10th April 1745 in the First Silesian War: picture by Adolph Menzel

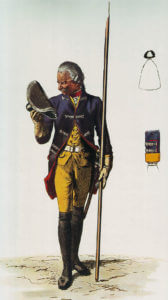

Uniforms and equipment at the Battle of Mollwitz: The Prussian infantry and artillery wore a dark blue coat turned back at the lapels, cuffs and skirts, britches and white thigh length gaiters. From cross belts hung an ammunition pouch, bayonet and ‘hanger’ or small sword. Headgear for the line companies was the tricorne hat with the receding front corner bound with white lace. Grenadiers wore the distinctive mitre cap with the brass plate at the front. Fusilier Infantry Regiments and gunners wore the smaller version of the grenadier cap.

The infantry carried the musket as their main weapon. The single shot musket could be loaded and fired by a well trained soldier between 3 and 4 times a minute. During the course of his wars Frederick introduced the iron ramrod and then the reversible ramrod which increased the efficiency of his infantry, the wooden ramrod being liable to break in the stress of battle.

The Prussian infantry regiment was based on the cantonment, with soldier joining their local regiment. Soldiers were released for key agricultural times such as sewing and harvesting. In the autumn reviews were conducted of all regiments to check that each regiment was up to the required standard. Each year certain regiments were selected to conduct the review at Potsdam under the eye of the King. Officers whose soldiers were considered by Frederick not to be of a sufficient standard were subjected to a public tongue lashing and in extreme cases dismissed on the spot.

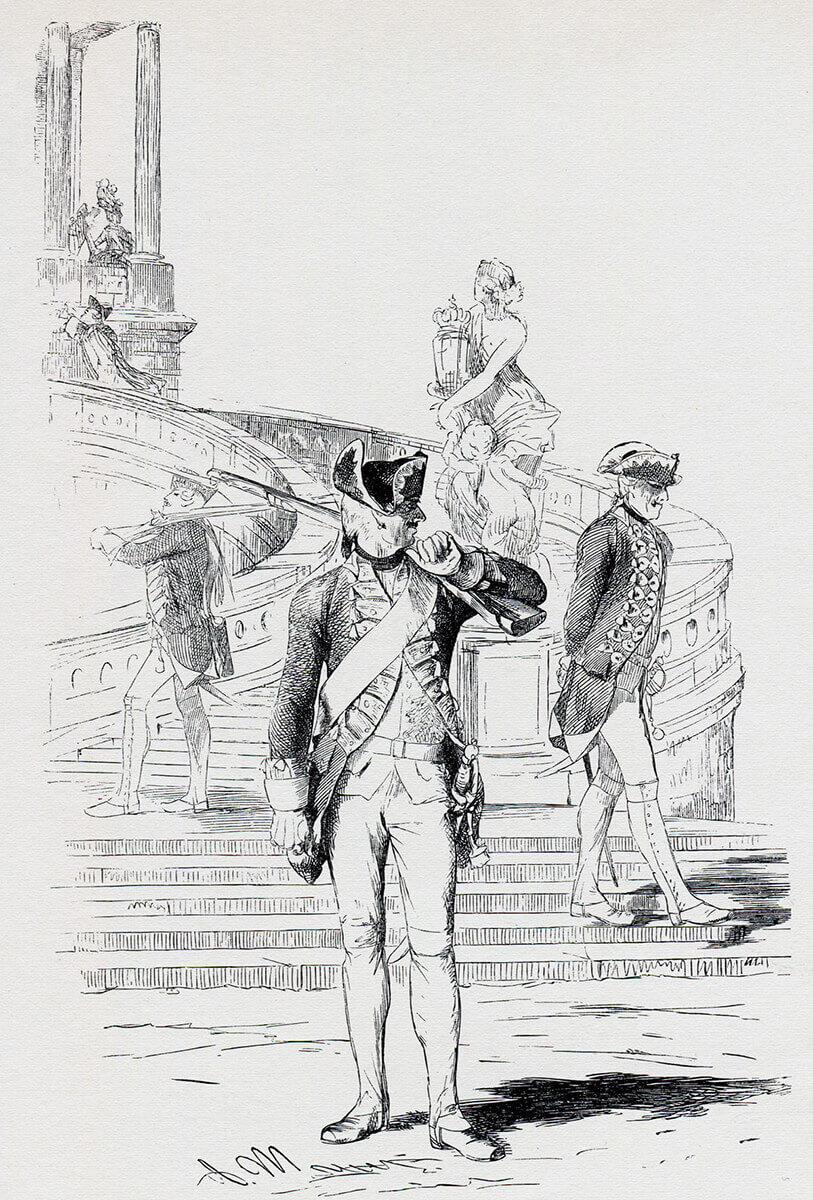

Prussian First Guards Battalion: Battle of Mollwitz fought on 10th April 1745 in the First Silesian War: picture by Adolph Menzel

The efficiency of the Prussian regiments at drill enabled them to move around the battlefield with a speed and manoeuvrability that no other European Army could equal.

Prussian Leib-Karabinier-Regiment No 11: Battle of Mollwitz fought on 10th April 1745 in the First Silesian War: picture by Adolph Menzel

Heavy cavalry of the period comprised cuirassiers, whose troopers wore steel breastplates, and dragoons. The main form of light cavalry were the regiments of hussars. The Austrian hussars were Hungarian and the genuine article while the hussars of other armies were given the same dress as Hungarian hussars and expected to perform to similar standards.

The Prussian cuirassiers wore a white coat, steel cuirass, white britches and thigh boots. The headgear was the tricorne hat. Dragoons wore a light blue coat. Weapons were a heavy cavalry sword and single shot flintlock carbine.

The light cavalry arm was provided by the Prussian Hussar regiments. Frederick found the Prussian Hussars as inadequate for their role as the heavy cavalry regiments. Following Mollwitz and in particular after the First Silesian War the hussars were re-organised and re-trained to provide a first class scouting and light cavalry service. Frederick found in Colonel von Zieten the ideal officer to implement the improvements in the hussar regiments. The Prussian Hussars wore the traditional hussar dress worn by the original Hungarian Hussars of tunic, britches, dolman (slung jacket), busby (fur hat) with bag, sabretache (leather wallet on straps) and curved sword.

Austrian Infantry : Grenadiers of 2 Austrian regiments and the Hungarian regiment of Ujvary: Battle of Mollwitz fought on 10th April 1745 in the First Silesian War: picture by David Morier

The Austrian infantry wore white coats with lapels, cuffs and skirts turned back showing the regimental lining colour. Headgear was the tricorne hat for line infantry and bearskin cap for grenadiers. The infantry weapons were musket, bayonet and hanger small sword. Heavy cavalry wore white coats and hats as for the infantry and were armed with a heavy sword and carbine. The Austrian army contained a large number of irregular units such as the Pandours from the Balkans who wore their ethnic dress without uniformity. Hungarian Hussars provided the light cavalry arm. These Hussars were dressed as described for the Prussian Hussars, were considered to be little more than bandits but were highly effective in all the roles required of light cavalry.

Austrian 1st Regiment of Cuirassiers ‘Hohenzollern-Hechingen’: Battle of Mollwitz fought on 10th April 1745 in the First Silesian War: picture by David Morier

The artillery of each army was equipped with a range of muzzle loading guns. The Prussian Artillery was considerably more efficient at manoeuvring on the battle field. In the changes implemented by Frederick after the First Silesian War horse artillery was introduced to support the Prussian cavalry.

The Battle of Mollwitz Background

The Prussian Army and State of the middle of the 18th Century owed its strength to the father of Frederick the Great, King Frederick William, the ‘Soldier King’. The Kingdom of Prussia comprised a number of areas scattered across Northern Germany from Minden and the tiny provinces of Jules and Berg in the West to the more compact provinces of Pomerania and East Prussia on the Baltic coast in the East. The capital of Prussia lay in the City of Berlin in the heartland of Brandenburg. During his reign Frederick William established an efficient civil state with the primary duty of supporting a large and well organised army, the bedrock of which was the Prussian Infantry. The noble families of Prussia were required to commit their sons to the army’s officer corps. Unlike the military nobility in other European states the Prussian Officer Corps was expected to devote its energies to learning its fighting trade. Regiments were reviewed on an annual basis by the King and woe betide the officers of any regiment that fell below the required standard of drill and performance.

Prussian Grenadiers: Battle of Mollwitz fought on 10th April 1745 in the First Silesian War: picture by David Morier

The Prussian Army established the technique of battlefield drill in the era of the musket. Prussian Infantry regiments could be trusted to move around the battlefield in order and at speed in a way that no other army could. Frederick the Great, while undoubtedly owing a great deal to the work his father had carried out on the army and state, brought his own unique talents to bear in improving the infantry and forging formidable assets out of the arms his father had neglected; principally the cavalry and the artillery, after the dismal performance of the Prussian cavalry at Mollwitz.

Prussian Dragoner-Regiment No 1: Battle of Mollwitz fought on 10th April 1745 in the First Silesian War: picture by Adolph Menzel

Frederick William had a reverence for the established order in Europe, holding the Emperor of Austria in particular awe. He would not have dreamt of launching Prussia on the extraordinary series of wars Frederick the Great began in 1741 by invading the Austrian province of Silesia.

Frederick William died on 31st May 1740 and Frederick II took the throne of the Kingdom of Prussia. On 20th October 1740 the Emperor Charles VI of Austria died leaving the imperial throne to his daughter Maria Theresa. Frederick resolved to seize the Austrian province of Silesia for Prussia.

Prosperous and partly Protestant, Silesia lay on the southern Prussian border along the banks of the river Oder. With its population of 1.5 million Frederick saw Silesia as a significant addition to the Prussian state with its 2.2 million inhabitants. But Frederick would have to fight 3 wars over 22 years with the Austro-Hungarian Empire for his prize.

Frederick invaded Silesia on 16th December 1740 after months of preparation. He crossed the border south of the Prussian town of Crossen and marched south down the west bank of the River Oder. On 3rd January 1741 Breslau, the capital of Silesia, opened its gates to Frederick.

Frederick II King of Prussia enters Breslau, the capital city of Silesia after the Battle of Mollwitz fought on 10th April 1745 in the First Silesian War: picture by Richard Knötel

By March 1741 the Prussian army occupied the countryside of Silesia to its southern border, where the Prussian troops were dispersed for the remainder of the winter. Key towns remained held for Austria, notably Neisse. On 9th March 1741 Prince Leopold of Anhalt-Dessau, son of the ‘Old Dessauer’ stormed Glogau.

Spurred on by the Empress Maria Theresa, the Austrian army showed its determination to re-conquer Silesia. In April 1741 Marshal Neipperg entered Silesia, speedily passing the Prussian army and heading to relieve the garrison at Neisse on the Oder. Frederick concentrated his army and followed Neipperg. The Prussians came up with the Austrian army and attacked it at Mollwitz, a village immediately to the South of Neisse.

Other than a brief attachment to the Imperial Army on the Rhine in 1734 Frederick was devoid of practical military experience, other than commanding an infantry regiment in peacetime. Mollwitz was the first of Frederick’s battles. He left its conduct to Field Marshall Schwerin. Never again would Frederick abdicate command in this way.

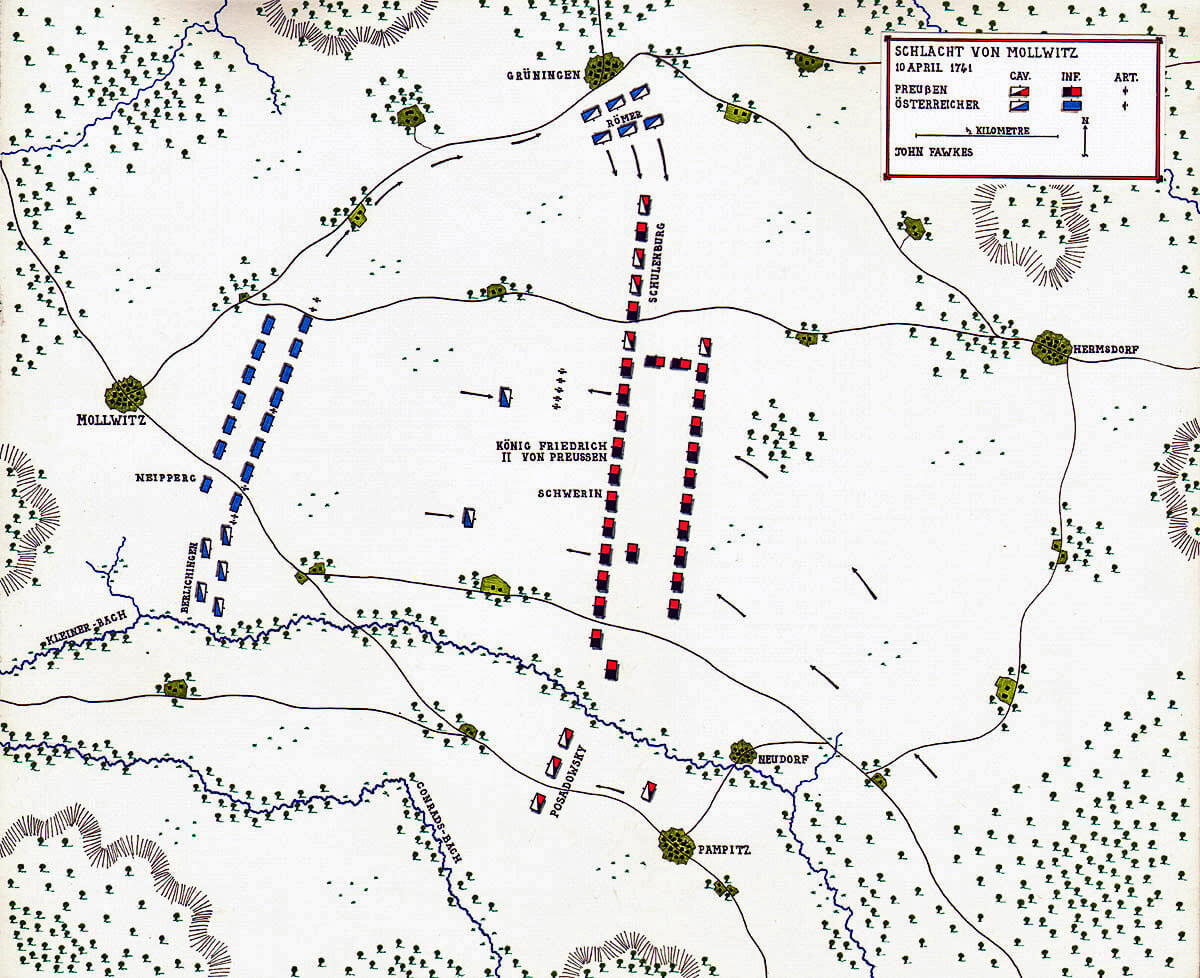

Map of the Battle of Mollwitz fought on 10th April 1745 in the First Silesian War: map by John Fawkes

The Battle of Mollwitz : The Account

There were heavy falls of snow on 9th April 1741, the day before the battle. The Prussian army advanced in five columns, expecting to surprise the Austrian army in the village of Mollwitz. The army halted to deploy into line for the attack on a line between the villages of Grϋningen on the right and Pampitz on its left. Frederick later analysed his errors at this point as making a frontal attack and deploying into line too far short of the Austrian positions, so that the advance in line, cumbersome and slow, was made over a considerable distance . An additional error was that there was insufficient room for the 2 lines of Prussian infantry with its flanking cavalry forces.

The Prussian artillery advanced in front of the line and repeatedly unlimbered to bombard the Austrian positions. The gun shots threw up clouds of powdery snow reducing visibility.

Prussian Infantry Regiment von Selchow No 12: Battle of Mollwitz fought on 10th April 1745 in the First Silesian War: picture by Adolph Menzel

The Austrian army lay around the village of Mollwitz. Initially surprised by the appearance of the Prussian Army, the Austrians were brought to arms and prepared for the battle. The Austrians had no experience of fighting the Prussian Army and its officers expected to have an easy victory.

The Austrian commander launched a powerful cavalry attack with the regiments on his left flank. The attack was led by General Römer and fell on the Prussian right flank held by the cavalry regiments commanded by General Schulenberg. The Prussian cavalry were at this time below the standards of the experienced and battle hardened Austrian Cuirassiers and Dragoons headed by General Römer.

The Prussian deployment on the right flank was seriously defective in that cavalry and infantry regiments were intermingled preventing a co-ordinated deployment of the mounted regiments. The Prussian cavalry regiments received the Austrian charge at the halt, a serious breach of the golden rules of mounted action, and were overthrown. Frederick led a cuirassier regiment into the fray in an attempt to stay the collapse of the Prussian cavalry, only to be born away in the rout.

Prussian Infantry Regiment von Meyerinck No 26 fifer (the regiment lost 25 officers and 667 men in the battle): Battle of Mollwitz fought on 10th April 1745 in the First Silesian War: picture by Adolph Menzel

Frederick, advised by Field Marshall Schwerin that he had lost the battle and that his army was about to be destroyed, paused only to change mounts and rode away from the battlefield with his personal entourage. He rode hard for the town of Oppeln where he narrowly escaped capture by Hungarian hussars. Moving on to the town of Löwen, Frederick received a message from Field Marshall Schwerin informing him that the battle had been won.

Frederick returned to find that the Prussian infantry had held firm, driven off the Austrian cavalry and advanced to occupy Mollwitz. Neipperg had withdrawn from the field and retreated back across the border, leaving the Prussians the victors.

Casualties at the Battle of Mollwitz: The Prussians suffered 4,850 dead and wounded. The Austrians suffered 4,250 dead and wounded.

Aftermath to the Battle of Mollwitz: Frederick was too relieved at winning to take advantage of his victory. He was dismayed at the inadequacy of the Prussian cavalry and spent the following months in camp at Mollwitz re-organising the Prussian force and working on his theories of warfare. No further major operations took place in Silesia until August 1741.

Mollwitz Grey at grass in later years: Battle of Mollwitz fought on 10th April 1745 in the First Silesian War: picture by George Stubbs

Anecdotes from the Battle of Mollwitz:

- Frederick is said not have forgiven Field Marshall Schwerin for urging him to leave the battlefield.

- The horse Frederick rode from the battlefield to Oppeln and whose stamina and speed enabled Frederick to escape from the pursuing hussars was given the sobriquet of the ‘Mollwitz Grey’ (Mollwitzer Schimmel) and retired from further service. The horse was put out to grass at Potsdam and was occasionally ridden by the king.

- A captured Austrian officer described the advance of the Prussian infantry at the closing stages of the battle as ‘like an advancing wall.’ Frederick was unduly influenced by the moral effect of the Prussian advance and in several subsequent battles is said to have failed to use the infantry’s firepower to the extent that he might have done.

Frederick the Great greeting the Mollwitz Grey in later life: Battle of Mollwitz fought on 10th April 1745 in the First Silesian War: picture by Richard Knötel

- One of the striking features of Frederick’s military career is the extent to which he strived to improve his army and his own understanding of warfare. Every battle and campaign brought about a flurry of thoughts, directives and papers for his generals and for himself. Re-organisation and re-training of every arm of the Prussian service was on-going. There appeared to be no sacred cows.

References for the Battle of Mollwitz:

Frederick the Great by Thomas Carlyle

Frederick the Great by Christopher Duffy

The Army of Frederick the Great by Christopher Duffy

The Army of Maria Theresa by Christopher Duffy

The previous battle in the British Battles series is the Battle of Culloden

The next battle in the First Silesian War is the Battle of Chotusitz

To the First Silesian War index